VEGF therapy was shown to be effective for the treatment of ischemic vascular disease. However, possible adverse effects of such treatment continue to be debated.

Lucerna and colleagues show in this issue of Blood that proinflammatory effects of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) lead to the propagation of atherosclerosis and may contribute to destabilization of existing atherosclerotic plaques. Their data suggest that accelerated plaque growth occurred independently of VEGF-induced neovascularization, but was due to enhanced monocyte adhesion via VCAM-1 and P-selectin expression on endothelial cells.

VEGF-induced formation of atherosclerotic lesions could be problematic during therapeutic angiogenesis, especially in patients with established cardiovascular disease. Several studies have addressed this issue with varying, often contradictory results,1,2 possibly due to the use of different experimental models. Lucerna and colleagues address the question of how adenovirus-mediated, focal VEGF-A overexpression would affect atherosclerotic plaque progression in a developing lesion. Atherosclerosis was induced in an ApoE-deficient mouse on a high-fat diet by placing a silastic collar around the carotid artery, thereby changing flow patterns. This procedure does not involve endothelial injury per se, and atherosclerotic lesion formation is induced by disturbed flow conditions, resulting in progressive lesions after 4 weeks.3 In the current study, VEGF-A–encoding adenovirus was focally administered after 4.5 weeks, and the effect of local VEGF-A overexpression was studied after 2.5 weeks. The authors show that atherosclerotic lesion size was significantly increased in mice that had been treated with the VEGF-encoding adenovirus. Moreover, morphologic analysis indicated a preference for the formation of a more vulnerable plaque phenotype. It remains to be seen, however, whether the VEGF-treated atherosclerotic plaques were actually more prone to rupture.

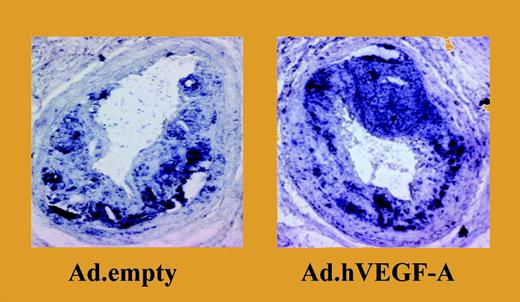

Overexpression of VEGF-A results in a significant increase in plaque size and in a marked accumulation of monocytes. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 122.

Overexpression of VEGF-A results in a significant increase in plaque size and in a marked accumulation of monocytes. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 122.

While neovascularization has been shown to cause plaque destabilization, Lucerna and colleagues demonstrate that VEGF overexpression creates a vulnerable plaque phenotype in the absence of increased angiogenesis. The authors observed, however, signifi-cant changes in the endothelial lining of the VEGF-treated vessels that are likely accompanied by increased permeability, which would facilitate infiltration of inflammatory cells.

The question remains as to whether the presumably more unstable phenotype would result from a direct action of VEGF or if it was secondary to increased inflammation. The authors suggest that VEGF treatment increased inflammation via autocrine and/or paracrine mechanisms, driving monocytic inflammation in an existing plaque. Studying the adhesive properties of treated vessels in an ex vivo perfusion model, they show that monocyte adhesion in VEGF-treated vessels occurs via VCAM-1 and PECAM-1, thereby identifying possible targets for cotherapy.

The possibility that VEGF can transform a silent lesion into a culprit lesion needs close attention. Adverse effects such as ongoing recruitment of inflammatory cells could be addressed by concomitant anti-inflammatory treatment. The authors suggest that cotherapy directed against endothelial adhesion molecules could prevent bystander effects of VEGF-A therapy, especially in patients with established cardiovascular disease. Another strategy would be anti-inflammatory cotreatment to locally block the impact of VEGF on undesirable signaling pathways, such as the NFκB pathway, with the advantage that not only proinflammatory cytokines would be inhibited, but also matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) that contribute to plaque destabilization. A recent study showed that combined treatment with hepatocyte growth factor and VEGF leads to down-regulation of the NFκB pathway and thus inhibition of VCAM expression.4

More studies like the one by Lucerna and colleagues are needed to finally devise successful treatment strategies for ischemic vascular disease in order to avoid the excessive vascular inflammation that may accompany VEGF treatment.

The authors declare no competing financial interests. ▪

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal