Abstract

The WHIM syndrome is a rare immunodeficiency disorder characterized by warts, hypogammaglobulinemia, infections, and myelokathexis. Dominant heterozygous mutations of the gene encoding CXCR4, a G-protein–coupled receptor with a unique ligand, CXCL12, have been associated with this pathology. We studied patients belonging to 3 different pedigrees. Two siblings inherited a CXCR4 mutation encoding a novel C-terminally truncated receptor. Two unrelated patients were found to bear a wild-type CXCR4 open reading frame. Circulating lymphocytes and neutrophils from all patients displayed similar functional alterations of CXCR4-mediated responses featured by a marked enhancement of G-protein–dependent responses. This phenomenon relies on the refractoriness of CXCR4 to be both desensitized and internalized in response to CXCL12. Therefore, the aberrant dysfunction of the CXCR4-mediated signaling constitutes a common biologic trait of WHIM syndromes with different causative genetic anomalies. Responses to other chemokines, namely CCL4, CCL5, and CCL21, were preserved, suggesting that, in clinical forms associated with a wild-type CXCR4 open reading frame, the genetic anomaly might target an effector with some degree of selectivity for the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis. We propose that the sustained CXCR4 activity in patient cells accounts for the immune-hematologic clinical manifestations and the profusion of warts characteristic of the WHIM syndrome.

Introduction

The CXC chemokine stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1/CXCL12)1,2 is the sole natural ligand for CXCR4,3,4 a broadly expressed G-protein–coupled receptor (GPCR).5 The unique, non-promiscuous interaction between CXCL12 and CXCR4 is critically involved in the organogenesis of a number of phylogenetically distant animal species.6-11 In addition, B-cell lymphopoiesis and bone marrow (BM) myelopoiesis are regulated by the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis during embryogenesis.12-14 In postnatal life, the CXCL12/CXCR4 couple controls the BM homing of CD34+ cells and lymphocyte trafficking.15-18 Besides the regulation of homeostatic processes, CXCR4 has been implicated in the development of infectious3,19 and inflammatory diseases as well as tumor metastasis.20-23 Recently, inherited heterozygous autosomal dominant mutations of the CXCR4 gene, which result in the truncation of the carboxyl-terminus (C-tail) of the receptor, were found to be associated with the WHIM syndrome.24 This rare immunodeficiency disease is characterized by disseminated human papilloma-virus (HPV)–induced warts, hypogammaglobulinemia, recurrent bacterial infections, and myelokathexis, a form of neutropenia associated with abnormal retention of mature neutrophils in the BM.25-27 Patients with WHIM also exhibit a marked T-cell lymphopenia. The disorder is clinically and genetically heterogeneous,28 since hypogammaglobulinemia and verrucosis were absent in some cases,29 and individuals with isolated myelokathexis were found to be wild type for the CXCR4 gene.24 However, the altered mechanism accounting for the pathogenesis of the WHIM syndrome not associated to CXCR4 mutations remains unknown. Here, we provide original evidence that individuals with incomplete or full clinical forms of the WHIM syndrome, and carrying either a mutated or a wild-type CXCR4 open reading frame (ORF), share biologic anomalies targeting CXCR4-dependent signaling.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patients and sample processing

Patients P1 and P2 (pedigree I, 41 and 38 years old, respectively), P3 (pedigree II, 43 years old), and patient P4 (pedigree III, 17 years old) (Figure 1A) displayed clinical features of the WHIM syndrome. Disseminated, cutaneous warts caused by common serotypes of HPV were observed in the 4 patients, with anal and genital condylomata in patients P1, P2, and P3. Sporadic, genital infections by herpes viruses were observed in patients P1 and P3. Bacterial infections of the respiratory tract were frequent in all patients and caused pulmonary atelectasia in patient P4, requiring surgical removal of the affected lobe. Patients P1 and P2 showed the typical pattern of isolated myelokathexis in BM biopsies. A similar pattern was found in patients P3 and P4. Indeed, histologic analysis of BM proved in both patients the presence of dysgranulopoiesis with increased amount of mature neutrophils exhibiting hypersegmented nucleus characteristic of myelokathexis. Like in patients P1 and P2, no dyslymphopoiesis or dyshematopoiesis were observed in patients P3 and P4. All the patients showed a marked leukopenia (< 2 × 109/L) affecting both B- and T-cell subpopulations, in particular the CD4+ T-cell subset. In patient P3, lymphocyte counting maintained below 0.4 × 109/L, while in patient P4 it was regularly below 0.2 × 109/L. In patient P3, CD14+ monocytes were not detected. Profound neutropenia (< 0.4 × 109/L) was observed in patients P1 and P2 and was less pronounced in patients P3 and P4: 1 × 109/L or slightly below for patient P4, while in patient P3 it oscillated between 1.1 × 109 and 1.6 × 109/L. Global hypogammaglobulinemia was observed in patients P1 (< 3 g/L,), P2 (< 6 g/L; normal levels of immunoglobulin G1 [IgG1]), and P4 (< 6 g/L; normal levels of IgG2 and IgG3). For patient P3, γ-globulin values were in the low limits of the normal range. Patient P1 displayed a marked anemia (hemoglobin, < 80 g/L) and thrombocytopenia (< 50 × 109/L). Mild normocytic, normochromic, nonregenerative anemia, and thrombocytopenia were observed in patients P2, P3, and P4. T-cell responses to vaccine antigens were preserved in patients P1, P2, and P3 and moderately affected in patient P4. Healthy blood donor volunteers were matched for age and sex and used as control subjects. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) were isolated from heparin-treated blood samples using Ficoll-Paque Plus (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden) density gradient centrifugation as previously described.30 The local ethics committee approved this study, and all subjects gave informed consent for this investigation.

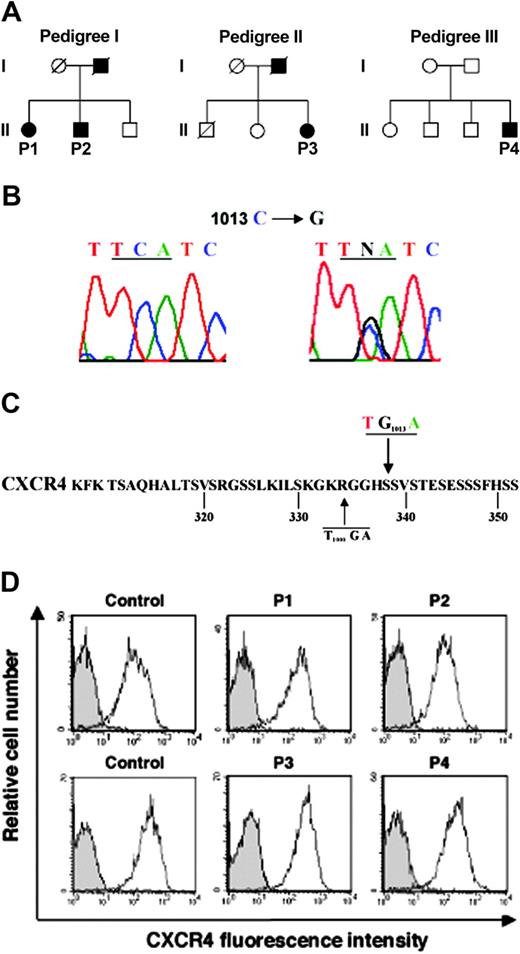

Analysis of the CXCR4 ORF in patients with WHIM. (A) Patients P1 and P2 (pedigree I) inherited the disease-associated haplotype from their father. Patient P3 (pedigree II) inherited the disease-associated haplotype from her father. Patient P4 (pedigree III) is the fourth child of healthy, nonconsanguineous parents and might constitute a sporadic case. (B) Electrophoregram of the CXCR4 cDNA sequence from patient P1 (right panel) encompassing a C1013 → G substitution. The same mutation was detected in patient P2. Left panel shows for patient P3 the equivalent CXCR4 cDNA wild-type sequence. (C) In the amino acid sequence of the CXCR4 C-tail, the mutation recovered in patients P1 and P2 introduces a nonsense codon (underlined) in place of Ser-338. The previously reported WHIM-associated CXCR41000 is shown.24 (D) Cell surface expression of CXCR4 in CD3+-gated PBMCs from the 4 patients and 2 independent healthy donors was determined by flow cytometry using the PE-conjugated 12G5 (empty histograms) or isotype control (gray histograms) monoclonal antibody (mAb).

Analysis of the CXCR4 ORF in patients with WHIM. (A) Patients P1 and P2 (pedigree I) inherited the disease-associated haplotype from their father. Patient P3 (pedigree II) inherited the disease-associated haplotype from her father. Patient P4 (pedigree III) is the fourth child of healthy, nonconsanguineous parents and might constitute a sporadic case. (B) Electrophoregram of the CXCR4 cDNA sequence from patient P1 (right panel) encompassing a C1013 → G substitution. The same mutation was detected in patient P2. Left panel shows for patient P3 the equivalent CXCR4 cDNA wild-type sequence. (C) In the amino acid sequence of the CXCR4 C-tail, the mutation recovered in patients P1 and P2 introduces a nonsense codon (underlined) in place of Ser-338. The previously reported WHIM-associated CXCR41000 is shown.24 (D) Cell surface expression of CXCR4 in CD3+-gated PBMCs from the 4 patients and 2 independent healthy donors was determined by flow cytometry using the PE-conjugated 12G5 (empty histograms) or isotype control (gray histograms) monoclonal antibody (mAb).

CXCR4 mutation identification

Total messenger RNAs extracted (RNeasy kit; QIAGEN Sciences, Courtabeuf, France) from freshly patient-isolated PBMCs were reverse transcribed (Superscript; BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) by extension of oligo(dT) priming using a “template-switch” (TS) primer 5′-AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGTAC[T]20VN-3′.31 Subsequent amplification of oligo-dT primed cDNA was performed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR; Advantage II pol; BD Biosciences Clontech) (40 cycles at 95°C for 30 seconds and 68°C for 3 minutes) using specific CXCR4 forward 5′-AGTAGCCACCGCATCTGGAGAAC-3′ and reverse 5′-ACAAAAATCCAACAAGCAATAAAAACTG-3′ primers. Additionally, a 3′–step-out rapid amplification of CXCR4 cDNA ends31 was performed using specific CXCR4 forward primer and TS-PCR reverse primers. Double-strand sequencing of amplification products was performed to, at least, a 4-fold redundancy by primer walking.

CXCR4 constructs and expression

The nonsense mutations TG1000A and TG1013A (Figure 1C) were introduced in the CXCR4 coding region by PCR and confirmed by sequence analysis. The CXCR4wt, CXCR41000, and CXCR41013 cDNAs were cloned into the pTRIP vector and were expressed following a lentiviral-based strategy32 in PBMCs from healthy individuals activated (> 90% CD25+ blasted T cells) with phytohemagglutinin (PHA; 1 μg/mL) and 20 ng/mL interleukin-2 (IL-2; PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) or in the CXCR4-negative A0.01 T-cell (from Dr HT He, Centre d'Immunologie de Luminy, Marseille, France) and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell lines (ATCC, Rockville, MD). For some experiments, the T7-GFP-CXCR4wt cDNA (kindly provided by Dr G. Gaibelet, IPBS/CNRS, Toulouse, France), cloned into the pcDNA3 plasmid, was used. We controlled that the functioning of the resulting CXCR4wt chimera was wild-type-like. These CXCR4wt chimeras were expressed following the calcium phosphate-DNA coprecipitation method in CXCR4wt- or CXCR41013-expressing CHO cells or simultaneously with CXCR4wt or CXCR41013 using the amaxa Nucleofector technology (Cologne, Germany) in PBMCs from healthy individuals. Experiments were performed 36 hours after transfection and 15 hours after nucleoporation.

Functional evaluation of chemokine receptors

Flow cytometry analysis were carried out on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, Rungis, France) using the following anti–human monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) (from Becton Dickinson unless specified): CD3 (clone SK7), CD8 (clone B9.11 and clone 53-6.7; Immunotech, Beckman-Coulter, Marseille, France), CD25 (clone M-A251), CD4 (clone RPA-T4), CXCR4 (clone 12G5), CCR5 (clone 2D7), and the rat anti–human CCR7 (clone 3D12). The binding of the mouse anti–T7-Tag mAb (Novagen; EMD Biosciences, Darmstadt, Germany) was revealed using the secondary phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated goat anti–mouse F(ab′)2 Ab (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark).

Chemokine receptor internalization was studied as previously described.33 Briefly, cells were incubated at 37°C unless specified for 45 minutes with 200 nM CXCL12 (from Dr F. Baleux, Unité de Chimie Organique, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France) or 6Ckine/CCL21 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), or for 75 minutes with 200 nM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO). After 1 wash in acidic glycine buffer (pH = 2.7), levels of receptor cell surface expression were determined using the corresponding PE-conjugated mAbs alone in A0.01 T-cell and CHO cell lines, or in combination with fluorescent mAbs specific for T-cell antigens (CD3, CD8, and CD4) in PBMCs. Background fluorescence was evaluated using the corresponding PE-conjugated, immunoglobulin-isotype control mAb. No receptor internalization was found when cells were incubated at 4°C in the presence of ligand. Receptor expression in stimulated cells was calculated as follows: (receptor geometric mean fluorescence intensity [MFI] of treated cells/receptor geometric MFI of unstimulated cells) × 100; 100% correspond to receptor expression at the surface of cells incubated in medium alone.

Chemotaxis was performed using a Transwell assay23 upon induction with chemokines. Briefly, 3 × 105 cells in 150 μL RPMI medium supplemented with 20 mM HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid) and 1% human AB serum were added to the upper chamber of a 6.5-mm diameter, 5-μm pore polycarbonate Transwell culture insert. The same media (600 μL) with or without chemokine were placed in the lower chamber. Chemotaxis proceeded for 2 hours at 37°C in humidified air with 5% CO2. CXCL12, macrophage inflammatory protein 1β (MIP-1β)/CCL4 (from Dr F. Baleux) and regulated on activation normal T expressed and secreted (RANTES)/CCL5 (Sigma) were used at 30 nM and CCL21 at 60 nM. AMD3100 (AnorMED, Langley, Canada) was used at 1 μM to inhibit CXCR4-dependent signaling. The fraction of cells migrating across the polycarbonate membrane was calculated as follows: {[(number of cells migrating to the lower chamber in response to chemokine) - (number of cells migrating spontaneously)] / number of cells added to the upper chamber at the start of the assay} × 100.

Actin polymerization assays were performed as described23 using CXCL12 at 30 nM and CCL21 at 60 nM. Intracellular F-actin content was measured in fixed cells using the fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–labeled phalloidin and was expressed as follows: (MFI after addition of chemokine / MFI before addition of chemokine) × 100. MFI values assessed before addition of ligand were arbitrarily set at 100%.

HEK-293T cells (ATCC) were transiently transfected using a phosphate calcium method with CXCR4-derived cDNAs. Crude membranes from these cells were assessed for 35S-GTPγS (GTP analog guanosine-5′-(γ-thio)-triphosphate) binding as described.34 EC50 (half maximal effective concentration) was determined with the GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) using nonlinear regression applied to a sigmoidal dose-response model.

Histopathologic studies

Wart and condyloma biopsies from patients P1 and P2 (4 independent samples) and 4 patients without WHIM were obtained. Biopsies from healthy skin, a non-HPV–related proliferative lesion (seborrheic keratosis), 2 epidermoid carcinomas, and inflammatory skin lesions (cutaneous lupus and dermatomyositis) were studied in parallel. Immunohistochemistry was performed in paraffin-embedded sections as previously described,35 using the anti-CXCL12 (clone K15C, IgG2a isotype Ig) and anti-CXCR4 (clone 6H8, IgG1 isotype Ig) mAbs. Binding of mAbs was detected by immunoperoxidase staining using diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate, and sections were subsequently counterstained in Gill hematoxylin. Control sections were similarly processed with isotype-matched mouse IgG instead of primary mAbs. Images were obtained on a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) equipped with standard optic objectives at the indicated magnifications (10-60 ×, apertures 0.25-1.4) and were directly digitalized using a SpotRT CCD camera and Spot 4.0.4 software (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyzes consisted in unpaired 2-tailed Student t tests and were carried out with the Prism software (GraphPad Software).

Results

Patients with WHIM syndrome present a genetic heterogeneity in the CXCR4 locus

We identified that the siblings P1 and P2, who inherited the autosomal dominant haplotype from their father (Figure 1A), carry a mutation in the CXCR4 ORF. According to recent reports,24,36 this punctual heterozygous mutation (Figure 1B, right panel) leads to a partial deletion of the CXCR4 C-tail (WHIM1013; Figure 1C). Patient P3 inherited the autosomal dominant haplotype from her father, while patient P4 is the fourth child of healthy, nonconsanguineous parents and might constitute a sporadic case of the syndrome (Figure 1A). In both patients P3 and P4, 1 single CXCR4 cDNA product was amplified using the 3′–step-out rapid amplification technology, and its sequence was found to be wild type as illustrated for patient P3 in Figure 1B (left panel). These 2 pedigrees were called “WHIMwt” in reference to the absence of mutation in the CXCR4 ORF. We found that the levels of CXCR4 cell surface expression on WHIMwt lymphocytes were similar to those detected either on WHIM1013 or control ones (Figure 1D). This result is suggestive of a normal production and stability of CXCR4 mRNA in WHIMwt lymphocytes. Functional studies were next set up to investigate CXCL12-induced signaling in WHIMwt and WHIM1013 lymphocytes.

Impaired CXCL12-induced internalization of CXCR4 in lymphocytes from patients with WHIM

On the basis of the requirement of the C-tail integrity for CXCR4 internalization,33,37-40 we speculated that WHIM-associated C-tail truncated receptors (CXCR4m) might be impaired in their ability to be internalized in response to CXCL12. Therefore, internalization of CXCR4 in response to CXCL12 was investigated in circulating T lymphocytes from healthy subjects and patients P1 and P2. To assess CXCR4 cell surface expression following CXCL12 stimulation, cells were washed in acidic buffer. This permitted us to remove CXCL12 bound to CXCR4 that would compete for the binding of the mAb 12G5 to the second extracellular loop of CXCR433,38,39 and, therefore, would mask detection of CXCR4 (Figure 2A). We found that, in sharp contrast to cells from healthy subjects (Figure 2A, left panel), the internalization of CXCR4 induced either by CXCL12 or PMA in T lymphocytes from patients P1 (Figure 2A, right panel) and P2 was markedly impaired (Figure 2B). Time-course analysis of CXCL12-promoted CXCR4 down-modulation indicated that the residual internalization in CD4+-gated T lymphocytes from patients was delayed relative to control cells (Figure 2C). Similar results were obtained in CD8+-gated T cells (data not shown).

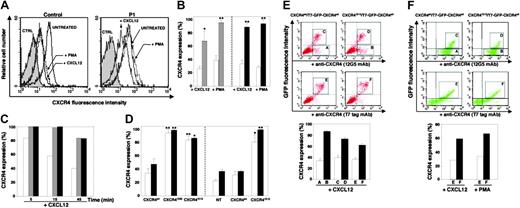

Altered CXCR4 internalization in WHIM1013 lymphocytes. (A) Cell surface expression levels of CXCR4 in CD4+-gated T cells from PBMCs of a healthy subject (control, left panel) or WHIM1013 patient P1 (right panel). CXCR4 levels were assessed using the 12G5 (empty histograms) or isotype control (CTRL, gray histograms) mAb. (B) CXCR4 cell surface expression in CD4+-gated T cells from PBMCs of WHIM1013 patients P1 (▦) and P2 (▪) or healthy subjects (□). *P < .05 and **P < .005 compared with healthy subjects. (C) Time course of CXCL12-promoted CXCR4 endocytosis in CD4+-gated T cells from patients P1 (▦) and P2 (▪) versus healthy subject (□). (D) CXCR4 cell surface expression in A0.01 T cells (left panel) or PBMCs from healthy individuals (right panel) nontransduced (NT) or transduced with the indicated CXCR4 variant receptors. □ indicates +CXCL12; ▪, +PMA. In untreated A0.01 T cells, the geometric MFI of CXCR4wt, CXCR41000, and CXCR41013 receptors were 30, 35, and 28, respectively. Analysis in PBMCs was assessed in CD4+-gated T cells. *P < .05 and **P < .005 compared with CXCR4wt-expressing A0.01 T cells or with NT T lymphocytes. Results, expressed as percentage of untreated cells, are from 3 independent experiments (mean ± SEM) (B,D) or from 1 representative experiment of 2 (C). (E) Cell surface expression of T7-GFP-CXCR4wt in CXCR4wt or CXCR41013 CHO cells either untreated (dot plot, top) or treated with CXCL12 (bottom). □ indicates CXCR4wt; ▪, CXCR41013. In untreated CHO cells, the geometric MFI of CXCR4wt GFP-/gate A), CXCR41013 GFP- (gate B), CXCR4wt GFP+ (gate C), and CXCR41013 GFP+ (gate D) were 47, 57, 63, and 61, respectively. Expression of T7-GFP-CXCR4wt is roughly comparable when coexpressed with CXCR4wt (geometric MFI = 150, gate E) or CXCR41013 (geometric MFI = 130, gate F). Analysis of CXCL12-promoted receptor endocytosis was performed in the cell gates defined earlier in the legend. Results (mean ± SEM) are representative of 2 determinations and are expressed as percentage of untreated cells. (F) Cell surface expression of T7-GFP-CXCR4wt in CD4+-gated T cells from PBMCs of a healthy individual transfected with CXCR4wt or CXCR41013 variant either untreated (dot plot, upper panel) or treated with CXCL12 or PMA (lower panel). □ indicates CXCR4wt; ▪, CXCR41013. In untreated CD4+-gated T cells, the geometric MFI of CXCR4 in gates A, B, C, and D were 195, 210, 620, and 580, respectively. Expression of T7-GFP-CXCR4wt is roughly comparable when coexpressed with CXCR4wt (geometric MFI = 260, gate E) or CXCR41013 (geometric MFI = 220, gate F). Analysis of CXCL12- or PMA-promoted receptor endocytosis was performed in cell gates defined above. Results are from 1 representative experiment of 2 and are expressed as percentage of untreated cells.

Altered CXCR4 internalization in WHIM1013 lymphocytes. (A) Cell surface expression levels of CXCR4 in CD4+-gated T cells from PBMCs of a healthy subject (control, left panel) or WHIM1013 patient P1 (right panel). CXCR4 levels were assessed using the 12G5 (empty histograms) or isotype control (CTRL, gray histograms) mAb. (B) CXCR4 cell surface expression in CD4+-gated T cells from PBMCs of WHIM1013 patients P1 (▦) and P2 (▪) or healthy subjects (□). *P < .05 and **P < .005 compared with healthy subjects. (C) Time course of CXCL12-promoted CXCR4 endocytosis in CD4+-gated T cells from patients P1 (▦) and P2 (▪) versus healthy subject (□). (D) CXCR4 cell surface expression in A0.01 T cells (left panel) or PBMCs from healthy individuals (right panel) nontransduced (NT) or transduced with the indicated CXCR4 variant receptors. □ indicates +CXCL12; ▪, +PMA. In untreated A0.01 T cells, the geometric MFI of CXCR4wt, CXCR41000, and CXCR41013 receptors were 30, 35, and 28, respectively. Analysis in PBMCs was assessed in CD4+-gated T cells. *P < .05 and **P < .005 compared with CXCR4wt-expressing A0.01 T cells or with NT T lymphocytes. Results, expressed as percentage of untreated cells, are from 3 independent experiments (mean ± SEM) (B,D) or from 1 representative experiment of 2 (C). (E) Cell surface expression of T7-GFP-CXCR4wt in CXCR4wt or CXCR41013 CHO cells either untreated (dot plot, top) or treated with CXCL12 (bottom). □ indicates CXCR4wt; ▪, CXCR41013. In untreated CHO cells, the geometric MFI of CXCR4wt GFP-/gate A), CXCR41013 GFP- (gate B), CXCR4wt GFP+ (gate C), and CXCR41013 GFP+ (gate D) were 47, 57, 63, and 61, respectively. Expression of T7-GFP-CXCR4wt is roughly comparable when coexpressed with CXCR4wt (geometric MFI = 150, gate E) or CXCR41013 (geometric MFI = 130, gate F). Analysis of CXCL12-promoted receptor endocytosis was performed in the cell gates defined earlier in the legend. Results (mean ± SEM) are representative of 2 determinations and are expressed as percentage of untreated cells. (F) Cell surface expression of T7-GFP-CXCR4wt in CD4+-gated T cells from PBMCs of a healthy individual transfected with CXCR4wt or CXCR41013 variant either untreated (dot plot, upper panel) or treated with CXCL12 or PMA (lower panel). □ indicates CXCR4wt; ▪, CXCR41013. In untreated CD4+-gated T cells, the geometric MFI of CXCR4 in gates A, B, C, and D were 195, 210, 620, and 580, respectively. Expression of T7-GFP-CXCR4wt is roughly comparable when coexpressed with CXCR4wt (geometric MFI = 260, gate E) or CXCR41013 (geometric MFI = 220, gate F). Analysis of CXCL12- or PMA-promoted receptor endocytosis was performed in cell gates defined above. Results are from 1 representative experiment of 2 and are expressed as percentage of untreated cells.

To authenticate the causative role played by the CXCR4 mutations in the impaired endocytosis of the receptors, we expressed either CXCR4wt or the CXCR4m receptors (CXCR41000 or CXCR41013) in the A0.01 T-cell lines that do not express CXCR4 or in lymphocytes from healthy donors (Figure 2D). In A0.01 T cells, our results indicate that the CXCR4m receptors were disabled to undergo endocytosis in response to CXCL12 or PMA, while CXCR4wt was, as expected, extensively internalized (Figure 2D, left panel). Expression of CXCR4m in lymphocytes from healthy subjects is shown in Figure 2D, right panel. CXCL12- and PMA-induced endocytosis of receptors were found to be impaired in cells transduced with CXCR41013 (Figure 2D, right panel) and CXCR41000 (data not shown), while they remained preserved in nontransduced or CXCR4wt-transduced lymphocytes. These findings show that expression of CXCR4m in T cells reproduces the CXCR4 dysfunctions observed in WHIMm leukocytes. This suggests the functional prevalence of the mutant CXCR4 receptor over its wild-type counterpart in WHIMm leukocytes.

We then investigated whether this phenomenon might be attributed to the predominant expression of the mutant CXCR4 receptor at the cell surface of WHIMm leukocytes. We stably expressed in CHO cells, which lack endogenous CXCR4 expression, either CXCR4wt or CXCR41013 receptors following a lentiviral-based strategy. These cells were then transiently transfected with a plasmid encoding T7-GFP-CXCR4wt. T7 and green fluorescent protein (GFP) tags fused at the receptor N-terminus of this chimera receptor permitted us to distinguish selectively CXCR4wt expression when it coexists with CXCR41013 (Figure 2E).

Staining of the T7-Tag revealed that the cell surface expression of the CXCR4wt chimera was not altered when coexpressed with the mutated CXCR41013 receptor (GFP+-gated cells in Figure 2E, gates E and F). Conversely, we controlled that untagged CXCR4wt and CXCR41013 displayed similar cell-surface expression in the presence of the chimera (GFP+-gated cells in Figure 2E, gates C and D). However, we found that the CXCR4wt chimera receptor became refractory to CXCL12-induced internalization when coexpressed with CXCR41013 (Figure 2E, lower panel). Similar experiments performed using PBMCs from healthy subjects, coexpressing after nucleoporation the CXCR4wt chimera with either CXCR41013 or CXCR4wt (in a 1:1 ratio), are shown in Figure 2F. Expression levels of the CXCR4wt chimera in CD4+-gated T cells were roughly comparable when coexpressed with CXCR4wt (upper panel, gate E) or CXCR41013 (upper panel, gate F). Again, we found that CXCR41013 expression impaired CXCR4wt chimera endocytosis in response to both CXCL12 and PMA (Figure 2F, lower panel). Overall, these findings highly suggest that the functional prevalence of CXCR41013 we speculated in WHIMm leukocytes cannot be attributed to its accumulation at the cell surface. Rather, our results make it likely that CXCR41013 alters the functioning of the wild-type receptor by means of a transdominant-negative effect.

We next investigated whether the aberrant pattern of CXCR4 endocytosis relates specifically to the presence of a truncated CXCR4 receptor or extends to leukocytes from aWHIMwt patient. Figure 3A-B illustrates the defective CXCL12-promoted CXCR4 internalization in CD4+-gated T cells from patients P3 and P4. In contrast, CXCR4 was readily internalized after PMA treatment, as observed in lymphocytes from healthy individuals, including the parents of patient P4 (Figure 3B). We also noticed that CCL21 (Figure 3B) and CCL4 (data not shown) efficiently promoted internalization of the chemokine receptors CCR7 and CCR5, respectively, in both patient P4 and control cells. Additionally, in skin fibroblasts from patient P3 with WHIMwt, we found that CXCR4 was refractory to CXCL12-promoted internalization but remained fully sensitive to PMA stimulation (data not shown).

Defective CXCR4 internalization and desensitization in WHIMwt lymphocytes. (A-B) CXCL12- and PMA-promoted CXCR4 internalization in CD4+-gated T cells from WHIMwt patients P3 (A) and P4 (B) and healthy subjects (□, and patient P4's mother ▦ and father ▨). (B) CCL21-promoted CCR7 endocytosis in CD4+-gated T cells from the patient P4 and healthy subjects is shown. Values, expressed as percentage of unstimulated cells, are from 3 independent experiments (mean ± SEM). *P < .05 compared with healthy subjects. (C-D) CXCL12-triggered actin polymerization in CD4+-gated T lymphocytes from WHIM patients P3 (C, left panel) and P4 (D) and healthy individuals (□ and patient P4's mother ▵ and father ○). Panel C (right) shows kinetics of actin polymerization following CCL21 stimulation. Arrows indicate chemokine stimulation. The results displayed are from 1 representative experiment of 2.

Defective CXCR4 internalization and desensitization in WHIMwt lymphocytes. (A-B) CXCL12- and PMA-promoted CXCR4 internalization in CD4+-gated T cells from WHIMwt patients P3 (A) and P4 (B) and healthy subjects (□, and patient P4's mother ▦ and father ▨). (B) CCL21-promoted CCR7 endocytosis in CD4+-gated T cells from the patient P4 and healthy subjects is shown. Values, expressed as percentage of unstimulated cells, are from 3 independent experiments (mean ± SEM). *P < .05 compared with healthy subjects. (C-D) CXCL12-triggered actin polymerization in CD4+-gated T lymphocytes from WHIM patients P3 (C, left panel) and P4 (D) and healthy individuals (□ and patient P4's mother ▵ and father ○). Panel C (right) shows kinetics of actin polymerization following CCL21 stimulation. Arrows indicate chemokine stimulation. The results displayed are from 1 representative experiment of 2.

Impaired CXCR4 desensitization in WHIM patient lymphocytes

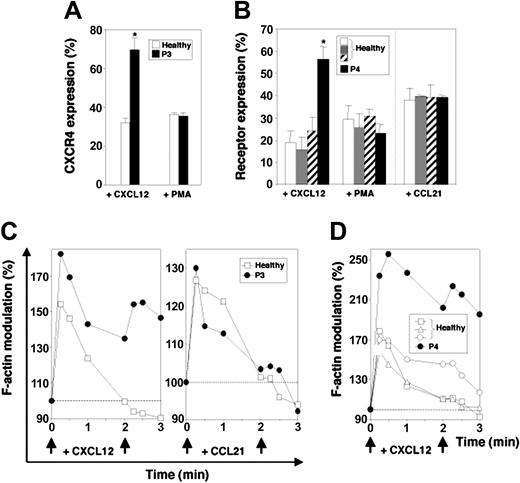

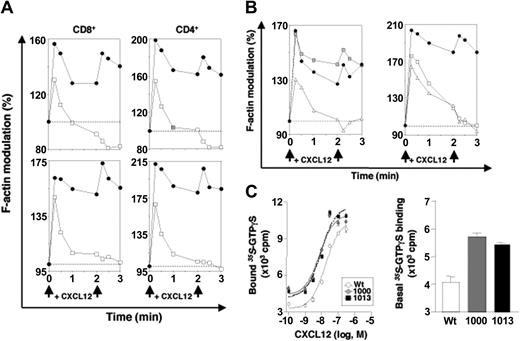

Defective CXCL12-dependent CXCR4 endocytosis suggested an impairment of homologous desensitization, an adaptive process that precludes a protracted coupling of the stimulated receptor to heterotrimeric Gαβγ proteins. To address this issue, we measured polymerization of actin monomers into F-actin filaments, a response indicative of receptor-dependent G-protein activation.41,42 In control CD4+-gated T lymphocytes, a rapid and transient rise of F-actin was observed after the first stimulation with CXCL12 but no response after the second stimulation, indicating that desensitization had occurred (Figure 3C-D, open symbols). By contrast, in CD4+-gated T lymphocytes from WHIMwt patients P3 (Figure 3C, left panel, •) and P4 (Figure 3D, •), actin polymerization was protracted after the first stimulation with CXCL12, and a rise was also observed after the second stimulation. However, the response to CCL21 was similar in control and patient cells (Figure 3C). Similar results were obtained in CD8+-gated T cells (data not shown). Regarding the WHIM1013 pedigree, we also demonstrated that CXCR4 desensitization was impaired in both CD4+- and CD8+-gated T lymphocytes from patients P1 and P2 (Figure 4A, •). Additionally, this functional anomaly was also evidenced in CXCR4-negative T-cell lines or control T lymphocytes expressing the mutant CXCR4m receptors (Figure 4B, left and right panels, respectively).

Impaired desensitization of truncated CXCR4m receptors. (A) CXCL12-triggered actin polymerization in CD8+-gated (left panels) and CD4+-gated (right panels) T cells from WHIM1013 patients P1 (top row, •) and P2 (bottom row, •) or from healthy donors (□). (B) Kinetics of CXCL12-triggered actin polymerization in A0.01 T cells (left panel) or in CD4+-gated T lymphocytes (right panel) nontransduced (NT) or transduced with the indicated CXCR4 variants (▵, CXCR4wt; ▦, CXCR41000; •, CXCR41013; □, NT). (A-B) Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (C) GTPγS binding assays to membranes from HEK-293T cells expressing at similar levels CXCR4wt (left panel, ○; right panel, □), CXCR41000 (left panel,  ; right panel, ▦), or CXCR41013 (▪) (geometric MFI for the aforementioned receptors were 11.2, 12.3, and 10.5, respectively). Membranes were treated with the indicated concentrations of CXCL12 (left panel) or left untreated (right panel). Data are mean ± SEM of triplicate determinations. Deduced EC50 values of the experiment of 3 independent determinations were 17 nM for CXCR4wt, 7 nM for CXCR41000, and 9 nM for CXCR41013.

; right panel, ▦), or CXCR41013 (▪) (geometric MFI for the aforementioned receptors were 11.2, 12.3, and 10.5, respectively). Membranes were treated with the indicated concentrations of CXCL12 (left panel) or left untreated (right panel). Data are mean ± SEM of triplicate determinations. Deduced EC50 values of the experiment of 3 independent determinations were 17 nM for CXCR4wt, 7 nM for CXCR41000, and 9 nM for CXCR41013.

Impaired desensitization of truncated CXCR4m receptors. (A) CXCL12-triggered actin polymerization in CD8+-gated (left panels) and CD4+-gated (right panels) T cells from WHIM1013 patients P1 (top row, •) and P2 (bottom row, •) or from healthy donors (□). (B) Kinetics of CXCL12-triggered actin polymerization in A0.01 T cells (left panel) or in CD4+-gated T lymphocytes (right panel) nontransduced (NT) or transduced with the indicated CXCR4 variants (▵, CXCR4wt; ▦, CXCR41000; •, CXCR41013; □, NT). (A-B) Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (C) GTPγS binding assays to membranes from HEK-293T cells expressing at similar levels CXCR4wt (left panel, ○; right panel, □), CXCR41000 (left panel,  ; right panel, ▦), or CXCR41013 (▪) (geometric MFI for the aforementioned receptors were 11.2, 12.3, and 10.5, respectively). Membranes were treated with the indicated concentrations of CXCL12 (left panel) or left untreated (right panel). Data are mean ± SEM of triplicate determinations. Deduced EC50 values of the experiment of 3 independent determinations were 17 nM for CXCR4wt, 7 nM for CXCR41000, and 9 nM for CXCR41013.

; right panel, ▦), or CXCR41013 (▪) (geometric MFI for the aforementioned receptors were 11.2, 12.3, and 10.5, respectively). Membranes were treated with the indicated concentrations of CXCL12 (left panel) or left untreated (right panel). Data are mean ± SEM of triplicate determinations. Deduced EC50 values of the experiment of 3 independent determinations were 17 nM for CXCR4wt, 7 nM for CXCR41000, and 9 nM for CXCR41013.

The increased magnitude of CXCL12-promoted F-actin peak observed in all patient lymphocytes (Figures 3C-D and 4A) was reproduced both in A0.01 T-cell lines and in normal T lymphocytes expressing CXCR4m (Figure 4B). This finding might reflect an increased ability of WHIM-associated CXCR4 to activate G-proteins. We thus developed HEK-293T cell lines expressing similar amounts of CXCR4wt or CXCR4m (Figure 4) to investigate CXCL12-induced activation of G-proteins using a GTPγS binding assay.43 As shown in Figure 4C (left panel), the half-maximal effective concentrations for CXCL12 were about half for CXCR4m-than for CXCR4wt-expressing membranes, indicating that the ligand is a more potent agonist toward the truncated than the wild-type receptor. Additionally, a more efficient activation of G-proteins by CXCR4m was observed either in the absence or in the presence of CXCL12 (Figure 4C, right and left panels, respectively). Thus, the enhanced responsiveness of WHIM-associated CXCR4 to CXCL12 is likely to be the consequence of an improved activation of receptor-associated G-proteins.

Enhanced CXCL12-promoted chemotaxis of WHIM patient leukocytes

Sustained agonist-induced G-protein–dependent signaling and impaired CXCR4 desensitization predicted magnified responsiveness of WHIM leukocytes to CXCL12. This possibility was investigated using a chemotaxis assay. Leukocytes from WHIMwt (Figure 5A) and WHIM1013 (Figure 5B) patients displayed a stronger chemotactic response toward CXCL12 relative to control cells. This enhanced cell migration in response to CXCL12 was totally inhibited by the specific CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 (Figure 5B, left panel). CCR5- and CCR7-dependent migrations were observed to be in the same range for WHIM and control leukocytes. We reproduced the exacerbated CXCL12-induced chemotaxis of WHIM leukocytes with A0.01 T cells expressing CXCR4m (Figure 5C). As compared with controls, CXCR4m-expressing A0.01 T cells displayed stronger migratory responses at low concentrations of ligand, indicating a higher efficiency of CXCL12 toward these cells.

Exacerbated CXCL12-induced chemotaxis of WHIM leukocytes. (A) CXCL12-, CCL21-, CCL4-, or CCL5-induced migration of PBMCs from patients P3 (left panel, ▪) and P4 (right panel, ▪) and healthy donors (□, and patient P4's mother [▦] and father [▨]). Transmigrated cells recovered in the lower chamber were counted by flow cytometry with gating on forward and side scatter to exclude debris and monocytes. (B) CXCL12-promoted chemotaxis of PBMCs from WHIM1013 patients P1 (left panel, ▦) and P2 (right panel, ▪) or healthy individuals (□). Inhibition of cell migration by AMD3100 added in both chambers and chemotaxis in response to CCL4 are shown. (C) Dose-dependent CXCL12-induced chemotaxis of A0.01 T cells transduced with the indicated CXCR4 variants (□, CXCR4wt; ▦, CXCR41000; ▪, CXCR41013). Parental A0.01 T-cell line was consistently unresponsive to CXCL12. (A-C) Results (mean ± SEM) are from 3 independent experiments and are expressed as percentage of input cells that migrated to the lower chamber. *P < .05 and **P < .005 compared with leukocytes from healthy subjects or with CXCR4wt-expressing A0.01 T cells.

Exacerbated CXCL12-induced chemotaxis of WHIM leukocytes. (A) CXCL12-, CCL21-, CCL4-, or CCL5-induced migration of PBMCs from patients P3 (left panel, ▪) and P4 (right panel, ▪) and healthy donors (□, and patient P4's mother [▦] and father [▨]). Transmigrated cells recovered in the lower chamber were counted by flow cytometry with gating on forward and side scatter to exclude debris and monocytes. (B) CXCL12-promoted chemotaxis of PBMCs from WHIM1013 patients P1 (left panel, ▦) and P2 (right panel, ▪) or healthy individuals (□). Inhibition of cell migration by AMD3100 added in both chambers and chemotaxis in response to CCL4 are shown. (C) Dose-dependent CXCL12-induced chemotaxis of A0.01 T cells transduced with the indicated CXCR4 variants (□, CXCR4wt; ▦, CXCR41000; ▪, CXCR41013). Parental A0.01 T-cell line was consistently unresponsive to CXCL12. (A-C) Results (mean ± SEM) are from 3 independent experiments and are expressed as percentage of input cells that migrated to the lower chamber. *P < .05 and **P < .005 compared with leukocytes from healthy subjects or with CXCR4wt-expressing A0.01 T cells.

As myelokathexis constitutes a prominent clinical manifestation of the syndrome, we also examined the sensitivity of PMNs from WHIMwt and WHIM1013 patients to CXCL12. Similarly to patient lymphocytes, PMNs displayed impaired CXCR4 desensitization (Figure 6A,C), and a markedly increased chemotaxis in response to CXCL12 (Figure 6B,D).

Impaired CXCR4 signaling in WHIM PMNs. (A,C) CXCL12-triggered actin polymerization in overnight-cultured PMNs from WHIMwt patient P4 (A, •) or WHIM1013 patient P2 (C, •) compared with those from healthy donors (□ and patient P4's mother [▵] and father [○]). Results are from 1 representative experiment of 3. (B,D) CXCL12-induced chemotaxis of PMNs from patients P4 (B, ▪) and P2 (D, ▪) were compared with those of cells from healthy donors (□, and patient P4's mother [▦] and father [▨]). Inhibition of CXCL12-induced chemotaxis by addition of AMD3100 in both chambers is shown in panel B. Results (mean ± SEM) are from 3 independent experiments and are expressed as percentage of input PMNs that migrated to the lower chamber. **P < .005 compared with PMNs from healthy subjects.

Impaired CXCR4 signaling in WHIM PMNs. (A,C) CXCL12-triggered actin polymerization in overnight-cultured PMNs from WHIMwt patient P4 (A, •) or WHIM1013 patient P2 (C, •) compared with those from healthy donors (□ and patient P4's mother [▵] and father [○]). Results are from 1 representative experiment of 3. (B,D) CXCL12-induced chemotaxis of PMNs from patients P4 (B, ▪) and P2 (D, ▪) were compared with those of cells from healthy donors (□, and patient P4's mother [▦] and father [▨]). Inhibition of CXCL12-induced chemotaxis by addition of AMD3100 in both chambers is shown in panel B. Results (mean ± SEM) are from 3 independent experiments and are expressed as percentage of input PMNs that migrated to the lower chamber. **P < .005 compared with PMNs from healthy subjects.

Expression and distribution of CXCL12 in warts and condylomata from patients with WHIM

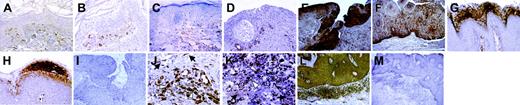

To gain knowledge on the relationship between the lack of CXCR4-signaling attenuation and the profusion and persistence of HPV lesions observed in patients with WHIM, we investigated the expression of CXCL12 in wart and condyloma biopsies from these patients. CXCL12 was not detected in the epidermis of healthy skin, benign proliferative lesions (seborrheic keratosis), inflammatory skin lesions, or epidermoid carcinomas (Figure 7A-D). In addition, no CXCL12 staining was observed in skin lesions induced by herpes virus (Kaposi) or poxvirus (Molluscum contagiosum; data not shown). In striking contrast, 3 of 4 samples from patients P1 and P2, found to be positive for HPV (immunostaining of the capside L1 HPV protein; data not shown), displayed strong CXCL12 immunostaining in keratinocytes (Figure 7E-F). Similarly to WHIM HPV lesions, keratinocytes from warts of patients without WHIM (4 samples from 4 patients), free of concomitant infections by other pathogens, also displayed, mainly in the granular layer, abundant CXCL12 expression (Figure 7G-H). The expression pattern of CXCL12 in the dermis was similar to that previously observed in healthy and inflammatory skin and included blood vessel endothelia, sweat glands, scattered fibroblasts, and large mononuclear leukocytes.35,44,45 In both WHIM and non-WHIM HPV lesions, fibroblasts and a fraction of mononuclear leukocytes with dendritic cell–like morphology expressed abundant CXCL12 (Figure 7J-K). As previously reported for healthy and inflammatory skin,35 CXCR4 was uniformly detected in epidermal keratinocytes, endothelium, and infiltrating cells in all WHIM and non-WHIM warts and condylomata (Figure 7L). Absence of labeling using IgG2a and IgG1 nonrelevant isotype controls supports the specificity of staining for CXCL12 and CXCR4, respectively (Figure 7I,M).

Expression of CXCL12 in HPV lesions from patient with and without WHIM. CXCL12 immunostaining of control skin samples: healthy skin (A), seborrheic keratosis (B), inflammatory skin (C), and epidermoid carcinoma (D). CXCL12 expression in WHIM wart epidermis (E), WHIM dysplastic condyloma epidermis (F), non-WHIM wart (G), non-WHIM condyloma (H). WHIM wart epidermis (same specimen as in panel E) immunostained with IgG2a isotype-matched control antibody (Ab) (I). CXCL12 expression in non-WHIM (J) and WHIM (K) dermal mononuclear infiltrates. Cells with fibroblast (arrows) or dendritic cell morphology (arrowheads) are shown (J-K). CXCR4 immunostaining of WHIM wart dermis and epidermis (L). The same specimen was similarly processed with IgG1 isotype-matched control Ab (M). Original magnification, × 400 (A-C,G,H), × 200 (D-F,I), × 600 (J-K), × 100 (L-M).

Expression of CXCL12 in HPV lesions from patient with and without WHIM. CXCL12 immunostaining of control skin samples: healthy skin (A), seborrheic keratosis (B), inflammatory skin (C), and epidermoid carcinoma (D). CXCL12 expression in WHIM wart epidermis (E), WHIM dysplastic condyloma epidermis (F), non-WHIM wart (G), non-WHIM condyloma (H). WHIM wart epidermis (same specimen as in panel E) immunostained with IgG2a isotype-matched control antibody (Ab) (I). CXCL12 expression in non-WHIM (J) and WHIM (K) dermal mononuclear infiltrates. Cells with fibroblast (arrows) or dendritic cell morphology (arrowheads) are shown (J-K). CXCR4 immunostaining of WHIM wart dermis and epidermis (L). The same specimen was similarly processed with IgG1 isotype-matched control Ab (M). Original magnification, × 400 (A-C,G,H), × 200 (D-F,I), × 600 (J-K), × 100 (L-M).

Discussion

Our study shows that primary lymphocytes and neutrophils from individuals with clinical features of the WHIM syndrome share functional alterations of CXCR4-mediated responses. We provide original evidence that such anomalies do not necessarily depend on the occurrence of a C-terminally truncated form of CXCR4, as they are also observed in WHIM leukocytes expressing only wild-type CXCR4 receptors. Refractoriness of CXCR4 to be desensitized and internalized together with increased G-protein–dependent signaling in response to CXCL12 are characteristic biologic manifestations we found in all patient leukocytes. We propose that the resulting, abnormally sustained CXCR4 activity in WHIM lymphocytes and neutrophils might account for the peculiar association of lymphopenia and myelokathexis with this genetic disorder.

Agonist-induced GPCR internalization generally relies on phosphorylation of the C-tail that in turn promotes binding of β-arrestins to phosphorylated receptors.46 Accordingly, CXCR4 internalization depends on C-tail Ser/Thr residues that are phosphorylated in response to PMA and CXCL12 via protein kinase C (PKC) or G-protein–coupled receptor kinases (GRKs).40 Thus, removal of Ser338/Ser339 and Ser341/Thr342 couples and Ser344 in C-tail–truncated CXCR4m is likely to be responsible for the impaired endocytosis of these receptors in WHIM lymphocytes. Yet, the residual marginal endocytosis of CXCR4m upon ligand stimulation could be accounted for by the preserved Ser324 and Ser325 residues.40

Ectopic expression of CXCR41013 in T cells reproduces qualitatively and quantitatively the CXCR4 dysfunctions observed in WHIM1013 leukocytes. This finding provides direct evidence for the etiologic role of the C-tail–truncated CXCR4 and strongly suggests a prevalence of the mutant CXCR4 functioning over that of the wild-type receptor. CXCR4 is known to spontaneously internalize at high rates, with a marginal part being recycled at the cell surface.47-49 Thus, as a first assumption, we speculated that the default of CXCR41013 to be internalized cause its predominance at the plasma membrane. However, our results with the T7-GFP-CXCR4wt chimera receptor (Figure 2E-F) challenge this possibility as expression of CXCR41013 does not affect cell surface expression of CXCR4wt and vice versa. Of importance, we clearly demonstrate that CXCR41013 alters the functioning of its wild-type counterpart in a transdominant-negative manner. These findings provide clues on the molecular mechanisms that account for the functional defect we report in WHIM1013 leukocytes that carry heterozygous mutation of CXCR4. It is known that CXCR4 forms constitutive oligomers.50,51 Similarly, it is likely that CXCR41013/CXCR4wt hetero-oligomers exist in WHIM1013 leukocytes, thereby permitting CXCR41013 to hijack CXCR4wt functioning by a transdominant mechanism. Resonance energy transfer experiments with distinctly tagged mutant and wild-type CXCR4 receptors will help to elucidate the intimate mechanisms of this phenomenon.

We propose that the functional anomalies of CXCR4 we identified in WHIMwt leukocytes likely rely on an aberrant downstream partner with some degree of selective interaction with CXCR4. This assumption is reinforced by our observations that first, CXCR4wt, when ectopically expressed in primary fibroblasts from WHIMwt patients, became defective in CXCL12-promoted endocytosis (data not shown). Second, CCR7 and CCR5 internalization and desensitization were unaffected in WHIMwt lymphocytes. Finally, the fact that CXCR4 in WHIMwt lymphocytes internalizes poorly in response to CXCL12 but remains fully susceptible to PMA strongly suggests that the endocytic pathway downstream of the β-arrestin recruitment is preserved. Thus, the impaired internalization of CXCR4wt in response to CXCL12 points to the existence of a mutated or down-regulated protein restricted to the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis, which might affect the agonist-dependent phosphorylation and/or the coupling of the C-tail to the endocytic pathway. Potential protein candidates include GRKs, as it appears from recent works that distinct GRKs do not interact with CXCR4 with equal efficiency.42,52,53 In addition to GRKs, evidence accumulates that proteins can associate with the C-ter domain of GPCRs,54 thereby regulating their activity. Accordingly, an unknown scaffolding protein might selectively participate in the attenuation of CXCR4 signaling.

The refractoriness of CXCR4 to desensitization is a prominent characteristic in both WHIMwt and WHIMm leukocytes, from which results the enhanced efficiency of CXCR4 receptors to stimulate G-proteins. Because chemotaxis relies on the activation of G-protein βγ subunits,55 both the enhanced and sustained CXCR4-associated G-protein–dependent signaling in WHIM leukocytes could account for their more pronounced migration toward CXCL12 gradients. Our data are in keeping with the previously reported increased cell motility triggered by other chemokine receptors (ie, CCR2b, CCR5, CXCR2) that are refractory to desensitization.56-59 A recent study also reports an increased CXCL12 chemotactic response of leukocytes from WHIM patients carrying CXCR4 mutations.36 However, it is unclear why these receptors were not defective in desensitization and internalization, as they lack the Ser residues critical for agonist-induced endocytosis.40 These divergent observations are even more puzzling since the ectopic expression of CXCR4m, either in the CXCR4-negative A0.01 T-cell line or in normal lymphocytes, recreates in our hands the same set of CXCR4-related anomalies we observed in primary cells from patients with WHIM. However, while we used freshly isolated WHIMm leukocytes, Gulino et al36 performed experiments with long-term IL-2–expanded leukocytes. These different methodologic approaches may account for the discrepancies between the 2 groups regarding CXCR4 endocytosis and desensitization.

The correlation between altered CXCR4 signaling and the profusion of HPV lesions in patients with WHIM, however, remains intriguing. In light of reported observations and our current findings, several hypotheses can be considered. As previously proposed,24 the profusion of HPV-induced lesions could be accounted by a selective defect of anti-HPV effector-T lymphocytes due to the presence of a C-tail–truncated CXCR4. Although normal T-lymphocyte functions are observed in the patients described here, and in other reports,24,25,60 the paucity of anti-HPV responses and the marked T lymphopenia could contribute to the attenuation of the specific antiviral activity. Moreover, the aberrant CXCR4 signaling in WHIM patient cells could enhance some immune escape mechanisms proposed for HPV infection.61 An alternative hypothesis to the immune-specific deficiency is the possibility that infiltrating leukocytes, at the sites of HPV infection, would be instrumental for the development of extensive verrucosis. Indeed, in mouse models keratinocyte hyperproliferation, transformation, and metastasis elicited by HPV-16 oncogenes largely depend on the presence of infiltrating leukocytes with the capacity to secrete matrix metalloprotease-9.62 The production of this enzyme is induced by CXCL12.63,64 Thus, in patients with WHIM, CXCL12 secreted in the dermis could favor the development of HPV-induced lesions through the sustained activation of CXCR4 in leukocytes. This mechanism could be amplified by the intriguing and previously unreported production of CXCL12 from keratinocytes in HPV-induced lesions. Further work is required to determine the relevance of immune specific and inflammatory mechanisms in the genesis of the profuse HPV clinical infections in the WHIM syndrome.

CXCL12/CXCR4 is not only critical for homing and retention of hematopoietic progenitor CD34+ cells (HPCs) in the BM,15,65,66 but it is also essential for the regulation of neutrophil mobilization from the BM.67,68 Manifold convergent observations support this notion. First, neutrophils activated by in vivo administration of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) release elastase,69 a protease that selectively degrades both CXCL12 and CXCR4 amino-terminus and prevents CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling.70 Injection of G-CSF induces egress of granulocytes from BM, whereas blocking of CXCL12 prevents BM relocalization of senescent, circulating neutrophils.67 Finally, the administration to human healthy volunteers of nonpeptidic CXCR4 antagonists mobilizes CD34+ HPCs and leukocytes, among which band-form neutrophils witness recent egress from the BM.71 We anticipate that the sustained CXCR4 activation observed in WHIM PMNs might strongly impair egress of mature neutrophils from the BM and force relocalization of circulating aged neutrophils to the BM. This mechanism might account for myelokathexis in patients with WHIM. While BM lymphopoiesis is preserved in the WHIM syndrome, the patients show a marked lymphopenia. The sustained CXCR4-dependent signaling could also affect the egress of mature lymphocytes from the BM. In this regard, the administration of CXCR4 antagonists mobilizes lymphocytes, including B cells, from the BM.71

Our findings provide a rationale for the incorporation of CXCR4 antagonist to the therapeutic arsenal used in the treatment of patients suffering with WHIM syndrome. By competing and limiting CXCR4 activation, antagonists would attenuate the aberrant signaling mediated by this receptor, raise the levels of circulating neutrophils, and thus reduce the number and severity of recurrent, bacterial infections in patients with WHIM.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, November 9, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2289.

Supported by fellowships and grants from Agence Nationale de Recherches Sur le SIDA (ANRS, France) and Ensemble contre le SIDA (SIDACTION, France) (K.B. and B.L.).

K.B. and B.L. contributed equally to this study.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Dr M. Thelen (Institute for Research in Biomedicine, Bellinzona, Switzerland) for critical reading of the manuscript and Pr J. L. Casanova (Laboratoire de Genetique Humaine des Maladies Infectieuses, Universite de Paris Rene Descartes-INSERM UMR550, Faculte de Medecine Necker-Enfants Malades) and Dr E. Solary (INSERM U517, Faculty of Medicine, Dijon, France) for helpful discussions. We thank Dr J. Donadieu and the French Register of Neutropenia for permanent support. We are grateful to Dr G. Gaibelet (IPBS/CNRS, Toulouse, France) and Dr P. Charneau (Unité de Virologie Moléculaire et de Vectorologie, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France) for providing us with the T7-GFP-CXCR4wt encoding plasmid and the pTRIP vector, respectively.

![Figure 5. Exacerbated CXCL12-induced chemotaxis of WHIM leukocytes. (A) CXCL12-, CCL21-, CCL4-, or CCL5-induced migration of PBMCs from patients P3 (left panel, ▪) and P4 (right panel, ▪) and healthy donors (□, and patient P4's mother [▦] and father [▨]). Transmigrated cells recovered in the lower chamber were counted by flow cytometry with gating on forward and side scatter to exclude debris and monocytes. (B) CXCL12-promoted chemotaxis of PBMCs from WHIM1013 patients P1 (left panel, ▦) and P2 (right panel, ▪) or healthy individuals (□). Inhibition of cell migration by AMD3100 added in both chambers and chemotaxis in response to CCL4 are shown. (C) Dose-dependent CXCL12-induced chemotaxis of A0.01 T cells transduced with the indicated CXCR4 variants (□, CXCR4wt; ▦, CXCR41000; ▪, CXCR41013). Parental A0.01 T-cell line was consistently unresponsive to CXCL12. (A-C) Results (mean ± SEM) are from 3 independent experiments and are expressed as percentage of input cells that migrated to the lower chamber. *P < .05 and **P < .005 compared with leukocytes from healthy subjects or with CXCR4wt-expressing A0.01 T cells.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/105/6/10.1182_blood-2004-06-2289/6/m_zh80060575400005.jpeg?Expires=1765900012&Signature=08Z3dNprE4tFIOd1u39UmmM5k7OWrX1nlczJgIlJkPaEnxnt8HSLMf5XQ~V0caiYeyRYfELmuQlGbDwJn2SXvok7EMYEtl7aSgkGzASX0PXtMQq9xcm1jqiYPZk4HBoLeA4CZsKQXpvSZh2o92g01zLErIdy-D~8g3UlUxKXQldw5UPKS8UxTulraRXTCSoWjIu1ZNhibQKfgvkXhqMveMd8kL-IWQzc32ZAZdCfN9mdwedFFw149w860bk5UPK-dRoy6muaZiXcqsota5Ojx29yBefLU~U8~93DFtF83mH~2UWpMFT3LkaaGRwH5le7m0FF-f0NSOwAxkTggbaOmA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 6. Impaired CXCR4 signaling in WHIM PMNs. (A,C) CXCL12-triggered actin polymerization in overnight-cultured PMNs from WHIMwt patient P4 (A, •) or WHIM1013 patient P2 (C, •) compared with those from healthy donors (□ and patient P4's mother [▵] and father [○]). Results are from 1 representative experiment of 3. (B,D) CXCL12-induced chemotaxis of PMNs from patients P4 (B, ▪) and P2 (D, ▪) were compared with those of cells from healthy donors (□, and patient P4's mother [▦] and father [▨]). Inhibition of CXCL12-induced chemotaxis by addition of AMD3100 in both chambers is shown in panel B. Results (mean ± SEM) are from 3 independent experiments and are expressed as percentage of input PMNs that migrated to the lower chamber. **P < .005 compared with PMNs from healthy subjects.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/105/6/10.1182_blood-2004-06-2289/6/m_zh80060575400006.jpeg?Expires=1765900012&Signature=nQ8bHJahxenR~DHfQsUyE7UrO4Witgef12tO4hUoFd7MXjOnbqQ6lkQWMa0ozjH56xEs49m0sKgVLEK7gHh226msebWDI56RiFbWJA6wFQQhNdMq3ASM5cGsqTeJoQVut00zc8UTfc4GIYwd9RJzKNHpLXB-4fCvRHI4ezz-~82r0St9WWD6Q3Z-jXugw4Du1FHbGzsIq~PNaogM9P7g~yOo-bJ0l8SOhs7bf6wlMihfr~ms~iW5tADotFyw5gf7LTzfdHKR7QZ-ayEoKrM1IEJkeLFzqp7r4eNw0NPM86G7GcOetGJkCunrZgqY9h6xnTer7BcIokg09yjwKkmM7w__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal