Transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) plays a central role in the pathogenesis of classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL). In anaplastic large-cell lymphomas (ALCLs), which share molecular lesions with cHL, the NF-κB system has not been equivalently investigated. Here we describe constitutive NF-κB p50 homodimer [(p50)2] activity in ALCL cells in the absence of constitutive activation of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex. Furthermore, (p50)2 contributes to the NF-κB activity in Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells. Bcl-3, which is an inducer of nuclear (p50)2 and is associated with (p50)2 in ALCL and HRS cell lines, is abundantly expressed in ALCL and HRS cells. Notably, a selective overexpression of Bcl-3 target genes is found in ALCL cells. By immunohistochemical screening of 288 lymphoma cases, a strong Bcl-3 expression in cHL and in peripheral T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (T-NHL) including ALCL was found. In 3 of 6 HRS cell lines and 25% of primary ALCL, a copy number increase of the BCL3 gene locus was identified. Together, these data suggest that elevated Bcl-3 expression has an important function in cHL and peripheral T-NHL, in particular ALCL.

Introduction

Transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) plays a key role in the regulation of immune and inflammatory responses, functions as a potent inhibitor of apoptosis, and is involved in malignant transformation of different cell types (for recent reviews see Rayet and Gelinas,1 Karin and Ben-Neriah,2 and Bonizzi and Karin3 ). Depending on the stimulus, the duration of stimulation, and the cellular context, the NF-κB family members p50, p52, p65 (RelA), RelB, and c-Rel form different homo- or heterodimers. p50 and p52 are derived from precursor molecules (p105 and p100), which can act as inhibitors of NF-κB(IκB) proteins. The activation of the NF-κB pathway is controlled by IκB proteins, which retain NF-κB in the cytoplasm. Following activation, they are degraded by the proteasome while NF-κB translocates into the nucleus where it activates transcription.2 The IκB kinase (IKK) complex plays a central role in this pathway by mediating the initial phosphorylation of IκB proteins.4

The Bcl-3 protein shares structural features with IκB proteins.5,6 It was initially discovered by investigation of the t(14;19)(q32.3; q13.2) translocation in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL), which is associated with poor prognosis.7 In line with an oncogenic function, Eμ–Bcl-3 transgenic mice develop lymphoproliferative disorders,8 Bcl-3 directly transforms cells,9 and Bcl-3 excerts an antiapoptotic effect in B and T lymphocytes.10,11 Furthermore, Bcl-3 overactivity has been suggested to be involved in the pathogenesis of breast cancer,12 and Bcl-3 overexpression has been reported in a subgroup of anaplastic large-cell lymphomas (ALCLs).13 Consistent with a noninhibitory function, Bcl-3 is located mainly in the nucleus, and it can function as a regulator at NF-κB DNA binding sites.5,6,14-17 Bcl-3–mediated regulation of NF-κB activity might occur indirectly by dissociation of the inhibitory NF-κB (p50)2 and (p52)2 complexes from DNA5 or, alternatively, by a function as transcriptional coactivator.16-18

ALCLs are unique lymphomas originating from cytotoxic T cells (for recent review see Stein et al19 ). They are defined by the proliferation of predominantly large lymphoid cells and expression of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–receptor family member CD30 and the cytotoxic molecules perforin and granzyme B. ALCLs express the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) in 50% to 70% of the cases,19 most commonly in the context of the chromosomal translocation t(2;5)(p23;q35). The resulting nucleophosmin (NPM)–ALK fusion protein promotes cellular transformation. ALCLs share a number of molecular aberrations with classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL), which in the majority of cases derives from B cells.20 Constitutive AP-1 (c-Jun and JunB)21 or Notch-1 overactivity22 is found in both of these lymphoma entities. Interestingly, the B-cell–derived neoplastic Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells of cHL have lost the B-cell–specific gene expression program,23 whereas the T-cell–derived ALCLs have lost most of the expression of T-cell–specific genes,24 supporting the view of a biologic analogy between both entities. Furthermore, both lymphoma types overexpress the TNF receptor family member CD30.19

CD30 has been proposed to contribute to the unique activation of the NF-κB pathway in the HRS cells of cHL.25 The NF-κB–dependent gene expression pattern as well as genomic alterations of the NF-κB/IκB system in HRS cells strongly support the finding that NF-κB is a key regulator of HRS cell biology.26-30 This raises the question about the activity of the NF-κB system in ALCL cells, in particular since the NPM-ALK fusion protein has been shown to suppress activation of NF-κB.31 We describe a constitutive activation of NF-κB (p50)2 in ALCL, but also in HRS cells. We show, in accordance with previously published data,13 an elevated expression of Bcl-3, which is able to induce (p50)2 activity, in ALCL. In addition, we demonstrate a Bcl-3 deregulation in cHL. Thus, Bcl-3 deregulation is the first defect of the NF-κB system found in both these tumor entities. The overexpression of Bcl-3–dependent target genes, in particular in ALCL cell lines, and the identification of gains of the BCL3 gene locus in half of the HRS cell lines and 25% of primary ALCL cases by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis underlines the importance of this finding.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture conditions

HRS (L428, L1236, HDLM-2, KM-H2), ALCL (FE-PD, t(2;5) negative, K299, SU-DHL-1, DEL, JB6, all t(2;5) positive), Reh (pro-B lymphoblastic leukemia), Namalwa, Daudi (both Burkitt lymphoma), Jurkat, KE-37, Molt-4, CEM, H9 (all established from human T-cell leukemias), and HEK293 cells were cultured as described previously.21 Cells were treated with 20 ng/mL TNF-α, where indicated.

Protein preparation and immunoblotting

Whole-cell, cytoplasmic, and nuclear extracts were prepared as described.21 Protein samples (20 μg whole-cell extracts, 5 μg nuclear extracts/lane) were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto nitrocellulose filters (Schleicher and Schuell, Dassel, Germany). The filters were blocked (1% nonfat dry milk, 0.1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris [pH 7.5]) and incubated with the following 1:1000 diluted primary antibodies: monoclonal IKKα (Pharmingen, Heidelberg, Germany), monoclonal Bcl-3 (C-14), monoclonal anti-TRAF1, polyclonal anti-p65 (A), polyclonal anti-p50 (NLS; all from Santa Cruz, Heidelberg, Germany), polyclonal anti–c-IAP2 (Trevigen; Biozol, Eching, Germany), polyclonal anti–Bcl-xL (Transduction Laboratories, Heidelberg, Germany), monoclonal anti-tubulinα (MCA78A; Serotec, München, Germany). Filters were incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies. Bands were visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and IP-shift assay

Preparation of nuclear extracts as well as EMSA analysis were described previously.21 Antibodies used for supershift analysis were polyclonal anti-p65 (A), polyclonal anti-p50 (NLS, H-119; all Santa Cruz), anti-p52 (Upstate Biotechnology, Hamburg, Germany), and anti–c-Rel. Bcl-3 immunoprecipitation followed by gel shift analysis (IP-shift analysis) was performed as described.32 Briefly, whole-cell extracts were prepared (20 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 350 mM NaCl, 20% glycerol, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 1% NP40), and thereafter adjusted to 100 mM NaCl and 1% NP40. Preclearance was performed with protein A–sepharose for 1 hour. The supernatant was incubated with the Bcl-3 antibody (C-14; Santa Cruz) and immunoprecipitates were collected, washed twice with buffer BC-100 (20 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 10% glycerol, 100 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA) containing 1% NP40 and once with buffer BC-100 without NP40. Detergent elution was performed for 15 minutes on ice in buffer BC-100 containing 0.8% deoxycycholic acid (DOC). The resulting supernatant was adjusted to 1.2% NP40. A 10-μL aliquot of the eluate was used in standard EMSA for detection of NF-κB binding activity.

IκB kinase assay

For the analysis of IκB kinase activity, cells were left untreated or treated with 20 ng/mL TNF-α for 15 minutes. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), extracts were prepared using lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 1 μg/mL Pefabloc [SERVA Electrophoresis, Heidelberg, Germany], aprotinin and leupeptin, 10 mM NaF, 8 mM β-glycerophosphate, 100 μM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM DTT [dithiothreitol]). A quantity of 250 μg of each extract was precleared for 30 minutes at 4°C with protein A–sepharose beads (Amersham). For immunoprecipitation, protein A–sepharose beads and 1 μg monoclonal anti-IKKα antibody (Pharmingen) were added for 2 hours at 4°C. The protein A–sepharose was washed 4 times with lysis buffer and once with kinase buffer (20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 20 μM ATP, 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 μM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM DTT). Thereafter, 20 μL kinase buffer, 1 μg purified recombinant GST-IκBα (aa 1-53) and 3 μCi (0.111 MBq) γ-[32P]ATP were added to the protein A–sepharose immunocomplex. The kinase reaction was incubated for 20 minutes at 37°C. Reaction mixtures were boiled and subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

Northern blot analysis

Total RNA was prepared using guanidinium isothiocyanate lysis and CsCl gradient centrifugation as described.33 mRNA preparation was performed according to the PolyATract mRNA Isolation System (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) protocol. mRNA (3 μg) was subjected to gel electrophoresis on a 1.1% formaldehyde–1.2% agarose gel and transferred to a nylon membrane (Appligene, Heidelberg, Germany). After UV cross-linking, the membrane was prehybridized (ExpressHyb solution; Clontech) and thereafter hybridized with α-[32P]deoxycytidine 5′-triphosphate (dCTP)–labeled random prime-labeled DNA probes (IL10, SERPINB1, SLPI, BCL3, IL9, GAPDH) overnight at 68°C. Membranes were washed at room temperature in 2× standard saline citrate (SSC) and 0.05% SDS and then in 0.1× SSC and 0.1% SDS.

Generation of tissue microarrays, immunohistology, and FISH analysis

Tissue microarrays were generated as described previously.34 Briefly, representative areas of the lymph node specimens from 4 natural killer (NK) cell–derived lymphomas, 48 T-cell–derived lymphomas, 72 cases of classic (cHL) and lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (LPHL), 4 borderline cases, and 164 B-cell–derived lymphomas were sampled out in the form of a cylinder and arrayed on three recipient paraffin blocks. All cases were drawn from the files of the Consultation and Reference Center for Haematopathology at the Institute of Pathology, Campus Benjamin Franklin, Medical University Berlin. Final diagnosis had been established after extensive immunohistologic analysis according to the criteria of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification. For immunohistology, the specificity of the Bcl-3 antibody (clone 1E8, Novocastra; Newcastle, United Kingdom) was tested on paraffin-embedded HEK293 cells transfected with Bcl-3 expression plasmid. The antibody required a heat-induced antigen-demasking procedure prior to its application. Specifically, bound antibody was detected using a streptavidin-biotin-peroxidase method and diaminobenzidine as chromogen. Whereas, in most cases, Bcl-3 staining was observed only in the nucleus, in several cases a cytoplasmic staining was also detectable. Staining intensity was classified as weak, intermediate, or strong nuclear staining in more than 50% or less than 50% of the tumor-cell population. For delineation of genomic changes of the BCL3 gene locus, FISH analysis using BAC clone RP11-84C16 derived from chromosome 19q13.3 (German Resource Center, Berlin, Germany) was performed. Pretreatment of slides, hybridization, posthybridization processing, and signal detection were performed as decribed.34 Tumor signals were scored as copy number increase, if more than 10% of cells showed 3 or more signals. As an internal control probe a differently labeled BAC clone (RP11-32H17 derived from chromosme 19q13.2) was used.

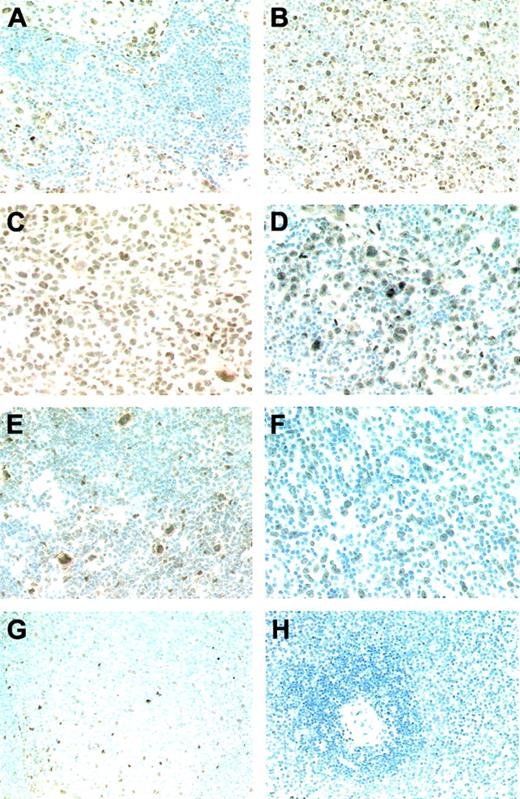

Image acquisition

Specimens were studied using an Olympus Provis AX70 microscope equipped with a range of plan-apochromatic objective lenses (4×/0.13 NA; 10×/0.40 NA; 20×/0.70 NA; 40×/0.95 NA) and coupled with a multicontrol U-MCB box that enabled zooming function (all from Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan). Original magnifications of panels as automatically calculated by the multicontrol U-MCB box are as follows: A, F, and G, × 160; B, × 250; C–E, × 300; and H, × 50. Images were captured directly by a KY-F40 digital camera (Victor, Yokohama, Japan), and were processed with Diskus Program 4.20 (Hilgers Technical, Koenigswinter, Germany), which converted and exported images in tagged-image file format (TIFF).

Results

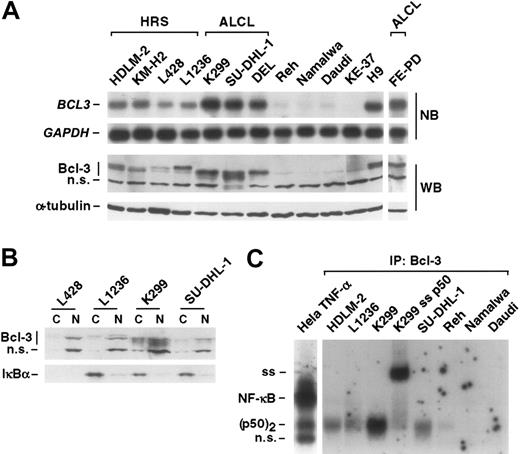

Constitutive NF-κB-Rel activity in ALCL cells predominantly consists of p50 homodimers in the absence of constitutive IKK activation

To compare the NF-κB activity between HRS, ALCL, and other non-Hodgkin cell lines, we analyzed nuclear extracts of unstimulated cells for NF-κB DNA binding activity by EMSA (Figure 1A). Constitutive heterodimeric NF-κB activity was detectable in the HRS cell lines, as decribed.26,27 In addition, in all HRS cell lines p50-homodimers [(p50)2] were detectable (Figure 1A). No comparable NF-κB heterodimeric activity was found in the t(2;5)-positive ALCL cell lines. However, all these cell lines displayed constitutive (p50)2 activation (Figure 1A-B), with strongly elevated (p50)2 in the cell line K299 (Figure 1A-B). The t(2;5)-negative ALCL cell line FE-PD showed a constitutive NF-κB activity comparable to that of HRS cell lines.

To analyze the composition of the NF-κB complex in ALCL cell lines, we performed supershift analysis of nuclear extracts of untreated or TNF-α–stimulated cells with antibodies specific for p50, p65, p52, or cRel (Figure 1B; data not shown). In unstimulated cells, the complex consisted of (p50)2. Following stimulation with TNF-α, NF-κB p50-p65 was rapidly induced, whereas the (p50)2 activity remained unaltered.

In HRS cells, the constitutively active IKK complex induces degradation of IκB proteins, which results in NF-κB activation.35 We therefore compared IKK activity in non-Hodgkin, HRS, and ALCL cell lines by an in vitro kinase assay (Figure 1C). As described,35 compared with the non-Hodgkin cell lines Reh, Namalwa, and Jurkat, the HRS cell lines L428 and L1236 revealed constitutive IKK activity. In unstimulated K299 and SU-DHL-1 ALCL cells, IKK activity was low; in DEL cells, it was as strong as in HRS cells. However, in contrast to HRS cells, in which the IKK complex cannot be further stimulated (Figure 1D; Krappmann et al35 ), IKK activity was strongly TNF-α inducible in all ALCL cell lines. Thus, the NF-κB activity in ALCL cells is distinct from that in HRS cells and the IKK complex is not constitutively activated.

Characterization of NF-κB and IKK activity in ALCL cells. (A) EMSA analysis of unstimulated cells. Nuclear extracts of unstimulated HRS and ALCL cell lines were analyzed for NF-κB DNA binding activity by EMSA. Positions of NF-κB and (p50)2 complexes are indicated. n.s. indicates nonspecific. (B) Induction of NF-κB p50-p65 activity in K299 ALCL cells. Nuclear extracts of unstimulated or TNF-α–treated K299 cells were analyzed with or without preincubation with the indicated antibodies for supershift (ss) analysis by EMSA for NF-κB DNA binding activity. Positions of NF-κB and (p50)2 complexes are indicated. n.s. indicates nonspecific. (C, D) Analysis of IKK activity in unstimulated or TNF-α–treated cell lines, as indicated. (C) IKK activity in unstimulated cells was determined by an in vitro kinase assay (KA). IKKα was immunoprecipitated using a monoclonal antibody against IKKα and protein A–sepharose. The precipitates were incubated with GST-IκBα (aa 1-53) and γ-[32P]ATP at 37°C and subsequently analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. As control, IKKα expression was analyzed by Western blot. (D) Prior to IKK analysis, cells were treated for 15 minutes with TNF-α. Analysis of the IKK activity was as described in panel C. Note that in panel D the IKK activity between the different cell lines is not comparable.

Characterization of NF-κB and IKK activity in ALCL cells. (A) EMSA analysis of unstimulated cells. Nuclear extracts of unstimulated HRS and ALCL cell lines were analyzed for NF-κB DNA binding activity by EMSA. Positions of NF-κB and (p50)2 complexes are indicated. n.s. indicates nonspecific. (B) Induction of NF-κB p50-p65 activity in K299 ALCL cells. Nuclear extracts of unstimulated or TNF-α–treated K299 cells were analyzed with or without preincubation with the indicated antibodies for supershift (ss) analysis by EMSA for NF-κB DNA binding activity. Positions of NF-κB and (p50)2 complexes are indicated. n.s. indicates nonspecific. (C, D) Analysis of IKK activity in unstimulated or TNF-α–treated cell lines, as indicated. (C) IKK activity in unstimulated cells was determined by an in vitro kinase assay (KA). IKKα was immunoprecipitated using a monoclonal antibody against IKKα and protein A–sepharose. The precipitates were incubated with GST-IκBα (aa 1-53) and γ-[32P]ATP at 37°C and subsequently analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. As control, IKKα expression was analyzed by Western blot. (D) Prior to IKK analysis, cells were treated for 15 minutes with TNF-α. Analysis of the IKK activity was as described in panel C. Note that in panel D the IKK activity between the different cell lines is not comparable.

Bcl-3 in ALCL and HRS cells. (A) mRNA and protein expression of Bcl-3 in Hodgkin, ALCL, and other non-Hodgkin cell lines, as indicated. Top panel: mRNA analysis of BCL3 and, as control, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) by Northern blot (NB). Bottom panel: protein expression of Bcl-3 in various lymphoma cell lines, as indicated. As a control, expression of α-tubulin is shown. WB indicates Western blot. (B) Localization of Bcl-3. Cytoplasmic (C) and nuclear (N) extracts of Hodgkin (L428, L1236) and ALCL (K299, SU-DHL-1) cells were analyzed for localization of Bcl-3 and IκBα by Western blot analysis. Note that L428 HRS cells lack expression of IκBα WT protein. (C) Bcl-3 IP-shift assay. Bcl-3 containing NF-κB complexes of HRS (HDLM-2, L1236), ALCL (K299, SU-DHL-1), and other non-Hodgkin cell lines (Reh, Namalwa, Daudi) were immunoprecipitated by use of an anti–Bcl-3 antibody. Thereafter, precipitated complexes were analyzed with or without supershift (ss) analysis for NF-κB DNA binding activity by EMSA. Nuclear extracts of TNF-α–stimulated Hela cells are shown as control. Positions of NF-κB and (p50)2 complexes are indicated. n.s. indicates nonspecific; IP, immunoprecipitation.

Bcl-3 in ALCL and HRS cells. (A) mRNA and protein expression of Bcl-3 in Hodgkin, ALCL, and other non-Hodgkin cell lines, as indicated. Top panel: mRNA analysis of BCL3 and, as control, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) by Northern blot (NB). Bottom panel: protein expression of Bcl-3 in various lymphoma cell lines, as indicated. As a control, expression of α-tubulin is shown. WB indicates Western blot. (B) Localization of Bcl-3. Cytoplasmic (C) and nuclear (N) extracts of Hodgkin (L428, L1236) and ALCL (K299, SU-DHL-1) cells were analyzed for localization of Bcl-3 and IκBα by Western blot analysis. Note that L428 HRS cells lack expression of IκBα WT protein. (C) Bcl-3 IP-shift assay. Bcl-3 containing NF-κB complexes of HRS (HDLM-2, L1236), ALCL (K299, SU-DHL-1), and other non-Hodgkin cell lines (Reh, Namalwa, Daudi) were immunoprecipitated by use of an anti–Bcl-3 antibody. Thereafter, precipitated complexes were analyzed with or without supershift (ss) analysis for NF-κB DNA binding activity by EMSA. Nuclear extracts of TNF-α–stimulated Hela cells are shown as control. Positions of NF-κB and (p50)2 complexes are indicated. n.s. indicates nonspecific; IP, immunoprecipitation.

Bcl-3 overexpression and overactivity of Bcl-3–(p50)2 in ALCL and HRS cell lines

Overexpression of Bcl-3 has been shown to increase (p50)2 DNA binding activity.6 We therefore investigated the expression level of Bcl-3 in the different cell lines (Figure 2A). In accordance with previous observations,13 we detected increased BCL3 mRNA levels in all ALCL cell lines, including the t(2;5)-negative cell line FE-PD. In addition, elevated BCL3 mRNA expression levels were found in HRS cell lines (Figure 2A) as well as in the acute T-cell leukemia cell line H9. Bcl-3 expression was confirmed at the protein level (Figure 2A). Bcl-3 protein revealed marked differences in the migration pattern, presumably reflecting differences in the phosphorylation status.14

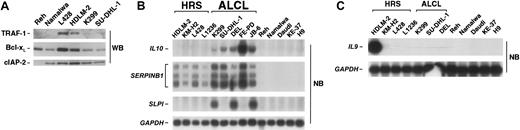

Expression of NF-κB–or Bcl-3–dependent target genes and IL9 in lymphoma cell lines. (A) Expression analysis of classic NF-κB target genes. Whole-cell extracts of various lymphoma cell lines were analyzed for expression of TRAF-1, Bcl-xL, and cIAP-2 by Western blot. (B) Expression of Bcl-3–dependent genes. mRNA analysis of IL10, SERPINB1, SLPI, and, as control, GAPDH of various lymphoma cell lines by Northern blot. (C) IL9 mRNA expression analysis of various lymphoma cell lines by Northern blot. GAPDH expression is shown as control.

Expression of NF-κB–or Bcl-3–dependent target genes and IL9 in lymphoma cell lines. (A) Expression analysis of classic NF-κB target genes. Whole-cell extracts of various lymphoma cell lines were analyzed for expression of TRAF-1, Bcl-xL, and cIAP-2 by Western blot. (B) Expression of Bcl-3–dependent genes. mRNA analysis of IL10, SERPINB1, SLPI, and, as control, GAPDH of various lymphoma cell lines by Northern blot. (C) IL9 mRNA expression analysis of various lymphoma cell lines by Northern blot. GAPDH expression is shown as control.

Bcl-3 shuttles and is predominantly located in the nucleus, where it preferentially binds to (p50)2.14 The analysis of cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts of different HRS and ALCL cell lines revealed Bcl-3 mainly in nuclear fractions (Figure 2B). This was in contrast to IκBα (Figure 2B), which was mainly cytoplasmic. Bcl-3–p50 complexes bound to the NF-κB DNA binding sites are difficult to detect by conventional methods analyzing NF-κB activity. We described a method to detect these complexes by IP-shift assay.32 Bcl-3–NF-κB complexes were immunoprecipitated with a Bcl-3–specific antibody, and NF-κB/Rel activity released from Bcl-3 was analyzed by EMSA (Figure 2C). Following Bcl-3 immunoprecipitation, DNA binding of (p50)2 was detectable in HRS and ALCL cell lines. The strongest activity was found in K299 cells. These data indicate association of Bcl-3 with (p50)2 in HRS and ALCL cells, but not in the other cell lines investigated.

Bcl-3–dependent but not “classic” NF-κB–dependent target genes are highly overexpressed in ALCL cell lines

The constitutive activity of NF-κB in HRS cells is responsible for expression of a number of antiapoptotic, cell-cycle regulating, and cell-surface receptor proteins.27,28 We therefore compared expression of Bcl-xL, c-IAP2, and TRAF-1 between HRS and ALCL cells (Figure 3A). As expected, the HRS cell lines L428 and HDLM-2 strongly expressed TRAF1, Bcl-xL, and, less intensely, c-IAP2. In contrast, expression of these NF-κB target genes was not elevated in ALCL cell lines. These results are in agreement with the absence of constitutive IKK and NF-κB p50-p65 activities. However, a number of recently identified Bcl-3–dependent target genes,9,36 including IL10, SERPINB1, and SLPI (Figure 3B) proved to be strongly expressed in ALCL, and less strongly and consistently, in HRS cell lines. Importantly, no expression of these genes was detectable in Bcl-3–negative cell lines.

IL9 expression does not correlate with BCL3 expression in HRS and ALCL cell lines

Since IL-9 induces Bcl-3 in certain cell types37 and has been reported to be specifically overexpressed in primary cases of cHL and ALCL,38 we investigated IL-9 expression in the diverse cell lines. Only HDLM-2 cells expressed IL9 (Figure 3C). This argues against an involvement of IL-9 in Bcl-3 up-regulation in these cell lines.

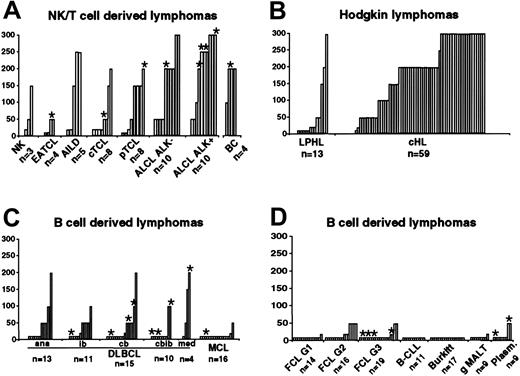

Bcl-3 overexpression in cHL, ALCL, and other peripheral T-cell lymphomas

To study Bcl-3 expression in a large collection of primary lymphomas, we performed immunhistochemical staining in 72 cases of HL (13 cases of LPHL, 59 cases of cHL), 48 cases of NK/T-cell–derived lymphomas (including 10 cases of ALK-negative and 10 cases of ALK-positive ALCL), 4 borderline cases between ALK-negative ALCL and cHL, as well as 164 cases of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas (Figures 4, 5). Staining of primary lymphoma cells showed a characteristic nuclear Bcl-3 staining (Figure 5). The immunohistochemical analysis was in accordance with the in vitro analysis. Among 59 cases of cHL, most showed an intermediate or strong nuclear staining for Bcl-3 in the HRS cells (44/59; 74.5%). There were 13 of 59 cases that stained weakly (22%), and only 2 cases did not stain for Bcl-3 (2/59; 3.3%). Among cases of LPHL, the lymphocytic and histiocytic (L&H) cells in 3 of 13 (23%) cases stained intermediately or strongly, 2 of 13 cases stained weakly (15.3%), whereas 8 of 13 (61.5%) cases were negative for Bcl-3. In the ALCL group, 13 of 20 cases (65%) showed intermediate or strong nuclear staining, 7 of 20 stained weakly (35%), whereas no case lacked Bcl-3 expression. We did not observe a difference between ALK-positive or ALK-negative cases. Thus, deregulated Bcl-3 expression is frequently found in primary HL and ALCL.

Bcl-3 expression in primary lymphomas on tissue microarrays. Each column represents one single lymphoma case. (A) NK/T-cell–derived lymphomas and borderline cases (n = 52; NK, natural killer cell lymphoma; EATCL, enteropathy-type TCL; AILD, angioimmunoblastic TCL; cTCL, primary cutaneous TCL; pTCL, peripheral TCL unspecified; ALCL, anaplastic large-cell lymphoma; BC, borderline cases between ALK-negative ALCL and cHL), (B) Hodgkin lymphomas (n = 72; LPHL, lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma; cHL, classic HL), and (C, D) other B-cell–derived lymphomas (n = 164; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; ana, anaplastic variant; ib, immunoblastic variant; cb, centroblastic variant; cbib, centro-/immunoblastic variant; med, primary mediastinal; MCL, mantle-cell lymphoma; FCL, follicular lymphoma; gMALT, gastric marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue; Plasm, plasmacytoma) were analyzed for Bcl-3 expression by immunohistochemistry. Staining intensity was: absent, 10; single positive cells, 20; weak, < 50%, 50; weak, 100; intermediate, < 50%, 150; intermediate, 200; strong, < 50%, 250; strong, 300. *Copy number increases (3 or more signals) of the BCL3 gene locus, analyzed by FISH.

Bcl-3 expression in primary lymphomas on tissue microarrays. Each column represents one single lymphoma case. (A) NK/T-cell–derived lymphomas and borderline cases (n = 52; NK, natural killer cell lymphoma; EATCL, enteropathy-type TCL; AILD, angioimmunoblastic TCL; cTCL, primary cutaneous TCL; pTCL, peripheral TCL unspecified; ALCL, anaplastic large-cell lymphoma; BC, borderline cases between ALK-negative ALCL and cHL), (B) Hodgkin lymphomas (n = 72; LPHL, lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma; cHL, classic HL), and (C, D) other B-cell–derived lymphomas (n = 164; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; ana, anaplastic variant; ib, immunoblastic variant; cb, centroblastic variant; cbib, centro-/immunoblastic variant; med, primary mediastinal; MCL, mantle-cell lymphoma; FCL, follicular lymphoma; gMALT, gastric marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue; Plasm, plasmacytoma) were analyzed for Bcl-3 expression by immunohistochemistry. Staining intensity was: absent, 10; single positive cells, 20; weak, < 50%, 50; weak, 100; intermediate, < 50%, 150; intermediate, 200; strong, < 50%, 250; strong, 300. *Copy number increases (3 or more signals) of the BCL3 gene locus, analyzed by FISH.

Bcl-3 staining of primary lymphomas (all immunoperoxidase with hematoxylin counterstain). (A) Strong nuclear expression of Bcl-3 in all neoplastic cells of an ALK-positive ALCL case with an intrasinusoidal growth pattern. (B) Variable expression intensity of Bcl-3 ranging from strong to intermediate in sheets of neoplastic cells of a further ALK-positive ALCL case. (C) The expression pattern of ALK-negative ALCL is similar to that of the ALK-positive cases. (D) The Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells of a cHL case show a predominantly strong nuclear Bcl-3 expression. Also, cells of the surrounding inflammatory background infiltrate display a weak Bcl-3 expression. (E) Detection of a strong nuclear Bcl-3 expression in the L&H cells of an LPHL case accompanied by faintly labeled bystander cells. (F) Bcl-3 expression in the neoplastic cells of a DLBCL, whereas the numerous non-neoplastic smaller lymphocytes of the background infiltrate are completely Bcl-3 negative. (G) Within normal lymphoid tissue, a weak nuclear Bcl-3 expression is solely observed in follicular dendritic cells of germinal centers. (H) No Bcl-3–expressing cells are detectable in the white and red pulp of the spleen.

Bcl-3 staining of primary lymphomas (all immunoperoxidase with hematoxylin counterstain). (A) Strong nuclear expression of Bcl-3 in all neoplastic cells of an ALK-positive ALCL case with an intrasinusoidal growth pattern. (B) Variable expression intensity of Bcl-3 ranging from strong to intermediate in sheets of neoplastic cells of a further ALK-positive ALCL case. (C) The expression pattern of ALK-negative ALCL is similar to that of the ALK-positive cases. (D) The Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells of a cHL case show a predominantly strong nuclear Bcl-3 expression. Also, cells of the surrounding inflammatory background infiltrate display a weak Bcl-3 expression. (E) Detection of a strong nuclear Bcl-3 expression in the L&H cells of an LPHL case accompanied by faintly labeled bystander cells. (F) Bcl-3 expression in the neoplastic cells of a DLBCL, whereas the numerous non-neoplastic smaller lymphocytes of the background infiltrate are completely Bcl-3 negative. (G) Within normal lymphoid tissue, a weak nuclear Bcl-3 expression is solely observed in follicular dendritic cells of germinal centers. (H) No Bcl-3–expressing cells are detectable in the white and red pulp of the spleen.

Among the 164 cases of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas, only 4 cases (2.4%) stained intermediately (no case stained strongly), and in 132 cases (80.5%) Bcl-3 expression was absent. Thus, elevated Bcl-3 expression is a rare event in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. In contrast, among the 25 cases of peripheral T-cell lymphomas (apart from ALCL), 2 cases stained strongly, 7 intermediately, and 5 weakly for Bcl-3 (together 56%), whereas 11 cases (44%) did not stain for Bcl-3. Thus, Bcl-3 overexpression is regularly found in peripheral T-cell lymphomas. B and T lymphocytes of normal lymphoid tissue (activated tonsillar lymphoid tissue from 6 patients, spleen sections from 3 patients) did not stain for Bcl-3. This indicates that the level of Bcl-3 expression detectable in lymphomas is a feature of neoplastic cells.

Delineation of copy number changes of the BCL3 gene locus

To investigate the mechanisms of Bcl-3 up-regulation, we analyzed the BCL3 locus of the ALCL cell lines K299, SU-DHL-1, and 6 HL-derived cell lines (L1236, HDLM-2, KM-H2, L428, HD-My-Z, L540). In SU-DHL-1 cells, 7 BCL3 signals were detected, 3 from normal chromosomes and 4 from a marker chromosome, whereas in K299 cells no increase of copy number was apparent. Similar results have been described by Nishikori et al,13 with the exception of K299, in which three BCL3 signals have been previously observed. Among the HL cell lines, three showed additional BCL3 copies: L1236 and L540 (three signals/cell, respectively) and L428 (4 signals/cell). In addition to the cell lines, FISH analysis was performed with the primary lymphomas analyzed by immunohistochemistry, except for cHL cases. In the group of T-cell lymphomas, FISH analysis was possible in 37 of 45 cases. In 8 of the 37 cases, gains of BCL3 copy number were detectable (Figure 4, asterisks). Most of them showed an intermediate or strong BCL3 expression level. Remarkably, 5 of the 8 cases were ALCL. Among the borderline cases, one with intermediate Bcl-3 expression showed a gain for BCL3.

Among the 164 cases of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas, BCL3 FISH analysis could be evaluated in 109 cases. In 3 cases more than 4 signals/cell could be identified (Figure 4, asterisks): 1 case with plasmacytoma, 1 case with mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, and 1 case with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the centroblastic variant. Immunohistochemical analysis showed Bcl-3 expression in all 3 cases. Furthermore, 3 to 4 signals per cell were identified in 13 cases. Among these, in 3 cases Bcl-3 expression was detectable, whereas the other 10 cases did not stain for Bcl-3.

Discussion

We describe a constitutive activity of NF-κB p50 homodimer [(p50)2] in ALCL (Figure 1A-B). We also found an elevated (p50)2 activity in HRS cells of cHL, although in these cells the NF-κB activity consists mainly of heterodimeric complexes (Figure 1A, Bargou et al26 ). In light of the observation that (p50)2 activation can be induced by Bcl-3,6,17 we studied the expression and function of Bcl-3 in ALCL and cHL. We could confirm an overexpression of Bcl-3 in ALCL cell lines,13 but found in addition an up-regulation of Bcl-3 in HRS cell lines (Figure 2). In both types of cell lines, Bcl-3 proved to be located mainly in the nucleus (Figure 2B) and to be associated with (p50)2 (Figure 2C). Importantly, the majority of primary ALCL, independent of ALK expression, and of primary cHL cases showed a nuclear staining for Bcl-3 (Figures 4, 5). Thus, deregulated Bcl-3 expression is a common defect in both these CD30+ lymphoma entities. These findings demonstrate that Bcl-3 does not discriminate ALCL from cHL, contrary to the suggestion by Nishikori et al.13 This discrepancy might be due to the higher level of BCL3 mRNA in ALCL compared with cHL (Figure 2), which does not directly reflect Bcl-3 protein expression in primary tumors, analyzed by immunohistochemistry (Figure 5).

There are 2 major pathways that can induce Bcl-3–p50 complexes. One involves IKK-dependent degradation of p105.32 Thereby, liberated (p50)2 associate with Bcl-3. This pathway appears not to be activated in ALCL or HRS cell lines, since the IKK complex is not constitutively active in ALCL cell lines (Figure 1) and the level of p105 and p50 in ALCL and HRS cell lines is comparable to that in other non-Hodgkin cell lines (data not shown). The second pathway induces Bcl-3–p50 complexes by overexpression of Bcl-3 itself.6,17 Bcl-3 thereby associates, independently of p105 degradation, with p50 released from p105-p50 complexes. The data presented are in favor of this mechanism in the investigated cell lines.

Bcl-3 does not activate transcription of “classic” NF-κB target genes, which are activated by NF-κB heterodimeric complexes. This was revealed for the ALCL cell lines by showing that there is no overexpression of Bcl-xL, TRAF-1, cIAP-2, or c-FLIP (Figure 3; Mathas et al28 ) demonstrable in these cell lines. For some of these genes, the lack of expression was also verified in primary ALCL cells,39 which supports the significance of our cell-line data. The recently described inhibition of CD30-induced NB-κB heterodimeric activity by the NPM-ALK fusion protein31 might explain the lack of expression of these genes in t(2;5)-positive ALCL cells, although IKK and NF-κB heterodimeric activity is inducible by TNF-α in ALCL cell lines (Figure 1). A small number of Bcl-3 target genes has been identified, among these CCND1, SELP, IL10, SLPI, and SERPINB1.9,36,40,41 Whereas the first 2 genes did not show elevated expression in ALCL cells (data not shown), the latter 3 are strongly overexpressed in ALCL, and less strongly and consistently in HRS cell lines (Figure 3B). These data argue for a transcriptional activity of Bcl-3 at least in ALCL cells. Of interest, 2 of these genes are protease inhibitors, which were reported to promote growth and invasiveness of malignant cells.42

Little is known about the regulation of Bcl-3 expression. In t(14;19)(q32.3;q13.2)-positive B-CLL, Bcl-3 expression results from chromosomal translocation.7 Bcl-3 up-regulation is inducible by mitogenic stimuli or cytokines including IL-9.7,37 Although IL-9 expression has been described in ALCL and cHL,38 only HDLM-2 cells showed IL9 expression (Figure 3). Thus, IL-9 does not generally enforce Bcl-3 expression in the cell lines. However it cannot be excluded that it might contribute to elevation of Bcl-3 in primary tumor cells. NF-κB p50-p65 might induce Bcl-3 by an autoregulatory loop.43 However, NF-κB p50-p65 is not consistently activated in ALCL cell lines (Figure 1), and BCL3 was not detected as an NF-κB–regulated gene in HRS cell lines.27 Transcription factor activator protein 1 (AP-1), showing a unique overactivity in cHL and ALCL,21 has been reported to induce Bcl-3 in T cells.11 Whether Bcl-3 in ALCL and cHL is AP-1 dependent has to be determined in future analyses. Vice versa, Bcl-3 stimulates AP-1 transactivation,44 which might enhance AP-1–dependent transcription in these cells.

In a search for genetic alterations that might be involved in the up-regulation of Bcl-3, we performed FISH analysis of the BCL3 locus (Figure 4; data not shown). In SU-DHL-1 cells and 3 of 6 HL cell lines, the BCL3 gene was found amplified. More importantly, we identified gains of the BCL3 gene in several T-cell lymphomas, including 25% of primary ALCLs. Apart from gains of the BCL3 gene, epigenetic modification of a 3′CpG island of the BCL3 gene was described in ALCL,13 which might enforce Bcl-3 expression.

The mechanisms of Bcl-3–mediated transformation are currently unclear. There is accumulating evidence that Bcl-3 protects lymphocytes, in particular T lymphocytes, from apoptotic cell death.10,11 In line with these data, we detected, in addition to ALCL and cHL, Bcl-3 overexpression in various entities of primary human peripheral T-NHL (Figure 4). We propose that deregulation of Bcl-3 delivers an important survival signal for T-cell–derived lymphomas in general. In addition, the Bcl-3–triggered expression of protease inhibitors might promote tumor growth by modulation of the tumor microenvironment.42 Regarding ALCL, NPM-ALK–transformed cells induce lymphomas in mouse models,45 which demonstrates the oncogenic activity of this fusion protein. However, in these mouse models no NPM-ALK–induced lymphoma with a mature T-cell phenotype comparable to ALCL has yet been observed. Thus, further alterations are required for the formation of ALCL. One of these alterations might be overexpression of Bcl-3.

Our findings suggest an important function of Bcl-3 for distinct human lymphoma entities, in particular ALCL and cHL. In addition, apart from mutations of IκB proteins,30 constitutive IKK activity,35 and genomic alterations of the Rel locus,29 altered Bcl-3 expression defines a further defect of the NF-κB system in HRS cells.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, August 25, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3620.

Supported in part by the German Ministry for Education and Research (National Network for Genome Research, NGFN-1 P2T02 and NGFN-2 01GR0417), the Berliner Krebsgesellschaft, and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Klinische Forschergruppe KFO105).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Vigo Heissmeyer (Berlin, Germany) and Benjamin Mordmüller (Berlin, Germany) for helpful discussion.

![Figure 1. Characterization of NF-κB and IKK activity in ALCL cells. (A) EMSA analysis of unstimulated cells. Nuclear extracts of unstimulated HRS and ALCL cell lines were analyzed for NF-κB DNA binding activity by EMSA. Positions of NF-κB and (p50)2 complexes are indicated. n.s. indicates nonspecific. (B) Induction of NF-κB p50-p65 activity in K299 ALCL cells. Nuclear extracts of unstimulated or TNF-α–treated K299 cells were analyzed with or without preincubation with the indicated antibodies for supershift (ss) analysis by EMSA for NF-κB DNA binding activity. Positions of NF-κB and (p50)2 complexes are indicated. n.s. indicates nonspecific. (C, D) Analysis of IKK activity in unstimulated or TNF-α–treated cell lines, as indicated. (C) IKK activity in unstimulated cells was determined by an in vitro kinase assay (KA). IKKα was immunoprecipitated using a monoclonal antibody against IKKα and protein A–sepharose. The precipitates were incubated with GST-IκBα (aa 1-53) and γ-[32P]ATP at 37°C and subsequently analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. As control, IKKα expression was analyzed by Western blot. (D) Prior to IKK analysis, cells were treated for 15 minutes with TNF-α. Analysis of the IKK activity was as described in panel C. Note that in panel D the IKK activity between the different cell lines is not comparable.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/106/13/10.1182_blood-2004-09-3620/2/m_zh80240588080001.jpeg?Expires=1763500901&Signature=GqfEFwKX397Jlubyif~qTBwkY0-mm5hiPQrKOExZ8fBkrSNgitJZrwJ2tVBfXOTlGHzxOXGXcgq~JYYmgjDVEOGyXiJR590HUhiEKgg5PeF44AZRFyRf-iDo9uGZGcDWhQjw4xQFfQ4ouDg~TmKScvgt2Vd8rnWH22ReOtqG3IkP4L~4E6-DpwGHuP-Tkg39iaowhNKgOEdREkd0dk2RLm3fxSaQVy~Q6cMSEtnEDg0CHmMdNA~Yv6Vj4lrIfH1zziyGB2rfm0QxoJSHgJHJtIvu6IO8vRRJs0IsWMtTrpnDPuwoq01AqBDPz-pQQzdP6yrqWebQn99DSLew~dVkCg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal