Abstract

Tetraspanin protein CD151 is abundant on endothelial cells. To determine whether CD151 affects angiogenesis, Cd151-null mice were prepared. Cd151-null mice showed no vascular defects during normal development or during neonatal oxygen-induced retinopathy. However, Cd151-null mice showed impaired pathologic angiogenesis in other in vivo assays (Matrigel plug, corneal micropocket, tumor implantation) and in the ex vivo aortic ring assay. Cd151-null mouse lung endothelial cells (MLECs) showed normal adhesion and proliferation, but marked alterations in vitro, in assays relevant to angiogenesis (migration, spreading, invasion, Matrigel contraction, tube and cable formation, spheroid sprouting). Consistent with these functional impairments, and with the close, preferential association of CD151 with laminin-binding integrins, Cd151-null MLECs also showed selective signaling defects, particularly on laminin substrate. Adhesion-dependent activation of PKB/c-Akt, e-NOS, Rac, and Cdc42 was diminished, but Raf, ERK, p38 MAP kinase, FAK, and Src were unaltered. In Cd151-null MLECs, connections were disrupted between laminin-binding integrins and at least 5 other proteins. In conclusion, CD151 modulates molecular organization of laminin-binding integrins, thereby supporting secondary (ie, after cell adhesion) functions of endothelial cells, which are needed for some types of pathologic angiogenesis in vivo. Selective effects of CD151 on pathologic angiogenesis make it a potentially useful target for anticancer therapy.

Introduction

Angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels from preexisting vasculature, is crucial for many physiologic and pathologic situations.1-3 It involves coordinated endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation, with integrin-type adhesion receptors playing major roles.4-6 Although vitronectin-, fibronectin-, and collagen-binding integrins have been most extensively studied, laminin-binding integrins (α3β1, α6β1, α6β4) are also involved.7-11 For example, during the later stages of angiogenesis, α3β1 and α6β1 integrins may retard morphogenic and proliferative events, while promoting basement membrane assembly, pericyte association, and tube stabilization.7 By contrast, α6β4 may regulate the onset of pathologic angiogenesis in mature blood vessels.12

CD151, a tetraspanin protein family member,13 associates closely with laminin-binding integrins, thereby modulating α3β1-, α6β1-, and α6β4-dependent neurite outgrowth, cell migration, cell morphology, and adhesion strengthening. Mutation of CD151 in humans yielded kidney and skin disorders, but no obvious impairments in blood vessel formation or function were noted.14 Mice in which Cd151 was deleted were surprisingly normal, while showing only ex vivo deficiencies in platelet aggregation, keratinocyte migration, and T-cell proliferation.15,16 Again, there were no obvious blood vessel deficiencies. CD151 is present on many cell types, including endothelial cells, where it may either promote17 or inhibit18 in vitro formation of capillary-like cellular cables in Matrigel. Given the links between laminin-binding integrins and angiogenesis, and between CD151 and laminin-binding integrins, we hypothesized that CD151 might possibly support or suppress pathologic angiogenesis, even though it was apparently not needed for normal developmental angiogenesis. To test this hypothesis, we first generated Cd151-null mice. As seen elsewhere,15 our Cd151-null mice showed normal viability, fertility, laminin-binding integrin expression, tissue organization, and organ function, under normal physiologic conditions. Also, developmental angiogenesis appeared normal. With respect to in vivo angiogenesis assays, Cd151-null mice showed surprisingly selective defects. Whereas neovascularization was unaffected in an oxygen-induced retinopathy assay, it was markedly deficient in other in vivo assays (Matrigel plug, corneal micropocket, tumor implantation). Furthermore, Cd151-null endothelial cells showed marked in vitro alterations in cell spreading, motility, 3-dimensional morphology, and tissue remodeling assays, as well as selective signaling defects. Defects were particularly evident for cells plated on laminin substrate and were accompanied by changes in molecular organization of laminin-binding integrin protein complexes.

Materials and methods

CD151-null mice and cells

By targeted deletion, Cd151 was deleted from 129SvEv mice. The deletion starts from a site in the 5′ untranslated region, removes the first 4 Cd151-coding exons and part of the fifth (of 6), and includes the first 168 amino acids (of 253). Cd151 deletion was verified by Southern analysis of embryonic stem (ES) cells and reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis of embryo fibroblasts, as will be described in detail elsewhere. Cd151-null mice were backcrossed more than 7 generations into the C57BL/6J mouse strain, and genotyping of breeding pairs was confirmed by PCR. In all studies, Cd151-null mice, 7 to 12 weeks old and pathogen-free, were compared with littermates of the same age and sex. Animal studies were performed with approval from the relevant institutional committees. Mouse lung endothelial cells (MLECs) were isolated as described.19 Briefly, cells were selected from collagenase-digested lung tissue (using anti–mouse CD31–coated beads) and enriched (using anti–mouse ICAM-2) to more than 90% purity (positively stained for von Willebrand factor).

Aortic ring assay

Thoracic aortas were isolated from wild-type (WT) and Cd151-null mice under a dissecting microscope, cut into 1-mm sections, and embedded in 24-well Matrigel-coated plates. Medium containing 20% fetal bovine serum, 10 U/mL heparin, 50 μg/mL endothelial cell mitogen, and 20 ng/mL bFGF was added to each well of gelled Matrigel. Microvessel-like properties of sprouting structures was confirmed by their incorporation of acetylated low-density lipoprotein labeled with 1,1′-diocctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine percholate (Dil-Ac-LDL) as described.20

Matrigel plug assay

As described,21 8-week-old mice were given subcutaneous injections at the abdominal midline with 0.4 mL Matrigel supplemented with 400 ng bFGF. After 7 days, mice were killed and vessels penetrating into the Matrigel were visualized using anti-CD34 antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and quantified using Scion Image software. To test hemoglobin content, Matrigel plugs were excised, weighed, homogenized in Drabkin reagent (Sigma, St Louis, MO), and centrifuged, and then supernatants were measured at OD 540 nm, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Tumor transplantation into mice

Mice were injected subcutaneously with Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells (1 × 106 cells/mouse). Tumors were measured every 5 days using Vernier calipers and volume calculated (length × width2 × 0.52). After 15 days, tumors were collected and weighed. Tumor fragments were either frozen in OCT compound and then snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen or fixed in 10% formalin for histologic analysis.

Corneal angiogenesis assay

Corneal angiogenesis was assessed as described.22 Briefly, corneal micropockets were created, using a von Grafe knife, in both eyes of 6- to 8-week-old male mice. Micropellets containing 20 or 40 ng bFGF were implanted into each corneal pocket at 1 mm from the limbus. After 5 days, eyes were viewed under a dissecting microscope. The area of neovascularization was calculated using the formula 0.2 × π × vessel length × clock hours. After the mice were killed, corneas were dissected and fixed in acetone for 10 minutes (at 4°C), blocked, and stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD31 antibody (1:500; BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) as described.23

Proliferation, adhesion, flow cytometry, and immunoprecipitation

For MLECs seeded onto gelatin-coated 96-well tissue culture plates at 3000 cells/well, proliferation was assessed using methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT; Promega, Southampton, United Kingdom), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Static cell adhesion was quantified as described,24 on substrates coated onto plastic for 12 hours at 10 μg/mL (fibronectin [FN] collagen I [Col]; laminin-1 [LM]), at 0.1% (gelatin) or diluted 1:30 from stock solution(Matrigel [Mat]; BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA).

Flow cytometry was performed using monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to mouse CD9 (KMC8), CD81 (Eat1), and integrins α2 (HMa2), α4 (R1-2), α5 (5H10/27), α6 (GoH3), αV (H9.2B8), β1 (KMI-6), and β4 (346-11A), all from BD Biosciences. Prior to immunoprecipitation, MLECs were washed twice in PBS, serum-starved for 3 hours, labeled for 2 hours in medium containing 0.2 to 0.3 mCi/mL (7.4-11.1 MBq) [3H]-palmitic acid with 5% dialyzed FCS, then lysed in 1% Brij-96 for 1 hour at 4°C. Immunoprecipitation and [3H]-palmitate detection was as described,25 using anti-CD9 mAb KMC8, and mixed anti-β1 antibodies (HMβ1, 9EG7).

Cell spreading and motility assays

To assess cell spreading,18 MLECs were suspended in DMEM containing 2% FCS and seeded onto plates coated with fibronectin (10 μg/mL), gelatin (0.1%), or Matrigel (1:30 dilution). We counted spread cells and nonspread cells in 3 high-power fields 30 minutes after plating (in duplicate wells for each group). Cells defined as spread showed a flattened morphology and were no longer phase-bright by light microscopy.

Chemotactic migration was performed26 using polycarbonate filter wells (Transwell, 8-μm pores; Costar, Corning, NY) coated with fibronectin, gelatin, or Matrigel (as described). MLECs were plated (7 × 104 cells in 200 μL DMEM containing 5% FCS) in the upper chamber. The bottom chamber contained 5% FCS and 20 ng/mL bFGF as chemoattractants in 600 μL DMEM. After 7 hours at 37°C, filters were stained with Diff-Quick (Merz-Dade, Dudingen, Switzerland) and migrated cells, in duplicate wells, were counted each in 4 randomly chosen microscopic fields using a × 20 objective.

For Matrigel invasion assays, MLECs (1 × 105) were resuspended in DMEM supplemented with 5% FCS, in the upper compartment of Matrigel invasion chambers (Becton Dickinson, Bedford, MA). The lower compartment contained DMEM supplemented with 5% FCS and bFGF (20 ng/mL) chemoattractants. After 16 hours at 37°C, filters were stained with Diff-Quick and invaded cells, in triplicate wells, were counted each in 4 randomly chosen microscopic fields using a × 20 objective.

Random migration was assessed using acid-washed glass coverslips spanning a 12-mm hole drilled in a 60-mm dish, which had been coated overnight with Matrigel and blocked with 5 mg/mL cell culture-grade bovine serum albumin (ICN Pharmaceuticals, Santa Ana, CA). For image acquisition, MLECs were detached and plated at 105 cells/dish in medium containing 5% FCS. Images were acquired every minute for 30 minutes using a Zeiss Axiovert 135 microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Using Scion Image freehand tools, x and y centers were calculated, and the distance moved was determined.

Three-dimensional assays

To assess cable formation,18 endothelial cells (1 × 105 in 200 μL DMEM plus 5% FCS) were placed on Matrigel, in 48-well plates (in duplicate for each group), then cables were quantified from high-power fields (× 200) and at least 3 random fields were photographed. For Matrigel contraction assays,27 DMEM containing melted 1% agarose (250 μL) was added to 24 well-plates. After cooling, 50 μL Matrigel was added and gelled at 37°C for 30 minutes, then MLECs (2 × 105/well in DMEM with 5% FCS) were added. After 18 hours, images were digitally recorded and Matrigel diameter was measured.

To assess tube formation in collagen,28 10 × DMEM (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), neutralizing buffer (NaHCO3) and collagen gel (rat tail collagen I; BD Biosciences) were mixed 1:1:8 on ice, added to a 48-well plate (100 μL/well), and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. Then, MLECs were seeded at 6 × 104/well in the same wells, incubated for 5 hours at 37°C, medium was removed, and cells were washed with PBS. Collagen gel mixture prepared as described was added again, this time on top of the cells. After 30 minutes, 300 μL complete media containing PMA (50 nM), VEGF (20 ng/mL, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and bFGF (20 ng/mL, R&D Systems) was added and plates were incubated in 5% CO2 at 37°C. Tube formation was observed after 48 hours.

To measure spheroid sprouting, MLECs (1 × 103) were suspended in medium containing 0.25% (wt/vol) carboxymethylcellulose, seeded in nonadherent round-bottom 96-well plates, and cultured at 37°C for 24 hours. Spheroids were collected by centrifugation at 500g for 3 minutes. A collagen stock solution, prepared as above, was mixed 1:1 with DMEM containing 20% FCS and 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose. This spheroid-containing gel was transferred into 24-well plates and polymerized for 30 minutes. Then, 400 μL complete medium containing bFGF (20 ng/mL), PMA (10 nM), and VEGF (20 ng/mL) was overlaid on the collagen gel. After 24 and 48 hours, cumulative lengths of all capillary-like sprouts from individual spheroids were measured using Scion Image software. For each data point, at least 8 randomly selected spheroids were analyzed. All statistical analyses used 2-tailed Student t test. Results showing P values less than .05 were regarded as significant. For images acquired using an Axiovert 135 inverted microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY), we used objective lenses of 5×/0.15 (Figures 1A and 5A,C) and 10×/0.25 (Figures 1B and 5D). Photos were acquired using Scion Image software and an RT Monochrome SPOT camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI). Fluorescent images in Figures 2B and 3 were obtained using a Nikon Eclipse TE300 inverted microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) equipped with an objective lens of 10×/0.3 and an RT SE SPOT camera (Diagnostic Instruments), and were acquired with Scion Image software. Images in Figures 2A and 5B were acquired using a digital camera. All photos were processed (cropped, labeled, organized) for publication using Canvas 9.0 (ACD Systems, Miami, FL).

Signaling assays

Serum-starved MLECs plated on diluted Matrigel were lysed in buffer containing 1% NP-40. Equal amounts of proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), transferred to nitrocellulose, then immunoblotted. Anti–phospho-Akt (Ser473), anti-Akt, anti–phospho-Raf (Ser259), anti–c-Raf, anti–phospho-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182), anti-p38, anti–phospho-Src (Thy416), anti–phospho-FAK (Tyr925), anti–phospho-eNOS (Ser1177), anti–phospho-Erk (Thr202/Tyr204), all were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA), anti-eNOS was from BD Biosciences, and anti–c-Src was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). To measure Rac1 activity (using Rac1 Activation Assay Kit, Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), cell supernatants were incubated with glutathione S-transferase (GST)–PBD agarose beads (1 hour, 4°C), washed, then bound material and total cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-Rac antibody (Upstate Biotechnology) and anti-Cdc42 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Results

CD151 deletion selectively impairs pathologic angiogenesis

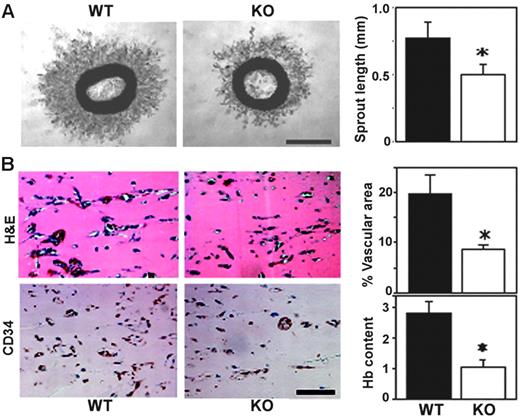

Mouse “aortic ring” explants embedded in Matrigel give rise to capillary-like structures.29 Aortic rings from Cd151-null mice showed impaired microvascular sprouting (representative photographs are shown in Figure 1A). Mean length of newly sprouted vessels was reduced by about 35% after 4 days in this ex vivo assay (Figure 1A). To assess angiogenic capacity in vivo, we used an assay in which implanted Matrigel plugs are invaded by host endothelial cells to form a capillary network.21 Matrigel plugs excised from Cd151-null mice, 7 days after implantation, showed diminished vascularization by 2 different staining methods (Figure 1B left panels), and vascular area and hemoglobin content were both decreased by about 60% (right panels).

CD151-null mice show diminished angiogenesis, ex vivo and in vivo. (A) Thoracic aortic rings were embedded in Matrigel and incubated for 4 days. Shown are phase-contrast images of branching vessel-like structures in WT and CD151-null explants. Lengths of vessel-like structures were quantitated (n = 6; *P < .005). (B) After implantation for 7 days, sections of Matrigel plugs were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and for endothelial marker CD34. Percentage of vascular area stained with CD34 was calculated, in 5 fields, using Scion Image software. Results are shown as the mean ± SEM. (*P < .01). Hemoglobin content was also determined (n = 5; *P < .05). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results. Scale bars represent 1 mm (A) and 100 μm (B). Bar graphs in panels A-B, and in every other figure, show mean ± SEM.

CD151-null mice show diminished angiogenesis, ex vivo and in vivo. (A) Thoracic aortic rings were embedded in Matrigel and incubated for 4 days. Shown are phase-contrast images of branching vessel-like structures in WT and CD151-null explants. Lengths of vessel-like structures were quantitated (n = 6; *P < .005). (B) After implantation for 7 days, sections of Matrigel plugs were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and for endothelial marker CD34. Percentage of vascular area stained with CD34 was calculated, in 5 fields, using Scion Image software. Results are shown as the mean ± SEM. (*P < .01). Hemoglobin content was also determined (n = 5; *P < .05). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results. Scale bars represent 1 mm (A) and 100 μm (B). Bar graphs in panels A-B, and in every other figure, show mean ± SEM.

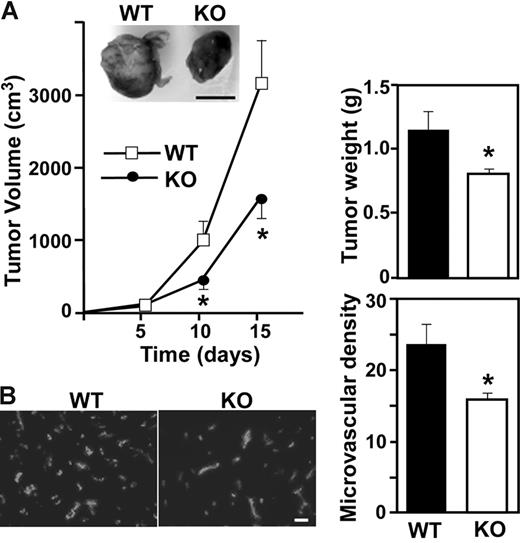

Alterations in aortic ring outgrowth or Matrigel plug infiltration is typically accompanied by altered tumor angiogenesis.21,30,31 Hence, we implanted LLC cells into our mice. Representative photos (day 15) show smaller solid tumors in CD151-null mice compared to WT mice, with marked reduction in tumor volume and weight (Figure 2A). Furthermore, tumors from CD151-null mice showed significantly decreased microvessel density, as assessed by anti-CD31 staining (Figure 2B). Hence, CD151 may play a key role during tumor angiogenesis, in host mice, and possibly also in humans. In this regard, CD151 is present on both human tumor cells and tumor vasculature. CD151 showed especially high levels on colon cancer vessels and some increase also on tumor vessels in lung, breast, and prostate cancer compared to normal vessels in the same organs (Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Figures link at the top of the online article).

Impaired tumor angiogenesis in Cd151-null mice. (A) LLC tumor growth was assessed in 10 age- and sex-matched WT and knockout (KO) mice. Data are representative of 5 independent experiments. From tumors such as shown in the photo, tumor volume and tumor weight were calculated (n = 10; *P < .05). (B) Cryosections of LLC tumors were stained for endothelial marker CD31 and the number of CD31+ blood vessels was counted (*P < .01). Scale bars represent 1 cm (A) and 100 μm (B).

Impaired tumor angiogenesis in Cd151-null mice. (A) LLC tumor growth was assessed in 10 age- and sex-matched WT and knockout (KO) mice. Data are representative of 5 independent experiments. From tumors such as shown in the photo, tumor volume and tumor weight were calculated (n = 10; *P < .05). (B) Cryosections of LLC tumors were stained for endothelial marker CD31 and the number of CD31+ blood vessels was counted (*P < .01). Scale bars represent 1 cm (A) and 100 μm (B).

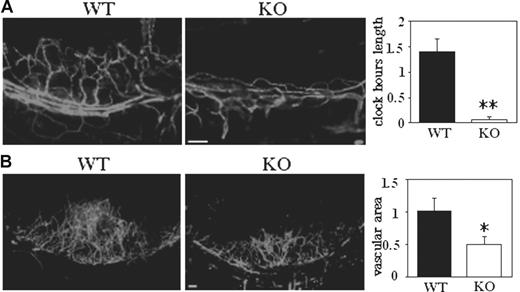

To gain mechanistic insight into the role of CD151 during angiogenesis in vivo, we used a corneal micropocket assay.22,23 After 5 days of exposure to an implanted pellet containing a low dose of bFGF (20 ng), corneas of WT mice showed limbic vessel looping, dilation, and sprouting (Figure 3A). In sharp contrast, corneal vessels from Cd151-null mice showed minimal bFGF-stimulated sprouting, as evidenced by a greater than 95% reduction in clock-hour length (Figure 3A). At a higher bFGF dose (40 ng), neovascularization in CD151-deficient corneas was again markedly diminished (Figure 3B), resulting in reduced vascular area.

Corneal angiogenesis is deficient in Cd151-null mice. (A) Five days after implantation of pellets containing 20 ng bFGF, vessels were stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD31. Clock-hour length of sprouting vessels was quantitated (**P < .005). (B) Corneal pellets contained 40 ng bFGF. After 5 days, vessels were stained with anti-CD31, and vascular area was quantitated (*P < .05). Scale bars represent 100 μm in panels A-B.

Corneal angiogenesis is deficient in Cd151-null mice. (A) Five days after implantation of pellets containing 20 ng bFGF, vessels were stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD31. Clock-hour length of sprouting vessels was quantitated (**P < .005). (B) Corneal pellets contained 40 ng bFGF. After 5 days, vessels were stained with anti-CD31, and vascular area was quantitated (*P < .05). Scale bars represent 100 μm in panels A-B.

Cd151-null mice developed normally in different mouse genetic backgrounds (129Sv and C57BL/6) without obvious vascular deficiencies, in any tissues or organs analyzed, including skin, lungs, kidneys, liver, and heart (not shown). For example, in retina, in which vascularization is readily visualized, WT and Cd151-null mice showed no difference in the development of superficial radial and collateral vessels (Figure S2). Furthermore, Cd151-null mice showed no difference in oxygen-induced retinal neovascularization, in multiple experiments, as seen either by lectin staining or by histologic examination (Figure S3). These results indicate that CD151 is not needed for normal vascular development but supports pathologic angiogenesis in some, but not all, circumstances.

CD151 minimally affects endothelial cell proliferation, adhesion, and integrin expression

To address mechanisms whereby CD151 might affect pathologic angiogenesis, we isolated MLECs from WT and CD151-null mice. MLECs, enriched to more than 90% purity, showed minimal differences in proliferation (Figure S4A) or in static cell adhesion to 5 different ECM substrates, including purified laminin-1 and laminin-rich Matrigel (Figure S4B). Apoptosis, assessed by a DNA/histone complex assay, was unaltered in cells plated on either 2-dimensional Matrigel or gelatin (not shown). Also, cells were plated within 3-dimensional collagen or Matrigel for 2 days, with or without 10% serum, and then thin sections were analyzed by TUNEL staining. In the presence of serum, 10% to 14% of cells showed apoptosis. In the absence of serum apoptosis was elevated (34%-38% in collagen; 21%-24% in Matrigel). In no condition was there a significant difference between Cd151 WT and null MLECs. Furthermore, WT and knockout MLECs expressed other tetraspanins (CD9 and CD81) and integrins (α2, α4, α5, α6, αV, β1, β4) at similar levels on the cell surface, except for a possible slight increase in α6 in Cd151-null cells (Figure S4C, and not shown).

CD151 affects MLEC spreading, chemotaxis, invasion, and intrinsic migration

Although absence of CD151 did not affect parameters measured in Figure S4, it did alter several cell functions (spreading, migration, invasion, chemotaxis) that are relevant to angiogenesis initiation and progression.3,7 First, the number of Cd151-null cells spread on Matrigel (for 30 minutes) was decreased by about 50%, whereas spreading on fibronectin and gelatin was decreased to a much lesser extent (Figure 4A). Second, Transwell migration of Cd151-null MLECs, toward bFGF chemoattractant, was significantly reduced when wells were coated with Matrigel or gelatin, but not fibronectin (Figure 4B). Third, invasion through Matrigel was more than 50% diminished for CD151 knockout MLECs compared to WT cells (Figure 4C).

CD151 affects endothelial cell spreading, chemotaxis, invasion, and random migration. (A) To assess spreading, MLECs were seeded onto plates coated with fibronectin, gelatin, or Matrigel. After 30 minutes, spread cells were counted in 3 high-power fields in duplicate wells (*P < .01). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results. (B) For chemotactic migration, MLECs (7 × 104 cells in 200 μL DMEM; 5% FCS) were plated in upper Transwell chambers, coated with fibronectin, gelatin, or Matrigel (thin layer). Bottom chambers contained 600 μL DMEM, 5% FCS, and 20 ng/mL bFGF. Cells migrating through the filter were counted (*P < .05; **P < .01). (C) To assess invasion, cells were counted after migrating for 6 hours through a Matrigel-coated Transwell (n = 3; *P < .005). (Di) To measure random migration, cells were plated on coverslips coated with Matrigel or gelatin. (ii) Cell movements were recorded by time-lapse video microscopy every minute for 30 minutes and quantified using Scion Image tools (n = 12). Top panels show randomly selected individual migration tracks copied and combined (bars = 100 μm). Bottom panels show “T” and “D/T” where T is total distance migrated and D is distance between starting and ending point (*P < .05). High D/T ratios (approaching 1.0) indicate directional persistence.32 Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results.

CD151 affects endothelial cell spreading, chemotaxis, invasion, and random migration. (A) To assess spreading, MLECs were seeded onto plates coated with fibronectin, gelatin, or Matrigel. After 30 minutes, spread cells were counted in 3 high-power fields in duplicate wells (*P < .01). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results. (B) For chemotactic migration, MLECs (7 × 104 cells in 200 μL DMEM; 5% FCS) were plated in upper Transwell chambers, coated with fibronectin, gelatin, or Matrigel (thin layer). Bottom chambers contained 600 μL DMEM, 5% FCS, and 20 ng/mL bFGF. Cells migrating through the filter were counted (*P < .05; **P < .01). (C) To assess invasion, cells were counted after migrating for 6 hours through a Matrigel-coated Transwell (n = 3; *P < .005). (Di) To measure random migration, cells were plated on coverslips coated with Matrigel or gelatin. (ii) Cell movements were recorded by time-lapse video microscopy every minute for 30 minutes and quantified using Scion Image tools (n = 12). Top panels show randomly selected individual migration tracks copied and combined (bars = 100 μm). Bottom panels show “T” and “D/T” where T is total distance migrated and D is distance between starting and ending point (*P < .05). High D/T ratios (approaching 1.0) indicate directional persistence.32 Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results.

Whereas cell spreading, chemotaxis, and invasion were decreased for Cd151-null cells, intrinsic 2-dimensional migration was increased, most notably for cells plated on Matrigel, and to a lesser extent on gelatin (Figure 4D). In addition, Cd151-null cells displayed increased directional persistence, as evidenced by a higher D/T ratio, where D is the distance between starting and ending point, and T is the total distance traveled.32

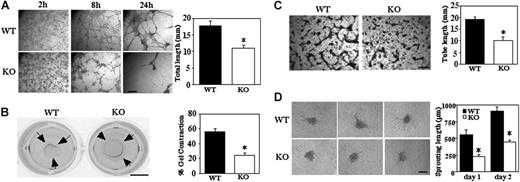

CD151-null MLECs show attenuated 3-dimensional functions in vitro

Formation of a network of cellular cables on Matrigel is a property of endothelial cells that models formation of new vasculature.33 Cellular cables formed by Cd151-null MLECs were markedly diminished (Figure 5A), as seen in representative photos (after 8 and 24 hours), and by quantitation (38% decrease after 8 hours). Another assay involving laminin-binding integrins (and therefore possibly CD151) is the Matrigel contraction assay, which assesses mechanical forces relevant to angiogenesis.27 MLECs from WT mice contracted Matrigel as it detached from the underlying agarose support, whereas contraction by Cd151-null cells was about 60% impaired (Figure 5B). As expected, Matrigel contraction was completely inhibited by anti-α6 antibody (GoH3, 20 μg/mL; not shown).

Impaired 3-dimensional functions on Matrigel and collagen. (A) MLECs were seeded on Matrigel and photographed at indicated times (bar = 1 mm). Total length of cellular cables was quantitated after 24 hours (*P < .001). (B) Representative photographs of Matrigel contraction data are shown for WT and Cd151-null MLECs (bar = 5 mm). Percent contraction (after 18 hours) is the average gel diameter/well diameter × 100 (*P < .05). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results. (C) MLECs were incubated within collagen gel for 48 hours, then fixed, stained with toluidine blue, and photographed (bar = 1 mm). Total tube length is quantitated (n = 2; *P < .05). (D) Representative images are shown of capillary-like structures sprouting from MLEC spheroids after 48 hours (bar = 100 μm). Total sprouting length is quantitated (*P < .005). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results. Note that the initial size of spheroids, when first transferred to collagen gel, was similar for WT and Cd151-null cells (136 ± 12 μm and 145 ± 13 μm, respectively).

Impaired 3-dimensional functions on Matrigel and collagen. (A) MLECs were seeded on Matrigel and photographed at indicated times (bar = 1 mm). Total length of cellular cables was quantitated after 24 hours (*P < .001). (B) Representative photographs of Matrigel contraction data are shown for WT and Cd151-null MLECs (bar = 5 mm). Percent contraction (after 18 hours) is the average gel diameter/well diameter × 100 (*P < .05). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results. (C) MLECs were incubated within collagen gel for 48 hours, then fixed, stained with toluidine blue, and photographed (bar = 1 mm). Total tube length is quantitated (n = 2; *P < .05). (D) Representative images are shown of capillary-like structures sprouting from MLEC spheroids after 48 hours (bar = 100 μm). Total sprouting length is quantitated (*P < .005). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results. Note that the initial size of spheroids, when first transferred to collagen gel, was similar for WT and Cd151-null cells (136 ± 12 μm and 145 ± 13 μm, respectively).

Although the Matrigel cable assay is instructive (Figure 5A), cells form few if any lumens. However, endothelial cells grown within type I collagen gels form branching networks that do contain lumens.28 In this in vitro model for angiogenesis, Cd151-null MLECs again were deficient because tube formation was decreased by approximately 48% (Figure 5C).

Sprouting from preexisting blood vessels can be modeled in a 3-dimensional assay, in which capillary-like structures, containing lumens, sprout from spheroids embedded in collagen gel together with growth factors.34 To evaluate the role CD151, spheroids from WT and Cd151-null MLECs were grown in collagen gel containing bFGF and VEGF. After 24 and 48 hours, the cumulative length of all capillary-like sprouts from Cd151-null spheroids was significantly shorter than that of Cd151 WT spheroids (Figure 5D). Furthermore, the mean number of sprouts from each spheroid, after 2 days, was also significantly decreased (4.1 ± 2.1 versus 10.5 ± 3.0; P < .001).

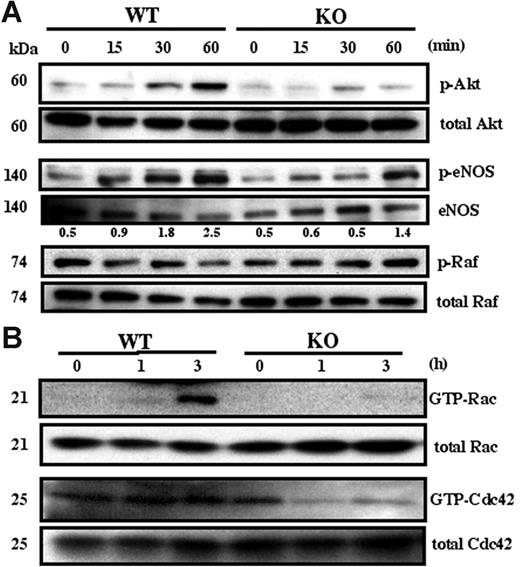

Cd151-null MLECs show altered signaling

Many signaling pathways (eg, involving Akt, eNOS, Rac, Cdc42, ERK, Raf, p38 MAPK, FAK, Src) contribute to endothelial cell angiogenesis.35-37 Here we determined which are affected by absence of CD151. Phosphorylation of Akt was markedly attenuated in Cd151-null MLECs compared to WT MLECs, when plated for 30 or 60 minutes on Matrigel (Figure 6A). No difference was seen for cells plated on gelatin (not shown). Up-regulation of phosphorylated eNOS was also somewhat attenuated in Cd151-null MLECs (Figure 6A), consistent with endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) being activated in an Akt-dependent manner.36 By contrast, phosphorylation of components in, or upstream of, the MAPK pathway, such as Raf (Figure 6A), p38 MAPK, ERK, Src, and FAK (not shown), were not affected by the absence of CD151. Rac and Cdc42 are molecules frequently linked to endothelial cell spreading, migration, and 3-dimensional morphology.37 After 3 hours on Matrigel (when cable formation begins to become obvious), Cd151-null MLECs, compared to WT MLECs, showed markedly diminished activation of Rac and Cdc42 (Figure 6B).

Adhesion-dependent MLEC signaling. (A) Serum-starved MLECs were detached, suspended for 1 hour, and plated on Matrigel-coated plates for the indicated times. Equal amounts of lysate were probed with antibodies to activated Akt (p-Akt), activated Raf (p-Raf), and activated eNOS (p-eNOS). Numbers represent p-eNOS (from densitometry) normalized for eNOS amounts. (B) Serum-starved MLECs were plated on Matrigel and analyzed for Rac and Cdc42 activation at the indicated times. Western blots in this figure are each representative of 3 experiments with different cell preparations.

Adhesion-dependent MLEC signaling. (A) Serum-starved MLECs were detached, suspended for 1 hour, and plated on Matrigel-coated plates for the indicated times. Equal amounts of lysate were probed with antibodies to activated Akt (p-Akt), activated Raf (p-Raf), and activated eNOS (p-eNOS). Numbers represent p-eNOS (from densitometry) normalized for eNOS amounts. (B) Serum-starved MLECs were plated on Matrigel and analyzed for Rac and Cdc42 activation at the indicated times. Western blots in this figure are each representative of 3 experiments with different cell preparations.

CD151 deletion alters laminin-binding integrin complexes

CD151 may link laminin-binding integrins to multiple other proteins, within tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (TEMs), to affect integrin-dependent functions.13,25,38 Laminin-binding integrins, nearly all tetraspanins, and various tetraspanin-associated proteins readily incorporate [3H]-palmitate. Thus, metabolic labeling with [3H]-palmitate is a useful and selective method for analyzing integrin-tetraspanin complexes. As indicated (Figure 7A lanes 1 and 2), anti-β1 antibodies immunoprecipitated similar levels of [3H]-palmitate–labeled laminin-binding integrins (α3β1, α6β1) from WT and null MLECs. As expected, Cd151-null cells yielded no CD151 (Figure 7A lane 2). In parallel, amounts of 5 other proteins (labeled d1-d5) were markedly diminished when CD151 was absent (lane 2). The decrease in proteins d3 (CD9) and d4 (CD81) was confirmed by immunoblotting with anti-CD9 and anti-CD81 antibodies (not shown). Identities of d1, d2, and d5 are unknown. In control experiments, amounts of palmitoylated proteins associated with CD9 (Figure 7A lanes 3 and 4) were relatively unchanged by the absence of CD151, except, of course, for CD151 itself. In conclusion, structural links between specific laminin-binding integrins (α3β1, α6β1) and other proteins (eg, d1-d5) are disrupted when CD151 is absent (shown schematically in Figure 7B).

CD151 causes substantial modification of integrin complexes. (A) MLECs were labeled with [3H]-palmitate and lysed in 1% Briji-96 buffer. Immunoprecipitations were carried out using mAbs HMβ1-1 + 9EG7 (for β1 integrins) and mAb KMC8 (for CD9). Several integrin-associated proteins, including CD151 itself, are substantially decreased in amount when CD151 is absent (lane 2). These are marked with white arrows and (except for CD151 itself) are labeled as d1-d5. Proteins that are relatively unchanged are marked with black arrows. Note that the integrin β1 subunit does not appear because it does not undergo palmitoylation. Immunoprecipitation of mouse α3 complexes yielded very similar results—proteins similar in size to d1-d5 were again mostly lost from α3β1 complexes when CD151 was absent (not shown). (B) The schematic diagram emphasizes that CD151 plays a key role in linking α3β1 and α6β1 integrins to several other unknown and known proteins, including other tetraspanins CD9 and CD81.

CD151 causes substantial modification of integrin complexes. (A) MLECs were labeled with [3H]-palmitate and lysed in 1% Briji-96 buffer. Immunoprecipitations were carried out using mAbs HMβ1-1 + 9EG7 (for β1 integrins) and mAb KMC8 (for CD9). Several integrin-associated proteins, including CD151 itself, are substantially decreased in amount when CD151 is absent (lane 2). These are marked with white arrows and (except for CD151 itself) are labeled as d1-d5. Proteins that are relatively unchanged are marked with black arrows. Note that the integrin β1 subunit does not appear because it does not undergo palmitoylation. Immunoprecipitation of mouse α3 complexes yielded very similar results—proteins similar in size to d1-d5 were again mostly lost from α3β1 complexes when CD151 was absent (not shown). (B) The schematic diagram emphasizes that CD151 plays a key role in linking α3β1 and α6β1 integrins to several other unknown and known proteins, including other tetraspanins CD9 and CD81.

Discussion

Although CD151 is abundant on endothelial cells,39,40 anti-CD151 antibodies showed conflicting or marginal functional effects in vitro.17,18,40 Furthermore, disruption of the CD151 gene in humans14 and in mice15 caused no changes in normal physiology suggestive of vascular deficiencies. Indeed, our Cd151-null mice developed without overt vascular defects in any normal tissues or organs analyzed, including the retina, in which vessels are readily visualized. Nonetheless, we now provide strong evidence for CD151 playing a critical role during angiogenesis under selective pathologic conditions in vivo (Matrigel plug, tumor implantation, and corneal micropocket assays) and ex vivo (aortic ring sprouting assay). At present we do not understand why CD151 is apparently not needed during normal vascular development. We speculate that other tetraspanins, such as TSPAN11 (which shows the most sequence homology), could compensate for the absence of CD151 under normal conditions, but not in selected pathologic conditions.

With few exceptions, genetic alterations that affect Matrigel plug invasion, tumor angiogenesis, or corneal angiogenesis result in parallel effects on oxygen-induced retinal angiogenesis.12,41,42 How then do we explain the absence of Cd151 gene deletion effects in the oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) model? Retinal vascularization may be uniquely dependent on a preexisting astrocytic template.43 Thus, compared to the other angiogenesis models, endothelial cells in the OIR model may be less dependent on CD151-mediated adhesion strengthening on a laminin-basement membrane.

Tetraspanin Cd151 supports pathologic angiogenesis, most likely by modulating essential endothelial cell functions. Indeed, MLECs from Cd151-null mice showed deficiencies in several in vitro assays, highly relevant to angiogenesis. These include impairments in cell spreading, invasion, chemotactic migration, signaling, cable formation in Matrigel, Matrigel contraction, tube formation in collagen, and spheroid sprouting in collagen. It remains to be seen whether CD151 on nonendothelial cell types might contribute to pathologic angiogenesis. For example, tumor angiogenesis can be influenced by platelets,44 and CD151 contributes to platelet aggregation, spreading, and clot retraction.16 Also, endothelial interacting cells, such as smooth muscle cells and pericytes, play a role during angiogenesis.45 Indeed, CD151 is present on pericytes and vascular smooth muscle cells in normal39,46 and tumor (not shown) tissue, where it could possibly affect angiogenesis indirectly.

CD151 associates directly with laminin-binding integrins (α3β1, α6β1, α7β1, α6β4) on endothelial cells and other cell types, thereby modulating integrin-dependent spreading, motility, morphology, adhesion strengthening, and signaling.13,38,40,46,47 A genetic defect in human CD151 results in skin and kidney abnormalities14 that are less dramatic, but consistent with those occurring when integrin α3, α6, and β4 subunits are mutated or absent.48-50 In this study, the functional consequences of CD151 being absent were most obvious when cells were plated on laminin or Matrigel (of which laminin-1 is a major component), rather than fibronectin, collagen, or gelatin. It was only in longer term assays carried out over 7 to 48 hours (Figures 4B and 5C-D) that we saw functional differences on gelatin and collagen. We suspect that, during these longer term assays, endothelial cell production of its own laminin matrix51,52 contributes to the functional effects that were observed on collagen and gelatin.

Compared to other integrins (eg, αVβ3, αVβ5, α5β1), which have received much attention for their roles in angiogenesis,4,6 less is known regarding contributions of laminin-binding integrins. Endothelial cells produce multiple isoforms of laminin, which could serve as ligands for integrins.11,53 Because CD151 associates with α3β1, α6β1, and α6β4 on MLECs and other types of endothelial cells, it has the potential to modulate functions of each of these integrins during in vivo angiogenesis. For example, CD151 could modulate α6β4 function during the onset of the invasive phase of pathologic angiogenesis,12 but might affect other laminin receptors (eg α3β1, α6β1) in support of endothelial cell differentiation and stabilization in the later stages of angiogenesis.7 However, some contributions of laminin-binding integrins to angiogenesis may be independent of CD151. For example, deletion of the β4 integrin-signaling domain had a pronounced effect on retinal neovascularization,12 whereas deletion of Cd151 had no effect (this report).

Cd151-null MLECs (this study) and Cd151-null platelets16 did not show reduced static cell adhesion, consistent with CD151 not affecting initial ligand binding by laminin-binding integrins. Nonetheless, Cd151-null endothelial cells showed reduced cell spreading, invasion, chemotactic migration, Matrigel contraction, Matrigel cable formation, tube formation in collagen, and spheroid sprouting. A common feature of each of these assays is that tensional forces play a critical role, and thus a deficit in adhesion strengthening, such as can be caused by the absence of CD151,24 would have a major impact. Importantly, these in vitro functional assays recapitulate the invasion, sprouting, migration, and lumen-forming steps that occur in vivo, during angiogenesis.3,7

Laminin-binding integrins can activate PI3K-Akt,54,55 Rac1,56-58 Cdc42,57,59 ERK,12,60 p38 MAPK,61 FAK,60 src,62 and Raf63 pathways. However, only a subset of these signaling molecules (Akt, Rac1, and Cdc42) showed markedly reduced laminin-dependent activation in Cd151-null MLECs. These selective signaling deficiencies could help to explain the contribution of CD151 to endothelial cell physiology. The PI3K-Akt pathway regulates multiple steps in angiogenesis including migration, invasion, capillary formation, and permeability.36,64,65 Of the 3 major isoforms of Akt, Akt1 is the one most prominent in endothelial cells. Akt1-null ECs showed impaired sprouting from aortic rings and a decrease in directed endothelial cell motility in vitro.64,66 Hence, reduced aortic ring sprouting, capillary formation, invasion, and chemotactic migration seen in Cd151-null MLECs may be due to impaired Akt signaling. Because deletion of CD151 was accompanied by parallel reductions in Akt signaling and angiogenesis, we can overlook, for the moment, the recent finding that Akt can have both positive and negative effects on angiogenesis in vivo.66 Akt also can activate eNOS, leading to critical changes in vasodilation, vascular permeability, and cell motility needed for angiogenesis.36,66 Indeed, diminished Akt activation was accompanied by partly decreased eNOS activation in CD151-null MLECs. Although Akt is also known to regulate endothelial cell survival and proliferation,36,66 these functions may be less important here, because the absence of CD151 did not affect survival or proliferation of MLECs. It remains to be seen which of the many downstream targets of Akt36,66 are most important during CD151-dependent signaling.

During angiogenesis, Rac activation plays a major role by promoting endothelial cell motility and morphogenesis, leading to lumen formation.7,35 Cd151-null MLECs showed a marked decrease in Rac1 activity, consistent with decreased angiogenesis in vivo, and decreased chemotactic migration, spreading, and invasion in vitro. Cdc42 affects angiogenesis by cooperating with Rac in the formation of vascular lumens.67 In this regard, Cd151-null MLECs showed reduced in vitro tube formation, accompanied by reduced Cdc42 signaling. Thus (as seen for Akt), CD151 effects on Rac and Cdc42 signaling may explain CD151 effects on angiogenesis. Whereas cell spreading and chemotactic motility functions were diminished in Cd151-null MLECs, total migration (ie, migration velocity) and directionally persistent migration (Figure 4D) were increased. Notably, diminished Rac1 activity has been linked to increased velocity and directional persistence for fibroblasts and epithelial cells.32 Apparently, increased movement that is directionally persistent (for individual cells), but uncoordinated, is not conducive to increased angiogenesis.

Signaling through ERK, p38 MAPK, FAK, src, and Raf may help to regulate endothelial cell proliferation during angiogenesis.35 Cd151 deletion did not cause alterations in those signaling pathways in MLECs, consistent with lack of an effect on endothelial cell proliferation. Furthermore, lack of an effect on ERK signaling may help to explain why CD151 does not affect ERK-dependent, α6β4-dependent functions such as oxygen-induced retinopathy.12 Also essential during angiogenesis is matrix remodeling by metalloproteinases (MMPs).7 Even though CD151 has been linked to MMP-2 production,68 there was no change in MMP-2 or MMP-9 production or activation in Cd151-null MLECs (Figure S5). It remains to be seen whether other relevant MMPs, such as MT1-MMP, are altered by Cd151 deletion. In conclusion, CD151 makes a substantial contribution to a subset of laminin-dependent signaling pathways, thereby supporting selectively those laminin-dependent functions of endothelial cells that are needed for pathologic angiogenesis.

We propose that CD151 affects signaling, and associated downstream functions, by providing a physical link between laminin-binding integrins and key molecules (as yet unidentified) that are upstream of Akt, Rac1, and Cdc42 on endothelial cells. Different laminin-binding integrins and multiple tetraspanins (CD9, CD151) were previously shown to reside in overlapping complexes, known as tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (TEMs47,69 ). Here we show that absence of CD151 disrupts these TEMs, leading to reduced association of α3β1 or α6β1 integrins with at least 5 other [3H]-palmitate–labeled proteins (including tetraspanins CD9 and CD81). Within the context of TEMs, CD151, CD9, and CD81 can recruit signaling molecules such as PI 4-kinase70 and conventional PKC isoforms71 into complexes with laminin-binding integrins. This may be relevant to angiogenesis because PI 4-kinase either directly (through PtdIns4P) or indirectly (through PtdIns(4,5)P2) can provide substrates for PI 3-kinase, thus enhancing PI 3-kinase–Akt signaling. In addition, recruitment of PKC could potentially influence PKC-dependent modulation of vascular permeability, endothelial cell sprouting, migration, and vessel formation.72-74

Studies regarding CD151 and tumor progression have so far focused on the promalignancy role of CD151 on tumor cells.75-77 For example, recent RNAi knockdown studies78,79 point to CD151 contributing to migration and spreading of tumor cell lines. Now we provide perhaps the first definitive evidence that CD151 can affect tumor growth in a different way—by contributing to tumor angiogenesis in the host animal. Hence, if appropriate anti-CD151 inhibitors can be designed, they potentially could deliver a double hit—on the tumor as well as on supporting host vessels. Normal vessels would presumably be spared because CD151 did not appear to be essential for vasculogenesis or angiogenesis in the developing or adult mouse.

Authorship

Contribution: Y.T. and M.E.H. designed the studies and wrote the manuscript; Y.T., A.R.K., C.E.B., L.E.B, B.D.H, and A.K. performed research; A.R.K. contributed vital new reagents; and Y.T., A.R.K., L.E.B., A.K., and M.E.H. analyzed data.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors have no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Martin E. Hemler, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 44 Binney St, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail: martin_hemler@dfci.harvard.edu.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

We thank F. W. Luscinskas and D. Lamont for assistance with endothelial cell isolation, Dr R. Bronson (Rodent Histopathology Core, Harvard Medical School) for assistance with mouse histopathology, Dr Tatiana Kolesnikova for assistance with video microscopy, and Dr Xiuwei Yang for technical advice regarding [3H]-palmitate labeling.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant CA42368 (M.E.H.).

![Figure 7. CD151 causes substantial modification of integrin complexes. (A) MLECs were labeled with [3H]-palmitate and lysed in 1% Briji-96 buffer. Immunoprecipitations were carried out using mAbs HMβ1-1 + 9EG7 (for β1 integrins) and mAb KMC8 (for CD9). Several integrin-associated proteins, including CD151 itself, are substantially decreased in amount when CD151 is absent (lane 2). These are marked with white arrows and (except for CD151 itself) are labeled as d1-d5. Proteins that are relatively unchanged are marked with black arrows. Note that the integrin β1 subunit does not appear because it does not undergo palmitoylation. Immunoprecipitation of mouse α3 complexes yielded very similar results—proteins similar in size to d1-d5 were again mostly lost from α3β1 complexes when CD151 was absent (not shown). (B) The schematic diagram emphasizes that CD151 plays a key role in linking α3β1 and α6β1 integrins to several other unknown and known proteins, including other tetraspanins CD9 and CD81.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/109/4/10.1182_blood-2006-08-041970/4/m_zh80040708010007.jpeg?Expires=1765884949&Signature=AWsK5bmKQWmC-EK3L3~1dXrtb4Tcv7khYyn4SjzpaF6dFKLCHmDEkhbD0OgBxvNVeRPOm1rGZ9duf-GOWCTKzm14AmsOiLo-3GItxCfLyD0Xev5fj6uwIbN8mpQrtUVPfVk2DIcHNJI9bTw1yaS4lmRZFsr~bDUTmBpZEcwUja84R3ZJCI01wxAlbdlut--GFQx8dmLjH9GUtQFNLK1IAV3XW2cEdb~c~6W-lRz1xg8NT3SFBaVyvdAq1Q03uQHetZZ-AyKqgVBagfOO-1nHJwkkD~fF9C5~l~EYF9cSmrPaDHaQyGXgr93nonYVJ0LXX3SAMQHSW2GMboTxcVJcCw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal