How platelets are produced has been a long-lasting and controversial story. In culture, mature megakaryocytes (MKs) produce long, almost string-like proplatelets that bud off large numbers of platelets from their ends.1 Organelles are conveyed along tubulin-dependent tracks to the forming platelets. But, culture conditions do not mimic the bone marrow environment where MKs mature in the presence of positive and negative regulators influencing both cell growth and differentiation. MKs must also migrate to the endothelial layer delimiting the sinusoidal vasculature, into which they extrude their proplatelets. So, how are these steps controlled? The fact that defects in GPIBA encoding the GPIbα adhesion receptor, or in MYH9 encoding the myosin-IIA motor, both give rise to congenital macrothrombocytopenias suggests a role for the GPIb-cytoskeletal axis during megakaryocytopoiesis.2

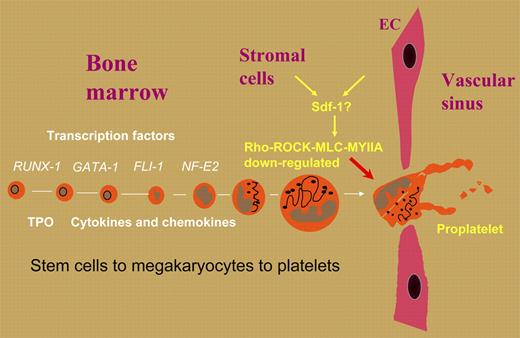

In this issue of Blood, Chen and colleagues have looked at the role of MYH9 in thrombocytopoiesis, and show how myosin-IIA complexes and their upstream signaling pathways regulate the timing of proplatelet formation. The latter was enhanced in MKs derived from Myh9–/– embryonic stem cells, while raised expression of myosin-IIA activity or constitutive phosphorylation of regulatory myosin light chain (MLC) led to significantly reduced proplatelet formation. As MLC phosphorylation in MKs is controlled by Rho-associated kinase (ROCK), ROCK inhibition was first hypothesized and then shown to enhance proplatelet formation. Significantly, hematopoietic transplant studies in mice confirmed that interference with this pathway resulted in decreased numbers of circulating platelets. These studies nicely supplement and extend findings in a recent issue of Blood from a study by Chang et al,3 who showed that proplatelet formation under culture conditions was negatively regulated by the Rho-ROCK pathway. In vivo, this could mean that a lifting of the restraints imposed on proplatelet formation by the Rho-ROCK-MLC-myosinIIA pathway is the key trigger for proplatelet formation at the sinusoids. A candidate here is stromal-cell–derived factor (Sdf-1 or CXCL12), a known chemoattractant that dampens Rho activity. The role of these pathways is summarized in the figure.

Positive and negative regulators in the bone marrow may determine the time and place of proplatelet formation in mature megakaryocytes and strategically control platelet production.

Positive and negative regulators in the bone marrow may determine the time and place of proplatelet formation in mature megakaryocytes and strategically control platelet production.

How does this work translate to the autosomal-dominant, MYH9-related disorders? The work of Chen and colleagues suggests that in the May-Hegglin anomaly, platelets are produced prematurely, perhaps from immature MKs. A similar suggestion was recently hypothesized to explain giant platelets in a patient with type 2B von Willebrand disease.4 Does GPIb signal similarly? Nonetheless, in the May-Hegglin anomaly, macrothrombocytopenia is associated with inclusions in the Döhle bodies of neutrophils; in the Epstein and Fechtner syndromes, however, patients can variably suffer from deafness, kidney disease, and cataracts. MYH9-related effects extend to other cell types with distinct patient heterogeneity, perhaps reflecting other modulator genes or epigenetic control, mechanisms that remain to be identified. Perhaps the MYH9-related diseases are not monogenic after all. Not in the least, the work of Chen and colleagues implies that familial thrombocytopenias could result from inherited defects in stromal cells as well as in MKs.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal