Beutler and West have made a significant contribution in their comparison of hemoglobin levels in African-American patients with those of white patients from an outpatient clinic population by taking into account iron deficiency, the presence of α-thalassemia-1 and α-thalassemia-2 trait, and serum creatinine levels higher than 123.8 μM (1.4 mg/dL).1 Nevertheless even when individuals with these factors were eliminated from consideration, the African-Americans maintained a slightly lower mean hemoglobin level than did the white patients, and a higher percentage of African-Americans would have been considered anemic when using the criteria of a hemoglobin level of less than 135 g/L (13.5 g/dL) for men and less than 120 g/L (12 g/dL) for women.

The authors speculate on other possible genetic factors that could account for the difference in the average hemoglobin levels in the 2 populations. It is not clear from the article, however, whether the authors have taken into consideration the likely possibility of a higher frequency of hypertension and diabetes and therefore treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor and angiotensin receptor blockade medications in their African-American patients than would be found in the white patients.

I am a hematologist working in a hospital with a high percentage of African-American patients. In the last decade, we have been impressed by the increased number of patients referred to us for mild acquired anemia who have no other reason found after thorough evaluation except treatment with an ACE inhibitor and/or an angiotensin receptor antagonist. That inhibition of the renin-angiotensin system might result in anemia may be inferred from a number of observations.2 ACE inhibitors have been used successfully to ameliorate the erythrocytosis occurring at high altitude and that following renal transplantation.3,4 In vitro evidence also suggests that angiotensin II may act as a direct growth factor for erythroid progenitor cells.5 Angiotensin receptor antagonists reduced the number of erythroid burst-forming units in peripheral blood cultures from both chronic hemodialysis patients and healthy volunteers.5

It will be of great interest if Beutler and West can also examine the mean hemoglobin of the 2 groups after patients being treated with ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockade medications are also eliminated.

ACE inhibitors and anemia in African-Americans

Dr Schechter makes a very interesting and valid point: not all physiologic differences between ethnic groups need be of genetic origin. Environmental factors such as medications can be important. From the point of view of the clinician, her experience with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors is particularly interesting. The modest anemia that may result from the administration of one such drug, enalapril, has recently been documented1 in a large study. This is a cause of anemia that we should all bear in mind.

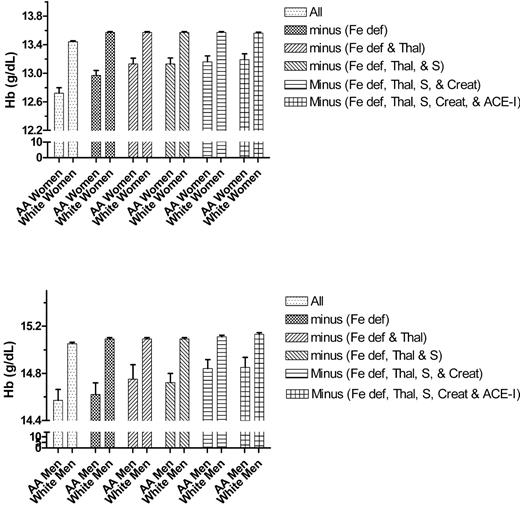

We are able to reanalyze the data for the effect of ACE inhibitors as suggested by Dr Schechter by removing from consideration all of the subjects who had filled a prescription for an ACE inhibitor. These drugs were liberally prescribed for our study population, almost entirely as lisinopril; approximately 26% of the black subjects and 16% of the white subjects had filled such prescriptions. We have expanded Figure 2 from our original publication to include a final column representing only those subjects who had not filled prescriptions for ACE inhibitors (Figure 1). There is essentially no difference when the patients receiving ACE inhibitors are excluded.

It is perhaps surprising that no effect was found, but it may be that some ACE inhibitors have more of a propensity to cause anemia than others. Moreover, most of the studies showing the development of anemia were performed in individuals with various complications of hypertension, such as renal disease. Thus, it may be that the effect of these drugs is less pronounced in an essentially well population; the single study that documented anemia in a more healthy population3 is difficult to interpret because the subjects were apparently subjected to phlebotomies totaling 1.3 liters in a month.

In another sense, the fact that the administration of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors does not account for the differences between white and black subjects is not surprising, since other studies have shown the difference to exist in children of all ages.4,5

The effect of sequentially removing subjects with iron deficiency, the α-thalassemia -3.7-kb allele, sickle trait, serum creatinine levels of more than 1.4 mg/dL, and those who had filled prescriptions for ACE inhibitors on the hemoglobin level (Hb) of African-American men and women and of age- and sex-matched white controls. An expansion of Figure 2 from Beutler and West.2 The effect on the hemoglobin level (Hb) of African-American men and women and of age- and sex-matched white controls of sequentially removing subjects with the following characteristics: iron deficiency, the α-thalassemia 3.7-kb allele, sickle trait, serum creatinine levels higher than 123.76 μM (1.4 mg/dL), and having filled a prescription for an ACE inhibitor. Top graph, women; bottom graph, men. Fe def indicates iron deficiency; Thal, α-thalassemia 3.7-kb allele; S, sickle trait; Creat, serum creatinine levels higher than 1.4 mg/dL; and ACE-I, a history of having filled a prescription for an ACE inhibitor. Error bars indicate SEM.

The effect of sequentially removing subjects with iron deficiency, the α-thalassemia -3.7-kb allele, sickle trait, serum creatinine levels of more than 1.4 mg/dL, and those who had filled prescriptions for ACE inhibitors on the hemoglobin level (Hb) of African-American men and women and of age- and sex-matched white controls. An expansion of Figure 2 from Beutler and West.2 The effect on the hemoglobin level (Hb) of African-American men and women and of age- and sex-matched white controls of sequentially removing subjects with the following characteristics: iron deficiency, the α-thalassemia 3.7-kb allele, sickle trait, serum creatinine levels higher than 123.76 μM (1.4 mg/dL), and having filled a prescription for an ACE inhibitor. Top graph, women; bottom graph, men. Fe def indicates iron deficiency; Thal, α-thalassemia 3.7-kb allele; S, sickle trait; Creat, serum creatinine levels higher than 1.4 mg/dL; and ACE-I, a history of having filled a prescription for an ACE inhibitor. Error bars indicate SEM.

Correspondence: Ernest Beutler, Dept Molecular and Experimental Medicine (MEM-215), The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 N Torrey Pines Rd, La Jolla, CA 92037; e-mail: beutler@scripps.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal