Abstract

Blood and endothelial cells arise in close association in developing embryos, possibly from a shared precursor, the hemangioblast, or as hemogenic endothelium. The transcription factor, Scl/Tal1 (stem cell leukemia protein), is essential for hematopoiesis but thought to be required only for remodeling of endothelium in mouse embryos. By contrast, it has been implicated in hemangioblast formation in embryoid bodies. To resolve the role of scl in endothelial development, we knocked down its synthesis in zebrafish embryos where early precursors and later phenotypes can be more easily monitored. With respect to blood, the zebrafish morphants phenocopied the mouse knockout and positioned scl in the genetic hierarchy. Importantly, endothelial development was also clearly disrupted. Dorsal aorta formation was substantially compromised and gene expression in the posterior cardinal vein was abnormal. We conclude that scl is especially critical for the development of arteries where adult hematopoietic stem cells emerge, implicating scl in the formation of hemogenic endothelium.

Introduction

During mammalian and avian embryogenesis, hematopoietic precursors arise in close association with the vasculature in the blood islands of the extra-embryonic yolk sac (YS) and in the ventral wall of the dorsal aorta (DA), in the aorta-gonads-mesonephros (AGM) region. These observations have led to the hypothesis that the 2 cell types arise from a common precursor, the hemangioblast. Coexpression of blood and endothelial genes, and the dependence of both lineages on several of them, are cited as evidence (for a review, see Keller1 ). In addition, single cells expressing the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor, flk1, isolated from embryoid bodies (EBs), differentiate in vitro into blast colonies, consisting of both hematopoietic and endothelial progenitors. These blast colony-forming cells (BL-CFCs) therefore represent the in vitro equivalent of the hemangioblast.2 However, the definitive lineage-labeling experiment to prove the in vivo existence of the hemangioblast has yet to be performed.

The concept of hemogenic endothelium has also acquired significant experimental support over recent years. Label targeted to endothelial cells (ECs) has been found later in the emerging clusters of cells containing the first hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in the DA (Jaffredo et al3 and references therein). Consistent with these data, purified ECs from both mouse and human embryos have been shown to possess hematopoietic potential.4-6 Taken together, the hemangioblast and hemogenic endothelium data strongly link hematopoiesis with at least a subset of EC development.

One gene, expressed in hemangioblast populations, is scl/tal1, hereafter referred to as scl. The gene encodes a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor, which was initially discovered at the sites of chromosomal translocations in leukemic T cells (for a review, see Begley and Green7 ). Gene ablation studies in the mouse have revealed an essential role for scl in hematopoiesis. Scl-/- mouse embryos die at embryonic day 9.5 (E9.5) due to a complete absence of primitive blood cells.8,9 Subsequent studies in chimeras revealed that scl-/- ES cells were also unable to contribute to definitive hematopoiesis.10,11 Using conditional knockouts, scl requirement has been placed upstream of the HSC12,13 ; however, its epistatic relationships with other transcription factors required for programming of HSCs have yet to be determined.

A role for scl in formation of the hemangioblast was suggested by the observation that ectopic expression in zebrafish embryos can direct the differentiation of mesodermal precursors toward endothelial as well as hematopoietic cell fates at the expense of other tissues.14,15 Similarly, enforced scl expression in the zebrafish cloche mutant partially rescued both blood and endothelial gene expression.16 In vitro studies of differentiating mouse ES cells have also implicated scl in specification of both blood and endothelium. Cells doubly sorted for flk1 and scl expression were enriched for BL-CFCs, and BL-CFCs were unable to form in the absence of scl.17-20 Furthermore, ubiquitous scl expression increased the number of flk1+ cells, and scl targeted to the flk1 locus significantly increased the number of blast colonies formed both in the presence and absence of flk1.18,21 Nevertheless, studies to date of the scl null mouse have only indicated a late role in vascular development.8,22,23

In order to examine the consequences of lost scl function in developing embryos in more detail, we used antisense morpholino technology to knockdown expression in zebrafish, successfully recapitulating the defects of the scl-/- mouse with respect to the loss of primitive hematopoiesis. Furthermore, unlike mice, the embryos survive this loss long enough for the absence of emerging HSCs to be evident. Because we can identify the precursors to the blood and endothelial lineages and closely monitor their development, we can determine where in the hierarchy of genetic regulation Scl is required. We present evidence that the crucial erythroid, myeloid, and stem cell genes, gata1, pu.1, and runx1, may be direct targets for Scl. In addition, in contrast to reports in mice, our data reveal serious defects in endothelial development in Scl-depleted embryos, culminating in failure to form a DA. Thus, scl plays a crucial role in the development of the hemangioblast in vivo. Since HSCs have been found to emerge only in association with arteries and not veins, our data suggest that scl is essential for the development of hemogenic endothelium in vivo.

Materials and methods

Morpholinos

Antisense morpholinos (MOs) were obtained from GeneTools (Philomath, OR) with sequences scl atgMO 5′-TTCAGTTTTTCCATCATCCTTCGGC-3′ and scl spliceMO 5′-AATGCTCTTACCATCGTTGATTTCA-3′. Ten μg/μL stock solutions in dH2O were prepared, and 1 ng to 10 ng amounts injected into 1 to 16 cell-stage embryos at the yolk/blastomere boundary. Quantities of MOs injected were titrated to appropriate effective nontoxic levels (ie, 5 ng scl atgMO and 6.5 ng scl spliceMO).

RT-PCR analysis

Reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis to determine efficacy of MO splicing inhibition was carried out with primers 5′-CCTAGCAATCGAGTCAAGCG-3′ and 5′-AAGCTCTCTGGGCTGGCG-3′. Ef1α mRNA was amplified in the same reactions as a loading control, with primers 5′-CACCCTGGGAGTGAAACAG-3′ and 5′-ACTTGCAGGCGATGTGAGC-3′. cDNA template was produced from mRNA isolated from 22 hours postfertilization (hpf) wild type (wt) and 6.5 ng scl spliceMO–injected embryos. PCR products were analyzed on agarose gel, then isolated and cloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega, Southampton, United Kingdom) for sequencing.

mRNA for injection

Zebrafish scl and murine myoD mRNAs for rescue experiments were generated as previously described.15 Scl:green fluorescent protein (GFP) mRNA was transcribed from an scl:GFP fusion construct, pCSzfscl-GFP2GW, generated by recombining an scl entry clone, pEN-zfscl, and GFP destination vector, pCSGFP2GW. The first was created by amplification of an attB-flanked zebrafish scl sequence, including the scl atgMO target sequence, from pFC614 with primers 5′-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTGCCGAAGGATGATGGAAAAAC-3′ and 5′-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTACCGCTGGGCATTTCCGTC-3′, which was recombined with pDONR221 (Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom). The GFP Gateway destination vector was created by introducing Gateway Cassette A (Invitrogen) in frame and immediately upstream of the GFP coding sequence of pCSGFP2.14 Scl:GFP mRNA was then transcribed from linearized template using mMessagemMachine (Ambion, Huntingdon, United Kingdom). Quantities of mRNA were injected in 0.5 nL into one blastomere at the 1- to 4-cell stage.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization

Breeding zebrafish were maintained and embryos were raised and staged according to Westerfield.24 Whole-mount in situ hybridization on zebrafish embryos was carried out as previously described.25 Antisense RNAs for in situ hybridization were transcribed from linearized templates using Promega's T3, T7, and SP6 RNA polymerases in the presence of digoxigenin (DIG)–labeled nucleotides (Roche, Welwyn Garden City, United Kingdom). DIG antibody-alkaline phosphatase conjugate was detected using BM-Purple (Roche) or Fast Red (Sigma, Poole, United Kingdom).

Photography

Images of live embryos and fixed embryos following in situ hybridization were captured using a Nikon SMZ 1500 dissecting microscope (1 × HR Plan Apo objective, numerical aperture 0.13) with a Nikon DXM1200 digital camera driven by Nikon Act-1 version 2.12 software (Nikon UK, Kingston upon Thames, United Kingdom). Images of GFP fluorescent embryos were captured using a Leica MZ FLIII fluorescence stereomicroscope (1 × Plan objective, numerical aperture 0.125; Leica Microsystems, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom) with a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, Welwyn Garden City, United Kingdom) driven by Simple PCI version 5.1.0.0110 software (Compix, Cranberry, PA). Image manipulation was carried out using Adobe Photoshop CS version 8.0 software (Adobe, San Jose, CA).

Results

In zebrafish, primitive hematopoiesis occurs in 2 separate intraembryonic locations. Primitive erythrocytes form in close association with the developing major trunk vessels in the intermediate cell mass (ICM) of the 1-day-old embryo, which derives from the posterior lateral plate mesoderm (PLM) of the postgastrula embryo.26 An early wave of myeloid cells arises, at around the same time, from the anterior lateral plate mesoderm (ALM), which also produces the ECs of the head vasculature.27,28 In both cases, early expression of hematopoietic and endothelial genes overlaps, supporting the existence of a hemangioblast.14,29,30

Primitive erythrocytes begin to leave the ICM and enter circulation from about 24 hpf, soon after the heart first starts to beat. As this happens, a row of single cells associated with the DA becomes evident, clearly identified by the expression of runx1, shown in the mouse to be critical for definitive hematopoiesis.31-34 Comparisons with other species suggest that these cells are anatomically and temporally equivalent to the clusters of HSCs that associate with the ventral wall of the DA. Consistent with this, Runx1-depletion in zebrafish results in the loss of c-myb and ikaros, which are normally coexpressed in these cells,30,35 and a later concomitant loss of the first definitive lineage derivatives in the thymus.61 At 24 hpf, these runx1+ HSCs constitute a ventral subset of the flk1+ DA cells,61 which suggests a common origin with DA precursors in the PLM.26

Scl expression is inhibited by morpholino injection

To knockdown scl expression in zebrafish, we designed 2 antisense MOs. The first MO was designed to target the scl atg and inhibit translation (Figure 1A). To test its effectiveness in the absence of an antibody against endogenous zebrafish Scl protein, we examined whether, in an embryo, it could down-regulate translation of an atgMO-sensitive mRNA encoding a GFP-tagged Scl protein. Coinjection of the atgMO severely reduced the fluorescence detected in scl:GFP mRNA–injected embryos (Figure 1B), showing that the atgMO was active. Morphant embryos displayed specific effects on blood gene expression at early stages of development (discussed later) but as development proceeded they exhibited increasingly severe nonspecific defects, including widespread necrosis and shortening of the axis, which prevented analysis of Scl-depletion in older embryos (Figure 1E).

Scl expression is knocked down by MO injection. (A) Genomic structure of the scl gene. Exons (ex) depicted as boxes, intron sizes not to scale. Atg and spliceMO binding sites and primers for RT-PCR analysis in panel C are shown (red lines and black arrows). The major splice variant obtained after spliceMO injection is indicated by the red line. (B) AtgMO injection blocked translation of a coinjected scl:GFP fusion mRNA that included the MO target sequence. GFP fluorescence was examined at germ ring stage (5.7 hpf) and was found to be strongly reduced in the presence of the atgMO (11 × magnification; views are animal [a] and lateral [l] as indicated). (C) RT-PCR analysis revealed formation of an alternative splice product following spliceMO injection (426 bp, upper red arrow), in addition to residual wt product (401 bp, lower red arrow). (D) DNA sequencing of the alternative splice product revealed the use of a cryptic splice donor 25 bp into the intron (A). These 25 bases (shown in red) caused a frameshift which, when translated, would give rise to a truncated Scl lacking the bHLH. (E) Live 24-hpf embryos (15 × original magnification); lateral views; anterior, left. While spliceMO-injected embryos exhibit normal overall morphology, atgMO-injected embryos displayed severe nonspecific defects by 24 hpf.

Scl expression is knocked down by MO injection. (A) Genomic structure of the scl gene. Exons (ex) depicted as boxes, intron sizes not to scale. Atg and spliceMO binding sites and primers for RT-PCR analysis in panel C are shown (red lines and black arrows). The major splice variant obtained after spliceMO injection is indicated by the red line. (B) AtgMO injection blocked translation of a coinjected scl:GFP fusion mRNA that included the MO target sequence. GFP fluorescence was examined at germ ring stage (5.7 hpf) and was found to be strongly reduced in the presence of the atgMO (11 × magnification; views are animal [a] and lateral [l] as indicated). (C) RT-PCR analysis revealed formation of an alternative splice product following spliceMO injection (426 bp, upper red arrow), in addition to residual wt product (401 bp, lower red arrow). (D) DNA sequencing of the alternative splice product revealed the use of a cryptic splice donor 25 bp into the intron (A). These 25 bases (shown in red) caused a frameshift which, when translated, would give rise to a truncated Scl lacking the bHLH. (E) Live 24-hpf embryos (15 × original magnification); lateral views; anterior, left. While spliceMO-injected embryos exhibit normal overall morphology, atgMO-injected embryos displayed severe nonspecific defects by 24 hpf.

We therefore designed a second MO, using a splice-blocking approach,36 spanning the splice donor sequence of exon 3, upstream of the essential bHLH domain (for a review, see Lecuyer and Hoang37 ) (Figure 1A). To show that the spliceMO interfered with normal scl pre-mRNA splicing, RT-PCR analysis of spliceMO-injected embryos was carried out, revealing a severe reduction in the amount of normal splice product (Figure 1C, lower red arrow) and instead the formation of an aberrantly spliced RNA (Figure 1C, upper red arrow). Sequencing showed inclusion of 25 nucleotides of intron 3, due to use of a downstream cryptic splice donor, which caused a frameshift resulting in translation of a truncated protein lacking the bHLH domain (Figure 1D). Thus, as seen for exogenous Scl:GFP expression with the atgMO, endogenous Scl expression was significantly knocked down with the spliceMO. Importantly though, spliceMO-injected embryos developed without the extensive nonspecific defects observed following injection of the atgMO (Figure 1E), and survived for several days. We therefore present the data for the spliceMO but, with respect to the early expression of all the genes studied, the effects were the same with the atgMO (see the next section).

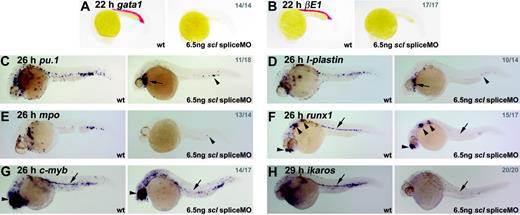

Scl-depleted zebrafish embryos fail to develop primitive or definitive blood, phenocopying the scl knockout mouse

From 24 hpf onwards, although the heart began to beat normally in scl spliceMO-injected embryos, no blood was observed, either in the circulation or accumulated elsewhere. Over time, in the absence of blood circulation, embryos developed pericardial edema but survived for at least 4 days. Expression of gata1, beta embryonic globin 1 (βE1) and aminolevulinate synthase 2 (alas2), which, at this stage, is found in the primitive erythroid lineage, was lost entirely (Figure 2A-B, data not shown).38-40 Similarly, expression of pu.1, l-plastin, and mpo, which are expressed in the primitive myeloid lineage (predominantly macrophages), was significantly down-regulated in 26-hpf embryos (Figure 2C-E; see Crowhurst et al27 and references therein). Some expressing cells remained under the heart and in the posterior ICM (Figure 2C–E, arrows and arrowheads). Thus, Scl-depletion in zebrafish recapitulates the phenotype of the scl-/- mouse with respect to the primitive blood.8,9

Hematopoietic gene expression is lost or severely reduced in Scl-depleted embryos. (A-H) Whole-mount embryos (15 × original magnification); lateral views; anterior, left; numbers of embryos represented in gray. (A, B) Erythroid gata1 and βE1 expression was lost in all morphants at 22 hpf. (C-E) In 26-hpf morphants, expression of primitive myeloid genes, pu.1, l-plastin, and mpo, was severely reduced. Remaining cells were restricted to the heart region (arrows) and posterior ICM (arrowheads). (F-H) HSCs were lost in Scl-depleted embryos. Runx1 and c-myb expression at 26 hpf associated with the DA was lost in scl morphants (F, G, arrows). In both cases, nonhematopoietic expression was unaffected (arrowheads).30,35 Ikaros expression in primitive blood and HSCs was lost in 29-hpf morphants (C, arrow). In each case, any remaining expressing cells were restricted to the posterior ICM.

Hematopoietic gene expression is lost or severely reduced in Scl-depleted embryos. (A-H) Whole-mount embryos (15 × original magnification); lateral views; anterior, left; numbers of embryos represented in gray. (A, B) Erythroid gata1 and βE1 expression was lost in all morphants at 22 hpf. (C-E) In 26-hpf morphants, expression of primitive myeloid genes, pu.1, l-plastin, and mpo, was severely reduced. Remaining cells were restricted to the heart region (arrows) and posterior ICM (arrowheads). (F-H) HSCs were lost in Scl-depleted embryos. Runx1 and c-myb expression at 26 hpf associated with the DA was lost in scl morphants (F, G, arrows). In both cases, nonhematopoietic expression was unaffected (arrowheads).30,35 Ikaros expression in primitive blood and HSCs was lost in 29-hpf morphants (C, arrow). In each case, any remaining expressing cells were restricted to the posterior ICM.

Expression of runx1 and c-myb at 26 hpf in HSCs was almost entirely lost in morphant embryos (Figure 2F-G, arrows), while expression of ikaros at 29 hpf was lost in both circulating primitive erythrocytes and HSCs (Figure 2H, arrow). The very few cells that continued to express any of these 3 markers were confined to the posterior-most portion of the ICM. Thus, the absence of DA-associated HSCs was clearly evident in Scl-depleted zebrafish embryos, an observation not possible in knockout mice due to early lethality.

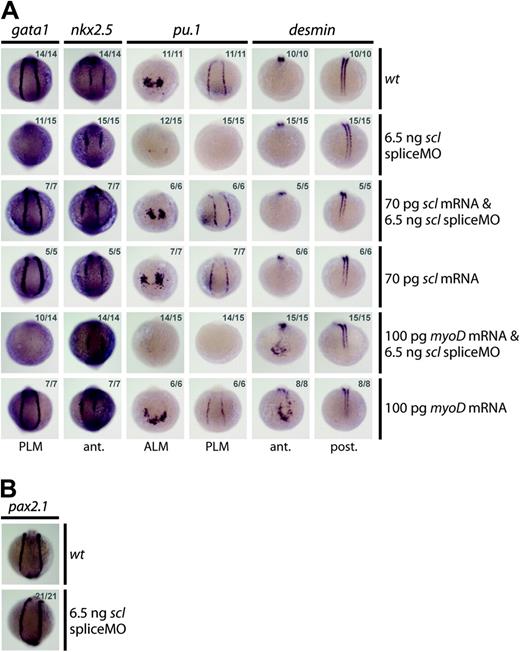

Several lines of evidence indicated that injection of the scl spliceMO generated a highly specific knockdown phenotype. First, the MO substantially reduced scl expression without negative effects on the overall morphology of the embryos (Figure 1E). Scl-negative tissues such as the runx1 and c-myb–expressing nonhematopoietic lineages, the nkx2.5+ cardiac mesoderm, and the pax2.1+ pronephric duct progenitors were completely unaltered (Figure 2F-G and Figure 3A-B). Second, 2 independent MOs gave the same blood defects. Although the atgMO generated extensive nonspecific defects on injection (Figure 1E), it nevertheless revealed the same defects in hematopoietic gene expression at early stages of development (eg, loss of gata1 and pu.1 expression at 10 somites [14 hpf]; data not shown). Third, MO-induced hematopoietic defects were rescued by coinjection of a correctly spliced scl mRNA: expression of gata1 in the PLM, and of pu.1 in the ALM and the PLM, was restored in 10-somite (14 hpf) embryos (Figure 3A). Coinjection of the scl spliceMO with an alternative member of the bHLH family, the murine myogenic transcription factor, myoD, did not restore gata1 or pu.1 expression, confirming specificity of the rescue (Figure 3A). The myoD RNA was able to ectopically induce the expression of one of its downstream targets, desmin (des), in the head at 10 somites (14 hpf), as previously described,15 thereby proving its activity (Figure 3A). In summary, our data show that the morphant phenotype generated was highly specific and that the defects observed were tightly restricted to the regions where scl is expressed.

SpliceMO-mediated Scl knockdown is highly specific. (A, B) Wholemount 10-somite (14 hpf) embryos (10.5 × magnification); posterior/anterior views as indicated; dorsal, top; numbers of embryos represented in gray. (A) Coinjection with correctly spliced scl mRNA but not myoD mRNA, together with the scl spliceMO, rescued early gata1 and pu.1 expression in the PLM and the PLM and ALM, respectively. Nkx2.5 in the heart (A) and Pax2.1 in the pronephric duct mesoderm (B) were unaffected by these injections. Ectopic anterior expression of des at 10 somites (14 hpf) confirms that myoD mRNA was active.

SpliceMO-mediated Scl knockdown is highly specific. (A, B) Wholemount 10-somite (14 hpf) embryos (10.5 × magnification); posterior/anterior views as indicated; dorsal, top; numbers of embryos represented in gray. (A) Coinjection with correctly spliced scl mRNA but not myoD mRNA, together with the scl spliceMO, rescued early gata1 and pu.1 expression in the PLM and the PLM and ALM, respectively. Nkx2.5 in the heart (A) and Pax2.1 in the pronephric duct mesoderm (B) were unaffected by these injections. Ectopic anterior expression of des at 10 somites (14 hpf) confirms that myoD mRNA was active.

The position of scl in the regulatory cascade of hematopoietic genes in the PLM (primitive erythroid and HSCs)

To determine precisely where in the regulatory networks leading to blood formation scl acts, we have attempted to trace the earliest defects in gene expression in our morphant embryos. An advantage of the fish system is that the cells giving rise to blood and endothelium can be observed at approximately 20- to 30-minute intervals as individual somites are added (Figure 4I). We can therefore identify the developmental stage when the loss of scl first affects the genetic program of these cells and also determine whether scl is needed for the initiation or maintenance of the expression of individual genes.

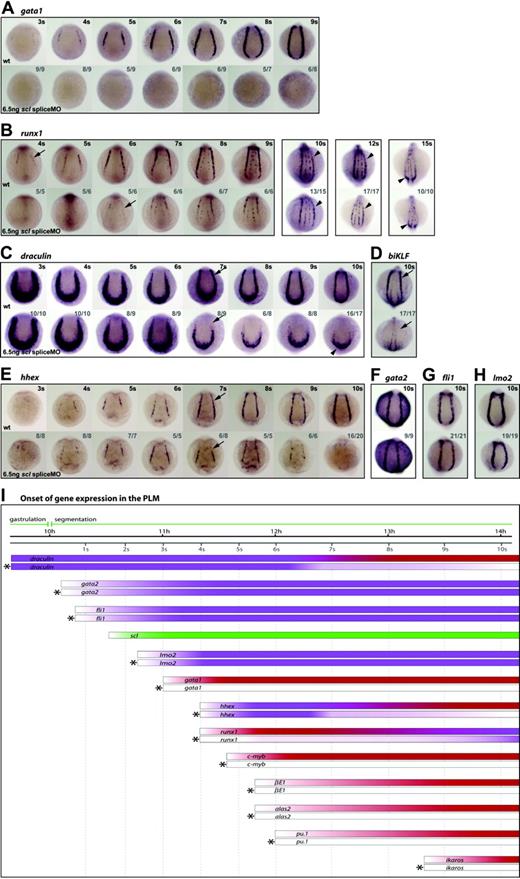

Scl is a critical regulator of PLM development. (A-H) Whole-mount embryos (12 × magnification); posterior views; dorsal, top; numbers of embryos represented in gray. Gata1 expression was never observed in the PLM of morphant embryos (A). Runx1 was at first dependent on Scl, initiated weakly in the PLM of morphants at 6 somites (12 hpf) (B, arrow), and by the 10- to 12-somite stage (14 hpf-15 hpf) appeared almost as robust as wt (B, arrowheads). dra was initially expressed normally in morphants, but appeared reduced from 7 somites (12.5 hpf) (C, arrows). The posterior-most region of dra expression was unaffected (C, arrowhead). biKLF expression was lost in morphants by 10 somites (14 hpf) (D). Hhex expression initiated as normal, appeared reduced at 7 somites (12.5 hpf) (E, arrows) and was lost by 10 somites (14 hpf) (E). Gata2, fli1, and lmo2 expression in the PLM was unaffected in 10-somite (14 hpf) morphants (F-H). (I) Data from in situ analyses are summarized schematically. Bars represent the changing expression of genes over time. Bars marked by asterisks represent gene expression in morphants. Purple, Scl-independence; red, Scl-dependence; green, scl expression.

Scl is a critical regulator of PLM development. (A-H) Whole-mount embryos (12 × magnification); posterior views; dorsal, top; numbers of embryos represented in gray. Gata1 expression was never observed in the PLM of morphant embryos (A). Runx1 was at first dependent on Scl, initiated weakly in the PLM of morphants at 6 somites (12 hpf) (B, arrow), and by the 10- to 12-somite stage (14 hpf-15 hpf) appeared almost as robust as wt (B, arrowheads). dra was initially expressed normally in morphants, but appeared reduced from 7 somites (12.5 hpf) (C, arrows). The posterior-most region of dra expression was unaffected (C, arrowhead). biKLF expression was lost in morphants by 10 somites (14 hpf) (D). Hhex expression initiated as normal, appeared reduced at 7 somites (12.5 hpf) (E, arrows) and was lost by 10 somites (14 hpf) (E). Gata2, fli1, and lmo2 expression in the PLM was unaffected in 10-somite (14 hpf) morphants (F-H). (I) Data from in situ analyses are summarized schematically. Bars represent the changing expression of genes over time. Bars marked by asterisks represent gene expression in morphants. Purple, Scl-independence; red, Scl-dependence; green, scl expression.

Scl expression in the PLM initiates between 1 to 2 somites (∼10.5 hpf), shortly after gastrulation, and is an early marker for these cells14 (Figure 4I). With respect to the consequences of Scl-depletion, we identified 4 categories of hematopoietic gene in this region.

Dependent: for initiation and maintenance. Expression of terminal differentiation genes, βE1 and alas2, and regulators, gata1, pu.1, c-myb and ikaros, was never observed in morphants at early stages of PLM development (Figure 2A-B, Figure 4A,I, and data not shown). Scl is therefore essential, either directly or indirectly, for the initiation of expression of these genes.

Dependent: for timing of initiation.Runx1 expression in morphants started at 6 somites (12 hpf) instead of 4 somites (11.3 hpf), but increased until at 10 to 12 somites (14 hpf-15 hpf) it appeared similar to wt (Figure 4B,I). These data suggest that while scl is required for normal timing of initiation of runx1 expression in the PLM, its expression is subsequently maintained and strengthened by other factors, eventually becoming almost Scl-independent.

Dependent: for maintenance. Genes in this category include regulators, such as biKLF and draculin (dra), initially expressed more broadly in lateral plate mesoderm before the onset of scl expression, and later restricted to blood precursors.41,42 Control of early expression of these genes must be Scl-independent, but expression of both genes was lost in most of the PLM by 10 somites (14 hpf) in MO-injected embryos (Figure 4C-D,I). Reduction in dra expression (ie, Scl dependence) was evident from the 7-somites (12.5 hpf) stage (Figure 4C, arrows; Figure 4I), but residual expression remained in the PLM around the tailbud (Figure 4C, arrowhead). This region of the PLM is scl-negative at this time (data not shown) and therefore dra expression would not be expected to be Scl-dependent. This category also includes hhex, normally expressed in the PLM from around 4 somites (11.3 hpf). Gain-of-function experiments have shown that scl can induce ectopic hhex expression.43 Nevertheless, in scl morphants, hhex expression initiated normally and persisted until 6 somites (12 hpf; Figure 4E,I). After this time, however, levels of expression became progressively reduced, and at 10 somites (14 hpf) were lost entirely. This indicates that while initiation of hhex expression is Scl-independent, like dra, maintenance of hhex in the PLM from around 7 somites (12.5 hpf) onwards requires functional Scl.

Independent. Genes in this category include gata2 and fli1, which appear in the PLM before scl and are thought to be its activators, and lmo2, which appears in the PLM soon after scl and acts in a complex with it.15,30,38,44,45 In scl morphants, the expression of these genes was unaffected at 10 somites (14 hpf) or earlier (Figure 4F-I, data not shown). Thus, a precursor population, expressing hemangioblast genes, was still present in the PLM, although it was unable to elaborate the blood program in the absence of Scl.

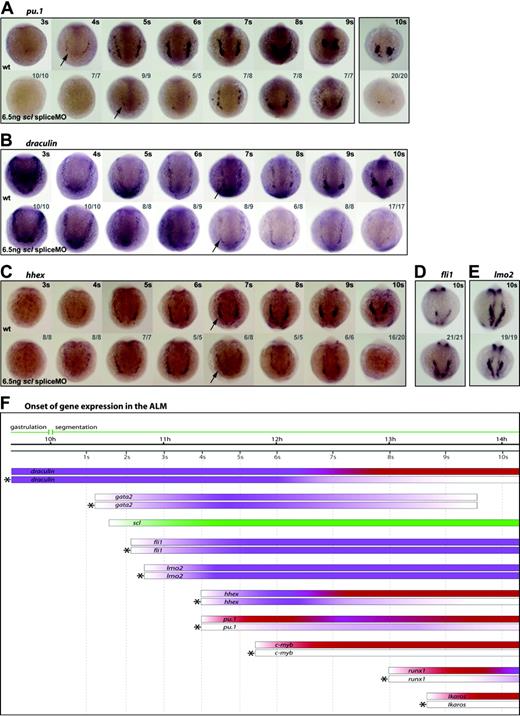

The position of scl in the regulatory cascade of hematopoietic genes in the ALM (primitive myeloid)

As in the PLM, scl is expressed in the ALM from 1 to 2 somites (∼10.5 hpf)14 (Figure 5F). The consequences of Scl-depletion for the expression of hematopoietic genes in this region fell into the same 4 categories:

Scl is a critical regulator of early myeloid development. (A-E) Whole-mount embryos (13 × magnification); anterior views; dorsal, top; numbers of embryos represented in gray. Pu.1 expression in the ALM initiated weakly in morphants and 1 somite later than wt (A, arrows), remaining weak until 10 somites (14 hpf) (A). dra was expressed normally in Scl-depleted embryos until 6 somites (12 hpf), then began to appear reduced (B, arrows). Similarly, hhex expression was reduced at 7 somites (12.5 hpf), and was lost by 10 somites (14 hpf) (C, arrows). Fli1 and lmo2 expression in the ALM at 10 somites (14 hpf) was unaffected by Scl-depletion (D, E). (F) Data from such in situ analyses are summarized schematically, as described for Figure 4.

Scl is a critical regulator of early myeloid development. (A-E) Whole-mount embryos (13 × magnification); anterior views; dorsal, top; numbers of embryos represented in gray. Pu.1 expression in the ALM initiated weakly in morphants and 1 somite later than wt (A, arrows), remaining weak until 10 somites (14 hpf) (A). dra was expressed normally in Scl-depleted embryos until 6 somites (12 hpf), then began to appear reduced (B, arrows). Similarly, hhex expression was reduced at 7 somites (12.5 hpf), and was lost by 10 somites (14 hpf) (C, arrows). Fli1 and lmo2 expression in the ALM at 10 somites (14 hpf) was unaffected by Scl-depletion (D, E). (F) Data from such in situ analyses are summarized schematically, as described for Figure 4.

Dependent: for initiation and maintenance. As seen in the PLM, pu.1, c-myb, and ikaros expression was substantially reduced or lost in the ALM of scl morphants (Figure 5A, arrows, Figure 5F, data not shown). Thus, these regulators of myeloid differentiation are dependent, either directly or indirectly, on Scl for their expression.

Dependent: for timing of initiation. Initiation of runx1 expression in the ALM, as in the PLM, was delayed in MO-injected embryos, in this instance from 8 somites (13 hpf) to 10 somites (14 hpf) (Figure 5F, data not shown). Expression persisted, albeit weakly, until at least 15 somites (16.5 hpf), although the few runx1+ cells remaining did not migrate (Figure 5F, data not shown). For this reason it was not clear from the data whether runx1 expression in the ALM recovered as fully as in the PLM. Nevertheless, it is clear that correct initiation of runx1 in the ALM requires Scl.

Dependent: for maintenance. As in the PLM, the broad expression of dra in the ALM region before scl is switched on was, as expected, controlled independently of Scl. However, by 7 somites (12.5 hpf) when dra expression is becoming restricted to the ALM, its expression was substantially reduced in morphants, and was lost by 10 somites (14 hpf) (Figure 5B, arrows, Figure 5F). The same profile of hhex expression seen in the PLM (namely switched on normally at 4 somites [11.3 hpf] but starting to decay at 7 somites [12.5 hpf] and gone by 10 somites [14 hpf]), was seen in the ALM (Figure 5C,F). Thus, as in the PLM, the expression of dra and hhex in the ALM becomes Scl-dependent at 7 somites (12.5 hpf).

Independent. Also as seen in the PLM, expression of fli1 and lmo2 was unaffected in the ALM of MO-injected embryos at 10 somites (14 hpf) and earlier (Figure 5D-F, data not shown). At this time, anterior gata2 expression can only be detected in the ectoderm and is no longer present in the ALM of wt embryos. However, its expression in the ALM at 5 somites (11.6 hpf) was unaffected by Scl-depletion (Figure 5F, data not shown). Thus, as in the PLM, the expression of gata2, fli1, and lmo2 is independent of Scl. Persistence of expression of these early hemangioblast genes indicates that precursor cells were not lost, but that their elaboration of the myeloid program was compromised in the absence of Scl.

We conclude that the regulatory circuitry in the myeloid ALM bears marked similarities to that in the erythroid and HSC PLM with respect to the role of Scl.

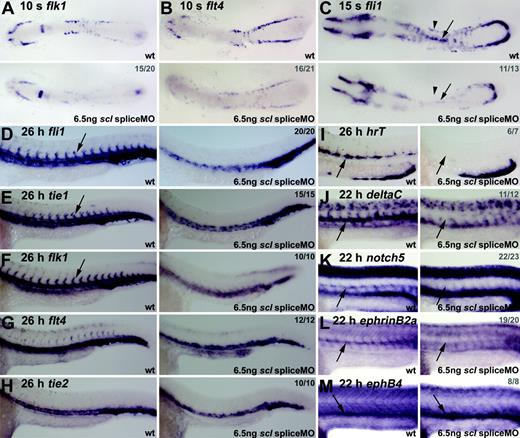

Endothelial gene expression is reduced in Scl-depleted embryos

To study vasculogenesis in Scl-depleted embryos, we analyzed expression of the VEGF receptors, flk1 and flt4.30,46 Both were substantially reduced in scl morphants (both spliceMO- and atgMO-injected embryos) at 10 somites (14 hpf) (Figure 6A-B, data not shown). This loss of expression did not reflect loss of cells as fli1 expression was normal at this stage of development (Figure 4G). As observed with blood markers (Figure 3A), endothelial gene expression could be restored to more normal levels in the lateral plate mesoderm of morphant embryos by coinjection with scl mRNA, although as expected, scl overexpression also caused ectopic endothelial gene expression in the paraxial mesoderm14 (data not shown). Around this time, a subset of these VEGF receptor–expressing angioblasts in the PLM begin to migrate toward the midline producing a line of cells that will form the DA, here shown expressing fli1 at 15 somites (16.5 hpf) (Figure 6C, wt, arrow).46 Posterior cardinal vein (PCV) progenitors remain lateral at this time, and eventually coalesce at the midline, ventral to the DA, as a result of more general morphologic movements. In MO-injected embryos, the distinct line of DA precursor cells at the midline was barely evident (Figure 6C, arrows). In addition, fli1 expression in PCV precursors was severely reduced (Figure 6C, arrowheads). Thus, the expression of 2 VEGF receptors central to the endothelial program, and a key transcription factor, were severely compromised when Scl was depleted, indicating a fundamental requirement for Scl in the initiation and maintenance of that program.

Endothelial development is severely disrupted in Scl-depleted embryos. (A-C) Flat-mount embryos; anterior, left (A-B, 18 × magnification; C, 21 × magnification). (D-H) Whole-mount embryos; lateral view; close-up of trunk/tail region; anterior, left. (I-M) Wholemount embryos (45 × magnification); lateral view; close-up of trunk region; anterior, left. Numbers of embryos represented in gray. At 10 somites (14 hpf), flk1 and flt4 expression in the ALM and PLM was severely reduced in morphant embryos (A, B). At 15 somites (16.5 hpf), fli1 expression was significantly reduced in morphants (C), and the line of DA precursors forming at the midline was not as distinct as in wt (C, arrows). In 26-hpf morphants, fli1 and tie1 expression was severely reduced in the trunk region and lost in ISVs (D, E, arrows). Flk1 expression in the DA was lost, with remaining expression ventrally and laterally (F). At 26 hpf, expression of flt4 and tie2, mainly restricted to the PCV, was not significantly down-regulated in morphant embryos (G, H). (I-M) DA-but not PCV-specific gene expression was lost in Scl-depleted embryos. Expression of artery-specific genes hrT (I), deltaC (J), notch5 (K), and ephrinB2a (L) was entirely lost in morphants. EphB4 expression in the PCV, however, was not depleted (M).

Endothelial development is severely disrupted in Scl-depleted embryos. (A-C) Flat-mount embryos; anterior, left (A-B, 18 × magnification; C, 21 × magnification). (D-H) Whole-mount embryos; lateral view; close-up of trunk/tail region; anterior, left. (I-M) Wholemount embryos (45 × magnification); lateral view; close-up of trunk region; anterior, left. Numbers of embryos represented in gray. At 10 somites (14 hpf), flk1 and flt4 expression in the ALM and PLM was severely reduced in morphant embryos (A, B). At 15 somites (16.5 hpf), fli1 expression was significantly reduced in morphants (C), and the line of DA precursors forming at the midline was not as distinct as in wt (C, arrows). In 26-hpf morphants, fli1 and tie1 expression was severely reduced in the trunk region and lost in ISVs (D, E, arrows). Flk1 expression in the DA was lost, with remaining expression ventrally and laterally (F). At 26 hpf, expression of flt4 and tie2, mainly restricted to the PCV, was not significantly down-regulated in morphant embryos (G, H). (I-M) DA-but not PCV-specific gene expression was lost in Scl-depleted embryos. Expression of artery-specific genes hrT (I), deltaC (J), notch5 (K), and ephrinB2a (L) was entirely lost in morphants. EphB4 expression in the PCV, however, was not depleted (M).

Scl is required for DA formation

In 26-hpf scl morphant embryos, expression of fli1 and the later endothelial marker tie147 in the midline where the 2 axial vessels develop was significantly down-regulated (Figure 6D-E). Most of the remaining expression was located in the position of the PCV rather than the DA. Furthermore, the intersomitic vessels (ISVs) that normally sprout from the DA at this time were not present. These observations suggested that DA development was compromised. In support of this interpretation, the strong expression of flk1 in the DA and ISVs was absent (Figure 6F). In contrast, expression of flt4 and tie2 (tek), which are more restricted to the PCV,47 were not as significantly down-regulated in morphants (Figure 6G-H). Together, the location of panendothelial marker expression, the severe reduction of DA-predominant gene expression, and the relatively normal expression of PCV-predominant markers, suggest that scl is more critical for DA formation than for PCV.

To test this suggestion further, we analyzed the expression of several aorta-specific markers in the morphant embryos. HrT, notch5, deltaC, and ephrinB2a have artery-specific vascular expression patterns and are restricted to the DA at this early stage of zebrafish development.48 All 4 were entirely lost in morphants, whereas expression of the vein-specific marker, ephB4, was intact (Figure 6I-M).48

We therefore conclude that, in zebrafish embryos, scl is required for normal endothelial development and is particularly crucial for the development of the DA.

Discussion

Scl and blood formation

With respect to blood development, we broadly obtain the same phenotype as mouse knockout models, namely loss of both primitive and definitive hematopoiesis. We have been able to show that HSCs, which emerge in association with the floor of the DA, are absent in these embryos, an observation not possible in knockout mice due to early lethality. The ability to closely monitor the precursors of both primitive and definitive blood as they develop in zebrafish embryos has allowed us to define the earliest time at which the depletion of Scl affects the blood program. We show that, at the 10-somite stage, gata2, fli1, and lmo2 are regulated independently of scl but all other blood genes analyzed are dependent, either directly or indirectly. This is equally true of the PLM, which gives rise to the primitive erythroid cells and probably the HSCs, and of the ALM, which gives rise to the primitive myeloid cells.

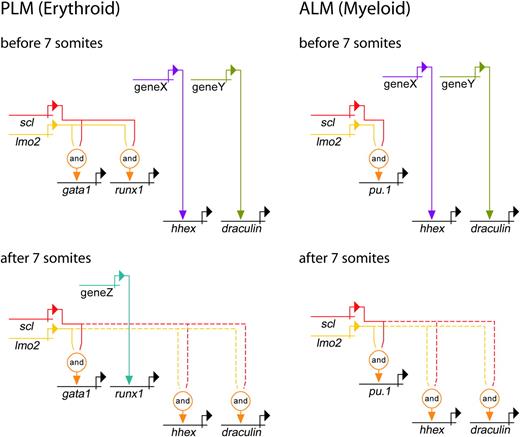

We found that the first sign of perturbation of the network in the PLM was the failure of gata1 activation at 3 to 4 somites, approximately 40 minutes after scl would normally be switched on. This period of time is unlikely to be long enough for the synthesis of intermediates; therefore, our data suggest that Scl activates gata1 directly in embryonic precursors to erythroid cells (Figure 7). Consistent with this suggestion, residual gata1 expression in scl-/- mouse embryos and EBs was very low.10,50,51 Lmo2 and Gata2, activated before gata1 in the PLM, are likely partners for Scl in this activation, although gain-of-function experiments show that this complex is only sufficient to activate gata1 in a subset of embryonic mesoderm.15 Therefore, while our data show that Scl is necessary for induction of normal gata1 expression, and that this is probably a direct relationship, Scl is not sufficient for gata1 activation, and requires other factors, including components of the multiprotein complex, which are expressed in a tissue-restricted pattern. The first sign of any effect on the hematopoietic network in the ALM was the failure of pu.1 initiation at 4 somites, approximately 50 minutes after the scl gene is initially activated. Thus, pu.1 looks like a direct target for Scl, acting with Lmo2 and Gata2, in myeloid precursors (Figure 7). Hhex and dra were expressed normally in the PLM and ALM in an Scl-independent fashion. By 7 somites, however, hhex, dra, and all other hematopoietic gene expression measured in this study had become dependent on Scl, either directly or indirectly (Figure 7). Therefore, in gata1 and pu.1, we have identified likely direct targets for scl at the top of the primitive erythroid and myeloid genetic regulatory cascades. Direct targets for Scl in the maintenance of these programs may also be among the genes studied here.

Genetic regulatory networks controlling early PLM and ALM development. Direct relationships, illustrated by continuous lines, are defined by 3 criteria: (1) target gene expression is affected by perturbation of activator; (2) target gene and activator are coexpressed; (3) target gene promoter/enhancer sequences contain binding sites for activators, or length of time between perturbation of activator and effect on target gene is probably insufficient to allow for synthesis of intermediates. Where criteria 1 and 2 are met but 3 is unknown, the relationship is described as indirect and depicted by a dashed line. Lmo2 does not bind DNA, but is known to be an obligate member of a multiprotein complex containing Scl (represented here by the “and” function).15,37 PLM (Erythroid): A gata1 enhancer contains binding sites for the multiprotein complex containing Scl and Lmo2.49 Our data show that initiation of gata1 expression is Scl-dependent. Initially, runx1 expression is dependent on Scl, whereas hhex and dra are Scl-independent. After 7 somites (12.5 hpf), hhex and dra become dependent on Scl, whereas runx1 expression gradually becomes Scl-independent. ALM (Myeloid): Pu.1 expression is initially dependent on Scl, whereas hhex and dra are independent. After 7 somites (12.5 hpf), hhex and dra become Scl-dependent. Unknown activators of Scl-independent genes are depicted as genes X, Y, and Z. It is possible that X and Y represent the same gene due to similarities in timing of involvement.

Genetic regulatory networks controlling early PLM and ALM development. Direct relationships, illustrated by continuous lines, are defined by 3 criteria: (1) target gene expression is affected by perturbation of activator; (2) target gene and activator are coexpressed; (3) target gene promoter/enhancer sequences contain binding sites for activators, or length of time between perturbation of activator and effect on target gene is probably insufficient to allow for synthesis of intermediates. Where criteria 1 and 2 are met but 3 is unknown, the relationship is described as indirect and depicted by a dashed line. Lmo2 does not bind DNA, but is known to be an obligate member of a multiprotein complex containing Scl (represented here by the “and” function).15,37 PLM (Erythroid): A gata1 enhancer contains binding sites for the multiprotein complex containing Scl and Lmo2.49 Our data show that initiation of gata1 expression is Scl-dependent. Initially, runx1 expression is dependent on Scl, whereas hhex and dra are Scl-independent. After 7 somites (12.5 hpf), hhex and dra become dependent on Scl, whereas runx1 expression gradually becomes Scl-independent. ALM (Myeloid): Pu.1 expression is initially dependent on Scl, whereas hhex and dra are independent. After 7 somites (12.5 hpf), hhex and dra become Scl-dependent. Unknown activators of Scl-independent genes are depicted as genes X, Y, and Z. It is possible that X and Y represent the same gene due to similarities in timing of involvement.

Runx1 is a key regulator of HSC emergence in the developing embryo but very little is currently known about control of its expression. Here we show that early runx1 expression, in the cells giving rise to primitive erythroid and myeloid and HSC lineages, is initially dependent on Scl. Expression of runx1 in the PLM follows that of scl by less than 1 hour, making it another possible direct target (Figure 7). To our knowledge this is the first evidence suggesting that Scl might be a regulator of runx1. However, in both mouse and fish, loss of runx1 expression has no major effect on primitive erythroid development.31,61 It is therefore not clear what role runx1, and its regulation by Scl, plays in the PLM at this time. In the ALM, runx1 expression initiates 2.5 hours after that of scl, making it more likely to be an indirect target in this tissue. Over time, an Scl-independent pathway is able to compensate for the absence of Scl, and runx1 expression levels in both the ALM and PLM increase (Figure 7). Runx1 expression is, however, absent later when it would normally be on in HSCs. Although the mechanism of this loss is unclear, since depletion of Scl leads to loss of the DA (described in the next section), and HSC emergence occurs in association with the DA, the loss of runx1+ HSCs in scl morphants is likely to be related to the loss of the DA.

Role of Scl in vasculogenesis and angiogenesis

While Scl-depleted mouse embryos displayed late angiogenic remodeling defects,8,22,23 zebrafish scl morphants exhibited much earlier vasculogenic defects. The most obvious difference in molecular terms is the loss of flk1 expression in Scl-depleted zebrafish embryos, which is in stark contrast to the apparently normal expression of mouse flk1 in scl-/- E9.5 YS and EBs.22,23 While flk1 expression precedes scl in the mouse,17,52 and scl expression was lost in flk1-/- mice,18 flk1 expression in zebrafish only starts after scl expression,14,16,46 which is independent of Flk1.53 In the mouse, Flk1 and VEGF signaling have essential early roles in mesodermal cell migration and blood and endothelial differentiation, as well as later functions in normal and tumor angiogenesis. Thus, mutations in the VEGF pathway in the mouse (flk1-/-, VEGF+/-, and plcg1-/-) caused severe early defects. Extra-embryonic mesoderm accumulated in the allantois, scl expression and primitive erythropoiesis were lost, and vasculogenesis was severely affected.54-57 By contrast, in zebrafish, flk1 and plcg1 mutants, VEGF morphants, and embryos treated with a VEGF receptor inhibitor displayed a much later phenotype53,58,61 scl expression, primitive erythropoiesis, and vasculogenesis were normal, and only DA specification and angiogenic sprouting were affected. Thus, although we cannot yet rule out the existence of a Flk1 paralogue upstream of scl, current evidence argues that the early role of Flk1 and VEGF signaling in scl induction, primitive hematopoiesis, and vasculogenesis is not conserved in zebrafish.

The absence of an early role for VEGF signaling in zebrafish has consequences. First, scl expression becomes Flk1-independent. Interestingly, even in the mouse, the dependence of scl expression on VEGF might not be absolute, since flk1-/- cells can undergo erythroid differentiation in the presence of serum in vitro,59,60 suggesting that other signals can replace VEGF in erythroid differentiation and in scl activation. Second, Scl takes on an early essential role in vasculogenesis. Such a role, though not essential in the presence of functional VEGF signaling, may also exist in the mouse. Scl expression under the flk1 promoter partially rescued blood and endothelial cell differentiation in a flk1-/- background and induced BL-CFCs in flk1-/- ES cells.18 This suggests that even in the mouse, once VEGF signaling has allowed scl expression, Scl acts in parallel with VEGF signaling during blood and endothelial differentiation. Their roles are, however, not completely overlapping. Scl cannot fully rescue blood and endothelial development in a flk1-/- embryo, and the presence of a functional VEGF pathway cannot prevent the reduction of platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM) expression, the ISV defect or the angiogenic remodeling defects observed in the scl-/- mouse embryo.

Based on data generated by us and others in zebrafish,14-16 we postulate a role for Scl upstream of flk1. Evidence for such a role in the mouse comes from the importance of Scl binding to an flk1 endothelial enhancer for higher level expression of a reporter transgene at E11 and E12, and also from expression of scl under flk1 regulatory elements increasing expression of a flk1-lacZ transgene in a flk1-/- background.18

Requirement for Scl in the formation of hemogenic as opposed to nonhemogenic endothelium

The DA was more affected than the PCV by the loss of scl expression. DA ISVs were missing, arterial gene expression was lost at 26 hpf, and even the expression of panendothelial markers was reduced in scl morphant zebrafish embryos. In addition, aorta-associated HSCs did not form in Scl-depleted zebrafish embryos. VEGF signaling is known to be required for DA specification and HSC formation in a cascade of signaling molecules downstream of Hedgehog and upstream of Notch.58,61 Thus, loss of VEGF receptor expression, as observed for flk1 in Scl-depleted embryos, would be sufficient to cause these defects, an idea consistent with the cell-autonomous Flk1 requirement for mouse definitive hematopoiesis. The ECs of the PCV were less affected by the loss of Scl, as the expression of several endothelial and vein-specific markers was almost normal in the position of the PCV. Even the normally comparatively weak expression of flk1 in the PCV ECs was present in scl morphants. This is consistent with observations in mice and differentiating ES cells that ECs can still be obtained in the absence of Scl function. Since definitive hematopoiesis is associated with arteries and not veins, this argues that Scl is required specifically for the proper formation of hemogenic rather than nonhemogenic endothelium.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, January 11, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3547.

Supported by the Medical Research Council (MRC) and a Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) studentship (L.J.P.).

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears in the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We are grateful to A. Ciau-Uitz, C. Fernandez, B. Gottgens, C. Porcher, A. Rodaway, and M. Walmsley for critical reading of the manuscript, and to L. Mitchell for technical assistance. We would also like to thank C. Amemiya, J. Campos-Ortega, Y. Cheng, K. Crosier, I. Dawid, M. Fishman, K. Griffin, M. Hammerschmidt, P. Ingham, G. Lieschke, K. Peters, D. Stainier, B. Thisse, S. Wilson, and L. Zon for probes.

![Figure 1. Scl expression is knocked down by MO injection. (A) Genomic structure of the scl gene. Exons (ex) depicted as boxes, intron sizes not to scale. Atg and spliceMO binding sites and primers for RT-PCR analysis in panel C are shown (red lines and black arrows). The major splice variant obtained after spliceMO injection is indicated by the red line. (B) AtgMO injection blocked translation of a coinjected scl:GFP fusion mRNA that included the MO target sequence. GFP fluorescence was examined at germ ring stage (5.7 hpf) and was found to be strongly reduced in the presence of the atgMO (11 × magnification; views are animal [a] and lateral [l] as indicated). (C) RT-PCR analysis revealed formation of an alternative splice product following spliceMO injection (426 bp, upper red arrow), in addition to residual wt product (401 bp, lower red arrow). (D) DNA sequencing of the alternative splice product revealed the use of a cryptic splice donor 25 bp into the intron (A). These 25 bases (shown in red) caused a frameshift which, when translated, would give rise to a truncated Scl lacking the bHLH. (E) Live 24-hpf embryos (15 × original magnification); lateral views; anterior, left. While spliceMO-injected embryos exhibit normal overall morphology, atgMO-injected embryos displayed severe nonspecific defects by 24 hpf.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/105/9/10.1182_blood-2004-09-3547/6/m_zh80090577850001.jpeg?Expires=1769107461&Signature=coSob2C5Sih9OEzojJEOK1JMZZqj~xhg0c0WHkFoT5qxsN2Hk4GKetXwF0ijVqvZVBXztbzmB~tA-TcEHUtb8OVyTtgeWsbaoQsdwL1p-fY9fw0SLN3L3h7bYvAscafIMk51knKKh3dRMdPnjLrCNzMaG~Wrc7RLb1~rmxOTcRge4yoY5F0G-XfEKKGHYDSGlnNyJiUTEnBAYxvuKK9n4azKz2Ztyr1oB3Y6gLkVdHoUGVY3jSKWjguv7qfH3sngHYE2VxC83eZXIGsJzbesbeWq1Rr6ic7lyhGSXSQbWOn7YwA-OIQsbNU~~jc98WpAqJDHx6uxYUsShU0PPFXIxw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal