Abstract

Congenital erythropoietic porphyria (CEP), an autosomal recessive disorder, is due to mutations of uroporphyrinogen III synthase (UROS). Deficiency of UROS results in excess uroporphyrin I, which causes photosensitization. We evaluated a 3-year-old boy with CEP. A hypochromic, microcytic anemia was present from birth, and platelet counts averaged 70 × 109/L (70 000/μL). Erythrocyte UROS activity was 21% of controls. Red cell morphology and globin chain labeling studies were compatible with β-thalassemia. Hb electrophoresis revealed 36.3% A, 2.4% A2, 59.5% F, and 1.8% of an unidentified peak. No UROS or α- and β-globin mutations were found in the child or the parents. The molecular basis of the phenotype proved to be a mutation of GATA1, an X-linked transcription factor common to globin genes and heme biosynthetic enzymes in erythrocytes. A mutation at codon 216 in the child and on one allele of his mother changed arginine to tryptophan (R216W). This is the first report of a human porphyria due to a mutation in a trans-acting factor and the first association of CEP with thalassemia and thrombocytopenia. The Hb F level of 59.5% suggests a role for GATA-1 in globin switching. A bone marrow allograft corrected both the porphyria and the thalassemia.

Introduction

Congenital erythropoietic porphyria (CEP; OMIM no. 263700) is the most rare of the porphyrias and was the first form of porphyria described by Schultz in 1874.1 In 1911, Günther recognized the condition as an inborn error of metabolism,1 and CEP has since been referred to as Günther disease. There is considerable phenotypic variability, but most patients with CEP develop photosensitivity, red urine, and hirsutism soon after birth. Photomutilation eventually occurs in most cases. An associated anemia, splenomegaly, and erythrocytes that fluoresce under ultraviolet light complete the clinical phenotype. The anemia generally resembles congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type I (OMIM no. 224120).1 Erythrocyte fluorescence is due to high intracellular concentrations of uroporphyrin I (uro-I), which is transported to plasma and excreted in the urine. Excess plasma uro-I mediates the striking cutaneous photosensitivity in CEP.

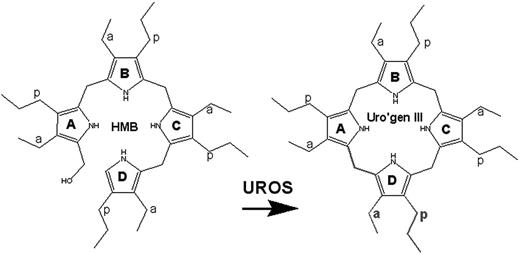

CEP is transmitted as an autosomal recessive trait. Patients with CEP are either homozygotes or compound heterozygotes for mutations of the UROS gene at 10q25.2-q26.3 that encodes uroporphyrinogen III synthase (UROS, EC 4.2.1.75), a cytosolic enzyme that converts hydroxymethyl bilane (HMB) to uroporphyrinogen III (Figure 1). Deficiency of UROS results in accumulation of HMB, most of which is converted nonenzymatically to uro-I, a biologically useless compound.

Generation of uroporphyrinogen III (uro'gen III) by uroporphyrinogen III synthase (UROS). The enzyme catalyzes the cyclization of HMB with concomitant inversion of ring D to yield the III isomer of uro'gen.10 a indicates acetate; p, propionate.

Generation of uroporphyrinogen III (uro'gen III) by uroporphyrinogen III synthase (UROS). The enzyme catalyzes the cyclization of HMB with concomitant inversion of ring D to yield the III isomer of uro'gen.10 a indicates acetate; p, propionate.

Here, we describe a 3-year-old boy with the clinical phenotype of CEP. The anemia did not resemble congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type I but did resemble thalassemia intermedia. Fetal hemoglobin (Hb F) was dramatically increased and moderate thrombocytopenia was present. We detected no mutations or rearrangements in UROS or in the globin genes or their major regulatory elements. Instead, we identified a novel germ line mutation in the X-linked erythroid-specific transcription factor GATA binding protein 1 (GATA-1).

Materials and methods

Porphyrin and enzymatic analysis

Urine porphyrins were quantified, and porphyrin isomers were separated as described.2 Activities of aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALA-D), porphobilinogen deaminase (PBG-D), uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (URO-D), and uroporphyrinogen III synthase (UROS) were measured in erythrocyte lysates using published methods.3–5

DNA analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from the peripheral blood. DNA was amplified using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and the UROS gene and its promoter were sequenced.8 DNA sequencing was bidirectional, using an ABI BigDye kit with an ABI Prism sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Globin gene analyses included direct sequencing of α, β, Gγ, and Aγ genes, and their promoter elements. For Southern blotting of the γ region, we used a 32P-labeled 489-bp (base pair) probe prepared by PvuII digestion from the second intron (IVS2) of the γ-globin gene (a gift of William G. Wood, Oxford, England). Genomic DNA was digested with EcoRI and HindIII restriction endonucleases. To analyze the α-globin cluster for rearrangements, we digested genomic DNA with BamHI and BglII and hybridized with radiolabeled 0.5-kb (kilobase) HindIII/PstI α-globin probe and ζ-globin probes (gifts of Douglas R. Higgs, Oxford, England). ATRX was screened for mutations using denaturing HPLC as described.9 The coding region of GATA1 was PCR amplified using oligonucleotide primers flanking each exon, and amplicons were sequenced bidirectionally using the same primers. Mutations were confirmed in separately amplified samples by restriction enzyme analysis.

Globin chain labeling

Mononuclear cells obtained by marrow aspiration were prepared using Histopaque-1077 (Sigma, St Louis, MO) and cryopreserved. Frozen vials were thawed, and cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, sodium pyruvate, glutamine, antibiotics, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, and cytokines (erythropoietin, 4 U/mL; steel factor, fms-like tyrosine kinase ligand, and thrombopoietin, all at 100 ng/mL). Cells were cultured overnight, then washed in PBS containing 1% BSA, and resuspended in 1 mL leucine-deficient RPMI-1640 (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) supplemented with 10% dialyzed fetal calf serum, 600 mg/L MgCl2, 150 μL of a 1 mg/mL solution of freshly prepared ferrous ammonium sulfate, and 10 U/mL erythropoietin. Following a 10-minute incubation at 37°C, 50 μCi (1.85 MBq) L-[4,5-3H]Leucine (155 Ci [573.5 × 1010 Bq]/mmol; Amersham) were added. Cells were incubated with the isotope for 60 minutes at 37°C, washed twice in PBS containing 1% BSA, and pelleted. Cells were lysed in 250 μL H2O overnight at 4°C. The membranes were then pelleted at 14 000g for 5 minutes. Globin chains were separated by HPLC as described by Schroeder et al10 except that a 250 × 4.6-mm C18 column with a 300 Å porosity (Jupiter Series; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) was used. Peaks for each of the globin chains were collected and diluted 10:1 with Ready Solve scintillant (Beckman, Fullerton, CA) and counted.

Image acquisition

The peripheral blood film image (Wright-Giemsa stain) was visualized using an Olympus BX 40 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a Uplan 100 ×/1.30 NA oil objective. The image was acquired with an Olympus Q-color 3 camera and processed using Adobe Photoshop version 7.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

Results

A 3-year-old boy of English-French extraction with a photosensitive bullous dermatosis was referred to the Porphyria Research Clinic at the University of Utah's General Clinical Research Center. CEP was suspected. The Institutional Review Boards of the University of Utah and the Mayo Clinic approved all studies. The patient's parents and family members provided written consent for the DNA and enzymatic analyses.

At birth, the boy had hypochromic, microcytic anemia, and thrombocytopenia. Average hematologic parameters over the subsequent 3 years were as follows: hemoglobin (Hb) level, 70.0 g/L; mean corpuscular volume (MCV), 67 fL; mean corpuscular hemoglobin level, consistently less than 20 pg; and platelet level, 70 × 106/L. Reticulocyte counts ranged from 3.6% to 6.7%. Iron studies were unremarkable. He was small for his age. A physical examination revealed scars on the face, hands, and forearms; generalized hirsutism; and splenomegaly. The diapers exhibited brilliant pink fluorescence when illuminated with long-range ultraviolet light. A 50-mL urine sample contained 2003 μg uroporphyrin (normal, trace); 92% of this was uro-I. Fluorescent red cells were detected using a microscope fitted with a 405 nm light source. Erythrocyte UROS activity was 21% of the normal mean. Collectively, these findings confirmed the diagnosis of CEP.

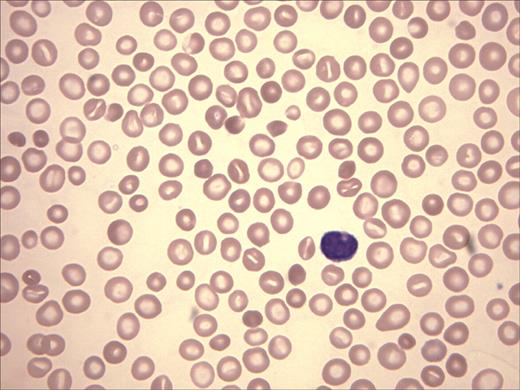

The patient's peripheral-blood smear revealed microcytic, hypochromic red cells, target cells, basophilic stippling, and rare nucleated red cells, findings compatible with thalassemia (Figure 2). Platelets, although reduced in number, were morphologically normal, and leukocytes also appeared normal. A bone marrow aspirate and biopsy revealed a hypercellular marrow (cellularity, 90%-100%) and erythroid hyperplasia (M/E ratio, 0.6). Dyserythropoiesis was noted with nuclear budding, nuclear bridging, and occasional multinucleation. Megakaryocytes were decreased in number with occasional small, hypolobate forms. Hb electrophoresis revealed 36.3% Hb A, 2.4% Hb A2, 59.5% Hb F, and 1.8% of an unidentified peak moving at the solvent front.

Wright-Giemsa stain of peripheral-blood film. Anisocytosis, hypochromia, target cells, and polychromasia are evident.

Wright-Giemsa stain of peripheral-blood film. Anisocytosis, hypochromia, target cells, and polychromasia are evident.

Both parents were hematologically normal, had no evidence of porphyria, and had normal Hb electrophoreses, as did the patient's maternal half-brother (his only sibling). The mother's medical history was remarkable for multiple first-trimester spontaneous abortions. The maternal grandmother had no evidence of porphyria, but she was chronically anemic (Hb level, 11.5 g/L) and thrombocytopenic (platelet count, 98 × 106/L). Her physicians had sought a cause for the cytopenias without success, and she had been observed without further intervention. Her blood smear revealed both normal-appearing red cells and a population of hypochromic, stippled cells and target cells. The red cell distribution width was increased at 19.5%. Platelets, although reduced in number, were morphologically normal. Her hemoglobin electrophoresis revealed a moderately elevated Hb F concentration of 4.8% but was otherwise normal.

Erythrocyte UROS activity was normal in both parents, an unexpected finding as obligate carriers (heterozygotes) for UROS mutations generally have half-normal enzymatic activity.11 UROS was sequenced, and no mutations or deletions were found in the child or the parents. Sequencing of the α- and β-globin loci (including the promoter regions) and Southern blotting of the α-globin cluster and the γ-globin genes also revealed no mutations or rearrangements. A proximal promoter polymorphism (−158 C/T) was identified in one allele of the Gγ-globin gene of the proband, both of his parents, and his maternal grandmother. This polymorphism, designated the XmnI polymorphism, has been associated with increased transcription of the Gγ allele and variable but modest elevations in Hb F levels, typically less than 5%.12 Globin chain analysis by denaturing Hb electrophoresis of the child's blood revealed a Gγ/Aγ ratio of 2:1, an increase over the “adult” 2:3 ratio expected by the age of 3 years.7

Globin labeling studies were done on mononuclear fractions of frozen marrow aspirates because reticulocytes from the child were not available. Bone marrow cells obtained from a healthy marrow donor expanded and differentiated as erythroblasts. In contrast, bone marrow cells obtained from the GATA-1 mutant child expanded less well, and the red cells appeared poorly hemoglobinized. The control culture incorporated 3H-lecuine (62545 cpm) into α, β, and γ chains with a ratio of α/β + γ of approximately 1. In contrast, the culture from the child incorporated 6105 cpm with a ratio of α/β + γ that was 2.1, a finding compatible with a β-thalassemia phenotype. The relative amounts of β and γ chain synthesis did not mirror the findings in the child's erythrocytes because β chain synthesis exceeded γ chain synthesis by approximately 3-fold.

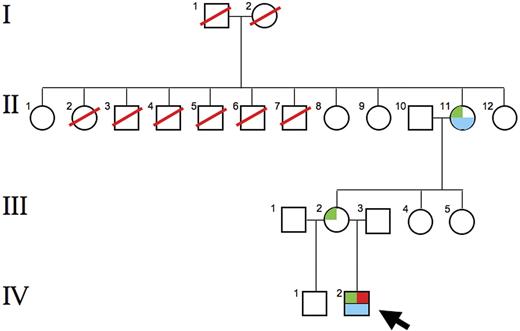

Lack of a molecular explanation for either the low UROS activity or the thalassemia/thrombocytopenia phenotype led us to suspect a trans-acting mutation, possibly X-linked. After excluding mutations in ATRX, an X-linked trans-acting chromatin remodeling factor associated with α-thalassemia, we sequenced GATA1. This gene, at Xp11.23, encodes a transcription factor, GATA binding factor 1 (GATA-1), that is critical for normal erythropoiesis, globin gene expression, and megakaryocyte development.13 GATA-1 also regulates expression of UROS in developing erythrocytes.8 A GATA1 point mutation was found in the child at codon 216, changing arginine to tryptophan (R216W), as well as on 1 of the 2 GATA1 alleles of his mother and maternal grandmother (Figure 3).

The UROS gene contains a housekeeping promoter 5′ to exon 1. The ATG start site is encoded in exon 2. There are 5 potential GATA-1 binding sites in the erythroid-specific promoter, located between exons 1 and 2, of the human UROS gene.8 We found no mutations at any of these sites. This arrangement yields different transcripts in erythroid and nonerythroid cells, but both initiate translation at the same initiation codon, yielding identical UROS proteins.8 The genes encoding ALA-D and PBG-D also contain erythroid-specific promoters that bind GATA-1. We found erythrocyte ALA-D activity in our case to be 48% of control values. In contrast, PBG-D activity was higher than normal at 168%. The URO-D gene does not contain a GATA-1–binding site, and URO-D activity was also increased at 174% of normal. The activities of ALA-D, PBG-D, and URO-D were normal in both parents.

Pedigree of the proband. The R216W GATA1 mutation was found in the proband (IV-2; ←), his mother (III-2), and his maternal grandmother (II-11). Marked anemia and 60% Hb F were found in the proband; a moderate anemia and 4.8% Hb F were found in the grandmother. Both the proband and his grandmother were thrombocytopenic. The grandmother was 1 of 11 siblings, including 5 brothers, and none were known to be anemic. Siblings II-8, II-9, and II-12 collectively had 7 sons (not shown). None were known to be anemic, and none had signs or symptoms of CEP. These findings suggest that the R216W mutation is a new mutation arising in the maternal grandmother. Green box indicates R216W GATA1 mutation; red box, porphyric phenotype; blue box, anemia, thrombocytopenia and high Hb F levels.

Pedigree of the proband. The R216W GATA1 mutation was found in the proband (IV-2; ←), his mother (III-2), and his maternal grandmother (II-11). Marked anemia and 60% Hb F were found in the proband; a moderate anemia and 4.8% Hb F were found in the grandmother. Both the proband and his grandmother were thrombocytopenic. The grandmother was 1 of 11 siblings, including 5 brothers, and none were known to be anemic. Siblings II-8, II-9, and II-12 collectively had 7 sons (not shown). None were known to be anemic, and none had signs or symptoms of CEP. These findings suggest that the R216W mutation is a new mutation arising in the maternal grandmother. Green box indicates R216W GATA1 mutation; red box, porphyric phenotype; blue box, anemia, thrombocytopenia and high Hb F levels.

The boy underwent an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation from an unrelated HLA-matched donor. Blood counts and porphyrin levels after the procedure became normal, his growth rate improved, and he remains well 2 years later.

Discussion

Mutations in several genes encoding transcription factors (eg, ATRX, TFIIH, and GATA1) have proven causative in rare cases of thalassemia.14 The present case represents the first description of a trans-acting mutation associated with CEP, and the first association of CEP with a collective hematologic phenotype of β-thalassemia intermedia, markedly elevated Hb F levels, and thrombocytopenia.

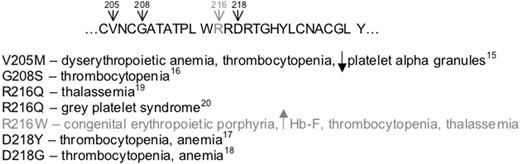

The R216 residue is located in a region of the N-terminal zinc finger of the GATA-1 protein that is highly conserved.15 Five germ line mutations of GATA1 causing X-linked disorders have been described, and all cluster in the N-terminal zinc finger. All are associated with altered affinity of GATA-1 for either its cofactor, Friend of GATA-1 (FOG1), or with palindromic DNA GATA recognition sites.15 These mutations and the associated phenotypes16–21 are shown in Figure 4. The thalassemia phenotype associated with the R216Q mutation differed dramatically from the phenotype in our case. The anemia was mild or absent, MCV values were normal, and Hb F levels ranged from 2.5% to 3.3%.22

Human GATA-1, residues 204-231, of the highly conserved DNA binding N-terminal zinc finger. The numbered residues indicate the locations of mutations that have been described. The mutations and their associated phenotypes are listed below the sequence. The mutation described here is shown in gray.

Human GATA-1, residues 204-231, of the highly conserved DNA binding N-terminal zinc finger. The numbered residues indicate the locations of mutations that have been described. The mutations and their associated phenotypes are listed below the sequence. The mutation described here is shown in gray.

The N-terminal zinc finger of the GATA-1 protein is important for stabilizing the binding of GATA-1 to palindromic WGATAR sites in the promoter elements of various genes important for erythropoiesis and megakaryopoiesis,20 including GATA1 itself.23 All patients in the pedigree with the R216Q mutation had less than 5% Hb F.22 The R216Q mutation permits normal GATA-1 binding to FOG1 as well as normal association with simple GATA DNA recognition sites, but it is associated with reduced binding affinity for palindromic GATA sites.20 There are 2 conserved GATA sites in the erythroid promoter regions of human and mouse UROS but only one is palindromic, −99 to −104 in the human.24 A more severe disruption of the N-terminal zinc finger is predicted with the insertion of the larger, more hydrophobic tryptophan described here which is predicted to dramatically affect binding to the −99 to −104 site. An erythroid promoter mutation in the nonpalindromic GATA site that prevented binding of GATA-1 has been reported in a patient with CEP.24 Collectively, these data indicate that both cis- and trans-acting mutations affecting GATA-1 binding can alter UROS expression.24 None of the previously reported GATA1 mutations resulted in porphyria or were associated with elevation of Hb F to the degree observed here. Somatic GATA1 mutations associated with acute megakaryoblastic leukemia and transient myeloproliferative disorder found in some patients with Down syndrome result in loss of the GATA-1 N-terminal activation domain but do not alter the N-terminal zinc finger or the transcription factor's DNA/FOG1 binding potential.15

We found moderately decreased ALA-D activity in our proband and increased activity of PBG-D. Activity of URO-D, an enzyme not regulated by GATA-1, was also increased. The increased activity of both PBG-D and URO-D is likely due to the young population of erythrocytes associated with the hemolytic anemia. Although GATA sites (including palindromic sites) are present in the regulatory elements of ALA-D and PBG-D, our observations suggest that UROS expression is particularly dependent on the stable binding of GATA-1 and its cofactors to palindromic GATA sites.

The elevated level of Hb F in this case is striking and is out of proportion to that described previously with GATA1 mutations. The XmnI G-γ polymorphism may play a minor role, but its association with normal Hb F levels in the boys' parents and the Hb F of 4.8% in the maternal grandmother suggest that it alone cannot be responsible for the 59.5% Hb F seen in the patient. Even when the XmnI polymorphism is associated with conditions of stressed erythropoiesis, such as homozygous Hb S, Hb F levels are usually less than 10% and always less than 20%.25 The attenuated hematologic phenotype in the grandmother is due to differential lyonization with the presence of both normal and mutant hematopoietic stem cell clones. The elevated Hb F level in our case suggests an important role for GATA-1 in normal globin chain switching during early development.

Globin chain labeling studies clearly defined the presence of a β-thalassemia phenotype in cultured mononuclear marrow cells, but γ chain synthesis did not reflect the findings in vivo. This is unexplained, but the cytokine-driven conditions used in the culture system might modulate the effects of mutant GATA-1.

This case demonstrates that CEP, in addition to thalassemia and thrombocytopenia, can also result from mutations in the trans-acting factor GATA-1. The marked effect of the R216W mutation on UROS among the GATA-1–dependent heme biosynthetic enzymes, as well as the marked elevation in Hb F associated with a fetal pattern of γ chain production, suggest that cis-elements vary in their affinity for GATA-1, and that distinct GATA1 mutations can result in diverse phenotypes.

Authorship

Contribution: J.D.P. and D.P.S. collected and analyzed data and prepared the manuscript; M.A.P. performed bone marrow transplantation; G.J.S. performed laboratory evaluation; J.P.K. performed clinical characterization, collected and analyzed data, prepared the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: John D. Phillips, Department of Medicine, University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, UT 84132; e-mail: john.phillips@hsc.utah.edu.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01DK020503, P30DK072437, and M01RR000064) (J.P.K.) and (K12CA90628) (D.P.S.).

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal