Abstract

Control of intensity and duration of erythropoietin (Epo) signaling is necessary to tightly regulate red blood cell production. We have recently shown that the ubiquitin/proteasome system plays a major role in the control of Epo-R signaling. Indeed, after Epo stimulation, Epo-R is ubiquitinated and its intracellular part is degraded by the proteasome, preventing further signal transduction. The remaining part of the receptor and associated Epo are internalized and degraded by the lysosomes. We show that β-Trcp is responsible for Epo-R ubiquitination and degradation. After Epo stimulation, β-Trcp binds to the Epo-R. This binding, like Epo-R ubiquitination, requires Jak2 activation. The Epo-R contains a typical DSG binding sequence for β-Trcp that is highly conserved among species. Interestingly, this sequence is located in a region of the Epo-R that is deleted in patients with familial polycythemia. Mutation of the serine residue of this motif to alanine (Epo-RS462A) abolished β-Trcp binding, Epo-R ubiquitination, and degradation. Epo-RS462A activation was prolonged and BaF3 cells expressing this receptor are hypersensitive to Epo, suggesting that part of the hypersensitivity to Epo in familial polycythemia could be the result of the lack of β-Trcp recruitment to the Epo-R.

Introduction

The glycoprotein hormone erythropoietin (Epo) regulates the proliferation, survival, and differentiation of erythroid progenitor cells leading to the tight control of red blood cell production (reviewed in Lacombe and Mayeux1 ). The Epo receptor (Epo-R) is a homodimer that belongs to the cytokine receptor superfamilly. Each Epo-R molecule of the dimer is constitutively associated with a Jak2 tyrosine kinase molecule that is absolutely required for Epo signaling.2–4 Association of Jak2 with the Epo-R is also necessary for Epo-R maturation and cell surface expression.5 Epo binding to its receptor induces a conformational change in the receptor complex that leads to Jak2 activation, subsequent phosphorylation of intracellular Epo-R Tyr residues, and activation of several intracellular signaling pathways, including Stat5, Ras/MAP kinase and PI3 kinase/Akt (reviewed by Damen et al6 ). At the same time, desensitization processes are activated. The tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 (SH2 domain-containing protein-tyrosine phosphatase-1) is recruited through phosphorylated Tyr 430 in human Epo-R and it dephosphorylates and deactivates Jak2.7 CIS/SOCS family members are produced upon Epo stimulation and Cis, Socs-1, and Socs-3 suppress Epo signaling through their binding to the Epo-R complex.8–10 Lastly, Epo and Epo-R are internalized and degraded.11–13 Epo-induced Epo-R down-regulation is a complex process that involves Epo-R ubiquitination, proteasomes, and lysosomes. Epo-R is rapidly ubiquitinated at the cell surface after Epo binding. This process occurs before receptor internalization and requires Jak2 kinase activity. Most of the Epo-R intracellular domain is then degraded by proteasomes. This degradation process removes all the phosphorylated tyrosine residues in the intracellular domain, thereby preventing further signal transduction. The remaining part of the Epo/Epo-R complex is internalized and degraded by the lysosomes.13 Thus, it appears that Epo-R ubiquitination plays a key role in Epo-R down-regulation during Epo stimulation. Previous attempts to identify the protein that mediates Epo-R ubiquitination have failed, and we have reported that neither Cbl nor SOCS 3 were involved in this process.13

Protein ubiquitination is catalyzed by 3 distinct enzymes. The ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1) activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent reaction and transfers ubiquitin to an ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, E2. This E2 enzyme, in cooperation with an E3 ubiquitin ligase, catalyzes the formation of an isopeptide bond between ubiquitin and the substrate. E3 ligases are responsible for substrate specificity in the ubiquitination reaction. Three families of E3 ligases can be distinguished: proteins with a HECT (homologous to E6-AP carboxyl terminus) catalytic domain, proteins with a RING finger domain, and proteins with a U box.14 RING domain E3s are further subdivided into 2 classes: 1) single peptide E3s, in which substrate recognition motifs and the RING finger reside within the same polypeptide, like E3 ligase Cbl; and 2) multiprotein E3 complexes like the SCF (Skp1-Cul1-F-box-protein) family of E3 ligases. β-Trcp 1 (β-transducin repeat-containing protein)15 and HOS/β-Trcp 216,17 are members of the F-box protein family. They interact with Skp1 through their F box motif and bind phosphorylated substrates through C-terminal WD40 repeats to ubiquitinate them. The specificity of these 2 forms of β-Trcp remains unclear and a redundant role of mammalian β-Trcp1 and HOS/β-Trcp2 in ubiquitination and degradation of IkB and β-catenin has been proposed on the basis of RNAi analysis and data from mice with genetic ablation of β-Trcp1.18,19 Typically, substrates of β-Trcp contain the DSG (X)2+n S destruction motif as found in IKBα or β-catenin proteins, and phosphorylation of the Ser residues in this motif is crucial for β-Trcp interaction and subsequent destruction. Moreover, Lys residues present in positions 9-13 upstream from this destruction motif have been described as preferentially chosen for ubiquitin conjugation. Indeed, Wu et al showed that the rate of ubiquitination depends on the proper positioning of the Lys in proximity for the ubiquitin transfer from E2 enzyme.20 Because the Epo-R contains a putative β-Trcp binding site in its intracellular domain, we tested whether β-Trcp proteins could be responsible for Epo-R ubiquitination on Epo stimulation.

Materials and methods

Reagents and cells

Recombinant human Epo (specific activity 120,000 U/mg) used throughout this study was a gift from Dr M. Brandt (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Penzberg, Germany). The proteasome inhibitor N-AC-Leu-Leu-norleucinal (LLnL) and the tyrphostin AG490 were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies (4G10) were from UBI (Lake Placid, NY). Anti-Epo-R (C-236) used in immunoprecipitation experiments were described previously.9 Anti-Epo-R used in Western blot experiments (C-20, batch K-200) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa-Cruz, CA). Anti-β-Trcp antibodies used in immunoprecipitations were a gift from Dr K. Strebel,15 and anti-β-Trcp antibodies used in Western blots were a gift from Dr S. Fuchs.21

Human UT-7 cells22 were cultivated in α−minimum essential medium containing 10% fetal calf serum complemented with 2 U/mL Epo. Before each experiment, the cells were serum and growth factor-deprived by overnight incubation in Iscove Dulbecco modified Eagle medium containing 0.4% deionized bovine serum albumin and 2 μg/mL iron-loaded human transferrin. Wild-type or mutant Epo-R transfected BaF3 cells were cultivated in RPMI containing 10% fetal calf serum complemented with 2 U/mL Epo. Before each experiment, the cells were Epo-starved by replacing the hormone with 2.5% WEHI-conditioned medium as a source of IL-3. WEHI-conditioned medium is the culture supernatant of WEHI 3B cells (ATCC TIB-68).

Plasmids

Human Epo-R cDNA was first subcloned in pCDNA3 vector (Invitrogen, Carslbad, CA) through polymerase chain reaction and site-directed mutagenesis carried out using QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The integrity of all constructs was confirmed by sequencing.

Whole-cell extracts, immunoprecipitation, and Western blotting

Whole cell extract preparation, immunoprecipitation, and Western blotting were performed as previously described.23 Polyacrylamide gels with an acrylamide/bis acrylamide ratio of 75/1 instead of 37.5/1 (C = 1.3% instead of 2.6% with C = 100 × concentration of bis-acrylamide/concentration of bis-acrylamide + acrylamide) were used to increase the electrophoretic shift of the phosphorylated Epo-R in some experiments (see figure legends).

Streptavidin precipitation

Cell lysates were incubated 1 hour at 4°C with neutravidin beads (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockfolk, IL). The beads were then washed twice in buffer A (1% NP40, 10 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM sodium chloride, 5 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 20 mM sodium fluoride, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate) and twice in buffer B (buffer A with 0.1% NP40 instead of 1%). Samples were boiled 5 minutes in Laemmli sample buffer.

Receptor measurement

Crosslinking studies

To crosslink 125I-Epo to surface and internalized receptors, the cells were incubated with 125I-Epo, washed to remove unbound Epo, and solubilized with 25 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EGTA, and 1% Nonidet P40 pH 8.00. The lysates were cleared by centrifugation and incubated for 20 minutes on ice with 2 mM BS3. The reaction was stopped by adding ethanolamine pH 8.00 to a final concentration of 0.1 M and the Epo-R complexes were immunoprecipitated using C-236 anti-Epo-R antibodies and Protein G Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK). Immunoprecipitated material was denatured by boiling in 10mM Tris, 1% SDS, and 50 mM DTT. DTT was removed by chromatography through G25 Sephadex spin columns. Recovered material was then diluted 10-fold with solubilization buffer and subjected to another immunoprecipitation using C-236 anti-Epo-R antibodies. Lastly, nonprecipitated 125I-Epo-crosslinked proteins were recovered by immunoprecipitation with anti-Epo antibodies.

Proliferation assays

Thymidine incorporation experiments were performed in a total volume of 100 μL per well. BaF3 cells at a concentration of 105cells/mL were seeded in triplicate in the presence of the indicated amounts of Epo in RPMI supplemented by 2.5% FCS. After 72 hours, 1 μCi of [3H] thymidine/well (Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA) was added for another 4 hours. The labeled cells were then harvested and the amount of DNA-incorporated radioactivity was quantified with a scintillation counter.

Results

β-Trcp interacts with Epo-R in a phosphorylation-dependent manner

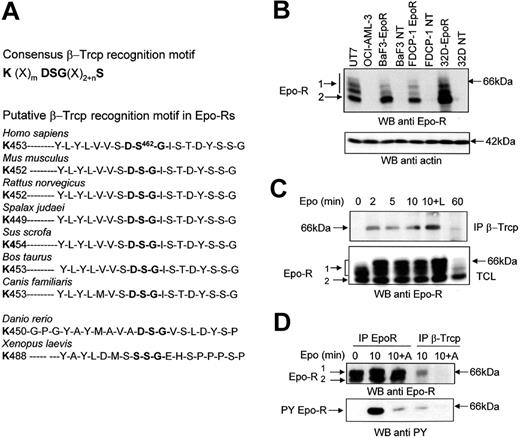

Sequence analysis of the Epo-R intracellular domain revealed the presence of a putative β-Trcp binding site. The sequence contains a typical DSG motif followed by several phosphorylable residues and preceded by a lysine residue that could potentially be ubiquitinated. This sequence is fully conserved in all mammalian Epo-R sequenced to date and in zebrafish Epo-R, thus suggesting it is important for the function of the protein. Only in Xenopus laevis does Epo-R appear to be significantly divergent from fish and mammalian Epo-Rs, and the DSG sequence is replaced by a SSG sequence (Figure 1A).

The association between Epo-R and β-Trcp is induced by Epo and requires Jak2 activity. (A) Consensus β-Trcp recognition motif and conserved β-Trcp recognition motif in Epo-Rs from different species. (B) Specificity of anti Epo-R antibodies. Total cell lysates were prepared from UT-7 cells, OCI-AML-3 cells, parental and Epo-R-transfected BaF3, FDCP-1, or 32D cells. Samples corresponding to 5 × 105 cells were analyzed by Western blot (WB) using SantaCruz C-20 (batch K-200) antibodies. The blot was then stripped and reprobed with anti-actin antibodies to ensure equal loading of the samples. (C) Epo-induced association between the Epo-R and β-Trcp. UT-7 cells were serum- and growth factor-starved for 18 hours and incubated for the indicated time with Epo (10 U/mL). Anti-β-Trcp immunoprecipitates and total cell lysates (TCL) were analyzed using anti-Epo-R antibodies. (D) Effect of Jak2 inhibition on the Epo-R/β-Trcp interaction. UT-7 cells were preincubated with AG490 for 15 minutes before stimulation with Epo for the indicated time. Anti-β-Trcp and anti-Epo-R immunoprecipitates were analyzed using antiphosphotyrosine (anti PY) and anti-Epo-R antibodies. Parts B and C: electrophoresis using C = 1.3% polyacrylamide gels.

The association between Epo-R and β-Trcp is induced by Epo and requires Jak2 activity. (A) Consensus β-Trcp recognition motif and conserved β-Trcp recognition motif in Epo-Rs from different species. (B) Specificity of anti Epo-R antibodies. Total cell lysates were prepared from UT-7 cells, OCI-AML-3 cells, parental and Epo-R-transfected BaF3, FDCP-1, or 32D cells. Samples corresponding to 5 × 105 cells were analyzed by Western blot (WB) using SantaCruz C-20 (batch K-200) antibodies. The blot was then stripped and reprobed with anti-actin antibodies to ensure equal loading of the samples. (C) Epo-induced association between the Epo-R and β-Trcp. UT-7 cells were serum- and growth factor-starved for 18 hours and incubated for the indicated time with Epo (10 U/mL). Anti-β-Trcp immunoprecipitates and total cell lysates (TCL) were analyzed using anti-Epo-R antibodies. (D) Effect of Jak2 inhibition on the Epo-R/β-Trcp interaction. UT-7 cells were preincubated with AG490 for 15 minutes before stimulation with Epo for the indicated time. Anti-β-Trcp and anti-Epo-R immunoprecipitates were analyzed using antiphosphotyrosine (anti PY) and anti-Epo-R antibodies. Parts B and C: electrophoresis using C = 1.3% polyacrylamide gels.

For Western blot analyses reported previously, we often used anti-Epo-R antibodies. A recent report has drawn attention to possible artifacts with anti-Epo-R antibodies.26 We also reported strong batch-to-batch variations among commercially available anti-Epo-R antibodies that did not allow us to definitely identify a suitable reagent for these analyses.27 Figure 1B shows that the anti-Epo-R antibodies used in our experiments specifically recognized Epo-R. Indeed, these antibodies did not recognize proteins in Epo-insensitive cell lines such as OCI-AML-3, a cell line derived from a patient with M4 FAB subtype leukemia,28 or untransfected BaF3, FDCP-1, or 32D murine cells. In contrast, after transfection with an expression vector encoding the human Epo-R, these cells became Epo-sensitive and expressed proteins recognized by Epo-R antibodies. Western blot analysis of Epo-R revealed the presence of 2 bands (Figure 1B, C, D). These 2 forms of Epo-R have been previously characterized.13 The higher band (66 kDa) is sensitive to endoglycanase F but resistant to endoglycanase H and corresponds to the mature form of Epo-R, which is expressed at the cell surface.13 On high-resolution gels, this band was separated into several bands (Figure 1B, C). It was partly shifted after Epo stimulation, because Epo stimulation induces a strong phosphorylation of its receptor (Figure 1D). Accordingly, treatment with alkaline phosphatase reversed this electrophoretic shift (data not shown). This band is referred to as Band1 throughout this article. In contrast, the lower molecular mass band (Band2; 64 kDa) is sensitive to endoglycanase H and corresponds to the maturing, endoplasmic reticulum form of the receptor.13,29 We first tested whether β-Trcp associated with Epo-R using UT-7 human erythroleukemic cells that express endogenous Epo-R. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments showed a specific interaction between the 2 endogenous proteins, Epo-R and β-Trcp (Figure 1C). Stimulation of UT-7 cells by Epo induced rapid and transient binding of β-Trcp to Epo-R. This interaction was maximal between 2 and 10 minutes, and it was greatly reduced after 60 minutes of stimulation. The presence of the proteasome inhibitor LLnL that protects Epo-Rs from degradation12,13 increased the association between the 2 proteins. It is noticeable that β-Trcp bound exclusively to the cell surface expressed Epo-R and that β-Trcp association with Epo-R was regulated by Epo stimulation (Figure 1C). The decreased binding of β-Trcp after 60 minutes of Epo stimulation is the result of the strong down-regulation of the mature form of Epo-R that occurs after prolonged stimulation with Epo.13

To test whether phosphorylation of the receptor was required for interaction, we used tyrphostin AG490, which has been shown to inhibit Jak2 activity.30 Western blot analysis of anti-Epo-R immunoprecipitates showed that blocking Jak2 activity strongly decreased Epo-R Tyr phosphorylation (Figure 1D, lower panel) and also blocked Epo-R/β-Trcp interaction (Figure 1D, upper panel). Moreover, this experiment revealed that at least a portion of Epo-R that associated with β-Trcp was tyrosine phosphorylated. Overall, these results show that β-Trcp associated with Epo-R after Epo stimulation and that Jak2 activation was necessary for β-Trcp to interact with Epo-R.

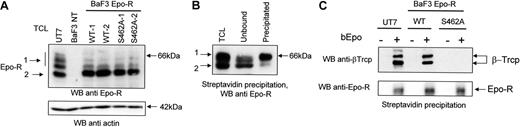

Ser 462 of Epo-R is crucial for interaction

We next investigated whether the putative β-Trcp recognition motif within the cytoplasmic domain of Epo-R is required for interaction between Epo-R and β-Trcp. Because the first Ser in the recognition motif is usually necessary for the binding of β-Trcp to its ligands (IKBα, β-catenin 31 ), we mutated Ser462 in human Epo-R to alanine. cDNAs encoding Epo-RWT or Epo-RS462A were stably transfected into BaF3 cells. Two independent transfections were performed and 3 clones expressing each receptor form were randomly selected for this study. 125I-Epo binding was used to quantify Epo-R cell surface expression. Three independent determinations were performed for each clone. The cell surface expression of Epo-R was not significantly different in BaF3 cells expressing Epo-RWT (1912 +/−231 Epo binding sites/cell) or Epo-RS462A (2515 +/−414 Epo binding sites/cell). Western blot analysis showed that, in BaF3 cells expressing either Epo-RWT or Epo-RS462A, most Epo-R presented a molecular mass of 64 kDa (Figure 2A, Band2), characteristic of the maturing form present in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), whereas in UT7 cells, most endogenous Epo-R were processed to the 66 kDa form present at the cell surface (Band1). Thus, as previously described,29 overexpression of transfected Epo-R cDNA leads to the expression of a limited number of cell surface Epo-R and most synthesized receptors remain inside the cells and do not reach the cell surface.

Importance of the Ser 462 of Epo-R for interaction with β-Trcp. (A) Expression of Epo-R in UT-7 cells and in Epo-R-transfected BaF3 cells. Total cell lysates prepared from UT-7 cells, untransfected BaF3 cells, and BaF3 Epo-RWT cells no. 1 and no. 2, BaF3 Epo-RS462Acells no. 1 and no. 2, were analyzed by Western blot (WB) using a C = 1.3% polyacrylamide gel and anti-Epo-R antibodies. The blot was then stripped and reprobed with anti-actin antibodies to ensure equal loading of the samples. (B) Cell surface Epo-R is quantitatively precipitated by streptavidin after bEpo binding. Starved UT-7 cells were stimulated for 10 minutes with 10 U/mL bEpo. Cells were lysed using NP40 1% and lysates were cleared by centrifugation (27,000 g, 20 minutes). Clarified lysates were then precipitated with streptavidin beads. Extracts before streptavidin precipitation (TCL), unbound material, and material precipitated by streptavidin, each corresponding to 5 × 105 cells, were analyzed by Western blot using anti-Epo-R antibodies. (C) Ser 462 of Epo-R is required for β-Trcp binding. After Epo deprivation as described in “Materials and methods,” UT7, BaF3 Epo-RWT, and BaF3 Epo-RS462A cells were stimulated or not with biotinylated Epo (bEpo). Clarified lysates were precipitated with streptavidin beads and the precipitates were analyzed by Western blot using anti-β-Trcp and anti-Epo R antibodies.

Importance of the Ser 462 of Epo-R for interaction with β-Trcp. (A) Expression of Epo-R in UT-7 cells and in Epo-R-transfected BaF3 cells. Total cell lysates prepared from UT-7 cells, untransfected BaF3 cells, and BaF3 Epo-RWT cells no. 1 and no. 2, BaF3 Epo-RS462Acells no. 1 and no. 2, were analyzed by Western blot (WB) using a C = 1.3% polyacrylamide gel and anti-Epo-R antibodies. The blot was then stripped and reprobed with anti-actin antibodies to ensure equal loading of the samples. (B) Cell surface Epo-R is quantitatively precipitated by streptavidin after bEpo binding. Starved UT-7 cells were stimulated for 10 minutes with 10 U/mL bEpo. Cells were lysed using NP40 1% and lysates were cleared by centrifugation (27,000 g, 20 minutes). Clarified lysates were then precipitated with streptavidin beads. Extracts before streptavidin precipitation (TCL), unbound material, and material precipitated by streptavidin, each corresponding to 5 × 105 cells, were analyzed by Western blot using anti-Epo-R antibodies. (C) Ser 462 of Epo-R is required for β-Trcp binding. After Epo deprivation as described in “Materials and methods,” UT7, BaF3 Epo-RWT, and BaF3 Epo-RS462A cells were stimulated or not with biotinylated Epo (bEpo). Clarified lysates were precipitated with streptavidin beads and the precipitates were analyzed by Western blot using anti-β-Trcp and anti-Epo R antibodies.

Because β-Trcp binds to the mature, cell surface Epo-R in UT-7 cells after Epo stimulation (Figure 1), we purified the fraction of cell surface-expressed Epo-R to eliminate possible artifacts resulting from the high amount of Epo-R present inside Epo-R-transfected cells. Indeed, proteins that are not correctly processed can be ubiquitinated inside the cells and degraded by the proteasomes (see Hirsch et al32 for a recent review). For cell surface Epo-R purification, we used Epo that had been biotinylated on the sialic acid residues to maintain full biologic activity (bEpo).33 Preliminary experiments showed that the cell surface form of Epo-R (Band1) was efficiently precipitated by streptavidin after bEpo binding (Figure 2B). UT7 cells, Epo-RWT, and Epo-RS462A BaF3 cells were stimulated with bEpo or not, cells were solubilized, and bEpo and associated proteins were precipitated using streptavidin beads. Western blot analysis of the immunoprecipitates using anti-Epo-R antibodies showed that cell surface Epo-R have been efficiently coprecipitated (Figure 2C, lower panel). Probing the blots with anti-β-Trcp antibodies showed the association of β-Trcp with Epo-R in cells expressing Epo-RWT but not Epo-RS462A (Figure 2C, upper panel). We always observed 2 bands in β-Trcp immunoblots. Similar results have been previously published,34,35 and these bands probably correspond to the 2 β-Trcp isoforms, β-Trcp1 and 2. Thus, the replacement of the Ser 462 by an Ala completely abolished the interaction between β-Trcp and Epo-R, demonstrating that this amino acid is crucial for binding.

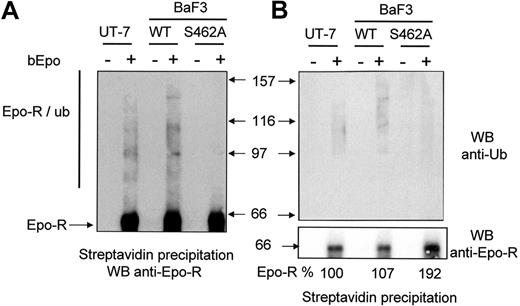

β-Trcp /Epo-R interaction is required for Epo-R ubiquitination

We next examined the ubiquitination of Epo-RWT and Epo-RS462A. We used LLnL to avoid rapid degradation of ubiquitinated Epo-R. We have previously shown that LLnL, which inhibits both proteasome and cathepsin B proteolytic activities, protected Epo-R from degradation by proteasomes and lysosomes.12 BaF3 cells were preincubated with LLnL for 15 minutes and bEpo was added to cell samples for 30 minutes. Cells were solubilized, and Epo-R complexes were precipitated using streptavidin beads and analyzed by Western blot using anti-Epo-R antibodies (Figure 3A) or anti-ubiquitin antibodies (Figure 3B). The smears with high molecular mass are the signature of Epo-R ubiquitinated forms13 and they were strongly detected in UT-7 cells and in Epo-RWT BaF3 cells. Few if any ubiquitinated forms of Epo-RS462A were detectable. To compare the quantity of precipitated Epo-R, the membrane was stripped and reprobed with anti-Epo-R antibodies (Figure 3B, lower panel). The intensity of the band corresponding to Epo-R was quantified by densitometry. Similar amounts of Epo-R were precipitated from the different cell lines using bEpo and streptavidin, whereas no Epo-R was precipitated from cells unstimulated by bEpo, showing that Epo-R precipitation by streptavidin was specific. Altogether, these results demonstrate that Ser 462 within the β-Trcp recognition motif of Epo-R is required for β-Trcp recruitment and Epo-R ubiquitination.

Role of the Ser 462 of Epo-R for Epo-R ubiquitination. (A) After Epo deprivation as described in “Materials and methods,” UT7, BaF3 Epo-RWT, and BaF3 Epo-RS462A cells were stimulated or not with biotinylated Epo (bEpo). Cells were lysed using 1% NP40 and lysates were cleared by centrifugation (27,000g for 20 minutes). Lysates were then precipitated with streptavidin and the precipitates were analyzed by Western blot (WB) using anti-Epo-R antibodies. Ubiquitinated forms of Epo-R are indicated (Epo-R/ub). (B) Same experiments as part A; precipitates were analyzed by an anti-ubiquitin antibody (anti-Ub, upper panel) or an anti-Epo-R antibody (C-20, lower panel). Images were recorded using a Fuji Las3000 camera and quantification of the Epo-R was performed using Multigauge V3.0 software (FujiFilm).

Role of the Ser 462 of Epo-R for Epo-R ubiquitination. (A) After Epo deprivation as described in “Materials and methods,” UT7, BaF3 Epo-RWT, and BaF3 Epo-RS462A cells were stimulated or not with biotinylated Epo (bEpo). Cells were lysed using 1% NP40 and lysates were cleared by centrifugation (27,000g for 20 minutes). Lysates were then precipitated with streptavidin and the precipitates were analyzed by Western blot (WB) using anti-Epo-R antibodies. Ubiquitinated forms of Epo-R are indicated (Epo-R/ub). (B) Same experiments as part A; precipitates were analyzed by an anti-ubiquitin antibody (anti-Ub, upper panel) or an anti-Epo-R antibody (C-20, lower panel). Images were recorded using a Fuji Las3000 camera and quantification of the Epo-R was performed using Multigauge V3.0 software (FujiFilm).

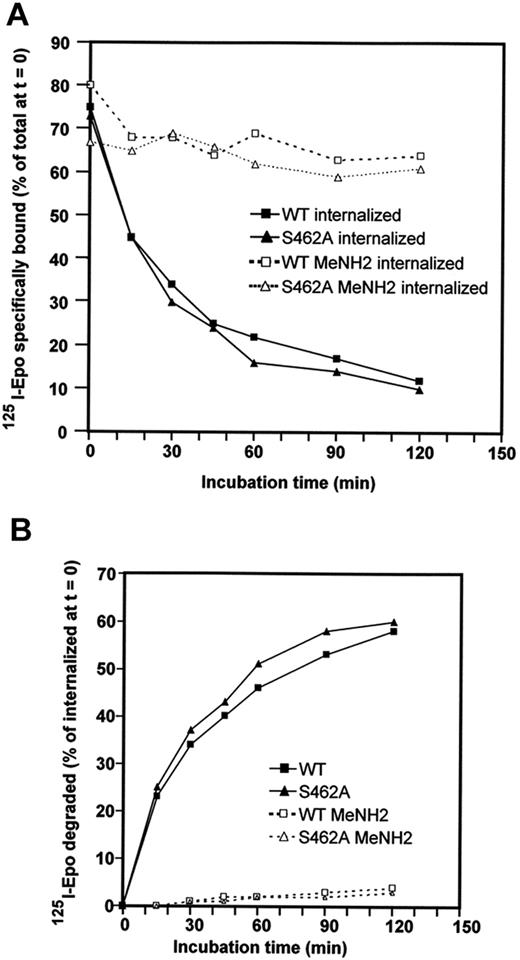

Epo/Epo-R routing to lysosomes does not require β-Trcp binding

Ubiquitin can provide different signals for the targeted protein to which it is attached, such as signals for proteasomal degradation or signals for receptor endocytosis and degradation by lysosomes.14,36 After Epo binding to Epo-R, Epo-Epo-R complexes are internalized and routed to the lysosomes for degradation. We tested whether β-Trcp recruitment to Epo-R was also required for Epo-Epo-R routing to the lysosomes. In contrast to Epo-R, which is degraded by both lysosomes and proteasomes, Epo remains associated with Epo-R and is only degraded by lysosomes.13 Routing of Epo-Epo-R complexes to the lysosomes was tested by measuring the degradation of internalized Epo. BaF3 cells expressing Epo-RWT or Epo-RS462A were preincubated for 45 minutes with radiolabeled Epo (125I-Epo) and washed to remove free iodinated Epo. Incubation at 37°C was followed and the amount of internalized 125I-Epo was determined at the indicated time (Figure 4A). Degradation of 125I-Epo released in the culture medium was tested by TCA precipitation (Figure 4B). 125I-Epo internalization was similar in BaF3 cells expressing Epo-RWT and Epo-RS462A (see legend of Figure 4). TCA-soluble radioactivity appeared in the culture medium of cells expressing each receptor with exactly the same kinetics, demonstrating that Epo degradation did not require β-Trcp binding to Epo-R. To ascertain that Epo degradation was attributable to lysosomes in each case, cells were incubated with methylamine, a classic inhibitor of lysosomal activity. Undegraded Epo molecules accumulated inside methylamine-treated cells and no TCA-soluble radioactivity was detected in the culture medium, confirming our previously published results that Epo degradation was attributable to lysosomes. Thus, β-Trcp binding to Epo-R is not required for Epo targeting to the lysosomes.

Role of Ser 462 of the cytoplasmic domain in Epo/Epo-R routing to lysosomes. (A) BaF3 cells expressing Epo-RWT or Epo-RS462A were preincubated for 45 minutes with radiolabeled Epo. Cells were washed to remove free iodinated Epo; Epo bound at the cell surface and internalized were then determined. The cells were resuspended in culture medium containing an excess of unlabeled Epo to avoid rebinding of dissociated125I-Epo molecules and incubated at 37°C. At the indicated times, cells were sampled and radioactivity present at the cell surface and inside the cells was measured as previously described.13 BaF3 cells expressing Epo-RWT had accumulated 23,600 cpm/106 cells inside the cells after 45 minutes of preincubation, while BaF3 cells expressing Epo-RS462A had accumulated 29,300 cpm/106 cells in the reported experiment. (B) Degradation of125I-Epo released in the culture medium was tested by TCA precipitation with soluble radioactivity corresponding to degraded Epo. Experiments were performed in the absence (full lines) or in the presence (dotted lines) of methylamine (MeNH2).

Role of Ser 462 of the cytoplasmic domain in Epo/Epo-R routing to lysosomes. (A) BaF3 cells expressing Epo-RWT or Epo-RS462A were preincubated for 45 minutes with radiolabeled Epo. Cells were washed to remove free iodinated Epo; Epo bound at the cell surface and internalized were then determined. The cells were resuspended in culture medium containing an excess of unlabeled Epo to avoid rebinding of dissociated125I-Epo molecules and incubated at 37°C. At the indicated times, cells were sampled and radioactivity present at the cell surface and inside the cells was measured as previously described.13 BaF3 cells expressing Epo-RWT had accumulated 23,600 cpm/106 cells inside the cells after 45 minutes of preincubation, while BaF3 cells expressing Epo-RS462A had accumulated 29,300 cpm/106 cells in the reported experiment. (B) Degradation of125I-Epo released in the culture medium was tested by TCA precipitation with soluble radioactivity corresponding to degraded Epo. Experiments were performed in the absence (full lines) or in the presence (dotted lines) of methylamine (MeNH2).

Epo-R cleavage by proteasome is dependent on β-Trcp association

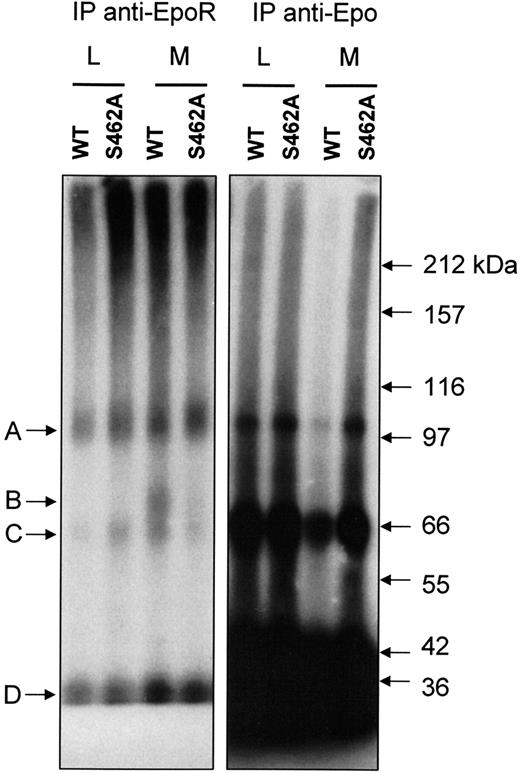

We have previously shown that the intracellular domain of the cell surface Epo-R is partially degraded by the proteasome after ubiquitination.13 We asked whether a mutated Epo-R, unable to bind β-Trcp, can still be degraded by the proteasome. Because no antibody recognizing the extracellular domain of the receptor in Western blot is currently available,13,26 we used chemical crosslinking experiments to covalently link 125I-Epo to Epo-R to detect the degradation products. After denaturation, Epo-R was immunoprecipitated using an anti-Epo-R antibody (C-236) that recognized the membrane proximal domain of Epo-R. This method has been described extensively in Walrafen et al.13 Briefly, BaF3 cells expressing either Epo-RWT or Epo-RS462A were preincubated with LLnL or methylamine for 15 minutes and stimulated for 30 minutes with 125I-Epo. LLnL protects Epo-R from degradation by both lysosomes and proteasomes, whereas methylamine inhibits lysosomal degradation only. The cells were solubilized and proteins were crosslinked using BS3. Epo-R was immunoprecipitated, precipitates were denatured by boiling in sodium dodecyl sulfate, and subsequently immunoprecipitated again with anti-Epo-R antibody (C-236).

Four bands (A, B, C, D) were detected by autoradiography in extracts of methylamine-treated BaF3 cells expressing Epo-RWT. The same bands have been previously observed in UT-7 cell extracts.13 As previously described by Walrafen et al, Band A corresponds to full-length Epo-R (66 kDa) linked to 125I-Epo (34 kDa) and band B corresponds to C-terminus truncated Epo-R (40 kDa) linked to 125I-Epo. Band C corresponds to an unknown protein linked to 125I Epo, and band D is free 125I-Epo. Accordingly, most of bands A and B were precipitated by anti-Epo-R C-236 antibodies after denaturation, demonstrating that they were directly recognized by the antibodies. Most of bands C and D were not precipitated by anti-Epo-R antibodies (Figure 5, left panel) and were recovered using anti-Epo antibodies (Figure 5, right panel). As previously reported for UT-7 cells, when proteasome and lysosome activities were blocked by LLnL, no band B was detected in BaF3 cells expressing Epo-RWT or Epo-RS462A. When lysosome activity alone was blocked, band B was observed only in BaF3 cells expressing Epo-RWT. No band corresponding to a C-terminus truncated form of the Epo-R was detectable in BaF3 cells expressing an Epo-RS462A even after long exposure. These results strongly suggest that the Ser 462 in the destruction motif is crucial for Epo-R C-terminus degradation by proteasome.

Protection from proteasomal degradation of Epo-RS462A. BaF3 cells expressing either Epo-RWT or Epo-RS462A were preincubated with LLnL (L) or methylamine (M) for 15 minutes and stimulated for 30 minutes with125I-Epo. After washing to remove unbound radioactivity, the cells were lysed, and clarified cell extracts were crosslinked with 2 mM of BS3. Excess crosslinking reagent was blocked with ethanolamine, and Epo-R was precipitated with a polyclonal antibody directed against the intracellular domain of the receptor (C-236). Precipitates were denatured by boiling in sodium dodecyl sulfate and subsequently immunoprecipitated again with the same antibody (left panel). Lastly, nonprecipitated125I-Epo-crosslinked proteins were recovered by immunoprecipitation with anti-Epo antibodies (right panel). Experiment analysis was performed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography.

Protection from proteasomal degradation of Epo-RS462A. BaF3 cells expressing either Epo-RWT or Epo-RS462A were preincubated with LLnL (L) or methylamine (M) for 15 minutes and stimulated for 30 minutes with125I-Epo. After washing to remove unbound radioactivity, the cells were lysed, and clarified cell extracts were crosslinked with 2 mM of BS3. Excess crosslinking reagent was blocked with ethanolamine, and Epo-R was precipitated with a polyclonal antibody directed against the intracellular domain of the receptor (C-236). Precipitates were denatured by boiling in sodium dodecyl sulfate and subsequently immunoprecipitated again with the same antibody (left panel). Lastly, nonprecipitated125I-Epo-crosslinked proteins were recovered by immunoprecipitation with anti-Epo antibodies (right panel). Experiment analysis was performed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography.

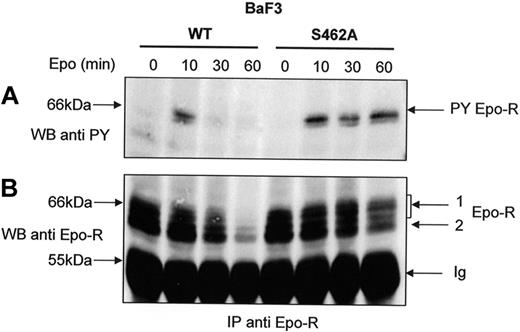

Epo-RS462A activation is prolonged

The degradation of the Epo-R C-terminus domain by the proteasome is dependent on β-Trcp-mediated ubiquitination (Figure 5) and leads to the elimination of all the Tyr residues of the cytoplasmic domain important for Epo-R signaling. We hypothesized that a prolonged Epo-R tyrosine phosphorylation should be detected with Epo-RS462A after Epo stimulation because its cytoplasmic tail was not degraded. Cells were pretreated with cycloheximide to decrease the intracellular pool of maturing receptors that could replenish the cell surface pool of Epo-R during prolonged Epo stimulation. We observed that tyrosine phosphorylation of Epo-RS462A persisted even after 60 minutes of Epo stimulation. In contrast, Epo-RWT activation rapidly decreased after 30 minutes of hormone stimulation (Figure 6A). Reprobing the blot with an anti-Epo-R (C20) antibody confirmed that the same amount of Epo-R was precipitated in cells expressing the WT or the mutated receptor after short incubation times with Epo. After prolonged hormone stimulation, cell surface-expressed Epo-RWT disappeared more rapidly than Epo-RS462A, confirming that Epo-RS462A is largely resistant to degradation. Thus, our data demonstrate that Epo-RS462A, insensitive to proteasome degradation, harbors a prolonged activation after Epo stimulation.

Sustained tyrosine phosphorylation of Epo-RS462A. BaF3 cells expressing either Epo-RWT or Epo-RS462A were preincubated with cycloheximide for 30 minutes and stimulated with Epo for the indicated times. Anti-Epo-R immunoprecipitations (IP) using C-236 anti-Epo-R antibodies were analyzed by Western blot using an antiphosphotyrosine (anti-PY) antibody (A) or anti-Epo-R (C-20) antibody (B) and a C = 1.3% polyacrylamide gel. PY Epo-R: tyrosine-phosphorylated Epo-R, Ig: immunoglobulin heavy chains.

Sustained tyrosine phosphorylation of Epo-RS462A. BaF3 cells expressing either Epo-RWT or Epo-RS462A were preincubated with cycloheximide for 30 minutes and stimulated with Epo for the indicated times. Anti-Epo-R immunoprecipitations (IP) using C-236 anti-Epo-R antibodies were analyzed by Western blot using an antiphosphotyrosine (anti-PY) antibody (A) or anti-Epo-R (C-20) antibody (B) and a C = 1.3% polyacrylamide gel. PY Epo-R: tyrosine-phosphorylated Epo-R, Ig: immunoglobulin heavy chains.

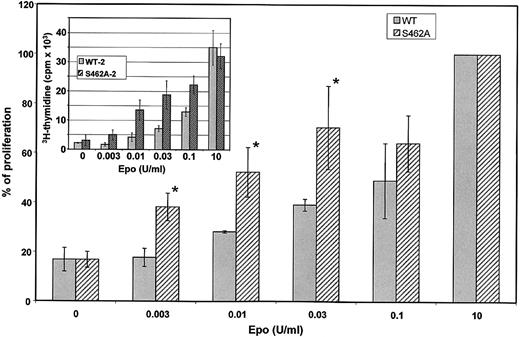

BaF3 cells expressing an Epo-R unable to bind β-Trcp are hypersensitive to Epo

Because activation of Epo-RS462A is prolonged on Epo stimulation compared with Epo-RWT, cells expressing the Epo-RS462A mutant could gain a growth advantage. We compared Epo sensitivity of BaF3 cells expressing Epo-RWT or Epo-RS462A. Cell proliferation of 3 different BaF3 clones expressing Epo-RS462A and 3 different BaF3 clones expressing wild-type (WT) receptors was tested by 3H-thymidine incorporation in 3 independent experiments (Figure 7). A typical experiment is shown in the insert of Figure 7. To allow comparison between independent experiments, data were normalized to maximal 3H-thymidine incorporation observed using a saturating concentration of Epo (Figure 7, main graph). None of these BaF3 cells proliferated in the absence of growth factor. Proliferation of all BaF3 cell clones expressing either Epo-RWT or Epo-RS462A was similar at saturating concentrations of Epo (Figure 7, insert) or IL-3 (data not shown). In contrast, at low Epo concentrations (between 3 and 30 mU/mL), cells expressing the Epo-RS462A mutant proliferated more rapidly than cells expressing wild-type Epo-Rs. Thymidine incorporation results were verified by counting viable cells in the presence of tryptan blue dye (data not shown), confirming that increased thymidine incorporation was the result of enhanced cell proliferation. Thus, expression of an Epo-R unable to bind β-Trcp allowed cells to proliferate more efficiently at low doses of Epo that indeed correspond to physiological doses of circulating Epo. These data indicate that the recruitment of β-Trcp to the Epo-R is important to negatively regulate the proliferative signal induced by the hormone.

Hypersensitivity of BaF3 cells expressing an Epo-R unable to bind β-Trcp. Three independent BaF3 clones expressing Epo-RWT and 3 independent BaF3 clones expressing Epo-RS462A were tested for Epo sensitivity by 3H-thymidine incorporation. Cells were grown 3 days with the indicated concentration of Epo before measuring 3H-thymidine incorporation. Inset shows the results of a typical experiment. Each cell clone was tested in 3 independent experiments. To allow comparison between experiments, maximum 3H-thymidine incorporation, which was always obtained in incubations with 10 U/mL Epo, was set at 100 for each cell line in each experiment and 3H-thymidine incorporation observed using lower Epo concentrations was expressed relative to this value. The main graph depicts the results of the 9 determinations and error bars represent standard deviations. The asterisk indicates a P value < 0.05 by Student t.

Hypersensitivity of BaF3 cells expressing an Epo-R unable to bind β-Trcp. Three independent BaF3 clones expressing Epo-RWT and 3 independent BaF3 clones expressing Epo-RS462A were tested for Epo sensitivity by 3H-thymidine incorporation. Cells were grown 3 days with the indicated concentration of Epo before measuring 3H-thymidine incorporation. Inset shows the results of a typical experiment. Each cell clone was tested in 3 independent experiments. To allow comparison between experiments, maximum 3H-thymidine incorporation, which was always obtained in incubations with 10 U/mL Epo, was set at 100 for each cell line in each experiment and 3H-thymidine incorporation observed using lower Epo concentrations was expressed relative to this value. The main graph depicts the results of the 9 determinations and error bars represent standard deviations. The asterisk indicates a P value < 0.05 by Student t.

Discussion

Several cytokine receptors are ubiquitinated at the plasma membrane and a direct involvement of ubiquitination in the down-regulation of some of them has been demonstrated.13,37–41 The data presented here demonstrate the role of ubiquitination of Epo-R in the ligand-induced down-regulation of the cell surface-expressed receptors. After Epo stimulation, Epo-R is phosphorylated and subsequently ubiquitinated. We show here that β-Trcp binds to the Ser 462 within the intracellular part of the receptor and contributes to Epo-R ubiquitination in the presence of the hormone. The ubiquitination mediated by β-Trcp is a crucial signal for the C-terminus degradation of Epo-R because point mutation of the Ser 462 blocks Epo-R ubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome, thereby leading to sustained activation of Epo-RS462A. In contrast, ubiquitination by β-Trcp is not necessary for targeting the Epo/Epo-R complex to lysosomes. Furthermore, our results show that β-Trcp-mediated ubiquitination is important for Epo-induced cellular responses like cell proliferation. Indeed, BaF3 cells expressing a mutated Epo-R unable to bind β-Trcp are hypersensitive to Epo.

Two other members of the cytokine receptor family, IFNAR1, a subunit of the interferon alpha receptor,37 and the prolactin receptor (Prl-R),38 also associate with β-Trcp in a ligand-dependent manner and are ubiquitinated through this association. Although these receptors are also down-regulated through β-Trcp-induced ubiquitination, the mechanisms appear to be fully different for these receptors and for the Epo-R. Indeed, ubiquitination of IFNAR1 and Prl-R by β-Trcp provides internalization and lysosome-targeting signals, whereas ubiquitination of Epo-R by β-Trcp leads to the degradation of the receptors by proteasomes but does not affect lysosomal targeting of the activated receptors. Although the role of ubiquitination in providing a sorting signal for internalized receptors to lysosomes is relatively well documented, few receptors have been shown to be degraded at the cell surface by proteasomes after ubiquitination. In addition to Epo-R, the intracellular domain of the IL-3 receptor β chain is also degraded by the proteasomes at the cell surface.42 The mechanisms that control this degradation are not known. Protein decoration by ubiquitin can provide different signals depending on the type of ubiquitin binding to the target protein. Internalization and lysosomal targeting signals are provided by monoubiquitination43 and/or the binding of polyubiquitin chains linked through Lys63 of the ubiquitin molecule,44 whereas protein targeting to the proteasomes involves polyubiquitin chains linked through Lys48 of the ubiquitin molecule. Interestingly, the same E3 ligases are generally able to provide both types of signals depending on the substrate molecule. Cbl is able to provide both lysosomal targeting signals for several tyrosine kinase receptors and proteasome degradation signals for intracellular proteins such as Lyn or Fyn.45 Similarly, β-Trcp can provide both lysosome targeting signals to PrlR and the interferon-α receptor and proteasome degradation signals to β-catenin and IκB. Our results show that the subcellular localization of the target protein does not confer the specificity of the type of ubiquitin modification since β-Trcp ubiquinates Epo-R in a manner that targets it for proteasome degradation.

Epo-R presents a consensus β-Trcp binding site in its intracellular domain. This sequence contains the canonical DSG motif followed by a hydrophobic residue that mediates β-Trcp binding. Typically, a phosphorylable serine residue should occur 2 or 3 amino acids after the glycine residue. In the Epo-R sequence, a threonine residue is present at this position. Several β-Trcp binding sites have been recently characterized and published results suggest that the presence of negatively charged residues rather than strict amino acid requirements constitute a β-Trcp binding motif. Indeed, β-Trcp recognizes a TSGCSS motif in the Per-1 protein,46 a DDGFLD motif in Cdc25A phosphatase,47 and clusters of serine residues in cubitus interruptus transcription factor.48 Thus, we can suppose that either the threonine residue after phosphorylation and/or the aspartic acid residue that is also conserved in zebrafish Epo-R (see Figure 1A) could contribute to the β-Trcp binding site. It is also likely that the SSG motif present in Xenopus Epo-R could be recognized by β-Trcp after phosphorylation of both serine residues. The high conservation of the β-Trcp motif among species strongly suggests that it could play an important role in Epo-R signaling.

Using AG490, we showed that Jak2 Tyr kinase activity is important for the interaction between Epo-R and β-Trcp. It is very likely that blocking Jak2 inhibits a downstream serine/threonine kinase involved in the phosphorylation of the β-Trcp binding motif. Further studies will be required to identify this serine/threonine kinase. It is noticeable that the protein kinases responsible for the phosphorylation of the β-Trcp binding motif in Prl-R and IFNAR-1 have not been identified to date.

Substrates of the SCF β-Trcp E3 ligases are preferentially ubiquitinated on lysines that are located proximal to the binding motif. Usually lysine residues located between 9 and 13 amino acids upstream from the DSG are efficiently ubiquitinated.20 The cytoplasmic tail of Epo-R contains 5 lysine residues and the last one, lysine 453, is located 9 amino acids from the DSG and is a potential ubiquitin acceptor site. Interestingly, Kumar et al showed that the mutation of 3 lysine residues drastically abolished IFNAR1 proteolysis and reduced IFNAR1 ubiquitination, but that ubiquitination can still be detected, demonstrating that alternative ubiquitine acceptor sites can be used when the major ones are mutated.49 The same observation has been reported concerning the EGF-R in which mutation of 6 lysine residues is necessary to strongly lower but not eliminate ligand-induced ubiquitination.44

Amplitude and duration of intracellular signaling are very important mechanisms that have to be tightly controlled. Loss of negative regulation plays an important role in receptor deregulation and can be linked to a large number of malignancies.50 Primary congenital and familial polycythemias are benign human pathologies often attributable to heterozygous mutations in the Epo-R gene. These nonsense mutations lead to the expression of Epo-Rs truncated by 59 to 110 amino acids that confer Epo hypersensitivity to erythroid progenitors.51,52 All these mutations remove the binding site for SHP-1 on Epo-R. It has been postulated that lack of SHP-1 recruitment results in prolonged Jak2 tyrosine phosphorylation and plays a major role in this pathology.7,53 However, all the mutations described in these families also remove the binding site for β-Trcp. Because our results show that a mutation that destroys the β-Trcp binding site also confers Epo hypersensitivity to transfected cells, we can wonder if the lack of β-Trcp binding site could contribute to the pathogenesis of familial polycythemia. Our results can also explain a previous observation made by D'Andrea et al, who have shown that deletion of the last 40 amino acids of Epo-R resulted in hypersensitivity for Epo of BaF3 cells expressing such a truncated Epo-R.54 This Epo-R mutation did not modify the SHP-1 binding site but affected the β-Trcp binding site because the second part of the destruction motif was removed. At that time, D'Andrea et al proposed the existence of a negative regulatory domain in the carboxyterminus of Epo-R. Our data suggest that β-Trcp is probably responsible for this negative regulatory effect. Further studies are necessary to investigate the relative importance played by SHP-1 and β-Trcp in the control of the duration of Epo-R signaling.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer (LNCC, laboratoire associé).

We thank Dr K. Strebel (NIH, Bethesda) and Dr S. Fuchs (University of Pennsylvania) for the generous gift of anti–β-Trcp antibodies.

Authorship

Contribution: L.M., B.D., and H.F. performed research and analyzed data; D.D. analyzed data and reviewed the manuscript; F.M.G reviewed the manuscript and contributed analytic tools; C.L. and P.M. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; and F.V. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Patrick Mayeux, Département d'hématologie, Institut Cochin, 27, rue du Faubourg Saint-Jacques F-75014 Paris, France; e-mail: mayeux@cochin.inserm.fr.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal