Comment on Tardy et al, page 1492

Can approved drug dosing differ from that of clinical practice and expert opinion? This situation is increasingly apparent for lepirudin treatment of HIT, as highlighted by Tardy and colleagues in this issue of Blood.

The report by Tardy et al adds to others1-3 suggesting that the standard, approved dosing of lepirudin for treatment of HIT is too high. According to the prescribing information (Refludan; a recombinant hirudin; Berlex Laboratories, Wayne, NJ),3 recommended initial dosing (for serum creatinine level below 141 μM (or 1.6 mg/dL) is an intravenous bolus of 0.40 mg/kg body weight (maximal, 44 mg) followed by an intravenous infusion beginning at 0.15 mg/kg body weight/h (maximal initial rate, 16.5 mg/h), with subsequent dose adjustments based upon the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT; usual target, 1.5-2.5 times the median of the laboratory normal range).

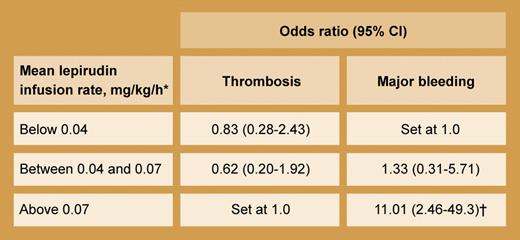

Relationship of mean lepirudin dose with thrombotic and bleeding outcomes (multivariate analysis using logistic regression model). *The mean (± SD) lepirudin infusion rate among the 181 patients in the study was 0.06 (± 0.04) mg/kg/h. †P = .003.

Relationship of mean lepirudin dose with thrombotic and bleeding outcomes (multivariate analysis using logistic regression model). *The mean (± SD) lepirudin infusion rate among the 181 patients in the study was 0.06 (± 0.04) mg/kg/h. †P = .003.

Current dosing guidelines of lepirudin evolved from large cardiologic clinical trials undertaken in the mid-1990s, which indicated a narrow therapeutic window for lepirudin.4 Several large phase III trials comparing heparin to hirudin (using bolus doses of 0.6 mg/kg and infusion rate of 0.2 mg/kg/h) in the postthrombolytic therapy setting were prematurely terminated due to excessive bleeding in the hirudin treatment arms.4 Subsequent clinical trials in patients with cardiac disease suggested that lepirudin dosing could be lowered to currently recommended levels without compromising antithrombotic efficacy.

Bleeding complications, however, remain a problem even with the standard dosing regimen. In this issue Tardy et al performed a retrospective observational study of 181 patients in France who received lepirudin for HIT. Thrombosis occurred in 13.8% of patients whereas major bleeding was seen in 20.4% (7 patients with fatal hemorrhage). Whereas lepirudin dose did not predict for thrombosis, it did for major bleeding (see table). Also, the mean dose given progressively declined from 1997 (0.09 mg/kg/h) to 2000 (0.06 mg/kg/h) to 2003 (0.04 mg/kg/h), suggesting a physician “learning curve” where the approved dose schedule was increasingly abandoned.

The study by Tardy and colleagues adds to the literature questioning the safety of approved lepirudin dosing. In a recent analysis of 3 historically controlled prospective cohort studies that led to regulatory approval of lepirudin for HIT, Lubenow and colleagues2 reported major bleeding in 20 (20.4%) of 98 patients while they received the standard dosing regimen. Moreover, renal function influenced bleeding risk: for serum creatinine level above 90 μM (or 1.0 mg/dL), major bleeding occurred in one third of patients, whereas the rate was only 10.8% (P < .001) for patients with serum creatinine levels below this threshold. Even when the initial infusion rate was set by study protocol, the mean rate given was only 0.11 mg/kg/h. These investigators also found in their study3 of lepirudin for HIT without thrombosis (starting infusion rate, 0.10 mg/kg/h, without initial bolus) that the mean lepirudin dose at end of treatment was only 0.06 mg/kg/h and that increased aPTT and serum creatinine levels were risk factors for bleeding. Progressive drug accumulation was apparent between 4 and 24 hours after starting lepirudin. Another smaller French study1 of 9 patients without major renal dysfunction who received standard lepirudin dosing found that only a low maintenance dose was needed (median, 0.04 mg/kg/h) to achieve therapeutic lepirudin plasma levels.

Consensus guidelines have generally mirrored official dosing schedules,5,6 although contributing experts have indicated preference for omitting the bolus and beginning lepirudin at a maximal rate of 0.10 mg/kg/h.7 Perhaps starting lepirudin at 0.05 to 0.075 mg/kg/h for patients with minor serum creatinine level elevation (90-140 μM, or 1.0-1.6 mg/dL) or for the elderly, checking aPTT levels every 4 hours until steady state is demonstrated, and aiming for a lower aPTT target range (1.5-2.0 times baseline) will also improve safety without compromising efficacy. It is unfortunate that package insert amendments usually require prospective assessment of dose alterations, when careful observational studies (such as Tardy et al and Hacquard et al1 ) and secondary analyses of prospective studies2,3 already justify changes in clinical practice. ▪

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal