Previous analyses of the roles of α4 integrins in hematopoiesis by other groups have led to conflicting evidence. α4 integrin mutant cells developing in [α4 integrin–/–: wt] chimeric mice are not capable of completing lymphomyeloid differentiation, whereas conditional inactivation of α4 integrin in adult mice has only subtle effects. We show here that circumventing the fetal stage of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) development by transplantation of embryonic α4 integrin–/– cells into the adult microenvironment results in robust and stable long-term generation of α4 integrin–/– lymphoid and myeloid cells, although colonization of Peyer patches and the peritoneal cavity is significantly impaired. We argue here that collectively, our data and the data from other groups suggest a specific requirement for α4 integrin during the fetal/neonatal stages of HSC development that is essential for normal execution of the lymphomyeloid differentiation program.

Introduction

The first emergence of highly repopulating definitive hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) occurs at E10.5-E11.5 in the aorta-gonadmesonephros (AGM) region and placenta and, with a slight delay, in the yolk sac (YS).1-7 The emergence of HSCs is closely followed by their expansion and transit via the circulation into the fetal liver (FL) from E11.5 and subsequently to the bone marrow (BM) shortly after birth.4,6,8 Adhesion molecules, including integrins, play important roles in the development, homing, and functioning of HSCs and progenitor cells.9

The study of β1 integrin knockout mice established a strict dependence of HSC homing to the FL and adult hematopoietic organs on this molecule,10,11 which corroborated earlier observations that infusion with anti–β1 integrin blocking antibodies inhibited the formation of myeloid spleen colonies and medullary hematopoiesis in vivo.12 Among the many β1 integrin heterodimeric complexes involving α integrin subunits, α4β1 integrin (VLA-4) is one of the important players in hematopoiesis.9,13 Associations between VLA-4 and VCAM-114,15 and VLA-4 and fibronectin (via the Cs-1 sequence)16-19 mediate the interactions of progenitor cells with hematopoietic stroma. Addition of blocking anti–α4 integrin antibodies to long-term BM cultures completely inhibits lymphopoiesis and retards myelopoiesis in long-term BM cultures.20 Anti–α4 integrin (but not anti–α5 integrin) and anti–VCAM-1 antibodies suppress formation of blast colony-forming cells on stroma in vitro.21 The in vivo injection of cells incubated with anti–α4 integrin or infusion of anti–VCAM-1 antibodies results in a decreased homing efficiency of progenitor spleen colony-forming unit and colony-forming unit culture cells to the BM.22 In addition, administration of blocking antibodies to α4 integrin and VCAM-1 causes stem/progenitor cell mobilization in vivo and potentiates the mobilization effects of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and stem cell factor.23-27 Binding of α4 integrin to fibronectin also has been shown to be important for recruiting erythroid progenitors in the BM.12,28 Another heterodimeric complex involving α4 integrin, α4β7, and its ligand MAdCAM-1 have been shown to be important for the homing of hematopoietic progenitors to the BM,29 as well as the homing of lymphocytes to Peyer patches.30-33

Generation of α4 integrin knockout mice by Arroyo et al34,35 enabled further analysis of the role of α4 integrin in hematopoiesis. α4 integrin–/– embryos have smaller and paler livers and usually die by E12.5 due to heart and, perhaps, placental defects.36 Consequently, the role of α4 integrins in the later stages of development has been studied in [α4 integrin–/–: wt] and [α4 integrin–/–: Rag–/–] chimeric animals generated by injection of α4 integrin–/– embryonic stem cells into wild-type or Rag–/– blastocysts.34,35 α4 integrin–/– erythroid, myeloid, and B-lymphoid progenitors are present in the FL of chimeric embryos, but progressively lose their capacity to complete differentiation. In adult mice, α4 integrin–/– progenitors migrate to the spleen and BM but are unable to substantially contribute to the erythroid, myeloid, and B-lymphoid lineages.34,35 This differentiation block can be released in vitro, and it has been proposed that interaction with stroma via α4 integrin in vivo is essential for hematopoietic differentiation. The T-lymphoid lineage also shows signs of compromised development in the embryonic thymus.34,35 After birth, the development of α4 integrin–/– T lymphocytes in the adult thymus is blocked prior to the CD4/CD8α double-positive stage, with thymi becoming progressively atrophic in [α4 integrin–/–: Rag–/–] chimeras. These data confirm a fundamental role for α4 integrin in hematopoietic development and differentiation, as suggested previously by antibody-blocking experiments.

In contrast, conditional deletion of α4 integrin in adult mice by Scott et al37 resulted in only minor perturbations in hematopoiesis, such as an efflux of hematopoietic progenitors from the BM, with a consequential increase in progenitors in the spleen and blood. Lymphoid (CD4+ T cells and B220+ B cells), but not myeloid, populations of the BM also were slightly compromised.37 These minor effects are in marked contrast with the dramatic inability of α4 integrin–/– hematopoietic cells to be maintained and differentiated in the [α4 integrin–/–: wt] chimeric environment. This discrepancy can be explained either by (1) a competitive disadvantage of α4 integrin–/– cells in the presence of wild-type counterparts in chimeric animals, or (2) an essential role that α4 integrins play during embryonic and/or fetal/neonatal development of HSCs (but not in the adult), implying that in their absence, the development/differentiation program of HSCs becomes corrupt.

To discriminate between these possibilities, we investigated the developmental potential of early (embryonic) definitive α4 integrin–/– HSCs. We have found that HSCs express α4 integrin throughout development, and in its absence the initial pattern of HSC allocation in the embryo is only slightly perturbed. Early embryonic α4 integrin–/– HSCs that have bypassed fetal/neonatal development via transplantation directly into the adult differentiate normally and contribute stably and robustly to adult hematopoiesis (although the level of donor contribution tends to be lower than for mice receiving wild-type transplants). Furthermore, the differentiation of donor-derived α4 integrin–/– hematopoietic cells is not compromised by the presence of cotransplanted wild-type BM cells, and major cell subsets home normally to adult tissues, with the exception of the Peyer patches and the peritoneal cavity. We conclude that α4 integrin is critically important for HSCs to be able to develop through the fetal/neonatal stage and maintain their normal differentiation potential.

Materials and methods

Animals and tissues

CBA, C57BL/6, and (CBA × C57BL/6) F1 mice were bred in the animal breeding unit of the University of Edinburgh in compliance with Home Office regulations. Cell suspensions were prepared from E11.5-E13.5 embryonic tissues by treating them with 0.1% collagenase-dispase (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 37°C. Peripheral circulation was collected in PBS and put on ice within 2 to 3 minutes of collection. Wild-type and α4 integrin–/– embryo donor tissues isolated from (CBA × C57BL/6) F1 embryos were transplanted into congenic (CBA × C57BL/6) F1 Ly-5.1/1 or Ly-5.1/2 recipients. In some experiments, (CBA × C57BL/6) F1 wild-type GFP+ and α4 integrin–/–GFP+ donor tissues were used for transplantation into (CBA × C57BL/6) F1 wild-type recipients.38 In all cases, α4 integrin–/– embryos were genotyped by flow cytometry and polymerase chain reaction analysis. Additionally, upon the analysis of recipient peripheral blood (PB) after transplantation, donor cells were confirmed via flow cytometry to be lacking α4 integrin expression (Figure 4A). Irradiation of recipients and transplantations, including co-injection of 20 000 BM cells (containing on average 2 HSCs) per mouse, was performed as described previously.4 At time points of 6, 12 to 19, and more than 19 weeks after transplantation, the donor cell contribution was assessed by flow cytometry using Ly-5.1 and Ly-5.2 antibodies, or in some cases by green fluorescent protein expression. Recipients were considered reconstituted if the donor chimerism in the peripheral blood was at least 5%.

Organ explant culture

E11.5 AGM regions isolated from (CBA × C57BL/6) F1 embryos were cultured on Durapore 0.65 μm filters (Millipore, Watford, United Kingdom) as described previously.4

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed using a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) and evaluated with FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). Cell suspensions from embryonic tissues were obtained following 0.1% collagenase-dispase treatment, from adult BM mechanically using a syringe, and from other adult tissues by grinding in PBS. For peritoneal lavage, room-temperature PBS was used, and cells were put on ice directly following collection. Except where indicated, adult peripheral blood, BM, and spleen red blood cells were lysed using PharMLyse (BD Biosciences, Oxford, United Kingdom). Staining was performed with directly conjugated antibodies (Ly-5.1 FITC [A20], Ly-5.2 FITC [104], CD41 FITC [MWReg30], CD11b FITC [M1/70], Sca-1 FITC [E13-161.7], IgM FITC [R6-60.2], CD45 FITC [30-F11], CD34 FITC [RAM34], Ly-5.1 PE [A20], Ly-5.2 PE [104], CD3ϵ PE [145-2C11], CD49d PE [9C10], CD11b PE [M1/70], Ter119 PE [TER-119], CD8α PE [53-6.7], CD19 PE [1D3], CD44 PE [IM7], Sca-1 PE [D7], IgD [11-26], Ly-5.1 APC [A20], c-Kit APC [2B8], AA4.1 APC [AA4.1], Gr1 biotin [RB6-8C5], B220 biotin [RA3-6B2], CD49d biotin [9C10], CD41 biotin [MWReg30], Ter119 biotin [TER-119], CD3ϵ biotin [145-2C11], and CD11b Biotin [M1/70]). Streptavidin APC and streptavidin PE-Cy5.5 were used for detection of primary biotinylated antibodies. Dead-cell exclusion was performed using 7-AAD in all instances. All reagents were purchased from BD Biosciences (Oxford, United Kingdom) and eBiosciences (San Diego, CA). All gates were set based on appropriate isotype control stainings.

Statistical analysis

Fisher exact test with contingency tables was used to compute statistical significance of repopulation assay results. All other statistics were performed using unpaired Student 2-tailed t test.

Results

Phenotypic characterization of α4 integrin in the developing hematopoietic system

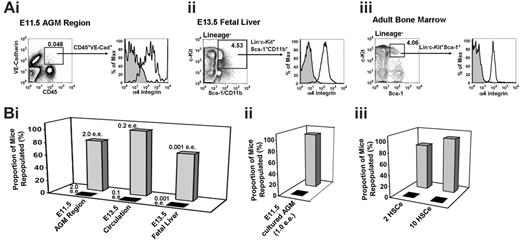

We have flow-cytometrically characterized the expression of α4 integrin in hematopoietic cell subsets during development in the E11.5 AGM region, E13.5 FL, and adult BM. To this end, cells from these tissues were stained with antibodies against CD45 (pan-leukocyte), CD41 (early progenitors; megakaryocytes), CD11b (monocytes; embryonic/fetal HSCs), Ter119 (erythroid cells), c-Kit, and CD34 and analyzed by flow cytometry (Figure 1). In the E11.5 AGM region, most, if not all, CD45+, CD41+, and CD11b+ cells express α4 integrin. In contrast, erythroid cells (Ter119+ subset) lack α4 integrin expression.

Approximately 30% of c-Kit+ cells in the E11.5 AGM region coexpress α4 integrin (Figure 1). According to the previous studies, the remaining 70% of c-Kit+ cells include erythroid39 and nonhematopoietic cells.40 In contrast, expression of CD34 and α4 integrin is largely mutually exclusive, which is likely related to the fact that many CD34+ cells are endothelial41 (most VE-cadherin+ endothelial cells are α4 integrin–42 ). However, a rare population of CD34+α4 integrin+ cells can be detected in the E11.5 AGM region (Figure 1). Of note, HSCs in the AGM region are c-Kit+CD34+.43

α4 integrin expression in embryonic tissues and adult BM. Flow cytometrical analysis of α4 integrin coexpression with hematopoietic markers at key developmental stages. Dead cells were excluded using 7-AAD. Red blood cells were gated out for all adult bone marrow samples using forward scatter/side scatter plots, except where indicated (‡; all BM samples were unlyzed). Quadrants were placed according to appropriate isotype controls. (Collagenase-dispase treatment of BM produces similar staining patterns/intensities [data not shown].)

α4 integrin expression in embryonic tissues and adult BM. Flow cytometrical analysis of α4 integrin coexpression with hematopoietic markers at key developmental stages. Dead cells were excluded using 7-AAD. Red blood cells were gated out for all adult bone marrow samples using forward scatter/side scatter plots, except where indicated (‡; all BM samples were unlyzed). Quadrants were placed according to appropriate isotype controls. (Collagenase-dispase treatment of BM produces similar staining patterns/intensities [data not shown].)

At a later point in development, in the E13.5 FL, nonerythroid hematopoietic CD45+ cells remain largely α4 integrin+; however, a significant portion of the erythroid population also becomes α4 integrin+ (Figure 1). All c-Kit+, CD11b+, and CD41+ cells also express α4 integrin. In the adult BM, the leukocytic (CD45+, CD41+, CD11b+) compartments are almost entirely α4 integrin+, whereas about half of the erythroid (Ter119+) population is α4 integrin–. As in the E13.5 FL, the majority of c-Kit+ cells express α4 integrin. Most, if not all, CD34+ cells in the BM become α4 integrin+.

Embryonic and adult definitive HSCs express α4 integrin

We have made further investigations into the expression of α4 integrin on HSC-enriched populations during embryonic development and in the adult. The first highly repopulating definitive HSCs emerging in the E11.5 AGM region reside within the CD45+VE-cadherin+ population.42,44 Most cells in this double-positive population are α4 integrin+ (Figure 2Ai, and Taoudi et al42 ). To functionally test whether HSCs in the AGM express α4 integrin, α4 integrin+ and α4 integrin– cells sorted from the E11.5 AGM region were injected into irradiated recipients. As shown in Figure 2Bi, only the mice that received transplants of α4 integrin+ cells were reconstituted.

Phenotypic and functional evidence that embryonic and adult HSCs express α4 integrin. (A) Adult and embryonic tissues have been analyzed for α4 integrin expression in their respective HSC-enriched populations. (Isotype control = filled curve; α4 integrin = empty curve.) (Ai) The CD45+VE-cadherin+ population, enriched with HSCs in the E11.5 AGM region,42,44 is α4 integrin+. (Aii) The lineage– c-Kit+Sca-1+CD11b+ population, enriched with HSCs in the fetal liver,45 is α4 integrin+. (Aiii) The lineage– c-Kit+Sca-1+ fraction, enriched with HSCs in the adult BM,29 is α4 integrin+. (B) α4 integrin+ (▦) and α4 integrin– (▴) fractions were isolated by flow sorting based on staining with anti–α4 integrin antibody and transplanted into irradiated recipient mice. Dead cells were excluded using 7-AAD. The percentage of mice repopulated out of the total number receiving transplants is indicated (for actual numbers of mice, see Table S1). ee indicates embryo equivalent; HSCe, bone marrow hematopoietic stem cell equivalent. (Bi) Uncultured embryonic tissues. (Bii) Cultured E11.5 AGM region. (Biii) Adult BM (unlysed erythrocytes were gated out).

Phenotypic and functional evidence that embryonic and adult HSCs express α4 integrin. (A) Adult and embryonic tissues have been analyzed for α4 integrin expression in their respective HSC-enriched populations. (Isotype control = filled curve; α4 integrin = empty curve.) (Ai) The CD45+VE-cadherin+ population, enriched with HSCs in the E11.5 AGM region,42,44 is α4 integrin+. (Aii) The lineage– c-Kit+Sca-1+CD11b+ population, enriched with HSCs in the fetal liver,45 is α4 integrin+. (Aiii) The lineage– c-Kit+Sca-1+ fraction, enriched with HSCs in the adult BM,29 is α4 integrin+. (B) α4 integrin+ (▦) and α4 integrin– (▴) fractions were isolated by flow sorting based on staining with anti–α4 integrin antibody and transplanted into irradiated recipient mice. Dead cells were excluded using 7-AAD. The percentage of mice repopulated out of the total number receiving transplants is indicated (for actual numbers of mice, see Table S1). ee indicates embryo equivalent; HSCe, bone marrow hematopoietic stem cell equivalent. (Bi) Uncultured embryonic tissues. (Bii) Cultured E11.5 AGM region. (Biii) Adult BM (unlysed erythrocytes were gated out).

We then analyzed α4 integrin expression in enriched populations of definitive HSCs in E13.5 FL45 and adult BM.46 We found that the HSC-enriched lineage– c-Kit+Sca-1+CD11b+ cell fraction of the E13.5 FL expresses α4 integrin (Figure 2Aii). Similarly, the lineage– c-Kit+Sca-1+ fraction of adult BM, which contains HSCs, is entirely α4 integrin+ (Figure 2Aiii, and Katayama et al29 ). To functionally confirm the expression of α4 integrin on HSCs, in a separate experiment we sorted the α4 integrin+ and the α4 integrin– populations from these tissues and E13.5 circulation and transplanted them into irradiated recipients. Only the α4 integrin+ fractions demonstrated long-term repopulation capacity (Figure 2Bi,iii). The data in Figure 2 demonstrate the association of α4 integrin expression with HSCs throughout development.

We also tested whether HSCs that have undergone expansion in ex vivo AGM organ culture maintain α4 integrin expression.2,4 In line with ubiquitous expression of α4 integrin on HSCs throughout development and in adult life, HSCs expanded in vitro also were found to reside exclusively within the α4 integrin+ cell fraction (Figure 2Bii).

Early generation of definitive HSCs in the embryo is only slightly perturbed in the absence of α4 integrin

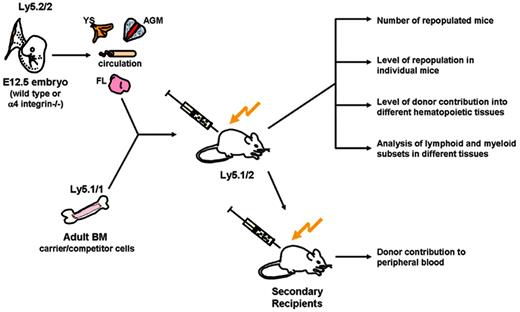

Given that HSCs throughout development express α4 integrin, using α4 integrin knockout mice, we were able to investigate the specific role of α4 integrin in embryonic HSC emergence and distribution. Although α4 integrin–/– hematopoietic cells are able to develop and reside within the adult BM (as shown by Arroyo et al34,35 in [α4 integrin–/–: wt] chimeric mice), their differentiation capacity is severely compromised. Initially, we considered the possibility that this could be the result of a severe HSC deficiency in the early embryo. Therefore, we assessed the distribution and differentiation capacity of HSCs in 4 sites that play important roles in HSC development.4,6 Cell suspensions were prepared from E12.5 AGM region, PB, YS, and livers of wild-type and α4 integrin–/– embryos and transplanted as fractions of embryo equivalents (ee) into irradiated recipients. Analysis was carried out on recipients to assess the proportion of mice reconstituted with α4 integrin–/– cells. Comparisons also were made between the levels of donor contribution in the peripheral blood of α4 integrin–/– and wild-type recipients of transplants. Additionally, we assessed the homing and differentiation capacity of α4 integrin–/– HSCs in principle hematopoietic tissues (see Figure 3 for experimental design).

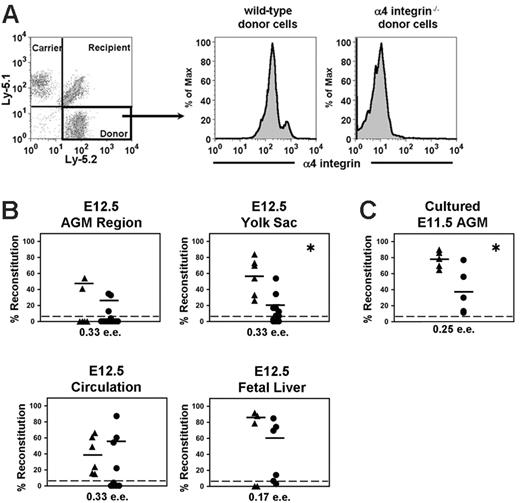

The proportion of mice reconstituted with α4 integrin–/– cells was in general slightly lower but statistically comparable to recipients that received transplants of wild-type embryonic tissues (Figure 4B and Table S2, which is available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Tables link at the top of the online article). The level of donor cell contribution for mice that received transplants of α4 integrin–/– embryonic tissues also tended to be lower (except with the circulation) as compared to the wild-type recipients of transplants (Figure 4B). However, this trend is statistically significant only with YS-derived HSCs.

We then tested whether HSC expansion can occur in the AGM organ culture assay in the absence of α4 integrin.2,4 To this end, E11.5 AGM regions from α4 integrin–/– and wild-type embryos were cultured for 4 days and transplanted into irradiated recipients (0.25 ee/recipient) (Figure 4C). All 5 animals in each experimental group were reconstituted (Figure 4C). Since it is likely that only one mouse would be reconstituted with 0.25 ee of fresh AGM prior to culture, this result indicates that HSCs are able to expand in the absence of α4 integrin. However, the average level of contribution per recipient was statistically lower in the absence of α4 integrin.

The significance of the observation that the level of reconstitution tends to be slightly lower with α4 integrin–/– cells is unclear since α4 integrin–/– embryos die by E12.5 due to heart and placenta defects.36 This may have nonspecific impact(s) on hematopoietic development. In any case, the slight underperformance of transplanted α4 integrin–/– HSCs is not comparable to the marked failure of α4 integrin–/– cells continuing their development in the [α4 integrin–/–: wt] embryo.34,35

Experimental design. Cell suspensions prepared from embryonic (wild-type or α4 integrin–/–) tissues were cotransplanted with competitor wild-type BM cells intravenously into adult irradiated recipients. Primary recipients were analyzed using various approaches. Repopulation activity was assessed by 2 different (but complementary) criteria: (1) the number of recipient mice repopulated, and (2) the level of repopulation of individual mice (≥ 5%). Colonization capacity was assessed by donor repopulation of different recipient tissues. Differentiation capacity was assessed by the analysis of lymphoid and myeloid cell subsets in recipient hematopoietic tissues. Serial transplantations of α4 integrin–/– BM cells also were carried out and the peripheral blood of secondary recipients analyzed for donor contribution.

Experimental design. Cell suspensions prepared from embryonic (wild-type or α4 integrin–/–) tissues were cotransplanted with competitor wild-type BM cells intravenously into adult irradiated recipients. Primary recipients were analyzed using various approaches. Repopulation activity was assessed by 2 different (but complementary) criteria: (1) the number of recipient mice repopulated, and (2) the level of repopulation of individual mice (≥ 5%). Colonization capacity was assessed by donor repopulation of different recipient tissues. Differentiation capacity was assessed by the analysis of lymphoid and myeloid cell subsets in recipient hematopoietic tissues. Serial transplantations of α4 integrin–/– BM cells also were carried out and the peripheral blood of secondary recipients analyzed for donor contribution.

Long-term repopulation assay with α4 integrin–/– and wild-type embryonic tissues. (A) A representative plot demonstrates repopulation with embryonic E12.5 yolk sac (α4 integrin–/–) plus 20 000 competitor carrier (wild-type) bone marrow cells using the Ly-5.1/Ly-5.2 system. α4 integrin–/– repopulating yolk sac–derived cells show an absence of α4 integrin expression (right plot). The intermediate plot demonstrates that recipients of wild-type embryonic transplants express α4 integrin. (B) Transplantations with E12.5 tissues are plotted as the percentage of donor contribution in the peripheral blood of each mouse. (C) Transplantations with 4-day cultured α4 integrin–/– (•) and wild-type (▴) E11.5 AGM region. Plotted horizontal lines represent the mean percentage level of reconstitution in the peripheral blood for each set of recipient mice. (*P < .05, comparison between wild-type and α4 integrin–/– reconstitution levels.) Note that by using another method for assessment of reconstitution, which compares the number of reconstituted mice out of the total that received transplants of wild-type and α4 integrin–/– cells, there is no significant difference between these 2 groups for all tissues transplanted. (For statistics, see Table S2.)

Long-term repopulation assay with α4 integrin–/– and wild-type embryonic tissues. (A) A representative plot demonstrates repopulation with embryonic E12.5 yolk sac (α4 integrin–/–) plus 20 000 competitor carrier (wild-type) bone marrow cells using the Ly-5.1/Ly-5.2 system. α4 integrin–/– repopulating yolk sac–derived cells show an absence of α4 integrin expression (right plot). The intermediate plot demonstrates that recipients of wild-type embryonic transplants express α4 integrin. (B) Transplantations with E12.5 tissues are plotted as the percentage of donor contribution in the peripheral blood of each mouse. (C) Transplantations with 4-day cultured α4 integrin–/– (•) and wild-type (▴) E11.5 AGM region. Plotted horizontal lines represent the mean percentage level of reconstitution in the peripheral blood for each set of recipient mice. (*P < .05, comparison between wild-type and α4 integrin–/– reconstitution levels.) Note that by using another method for assessment of reconstitution, which compares the number of reconstituted mice out of the total that received transplants of wild-type and α4 integrin–/– cells, there is no significant difference between these 2 groups for all tissues transplanted. (For statistics, see Table S2.)

Embryonic α4 integrin–/– definitive HSCs show stable long-term levels of engraftment and differentiate normally in adult recipients

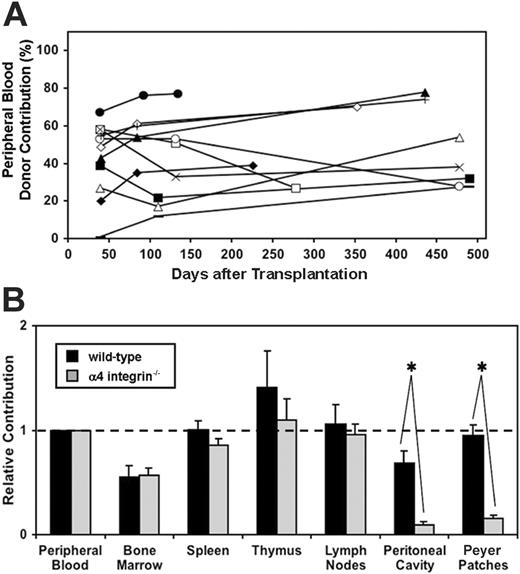

Having established a possible defect in α4 integrin–/– HSCs, as evidenced by the trend for lower mean chimerism levels in the peripheral blood as compared to wild-type mice receiving transplants, we examined the reconstitution stability and long-term differentiation capacity of α4 integrin–/– HSCs in the presence of wild-type competitor cells. Importantly, we found that α4 integrin–/– donor-derived cells are not outcompeted by cotransplanted wild-type BM competitor cells. Both embryonic tissues (YS, AGM, and PB) and the cotransplanted 20 000 BM cells contain approximately 1 to 2 HSCs.4 As illustrated in Table 1, α4 integrin–/– embryonic cells and competitor BM cells coexist long-term in the peripheral blood. Furthermore, contribution of α4 integrin–/– cells to the peripheral blood was found to be stable up to 500 days after transplantation (Figure 5A).

Coexistence of donor embryonic cells with competitor BM cells

. | Wild-type donor . | . | . | . | α4 integrin-/- donor . | . | . | . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | Mouse 1, AGM . | Mouse 2, YS . | Mouse 3, PB . | Mouse 4, FL . | Mouse 1, AGM . | Mouse 2, YS . | Mouse 3, PB . | Mouse 4, FL . | ||||||

| Embryonic donor, % | 54 | 33 | 16 | 42 | 34 | 35 | 60 | 47 | ||||||

| Competitive bone marrow, % | 14 | 9 | 35 | 9 | 44 | 13 | 10 | 27 | ||||||

. | Wild-type donor . | . | . | . | α4 integrin-/- donor . | . | . | . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | Mouse 1, AGM . | Mouse 2, YS . | Mouse 3, PB . | Mouse 4, FL . | Mouse 1, AGM . | Mouse 2, YS . | Mouse 3, PB . | Mouse 4, FL . | ||||||

| Embryonic donor, % | 54 | 33 | 16 | 42 | 34 | 35 | 60 | 47 | ||||||

| Competitive bone marrow, % | 14 | 9 | 35 | 9 | 44 | 13 | 10 | 27 | ||||||

In conjunction with Figures 5A and 6, this table illustrates clearly that there is no defect in homing or multilineage differentiation of α4 integrin-/- embryonic HSCs in the presence of substantial numbers of competitor BM cells (as compared to similar embryonic wild-type HSCs contransplanted with competitor BM cells).

The embryonic donor organ is given for each recipient mouse. Analysis of peripheral blood for donor and competitive BM percentages was performed 12 weeks after transplantation.

AGM indicates aorta-gonads-mesonephros region; YS, yolk sac; PB, peripheral blood; and FL, fetal liver.

Contribution of α4 integrin–/– and wild-type embryonic cells to lymphohematopoietic tissues. (A) The level of reconstitution in the peripheral blood of recipient mice is maintained over time, up to 500 days after transplantation. Each symbol and connecting line represents an individual mouse that has been reconstituted with α4 integrin–/– E12.5 fetal liver (n = 5), yolk sac (n = 2), AGM region (n = 1), or peripheral blood (n = 4). (B) Mice that received transplants of α4 integrin–/– ( ) or wild-type (▪) E12.5 embryonic tissues (fetal liver, AGM region, yolk sac, and peripheral blood) were analyzed for donor contribution in various tissues using flow cytometry. Note the deficiency in colonization of the peritoneal cavity and the Peyer patches with α4 integrin–/– cells. The mean for relative contribution, as compared to the percent reconstitution in peripheral blood, is plotted. Bars represent standard error (*P < .01; wild-type n = 7, α4 integrin–/– n = 7).

) or wild-type (▪) E12.5 embryonic tissues (fetal liver, AGM region, yolk sac, and peripheral blood) were analyzed for donor contribution in various tissues using flow cytometry. Note the deficiency in colonization of the peritoneal cavity and the Peyer patches with α4 integrin–/– cells. The mean for relative contribution, as compared to the percent reconstitution in peripheral blood, is plotted. Bars represent standard error (*P < .01; wild-type n = 7, α4 integrin–/– n = 7).

Contribution of α4 integrin–/– and wild-type embryonic cells to lymphohematopoietic tissues. (A) The level of reconstitution in the peripheral blood of recipient mice is maintained over time, up to 500 days after transplantation. Each symbol and connecting line represents an individual mouse that has been reconstituted with α4 integrin–/– E12.5 fetal liver (n = 5), yolk sac (n = 2), AGM region (n = 1), or peripheral blood (n = 4). (B) Mice that received transplants of α4 integrin–/– ( ) or wild-type (▪) E12.5 embryonic tissues (fetal liver, AGM region, yolk sac, and peripheral blood) were analyzed for donor contribution in various tissues using flow cytometry. Note the deficiency in colonization of the peritoneal cavity and the Peyer patches with α4 integrin–/– cells. The mean for relative contribution, as compared to the percent reconstitution in peripheral blood, is plotted. Bars represent standard error (*P < .01; wild-type n = 7, α4 integrin–/– n = 7).

) or wild-type (▪) E12.5 embryonic tissues (fetal liver, AGM region, yolk sac, and peripheral blood) were analyzed for donor contribution in various tissues using flow cytometry. Note the deficiency in colonization of the peritoneal cavity and the Peyer patches with α4 integrin–/– cells. The mean for relative contribution, as compared to the percent reconstitution in peripheral blood, is plotted. Bars represent standard error (*P < .01; wild-type n = 7, α4 integrin–/– n = 7).

To investigate the homing efficiency of α4 integrin–/– HSCs/progenitors to principle hematopoietic organs, we assessed the donor contribution of α4 integrin–/– cells in individual tissues. To account for variation in PB chimerism, results are reported quantitatively in relation to the contribution in the peripheral blood. In the BM, spleen, thymus, and lymph nodes we obtained statistically similar results to those acquired with wild-type HSCs (Figure 5B).

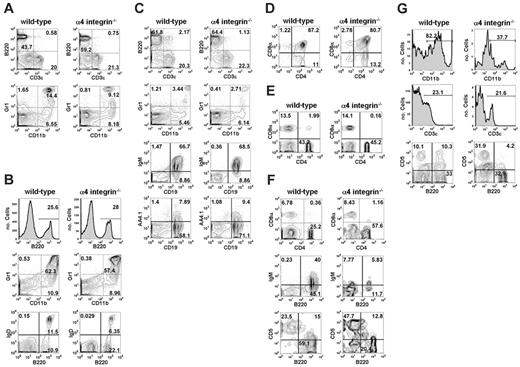

We also analyzed the multilineage differentiation of α4 integrin–/– cells and found populations of myeloid and lymphoid cells in peripheral blood, BM, and spleen to be comparable to wild-type embryonic cells (Figure 6A-C, Table 2). In these tissues, no obvious difference was observed in the percentage of CD11b+Gr1+ and CD11b+Gr1– myeloid populations within the α4 integrin–/– donor population as compared to mice reconstituted with wild-type cells. Similarly, donor B cells (B220+) and T cells (CD3ϵ+) in these tissues were comparable in mice reconstituted with α4 integrin–/– or wild-type embryonic HSCs. Further analysis showed that α4 integrin–/– HSCs differentiate normally into mature B220+IgD+ B cells in the recipient bone marrow (representative plots and statistics shown in Figure 6B and Table 2). CD19/AA4.1 co-staining in the spleen (8.8% ± 1.0% for wild-type and 10.3% ± 0.7% for α4 integrin–/–) demonstrates a normal capacity for α4 integrin–/– immature B cells to populate the spleen (Figure 6C and Table 2). Furthermore, maturation of B cells in the spleen does not depend on α4 integrin: we show that wild-type donor-derived CD19+IgM+ cells constitute 57% ± 5% in the spleen, and likewise α4 integrin–/– donor cells give rise to a comparable population of these cells (55.8% ± 5.3%) (Figure 6C).

Statistical analysis of α4 integrin–/– and wild-type donor cell subsets in recipient tissues

. | Wild type, mean ± SEM (no.) . | α4 integrin-/-, mean ± SEM (no.) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peripheral blood | |||

| CD3ϵ+ | 21.8 ± 3.5 (6) | 21.0 ± 6.9 (8) | .92 |

| B220+ | 54.8 ± 3.1 (6) | 59.4 ± 5.7 (8) | .50 |

| CD11b+Gr1- | 5.7 ± 1.3 (6) | 7.4 ± 1.9 (7) | .46 |

| CD11b+Gr1+ | 13.1 ± 3.0 (6) | 10.3 ± 2.7 (7) | .50 |

| Bone marrow | |||

| B220+ | 29.0 ± 6.0 (9) | 24.3 ± 2.4 (10) | .48 |

| CD11b+Gr1- | 10.9 ± 1.2 (9) | 9.4 ± 1.1 (8) | .37 |

| CD11b+Gr1+ | 51.6 ± 5.9 (9) | 49.6 ± 6.4 (8) | .74 |

| B220+IgD+ | 9.8 ± 0.5 (5) | 17.0 ± 3.2 (3) | .15 |

| B220+IgD- | 12.2 ± 4.5 (5) | 5.5 ± 1.6 (3) | .22 |

| Spleen | |||

| CD3ϵ+ | 20.6 ± 2.9 (5) | 24.2 ± 3.5 (6) | .46 |

| B220+ | 64.0 ± 2.0 (5) | 63.0 ± 3.9 (6) | .83 |

| CD11b+Gr1- | 5.2 ± 1.4 (5) | 4.1 ± 0.6 (5) | .51 |

| CD11b+Gr1+ | 3.2 ± 0.8 (5) | 1.5 ± 0.5 (5) | .12 |

| CD19+IgM+ | 57.0 ± 5.0 (3) | 55.8 ± 5.3 (4) | .87 |

| CD19+IgM- | 15.3 ± 3.2 (3) | 14.0 ± 2.9 (4) | .77 |

| CD19+AA4.1+ | 8.8 ± 1.0 (6) | 10.3 ± 0.7 (3) | .26 |

| CD19+AA4.1- | 64.8 ± 2.8 (6) | 66.0 ± 2.9 (3) | .78 |

| Thymus | |||

| CD4 SP | 10.7 ± 1.9 (6) | 13.8 ± 1.9 (5) | .28 |

| CD8α SP | 2.8 ± 0.9 (6) | 4.0 ± 0.6 (5) | .32 |

| CD4+CD8α+ | 77.0 ± 7.2 (6) | 67.2 ± 6.8 (5) | .35 |

| Lymph nodes | |||

| CD4 SP | 47.3 ± 3.3 (6) | 40.2 ± 5.4 (5) | .30 |

| CD8α SP | 21.0 ± 1.7 (6) | 18.4 ± 1.9 (5) | .34 |

| Peyer patches | |||

| CD4 SP | 23.9 ± 4.9 (7) | 45.4 ± 7.4 (8) | .03 |

| CD8α SP | 7.7 ± 1.6 (7) | 7.8 ± 1.4 (8) | .90 |

| B220+ | 69.7 ± 5.5 (7) | 25.5 ± 5.3 (8) | <.001 |

| B220+IgM+ | 40.0 (1) | 6.4 ± 1.5 (5) | NA |

| B220+IgD+ | 52.7 ± 10.0 (3) | ND | NA |

| B220+CD5+ | 15.0 ± 0.7 (4) | 13.1 ± 1.8 (5) | .40 |

| Peritoneal cavity | |||

| CD11b+ | 80.8 ± 4.4 (5) | 44.1 ± 8.4 (8) | <.01 |

| CD3ϵ+ | 19.2 ± 5.8 (5) | 21.1 ± 4.1 (7) | .80 |

| B220+ | 47.3 ± 2.7 (8) | 33.7 ± 9.0 (7) | .20 |

| B220+CD5+ | 12.5 ± 1.4 (4) | 3.9 ± 1.7 (5) | <.01 |

. | Wild type, mean ± SEM (no.) . | α4 integrin-/-, mean ± SEM (no.) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peripheral blood | |||

| CD3ϵ+ | 21.8 ± 3.5 (6) | 21.0 ± 6.9 (8) | .92 |

| B220+ | 54.8 ± 3.1 (6) | 59.4 ± 5.7 (8) | .50 |

| CD11b+Gr1- | 5.7 ± 1.3 (6) | 7.4 ± 1.9 (7) | .46 |

| CD11b+Gr1+ | 13.1 ± 3.0 (6) | 10.3 ± 2.7 (7) | .50 |

| Bone marrow | |||

| B220+ | 29.0 ± 6.0 (9) | 24.3 ± 2.4 (10) | .48 |

| CD11b+Gr1- | 10.9 ± 1.2 (9) | 9.4 ± 1.1 (8) | .37 |

| CD11b+Gr1+ | 51.6 ± 5.9 (9) | 49.6 ± 6.4 (8) | .74 |

| B220+IgD+ | 9.8 ± 0.5 (5) | 17.0 ± 3.2 (3) | .15 |

| B220+IgD- | 12.2 ± 4.5 (5) | 5.5 ± 1.6 (3) | .22 |

| Spleen | |||

| CD3ϵ+ | 20.6 ± 2.9 (5) | 24.2 ± 3.5 (6) | .46 |

| B220+ | 64.0 ± 2.0 (5) | 63.0 ± 3.9 (6) | .83 |

| CD11b+Gr1- | 5.2 ± 1.4 (5) | 4.1 ± 0.6 (5) | .51 |

| CD11b+Gr1+ | 3.2 ± 0.8 (5) | 1.5 ± 0.5 (5) | .12 |

| CD19+IgM+ | 57.0 ± 5.0 (3) | 55.8 ± 5.3 (4) | .87 |

| CD19+IgM- | 15.3 ± 3.2 (3) | 14.0 ± 2.9 (4) | .77 |

| CD19+AA4.1+ | 8.8 ± 1.0 (6) | 10.3 ± 0.7 (3) | .26 |

| CD19+AA4.1- | 64.8 ± 2.8 (6) | 66.0 ± 2.9 (3) | .78 |

| Thymus | |||

| CD4 SP | 10.7 ± 1.9 (6) | 13.8 ± 1.9 (5) | .28 |

| CD8α SP | 2.8 ± 0.9 (6) | 4.0 ± 0.6 (5) | .32 |

| CD4+CD8α+ | 77.0 ± 7.2 (6) | 67.2 ± 6.8 (5) | .35 |

| Lymph nodes | |||

| CD4 SP | 47.3 ± 3.3 (6) | 40.2 ± 5.4 (5) | .30 |

| CD8α SP | 21.0 ± 1.7 (6) | 18.4 ± 1.9 (5) | .34 |

| Peyer patches | |||

| CD4 SP | 23.9 ± 4.9 (7) | 45.4 ± 7.4 (8) | .03 |

| CD8α SP | 7.7 ± 1.6 (7) | 7.8 ± 1.4 (8) | .90 |

| B220+ | 69.7 ± 5.5 (7) | 25.5 ± 5.3 (8) | <.001 |

| B220+IgM+ | 40.0 (1) | 6.4 ± 1.5 (5) | NA |

| B220+IgD+ | 52.7 ± 10.0 (3) | ND | NA |

| B220+CD5+ | 15.0 ± 0.7 (4) | 13.1 ± 1.8 (5) | .40 |

| Peritoneal cavity | |||

| CD11b+ | 80.8 ± 4.4 (5) | 44.1 ± 8.4 (8) | <.01 |

| CD3ϵ+ | 19.2 ± 5.8 (5) | 21.1 ± 4.1 (7) | .80 |

| B220+ | 47.3 ± 2.7 (8) | 33.7 ± 9.0 (7) | .20 |

| B220+CD5+ | 12.5 ± 1.4 (4) | 3.9 ± 1.7 (5) | <.01 |

ND indicates not determined; NA, not applicable; and SP, single positive.

In the thymus, staining with anti-CD4 and anti-CD8α antibodies demonstrates normal development of α4 integrin–/– double-positive (77.0% ± 7.2% for wild-type and 67.2% ± 6.8% for α4 integrin–/–) and single-positive (SP) T-cell fractions of recipient mice (CD8α SP: 2.8% ± 0.9% for wild-type and 4.0% ± 0.6% for α4 integrin–/–; CD4 SP: 10.7% ± 1.9% for wild-type and 13.8% ± 1.9% for α4 integrin–/–) (Figure 6D). Likewise, in the lymph nodes α4 integrin–/– CD4 SP (40.2% ± 5.4%) and CD8α SP (18.4% ± 1.9%) fractions are represented equally to respective fractions of wild-type–derived donor cells (CD4 SP: 47.3% ± 3.3%; CD8α SP: 21.0% ± 1.7%) (Figure 6E and Table 2).

Colonization of the Peyer patches and peritoneal cavity is hindered by lack of α4 integrin

In contrast to other principal hematopoietic tissues, the contribution to both the Peyer patches and the peritoneal cavity is significantly reduced with α4 integrin–/– donor cells compared to wild-type cells (Figure 5B). This concerns both myeloid and lymphoid α4 integrin–/– populations (Figure 6F-G and Table 2). In the Peyer patches, the B220+ population is most affected, with its relative contribution being half as much as that observed from wild-type cells (69.7% ± 5.5% for wild-type; 25.5% ± 5.3% for α4 integrin–/–) (Figure 6F and Table 2). Mature B220+IgM+ α4 integrin–/– cells are substantially underrepresented (Figure 6F and Table 2), yet the B-1 (B220+CD5+) population (13.1% ± 1.8%) is comparable to wild-type B-1 percentages (15.0% ± 0.7%) (Figure 6F). By contrast, CD4 SP α4 integrin–/– cells are overrepresented (23.9% ± 4.9% for wild-type versus 45.4% ± 7.4% for α4 integrin–/–) (Figure 6F and Table 2). This, however, is only a relative value, since the overall colonization of Peyer patches is significantly reduced (Figure 5B). The percentage of CD8α SP α4 integrin–/– cells (7.8% ± 1.4%) is shown to be equivalent to wild-type donor cells (7.7% ± 1.6%) in this tissue (Figure 6F and Table 2).

Distribution of α4 integrin–/– and wild-type donor cell subsets in recipient tissues. Adult hematopoietic tissues of mice reconstituted with E12.5 embryonic tissues (AGM region, yolk sac, peripheral circulation, and fetal liver) of wild-type and α4 integrin–/– origin were analyzed by flow cytometry, and sample plots are given (see Table 2 for corresponding statistics. (A-C) Lymphoid (B220+ B-cell and CD3ϵ+ T-cell) and myeloid (CD11b/Gr1) populations for wild-type and α4 integrin–/– donor fractions of the peripheral blood (A), BM (B), and spleen (C) are illustrated. Mature B220+IgD+ and CD19+IgM+ B cells were produced by α4 integrin–/– HSCs in BM and spleen (B, C). Early α4 integrin–/– B cells expressing AA4.1 enter the spleen normally (C). (D,E) CD4/CD8α staining in the thymus (D) and lymph nodes (E) indicates normal T-cell development and distribution in α4 integrin–/– donor populations, as compared to wild-type T cells. (F,G) The inability of α4 integrin–/– cells to engraft the Peyer patches or peritoneal cavity is particularly apparent in the B-cell populations of these tissues. This is most noticeable in the mature B220+IgM+ population of the Peyer patches (F) and the B220+CD5+ B-1 cells of the peritoneal cavity (G).

Distribution of α4 integrin–/– and wild-type donor cell subsets in recipient tissues. Adult hematopoietic tissues of mice reconstituted with E12.5 embryonic tissues (AGM region, yolk sac, peripheral circulation, and fetal liver) of wild-type and α4 integrin–/– origin were analyzed by flow cytometry, and sample plots are given (see Table 2 for corresponding statistics. (A-C) Lymphoid (B220+ B-cell and CD3ϵ+ T-cell) and myeloid (CD11b/Gr1) populations for wild-type and α4 integrin–/– donor fractions of the peripheral blood (A), BM (B), and spleen (C) are illustrated. Mature B220+IgD+ and CD19+IgM+ B cells were produced by α4 integrin–/– HSCs in BM and spleen (B, C). Early α4 integrin–/– B cells expressing AA4.1 enter the spleen normally (C). (D,E) CD4/CD8α staining in the thymus (D) and lymph nodes (E) indicates normal T-cell development and distribution in α4 integrin–/– donor populations, as compared to wild-type T cells. (F,G) The inability of α4 integrin–/– cells to engraft the Peyer patches or peritoneal cavity is particularly apparent in the B-cell populations of these tissues. This is most noticeable in the mature B220+IgM+ population of the Peyer patches (F) and the B220+CD5+ B-1 cells of the peritoneal cavity (G).

In the peritoneal cavity, where α4 integrin–/– cell colonization also is severely lacking (Figure 5B), the CD11b+ population is substantially underrepresented (80.8% ± 4.4% for wild-type; 44.1% ± 8.1% for α4 integrin–/–) (Figure 6G and Table 2). Meanwhile, α4 integrin–/– CD3ϵ+ T cells (21.1% ± 4.1%) and B220+ B cells (33.7% ± 9.0%) are represented similarly to wild-type (CD3ϵ+: 19.2% ± 5.8%; B220+: 47.3% ± 2.7%). In contrast to B-cell distribution in the Peyer patches, α4 integrin–/– B220+CD5+ B-1 cells are scarce in the peritoneal cavity (only 3.9% ± 1.7% compared to 12.5% ± 1.4% for wild-type) (Figure 6G and Table 2).

α4 integrin–/– HSCs are able to reconstitute secondary recipients

We further assessed the properties of α4 integrin–/– HSCs by performing secondary transplantations. BM cells isolated from primary recipients were transplanted into secondary irradiated recipients (Figure 3). We found that α4 integrin–/– HSCs maintain their ability to home to and engraft principal hematopoietic organs and reconstitute the peripheral circulation of secondary recipients (Table 3). All mice (7 of 7) that received transplants of BM from primary recipients (E12.5 AGM and E12.5 FL primary donor tissues) were successfully reconstituted. Multilineage engraftment was confirmed in peripheral blood, BM, spleen, and thymus of secondary recipients using principal lymphoid and myeloid markers (data not shown).

Long-term repopulation of secondary irradiated recipients with α4 integrin–/– HSCs

. | Primary tissue, % . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|

. | E12.5 AGM region . | E12.5 fetal liver . | |

| Primary recipient PB | 35 | 51 | |

| Primary recipient BM | 11 | 14 | |

| Secondary recipient peripheral blood | |||

| 1.1 × 105 donor BM cells | ND | 3, 4 | |

| 2.2 × 105 donor BM cells | ND | 10 | |

| 5.5 × 105 donor BM cells | ND | 9, 14, 19 | |

| 1.4 × 106 donor BM cells | 14, 14, 14 | ND | |

. | Primary tissue, % . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|

. | E12.5 AGM region . | E12.5 fetal liver . | |

| Primary recipient PB | 35 | 51 | |

| Primary recipient BM | 11 | 14 | |

| Secondary recipient peripheral blood | |||

| 1.1 × 105 donor BM cells | ND | 3, 4 | |

| 2.2 × 105 donor BM cells | ND | 10 | |

| 5.5 × 105 donor BM cells | ND | 9, 14, 19 | |

| 1.4 × 106 donor BM cells | 14, 14, 14 | ND | |

Analysis of the peripheral blood of secondary recipients shows significant contribution of α4 integrin-/- cells 12 weeks after transplantation. Percentages indicate the level of contribution for each primary or secondary recipient, multiple numbers represent each mouse that received the corresponding secondary BM transplant.

PB indicates peripheral blood; BM, bone marrow; and ND, not done.

Discussion

Over many years a large body of evidence has accumulated that suggests important roles for VLA-4 (α4β1) and LPAM-1 (α4β7) receptor complexes in myelopoiesis and lymphopoiesis. Antibody blockade experiments in vitro and in vivo demonstrated the importance of α4 integrins in hematopoiesis, particularly in homing and differentiation. Targeted ablation of the α4 integrin genetic locus further confirmed the involvement of α4 integrins in hematopoietic development and differentiation. Although α4 integrin–/– myeloid and lymphoid progenitors are present and differentiate in the embryo, their differentiation becomes progressively corrupt through fetal into adult life,34,35 with α4 integrin–/– myeloid and B-lymphoid progenitors failing to complete differentiation unless they are cultured in vitro. It was proposed that these differentiation defects observed in the absence of α4 integrin are a result of restricted interaction of α4 integrin–/– cells with the hematopoietic stroma.34,35 In contrast, more recent studies on the conditional inactivation of α4 integrin in adult mice resulted in only minor changes in the BM, although increased long-term release of mutant progenitor cells into the peripheral blood was observed.37

These seemingly contradictory reports may have 2 alternative explanations: (1) the normal long-term execution of the myeloid and lymphoid differentiation program critically depends on α4 integrin-mediated interactions at some point during development prior to the adult stage, or (2) α4 integrin deficiency causes a competitive disadvantage of mutant versus wild-type cells co-developing in the [α4 integrin–/–: wt] chimeric animals used for analysis of differentiation of α4 integrin–/– cells.

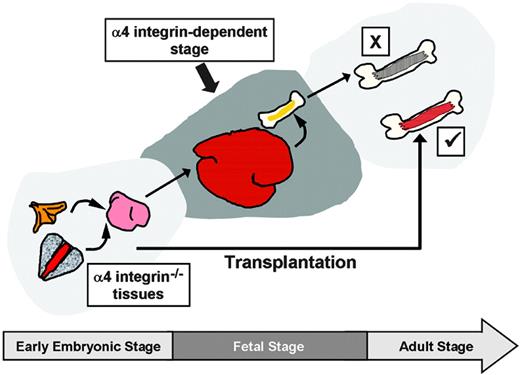

To explore these possibilities, our experiments were devised to allow us to test the differentiation capacity of α4 integrin–/– HSCs from the embryo when the fetal/neonatal period of development is bypassed, and in the presence of wild-type BM competitor cells (Figures 3, 7).

In initial analyses, we established that in general the proportion of recipients repopulated with α4 integrin–/– embryonic hematopoietic tissues tended to be slightly, but not significantly, lower as compared to the wild-type controls. This suggests that the number of HSCs developing in the early embryo in the absence of α4 integrin does not dramatically deviate from the wild-type pattern of HSC development. In accord with this, in vitro analysis also has demonstrated successful expansion of HSCs in the AGM region in the absence of α4 integrin. Although the overall level of hematopoietic contribution in individual recipients that received transplants of α4 integrin–/– tissues tended to be lower (especially in the yolk sac), repopulation was robust and stable over 1.5 years. The significance of the observed slightly substandard development and performance of α4 integrin–/– HSCs, as compared to wild-type HSCs, is unclear due to possible nonspecific effects caused by early embryonic lethality related to heart and placenta defects. Additionally, because we have not performed full-scale limiting dilution analyses, we are unable to conclude whether this minor defect is related to stem cell number or to a proliferative deficiency of HSCs. Whatever the reason for this minor underperformance, it is incomparable with the progressive and more dramatic failure of α4 integrin–/– cells in [α4 integrin–/–: wt] chimeric mice.34,35

We found also that the differentiation of transplanted α4 integrin–/– hematopoietic cells was not inhibited by the persistent presence of competitor wild-type cells. Except in the Peyer patches and peritoneal cavity, all tested donor-derived myeloid and lymphoid subsets were represented similarly to wild-type counterparts. We observed no quantitative difference in donor-derived myeloid CD11b/Gr1 subsets or lymphoid CD3ϵ+ and B220+ cells in the peripheral blood, BM, and spleens of animals that received α4 integrin–/– cells compared to those that received wild-type cells. The analysis of CD19+AA4.1+, CD19+IgM+, and B220+IgD+ subsets in recipient spleen and BM showed no difference in early or terminal B-cell differentiation (in [α4 integrin–/–: Rag–/–] chimeras, α4 integrin–/– mature B220+IgM+ cells in these tissues were severely deficient35,47 ). Similarly, on the basis of CD4 and CD8α staining in the thymus and lymph nodes, no aberrant T-cell differentiation patterns were observed in the absence of α4 integrin.

Requirements for α4 integrins throughout embryonic and adult hematopoiesis. A collective summary of works illustrates the requirements for α4 integrin, depending on developmental stage and context. When HSCs develop through the fetal stage into adulthood in the absence of α4 integrin, their differentiation program becomes progressively corrupt (pathway “X”).34,35 However, if the fetal stage is bypassed by transplanting early embryonic α4 integrin–/– HSCs directly into the adult, the hematopoietic deficiency is avoided (pathway “✓”). If normal hematopoiesis is established in the BM, α4 integrin ablation results in only minor defects (not shown).37 Cumulatively, these data suggest that during the fetal/neonatal stage(s) HSC development is strongly α4 integrin dependent.

Requirements for α4 integrins throughout embryonic and adult hematopoiesis. A collective summary of works illustrates the requirements for α4 integrin, depending on developmental stage and context. When HSCs develop through the fetal stage into adulthood in the absence of α4 integrin, their differentiation program becomes progressively corrupt (pathway “X”).34,35 However, if the fetal stage is bypassed by transplanting early embryonic α4 integrin–/– HSCs directly into the adult, the hematopoietic deficiency is avoided (pathway “✓”). If normal hematopoiesis is established in the BM, α4 integrin ablation results in only minor defects (not shown).37 Cumulatively, these data suggest that during the fetal/neonatal stage(s) HSC development is strongly α4 integrin dependent.

Thus, the reason for the dramatic failure of α4 integrin–/– cells in chimeric [α4 integrin–/–: wt] mice reported previously34,35 is unlikely to be a result of competition with wild-type cells. It is more likely that during fetal/neonatal development essential HSC/stroma α4 integrin-dependent interactions take place that may affect their survival, self-renewal, proliferative potential, and/or developmental homing.

In contrast to the BM, spleen, thymus, and lymph nodes, the relative repopulation of the Peyer patches by α4 integrin–/– cells was significantly compromised. This dramatic reduction in colonization of the Peyer patches with α4 integrin–/– cells is in line with previous reports suggesting a critical role for α4β7 integrins in recruiting lymphocytes to the Peyer patches.30-32 The development of Peyer patches in [α4 integrin–/–: wt] chimeric mice is completely disrupted, and Peyer patches are entirely absent in [α4 integrin–/–: Rag–/–] chimeras.35 Although we observed an overall dramatic reduction of α4 integrin–/– cells in the Peyer patches, the deficiency is most pronounced in the IgM+ B-cell compartment. The colonization of the peritoneal cavity with α4 integrin–/– cells also is significantly reduced. In this case, CD11b+ cells, representing the population of peritoneal macrophages, and B-1 (B220+CD5+) cells are most affected. Arroyo et al35 also reported a block in B-1 cells in the peritoneal cavity of [α4 integrin–/–: Rag–/–] chimeras. Since both α4 integrin–/– B cells and macrophages are present in normal numbers in other organs of reconstituted animals, the most likely explanation for their deficiency in Peyer patches and the peritoneal cavity is a poor ability for α4 integrin–/– cells to colonize these sites.

Collectively, the picture emerging from the present study and reports from other groups34,35,37 suggests differential requirements for α4 integrins throughout development of the hematopoietic system (summarized in Figure 7). It is proposed here that the differentiation potential of HSCs in the absence of α4 integrins dramatically deteriorates after the embryonic stage of development as a result of deficient interactions with the fetal/neonatal hematopoietic microenvironment.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, March 21, 2006; DOI 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4209.

Supported by an MRC Senior Fellowship (A.M.), an MRC Stem Cell Centre Development grant, the Leukaemia Research Fund, the Association for International Cancer Research, and the European Union Framework Programme VI (FPVI) integrated project EuroStemCell.

R.G. and L.H. contributed equally to this study.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We are grateful to Carolyn Manson, John Verth, Yvonne Gibson, and other members of the University of Edinburgh Animal House staff for taking care of our animals and for irradiations. We also would like to thank Jan Vrana for flow sorting and Antonius Rolink for informative discussion. We thank Samir Taoudi for helpful comments on the manuscript.

![Figure 1. α4 integrin expression in embryonic tissues and adult BM. Flow cytometrical analysis of α4 integrin coexpression with hematopoietic markers at key developmental stages. Dead cells were excluded using 7-AAD. Red blood cells were gated out for all adult bone marrow samples using forward scatter/side scatter plots, except where indicated (‡; all BM samples were unlyzed). Quadrants were placed according to appropriate isotype controls. (Collagenase-dispase treatment of BM produces similar staining patterns/intensities [data not shown].)](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/108/2/10.1182_blood-2005-10-4209/2/m_zh80140698690001.jpeg?Expires=1767744845&Signature=utQWjX-tN~Nn~3xIh02QxdLKUCn6qmIFz1NPDS5IKKY8~OfGCRah6lkMwU7-ZXndaxsDH5eDCzcuau5ok3mJOcdn2TYmOb8VRvAgOs8rKqUVrBHHcAWlxJF1bFs76DQ4SLUUyRqT7gl8UzWOrJPcairbE6Du04g3GjfsL0ke3au8T5-7BbkEE0JPtsCIGZc-k5DSP8E65Zh8Vli5V2-uaOCTafbU2tFJxPIG0nuAPfPALJQmVmpOnvs4TPBxQ4b660AkWCbacUo5-YmYoaKq~MiSIdUuKZ6JG3BJG~LWA0vC5xUekajPnrn05vXI0mSxnBUJoNftWbkoYXSFbnIBEg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal