Abstract

Phospholipase C-γ2 (PLC-γ2) is a key component of signal transduction in leukocytes. In natural killer (NK) cells, PLC-γ2 is pivotal for cellular cytotoxicity; however, it is not known which steps of the cytolytic machinery it regulates. We found that PLC-γ2-deficient NK cells formed conjugates with target cells and polarized the microtubule-organizing center, but failed to secrete cytotoxic granules, due to defective calcium mobilization. Consequently, cytotoxicity was completely abrogated in PLC-γ2-deficient cells, regardless of whether targets expressed NKG2D ligands, missed self major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I, or whether NK cells were stimulated with IL-2 and antibodies specific for NKR-P1C, CD16, CD244, Ly49D, and Ly49H. Defective secretion was specific to cytotoxic granules because release of IFN-γ on stimulation with IL-12 was normal. Plcg2-/- mice could not reject MHC class I-deficient lymphoma cells nor could they control CMV infection, but they effectively contained Listeria monocytogenes infection. Our results suggest that exocytosis of cytotoxic granules, but not cellular polarization toward targets, depends on intracellular calcium rise during NK cell cytotoxicity. In vivo, PLC-γ2 regulates selective facets of innate immunity because it is essential for NK cell responses to malignant and virally infected cells but not to bacterial infections.

Introduction

Natural killer (NK) cells are key players in innate immune responses to malignant and virus-infected cells, which they can kill spontaneously.1 They also secrete chemokines and cytokines that recruit and activate other cells of the innate and the adaptive immune system.2 Our understanding of the intracellular signals that regulate development of NK cells, as well as the innate responses to cancer and infection, is as yet limited and lags behind the knowledge of intracellular signaling leading to the development and activation of B and T cells.3 B and T cells are strictly dependent on the triggering of antigen-specific receptors for both lymphopoiesis and for the execution of effector functions. By contrast, NK cells develop under the dominant control of cytokine receptors4 and can be activated by a number of stimuli including tumor antigens, stress molecules, viral products, inflammatory cytokines, and adhesion molecules.5

Although NK cells express a set of signaling proteins that largely overlaps with those expressed in T cells, development of NK cells proceeds almost undisturbed in the absence of a variety of signaling proteins (including FYN,6 LCK,7 SYK and ZAP-70,8 VAV family members,9,10 or adapters such as LAT11 and SLP-7612 ) whose absence instead profoundly perturbs T-cell development. Furthermore, NK cell activation may be attained in the absence of any of these signaling components, although immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM)-mediated activation is impaired when both SYK and ZAP-70 are absent,8 or when the VAV1-RAC pathway is nonfunctional.9,13,14

Phosphatidylinositol (PI)-specific phospholipase C-γ (PLC-γ) enzymes (comprising PLC-γ1 and PLC-γ2) are indispensable components of signal transduction complexes downstream of a number of immune receptors including antigen-specific receptors and FcR in lymphocytes, platelets, mast cells, and macrophages.15 Once phosphorylated by tyrosine kinases, they are recruited to the membrane via their SH2 and PH domains and catalyze the cleavage of PI 4,5-bisphosphate (PI4,5P2) into inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and 1,2-diacyl-glycerol (DAG). IP3 induces the opening of intracellular calcium stores leading to a rise in intracellular calcium concentration, whereas DAG activates the protein kinase C (PKC) and the Ras pathways.15 PLC-γ1 is ubiquitously expressed, whereas PLC-γ2 is confined to hematopoietic lineages.15 The effect of PLC-γ1 deficiency has not been assessed in vivo because Plcg1-/- mice die in utero at day 8.5 of embryonic life.16 The absence of PLC-γ2 is compatible with embryonic development, although mice born with 2 mutated Plcg2 alleles are less frequent than the mendelian ratio expected from heterozygous parents. Plcg2-/- mice have decreased numbers of mature follicular and marginal zone B cells as well as faulty B-cell functions.17-19 In addition, they show defective signaling downstream of a number of immunoglobulin-like receptors in mast cells, platelets, and NK cells.17

Human NK cells express both PLC-γ1 and PLC-γ2,20 whereas mouse NK cells predominantly express PLC-γ2.21 ITAM-bearing receptors functionally couple with both isoforms, but activation initiated by NKG2D-DAP10 is dependent on PLC-γ2.22 In the mouse, PLC-γ2 appears to be essential and nonredundant for cellular cytotoxicity.17,21

We set out to study whether mouse NK cells require PLC-γ2-mediated signals in vivo and whether such signals are required during innate immunity to transplanted lymphoma cells, as well as to viral and bacterial infections. Our results suggest that, in contrast to the recurrent theme of molecular redundancy in NK cell signal transduction, PLC-γ2 is uniquely required for NK cells to develop cellular innate immunity to cancer and to viral infection but not to bacterial infections.

Materials and methods

Mice and hematopoietic chimeras

Mice lacking both recombinase activating gene (Rag) 2 and cytokine receptor common γ chain (Rag2-/-Ilrg-/-23 ) or PLC-γ2 (Plcg2-/-17 ) have been described previously. C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice were obtained from Janvier (Le Genest-Saint-Isle, France). Mice were kept at the Central Animal Facilities of the Pasteur Institute (Paris, France) and were used at 5 to 10 weeks of age. All protocols for animal experiments were reviewed by the Central Animal Facilities of the Pasteur Institute and were done in accordance with guidelines approved by the French Ministry of Agriculture. Some experiments were done with mice kept at the Small Animal Barrier Unit of the Babraham Institute (Cambridge, United Kingdom), according to United Kingdom Home Office guidelines. Hematopoietic chimeras were generated as described.23 Briefly, recipient Rag2-/-Ilrg-/- mice (C57BL/6 background) were irradiated with 600 rads from a cesium source and thereafter 2 to 4 × 106 fetal liver cells (E13.5-14.5) or 3 to 12 × 106 bone marrow cells from wild-type (WT) or Plcg2-/- mice (both on B10.D2 background) were injected intravenously in the retro-orbital sinus or in the lateral tail vein in 200 μL saline buffer as a source of donor hematopoietic stem cells. Chimeric mice were analyzed between 4 and 10 weeks after transfer. Chimeras are referred to as WT and Plcg2-/- mice throughout the paper. All mature lymphocytes in this setting are consistently from donor origin (Figure 7 presents an example). For some in vitro experiments cells were purified from young and healthy parental (nonchimeric) WT and Plcg2-/- mice. No obvious difference was noted between cells obtained from chimeras and cells obtained from the parental mice.

Isolation of lymphoid cells and flow cytometric analysis

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from bone marrow, spleen, peritoneal cavity, and liver and stained as described.9 Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) conjugated to FITC, PE, biotin, PerCP.Cy5, allophycocyanin (APC), or biotin specific for CD3, H-2Kb, NK1.1, and NKG2D (CX5) were obtained from Becton Dickinson (San Diego, CA) or eBioscience (San Diego, CA). The 1F8 antibody (specific for Ly49C/I/H) was a generous gift of Dr Michael Bennett (Dallas) and the 3D10 antibody (specific for Ly49H) was a generous gift of Dr Wayne Yokoyama (St. Louis). Biotinylated mAbs were revealed by streptavidin conjugated to various fluorochromes. Samples were analyzed using a FACScalibur flow cytometer and a CellQuest 3.3 (Becton Dickinson) or FlowJo 6.3 software. Prior to cytotoxicity assays or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), fresh splenocytes were first coated with rat mAbs specific for CD19 and TER-119 and then depleted of most B cells and erythrocytes by using goat anti-rat immunoglobulin beads (Ademtech, Pessac, France). Thereafter, cells were stained with mAbs specific for NK1.1 and CD3. NK1.1+CD3- NK cells were electronically sorted with a FACSstar plus or a Moflo (Cytomation, Fort Collins, CO). Alternatively, CD49b (DX5)+ cells were positively enriched to 70% to 80% purity with anti-CD49b beads and mini-magnetically activated cell sorting (MACS) separation. Purified cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 100 U/mL penicillin (all from Gibco, Grand Island, NY), and 5 × 10-5 M β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) in the presence of 1000 U/mL human recombinant IL-2 (rhIL-2; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), for 5 to 8 days. The purity of the sorted populations was reproducibly more than 95%.

Gene expression analysis

RNA was isolated from splenic NK cells (CD3-NK1.1+) using RNAble (Eurobio, Les Ulis, France) and cDNAs synthesized using avian myeloblastosis reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI), primed with random hexanucleotides and oligo-dT (Amersham Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using Taq platinum polymerase (Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom) and samples were amplified for 35 cycles at an annealing temperature of 60°C. The 5′-3′ primer sequences were as follows: HPRT forward: GCT GGT GAA AGG GAC CTC T; HPRT reverse: CAC AGG ACT AGA ACA ACA CCT GC; perforin forward, TCT CGC ATG TAC AGT TTT CGC CTG GTA; perforin reverse, TGT GAG CCC ATT CAG GGT CAG CTG; granzyme forward, GCC CAC AAC ATC AAA GA; granzyme reverse, CCC GAA AGG AAG CAC; NKG2A forward, CGA AGC AAA GGC ACA GA; NKG2A reverse, TGG GGA ATT TAC ACT TAC AAA; NKG2D forward, TCC TAT CAC TGG ATG GGA CTG GTC; NKG2D reverse, GGT TGT TGC TGA GAT GGG TAA TG; DAP10 forward, CTA GCT GCC TCT CTT CTC CTC TAC T; DAP10 reverse, CAT ACA AAC ACC ACC CCT ACA AT; DAP12 forward, GGC TCT GGA GCC CTC CTG GTG G; DAP12 reverse, CTG TGT GTT GAG GTC ACT GTA.

Perforin expression analysis

After culture in rhIL-2, cell suspensions containing 106 cells were put onto coverslips coated with poly-l-lysine, allowed to sediment for 5 minutes, then centrifuged at 47g for 1 minute, and fixed for 10 minutes at -20°C in methanol. Intracellular proteins were then stained by incubating cells in PBS 0.05% BSA, using monoclonal anti-perforin rat IgG2a (clone CB5.4; Alexis, London, United Kingdom) revealed by Alexa Fluor-488-coupled antirat mAbs (Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands). Confocal microscopy was carried out on a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope (Thornwood, NY). Detectors were set to detect an optimal signal below the saturation limits. Image sets to be compared were acquired during the same session and using the same acquisition settings. Fluorescence associated to clusters was quantified using Metamorph software (Universal Imaging, Downingtown, PA).

Cytotoxicity assays

A standard 4-hour 51Cr-release assay was used to measure NK cell cytolytic activity in vitro. Target cells (YAC-1, RMA, RMA-S, RMA-Rae1γ, Baf3, Baf3-m157, and P815) were labeled with 100 μCi (3.7 MBq) 51Cr (ICN Pharmaceutical, Costa Mesa, CA). Effector cells were either red cell-depleted fresh splenocytes (enriched for NK cells by passage on nylon wool columns or by 20 minutes of adherence on Petri dishes to remove most granulocytes and monocytes) or in vitro expanded cells after a culture period of 5 to 8 days in RPMI 1640 supplemented with rhIL-2. Prior to the assay, cells were stained with anti-NK1.1 and anti-CD3 mAb to quantify and adjust cell numbers so as to have in all samples equivalent numbers of specific subsets of effector cells (NK1.1+CD3- NK cells). For redirected antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (R-ADCC), rhIL-2-activated effector cells were incubated with 20 μg/mL mAb specific for NK1.1 (clone PK136), or Ly49H (3D10), Ly49D (4E5), CD16 (2.4G2), or CD244 (2B4), and, as negative control, TER-119 for 20 minutes at 4°C prior to the 4-hour 51Cr-release assay done using mastocytoma P815 (H-2d) target cells.

Radioactivity-free assay for tumor rejection in vivo

Tumor cell lines RMA and RMA-S were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10-5 M β-mercaptoethanol and 10% FCS, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 100 U/mL penicillin. Cells in exponential growth were harvested, counted, and labeled with 5 μM CFSE (Molecular Probes). Briefly, cells were resuspended in PBS, 2% FCS at 107 cells/mL and labeling was done at 37°C for 10 minutes. Such labeling was done to discriminate the MHC class I (H-2b+) RMA cells from the host cells (H-2b) resident in the peritoneal cavity of the chimeric mice. After being washed twice in RPMI 1640, 10% FCS, the cells were resuspended in appropriate volume of PBS, 2% FCS, mixed, and injected in the peritoneal cavity (2 × 105 RMA cells plus 4 × 105 RMA-S cells, 500μL/mouse) of WT and Plcg2-/- mice. Nonreconstituted Rag2-/-Ilrg-/- mice were also used as negative controls. An aliquot of the mixed cells was kept in culture. Forty-eight hours later mice were humanely killed and peritoneal cells were recovered. CFSE staining in combination with H-2b staining allowed discrimination of RMA cells (CFSE+ and H-2b+) from RMA-S cells (CFSE+ and H-2b-) and host cells (CFSE- and H-2b+ or CFSE- and H-2b-).

Conjugate formation

Purified NK cells activated for 5 to 7 days in rhIL-2 were labeled with 0.5 μM CFSE, washed, and mixed with a 1:1 ratio of YAC-1 targets (105 cells each) that had been labeled with 2 μM PKH26 red fluorescent (Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 minutes at room temperature. Cell mix was centrifuged at 100g for 5 minutes at 4°C and incubated for 1, 2, 5, and 10 minutes at 37°C. After gentle resuspension, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Conjugates could be readily detected as double positive for CFSE and PKH26. Controls were sham conjugates obtained by centrifuging and incubating under the same conditions differentially labeled (CFSE and PKH26) YAC-1 cells.

Calcium flux

Purified and rhIL-2-activated WT or Plcg2-/- NK cells were loaded with 2 μM INDO-1-am (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) for 45 minutes and subsequently coated with anti-NK1.1 (20 μg/mL) or left uncoated (negative controls). Analysis was done for 45 seconds to set the baseline levels of intracellular calcium. Acquisition was interrupted once to add cross-linking goat anti-mouse F(ab′)2 antibodies (Caltag, Burlingame, CA) and a second time to add 1 μg/mL ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were analyzed by Life Sciences Research LSR-FACS (Becton Dickinson).

MTOC polarization

Purified NK cells activated for 5 to 7 days in rhIL-2 were mixed for 15 minutes at 37°C with equal numbers of YAC-1 target cells labeled with CFSE. Mixed cells were then fixed with methanol and stained with rat antiperforin (clone CB5.4, Alexis, London, United Kingdom) and mouse anti-γ-tubulin (clone GTU-88; Sigma-Aldrich) followed by anti-rat rhodamine (Jackson ImmunoResearch, Cambridge, United Kingdom) and anti-mouse IgG-Cy5 (Amersham), respectively. A total of 184 WT and 215 Plcg2-/- NK cells forming conjugates with YAC-1 cells were counted to score microtubule-organizing center (MTOC) polarization. Each NK cell was arbitrarily divided in 4 sectors, and MTOC was considered polarized toward the target when it was localized in the sector facing the target (as illustrated in Figure 4). Because NK cells in rhIL-2 show nonspecific MTOC relocation, random polarization may be, under our conditions of analysis, up to 25%.

Degranulation

A recently described method24,25 was used, with minor modifications, to detect extracellular lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (CD107a), which marks degranulating cells. Briefly, CD49b+ MicroBead-selected fresh splenocytes (70%-80% NK1.1+CD3-) were incubated for 5 hours in the presence of anti-CD107a-FITC antibody and 50 μM monensin (Sigma-Aldrich), which was added after the first 1 hour), with or without YAC-1 targets (1:2 NK/target ratio), or with 50 ng/mL PMA and 1 μg/mL ionomycin (both from Sigma-Aldrich). Thereafter, cells were stained with anti-NK1.1, anti-CD3, and propidium iodide. CD107a+ cells were measured within NK1.1+CD3- live cells. In parallel, purified NK cells activated for 5 to 7 days in rhIL-2 were plated at 3 × 105 cells/well in anti-NK1.1-coated wells (20 μg/mL) or in wells coated with a mouse IgG2a isotype-matched control mAb in a final volume of 100 μL. After 4 hours of incubation, the specific esterase activity released in 50 μL cell-free supernatants was measured in 150 μL PBS containing 0.22 mM ethanol-dissolved 5,5′-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB; Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.2 mM ethanol-dissolved BLT (Na-benzyloxycarbonyl-l-lysine thiobenzol ester hydrochloride (Calbiochem), as previously described.9 Maximal release was obtained by measuring the esterase activity of NK cell lysates after 2 freeze-thaw cycles.

Cytokine production

NK1.1+CD3- NK cells were electronically sorted with a FACSstar plus or a Moflo from fresh spleen cell suspensions and cultured for 5 to 8 days in RPMI 1640 supplemented with rhIL-2. Tissue culture plates were coated with 20 μg/mL anti-NK1.1 mAbs diluted in bicarbonate solution, overnight at 4°C. NK cells (105 cells/well) were cultured for 48 hours in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS and rhIL-2 (1000 U/mL), in the presence of anti-NK1.1 mAb, or mouse rIL-12 (5 ng/mL; PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) or 50 ng/mL PMA and 1 μg/mL ionomycin (the latter 2 both from Sigma-Aldrich). The amount of IFN-γ released in the culture supernatants was determined by using the mouse IFN-γ-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit OptEIA (Becton Dickinson) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Infections with Listeria monocytogenes and MCMV

WT or Plcg2-/- mice were either infected intragastrically with 5 × 108Listeria monocytogenes (strain L028) as previously described26 or infected intraperitoneally with 5 to 10 × 103 plaque-forming units (PFUs) MCMV (strain Smith, salivary gland preparation). Spleen and liver bacterial burdens were determined at day 4 as previously described using a colony-forming unit (CFU) assay.26 Spleen and liver viral titers were determined at day 3 with a PFU assay using mouse embryonic fibroblasts as described.27 Nonreconstituted Rag2-/-Ilrg-/- mice were used as negative controls and reference strains C57BL/6 and BALB/c were used as standard controls for viral infections.

Statistics

Data were analyzed with Microsoft Excel software applying the 2-tailed Student t test. The null hypothesis was rejected and differences assumed significant when P was less than .05.

Results

NK cell development in the absence of PLC-γ2

Because PLC-γ2-deficient mice show several defects in the hematopoietic lineages, we set out to assess the cell autonomous effect of PLC-γ2 deficiency in the lymphoid populations. We generated hematopoietic chimeras by injecting PLC-γ2-deficient (Plcg2-/-) and control (wild-type littermate, WT) fetal liver cells into alymphoid mice lacking RAG-2 and the common cytokine receptor γ chain (Rag2-/-Ilrg-/-23 ). At least 4 weeks after reconstitutions, lymphoid development was analyzed in the WT and Plcg2-/- chimeras, which will be referred to as WT and Plcg2-/- mice, respectively. Consistent with previous reports, B-but not T-cell lymphopoiesis was defective in the absence of PLC-γ2 (data not shown and Wang et al,17 Hashimoto et al,18 and Bell et al19 ). CD3-NK1.1+ NK cell counts were equivalent in spleen, liver, peritoneal cavity, and bone marrow of WT and Plcg2-/- mice (Figure 1A and data not shown), suggesting that NK cell generation is not disrupted by the absence of PLC-γ2.

NK cells develop in the absence of PLC-γ2. (A) Representative FACS profile of WT and Plcg2-/- splenocytes gated on the lymphoid population. Numbers in plots represent means of NK counts in 19 WT and 19 Plcg2-/- individual mice. (B) Transcripts of activating receptors, adaptors, and effector molecules in IL-2-activated splenocytes (lymphokine-activated killer [LAK] cells), and resting CD3-NK1.1+ purified NK cells from WT or Plcg2-/- mice. (C) Fresh splenocytes were stained with the indicated markers. Gated CD3- NK1.1+ cells are shown. Percentages in the histograms indicate cells staining positive for the specific marker. (D) Mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) is shown for the indicated markers expressed on gated CD3-NK1.1+Plcg2-/- splenocytes. Bars represent percentage values of MFI found on gated CD3-NK1.1+ WT splenocytes.

NK cells develop in the absence of PLC-γ2. (A) Representative FACS profile of WT and Plcg2-/- splenocytes gated on the lymphoid population. Numbers in plots represent means of NK counts in 19 WT and 19 Plcg2-/- individual mice. (B) Transcripts of activating receptors, adaptors, and effector molecules in IL-2-activated splenocytes (lymphokine-activated killer [LAK] cells), and resting CD3-NK1.1+ purified NK cells from WT or Plcg2-/- mice. (C) Fresh splenocytes were stained with the indicated markers. Gated CD3- NK1.1+ cells are shown. Percentages in the histograms indicate cells staining positive for the specific marker. (D) Mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) is shown for the indicated markers expressed on gated CD3-NK1.1+Plcg2-/- splenocytes. Bars represent percentage values of MFI found on gated CD3-NK1.1+ WT splenocytes.

Transcripts of activating receptors, crucial adaptors, and effector molecules were all expressed in mutant NK cells (Figure 1B), suggesting gene expression during differentiation was regulated normally. Nevertheless, the NK cell receptor repertoire showed clear abnormalities both in terms of percentages of subsets expressing specific markers (Figure 1C; Table 1), and in terms of expression intensity (Figure 1D). The selective defect in receptor expression did not seem to arrest NK development because late maturation markers CD11b and CD43 were expressed normally in mutant NK cells (Figure 1C).

Expression of NK cell markers

. | WT, % . | Plcg2–/–, % . |

|---|---|---|

| CD16 | 99 ± 1 | 99 ± 1 |

| CD244 | 99 ± 1 | 99 ± 1 |

| CD69 | 29 ± 8 | 34 ± 24 |

| Ly49A | 2 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 |

| Ly49C/I | 31 ± 11 | 9 ± 5* |

| Ly49D | 13 ± 7 | 7 ± 3* |

| Ly49G2 | 41 ± 5 | 5 ± 1* |

| Ly49H+C/I– | 31 ± 9 | 29 ± 4 |

| NK1.1 | 99 ± 1 | 99 ± 1 |

| NKG2A/C/E | 76 ± 6 | 64 ± 5* |

. | WT, % . | Plcg2–/–, % . |

|---|---|---|

| CD16 | 99 ± 1 | 99 ± 1 |

| CD244 | 99 ± 1 | 99 ± 1 |

| CD69 | 29 ± 8 | 34 ± 24 |

| Ly49A | 2 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 |

| Ly49C/I | 31 ± 11 | 9 ± 5* |

| Ly49D | 13 ± 7 | 7 ± 3* |

| Ly49G2 | 41 ± 5 | 5 ± 1* |

| Ly49H+C/I– | 31 ± 9 | 29 ± 4 |

| NK1.1 | 99 ± 1 | 99 ± 1 |

| NKG2A/C/E | 76 ± 6 | 64 ± 5* |

Percent of cells expressing the indicated markers on gated CD3–NK1.1+ cells from spleens of individual hematopoietic chimeras 4 to 7 weeks after reconstitution with WT or Plcg2–/– fetal liver cells (6-9 mice/group were analyzed).

P < .05

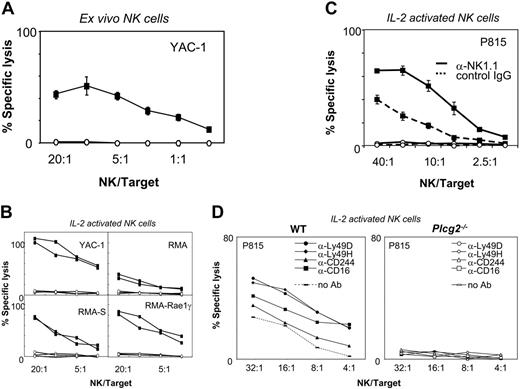

Lack of NK cell cytotoxicity in the absence of PLC-γ2

Cellular cytotoxicity is the main effector function by which NK cells rapidly kill tumor and infected cells that have lost expression of MHC class I or acquired expression of stress-induced ligands, such as those that bind NKG2D. NK cell activity was undetectable in fresh Plcg2-/- cells (Figure 2A) and could not be induced by cytokine prestimulation nor by receptor cross-linking (Figure 2B-C). Targets included the YAC-1 thymoma (expressing NKG2D ligands and low levels of MHC class I molecules), the RMA lymphoma, its TAP-deficient RMA-S variant, and its transfectant expressing the NKG2D ligand RAE-1γ. In all conditions, NK cell cytotoxicity was completely abrogated in Plcg2-/- NK cells. Mutant NK cells also failed to kill FcR+ P815 mastocytoma cells when NKR-P1C (also known as NK1.1), or other activating receptors, including Ly49D, Ly49H, CD16, or 2B4, were specifically stimulated (Figure 2D).

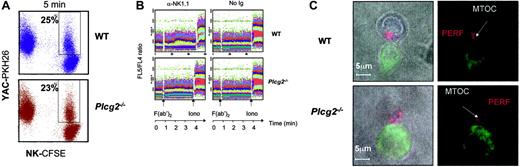

Mechanisms of defective NK cytotoxicity

To dissect the cellular defect responsible for the complete absence of killing in Plcg2-/- NK cells, we set out to evaluate the different events required for cytolytic function. First, we assessed the ability of NK cells to form conjugates with susceptible target cells. Plcg2-/- NK cells were able to form conjugates with YAC-1 cells. In 3 independent experiments using IL-2-activated NK cells, we measured comparable fractions of mutant and WT NK cells forming conjugates with targets at 1, 2, 5, and 10 minutes (Figure 3A and data not shown).

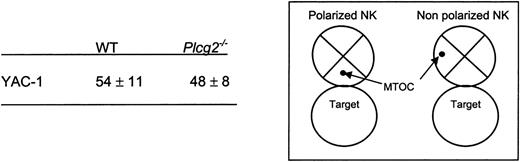

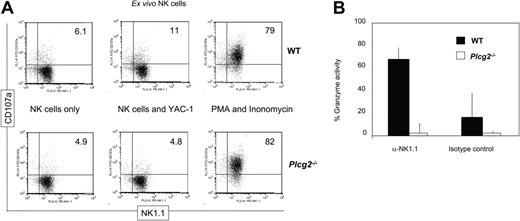

PLC-γ2 is pivotal for the mobilization of intracellular calcium in B but not T lymphocytes,18 due to differential expression of PLC-γ1 in T cells. NK cells express both enzymes, although mouse NK cells predominantly express PLC-γ2.20-22 We found that virtually no increase in cytoplasmic calcium concentration followed NK1.1 cross-linking in Plcg2-/- NK cells (Figure 3B), suggesting that PLC-γ2 plays an essential and nonredundant role in this function. Calcium influx is an early event during perforin-mediated cytotoxicity. However, it is not clear in cytotoxic lymphocytes whether calcium influx regulates the reorientation or the degranulation of the cytotoxic granules or whether it is required for both events.28,29 Confocal microscopy analysis of NK cells conjugated with tumor targets revealed that mutant cells could polarize the cytotoxic granules and the MTOC toward the target (Figure 3C). We then attempted to quantify polarization of perforin. Despite extensive analysis, and in contrast to what is usually found in cytotoxic T cells, we have noticed that mouse primary NK cells do not form tight clusters of cytotoxic granules toward the targets, making it difficult to quantify polarization. For this reason we used the location of the MTOC as a marker of cellular polarization. The frequency of mutant NK cells polarized toward YAC-1 targets was similar to that of WT NK cells (Figure 4). On the contrary, target-induced degranulation was blocked in mutant NK cells. A new FACS-based assay that specifically detects degranulating cells by virtue of CD107a expression revealed only background staining in mutant cells (Figure 5A). In addition, a classical degranulation assay revealed lack of degranulation following anti-NK1.1 stimulation in PLC-γ2-deficient NK cells (Figure 5B). Therefore, MTOC polarization appears uncoupled from PLC-γ2-mediated calcium response, but PLC-γ2 is absolutely required to regulate degranulation of cytotoxic granules.

Key role for PLC-γ2 in NK cell cytotoxicity. (A) Fresh splenocytes from WT (▪) but not Plcg2-/- (○) mice were spontaneously cytotoxic toward YAC-1 cells at the indicated NK/target ratios. Data are the mean ± SD of triplicates from one representative of 4 independent experiments. (B) IL-2-activated splenocytes from WT (▪, 2 individual mice) but not Plcg2-/- mice (○, 2 individual mice) were cytotoxic toward YAC-1, RMA, RMA-S, and RMA-Rae1γ cells at the indicated NK/target ratios. Data are the mean ± SD of triplicates of one representative of 5 independent experiments. (C) IL-2-activated CD3-NK1.1+ purified NK cells were coated with anti-NK1.1 and tested in redirected ADCC against P815 targets. WT (▪) but not Plcg2-/- (○) NK cells were cytotoxic toward P815 at the indicated NK/target ratios. Data are the mean ± SD of 2 to 4 experiments. (D) Cells were prepared as described and coated with the indicated antibodies prior to redirected ADCC toward P815 targets. Data are from one representative of 2 independent experiments that gave similar results. In all experiments, NK/target ratios were calculated based on actual CD3-NK1.1+ NK cell numbers, as measured by cell counts and flow cytometry prior to the assays.

Key role for PLC-γ2 in NK cell cytotoxicity. (A) Fresh splenocytes from WT (▪) but not Plcg2-/- (○) mice were spontaneously cytotoxic toward YAC-1 cells at the indicated NK/target ratios. Data are the mean ± SD of triplicates from one representative of 4 independent experiments. (B) IL-2-activated splenocytes from WT (▪, 2 individual mice) but not Plcg2-/- mice (○, 2 individual mice) were cytotoxic toward YAC-1, RMA, RMA-S, and RMA-Rae1γ cells at the indicated NK/target ratios. Data are the mean ± SD of triplicates of one representative of 5 independent experiments. (C) IL-2-activated CD3-NK1.1+ purified NK cells were coated with anti-NK1.1 and tested in redirected ADCC against P815 targets. WT (▪) but not Plcg2-/- (○) NK cells were cytotoxic toward P815 at the indicated NK/target ratios. Data are the mean ± SD of 2 to 4 experiments. (D) Cells were prepared as described and coated with the indicated antibodies prior to redirected ADCC toward P815 targets. Data are from one representative of 2 independent experiments that gave similar results. In all experiments, NK/target ratios were calculated based on actual CD3-NK1.1+ NK cell numbers, as measured by cell counts and flow cytometry prior to the assays.

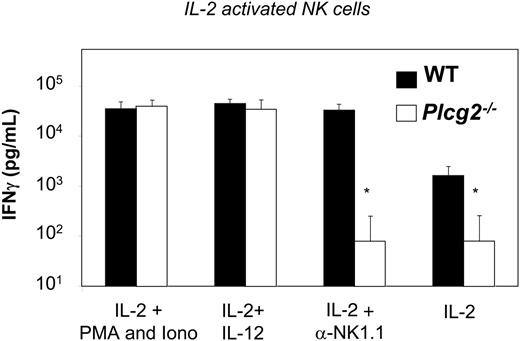

Distinct pathways for IFN-γ production

We have previously shown that separate pathways regulate cytotoxicity and cytokine production downstream of specific NK receptors.9 To assess whether PLC-γ2 regulates also secretion of cytokines by NK cells, we measured IFN-γ release by IL-2-expanded purified NK cells. Mutant NK cells expanded effectively in IL-2 cultures (data not shown), suggesting that the response to this cytokine was normal. Yet, the basal level of IFN-γ production was significantly reduced in PLC-γ2-deficient NK cells, and, in contrast to WT cells, stimulation with anti-NK1.1 resulted in no augmentation of IFN-γ release (Figure 6). These results suggest that the signaling pathways leading to IFN-γ production downstream of the low-affinity IL-2βγ receptor (mouse NK cells cultured in IL-2 do not express detectable levels of high-affinity IL-2Rα30 ) and of NK1.1 both depend on PLC-γ2. However, IFN-γ production in response to IL-12, as well as to phorbol ester and calcium ionophore, was normal in mutant NK cells (Figure 6). This suggests that the IL-12R/JAK2/STAT4 and IL-2Rβγ/JAK1/3/STAT5 pathways leading to Ifnγ gene transcription have differential requirements for PLC-γ2-dependent signals in NK cells. Furthermore, these results show that release of IFN-γ is intrinsically normal in Plcg2-/- NK cells. Thus, PLC-γ2 is not an absolute requirement for cytokine gene transcription and cytokine secretion in NK cells.

PLC-γ2 is required for calcium mobilization, but not for conjugate formation or MTOC reorientation. (A) CFSE-labeled WT and Plcg2-/- NK cells were coincubated at a 1:1 ratio with PKH-26-labeled YAC-1 target cells for 1, 2, 5, and 10 minutes at 37°C. Percentages of NK cells conjugated with targets were measured by flow cytometry. Data at 5 minutes from one representative experiment of 3 independent experiments is shown. (B) Anti-NK1.1-coated WT NK cells but not Plcg2-/- NK cells responded to cross-linking secondary antibody with an increase of intracellular calcium. The right panel shows negative control data obtained with NK cells that were left uncoated. (C) WT and Plcg2-/- NK cells were able to polarize the MTOC and the cytotoxic granules toward CFSE-labeled YAC-1 target cells. The blue staining identifies γ-tubulin (MTOC), whereas the red staining identifies perforin. One representative 2-dimensional reconstruction of the xy projection of a NK/YAC conjugate is represented for both genotypes. Confocal microscopy was carried out using a 63×/1.4 NA oil objective lens. Images were processed using Adobe Photoshop 5.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

PLC-γ2 is required for calcium mobilization, but not for conjugate formation or MTOC reorientation. (A) CFSE-labeled WT and Plcg2-/- NK cells were coincubated at a 1:1 ratio with PKH-26-labeled YAC-1 target cells for 1, 2, 5, and 10 minutes at 37°C. Percentages of NK cells conjugated with targets were measured by flow cytometry. Data at 5 minutes from one representative experiment of 3 independent experiments is shown. (B) Anti-NK1.1-coated WT NK cells but not Plcg2-/- NK cells responded to cross-linking secondary antibody with an increase of intracellular calcium. The right panel shows negative control data obtained with NK cells that were left uncoated. (C) WT and Plcg2-/- NK cells were able to polarize the MTOC and the cytotoxic granules toward CFSE-labeled YAC-1 target cells. The blue staining identifies γ-tubulin (MTOC), whereas the red staining identifies perforin. One representative 2-dimensional reconstruction of the xy projection of a NK/YAC conjugate is represented for both genotypes. Confocal microscopy was carried out using a 63×/1.4 NA oil objective lens. Images were processed using Adobe Photoshop 5.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

MTOC polarization in NK cells conjugated with target cells. Individual cell conjugates were scored polarized or not as shown in the insert. Numbers are percentages of conjugated NK cells that show MTOC relocation in the cell quarter facing the target. Data are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments including a total of more than 180 cell conjugates.

MTOC polarization in NK cells conjugated with target cells. Individual cell conjugates were scored polarized or not as shown in the insert. Numbers are percentages of conjugated NK cells that show MTOC relocation in the cell quarter facing the target. Data are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments including a total of more than 180 cell conjugates.

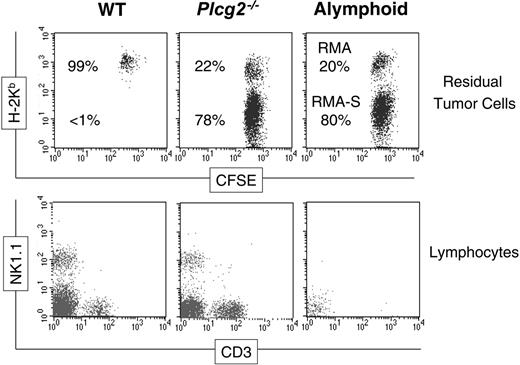

Compromised innate immunity to malignancy and CMV but not L monocytogenes in PLC-γ2-deficient mice

NK cells are key players in innate immunity to cancer and infections.31 To appreciate the biological relevance of PLC-γ2 to these functions in the whole animal, we assessed innate immune responses using various in vivo models.

Our tumor rejection assay allows us to test the ability of NK cells to discriminate susceptible (ie, RMA-S) and resistant (ie, RMA) target cells and to rapidly eliminate the susceptible ones.32 When injected into control alymphoid mice (Rag2-/-Ilrg-/-), neither RMA-S nor RMA cells could be rejected, demonstrated by the fact that both cell types could be recovered in the peritoneal exudate at the end of the assay. In contrast, WT mice were capable of readily rejecting most RMA-S cells, thus inverting the percentages of the 2 cell types (Figure 7). The pattern of tumor cells recovered from Plcg2-/- mice was very similar to that from alymphoid mice, despite the presence of NK cells in the peritoneal cavity (Figure 7). This result shows that PLC-γ2 is essential for rejection of class I-deficient RMA-S cells in vivo.

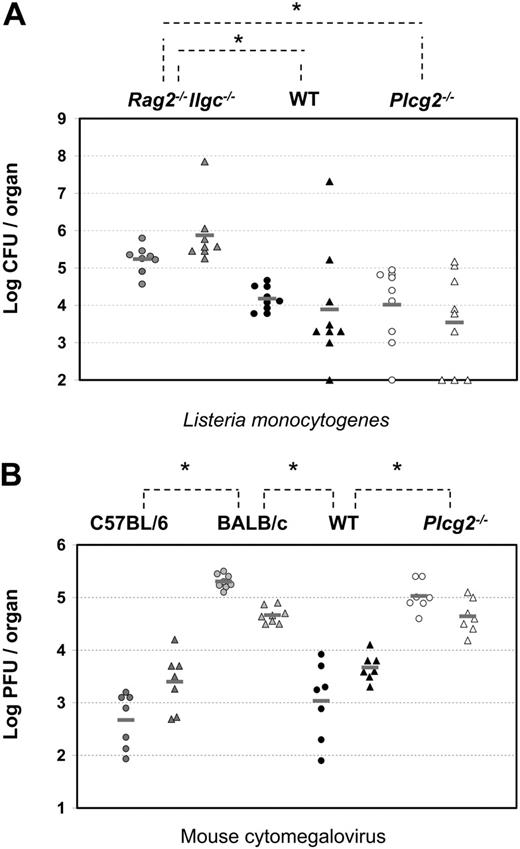

NK cells are thought to be critical sources of IFN-γ during early immune responses to L monocytogenes33 and, although the specific receptors involved are not characterized, cytokine receptors such as IL-12R are most likely dominant. Groups of alymphoid (Rag2-/-Ilrg-/-), WT, and Plcg2-/- mice were infected by intragastric inoculation of L monocytogenes. After 4 days, splenic and hepatic titers of L monocytogenes were measured. As expected, high bacterial burden was found in the spleens and livers of alymphoid Rag2-/-Ilrg-/- mice (Figure 8A). Significantly lower burdens were detected in the organs of WT as well as Plcγ2-/- mice, despite wide variations among individual mice. These results suggest that Plcg2-/- NK cells could mount protective responses against intracellular bacteria.

At variance with the L monocytogenes model, innate immunity to MCMV is controlled by a well-defined receptor-ligand system involving the NK-activating receptor Ly49H and the virally encoded glycoprotein m157.34,35 Such interaction triggers NK cell cytotoxicity, which is, in turn, required to control viral replication. Although perforin is the crucial effector molecule in the spleen, IFN-γ appears to be the effector molecule required in the liver.36 Therefore, viral titers in the spleens and livers of Ly49H-expressing mice (C57BL/6 and related strains like B10.D2, which we have used in this study) are 103- to 104- and 10- to 20-fold lower, respectively, than those of Ly49H- mice, such as BALB/c mice (Figure 8B). Despite expressing normal percentages of Ly49H+ NK cells (Table 1), Plcg2-/- mice were susceptible to MCMV infection and showed viral titers that were as high as susceptible BALB/c mice in both the spleen and liver (Figure 8B). Consistent with data shown in Figure 2D, where PLC-γ2-deficient NK cells did not respond to Ly49H stimulation, they also failed to kill m157-expressing Baf3 tumor cells (data not shown). These results show that PLC-γ2 is absolutely required for innate immunity to MCMV both in the spleen and liver.

Discussion

NK cells usually express more than one member of the same family of signaling molecules, therefore making it plausible that a functional redundancy accounts for lack of a specific NK cell trait in various KO mice.5 Also, with a large number of cell surface receptors that can trigger them, NK cells have multiple choices for activation.37 PLC-γ2 regulates calcium responses and cellular cytotoxicity38 and previous in vitro studies have shown defective but not totally abolished cytotoxicity in Plcg2-/- mice, leaving open the possibility that PLC-γ1 partially compensates for the absence of PLC-γ2.17 Nonetheless, precisely how the absence of PLC-γ2 causes defective cytotoxicity is not known and the biological relevance of this enzyme to NK cell development and immune responses in vivo has not been extensively addressed before. Human ITAM-bearing activating NK receptors can functionally couple with either PLC-γ1 or PLC-γ2, whereas DAP10-associated NKG2D selectively requires PLC-γ2.22 During the preparation of this manuscript, Tassi et al21 have published data demonstrating that PLC-γ2 is pivotal downstream of multiple mouse NK-activating receptors. These 2 recent studies emphasize the functional redundancy as well as subtle, but important, differences between human and mouse NK cells.

PLC-γ2 is a key regulator of degranulation. (A) Freshly DX5-enriched NK cells (70%-80% purity) were incubated for 5 hours, in the presence of anti-CD107a, with nothing, YAC-1 targets, or PMA and ionomycin, as indicated. Only cells that have degranulated expose CD107a on the cell surface. Target cells induced degranulation in WT but not Plcg2-/- NK cells. (B) WT (▪) and Plcg2-/- (□) NK cells were stimulated with anti-NK1.1 mAb or isotype-matched control and after 4 hours the specific esterase activity was measured by BLT-colorimetric assay. Maximal release in NK cell lysates obtained after freeze-thaw cycles was similar in WT and Plcg2-/- NK cells (not shown). Data are means ± SD of 2 independent experiments, including a total of 4 individual mice per group.

PLC-γ2 is a key regulator of degranulation. (A) Freshly DX5-enriched NK cells (70%-80% purity) were incubated for 5 hours, in the presence of anti-CD107a, with nothing, YAC-1 targets, or PMA and ionomycin, as indicated. Only cells that have degranulated expose CD107a on the cell surface. Target cells induced degranulation in WT but not Plcg2-/- NK cells. (B) WT (▪) and Plcg2-/- (□) NK cells were stimulated with anti-NK1.1 mAb or isotype-matched control and after 4 hours the specific esterase activity was measured by BLT-colorimetric assay. Maximal release in NK cell lysates obtained after freeze-thaw cycles was similar in WT and Plcg2-/- NK cells (not shown). Data are means ± SD of 2 independent experiments, including a total of 4 individual mice per group.

PLC-γ2 is required for NK1.1-initiated, but not for IL-12-initiated, IFN-γ production. WT (▪) and Plcg2-/- (□) NK cells were stimulated with the indicated stimuli. IFN-γ in the supernatant was quantified 48 hours later. Data are means ± SD of 6 to 8 experiments.

PLC-γ2 is required for NK1.1-initiated, but not for IL-12-initiated, IFN-γ production. WT (▪) and Plcg2-/- (□) NK cells were stimulated with the indicated stimuli. IFN-γ in the supernatant was quantified 48 hours later. Data are means ± SD of 6 to 8 experiments.

In contrast to the recurrent theme of functional redundancy among signal transduction proteins in NK cell biology, our results show that PLC-γ2 regulates unique signals required for mobilizing intracellular calcium and secreting cytotoxic granules. On the other hand, formation of conjugates with target cells, polarization of the MTOC toward the target, and IFN-γ production in response to IL-12 can progress without PLC-γ2. Consequently, the absence of PLC-γ2 totally compromises innate immunity to CMV and transplanted lymphoma cells, yet PLC-γ2-independent IFN-γ production in response to IL-12 leads to effective innate immunity to listeriosis. Most likely, IFN-γ production initiated by IL-12 or other PLC-γ2-independent stimuli in NK cells is sufficient to activate effector responses in macrophages that, in turn, destroy the bacteria. NK cells are the major cellular effectors within innate immunity to MCMV. Cellular cytotoxicity and IFN-γ contribute to the control of viral replication in infected cells.31,34,35 Elegant experiments have suggested that cellular cytotoxicity is the major mechanism of protection against MCMV in the spleen, whereas IFN-γ is predominantly required in the liver.36 Perforin-deficient mice showed high splenic titers, but their hepatic titers were significantly lower than those of NK cell-depleted mice and those of Ifnγr-/- mice, suggesting that IFN-γ produced by NK cells could control viral replication in the liver but not the spleen.36 Our results suggest that PLC-γ2-independent pathways of IFN-γ production (such as that induced by IL-12, for example) are not sufficient to control viral replication in the liver, where receptor-induced IFN-γ production (ie, Ly49H-induced) is most likely necessary.

Compromised antitumor immunity in PLC-γ2-deficient mice. CFSE-labeled RMA cells and MHC class I-deficient RMA-S cells were coinjected intraperitoneally into 3 groups of mice and 48 hours later the peritoneal cells were stained with anti-H-2Kb (top row) or CD3 and NK1.1 (bottom row). Essentially only H-2Kb+ RMA cells were recovered from WT mice, H-2Kb- RMA-S cells being rejected by WT NK cells. Both types of tumor cells were recovered from Plcg2-/- mice as well as from alymphoid Rag2-/-Ilrg-/- mice, suggesting that RMA-S cells were not cleared. The bottom row shows that NK cells are present in the peritoneal cavity of mutant mice. Data are from one individual mouse/group representative of 6 to 10 mice/group analyzed in 2 independent experiments.

Compromised antitumor immunity in PLC-γ2-deficient mice. CFSE-labeled RMA cells and MHC class I-deficient RMA-S cells were coinjected intraperitoneally into 3 groups of mice and 48 hours later the peritoneal cells were stained with anti-H-2Kb (top row) or CD3 and NK1.1 (bottom row). Essentially only H-2Kb+ RMA cells were recovered from WT mice, H-2Kb- RMA-S cells being rejected by WT NK cells. Both types of tumor cells were recovered from Plcg2-/- mice as well as from alymphoid Rag2-/-Ilrg-/- mice, suggesting that RMA-S cells were not cleared. The bottom row shows that NK cells are present in the peritoneal cavity of mutant mice. Data are from one individual mouse/group representative of 6 to 10 mice/group analyzed in 2 independent experiments.

Compromised innate immunity to viral, not bacterial, infections in PLC-γ2-deficient mice. (A) Four days after intragastric injection of 5 × 108 CFUs L monocytogenes per mouse, bacterial burdens were quantified by colony assay in spleen (circles) and liver (triangles) of alymphoid Rag2-/-Ilrg-/- mice (gray symbols, n = 8), Plcg2-/- mice (open symbols, n = 9), and WT mice (black symbols, n = 9). Data are pooled from 3 independent experiments. *WT versus Rag2-/-Ilrg-/-P < .001 for spleen and P = .006 for liver; Plcg2-/- versus Rag2-/-Ilrg-/-P = .006 for spleen and P < .001 for liver. (B) Three days after intraperitoneal injection of 5 to 10 × 103 PFUs MCMV/mouse, virus titers were quantified by plaque assay in spleen (circles) and liver (triangles) of C57BL/6 (dark gray symbols, n = 7), BALB/c (light gray symbols, n = 8) mice, Plcg2-/- mice (open symbols, n = 7), and WT mice (black symbols, n = 7). Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments. Bars represent the mean value of each group of mice. *C57BL/6 versus BALB/c P < .001 for spleen and P < .001 for liver; WT versus BALB/c P < .001 for spleen and P < .001 for liver; and WT versus Plcg2-/-P < .001 for spleen and P < .001 for liver.

Compromised innate immunity to viral, not bacterial, infections in PLC-γ2-deficient mice. (A) Four days after intragastric injection of 5 × 108 CFUs L monocytogenes per mouse, bacterial burdens were quantified by colony assay in spleen (circles) and liver (triangles) of alymphoid Rag2-/-Ilrg-/- mice (gray symbols, n = 8), Plcg2-/- mice (open symbols, n = 9), and WT mice (black symbols, n = 9). Data are pooled from 3 independent experiments. *WT versus Rag2-/-Ilrg-/-P < .001 for spleen and P = .006 for liver; Plcg2-/- versus Rag2-/-Ilrg-/-P = .006 for spleen and P < .001 for liver. (B) Three days after intraperitoneal injection of 5 to 10 × 103 PFUs MCMV/mouse, virus titers were quantified by plaque assay in spleen (circles) and liver (triangles) of C57BL/6 (dark gray symbols, n = 7), BALB/c (light gray symbols, n = 8) mice, Plcg2-/- mice (open symbols, n = 7), and WT mice (black symbols, n = 7). Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments. Bars represent the mean value of each group of mice. *C57BL/6 versus BALB/c P < .001 for spleen and P < .001 for liver; WT versus BALB/c P < .001 for spleen and P < .001 for liver; and WT versus Plcg2-/-P < .001 for spleen and P < .001 for liver.

Cellular cytotoxicity is the end point of a series of intracellular responses following conjugate formation with a susceptible target and subsequent receptor engagement by specific activating ligands. These responses include rearrangement of the cytoskeleton, mobilization of the MTOC and cytotoxic granules and, finally, polarized exocytosis. The calcium response is a key component of perforin-mediated cellular cytotoxicity.39,40 In which of these cellular responses calcium is involved is not clear. It was originally shown that calcium influx is required for the reorientation of the killer cell's Golgi apparatus and MTOC toward the target,28 whereas another report suggested that calcium flux does not direct granule reorientation in cytotoxic T cells.29 Our results show that in the absence of a normal calcium response in PLC-γ2-deficient NK cells, the MTOC can be polarized toward the target. By contrast, the secretion of cytotoxic granules is totally blocked in PLC-γ2-deficient NK cells. Therefore, PLC-γ2 does not seem to be essential for the reorientation of the MTOC and it rather appears to be an absolute requirement for degranulation.

The signal transduction pathways leading to cellular cytotoxicity are being deciphered37 and we may be able to draw a picture of the minimal requirements. Depending on the cell surface receptor engaged, and following activation of one of the SRC protein tyrosine kinases, the SYK/ZAP-70 or the PI3-K or both pathways are induced.32,41 Subsequently, these 2 pathways converge on members of the VAV family and on PLC-γ2. Although both VAV-1 and PLC-γ2 regulate NK cytotoxicity, they may control different steps along the pathways leading to cytotoxicity. PLC-γ2 but not VAV-1 is required for a normal calcium response on NK receptor stimulation. By contrast, VAV-1 and its effector RAC-1, but not PLC-γ2, are required for cellular polarization.9,13,14 One possible scenario is that VAV and its effectors regulate mobilization of the granules toward the target, whereas PLC-γ2 is required to relay the early signaling event of elevation in intracellular calcium concentration to the latest step of the cytolytic process, that is, the secretion of cytotoxic granules.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, October 4, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2428.

Supported by Institut Pasteur, INSERM, and Franco-British Partnership ALLIANCE/EGIDE Programme. A.C. is supported by a fellowship from Ligue National Contre le Cancer (LNCC). F.C.'s team is supported by “Equipe Labellisé LNCC” at the Pasteur Institute and by a Core Strategic Grant at the Babraham Institute.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We would like to thank J. Ihle for the Plcg2-/- mice; L. L. Lanier, G. de St-Basile, M. Bennett W. Yokoyama, and S. Vidal for reagents; A-M. Balazuc and A. Louise for cell sorting; E. Perret, V. Das, G. Bossi, and G. Griffiths for suggestions and use of confocal imaging; E. Corcuff and O. Richard-Le Goff for skillful technical assistance; J. Caraux, G. Butcher, C. A. Vosshenrich, and J. P. Di Santo for critically reading the manuscript, and the staffs at the Animal Facilities of Institut Pasteur and the Babraham Institute.

![Figure 1. NK cells develop in the absence of PLC-γ2. (A) Representative FACS profile of WT and Plcg2-/- splenocytes gated on the lymphoid population. Numbers in plots represent means of NK counts in 19 WT and 19 Plcg2-/- individual mice. (B) Transcripts of activating receptors, adaptors, and effector molecules in IL-2-activated splenocytes (lymphokine-activated killer [LAK] cells), and resting CD3-NK1.1+ purified NK cells from WT or Plcg2-/- mice. (C) Fresh splenocytes were stained with the indicated markers. Gated CD3- NK1.1+ cells are shown. Percentages in the histograms indicate cells staining positive for the specific marker. (D) Mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) is shown for the indicated markers expressed on gated CD3-NK1.1+ Plcg2-/- splenocytes. Bars represent percentage values of MFI found on gated CD3-NK1.1+ WT splenocytes.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/107/3/10.1182_blood-2005-06-2428/4/m_zh80030690050001.jpeg?Expires=1767714562&Signature=x4x5c43JQDroy9fSMcy9ZBlyka2P0dcHkwQTSnR7URFogFXGx3dWrfE7SoA4j1XU3B6Bl0DBm6YW0jsovjJI~rKl3F6dRcMRUdkiLCuCnwiZPzc6g~G2GOiQb4Rbvb5uXl0OYTDbulj3Ba1MvLIos-s2WhWuh8GQ7anOcGKF6pNfToDxO4NWy0KXX9c6lhqd99l4fxSddBRHcKmgPw94EBqSD4JYzFfrbVo8ZiUsOP149EcaJAbjgidfDLrb43VJLDHM-YOlyX0psmyMKgxBu1gS~3l6QX5edZvG4cBaHhoDjM~SXFADwfmrkYSsoGqBTubk3fB~k6tIrXEPKUSzBg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal