Abstract

Immunologic memory is associated with the activation and expansion of antigen-specific T cells, followed by clonal deletion and survival of a small number of memory T cells. This study establishes that effector and rested memory T cells can acquire major histocompatibility complex (MHC)/CD80 molecules (antigen presentasome [APS]) upon activation in vitro and after vaccination in vivo. We demonstrate for the first time that acquisition of APS by rested memory T cells is correlated with increased levels of apoptosis in vivo and up-regulation of caspase-3, bcl-x, bak, and bax in our in vitro studies. Moreover, our results demonstrate that memory T cells with acquired APS can indeed become cytotoxic T lymphocytes and kill other cells through perforin-mediated lysis. In addition, they retained the production of interferon γ and T-helper 2 (Th2) type cytokines. The acquisition of APS by memory T cells might be an important checkpoint leading to the clonal deletion of the majority of effector T cells, possibly allowing the surviving cells to become long-term memory cells by default.

Introduction

The size of the peripheral lymphocyte pool is tightly regulated and remains relatively constant in the absence of diseases. Expansion of the T-cell pool during an immune response is followed by a deletion phase in which most of the newly generated effector cells are eliminated, thereby restoring total T-cell numbers to normal levels.1–3 The mechanisms that are involved in the elimination of effector cells are not yet fully characterized.

It is hypothesized that the loss of contact with antigen might lead to the cessation of T-cell receptor (TCR) stimulation and a decrease in cytokine levels, which might lead to cell death.4–6 Also, it is suggested that these cells are intrinsically short lived and programmed to die by default pathways.5 Moreover, the duration of the time that effector cells are exposed to antigen could be an important factor in memory T-cell generation and maintenance. Results from a previous study demonstrated that overwhelming viral infection can lead to the total elimination of the responding T cells.7 This suggests that cells that have been exposed to antigen for long periods of time undergo cell death, whereas cells arriving at the end of response and therefore exposed to less antigen can become activated without undergoing death pathways. In previous studies by our group and others, we have demonstrated that naive CD4 T cells acquire CD80 and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules upon activation.8–10 This acquisition was shown to be directly related to both the strength of signal 1 and the level of signal 2 on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and mediated through CD28. Previous studies have demonstrated that blocking of CD80, CD28, or the TCR reduced this acquisition.8,10 It has been suggested that these molecules are absorbed in the form of membrane fragments during cell-to-cell contact and, furthermore, the capture of these molecules from target cells is a metabolically active process that requires adenosine triphosphate (ATP).11 Moreover, when naive T cells acquire CD80, these cells themselves can act as APCs.9 In a series of studies, we have demonstrated that these acquired MHC/costimulatory-molecule complexes, which we have termed antigen presentasomes (APSs), are capable of sustaining the transcriptional activation and proliferation of naive CD4 T cells.12 However, very little is known about the role of APS acquisition in the regulation of the memory T-cell population.

In the current study, we have begun to address this question by examining the role of APS acquisition by CD4 T cells in the homeostatic regulation of memory CD4 T cells. Using CD4 T cells from pigeon cytochrome c88-104 peptide TCR transgenic (PCC TCR-Tg) mice, we demonstrate that memory CD4 T cells can acquire a higher amount of APS through CD28 interaction compared with naive CD4 T cells that were activated for the first time and up-regulate cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) molecules. Moreover, APS acquisition by memory CD4 T cells leads to cell death through both apoptosis and fratricide. Apoptosis of these cells was associated with the activation of BAX, BAK, and caspases pathways. Furthermore, our in vivo studies for the first time demonstrate that CD4 T cells acquire APS in vivo and that the acquisition of APS by CD4 T cells in the presence of antigen leads to enhanced apoptosis of these effector cells. Based on these findings, we suggest that APS acquisition by memory cells may play an important role in the regulation of clonal expansion at the end of the primary response.

Materials and methods

Peptide

MHC class II-IEk–restricted pigeon cytochrome c88-104 peptide (PCC; KAERADLIAYLKQATAK) and MHC class II–IAd–restricted ovalbumin 323-339 peptide (OVA323-339; ISQAVHAAHAEINEAGR) were obtained from the American Peptide Company (Sunnyvale, CA).

Animals

PCC 5CC7 TCR transgenic mice (PCC TCR-Tg mice) were generated by Dr Barbara Fazekis de St Groth and colleagues (Seder et al13 ) in 1992 and carry a transgene that encodes a T-cell receptor that is specific for a pigeon cytochrome c peptide, amino acids 81-104, presented by the MHC class II molecule IEk. Balb/c mice, PCC TCR-Tg mice, and DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice were obtained from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY) and bred in the National Cancer Institute animal facility under pathogen-free conditions according to National Institutes of Health (NIH) Animal Care regulations. Double knockout Balb/c mice for CD80 and CD86 (B7DKO) were a generous gift from Dr Richard Hodes (NIH). All of the animal studies were approved by the NIH Animal Care and Use Committee prior to the experiments.

APCs

The fibroblast cell line DCEK, expressing high levels of MHC class II-IEk and low levels of CD80, and the fibroblast cell line P13.9, expressing high levels of MHC class II-IEk and high levels of CD80, were used as APCs. Cell lines were provided by Dr R. Germain (NIH).

Generation of memory CD4 T cells in culture and acquisition of CD80

Memory CD4 T cells were generated and rested in vitro as described previously.9 Rested memory CD4 T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. To generate CD4/CD80acq (CD4 T cells that have acquired CD80; 2 × 109), memory T cells were incubated with APCs and PCC for 24 hours to acquire CD80 and then separated from APCs, as described previously.9

Antibodies and flow cytometry

Cell suspensions were stained with directly conjugated monoclonal antibodies (mAbs; anti-CD4 CY; anti-CD69 [H1.2F3] FITC; anti-CD80 [16-10A1] FITC; anti-CD28 [37.51] PE; anti–CTLA-4 [UC10-4F10-11] PE or appropriate isotype control; BD Biosciences PharMingen, San Diego, CA). Samples were analyzed with a FACS CALIBUR (BD, Mountain View, CA).

CD4 T-cell assays with APCs

CD4 T cells (1 × 106) were incubated with APCs (1 × 105 cells) in 48-well plates, with or without PCC, at peptide concentrations and time points indicated in “Results.” As for CD28-blocking assay, memory CD4 T cells were pretreated with 20 μg/mL of purified anti-CD28 (37.51) or the appropriate isotype control antibody (both BD Biosciences PharMingen) on ice for 30 minutes. The treated memory CD4 T cells along with the blocking antibody were then incubated with APCs and 0.001 μg/mL PCC for 24 hours.

Redirected killing assay

A redirected killing assay was performed using the Fas-negative cell line L1210 as target cells. Target cells were labeled with 100 μCi (3.7 × 106 Bq) of 51Cr for 1 hour at 37°C, biotinylated with 0.2 mM N-hydroxysuccinimide long-chain biotin (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) for 30 minutes at 4°C, and streptavidin coated by incubation with 20 μg/mL of streptavidin (Sigma, St Louis, MO) for 30 minutes at room temperature. To study the role of the granule exocytosis pathway in the cytotoxicity to targets cells, memory CD4 T cells were pretreated with concanamycin A (CMA; 1 μM) for 2 hours before target cells were added to the culture. Target cells were mixed with memory CD4 T cells and 2.5 μg/mL of biotinylated anti-CD3 to redirect killing, and 51Cr release was evaluated after 4 hours.

Dextran assay

Memory CD4/CD80acq T cells were radiolabeled with 50 μCi (1.85 × 106 Bq) of 111In oxyquinoline solution (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) for 20 minutes at 37°C. Cells were cultured with or without 5% dextran (2 × 105 cells/well) for 4 hours. Supernatants were collected and radioactivity was quantitated.

RNase protection assay (RPA)

Total RNA was isolated from naive T cells and memory CD4/CD80acq T cells using STAT-60 reagent (TEL-TEST, Friendswood, TX). mRNA of apoptotic genes and cytokines was detected using RiboQuant multiple-probe RNase protection assay system (probe templates: mApo1, 2, 3 and mCK-1b; PharMingen) as described by the manufacturer. The net counts per minute (cpm) for a given band was calculated by the following formula, (cpm of cytokine gene − cpm of background), and was expressed as a percentage of the housekeeping gene transcript L32.

Apoptosis assay

Apoptosis was assessed using the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) kit (PharMingen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Annexin V staining was performed using the TACS annexin V–FITC kit from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) following the manufacturer's protocol.

In vivo studies

PCC TCR-Tg mice were vaccinated subcutaneously with 100 μg of PCC in alum. Animals were killed 1, 3, or 5 days after vaccination, and cells from lymph nodes (LNs) were analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis. For blocking experiments, animals were given 200 μg (100 μg intraperitoneally, 100 μg subcutaneously at site of vaccination) of anti-CD80 antibody (16-10A1; BD Biosciences PharMingen), anti-CD28 antibody, or isotype control antibody at the time of vaccination.

CFSE labeling and adoptive transfer studies

Memory CD4 T cells from DO11.10 mice were generated similarly as described before,9 with 10 μM OVA323-339 peptide. Memory DO11.10 CD4 T cells were labeled with 1 μM CFSE (5-(and-6)-carboxyfluoresceindiacetate-succinimidyl-ester) and adoptively transferred to either syngeneic Balb/c mice or syngeneic B7DKO mice (1 × 107 T cells intraperitoneally/mouse). Two weeks after the adoptive transfer, mice were vaccinated with 50 μg of OVA323-339 peptide in alum subcutaneously. Mice were killed 2 days later and spleen cells were analyzed by FACS.

Results

Kinetics of CD28-mediated acquisition of APS by memory CD4 T cells

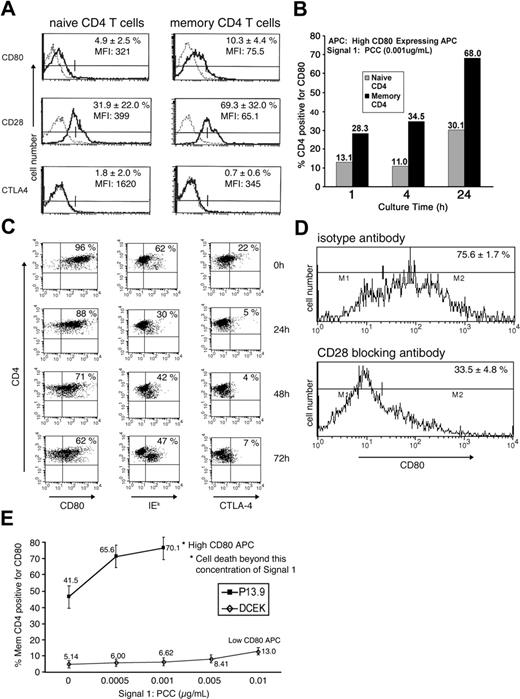

Memory CD4 T cells were generated and rested in vitro as described previously.9 To determine the expression of CD80, CD28, and CTLA-4 on the in vitro–rested memory CD4 T cells before further assays, these memory CD4 T cells were compared with freshly isolated naive CD4 T cells by FACS analysis. The percent of cells positive for CD80 slightly increased from 5% to 10% as naive CD4 T cells became memory T cells. The expression of CD28 (major receptor for CD80) increased from 32% in naive CD4 T cells to 69% in memory T cells. Expression of CTLA-4, which binds CD80 with high avidity, was very low (around 1%-2%; Figure 1A).

Characterization of differential acquisition of CD80 by memory CD4 T cells. (A) Memory CD4 T cells were generated as described in “Materials and methods,” under “Generation of CD4 T cells in culture and acquisition of CD80.” Naive and memory CD4 T cells were stained for the markers CD80, CD28, and CTLA-4 (solid line) or respective isotype control (dashed line) and FACS analyzed. Graphs are representative of 4 experiments and the percentage represents the average of positive cells with standard deviation (SD). (B) Naive or memory CD4 T cells (1 × 106) were cultured with 1 × 105 (high-CD80–expressing fibroblasts) APCs in the presence of 0.001 μg/mL PCC for the indicated time and analyzed for CD80 acquisition. Data are representative of multiple repeats. (C) Memory CD4 T cells (1 × 106) were cultured with 1 × 105 (high-CD80–expressing fibroblasts) APCs in the presence of 0.001 μg/mL PCC. Following incubation for 24 hours, cells were separated from APCs and cultured in the absence of APCs and PCC. FACS analysis was performed for CD4 and CD80, IEk, and CTLA-4 markers at indicated time points. Data are representative of 3 repeats. (D) Memory CD4 T cells were treated with either 20 μg/mL of anti-CD28 (bottom panel) or isotype control (top panel) antibody and then cultured with APCs and PCC (0.001 μg/mL) for 24 hours. Data are representative of 2 repeats. (E) Memory CD4 T cells (1 × 106) were cultured with either APCs expressing very low levels of CD80 (DCEK, ⋄) or APCs expressing high levels of CD80 (P13.9, ▪) with varying concentrations of PCC. Experiments were repeated 3 times and values are averages with SD. *Dead-cell FACS profile in the memory CD4 T-cell population.

Characterization of differential acquisition of CD80 by memory CD4 T cells. (A) Memory CD4 T cells were generated as described in “Materials and methods,” under “Generation of CD4 T cells in culture and acquisition of CD80.” Naive and memory CD4 T cells were stained for the markers CD80, CD28, and CTLA-4 (solid line) or respective isotype control (dashed line) and FACS analyzed. Graphs are representative of 4 experiments and the percentage represents the average of positive cells with standard deviation (SD). (B) Naive or memory CD4 T cells (1 × 106) were cultured with 1 × 105 (high-CD80–expressing fibroblasts) APCs in the presence of 0.001 μg/mL PCC for the indicated time and analyzed for CD80 acquisition. Data are representative of multiple repeats. (C) Memory CD4 T cells (1 × 106) were cultured with 1 × 105 (high-CD80–expressing fibroblasts) APCs in the presence of 0.001 μg/mL PCC. Following incubation for 24 hours, cells were separated from APCs and cultured in the absence of APCs and PCC. FACS analysis was performed for CD4 and CD80, IEk, and CTLA-4 markers at indicated time points. Data are representative of 3 repeats. (D) Memory CD4 T cells were treated with either 20 μg/mL of anti-CD28 (bottom panel) or isotype control (top panel) antibody and then cultured with APCs and PCC (0.001 μg/mL) for 24 hours. Data are representative of 2 repeats. (E) Memory CD4 T cells (1 × 106) were cultured with either APCs expressing very low levels of CD80 (DCEK, ⋄) or APCs expressing high levels of CD80 (P13.9, ▪) with varying concentrations of PCC. Experiments were repeated 3 times and values are averages with SD. *Dead-cell FACS profile in the memory CD4 T-cell population.

To investigate CD80 acquisition by CD4 T cells, either naive or memory CD4 T cells were cultured with 0.001 μg/mL of PCC and APCs (expressing a high amount of CD80, as described earlier9,12 ). Previously, we demonstrated that CD80 acquisition is enhanced in memory CD4 T cells.9 In order to address the kinetics of the observed CD80 acquisition, naive or memory CD4 T cells were cultured for 1, 4, or 24 hours in this study. As depicted in Figure 1B, the CD4 T cells started to acquire CD80 within 1 hour of coculture with APCs in the presence of 0.001 μg/mL of PCC. The number of CD4 T cells with acquired CD80 increased over time; the percentage of memory CD4 T cells with acquired CD80 was at all time points more than double the percentage of naive CD4 T cells, reaching 68% at 24 hours (Figure 1B). In order to look at the long-term kinetics of APS acquisition, memory CD4 cells with acquired APS (CD4/CD80acq T cells) were separated from APCs after 24 hours of activation and left in culture in the absence of PCC for various time points. As depicted in Figure 1C, by 72 hours, two thirds of CD4/CD80acq T cells still expressed CD80 (compared with 0 hour); expression of MHC class II-IEk was reduced from 62% to 47%. CTLA-4 expression in CD4/CD80acq T cells reduced from 22% (at point of separation from APCs) to 7% by 72 hours.

To further investigate if increased acquisition of CD80 by memory CD4 T cells is due to the enhanced expression of CD28 on memory CD4 T cells compared with the expression level on naive cells, the memory CD4 T cells were either treated with anti-CD28 blocking antibody or isotype control antibody and were cultured with 0.001 μg/mL of PCC and APCs (expressing high levels of CD809 ) for 24 hours to acquire CD80 and MHC class II molecules. Consistent with our previous observations in CD28KO mice,9 treatment of the memory CD4 T cells with anti-CD28 antibody led to inhibition of CD80 acquisition from 76% to 34% compared with blocking with isotype control, indicating that the acquisition of CD80 is mediated by CD28 for memory CD4 T cells (Figure 1D). Furthermore, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) studies demonstrated that upon acquisition of CD80 by memory CD4 T cells, there was no endogenous up-regulation of CD80 (data not shown).

Amount of CD80 acquired by memory CD4 T cells is dependent on CD80 expression on APCs

Studies were undertaken to investigate whether increased density of CD80 on APCs might affect the acquisition of CD80 by memory CD4 T cells. As depicted in Figure 1E, the amount of CD80 acquired by effector/memory CD4 T cells is directly dependent on the amount of CD80 expressed on the APCs. When memory CD4 T cells were cocultured with APCs (expressing a high amount of CD80) in the presence of PCC for 24 hours (0.001 μg/mL), 70% of the cells acquired CD80. Interestingly, increased concentration of PCC in the presence of APCs led to apoptosis of these cells.9 When memory CD4 T cells were cocultured with APCs that expressed low levels of CD80 (DCEK; 8%-10% express CD80) in the presence of various amounts of peptide, they acquired very little CD80 from these cells (5%-13%; Figure 1E). An increased amount of signal 1 (PCC) did not lead to apoptosis of these cells. Moreover, memory CD4 T cells could acquire high amounts of CD80 in the absence of PCC. This phenomenon is related to the high expression of CD28 on the surface of memory CD4 T cells and the high amounts of CD80 on the surface of the APCs in this study. These results indicate that the expression of CD80 on APC surface plays a role in the amount of CD80 acquired by memory CD4 T cells.

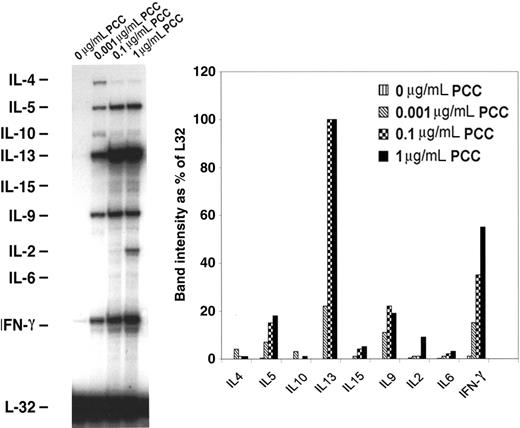

Expression of cytokines by memory CD4 T cells restimulated after acquisition of APS

In order to examine the differentiation of memory CD4 T cells into T-helper 1 (Th1)/Th2 upon acquisition of APS, memory CD4/CD80acq T cells were restimulated with APCs expressing high amounts of CD80 in the presence of various concentrations of peptides for 24 hours and then purified and used in RPAs. As depicted in Figure 2, upon reactivation with PCC ranging from 0.001 to 1 μg/mL of peptide, these cells expressed enhanced levels of the Th1 cytokine interferon γ (IFN-γ) and Th2 type cytokines such as IL-5, IL-13, IL-9, and IL-2. This result indicates that these CD4 T cells have mixed Th1/Th2 characteristics.

mRNA expression of cytokine genes by memory CD4/CD80acq T cells. Memory CD4/CD80acq T cells were restimulated for 24 hours in the presence of APCs and the indicated concentrations of PCC and separated from APCs, and their RNA was analyzed by RPA. All samples were analyzed with a Th1/Th2 RPA probe set, and band intensity was calculated based on the housekeeping gene L32.

mRNA expression of cytokine genes by memory CD4/CD80acq T cells. Memory CD4/CD80acq T cells were restimulated for 24 hours in the presence of APCs and the indicated concentrations of PCC and separated from APCs, and their RNA was analyzed by RPA. All samples were analyzed with a Th1/Th2 RPA probe set, and band intensity was calculated based on the housekeeping gene L32.

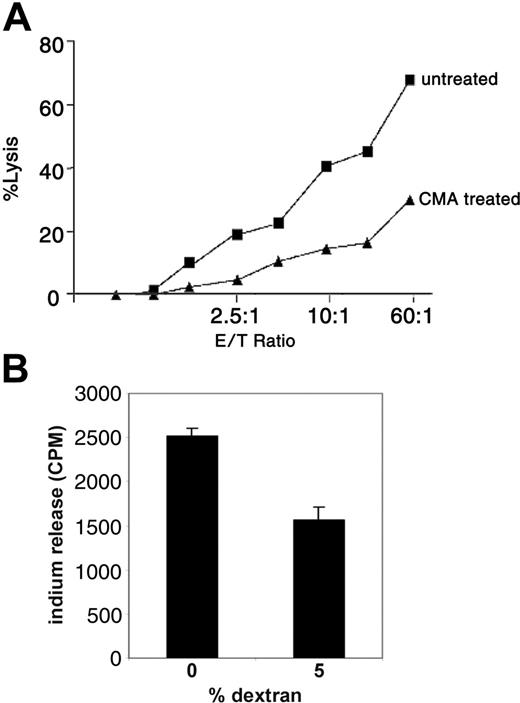

CTL activity of memory CD4 T cells upon acquisition of APS

In a previous study it was suggested that the perforin pathway may act as a regulator of T-cell homeostasis.14 To address if acquisition of APS can lead to enhanced cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) activity in memory CD4/CD80acq T cells via the granule exocytosis pathway, these cells were used as effector cells in a redirected killing assay using the FAS-negative cell line L1210 as target cells. As depicted in Figure 3A, memory CD4/CD80acq T cells were able to lyse the FAS-negative target cells very efficiently. When memory CD4/CD80acq T cells were treated with CMA, which inhibits the vacuolar type H+ ATPase and leads to perforin degradation in the cell,15 their ability to lyse the target cells was strongly diminished.

Memory CD4/CD80acq T cells exhibit CTL activity through the perforin pathway. (A) Memory CD4/CD80acq T cells were used in a redirected killing assay in the presence (▴) or absence (▪) of concanamycin A (CMA). E/T indicates effector–T-cell ratio. (B) Memory CD4/CD80acq T cells were labeled with 111In and cultured in the absence or presence of 5% dextran (2 × 105 cells/well) for 4 hours. Supernatants were harvested and counted for 111In release. Data are representative of 2 repeats. Values are average of 3 wells with SE (standard error of mean).

Memory CD4/CD80acq T cells exhibit CTL activity through the perforin pathway. (A) Memory CD4/CD80acq T cells were used in a redirected killing assay in the presence (▴) or absence (▪) of concanamycin A (CMA). E/T indicates effector–T-cell ratio. (B) Memory CD4/CD80acq T cells were labeled with 111In and cultured in the absence or presence of 5% dextran (2 × 105 cells/well) for 4 hours. Supernatants were harvested and counted for 111In release. Data are representative of 2 repeats. Values are average of 3 wells with SE (standard error of mean).

To analyze the functional significance of the CTL activity after APS acquisition, memory CD4/CD80acq T cells were labeled with 111In and cultured in media in the absence of peptide. When 5% dextran (used to separate the cells and reduce the T-cell–T-cell interaction without affecting their characteristics) was added to the cultures, spontaneous lysis of these cells was strongly reduced (Figure 3B). This result suggests that memory CD4/CD80acq T cells that exhibit CTL activity have the ability to kill neighboring T cells through fratricide.

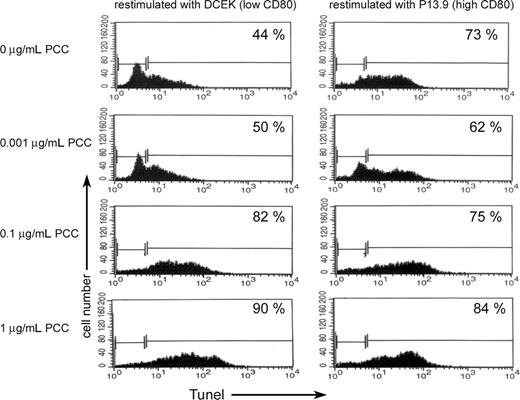

In vitro reactivation of memory CD4 T cells that had acquired APS leads to apoptosis

Previously we demonstrated that memory CD4 T cells can acquire significantly higher levels of APS compared with naive CD4 T cells and undergo apoptosis upon acquisition of APS.9 In order to see if memory CD4 T cells that had acquired APS and survived are more resistant to apoptosis upon reactivation, live memory CD4 T cells that had acquired APS from APCs in the presence of PCC (0.001 μg/mL) were separated from APCs. The surviving CD4/CD80acq T cells were reactivated for 24 hours with either APCs that express low levels of CD80 (fibroblasts expressing low levels of CD80; DCEK) or APCs that express high levels of CD80 (fibroblasts expressing high levels of CD80; P13.9) in the absence or presence of various concentrations of PCC. As demonstrated in the left panel of Figure 4, in the absence of PCC, 44% of memory CD4/CD80acq T cells that were restimulated with low-CD80–expressing APCs underwent apoptosis versus 73% of the memory CD4/CD80acq T cells that were cocultured with APCs that express a high amount of CD80 (Figure 4 right panel). Increasing the strength of signal 1 led to increased apoptosis of memory CD4/CD80acq T cells that were reactivated with APCs expressing low levels of CD80 (Figure 4 left panel). Increasing the strength of signal 1 in the presence of high costimulation through CD80 (APCs expressing high levels of CD80) did not play a major role in enhanced apoptosis of memory CD4/CD80acq T cells (Figure 4 right panel).

Apoptosis of memory CD4 cells with and without acquisition of CD80. Memory CD4/CD80acq T cells were restimulated overnight either with APCs expressing low levels of CD80 (DCEK) or APCs expressing high levels of CD80 (P13.9) in the presence of various concentrations of PCC (0, 0.001, 0.1, and 1 μg/mL). Each panel depicts the percentage of apoptotic cells by TUNEL assay.

Apoptosis of memory CD4 cells with and without acquisition of CD80. Memory CD4/CD80acq T cells were restimulated overnight either with APCs expressing low levels of CD80 (DCEK) or APCs expressing high levels of CD80 (P13.9) in the presence of various concentrations of PCC (0, 0.001, 0.1, and 1 μg/mL). Each panel depicts the percentage of apoptotic cells by TUNEL assay.

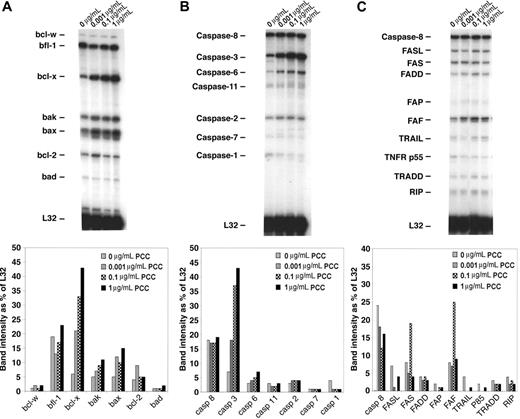

Expression of apoptotic genes and proteins upon reactivation of memory CD4 T cells that had acquired APS

To demonstrate which pathways are involved in apoptosis of memory CD4/CD80acq T cells, we used RPAs. Memory CD4/CD80acq T cells were reactivated in the presence of APCs expressing high levels of CD80 and various concentrations of peptide (as described in “In vitro reactivation of memory CD4 T cells that had acquired APS leads to apoptosis”) and separated from APCs, and their RNA was analyzed by RPA. Our results demonstrated that upon reactivation of effector CD4/CD80acq T cells, bax and bak were up-regulated (Figure 5A) compared with control cells cultured without PCC. Also, the bcl-x gene (including both bcl-xL and bcl-xS) was markedly up-regulated upon reactivation of CD4/CD80acq memory T cells. bcl-x and bak up-regulation was directly related to the peptide concentration (Figure 5A lanes 1-4). When we looked at the expression of caspases in the same samples, there was a strong up-regulation of caspase 3 in samples that were reactivated with PCC; this increase seems to be dependent on peptide concentration (Figure 5B lanes 2-4). However, the expression of other caspases was not changed in any of the other samples regardless of whether the memory CD4/CD80acq T cells were reactivated or not. As depicted in Figure 5C, there were no consistent changes in the expression of genes of the FAS pathway after reactivation of memory CD4 T cells that had acquired APS. Western-blot analysis confirmed these results (data not shown).

Analysis of apoptotic pathways in memory CD4/CD80acq T cells. Memory CD4/CD80acq T cells were cultured in the presence of APCs and indicated concentrations of PCC and separated from APCs, and their RNA was analyzed by RPA. All samples were analyzed with RPA probe set (mApo1, 2, 3), and band intensity was calculated based on the housekeeping gene L32.

Analysis of apoptotic pathways in memory CD4/CD80acq T cells. Memory CD4/CD80acq T cells were cultured in the presence of APCs and indicated concentrations of PCC and separated from APCs, and their RNA was analyzed by RPA. All samples were analyzed with RPA probe set (mApo1, 2, 3), and band intensity was calculated based on the housekeeping gene L32.

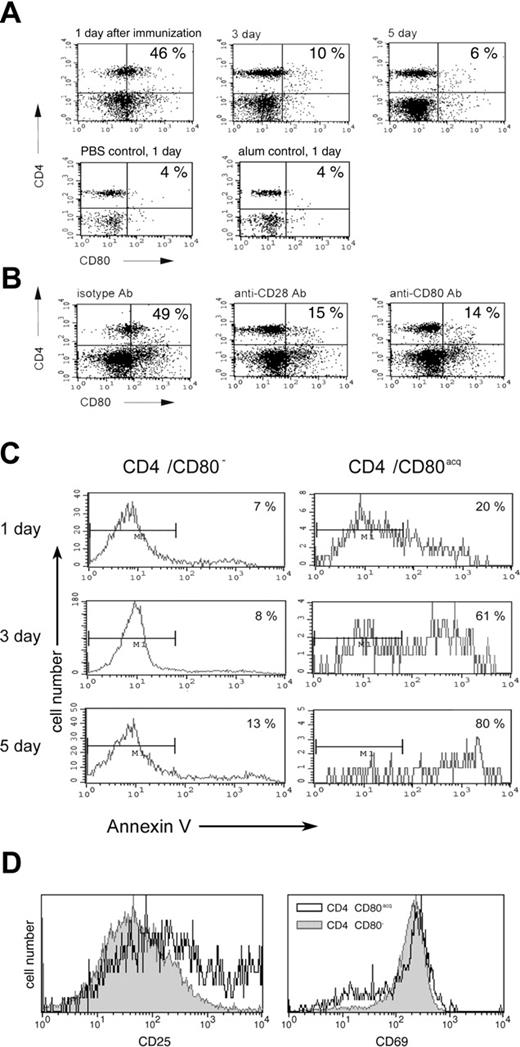

In vivo acquisition of CD80 by CD4 T cells and its physiologic consequences on T-cell activation and apoptosis

In order to determine whether CD80 can be acquired by naive CD4 T cells upon vaccination in vivo and to investigate the physiologic consequence of this phenomenon, PCC TCR-Tg mice were vaccinated subcutaneously with peptide and adjuvant (100 μg of PCC with alum). Control mice were either treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or adjuvant alone (alum) or did not receive any treatment. Animals were killed 1, 3, and 5 days after vaccination, and T cells from LNs and spleens were analyzed for CD4 and CD80 expression. As depicted in Figure 6A, approximately 46% of CD4 T cells from LNs displayed CD80 on their surface 1 day after vaccination. At the same time, control mice treated with PBS or alum showed no increase in CD4/CD80acq T cells compared with untreated animals (Figures 1A and 6A). Three days and 5 days after vaccination, the number of CD4/CD80acq cells was strongly reduced in LNs (6%-10%). Similar results were seen in splenic lymphocytes. At 1 day after vaccination with PCC in alum, approximately 35% to 40% of CD4 T cells in spleen displayed CD80 on their surface; mice treated with PBS or alum, however, displayed only 3% and 4%, respectively, of CD4/CD80acq cells (data not shown). To provide further evidence that CD4 T cells that exhibit CD80 had acquired this molecule, PCC TCR-Tg mice were vaccinated with PCC and alum adjuvant and treated with antibodies to either CD28 or CD80 (antibodies were given 100 μg subcutaneously and 100 μg intraperitoneally) to block acquisition of CD80 from APCs. Mice were killed 12 hours after vaccination and CD4 T cells were separated from LNs. As depicted in Figure 6B, in mice that received anti-CD28 antibody at the time of vaccination with PCC plus alum, only 15% of CD4 T cells in LNs acquired CD80 at 12 hours (Figure 6B). When mice that were vaccinated with PCC and alum received anti-CD80 at the time of vaccination, only 14% of CD4 T cells acquired CD80 (Figure 6B). To eliminate the possibility that the anti-CD80 antibody used in in vivo study blocks the detection of CD80 in FACS analysis, a different clone of anti-CD80 antibody was used to detect the expression of CD80 on T cells. Treatment of vaccinated mice with isotype control mAbs did not affect the acquisition of CD80 (Figure 6B).

Physiologic consequence of CD80 acquisition by T cells in vivo. (A) The acquisition of CD80 by CD4 T cells was examined after PCC TCR-Tg mice were vaccinated with peptide/adjuvant (PCC in alum) and killed 1, 3, or 5 days after vaccination. T cells from LNs were analyzed for CD80 acquisition by FACS. (B) PCC-vaccinated PCC TCR-Tg mice were treated either with anti-CD28 antibody, anti-CD80 antibody, or isotype antibody (100 μg intraperitoneally and 100 μg subcutaneously) at the time of vaccination. Animals were killed 1 day later and their LNs were analyzed by FACS. (C) PCC-vaccinated PCC TCR-Tg mice were killed on indicated days after vaccination and T cells from LNs were analyzed for CD4, CD80, and annexin V (to identify the apoptotic cells) by FACS. (D) PCC-vaccinated PCC TCR-Tg mice were killed 1 day after vaccination and T cells from LNs were analyzed for CD69 and CD25 expression on CD4/CD80acq (open histogram) or CD4/CD80− (closed gray histogram) T cells by FACS.

Physiologic consequence of CD80 acquisition by T cells in vivo. (A) The acquisition of CD80 by CD4 T cells was examined after PCC TCR-Tg mice were vaccinated with peptide/adjuvant (PCC in alum) and killed 1, 3, or 5 days after vaccination. T cells from LNs were analyzed for CD80 acquisition by FACS. (B) PCC-vaccinated PCC TCR-Tg mice were treated either with anti-CD28 antibody, anti-CD80 antibody, or isotype antibody (100 μg intraperitoneally and 100 μg subcutaneously) at the time of vaccination. Animals were killed 1 day later and their LNs were analyzed by FACS. (C) PCC-vaccinated PCC TCR-Tg mice were killed on indicated days after vaccination and T cells from LNs were analyzed for CD4, CD80, and annexin V (to identify the apoptotic cells) by FACS. (D) PCC-vaccinated PCC TCR-Tg mice were killed 1 day after vaccination and T cells from LNs were analyzed for CD69 and CD25 expression on CD4/CD80acq (open histogram) or CD4/CD80− (closed gray histogram) T cells by FACS.

To demonstrate the role of CD80 acquisition in the regulation of the effector cell population, the CD4 T cells from the LNs of PCC TCR-Tg–vaccinated mice (PCC + alum) were analyzed for apoptosis 1, 3, and 5 days after vaccination. As depicted in the left panel of Figure 6C, CD4 T cells that did not acquire CD80 showed very little apoptosis at either 1, 3, or 5 days after vaccination (7%-13%). In comparison, the CD4/CD80acq T cells showed higher apoptosis (Figure 6C right panel; 20%-80%). Comparison of early activation markers on CD4/CD80− and CD4/CD80acq T cells 1 day after immunization in LNs revealed that both populations expressed similar levels of CD69. However, CD4/CD80acq cells expressed slightly higher levels of CD25 (Figure 6D). These experiments demonstrate not only that CD4 T cells can acquire CD80 in vivo but also that the acquisition of CD80 by effector cells correlates with increased apoptosis of these cells.

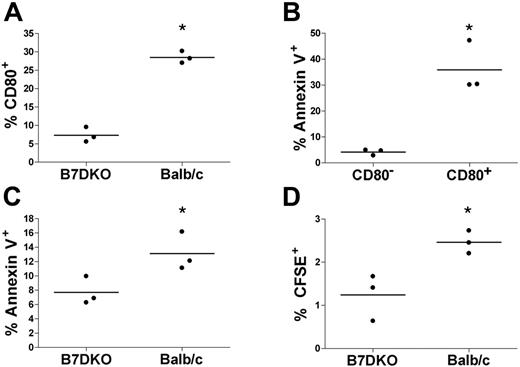

To assess the role of CD80 acquisition on the fate of memory CD4 T cells in vivo, memory CD4 T cells (generated in vitro) were CFSE labeled and adoptively transferred into host mice and rested for 2 additional weeks in vivo. We used DO11.10 CD4 T cells, which express a TCR specific for OVA323-339, and either syngeneic Balb/c mice or syngeneic B7DKO mice, which are double knockout mice for CD80 and CD86, as hosts. Two weeks after adoptive transfer, mice were vaccinated with OVA323-339 in alum, and 2 days later mice were killed and spleen cells were analyzed. As shown in Figure 7A, about 28% of transferred memory CD4 T cells were CD80+ in the Balb/c hosts compared with about 7% in the B7DKO mice (P < .05). This demonstrates that the majority of the CD80+ memory CD4 T cells had acquired their CD80 from host cells and not produced it endogenously. Moreover, a significantly higher percentage of these CD4/CD80acq cells in Balb/c hosts were annexin V positive compared with the memory CD4 T cells that remained CD80− (Figure 7B; P < .01). This is in agreement with data shown in Figure 6C and demonstrates that acquisition of CD80 is correlated with higher apoptosis in vivo, similar to our previously published in vitro results.9 Overall, the adoptively transferred memory CD4 T cells showed a significantly higher rate of apoptosis in the Balb/c hosts than in the B7DKO hosts (Figure 7C; P < .05). Moreover, we observed a significantly higher percentage of adoptively transferred memory CD4 T cells in the spleens of Balb/c hosts than in the B7DKO hosts (2.5% vs 1.2%, P < .05; Figure 7D).

Physiologic consequence of CD80 acquisition by memory T cells in vivo. CFSE-labeled DK11.10 memory CD4 T cells were adoptively transferred into either Balb/c or B7DKO mice and rested for 2 more weeks in vivo. Animals were then vaccinated with OVA323-339/adjuvant (alum) and killed 2 days later. CFSE-labeled cells from spleen were analyzed by FACS. Every dot in the graph represents 1 animal. Horizontal bars indicate average. *A statistically significant difference (t test, P < .05). (A) CFSE-labeled cells in B7DKO or Balb/c hosts were analyzed for CD80 acquisition. (B) CFSE-labeled cells in Balb/c hosts were analyzed for CD80 and annexin V. (C) CFSE-labeled cells in B7DKO and Balb/c hosts were analyzed for annexin V. (D) The percentage of CFSE-labeled cells in B7DKO and Balb/c hosts was analyzed.

Physiologic consequence of CD80 acquisition by memory T cells in vivo. CFSE-labeled DK11.10 memory CD4 T cells were adoptively transferred into either Balb/c or B7DKO mice and rested for 2 more weeks in vivo. Animals were then vaccinated with OVA323-339/adjuvant (alum) and killed 2 days later. CFSE-labeled cells from spleen were analyzed by FACS. Every dot in the graph represents 1 animal. Horizontal bars indicate average. *A statistically significant difference (t test, P < .05). (A) CFSE-labeled cells in B7DKO or Balb/c hosts were analyzed for CD80 acquisition. (B) CFSE-labeled cells in Balb/c hosts were analyzed for CD80 and annexin V. (C) CFSE-labeled cells in B7DKO and Balb/c hosts were analyzed for annexin V. (D) The percentage of CFSE-labeled cells in B7DKO and Balb/c hosts was analyzed.

Discussion

In this report, we demonstrate that memory CD4 T cells can acquire APS both in vitro and in vivo from APCs. Expression of CD80 in memory T cells after activation is not de novo because no CD80 transcript could be detected by PCR at the time of acquisition of CD80 by memory CD4 T cells. Previously, we have demonstrated that memory CD4 T cells that had acquired CD80 in the presence of a high concentration of antigen (signal 1) undergo apoptosis.9 Our current result further indicates that up-regulation of bax, bak, and caspase 3 is associated with the apoptosis of these cells. Furthermore, for the first time these studies show that CD80 can be acquired in vivo by CD4 T cells upon vaccination with peptide and also that in vivo memory CD4/CD80acq T cells undergo higher levels of apoptosis compared with memory CD4 T cells that had not acquired CD80. The cytokine profile of memory CD4/CD80acq cells demonstrates that these cells have a mixed Th1 and Th2 profile upon restimulation. Interestingly, these CD4 T cells can exhibit CTL activity and kill other cells through perforin-mediated fratricide.

During initial contact with antigen, naive T cells proliferate and differentiate into activated memory T cells. Division of antigen-specific T cells during the height of immune response is very fast and leads to a significant expansion of the T cells within a few days. Once the antigen is cleared, these effector T cells reduce rapidly and a small percentage (4%-5%) will become what is referred to as stable memory cells.16 Failure of the effective removal of effector cells could lead to immunodeficiency, autoimmunity, and accumulation of lymphocytes. The mechanisms that lead to the contraction of effector cells and generation of long-term memory have become an important issue in the field of immunology. One hypothesis states that the removal of antigen-bearing APCs may lead to the cessation of clonal expansion and eventually clonal deletion; however, a number of studies have demonstrated that T cells can undergo several rounds of division after being deprived of contact with APCs.17–20 To explain this conundrum, we recently demonstrated that naive CD4 T cells upon acquisition of CD80 and MHC molecules are capable of sustaining the transcriptional activation signals and proliferative response in the absence of APCs and exogenous antigen.9,10,12

Another potentially important mechanism in the contraction of effector CD4 T cells might include CTLA-4 and programmed cell death 1 (PD1) as the checkpoint.21–24 However, in our studies, only 22% of CD4/CD80acq T cells express CTLA-4 in vitro at the time of separation, and this population drops to 5% to 7% after separation from APCs. Moreover, in vivo less than 2% to 3% of CD4/CD80+ T cells express CTLA-4 (data not shown). These data in combination with the fact that blocking of CTLA-4 by either antibody or fusion protein did not reduce the level of apoptosis of memory CD4/CD80acq cells in vitro (data not shown) suggest that CTLA-4 might not be the main regulatory mechanism in this setting.

Previously, we have demonstrated that the addition of anti-CD80 antibody to memory CD4/CD80acq T cells rescues some of these cells from apoptosis, perhaps by blocking the interaction of T cells with each other.9 In this study, we demonstrate that these CD4 T cells are capable of killing other T cells through perforin-related mechanisms as demonstrated in our redirected killing assays and dextran assay. It has been demonstrated that the perforin-mediated pathway can down-regulate T-cell responses during chronic viral infection.25 Badovinac et al14 conclude that perforin is a regulator during CD8 T-cell expansion and IFN-γ plays a major role in the CD8 T-cell contraction at the end of the immune response. Our findings, showing the perforin-mediated cell death of memory CD4/CD80acq T cells, expand this hypothesis to the CD4 T-cell population and the role of APS acquisition in the initiation of CTL activity in the memory CD4/CD80acq T cells. Cytotoxic CD4 T cells that use the perforin pathway supposedly play an important role in immune reactions against parasites or some viruses.26–28 However, this is the first demonstration that CTL activity by memory CD4/CD80acq T cells might play a role in regulating the T-cell expansion phase. In addition, we here demonstrated that memory CD4/CD80acq T cells contain both Th1 and Th2 cell types, as we observed the production of both Th1 (IFN-γ) and Th2 (IL-4, IL-13, and IL-9) cytokines from these cells. Restimulation of these memory CD4/CD80acq T cells induced the production of IFN-γ, which may facilitate the elimination of these cells.14,29

Numerous studies have suggested that the deletion of effector CD8 T cells is not dependent on Bcl-2, Bcl-X, CTLA-4, FAS, TNRR, or perforin.30–33 In this study, we observed that memory CD4/CD80acq T cells that are undergoing apoptotic death up-regulate bak, bax, and caspase genes (executors of death) in the presence of signal 1.

Our results suggest that the acquisition of APS by memory T cells can lead to negative regulatory consequences by activating the BAX/BAK and perforin pathways that can lead to cell death in vitro. Even though our results show an increase in expression of bcl-x, it has been demonstrated that bcl-x is dispensable for the generation of effector and memory T lymphocytes.34 Furthermore, our in vivo studies for the first time demonstrate that CD80 acquisitions indeed occur in vivo in a manner similar to in vitro acquisition.

Our results demonstrate that the acquisition of APS by either recently activated effector T cells or more established long-term memory T cells correlates with their sensitivity to apoptotic cell death; T cells that have acquired APS are more prone to apoptosis. Collectively, our observations may shed a new light on the role of acquired APS and elimination of memory T cells in a FAS-independent manner.

It has been hypothesized that long-term memory cells are generated by a default pathway and represent a few memory T-cell escapees that evade being signaled to die by multiple cell-death–inducing mechanisms.2,3 In light of this hypothesis, we suggest that acquisition of costimulatory molecules and MHC (APS) by T cells at an early phase of activation leads to the activation and proliferation of these cells. However, as T cells enter the memory phase and acquire more APSs, they might start to interact with one another. The interaction among memory CD4/CD80acq T cells could lead to eradication of the majority of these cells through replicative cessation, apoptosis, or even CTL mechanisms. The few activated T cells that do not come in contact with these memory CD4/CD80acq T cells can be seen as the few escapees that will turn into long-term memory T cells. Therefore, APS acquisition can act as a checkpoint for memory CD4 T-cell homeostasis, which decides the outcome of CD4 T-cell activation.

Authorship

Contribution: S.M. designed and performed the research and wrote the manuscript. Y.T. and M.C. participated in designing and performing the research. J.S. participated in designing the research and writing the manuscript. H.S. designed and performed the research and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jeffrey Schlom, Bldg 10, Rm 8B09, Laboratory of Tumor Immunology and Biology, Center for Cancer Research, NCI, NIH, Bethesda, MD 20892; e-mail: js141c@nih.gov.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

The authors thank Judith DiPietro for her technical assistance and Debra Weingarten for her editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal