Abstract

Human fibrinogen 1 is homodimeric with respect to its γ chains (`γA-γA'), whereas fibrinogen 2 molecules each contain one γA (γA1-411V) and one γ′ chain, which differ by containing a unique C-terminal sequence from γ′408 to 427L that binds thrombin and factor XIII. We investigated the structural and functional features of these fibrins and made several observations. First, thrombin-treated fibrinogen 2 produced finer, more branched clot networks than did fibrin 1. These known differences in network structure were attributable to delayed release of fibrinopeptide (FP) A from fibrinogen 2 by thrombin, which in turn was likely caused by allosteric changes at the thrombin catalytic site induced by thrombin exosite 2 binding to the γ′ chains. Second, cross-linking of fibrin γ chains was virtually the same for both types of fibrin. Third, the acceleratory effect of fibrin on thrombin-mediated XIII activation was more prominent with fibrin 1 than with fibrin 2, and this was also attributable to allosteric changes at the catalytic site induced by thrombin binding to γ′ chains. Fourth, fibrinolysis of fibrin 2 was delayed compared with fibrin 1. Altogether, differences between the structure and function of fibrins 1 and 2 are attributable to the effects of thrombin binding to γ′ chains.

Introduction

Fibrinogen is a multidomain disulfide-linked protein composed of symmetric halves, each consisting of 3 polypeptide chains termed Aα, Bβ, and γ.1 Human fibrinogen can be separated by ion exchange chromatography into 2 major fractions, fibrinogen 1 (peak 1 fibrinogen) and fibrinogen 2 (peak 2 fibrinogen).2,3 Plasma fibrinogen contains approximately 15% fibrinogen 2. Structurally, the 2 fibrinogens differ from each other with respect to the composition of their γ chains. Fibrinogen 1 contains 2 γA chains, each composed of 411 amino acids, whereas heterodimeric fibrinogen 2 molecules each contain one γA and one γ′ chain.3,4 The variant γ′ chain is longer (427 residues) and has a more anionic, carboxyl terminal sequence than the γA chain beyond position 408.4 Alternative mRNA splicing at the exon 9–exon 10 boundaries gives rise to the variant γ′ chain.5

Thrombin binds to fibrinogen at the substrate site through its exosite 1,6-8 thereby mediating cleavage of fibrinopeptide A9-12 and slower cleavage of fibrinopeptide B.13,14 Fibrin assembly commences with the formation of double-stranded twisting fibrils in which fibrin molecules are arranged in a staggered, overlapping manner.15 Subsequently, lateral fibril associations occur, resulting in thicker fibrils and fibers. Concomitant with converting fibrinogen to fibrin, thrombin activates factor XIII to factor XIIIa.16-21 In the presence of factor XIIIa and Ca2+, fibrin undergoes intermolecular covalent cross-linking by the formation of ϵ–amino(γ–glutamyl) lysine isopeptide bonds.22 Generally speaking, intermolecular cross-linking occurs rapidly between γ chains to form γ-dimers and more slowly among α chains to create oligomers and larger α chain–containing multimers.23,24

In recent years several reports have appeared comparing various structural and functional features of fibrin(ogen)s 1 and 2.25-31 Factor XIII has been shown to bind to the fibrinogen γ′ chains26 and thrombin also binds to the γ′ extension in fibrin25 through its exosite 2.32,33 Fibrin 2 reportedly becomes more “extensively” cross-linked by factor XIIIa than does fibrin 1.27,28 Cooper et al29 and Mosesson et al31 demonstrated that fibrin 2 clots developed lower turbidity during clotting than did fibrin 1, and Cooper et al29 attributed this to the observation that fibrinogen 2 released fibrinopeptide (FP) B (but not FPA) more slowly than did fibrinogen 1. Collet et al30 found fibrin clots formed from recombinant homodimeric γ′-containing fibrinogen (γ′-γ′) lysed more slowly than did fibrin formed from fibrinogen 1 (γA-γA), and this agreed with the findings of Falls and Farrell27 on heterodimeric native fibrin 2. Although delayed clot lysis rates have been correlated with thinner fiber matrices,34-36 Collet et al30 found that homodimeric γ′-containing fibrin clots contained somewhat wider fibers than did those from fibrinogen 1. To evaluate these sometimes conflicting observations and to determine the basis for the differences, we compared several of the functional properties of fibrins 1 and 2.

Materials and methods

Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane), glycine, Coomassie Brilliant Blue R250, and dithiothreitol (DTT) were purchased from Aldrich Chemical (Milwaukee, WI). Trasylol (aprotinin) was obtained from Miles (Kankakee, IL), and DE-52 cellulose was from Whatman (Clifton, NJ). Human α–thrombin (3188 U/mg) was obtained from Enzyme Research Laboratories (South Bend, IN). Other chemicals were of the highest purity available from commercial sources.

Human fibrinogen was isolated from pooled citrated plasma by glycine precipitation and was further purified as previously described.37 Fibrinogen fraction I-2 was separated into fibrinogen 1 (γA-γA) and fibrinogen 2 (γA-γ′) by chromatography on DE-52.26 Fibrinogen 1 is factor XIII free because all the contaminating plasma factor XIII elutes with fibrinogen 2. For cross-linking experiments, the resultant fibrinogen 2 was rendered factor XIII free by differential ammonium sulfate precipitation.26 In brief, factor XIII-rich fibrinogen 2, containing the factor XIII protein and activity, was precipitated at 20% saturated ammonium sulfate. The supernatant material, free of factor XIII, was precipitated at 35% saturated ammonium sulfate. Fibrinogens were analyzed for purity by SDS-PAGE38 after 24-hour incubation with 10 mM CaCl2 and 1 U/mL thrombin. These gels showed that fibrin 1 and factor XIII–free fibrin 2 contained bands in the monomeric α, β, and γ positions. Fibrin 2–containing factor XIII had bands in the α-polymer, γ-dimer, and monomeric β positions and bands corresponding to the A* and B subunits of factor XIII. All fibrinogens used in these studies were greater than 97% clottable.

Soluble fibrin monomer was prepared by the method of Belitser et al.39 Fibrinogen and soluble fibrin concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically at 280 nm using an absorbance coefficient (A1%/1 cm) of 15.1.40

Factor XIII was purified from pooled human plasma41 and assayed on factor XIII-free fibrin substrates (prepared from fibrinogen 1) in the presence of 10 mM CaCl2, as described by Loewy et al.42 Factor XIII concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically at 280 nm using an extinction coefficient (A1%/1cm) of 13.8.43 The specific cross-linking activities of the thrombin-activated factor XIII preparations were between 2100 and 2300 Loewy U/mg. XIII was activated to XIIIa by incubation with thrombin (10 U/mL)44 for 30 minutes at 37°C, and the thrombin was then inactivated by incubating with a 5-fold excess of hirudin (50 U/mL).45 SDS-PAGE of XIIIa revealed 2 bands, the active A* subunit (72 kDa) and the B subunit (79 kDa).46 The molecular mass of the A* subunit as determined by mass spectroscopy is 79 kDa.47

Fibrinopeptide and factor XIII activation peptide release was examined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)17 using a Varian Vista model 5000 system controlled by a Varian model 401 microprocessor (Varian Instruments, Palo Alto, CA). Fibrinogen 1 or fibrinogen 2 (3 mg/mL) was mixed with factor XIII (1 mg/mL) in 9.47 mM NaPO4, 137 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 0.1% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 8000, pH 7.4. The reaction was initiated by adding 0.5 U/mL thrombin or 0.5 U/mL Atroxin (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO), and the mixture was incubated at room temperature. Control reactions contained factor XIII (1 mg/mL) and thrombin (0.5 U/mL) or Atroxin (0.5 U/mL; Sigma). At selected intervals the reaction was terminated by incubation in a boiling water bath for 10 minutes. Samples were clarified by centrifugation and applied to an Altex C18 reverse-phase column (0.46 × 25 cm; Rainin Instruments, Woburn, MA) equilibrated with 90% 0.083 M sodium phosphate, pH 3.1, 10% acetonitrile (buffer A). Elution was performed isocratically for the first 10 minutes using a mixture of 85% buffer A/15% buffer B (buffer B; 60% 0.083 M sodium phosphate, pH 3.1, 40% acetonitrile) followed by a linear gradient from 85% buffer A/15% buffer B to 10% buffer A/90% buffer B over 50 minutes. Peptides were detected with a UV detector set at 215 nm (Waters, Milford, MA).

Cross-linking reaction mixtures contained fibrinogen 1 or fibrinogen 2 (3 mg/mL) in 50 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 10 KIU/mL Trasylol, pH 7.4. Cross-linking was initiated by adding factor XIII or factor XIIIa (100 Loewy U/mL; 0.124 μM) and 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) or by adding factor XIII (100 Loewy U/mL; 0.124 μM) and 0.5 U/mL human thrombin. The mixtures were incubated at room temperature for various time periods. Reactions were terminated by adding an equal volume of 2 × Laemmli sample buffer with 1% β-mercaptoethanol, and the products of the reaction were analyzed by SDS-PAGE using the discontinuous buffer system of Laemmli38 on 9% polyacrylamide gels. Gels were stained with 0.5% Coomassie Brilliant Blue R250 in methanol/water/acetic acid (5:5:1), destained in methanol/water/acetic acid (5:5:1) with continuous shaking, and dried. Stained gels were digitized on an Astra 2400S flat bed scanner (UMAX Technologies, Fremont, CA), and the bands were quantified using NIH Image (version 1.62). Results were normalized against the Bβ band region of the gel. When repolymerized fibrin 1 or fibrin 2 was cross-linked, the reaction mixtures contained factor XIII or factor XIIIa (100 Loewy U/mL; 0.124 μM) in 50 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF, and 10 KIU/mL Trasylol, pH 7.4, and the reactions were started by adding solubilized fibrin (3 mg/mL).

Conditions for clot formation and lysis were selected that gave rapid clotting (1 minute or less) and complete clot lysis within 60 minutes or less. Thromboelastography (TEG) requires relatively high fibrinogen levels for the development of adequate amplitude tracings in the absence of platelets or the other plasma proteins.48 Thromboelastographic measurements were carried out at 37°C under physiologic conditions (140 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.4) at a fibrinogen level of 7 mg/mL (20.6 μM) and lys-plasminogen at 2.0 μM. Thromboelastographic measurements were made in a coagulation analyzer (Hellige Thromboelastograph Coagulation Analyzer model 3000R; Haemoscope, Skokie, IL), and tracings were evaluated using standard measurement parameters.49 Nonlysing controls contained plasminogen and Trasylol but not tPA or tPA but not plasminogen.

Fibrin clots prepared from fibrinogen for examination by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were prepared in 0.1 M NaCl, 0.05 M Tris, pH 7.4 buffer (Tris-buffered saline [TBS]) on carbon-formvar–coated 200 mesh gold grids by admixing 4.5 μL fibrinogen solution at 200 μg/mL with 0.5 μL thrombin at a final thrombin concentration of 0.1 U/mL. Fibrin clots prepared from fibrin monomer solutions were prepared from fibrinogen solutions in TBS at 1 mg/mL in TBS that had been clotted at a thrombin concentration of 1 U/mL and then incubated at room temperature for 2 hours. The clots were synerized and then dissolved in 20 mM acetic acid to approximately 1 mg/mL. Clots were formed directly on carbon-formvar–coated 200 mesh gold grids by admixing 0.5 μL monomer solution with 4.5 μL TBS on the grid at a final fibrin concentration of 100 μg/mL. All mixtures were incubated for 3 hours in a humidity chamber, then fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 100 mM HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid), pH 7 buffer containing 0.2% tannic acid, washed with buffer, dehydrated, critical-point dried, sputter coated with goldpalladium, and imaged in a scanning electron microscope (6300F SEM; JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) at 5 kV and a magnification of 10 000×. Fiber diameters were measured on the digitized images using ImageJ software (version 1.34j) on a dual-processor G4 Macintosh computer (Apple, Cupertino, CA).

Determination of the evolution of the fibrin intermediate, α-profibrin, from fibrinogen 1 or fibrinogen 2 solutions was carried out by a method called GPRphoresis, as described.50-52 GPRphoresis uses electrophoresis to cause the countermigration of Gly-pro-arg-pro amide (GPRP-NH2; Bachem Biosciences, King of Prussia, PA) in GPRP-NH2–impregnated gels to separate GPRP-NH2–insoluble fibrin monomers lacking both FPAs (α-fibrin) from a fibrin intermediate termed α-profibrin lacking only one FPA, and it is soluble in buffer solutions lacking GPRP-NH2. After electrophoresis, the band containing α-profibrin comigrates with fibrinogen and is distinguished from it by immunoprobing the gel with an anti–fibrin α17-23 antibody (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) that reacts with α-fibrin or α-profibin but not with fibrinogen. Briefly, thrombin (3 U/μg; Enzyme Research Laboratories, South Bend, IN) was added to fibrinogen solutions (4 mg/mL, final) in 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris, 10 mM EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), pH 7.4 buffer containing 4 mM GPRP-NH2 at a final thrombin concentration of 1 U/mL. At timed intervals, thrombin was inhibited by the addition of Phe-pro-arg chloromethyl ketone (FRPck), 15 μM, final concentration. Before sample loading, a freshly prepared 9 M urea solution was added to a final concentration of 3 M, and then samples were loaded onto 3.5% agarose gels (LE agarose; Ambion, Austin, TX) containing 2.2 mM GPRP-NH2. Electrophoresis was carried out at 120 to 140 V and 120 mA for 4 hours. The fibrin(ogen)–containing gels were fixed by heating the gel at 60°C for 40 minutes in buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]), incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated anti–α17-23 antibody (8 μg/mL, final) containing 0.25% bovine serum albumin (BSA) overnight at 4°C, and then washed with PBS by negative suction. Color was developed for 5 to 10 minutes with diaminobenzidine (DAB) in 0.005% H2O2, and the color reaction was stopped by transferring the gel to a 0.1 M Na azide solution. The gel was washed with H2O and dried, and densitometry was carried out in an Image Station 2000R (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). Densitometric values were expressed as counts per band.

Tyrosine-phosphorylated γ′ 408-427 (YP γ′ 408-427, MW 3375.5) was prepared by 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) chemistry, as described,53 and used in lieu of native sulfated γ′ peptide, with which it is functionally equivalent. The peptide had a purity greater than 98% by HPLC, and the sequence was confirmed by mass spectrometry. The Kcat and Km of the cleavage of S-2238 (D-Phe-Pip-Arg-pNA) (DiaPharma Group, West Chester, OH) were measured in 200 mM NaCl or ChCl2 (choline chloride), 5 mM Tris, 0.1% PEG, pH 8.0 buffer at 25°C in the presence of 20 to 80 μM YP γ′ 408-427, as described.54 Thrombin clotting times of fibrinogen 1 (250 nM) were measured in the presence of 20 to 80 μMYP γ′ 408-427 and 2 nM thrombin in 145 mM NaCl, 5 mM Tris, 0.1% PEG, pH 7.4, at 37°C.

Results

Thrombin-mediated fibrin formation

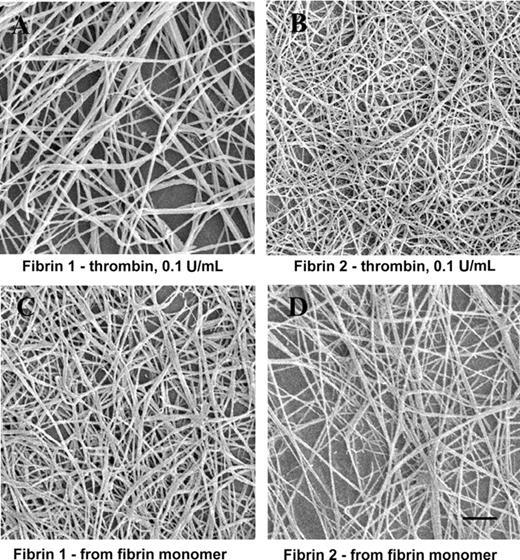

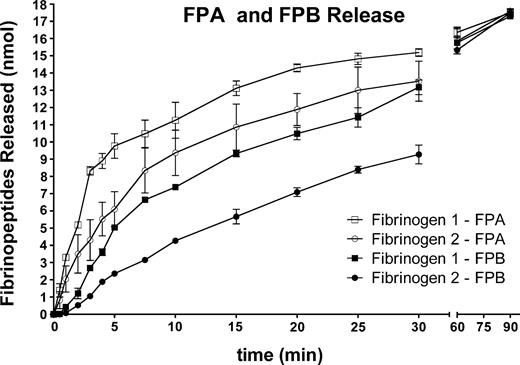

Fibrin formed by the addition of thrombin (0.1 U/mL) to fibrinogen 2 yielded a finer, more branched fiber network than did clots formed under the same conditions from fibrinogen 1 (Figure 1A-B). In contrast, clot networks formed directly from fibrin 1 or fibrin 2 monomer solutions were similar to one another in appearance (Figure 1C-D). Mean fiber widths formed from fibrin 1 or fibrin 2 monomer solutions were not significantly different from one another, and the constituent fibers were somewhat wider in diameter and less branched than those formed from fibrinogen 2 after the addition of thrombin (Table 1). These observations suggested that the structural differences between fibrin 1 and fibrin 2 networks were related to the rate of fibrinopeptide release from fibrinogen. To further explore this possibility, the rate of fibrinopeptide release from fibrinogens 1 and 2 was measured. FPA was released more rapidly from fibrinogen 1 than from fibrinogen 2 (Figure 2) (initial rate, 2.76 nmol/min fibrinogen 1 vs 1.57 nmol/min fibrinogen 2). This was true as well for FPB release (initial rate, 1.04 nmol/min vs 0.51 nmol/min).

Fibrin fiber diameters

Sample . | N . | Mean ± SD, nm . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fibrinogen 1 + IIa | 50 | 124 ± 27 | <.001 |

| Fibrinogen 2 + IIa | 50 | 75 ± 23 | — |

| Fibrin 1 monomer | 50 | 103 ± 24 | >.05 |

| Fibrin 2 monomer | 50 | 105 ± 22 | — |

Sample . | N . | Mean ± SD, nm . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fibrinogen 1 + IIa | 50 | 124 ± 27 | <.001 |

| Fibrinogen 2 + IIa | 50 | 75 ± 23 | — |

| Fibrin 1 monomer | 50 | 103 ± 24 | >.05 |

| Fibrin 2 monomer | 50 | 105 ± 22 | — |

Each P value compares the data in the row in which it is listed to the data in the row below it. — indicates not applicable.

SEM images of fibrin formed by thrombin addition to fibrinogen or by repolymerization of fibrin monomer solutions. (A) Fibrinogen 1 plus thrombin. (B) Fibrinogen 2 plus thrombin. (C) Fibrin 1 monomer. (D) Fibrin 2 monomer. Bar represents 1 μm.

SEM images of fibrin formed by thrombin addition to fibrinogen or by repolymerization of fibrin monomer solutions. (A) Fibrinogen 1 plus thrombin. (B) Fibrinogen 2 plus thrombin. (C) Fibrin 1 monomer. (D) Fibrin 2 monomer. Bar represents 1 μm.

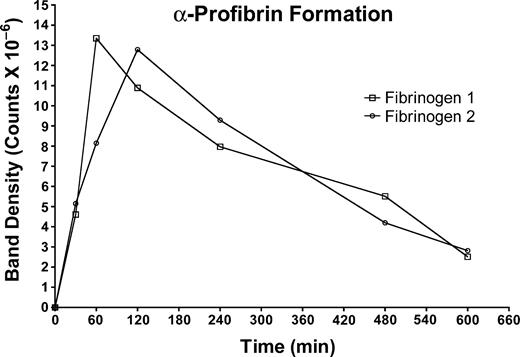

To pursue possible consequences of slower fibrinopeptide release from fibrin 2, the evolution of des-A fibrin (α-profibrin) was evaluated in fibrinogen 1 and 2 (Figure 3). This method requires the presence of GPRP-NH2 in the thrombin-containing reaction mixture.52 We found that the overall rate of fibrinopeptide release was inversely proportional to the concentration of GPRP-NH2, and its presence slowed the rate of peptide release from both fibrinogens. We carried out several α-profibrin generation experiments at concentrations of GPRP-NH2 ranging from 4 to 12 mM, and in every case we observed that α-profibrin generation was slower from fibrinogen 2 than from fibrinogen 1. Thus, the results obtained at 4 mM GPRP-NH2, shown in Figure 3, are representative of our general findings. Inhibition of FPA release from fibrinogen at the relatively high concentrations of GPRP-NH2 used is consistent with the finding of Root-Bernstein and Westfall55 that GPRP binds to FPA with a binding constant of approximately 104. Although the 30-minute time points for α-profibrin generation were similar, subsequent values indicated that α-profibrin was generated more slowly from fibrinogen 2 than from fibrinogen 1. Integration of the curves for each fibrinogen indicated that the overall amount of α-profibrin generated from each fibrinogen was similar (4.30 × 109 counts for peak 1 vs 4.27 × 109 counts for peak 2), a finding in conformance with previous comparisons of fibrinogen 2 and unchromatographed fibrinogen.52

Effect of the γ′ peptide on thrombin activity

The thrombin clotting time of fibrinogen 1 became prolonged in the presence of YP γ′ 408-427 as a function of the concentration of peptide (Table 2). The apparent Kd for YP γ′ 408-427 binding to thrombin derived from these data were 28 ± 12 μM. The effect of YP γ′ 408-427 on the hydrolysis of the thrombin substrate S-2238 in a NaCl environment was noteworthy because the peptide had no effect on Km but reduced the kcat from 22 (no peptide) to 9 second–1 (80 μM peptide), with an apparent Kd of 57 ± 5 μM. This effect demonstrated that YP γ′ 408-427 had reduced the catalytic properties of thrombin through a noncompetitive allosteric mechanism that perturbs the environment of the catalytic triad of the enzyme without significantly perturbing the determinants responsible for substrate binding. Further analysis of YP γ′ 408-427 in ChCl2 also indicated that its effect on thrombin is independent of the allosteric slow→fast transition. In fact, in the absence of Na+, the peptide had no effect on Km and reduced kcat for S-2238 hydrolysis from 2.8 (no peptide) to 0.73 second–1 (80 μM peptide) with an apparent Kd of 48 ± 11 μM. This observation is consistent with the fact that YP γ′ 408-427 binds to exosite II, a region of thrombin that is not involved in the Na+-induced slow→fast transition.56

Time course of fibrinopeptide release from fibrinogen 1 or fibrinogen 2 by thrombin. Reaction was initiated by the addition of thrombin (0.5 U/mL), and at selected intervals the reaction was terminated and fibrinopeptide release was quantified by HPLC. Fibrinogen 1: FPA (□); FPB (▪). Fibrinogen 2: FPA (○); FPB (•).

Time course of fibrinopeptide release from fibrinogen 1 or fibrinogen 2 by thrombin. Reaction was initiated by the addition of thrombin (0.5 U/mL), and at selected intervals the reaction was terminated and fibrinopeptide release was quantified by HPLC. Fibrinogen 1: FPA (□); FPB (▪). Fibrinogen 2: FPA (○); FPB (•).

Evolution of α-profibrin from fibrinogen 1 or fibrinogen 2. Fibrinogen 1 (□); fibrinogen 2 (○). The concentration of GPRP-NH2 in the digestion mixture was 4 mM.

Evolution of α-profibrin from fibrinogen 1 or fibrinogen 2. Fibrinogen 1 (□); fibrinogen 2 (○). The concentration of GPRP-NH2 in the digestion mixture was 4 mM.

Clotting time versus γ′ peptide concentration

γ′ Peptide, μM . | Thrombin time, sec . |

|---|---|

| 0 | 18.6 |

| 20 | 26.6 |

| 40 | 31.0 |

| 80 | 62.4 |

γ′ Peptide, μM . | Thrombin time, sec . |

|---|---|

| 0 | 18.6 |

| 20 | 26.6 |

| 40 | 31.0 |

| 80 | 62.4 |

Measurements contained 250 nM fibrinogen, 2 nM thrombin, and the indicated amount of γ′ peptide in 5 mM Tris, 145 mM NaCl, 0.1% PEG, pH 7.4. Reaction was initiated by adding thrombin and incubating at 37°C.

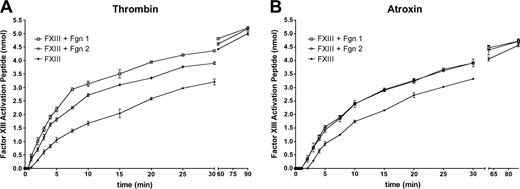

Factor XIII–mediated cross-linking

Farrell and coworkers27 reported that fibrin 2 was more highly cross-linked by factor XIIIa than was fibrin 1, including more extensive γ and α chain cross-linking.28 They also observed that fibrin 2 accelerated plasma factor XIII activation even more so than did fibrin 1.28 To assess these findings we carried out several experiments. Measurements of activation peptide cleavage from factor XIII in the presence or absence of fibrinogen (Figure 4A) confirmed previous reports that activation peptide cleavage from factor XIII by thrombin was faster in the presence of fibrin.16-21 However, we also found, using activation peptide cleavage as an indicator of factor XIII activation, that XIII activation was more rapid in the presence of fibrinogen 1 than it was with fibrinogen 2. These observations conflict with those of Moaddel et al28 with respect to the effect of fibrin 2 on factor XIII activation. To further pursue this point, we also measured factor XIII activation peptide cleavage by Atroxin (Sigma), a snake venom enzyme that cleaves FPA from fibrinogen.57 Atroxin (Sigma) does not, however, bind to the γ′ sequence (K.R.S., unpublished observations, July 1996). Although XIII activation by Atroxin (Sigma) was accelerated by the presence of either fibrinogen, there were no differences in the acceleratory effects (Figure 4B). This last finding indicated that the observed rate differences between fibrin(ogen)s 1 and 2 in a thrombin-catalyzed system were specifically related to thrombin binding to the γ′ sequence.

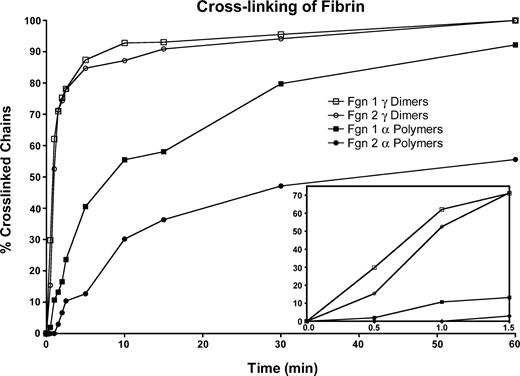

In a cross-linking system in which thrombin was added to a mixture of fibrinogen and factor XIII, the γ-chain cross-linking rate during the first minute was slower for fibrinogen 2 than for fibrinogen 1 (Figure 5, inset), but after that no differences in the rate or extent of cross-linking were found. In addition, the onset of α-polymer formation was delayed for fibrinogen 2, and the rate of α-polymer formation was slower than that of fibrinogen 1 (Figure 5). To explore these observations, we also compared fibrinogen or fibrin cross-linking by factor XIIIa and found no differences between the rate of γ-chain cross-linking of fibrinogens 1 and 2 (data not shown) or fibrins 1 and 2 (data not shown) throughout the course of the reaction. As in the cross-linking system in which thrombin was added (Figure 5), the rate of α-polymer formation was slower for fibrinogen 2 or fibrin 2 than for the respective fibrinogen 1 or fibrin 1 component (data not shown). Our findings are inconsistent with those of Moaddel et al,28 who reported more extensive cross-linking for fibrin 2.

Fibrinolysis

We have recently shown that thromboelastography is a reliable and sensitive means for measuring fibrinolysis (clot disintegration),58 thus substantiating a wide variety of techniques that have been used to measure fibrin degradation. We carried out lysis experiments in the thromboelastograph at several thrombin concentrations. At high thrombin concentrations (20 U/mL), there was little difference in the maximum amplitude (MA; the maximum strength or stiffness [shear modulus] of the formed clot) developed by either fibrin, no doubt because of the rapid conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin (Table 3). At lower thrombin concentrations, the maximum amplitude developed by fibrin 2 was higher than that of fibrin 1. At all thrombin concentrations tested, the slope of the lysis component of the TEG was always lower for fibrin 2, and the time to return to baseline (complete clot disintegration) was always longer for fibrin 2 than for fibrin 1 (Figure 6; Table 3). These results confirm those of several previous studies showing that fibrin 2 undergoes lysis more slowly than does fibrin 1.

Clot parameters derived from thromboelastography

. | Maximum amplitude, dyne/cm2 . | . | Lysis at 30 min, % . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thrombin, U/mL . | Fibrin 1 . | Fibrin 2 . | Fibrin 1 . | Fibrin 2 . | ||

| 20 | 23 | 22 | 88 | 68 | ||

| 2 | 13 | 18 | 90 | 68 | ||

| 1 | 6 | 15 | 87 | 70 | ||

. | Maximum amplitude, dyne/cm2 . | . | Lysis at 30 min, % . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thrombin, U/mL . | Fibrin 1 . | Fibrin 2 . | Fibrin 1 . | Fibrin 2 . | ||

| 20 | 23 | 22 | 88 | 68 | ||

| 2 | 13 | 18 | 90 | 68 | ||

| 1 | 6 | 15 | 87 | 70 | ||

Discussion

Fibrin 2 network

In the present study we carried out a comprehensive comparison of fibrins derived from fibrinogen 1 or fibrinogen 2 to determine the basis for some of the known functional differences between these 2 types of fibrin and to resolve certain existing discrepancies. We verified the observation29 that clots formed from fibrinogen 2 (γA-γ′) after the addition of thrombin produce a finer and more branched network than do fibrin clots formed from fibrinogen 1 (γA-γA). Interestingly, Collet et al30 found that fibrin clot networks formed from recombinant homodimeric γ′–containing fibrinogen (γ′-γ′) contained slightly thicker fibers than did those from fibrinogen 1. This seemingly paradoxic observation may be related to the homodimeric γ′ chain content of this fibrin; nevertheless, these clots, like those from heterodimeric fibrin 2 clots (this study and Falls and Farrell27 ) lysed more slowly than did fibrin formed from fibrinogen 1. In any case, we found that clot networks formed directly from fibrin 1 or fibrin 2 monomer solutions were similar in appearance, and in both cases the fibers were wider in diameter and less branched than those formed from fibrinogen 2 after thrombin addition. These findings suggested that differences between thrombin-treated fibrinogen 1 and fibrinogen 2 fibrin were related to the rate of fibrinopeptide release. Indeed, FPA release from fibrinogen 2 was slower than that from fibrinogen 1, as was FPB release. Consistent with these observations, fibrin intermediates lacking one FPA (α-profibrin) were generated more slowly from fibrinogen 2. Slower release of FPA from fibrinogen 2 provide a likely explanation for the thinner and more branched networks observed in fibrin 2, consistent with the results of Blombäck et al,59 who showed that slow FPA release leads to thinner fibrin matrices. It seems less likely that these differences were related to delayed FPB release, as was proposed by Cooper et al.29

Rate of factor XIII activation peptide cleavage by thrombin or Atroxin. Reaction was initiated by adding 0.5 U/mL thrombin (A) or 0.5 U/mL Atroxin (B) at the zero time point. Factor XIII plus fibrinogen 1 (□); factor XIII plus fibrinogen 2 (○); factor XIII alone (▴).

Rate of factor XIII activation peptide cleavage by thrombin or Atroxin. Reaction was initiated by adding 0.5 U/mL thrombin (A) or 0.5 U/mL Atroxin (B) at the zero time point. Factor XIII plus fibrinogen 1 (□); factor XIII plus fibrinogen 2 (○); factor XIII alone (▴).

Factor XIII activation and fibrin cross-linking

The accelerating effect of fibrin on factor XIII activation is widely recognized.16-21,60 We found that the accelerating effect of fibrin 1 on thrombin-mediated XIII activation was more prominent than it was with fibrin 2 at equivalent levels of factor XIII. In sharp contrast to these findings, Moaddel et al28 found that fibrin 2 accelerated factor XIII activation to a greater extent than did fibrin 1. We believe that their fibrinogen 2 preparation contained factor XIII, as do all chromatographically purified preparations of fibrinogen 2 that are not specifically processed to remove the enzyme.26 Its unrecognized presence in fibrinogen 2 probably increased the observed level of XIII activity in fibrin 2. The differences in activation peptide release are attributable to the allosteric effects of thrombin binding to the fibrin 2 γ′ sequence.

Rate of γ-dimer and α-polymer formation in fibrin 1 versus fibrin 2. Reaction was initiated by adding thrombin (0.5 U/mL, final) to factor XIII-containing (100 Loewy U/mL) fibrinogen 1 or fibrinogen 2 in TBS containing 5 mM CaCl2. Fibrin 1 γ-dimer (□); fibrin 2 γ-dimer (○); fibrin 1 α-polymer (▪); fibrin 2 α-polymer (○). Inset shows the first 1.5 minutes of cross-linking.

Rate of γ-dimer and α-polymer formation in fibrin 1 versus fibrin 2. Reaction was initiated by adding thrombin (0.5 U/mL, final) to factor XIII-containing (100 Loewy U/mL) fibrinogen 1 or fibrinogen 2 in TBS containing 5 mM CaCl2. Fibrin 1 γ-dimer (□); fibrin 2 γ-dimer (○); fibrin 1 α-polymer (▪); fibrin 2 α-polymer (○). Inset shows the first 1.5 minutes of cross-linking.

We also measured factor XIII activation peptide cleavage by Atroxin (Sigma), an enzyme that is able to cleave FPA from fibrinogen57 but that does not bind to the γ′ sequence. Although XIII activation by Atroxin was accelerated by the presence of fibrinogen 1 or 2, there were no differences between them with respect to the acceleratory effect. This last finding indicated that the observed rate differences between fibrin(ogen)s 1 and 2 in a thrombin-catalyzed system are related to thrombin binding to the γ′ sequence. Thrombin binding to the γ′ sequence may induce long-range conformational changes at the catalytic site of thrombin, as discussed in the next section, thereby reducing its ability to convert factor XIII to XIIIa.

Farrell's group27,28 also reported that fibrin 2 became more highly cross-linked by factor XIIIa than fibrin 1, including more extensive γ and α chain cross-linking, a conclusion with which we do not agree. We found instead that in a cross-linking system in which thrombin is added to a mixture of fibrinogen and factor XIII, the initial γ-chain cross-linking rate was slower for fibrin 2 than for fibrin 1, but after that early period there were no measurable differences in the rate or extent of cross-linking. Furthermore, in that same system, the onset and overall rate of α-polymer formation was slower for fibrin 2 than for fibrin 1. We also compared fibrinogen or fibrin cross-linking by factor XIIIa and found no differences between the rates of γ-chain cross-linking of fibrinogen 1 and 2 or fibrin 1 and 2 throughout the course of the reaction. We also found that α-polymer formation was slower for fibrinogen 2 or fibrin 2 than for the respective fibrinogen 1 or fibrin 1 component. We believe that the discrepancy between their results and ours is that their fibrinogen 2 preparations contained unaccounted for factor XIII.

Basis for delayed fibrinopeptide release and factor XIII activation

There is considerable evidence for exosite-dependent allosteric effects in thrombin. With respect to exosite 2 binding, thrombin catalytic site function was affected by binding of prothrombin fragment 2,61,62 a peptide fragment of prothrombin fragment 2 (sF2),62,63 a monoclonal antibody directed against an epitope in thrombin exosite 2,64 platelet glycoprotein 1b (GP1b),65 and DNA aptamer HD-22.66 Our present finding of prolongation of the thrombin clotting time or reduction of kcat/Km for S-2238 hydrolysis in the presence of YP γ′ 408-427 indicated that thrombin binding at the γ′ site had induced allosteric changes at the catalytic site and provided a likely explanation for the delayed release of FPA from fibrinogen 2, the delayed generation of α-profibrin, and the slower cleavage rate of the XIII activation peptide.

Thromboelastograms showing polymerization and tPA-mediated lysis of fibrinogen 1 or fibrinogen 2. Reaction mixtures contained fibrinogen (7 mg/mL) and lys-plasminogen (2.0 μM). Thrombin (2 U/mL, final) and tPA (0.93 nM, final) were added to initiate the reactions. (A) Fibrinogen 1. (B) Fibrinogen 2.

Thromboelastograms showing polymerization and tPA-mediated lysis of fibrinogen 1 or fibrinogen 2. Reaction mixtures contained fibrinogen (7 mg/mL) and lys-plasminogen (2.0 μM). Thrombin (2 U/mL, final) and tPA (0.93 nM, final) were added to initiate the reactions. (A) Fibrinogen 1. (B) Fibrinogen 2.

Clot lysis

Delayed clot lysis rates have been correlated with thinner fiber matrices34-36 and are consistent with our present finding of delayed disintegration (lysis) of fibrin 2 fiber networks. Our finding of slowed lysis of fibrin 2 agrees with those of Falls and Farrell27 and with Collet et al,30 though in the latter case the fibers in the homodimeric γ′-γ′ fibrin matrix were slightly wider than those formed from fibrin 1 (γA-γA). We have no attractive explanation for their observations on homodimeric γ′-γ′ fibrin compared with our own on heterodimeric fibrin 2, though they attributed the effect to more extensive γ-chain cross-linking, which we now know is unlikely to occur.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, July 7, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0240.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL70627 (M.W.M.) and HL49413, HL58141, and HL73813 (E.D.C.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank David A. Meh for contributions to fibrinolysis experiments.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal