Late mortality after allogeneic hematopoetic cell transplantation remains twice as high as that of the general population, and functional well-being is poorer among 15-year survivors.

Allogeneic hematopoetic cell transplantation (HCT) offers a curative approach for a number of malignant and nonmalignant diseases.1 The price of this treatment is high early non–relapse-related mortality. Nevertheless, long-term prognosis has greatly improved. Because immediate survival is no longer the sole concern, long-term health status and the development of late events related to HCT have gained increasing interest.2,3 Today, many late events, such as secondary malignancies, late infections, pulmonary complications, endocrinal dysfunction, and cardiovascular events have been well described. However, for long-term outcome, there are still a limited number of studies.

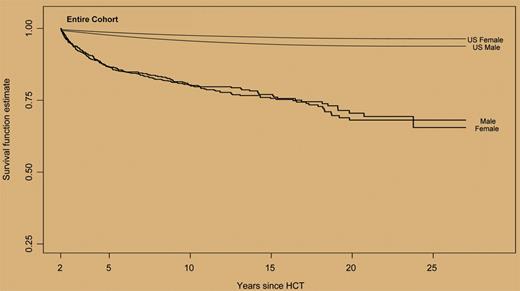

In this issue of Blood, Bhatia and colleagues undertook a comprehensive analysis of late mortality in individuals who had survived 2 years or more after allogeneic HCT, and of functional status in a subgroup of these patients. At 10 years, more than 80% of the patients were alive, and for patients without chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), the survival rate was more than 90%. Of the 1479 patients who received transplants between 1974 and 1998, 320 had died. The relative risk was increased in all groups and at any time since transplantation. It was highest in the 2- to 5-year period (78 fold), intermediate in the 6- to 10-year period (8 fold), and remained twice as high in patients surviving 15 years or more. Relapse of primary disease was the cause of death in 29% of the patients. Non–relapse-related causes of death were chronic GVHD (22%), late infections without GVHD (11%), secondary malignancies (7%), pulmonary complications (5%), and cardiac complications (3%). Higher risk of mortality was associated with increased age at transplantation, the presence of chronic GVHD, and advanced disease stage. In the second part of the study, the functional well-being, including marital state, employment, and possession of health/life insurance, was evaluated in a subgroup of 547 patients. As compared with 319 sibling donors, well-being was decreased for all parameters: fewer long-term survivors were currently married, and they had more difficulty holding jobs and obtaining health/life insurance.

These results are of great importance because they demonstrate that late mortality is increased even in very long-term HCT survivors, and that well-being is still not comparable to a matched control group. The authors should be congratulated for the huge amount of comprehensive data provided, particularly in the different tables. They present useful results on late mortality in all subgroups of patients, and analyze the outcome separately according to disease-related and non–disease-related mortality. This split investigation is required to compare the results of HCT to other types of treatment, given that the excess of death in transplantation is mainly due to non–disease-related mortality.

All-cause mortality in a cohort of 1479 2+-year survivors after allogeneic HCT. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 3784.

All-cause mortality in a cohort of 1479 2+-year survivors after allogeneic HCT. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 3784.

Overall, the results of this study cannot been neglected. Despite the fact that HCT is considered the only curative treatment option for a number of diseases, patients face an excessive risk of dying even when their primary disease is in remission. The good news delivered by these results is that we now have a fairly good estimate on the risk of late mortality. This knowledge is essential for optimizing management of late events after HCT.4 Moreover, it permits us to define the best treatment option at diagnosis, and to identify more accurately patients who are likely to benefit from HCT. Considering that risk scores have been established with success for transplantation, and are currently in use for decision making, the results of this study give us the tools for including long-term outcome and late mortality in such risk scores.

Finally, these results clearly demonstrate that individuals undergoing allogeneic HCT, even when cured, will never become nonpatients. Allogeneic HCT is a lifelong commitment for all—the patient, his or her family, the primary care physician, the transplantation team, and the healthcare providers—and structures have to be created to assure long-term follow-up with survivors after HCT.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal