Abstract

The National Marrow Donor Program maintains a registry of volunteer donors for patients in need of a hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Strategies for selecting a partially HLA-mismatched donor vary when a full match cannot be identified. Some transplantation centers limit the selection of mismatched donors to those sharing mismatched antigens within HLA-A and HLA-B cross-reactive groups (CREGs). To assess whether an HLA mismatch within a CREG group (“minor”) may result in better outcome than a mismatch outside CREG groups (“major”), we analyzed validated outcomes data from 2709 bone marrow and peripheral blood stem cell transplantations. Three-hundred and ninety-six pairs (15%) were HLA-DRB1 allele matched but had an antigen-level mismatch at HLA-A or HLA-B. Univariate and multivariate analyses of engraftment, graft-versus-host disease, and survival showed that outcome is not significantly different between minor and major mismatches (P = .47, from the log-rank test for Kaplan-Meier survival). However, HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-DRB1 allele–matched cases had significantly better outcome than mismatched cases (P < .001). For patients without an HLA match, the selection of a CREG-compatible donor as tested does not improve outcome.

Introduction

HLA matching for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is currently based on antigen or allele identity between donor and recipient. Strategies for selecting a partially HLA-mismatched donor vary when a full match cannot be identified. Some of these strategies have been based on the theory that selection for HLA-A and HLA-B mismatches with antigenic similarity would evoke less allorecognition and immune activation and would constitute a permissive mismatch

The acronym HLA CREG (cross-reactive group) describes operationally monospecific HLA antisera that react with 2 or more HLA antigens (Table 1)1–3 This serologic cross-reactivity is now ascribed to determinants (public epitopes) that are differentially shared among HLA class I gene products. HLA-A and HLA-B gene products can be grouped into 8 or more families of CREG based upon serologic cross-reactivity patterns,1 associative analyses,4,5 or shared amino acid sequence polymorphisms.6 Potential donor and recipient pairs may be matched for public epitopes even though they are mismatched for the private epitopes that confer unique differences between class I HLA molecules. Thus, there are levels of immunologic matching of HLA gene products ranging from the allele level, in which all public and private epitopes are matched, to the CREG level, in which public epitopes are matched but private epitopes are mismatched.7

HLA class I serologically defined cross-reactive groups (CREGs) based on the Rodey scheme and example of the evaluation of minor versus major mismatches in a donor (HLA-A1,24, HLA-B8,35)-recipient (HLA-A1,28, HLA-B8,35) pair

| CREG* . | Antigen specificities included . | CREG present† . | CREG match status‡ . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor . | Recipient . | |||

| 1C | A1, 3, 9 (23, 24), 11, 29, 30, 31, 36, 80 | + | + | Match |

| 10C | A10 (25, 26, 34, 66), 11, 28 (68, 69), 32, 33, 43, 74 | − | + | Major mismatch in GvHD direction |

| 2C | A2, 9 (23, 24), 28 (68, 69), B17 (57, 58) | + | + | Match |

| 5C | B5 (51, 52), 15 (62, 63, 75, 76, 77), 17 (57, 58), 18, 21 (49, 50), 35, 46, 53, 70 (71, 72), 73, 78 | + | + | Match |

| 7C | B7, 8, 13, 22 (54, 55, 56), 27, 40 (60, 61), 41, 42, 47, 48, 59, 67, 81, 82 | + | + | Match |

| 8C | B8, 14 (64, 65), 16 (38, 39), 18, 59, 67 | + | + | Match |

| 12C | B12 (44, 45), 13, 21 (49, 50), 37, 40 (60, 61), 41, 47 | − | − | Match |

| Bw4 | A23, 24, 25, 32, B13, 27, 37, 38, 44, 47, 49, 51, 52, 53, 57, 58, 59, 63, 77 | + | − | Major mismatch in engraftment direction |

| Bw6 | B7, 8, 18, 35, 39, 41, 42, 45, 46, 48, 50, 54, 55, 56, 60, 61, 62, 64, 65, 67, 71, 72, 73, 75, 76, 78, 81, 82 | + | + | Match |

| CREG* . | Antigen specificities included . | CREG present† . | CREG match status‡ . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor . | Recipient . | |||

| 1C | A1, 3, 9 (23, 24), 11, 29, 30, 31, 36, 80 | + | + | Match |

| 10C | A10 (25, 26, 34, 66), 11, 28 (68, 69), 32, 33, 43, 74 | − | + | Major mismatch in GvHD direction |

| 2C | A2, 9 (23, 24), 28 (68, 69), B17 (57, 58) | + | + | Match |

| 5C | B5 (51, 52), 15 (62, 63, 75, 76, 77), 17 (57, 58), 18, 21 (49, 50), 35, 46, 53, 70 (71, 72), 73, 78 | + | + | Match |

| 7C | B7, 8, 13, 22 (54, 55, 56), 27, 40 (60, 61), 41, 42, 47, 48, 59, 67, 81, 82 | + | + | Match |

| 8C | B8, 14 (64, 65), 16 (38, 39), 18, 59, 67 | + | + | Match |

| 12C | B12 (44, 45), 13, 21 (49, 50), 37, 40 (60, 61), 41, 47 | − | − | Match |

| Bw4 | A23, 24, 25, 32, B13, 27, 37, 38, 44, 47, 49, 51, 52, 53, 57, 58, 59, 63, 77 | + | − | Major mismatch in engraftment direction |

| Bw6 | B7, 8, 18, 35, 39, 41, 42, 45, 46, 48, 50, 54, 55, 56, 60, 61, 62, 64, 65, 67, 71, 72, 73, 75, 76, 78, 81, 82 | + | + | Match |

Based on the HLA typing of the donor and recipient in the table title, these columns indicate whether the 9 CREG groups shown in the first column are present (+) or absent (−) in the donor or recipient.

In the United States, CREG matching has been introduced as a possible approach to increase the opportunity of a renal recipient to receive a “well-matched” kidney8 and to reduce the number of transplant rejections.9 This strategy is controversial, however, since European multicenter studies and a single US center study report no beneficial effect of CREG matching.10–13 It is unclear whether similar results may hold in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation because of the different set of risks involved (eg, graft-versus-host disease and disease relapse).

Studies of the influence of CREG in bone marrow transplantation are very limited. Studies of partially matched donors suggest that some degree of HLA mismatch may be tolerated.14,15 A single study from the University of Minnesota examined differences between mismatches within or outside of CREG groups and did not find differences in outcome,16 but the power was limited by small numbers. Based on the theoretical distinctions previously discussed, some transplantation centers have accepted a mismatch within a CREG while rejecting those with mismatches outside of a CREG, or have prioritized a mismatch within a CREG over a mismatch outside of a CREG. This study was designed to test the hypothesis that mismatched HLA-A or HLA-B antigens within a CREG group (“minor”) lead to a better transplantation outcome than mismatched antigens outside of the CREG groups (“major”) in hematopoietic stem cell transplant pairs matched for HLA-DRB1 alleles.

Patients, materials, and methods

Donor and recipient characteristics

This study included bone marrow and peripheral blood transplant pairs from 108 transplantation centers affiliated with the National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP) for which clinical outcome and retrospective high-resolution HLA typing data were available (n = 2709). All surviving recipients included in this analysis were retrospectively contacted and provided informed consent for participation in the NMDP research program, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was waived by the NMDP institutional review board for all deceased recipients. To address bias introduced by inclusion of only a proportion of surviving patients (those who consented) but all deceased recipients, a sample of deceased patients was selected using a weighted randomized scheme that adjusts for overrepresentation of deceased patients in the consented cohort. Patients underwent transplantation in centers using their local protocols for conditioning regimen and graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) prophylaxis. Most of the patients (2221; 82%) received total body irradiation with a median dose of 1320 cGy (range, 550-1800 cGy).

Recipient outcomes were reported to the NMDP Coordinating Center by the transplantation centers using standardized forms submitted at the time of transplantation (baseline), at 100 days, at 6 months, and annually thereafter. Computerized validation was used to check the data for consistency as it was entered into the database. Routine data audits of the transplantation centers were performed to ensure the information reported to NMDP was consistent with the medical records.

HLA assignments

At the time of the transplantation, donors and recipients were, at a minimum, typed serologically for HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-DR antigens. NMDP required that the transplantation centers resolve the assignments at the level of all well-defined subtypic specificities.17 Final donor selection was determined by each transplantation center based on its own criteria and on the minimum criterion established by the NMDP of a 5/6 antigen match at HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-DR. The donor and recipient HLA types were confirmed using pretransplantation blood samples collected by the NMDP and stored at the NMDP Research Sample Repository. All pairs were retrospectively high-resolution HLA typed for HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, and HLA-DRB1 using DNA sequencing and sequence-specific DNA probes.18,19 For comparison and analysis of CREG matching, the high-resolution HLA data were converted to serologic equivalents.20,21 The extents of allele matching for study populations are described in Tables 2–3.

Demographics of the study population (n = 2709)

| Characteristic . | Total . | A,B matched* . | Minor MM† . | Major MM† . | P‡ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease, no. (%) | .42 | ||||

| Chronic myelogenous leukemia | 1071 (40) | 933 (40) | 51 (38) | 87 (33) | |

| Chronic phase | 824 (30) | 723 (31) | 33 (24) | 68 (26) | |

| Accelerated phase | 187 (7) | 160 (7) | 12 (9) | 15 (6) | |

| Blast phase | 60 (2) | 50 (2) | 6 (4) | 4 (2) | |

| Acute myelogenous leukemia | 755 (28) | 640 (28) | 40 (29) | 75 (29) | |

| First CR | 170 (6) | 149 (6) | 8 (6) | 13 (5) | |

| Second CR | 214 (8) | 182 (8) | 17 (13) | 15 (6) | |

| Third or higher CR | 19 (1) | 17 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | |

| Relapse§ | 352 (13) | 292 (13) | 15 (11) | 45 (17) | |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 637 (24) | 523 (23) | 39 (29) | 75 (29) | |

| First CR | 161 (6) | 136 (6) | 13 (10) | 12 (5) | |

| Second CR | 224 (8) | 181 (8) | 9 (7) | 34 (13) | |

| Third or higher CR | 81 (3) | 62 (3) | 8 (6) | 11 (4) | |

| Relapse§ | 171 (6) | 144 (6) | 9 (7) | 18 (7) | |

| Myelodysplastic disorders | 246 (9) | 217 (9) | 6 (4) | 23 (9) | |

| Refractory anemia | 92 (3) | 82 (4) | 2 (1) | 8 (3) | |

| RAEB | 82 (3) | 75 (3) | 3 (2) | 4 (2) | |

| RAEBIT | 72 (3) | 60 (3) | 1 (1) | 11 (4) | |

| T-cell depletion, no. (%) | 528 (19) | 416 (18) | 36 (26) | 76 (29) | .56 |

| HLA-C match, no. (%) | |||||

| C allele match | 2011 (74) | 1835 (79) | 56 (41) | 120 (46) | .34 |

| C allele mismatch | 698 (26) | 478 (21) | 80 (59) | 140 (54) | |

| Cell sources, no. (%) | .79 | ||||

| Bone marrow | 2516 (93) | 2136 (93) | 131 (96) | 249 (96) | |

| Peripheral blood | 193 (7) | 177 (8) | 5 (4) | 11 (4) | |

| Karnofsky/Lansky score at transplantation,∥ no. (%) | .97 | ||||

| 90 to 100 | 1966 (73) | 1668 (72) | 101 (74) | 197 (76) | |

| 10 to 90 | 667 (25) | 575 (25) | 31 (23) | 61 (23) | |

| Unknown | 76 (3) | 70 (3) | 4 (3) | 2 (1) | |

| Recipient sex, no. (%) | .99 | ||||

| Female | 1180 (44) | 1008 (44) | 59 (43) | 113 (43) | |

| Male | 1529 (56) | 1305 (56) | 77 (57) | 147 (57) | |

| Donor/recipient CMV status at transplantation, no. (%) | .96 | ||||

| Negative/negative | 974 (36) | 845 (37) | 44 (32) | 85 (33) | |

| Negative/positive | 756 (28) | 647 (28) | 39 (29) | 70 (27) | |

| Positive/negative | 440 (16) | 370 (16) | 23 (17) | 47 (18) | |

| Positive/positive | 460 (17) | 386 (17) | 24 (18) | 50 (19) | |

| Unknown | 79 (3) | 65 (3) | 6 (4) | 8 (3) | |

| Racial or ethnic background, no. (%) | .46 | ||||

| White | 2479 (92) | 2151 (93) | 110 (81) | 218 (84) | |

| Other | 230 (8) | 162 (7) | 26 (19) | 42 (16) | |

| Year of transplantation, no. (%) | .51 | ||||

| 1988 to 1992 | 384 (14) | 303 (13) | 31 (23) | 50 (19) | |

| 1993 to 1995 | 547 (20) | 459 (20) | 33 (24) | 55 (21) | |

| 1996 to 1999 | 957 (35) | 837 (36) | 41 (30) | 79 (30) | |

| 2000 to 2003 | 821 (30) | 714 (31) | 31 (23) | 76 (29) | |

| Median recipient age, y (range) | 32 (< 1-65) | 32 (< 1-65) | 28 (< 1-55) | 27 (< 1-55) | .38 |

| Median donor age, y (range) | 36 (18-60) | 36 (18-60) | 35 (18-57) | 37 (19-59) | .16 |

| Median disease duration, mo (range)∥ | 20 (< 1-309) | 19 (< 1-309) | 24 (< 1-148) | 24 (1-161) | .47 |

| Characteristic . | Total . | A,B matched* . | Minor MM† . | Major MM† . | P‡ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease, no. (%) | .42 | ||||

| Chronic myelogenous leukemia | 1071 (40) | 933 (40) | 51 (38) | 87 (33) | |

| Chronic phase | 824 (30) | 723 (31) | 33 (24) | 68 (26) | |

| Accelerated phase | 187 (7) | 160 (7) | 12 (9) | 15 (6) | |

| Blast phase | 60 (2) | 50 (2) | 6 (4) | 4 (2) | |

| Acute myelogenous leukemia | 755 (28) | 640 (28) | 40 (29) | 75 (29) | |

| First CR | 170 (6) | 149 (6) | 8 (6) | 13 (5) | |

| Second CR | 214 (8) | 182 (8) | 17 (13) | 15 (6) | |

| Third or higher CR | 19 (1) | 17 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | |

| Relapse§ | 352 (13) | 292 (13) | 15 (11) | 45 (17) | |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 637 (24) | 523 (23) | 39 (29) | 75 (29) | |

| First CR | 161 (6) | 136 (6) | 13 (10) | 12 (5) | |

| Second CR | 224 (8) | 181 (8) | 9 (7) | 34 (13) | |

| Third or higher CR | 81 (3) | 62 (3) | 8 (6) | 11 (4) | |

| Relapse§ | 171 (6) | 144 (6) | 9 (7) | 18 (7) | |

| Myelodysplastic disorders | 246 (9) | 217 (9) | 6 (4) | 23 (9) | |

| Refractory anemia | 92 (3) | 82 (4) | 2 (1) | 8 (3) | |

| RAEB | 82 (3) | 75 (3) | 3 (2) | 4 (2) | |

| RAEBIT | 72 (3) | 60 (3) | 1 (1) | 11 (4) | |

| T-cell depletion, no. (%) | 528 (19) | 416 (18) | 36 (26) | 76 (29) | .56 |

| HLA-C match, no. (%) | |||||

| C allele match | 2011 (74) | 1835 (79) | 56 (41) | 120 (46) | .34 |

| C allele mismatch | 698 (26) | 478 (21) | 80 (59) | 140 (54) | |

| Cell sources, no. (%) | .79 | ||||

| Bone marrow | 2516 (93) | 2136 (93) | 131 (96) | 249 (96) | |

| Peripheral blood | 193 (7) | 177 (8) | 5 (4) | 11 (4) | |

| Karnofsky/Lansky score at transplantation,∥ no. (%) | .97 | ||||

| 90 to 100 | 1966 (73) | 1668 (72) | 101 (74) | 197 (76) | |

| 10 to 90 | 667 (25) | 575 (25) | 31 (23) | 61 (23) | |

| Unknown | 76 (3) | 70 (3) | 4 (3) | 2 (1) | |

| Recipient sex, no. (%) | .99 | ||||

| Female | 1180 (44) | 1008 (44) | 59 (43) | 113 (43) | |

| Male | 1529 (56) | 1305 (56) | 77 (57) | 147 (57) | |

| Donor/recipient CMV status at transplantation, no. (%) | .96 | ||||

| Negative/negative | 974 (36) | 845 (37) | 44 (32) | 85 (33) | |

| Negative/positive | 756 (28) | 647 (28) | 39 (29) | 70 (27) | |

| Positive/negative | 440 (16) | 370 (16) | 23 (17) | 47 (18) | |

| Positive/positive | 460 (17) | 386 (17) | 24 (18) | 50 (19) | |

| Unknown | 79 (3) | 65 (3) | 6 (4) | 8 (3) | |

| Racial or ethnic background, no. (%) | .46 | ||||

| White | 2479 (92) | 2151 (93) | 110 (81) | 218 (84) | |

| Other | 230 (8) | 162 (7) | 26 (19) | 42 (16) | |

| Year of transplantation, no. (%) | .51 | ||||

| 1988 to 1992 | 384 (14) | 303 (13) | 31 (23) | 50 (19) | |

| 1993 to 1995 | 547 (20) | 459 (20) | 33 (24) | 55 (21) | |

| 1996 to 1999 | 957 (35) | 837 (36) | 41 (30) | 79 (30) | |

| 2000 to 2003 | 821 (30) | 714 (31) | 31 (23) | 76 (29) | |

| Median recipient age, y (range) | 32 (< 1-65) | 32 (< 1-65) | 28 (< 1-55) | 27 (< 1-55) | .38 |

| Median donor age, y (range) | 36 (18-60) | 36 (18-60) | 35 (18-57) | 37 (19-59) | .16 |

| Median disease duration, mo (range)∥ | 20 (< 1-309) | 19 (< 1-309) | 24 (< 1-148) | 24 (1-161) | .47 |

CR indicates complete remission; RAEB, refractory anemia with excess blasts; RAEBIT, refractory anemia with excess blasts in transformation; and CMV, cytomegalovirus.

All pairs are matched for HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-DRB1 alleles.

Based on Rodey CREG scheme2,3 ; results were similar for Thompson et al22 and Takemoto6 CREG schemes. These transplants are mismatched for a single allele at HLA-A or HLA-B but matched for all other alleles at HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-DRB1.

P values comparing minor versus major mismatches using the chi-square statistic for discrete variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables.

Includes primary induction failures.

Diagnosis date missing in 11 cases.

HLA matching of donors and recipients

| . | Total, no. (%) . | HLA-C allele match, no. (%) . | HLA-C allele mismatch, no. (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-DRB1 allele matched | 2313 (85) | 1835 (91) | 478 (68) |

| Mismatch at HLA-A only* | 238 (9) | 161 (8) | 77 (11) |

| Mismatch at HLA-B only* | 158 (6) | 15 (1) | 143 (20) |

| . | Total, no. (%) . | HLA-C allele match, no. (%) . | HLA-C allele mismatch, no. (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-DRB1 allele matched | 2313 (85) | 1835 (91) | 478 (68) |

| Mismatch at HLA-A only* | 238 (9) | 161 (8) | 77 (11) |

| Mismatch at HLA-B only* | 158 (6) | 15 (1) | 143 (20) |

Mismatch is only one allele at named locus. All other key loci are matched.

CREG matching

Three published CREG schemes (Rodey et al2 and Rodey3 ; Takemoto6 ; and Thompson et al22) were used in the analyses. CREGs associated with the recipient and with the donor HLA-A and HLA-B antigens were evaluated by computerized algorithms. Cases in which a CREG was associated with a donor phenotype but was missing in a recipient were considered a major mismatch in the analysis of engraftment; whereas a CREG present in a recipient and not in a donor was considered a major mismatch in the GvHD analysis (Table 1). A mismatch in either direction was considered a major mismatch in the survival analysis. Approximately 85% of cases were HLA-A and HLA-B matched at allele level, and about 5% to 6% were classed as minor mismatches and 8% to 9% as major mismatches. The gamma statistic that measures association between the scores on a scale of 0 to 1 was larger than 0.99 for all pair-wise comparisons.

Statistical methods

Data from each transplantation were collected prospectively from each transplantation center on standardized forms. Data were validated by the NMDP for accuracy and consistency. Time to neutrophil engraftment was defined as the first day of 3 consecutive laboratory values at or above 0.5 × 109 cells/L. A severity grade was calculated for acute GvHD according to the reported stages of skin, liver, and intestinal involvement.23

Univariate analyses were performed on the HLA-matched and -mismatched pairs (Table 4). Survival rates were calculated by the method of Kaplan-Meier24 and compared using the log-rank statistic.25 Rates of engraftment and GvHD were calculated by cumulative incidence,26 treating death from any cause as a competing risk and censored at the date of second transplantation. Cumulative incidences were compared at a particular time point (28 days for engraftment, 100 days for acute GvHD, and 2 years for chronic GvHD) using a first-order Taylor series to estimate the variance.27

Univariate outcomes based on the Rodey classification

| Outcome . | Matched, % (range) . | Minor mismatch, % (range) . | Major mismatch, % (range) . | P* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall survival | ||||

| 1 y | 51 (48-53) | 37 (29-45) | 37 (32-43) | < .001 |

| 2 y | 43 (41-45) | 28 (21-35) | 31 (26-37) | < .001 |

| 5 y | 36 (34-38) | 21 (15-27) | 26 (21-32) | < .001 |

| Disease-free survival | ||||

| 1 y | 46 (43-48) | 29 (22-37) | 33 (27-39) | < .001 |

| 2 y | 39 (37-41) | 25 (18-32) | 27 (22-33) | < .001 |

| Death in remission | ||||

| 1 y | 37 (35-39) | 52 (44-61) | 53 (47-59) | < .001 |

| 2 y | 41 (39-43) | 56 (48-64) | 56 (50-62) | < .001 |

| Relapse | ||||

| 1 y | 17 (16-19) | 19 (13-26) | 14 (10-18) | .344 |

| 2 y | 20 (18-21) | 19 (13-27) | 16 (12-21) | .385 |

| Grade 2-4 acute GvHD | ||||

| 100 d | 50 (48-52) | 62 (55-59) | 54 (47-62) | .002 |

| Grade 3-4 acute GvHD | ||||

| 100 d | 30 (28-32) | 46 (39-52) | 41 (33-48) | < .001 |

| Chronic GvHD | ||||

| 2 y | 45 (43-47) | 39 (32-46) | 40 (32-48) | .124 |

| Engraftment | ||||

| 28 dn | 90 (88-91) | 85 (79-90) | 82 (76-88) | .027 |

| Outcome . | Matched, % (range) . | Minor mismatch, % (range) . | Major mismatch, % (range) . | P* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall survival | ||||

| 1 y | 51 (48-53) | 37 (29-45) | 37 (32-43) | < .001 |

| 2 y | 43 (41-45) | 28 (21-35) | 31 (26-37) | < .001 |

| 5 y | 36 (34-38) | 21 (15-27) | 26 (21-32) | < .001 |

| Disease-free survival | ||||

| 1 y | 46 (43-48) | 29 (22-37) | 33 (27-39) | < .001 |

| 2 y | 39 (37-41) | 25 (18-32) | 27 (22-33) | < .001 |

| Death in remission | ||||

| 1 y | 37 (35-39) | 52 (44-61) | 53 (47-59) | < .001 |

| 2 y | 41 (39-43) | 56 (48-64) | 56 (50-62) | < .001 |

| Relapse | ||||

| 1 y | 17 (16-19) | 19 (13-26) | 14 (10-18) | .344 |

| 2 y | 20 (18-21) | 19 (13-27) | 16 (12-21) | .385 |

| Grade 2-4 acute GvHD | ||||

| 100 d | 50 (48-52) | 62 (55-59) | 54 (47-62) | .002 |

| Grade 3-4 acute GvHD | ||||

| 100 d | 30 (28-32) | 46 (39-52) | 41 (33-48) | < .001 |

| Chronic GvHD | ||||

| 2 y | 45 (43-47) | 39 (32-46) | 40 (32-48) | .124 |

| Engraftment | ||||

| 28 dn | 90 (88-91) | 85 (79-90) | 82 (76-88) | .027 |

P values are the pointwise P values comparing 3 groups.

Multivariate analyses were performed using logistic regression for engraftment and the proportional hazards regression model28 for survival and GvHD. Each regression model was adjusted for diagnosis and HLA matching as categorized in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. HLA-A and HLA-B allele matching was treated as one risk factor with cases classified as a match, a minor mismatch, or a major mismatch. Additional risk factors were included in the regression model if the Wald chi-square statistic yielded a P value less than .05. Factors considered were HLA-C match, disease, disease status, cell sources, recipient and donor age, sex, CMV serology, race, interval from diagnosis to transplantation, T-cell depletion, total body irradiation, and year of transplantation. Adjustment for center-specific effects had no impact on the outcomes and was not included in the model.

For each outcome, separate regression models were run for each definition of CREG groups considered in this study. Due to nonlinear effects, the continuous variables—recipient age and interval from diagnosis to transplantation—were categorized into discrete groups. The effect of interval from diagnosis to transplantation was modeled separately for each diagnosis. All analyses were performed using the SAS statistical software (version 9.1; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Demographics and CREG matching

The demographics of the study population were stratified by minor versus major mismatches as defined by the Rodey CREG algorithm (Table 2). There were no differences between minor and major mismatches within any of the 3 CREG schemes.

HLA-A and HLA-B locus mismatches totaled 396 (Table 3). Minor mismatches at the HLA-A locus were 21%, 29%, and 26% of the total mismatches as defined according to the CREG models of Rodey et al2 and Rodey3 ; Takemoto6 ; and Thompson et al22 , respectively; minor mismatches at the HLA-B locus were 14%, 13%, and 11%, respectively. The analyses using the Rodey scheme are shown in this report. The results obtained with the other 2 classifications, Thompson et al22 and Takemoto,6 were similar (data not shown). Additionally, analyses were repeated on each outcome testing minor versus major separately in HLA-A and in HLA-B mismatches and no differences were detected (some data not shown). Because of the large number of comparisons involved, P values higher than .01 were not considered statistically significant.

Engraftment

There was no significant difference between minor and major mismatches for engraftment in univariate analysis (85% with 95% CI: 79%-90% vs 82% with 95% CI: 76%-88%). Engraftment was significantly better in HLA-A– and HLA-B–matched cases (90% with 95% CI: 88%-91%). Logistic regression found no significant effect of major mismatches compared with minor mismatches (P = .67).

Acute graft-versus-host disease

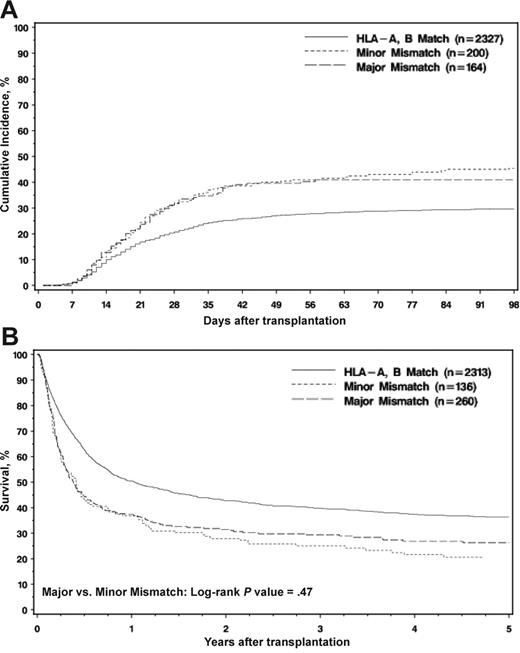

As shown in Figure 1A, the cumulative incidence curves of acute GvHD grades III to IV showed no significant difference between minor and major mismatches (46% with 95% CI: 39%-52% vs 41% with 95% CI: 33%-48%). Evaluation of grades II to IV (Table 4) showed similar results (62% with 95% CI: 55%-69% vs 54% with 95% CI: 47%-62%). HLA-A– and HLA-B–matched cases showed a significantly reduced incidence (grades III-IV: 30% with 95% CI: 28%-32%; grades II-IV: 50% with 95% CI: 48%-52%) (Table 4). A proportional hazards regression model of grades III to IV acute GvHD (Table 5). also showed no significant difference between minor and major mismatches (P = .44 and P = .78 for grades II-IV and III-IV, respectively).

Posttransplantation outcome in the HLA-DRB1 matched patients based on HLA-A and HLA-B match status. (A) Probability of developing grades III to IV acute GvHD. The log-rank test from Kaplan-Meier of major versus minor mismatch did not detect a significant difference (P = .474). (B) Kaplan-Meier survival of the DRB1-matched patients according to HLA-A and HLA-B match status. The log-rank test from Kaplan-Meier of major versus minor mismatch did not detect a significant difference (P = .469).

Posttransplantation outcome in the HLA-DRB1 matched patients based on HLA-A and HLA-B match status. (A) Probability of developing grades III to IV acute GvHD. The log-rank test from Kaplan-Meier of major versus minor mismatch did not detect a significant difference (P = .474). (B) Kaplan-Meier survival of the DRB1-matched patients according to HLA-A and HLA-B match status. The log-rank test from Kaplan-Meier of major versus minor mismatch did not detect a significant difference (P = .469).

Proportional hazards regression

| Factor . | RR . | 95% CI . | P . | Favorable . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grades III-IV acute GvHD* | ||||

| HLA-A, HLA-B allele match† | 1.00 | Reference | NA | NA |

| Minor mismatch | 1.52 | 1.21-1.91 | .001 | Match |

| Major mismatch | 1.45 | 1.21-1.91 | .005 | Match |

| HLA-C allele match | 1.00 | Reference | NA | NA |

| HLA-C single allele mismatch | 1.40 | 1.19-1.63 | < .001 | C allele match |

| Minor vs major | 1.04 | 0.76-1.43 | .784 | Neither |

| Overall survival‡ | ||||

| HLA-A, HLA-B allele match | 1.00 | Reference | NA | NA |

| Minor mismatch | 1.51 | 1.23-1.86 | < .001 | Match |

| Major mismatch | 1.40 | 1.19-1.64 | < .001 | Match |

| HLA-C allele match | 1.00 | Reference | NA | NA |

| HLA-C single allele mismatch | 1.25 | 1.12-1.40 | < .001 | C allele match |

| Minor vs major | 1.08 | 0.85-1.37 | .525 | Neither |

| Factor . | RR . | 95% CI . | P . | Favorable . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grades III-IV acute GvHD* | ||||

| HLA-A, HLA-B allele match† | 1.00 | Reference | NA | NA |

| Minor mismatch | 1.52 | 1.21-1.91 | .001 | Match |

| Major mismatch | 1.45 | 1.21-1.91 | .005 | Match |

| HLA-C allele match | 1.00 | Reference | NA | NA |

| HLA-C single allele mismatch | 1.40 | 1.19-1.63 | < .001 | C allele match |

| Minor vs major | 1.04 | 0.76-1.43 | .784 | Neither |

| Overall survival‡ | ||||

| HLA-A, HLA-B allele match | 1.00 | Reference | NA | NA |

| Minor mismatch | 1.51 | 1.23-1.86 | < .001 | Match |

| Major mismatch | 1.40 | 1.19-1.64 | < .001 | Match |

| HLA-C allele match | 1.00 | Reference | NA | NA |

| HLA-C single allele mismatch | 1.25 | 1.12-1.40 | < .001 | C allele match |

| Minor vs major | 1.08 | 0.85-1.37 | .525 | Neither |

NA indicates not applicable.

Acute GvHD model was stratified on disease, T depletion, and year of transplantation. It was adjusted for radiation in the conditioning regimen (P = .311) and cell source (P ≤ .001).

No significant interaction was detected between HLA-C and CREG matching (grades III-IV GvHD, P = .53; overall survival, P = .25).

Overall survival model was stratified on patient age and sex match. It was adjusted for race (P = .002), donor-patient CMV status (P < .001), Karnofsky/Lansky score at transplantation (P < .001), disease (P < .001), and disease stage (P < .001).

Chronic GvHD

There was no difference between minor and major mismatches for chronic GvHD in univariate analysis (39% with 95% CI: 32%-46% vs 40% with 95% CI: 32%-48%) (Table 4). A proportional hazards regression also showed no significant effect of major mismatches compared with minor mismatches (P = .44).

Survival

Five-year overall survival was significantly better in HLA-A– and HLA-B–matched cases (36% with 95% CI: 34%-38%), but there were no significant differences between minor and major mismatches (21% with 95% CI: 15%-27% vs 26% with 95% CI: 21%-32%) as shown in Table 4 and Figure 1B. These results were confirmed in a multivariate regression model (Table 5). There were no detectable differences in 5-year overall survival between minor or major among HLA-A mismatches (22% with 95% CI: 15%-31% vs 30% with 95% CI: 23%-37%) or HLA-B mismatches (18% with 95% CI: 10%-27% vs 21% with 95% CI: 14%-29%). There were no significant differences between minor and major mismatches in the reported primary or secondary causes of death.

T-cell depletion

T-cell depletion has been used to reduce GvHD occurring as a consequence of HLA mismatching.29 In the multivariate analyses, an interaction between T depletion and CREG was tested where appropriate (engraftment, GvHD); no significant effect was found (P = .2 for engraftment; P = .15 for both acute and chronic GvHD).

Analysis of CML group

When the analyses were restricted to the 1071 chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) cases comprising the largest disease group (40%), results were similar to the analyses of the entire dataset. HLA-A and HLA-B matches had significantly better outcome than mismatches, but there were no detectable differences between minor and major mismatches regardless of which definition of CREG was used. Five-year overall survival rates were 44% (95% CI: 41%-47%), 25% (95% CI: 15%-37%), and 31% (95% CI: 22%-41%) for HLA-A and HLA-B matches; minor mismatches; and major mismatches, respectively.

Impact of HLA-C

Matching for alleles of HLA-C is known to impact outcome.19,30–32 In the present study, the patients matched for HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, and HLA-DRB1 alleles showed significantly improved outcomes compared with HLA-C–mismatched cases (grades III-IV GvHD, P < .001; overall survival, P < .001) (Table 5). However, no significant interaction was detected between HLA-C and CREG matching in any of the test groups (grades III-IV GvHD, P = .53; overall survival, P = .25).

Discussion

Our analyses of a validated database from 2709 cases registered with the NMDP confirm the significantly improved outcome in recipients receiving a bone marrow and peripheral blood stem cell transplant from an HLA-matched donor. Mismatching for a single HLA-A or HLA-B serologic determinant significantly decreases the outcome. However, when either an HLA-A or HLA-B mismatch was present between donor and recipient, matching for the shared determinants as defined by any of the 3 published CREG schemes2,3,6,22 did not significantly improve the outcomes. This multicenter study confirms and extends the findings reported by a single center.16

While this study confirms the impact of HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-DRB1 matching on transplantation outcome observed by others,16,19,33 the focus of this analyses was directed toward the development of permissive HLA-mismatching criteria for those patients without matched donors. One study of unrelated transplants for CML did not identify a significant effect of minor HLA-A and HLA-B antigen mismatching on transplantation outcome, but statistical power was limited because only 24 of the 196 pairs analyzed had such a mismatch.34 Donors selected on the basis of characteristics of the mismatched serologic HLA-A and HLA-B antigens, specifically whether the mismatches were assigned to the same CREG clusters (minor) or to different CREG clusters (major), were evaluated, and the CREG status of the mismatch was found to have no impact on the transplantation outcome in the recipient. Since disparity at the multiple HLA loci undetected by serologic typing has been shown to affect graft function, the similarity in outcome between minor compared with major mismatches predicts that both mismatched groups will exhibit similar levels and characteristics of overall HLA allele disparity. A project to retrospectively identify the alleles of all HLA loci in transplant pairs facilitated through the NMDP will also contribute to the evaluation of other permissive mismatching schemes based on structural and functional homology.

The influence of CREG on the immune response to an allograft is unclear. Studies in the mouse suggest that cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) are generated in vitro35,36 and that skin graft rejection can be induced37 to “public” determinants. In humans, both the presence of an antibody response2,38 and of CTLs directed to CREG determinants39 have been documented; however, CTL precursor frequencies in humans have been shown to correlate with HLA but not with CREG mismatches.40 Analysis of the transplantation outcomes in this clinical study did not detect a difference in mismatches within or outside a CREG and provides no evidence to support a reduction in the allorecognition or immune activation attributable to these shared determinants following bone marrow transplantation.

Despite the growth and diversification of volunteer registries worldwide, a significant number of patients are still unable to find an HLA-matched donor. In these patients, the choice of a single HLA-A or HLA-B mismatch need not be restricted to a mismatch within a CREG, providing a larger acceptable pool of donors for patients without a perfect match. This larger pool offers the opportunity to select for other desirable donor characteristics, such as a younger donor, to mitigate the deleterious effect of a single HLA-antigen mismatch.41

These data emphasize the need to develop strategies that will improve the outcome of HLA-mismatched transplantations. Approaches to reduce the severity of allorecognition might include depletion of T lymphocytes,29 selection of a “naive” stem cell source (eg, umbilical cord blood42,43 ), development of minimal conditioning regimens, and identification of permissive HLA mismatches. This study clearly demonstrates that the CREG determinants as defined do not form the basis for a permissive matching scheme for bone marrow and peripheral blood transplantation.

Authorship

Contribution: J.A.W., C.K.H., S.K.T., J.T., S.M.D., T.C.F., G.R., D.L.C., H.N., J.K., and C.K. participated in the design of the study; J.A.W., C.K.H., S.K.T., J.T., T.C.F., G.R., H.N., and S.S. assigned and reviewed the CREGs; M.H., F.K., J.K., M.E., and C.K. performed the statistical analysis; J.A.W., C.K.H., S.S., and C.K. wrote the paper; and all authors reviewed the analysis and checked the final version of the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Stephen Spellman, 3001 Broadway St NE, Minneapolis, MN 55413; e-mail: sspellma@nmdp.org.

Presented in abstract form at the American Society for Bone Marrow Transplantation meeting, Keystone, CO, February 18, 2001 (M. M. Bortin award).44

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Marrow Donor Program in part through funding from the Health Resources and Services Administration (no. 240-97-0036) and the Office of Naval Research (N00014-96-2-0016, N00014-99-2-0006, and N00014-5-1-0859). Other funding support included NIH DK54928-01 (S.T.) and ONR N00014-99-1-0051 (C.K.H.).

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or the US government. We would like to acknowledge the efforts of the NMDP Transplant and Donor Centers in providing data for this study, the NMDP contract laboratories for performing high-resolution HLA testing, and the NMDP staff for their assistance.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal