Comment on Statkute et al, page 2700

Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation can now be performed safely even in most difficult SLE patients when conducted by highly experienced teams.

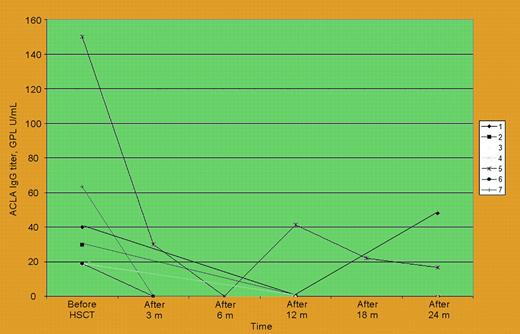

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multisystem autoimmune disease ranging from a relatively mild condition to a severe life-threatening disorder. There are several mechanisms by which autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) may improve autoimmune diseases such as SLE.1 Since 1996 about 100 patients worldwide have received intensive immunoablation and autologous HSCT as investigational therapy for severe refractory SLE. Primary concerns that relate to autologous HSCT as treatment for SLE center on transplantation-related mortality (TRM), which has occurred in up to 12% of patients, and uncertain long-term therapeutic benefit due to short follow-up and the heterogeneity of patients enrolled in the initial trials from more than 23 transplantation teams.2,3 Furthermore, limited information is available regarding immunologic mechanisms that accompany SLE responses after autologous HSCT. In this issue, work by Statkute and colleagues addresses some of these areas of interest. They report a series of 28 patients with refractory SLE and manifestations of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) that were selected out of a larger cohort of 46 patients who received transplants at Northwestern University: 20 patients had definite APS by Sapporo criteria (2 had catastrophic APS). This study, which is the largest single center series of autologous HSCT for SLE reported to date, demonstrates that autologous HSCT can be performed safely even in the clinically most complicated patients if conducted by highly experienced teams, as no TRM was observed. Of interest, autologous HSCT decreased lupus anticoagulant (LA) and anticardiolipin antibodies (ACLAs) in most evaluable patients (see figure), allowed discontinuation of anticoagulation, and induced SLE remission in 78%. This information is novel and contributes positively to the debate on the role of immunosuppression in treating APS. However, there are some study limitations that need to be mentioned. First, only 2 of 28 patients were given transplants for a primary indication of APS as a manifestation of lupus; therefore, any generalization about the utility of autologous HSCT as a therapy for APS in SLE should be drawn with caution. As Statkute and colleagues show, active SLE correlated the best with both recurrent thrombotic events and other clinical APS manifestations, more so than seropositive antiphospholipid antibodies. These data are all consistent with the theory that the key driving process of APS manifestations is SLE-related inflammation. Therefore, it is important to focus on overall SLE outcomes in this study: 21 (75%) of 28 patients with APS entered remission from SLE after autologous HSCT. Only 9 (32%), however, were able to discontinue all immunosuppressive medications and stay in remission during a relatively short median follow-up period of 24 months. The full assessment of this series of autologous HSCT for SLE will not be possible until longer follow-up is available for all patients who received transplants with all their respective SLE outcomes evaluated. This current report, however, firmly establishes the safety and promising efficacy of autologous HSCT for severe SLE. It is reasonable to hypothesize that the next generation of trials will need to focus on developing strategies to further improve the efficacy of current autologous HSCT protocols and perhaps consider even allogeneic HSCT methods on the road toward what should be the ultimate goal: the cure of SLE.4,5 This elusive goal will be possible to achieve only by building strong partnerships and support for investigational networks driven by both disease and transplantation specialists. ▪FIG1

Anticardiolipin IgG antibodies before and serially after stem cell therapy in 7 SLE patients with positive antibody before transplantation. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 2700.

Anticardiolipin IgG antibodies before and serially after stem cell therapy in 7 SLE patients with positive antibody before transplantation. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 2700.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal