Tumor growth induced a significant increase of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) in the tumor-bearing host. In our previous study, we showed that MDSCs induced tumor-specific T-cell tolerance and the development of T regulatory cells (Tregs). Tumor-derived factors have been implicated in the accumulation of MDSCs. We hypothesize that reduction of MDSC accumulation in tumor-bearing hosts, through the blockade of tumor factors, can prevent T-cell anergy and Treg development and thereby improve immune therapy for the treatment of advanced tumors. Several tumor-derived factors were identified by gene array analysis. Among the candidate factors, stem- cell factor (SCF) is expressed by various human and murine carcinomas and was selected for further study. Mice bearing tumor cells with SCF siRNA knockdown exhibited significantly reduced MDSC expansion and restored proliferative responses of tumor-infiltrating T cells. More importantly, blockade of SCF receptor (ckit)–SCF interaction by anti-ckit prevented tumor-specific T-cell anergy, Treg development, and tumor angiogenesis. Furthermore, the prevention of MDSC accumulation in conjunction with immune activation therapy showed synergistic therapeutic effect when treating mice bearing large tumors. This information supports the notion that modulation of MDSC development may be required to achieve effective immune-enhancing therapy for the treatment of advanced tumors.

Introduction

Immune-based therapy has achieved a certain level of success; however, the overall therapeutic effect has been much less promising due to the immune suppressive mechanisms associated with advanced malignancies.1 To achieve a better therapeutic efficacy of immune activation therapy, the mechanism or mechanisms by which a large tumor burden prevents immune activation from inducing effective antitumor immunity needs to be elucidated.

Tumor growth is accompanied by an increase in the number of Gr-1+Mac-1+ myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)2,–4 and tumor-specific T regulatory cells (Tregs)5,6 with strong immune suppressive activity in cancer patients and in tumor-bearing mice.7,–9 Both MDSCs and Tregs may be directly involved in immune unresponsiveness in active immune therapy.

It has been demonstrated that MDSCs are involved in T-cell hyporesponsiveness in tumor-bearing mice. Several mechanisms by which MDSCs regulate the tumor-specific T-cell response have recently been proposed and the in vivo immune regulatory effects of MDSCs on tumor-specific T-cell response have been identified.7,,,,–12 T-cell inactivation can be mediated by MDSCs through IFNγ-dependent nitric oxide (NO) production12,,,–16 or the Th2-mediated IL-4/IL-13–dependent arginase 1 pathway.14,17,,,,–22 In addition, a mechanism of ROS-mediated cell killing has been proposed.3,23,24 Furthermore, MDSCs can inhibit cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses through NO-dependent or -independent mechanisms. Cell-to-cell contact appeared to be crucial in these mechanisms.25 Our laboratory has further identified a novel mechanism of MDSC-mediated immune suppression on activated T cells through the development of Foxp3+ T regulatory cells (Tregs) and T-cell tolerance both in vitro and in tumor-bearing mice. The induction of Tregs by MDSCs requires IFN-γ and IL-10 but is independent of the NO-mediated suppressive mechanism.11 To overcome MDSC-mediated immune suppression and prevent Treg induction, it is critical to identify the tumor factors that are required for MDSC accumulation in tumor-bearing animals.

Several lines of evidence support the hypothesis that the development and expansion of MDSCs may be modulated by tumor-secreted factors. MDSCs in tumor-bearing animals can differentiate into mature dendritic cells or remain as MDSCs with inhibitory activities, depending on the local cytokine milieu.26,27 Human renal cell carcinoma cell lines release soluble factors (IL-6, M-CSF) that inhibit the differentiation of CD34+ cells into dendritic cells (DCs) and trigger their commitment toward monocytic cells.28 In a transgenic mammary tumor, VEGF levels correlate with the MDSC number.29 Moreover, the in vivo infusion of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) can induce MDSC development in naive mice and impair DC function and differentiation.30 Granulocyte macrophage–colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) secretion has correlated with the capacity of tumor metastases and the GM-CSF and IL-3 in conditioned medium from Lewis lung carcinoma may induce MDSCs from bone marrow culture.31 The concentration of GM-CSF plays a critical role in the balancing act between immune suppression by MDSCs and immune activation by mature dendritic cells.7 Additional evidence suggests that many cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), GM-CSF, interferon γ (IFN-γ), IL-6, IL-4, VEGF, transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), IL-10, and Flt3 ligand are likely to be involved in the differentiation of myeloid progenitors present in blood, bone marrow, and spleen.27,30,32,,–35 However, which tumor-associated factors are critical for MDSC accumulation, how tumor factors affect MDSC development and the tumor-specific immune response, and whether control of MDSC expansion may facilitate immune-based therapy have not been fully evaluated.

Here, we identified that stem cell factor (SCF, ckit ligand, steel factor) is expressed by multiple human and murine tumor cell lines and is a vital factor for MDSC accumulation associated with advanced malignancy. We postulate that an abnormal level of SCF caused by a large tumor burden can lead to an increase in myelopoiesis and a decrease in monocyte/granulocyte/DC differentiation, thereby resulting in MDSC expansion, and that blockade of MDSC accumulation in tumor-bearing mice may facilitate a more effective immune-enhancing therapy in the treatment of advanced tumors.

Methods

Experimental animal and tumor models

The MCA26 tumor cell line is a BALB/c-derived, chemically induced colon carcinoma line with low immunogenicity.36 The SCF knockdown clones were generated by stable transfection of MCA26 with pSIREN-Shuttle vector (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA) expressing SCF shRNA (sense CAGTCAAGTCTTACAAGGG and antisense CCCTTGTAAGACTTGACTG) and puromycin selection (4 μg/mL). Multiple stable SCF knockdown clones were selected for further analysis and study. To establish a model in which tumor antigen-specific T-cell responses can be tracked in vivo, the MCA26 colon tumor cell line that express influenza hemagglutinin (HA), HA-MCA26, was established.11

Congenic Thy1.1+ BALB/c mice were a gift from Dr Dutton (Trudeau Institute, Saranac Lake, NY), and C57BL/6 and BABL/c mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD). Influenza hemagglutinin (HA)–specific I-Ed–restricted CD4 TCR-transgenic mice (in BALB/c background, Thy1.2) were a gift from Dr Bona (Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY). All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the animal guidelines of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

Recombinant adenoviral vectors, mouse model with liver metastases, and therapeutic protocol

The construction of Adv.mIL-12, a replication-defective adenoviral vector carrying the murine IL-12 genes under the transcriptional control of the Rous sarcoma virus long terminal repeat (RSV-LTR) promoter, has been described previously.1 Metastatic colon cancer was induced by injecting 9 × 104 MCA26 cells into the left lateral lobe of the livers of 8- to 10-week-old female mice (National Cancer Institute) as described previously.1,28 At day 9 after tumor implantation, mice with liver tumors that measured 10 × 10 to 12 × 12 mm2 in diameter were selected and given 3 × 1010 viral particles of Adv.mIL-12 or control DL312 (E1A-deleted control adenoviral vector) intratumorally. The next day following viral injection, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 100 μg agonistic monoclonal anti–4–1BB antibody or control rat Ig (Accurate Chemical & Scientific, Westbury, NY) and 50 μg blocking monoclonal anti-ckit antibody or control rat Ig, at days 1 and 3 and days 1, 4, 7, 10, and 13, respectively. Anti-ckit hybridoma (ACK2) was kindly provided by Dr Nakashima of Chubu University, Kasugai City, Japan.37

Peptide, antibodies, and immunostaining of tumor tissue

CD4 HA peptide (110SFERFEIFPKE120) was purchased from Washington Biotechnology (Baltimore, MD). Anti–Thy1.2-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), anti–Gr-1-APC or -FITC, anti–CD115-PE, anti–F4/80-FITC, anti–CD11b-APC or -FITC, anti–CD25-APC, anti–FoxP3-PE, and isotype-matched monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Immunostaining of tumor tissues was performed using biotinylated anti–Gr-1 or anti-CD11b (eBioscience), followed by Cy3-conjugated streptavidin (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). The staining of endothelial cells was performed using rat anti–mouse CD31 followed by Cy3-conjugated donkey anti–rat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch).

Isolation of MDSCs and tumor-infiltrating T cells

Mice with tumor sizes of 12 × 12 to 15 × 15 mm2 were killed and the spleens, tibias, and femurs were harvested. After lysis of red blood cells, bone marrow cells and splenocytes were fractionated by centrifugation on a Percoll (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden) density gradient as previously described.12,26 Cells were collected from the gradient interfaces. Cells banding between 40% and 50% were labeled as fraction 1 (Fr. I); between 50% and 60% as fraction 2 (Fr. II); and between 60% and 70% as fraction 3 (Fr. III).

Tumor infiltrating leukocytes were isolated from tumor tissues as described previously.1 The CD3+ T cells were purified from T-cell enrichment column per manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

In all of the sorting experiments, very stringent gating conditions were used (FACSVantage with FACSDiVa). The purity of the sorted cells was checked by flow cytometry and sorted cell populations that were greater than 97% pure MDSCs or T cells were chosen and used in the experiments.

MDSC suppression assay

The suppressive activity of MDSCs was assessed in a peptide-mediated proliferation assay of TCR transgenic T cells as described previously.11 Briefly, the splenocytes (1 × 105) from TCR-transgenic mice were cultured in the presence of HA peptides (5 μg/mL) and serial dilutions of irradiated (850 rad) MDSCs in 96-well microplates. [3H]-thymidine was added during the last 8 hours of a 72-hour culture.

Cytokine detection by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Cytokine concentrations in culture supernatants were measured by using mouse IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, IFN-γ, TGF-β1, and IL-12p70 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (R&D Systems) per the manufacturer's instructions. Mock-transfected control and SCF-silenced MCA26 cell clones (1 × 106/mL) were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 100 μM PMSF, 1% aprotinin, 2 μg/mL leupeptin, and 1 μg/mL pepstatin. For cell lysate preparation, tumor cells were frozen and thawed thrice between −20°C and room temperature, followed by high-speed centrifugation (12 000g). The clear supernatants were collected for the measurement of murine SCF by ELISA (R&D Systems).

Adoptive transfer experiments

Thy1.2 congenic CD4 or CD8 HA-specific TCR-transgenic T cells were enriched by T-cell enrichment columns per the manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems) for adoptive transfer through tail-vein injection (5 × 106 cells/mouse). As for preparation of MDSCs, sorted Gr-1+CD115+ Fr. II cells (2.5 × 106/mouse) from large tumor-bearing mice were used. HA-MCA26 cells (or neo transfected parental MCA26 cells as a control; 9 × 104) were inoculated into Thy1.1+ BALB/c mice. After 6 days, the mice with a tumor size of around 5 × 5 mm2 were irradiated with high-dose radiation (850 rad) to eradicate endogenous MDSCs and T cells, which was confirmed by flow cytometric analysis of Gr-1+CD115+ cells and T cells in bone marrow and spleen of irradiated mice (less than 0.5% of T cells and MDSCs were present in the irradiated recipient mice). The sorted MDSCs and T cells were coadoptively transferred through tail vein on the following day. Mice were killed at day 10 after the adoptive transfer and Thy1.2+ T cells were recovered from spleen and lymph nodes of recipient mice by cell sorting.

Proliferation assay

The sorted Thy1.2+ or column-enriched T cells (1 × 104) were cocultured with irradiated (2500 rad) naive splenic cells (4 × 103; as antigen-presenting cells) in the presence or absence of HA peptide (5 μg/mL) in 96-well microplates. [3H]-thymidine was added during the last 8 hours of a 72-hour culture.

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Target cells were homogenized in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and total RNA was extracted per the manufacturer's instructions. A reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) procedure was used to determine relative quantities of mRNA (One-step RT-PCR kit; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Twenty-eight PCR cycles were used for all of the analyses. The intensity of each amplified DNA band was further analyzed by IQ Mac v1.2 software and relatively quantitated using GAPDH as the internal control. The primers for the genes analyzed were purchase from Gene Link and include internal control GAPDH: 5′-GTGGAGATT-GTTGCCATCAACG-3′(sense), 5′-CAGTGGATGCAGGGATGATGTTCTG-3′ (antisense); Foxp3: 5′-CAGCTGCCTACAGTGCCCCTAG-3′ (sense), 5′-CATTTG CCAGCAGTGGGTAG-3′ (antisense); SCF: 5′-GCTTGACTACTCTTCTGGAC-3′ (sense), 5′-CTCTCTCTTTCTGTTGGAAC -3′ (antisense). For quantitative real-time PCR, 2 μL cDNA reversely transcribed from total RNA was amplified by real-time quantitative PCR with 1× Syber green universal PCR Mastermix (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). Each sample was analyzed in duplicate with the IQ-Cycler (Bio-Rad) and the normalized signal level was calculated based on the ratio to the respective glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) housekeeping signal.

Results

Identification of the tumor factors involved in MDSC accumulation and reversion of T-cell tolerance by siRNA silencing of tumor factor

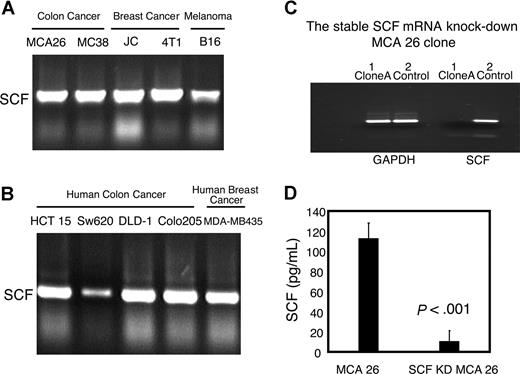

To identify candidate tumor factors that are involved in MDSC accumulation, we performed a gene expression profile analysis of colon MCA26 tumor tissues using GEArray Q Series Mouse Common Cytokines Gene Array (SuperArray, Frederick, MD). Several candidate genes were identified, and one of the most highly expressed cytokines in tumor cell lines and tumor tissue was found to be SCF. The expression of SCF was further confirmed using RT-PCR in multiple murine and human tumor cell lines of multiple tissue origins, including colon, breast, and melanoma (Figure 1A,B).

Expression of SCF by various murine and human tumor cell lines from multiple tissue origins and establishment of SCF-silenced tumor clones. (A) SCF expression in various murine tumor cell lines (colon cancer: MCA26, MC38; breast cancer: JC, 4T1; melanoma: B16). (B) SCF expression in various human tumor cell lines (colon cancer: HCT15, SW620, DLD-1, Colo205; breast cancer: MDA-MB435). Total RNAs were prepared from the murine and human tumor cell lines and SCF mRNA expressions were analyzed by RT-PCR. (C) SCF expression in SCF-silenced MCA26 clone and in control mock-transfected clone. Multiple stable SCF knockdown and mock-transfected control MCA26 clones were established as described in “Methods.” RNAs were prepared from representative clones and SCF expressions were analyzed by RT-PCR. (D) The protein expression of SCF in mock-transfected control and SCF-silenced MCA26 clones. Cell lysates were prepared and SCF concentration was measured by ELISA.

Expression of SCF by various murine and human tumor cell lines from multiple tissue origins and establishment of SCF-silenced tumor clones. (A) SCF expression in various murine tumor cell lines (colon cancer: MCA26, MC38; breast cancer: JC, 4T1; melanoma: B16). (B) SCF expression in various human tumor cell lines (colon cancer: HCT15, SW620, DLD-1, Colo205; breast cancer: MDA-MB435). Total RNAs were prepared from the murine and human tumor cell lines and SCF mRNA expressions were analyzed by RT-PCR. (C) SCF expression in SCF-silenced MCA26 clone and in control mock-transfected clone. Multiple stable SCF knockdown and mock-transfected control MCA26 clones were established as described in “Methods.” RNAs were prepared from representative clones and SCF expressions were analyzed by RT-PCR. (D) The protein expression of SCF in mock-transfected control and SCF-silenced MCA26 clones. Cell lysates were prepared and SCF concentration was measured by ELISA.

Because SCF plays an essential role in the early and late stages of hematopoiesis, we hypothesize that SCF derived from tumor cells may regulate the accumulation of MDSCs by simultaneously enhancing myelopoiesis and attenuating monocyte/granulocyte/DC differentiation.

To determine the role of tumor-derived SCF in the development and expansion of MDSCs, we established several stable SCF knockdown MCA26 cell clones using siRNA specific for SCF (Figure 1C). We further determined the effect of RNA silencing on protein expression of SCF using cell lysate prepared from control or SCF-silenced tumor cells. The results indicate that SCF protein expressed by silenced tumor cells is significantly lower than that of control tumor cells. The mice bearing SCF-silenced MCA26 tumors had a significantly lower percentage Gr-1+CD115+ MDSCs (13.0% ± 2.9%) compared with those bearing mock-transfected control MCA26 tumors (27.67% ± 2.78%; P < .005; Student t test; Figure 2A). These results indicate that the ablation of tumor-derived SCF alone can have a significant impact on the accumulation of MDSCs.

Tumor-derived SCF is required for MDSC accumulation in the tumor-bearing mice. (A) Decreased percentage of Gr-1+CD115+ MDSCs in bone marrow of mice bearing SCF knockdown tumors. BM Percoll fraction II (Fr. II) cells from mice bearing SCF-silenced (4 mice) versus control mock-transfected (5 mice) MCA26 tumors were stained with anti–Gr-1-APC plus anti–CD115-PE or isotype control antibodies followed by flow cytometric analysis. The percentage of MDSCs in mice bearing SCF-silenced tumors is significantly lower than that in mice bearing control tumors (P < .001 by Student t test). (B) Decreased number of Gr-1+CD115+ cells in mice bearing SCF knockdown tumors. The numbers of Gr-1+CD115+CD11b+ and Gr-1+CD115-CD11b+ cells in bone marrow Fr. II derived from mice with large ( > 10 × 10 mm2), medium (7 × 7 mm2), or small ( < 7 × 7 mm2) control versus SCF-silenced tumors were compared. The average numbers of MDSCs in BM are presented. A significantly lower number of MDSCs were observed in mice bearing SCF knockdown tumors with sizes larger than 7 × 7 mm2 compared with mice bearing control wild-type (WT) tumors (*P < .05, Student t test). (C) Reduced suppressive activity of Percoll Fr. II cells isolated from mice bearing SCF knockdown tumors. The suppressive activities of Percoll Fr. II, which contains MDSCs, isolated from mice bearing large SCF knockdown or control wild-type tumors were assessed using HA peptide-mediated proliferation at various ratios of CD4 HA TCR transgenic splenocytes/irradiated Fr. II cells. The Fr. III cells were used as negative control. The Fr. II cells from mice with SCF knockdown tumors exhibited lower suppressive activity compared with those from mice bearing wild-type tumors. Con indicates control. (D) Proliferative response of T cells derived from tumor tissues. The anti-CD3/anti-CD28–mediated proliferative responses of the T cells derived from SCF-silenced or control tumor tissues were assessed in a standard [3H]-thymidine incorporation assay. Splenocytes from naive normal mice were used as a positive control. w/o indicates without.

Tumor-derived SCF is required for MDSC accumulation in the tumor-bearing mice. (A) Decreased percentage of Gr-1+CD115+ MDSCs in bone marrow of mice bearing SCF knockdown tumors. BM Percoll fraction II (Fr. II) cells from mice bearing SCF-silenced (4 mice) versus control mock-transfected (5 mice) MCA26 tumors were stained with anti–Gr-1-APC plus anti–CD115-PE or isotype control antibodies followed by flow cytometric analysis. The percentage of MDSCs in mice bearing SCF-silenced tumors is significantly lower than that in mice bearing control tumors (P < .001 by Student t test). (B) Decreased number of Gr-1+CD115+ cells in mice bearing SCF knockdown tumors. The numbers of Gr-1+CD115+CD11b+ and Gr-1+CD115-CD11b+ cells in bone marrow Fr. II derived from mice with large ( > 10 × 10 mm2), medium (7 × 7 mm2), or small ( < 7 × 7 mm2) control versus SCF-silenced tumors were compared. The average numbers of MDSCs in BM are presented. A significantly lower number of MDSCs were observed in mice bearing SCF knockdown tumors with sizes larger than 7 × 7 mm2 compared with mice bearing control wild-type (WT) tumors (*P < .05, Student t test). (C) Reduced suppressive activity of Percoll Fr. II cells isolated from mice bearing SCF knockdown tumors. The suppressive activities of Percoll Fr. II, which contains MDSCs, isolated from mice bearing large SCF knockdown or control wild-type tumors were assessed using HA peptide-mediated proliferation at various ratios of CD4 HA TCR transgenic splenocytes/irradiated Fr. II cells. The Fr. III cells were used as negative control. The Fr. II cells from mice with SCF knockdown tumors exhibited lower suppressive activity compared with those from mice bearing wild-type tumors. Con indicates control. (D) Proliferative response of T cells derived from tumor tissues. The anti-CD3/anti-CD28–mediated proliferative responses of the T cells derived from SCF-silenced or control tumor tissues were assessed in a standard [3H]-thymidine incorporation assay. Splenocytes from naive normal mice were used as a positive control. w/o indicates without.

We further determined the effect of tumor size on the accumulation of MDSCs (Gr-1+CD115+) in the bone marrow Percoll fraction II (Fr. II) of SCF-silenced versus parental tumor-bearing mice. The results indicate that mice bearing large (> 10 × 10 mm2) or medium (7 × 7 to 10 × 10 mm2) SCF-knockdown tumors have fewer MDSCs compared with those bearing control mock-transfected tumors. We also assessed the effect of SCF silencing on the accumulation of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells, which also belong to the MDSC population in various tumor models.19,24,25 SCF silencing in MCA26 tumor cells also resulted in a significant decrease in the number of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in mice bearing large tumors (> 7 × 7 mm2). A less significant difference was observed in mice with small tumors at which stage the accumulation of MDSCs is not evident (Figure 2B). More importantly, the bone marrow Fr. II cells, which contain MDSCs from SCF knockdown tumor-bearing mice, exhibit less suppressive activity compared with those from mice that were injected with control mock-transfected tumor cells (Figure 2C). Furthermore, the T cells isolated from the SCF-silenced tumor tissue exhibited a higher proliferative response to anti-CD3/anti-CD28 stimulation compared with those from control tumor tissue, indicating that the microenvironment of SCF-silenced tumors is less tolerogenic compared with that of control tumors (Figure 2D). Taken together, these results suggest that SCF derived from tumor cells may play an important role in MDSC accumulation, which, in turn, exerts an inhibitory effect on T-cell responses.

Blocking SCF function results in the prevention of T-cell anergy

Because of the effect of SCF silencing in tumors on MDSC accumulation and suppressive activity, we hypothesize that blocking SCF/ckit (SCF receptor) signaling by the use of anti-ckit treatment can reduce MDSC accumulation and prevent T-cell anergy in mice with large tumor burdens. Mice bearing MCA26 tumors were injected with various doses of purified anti-ckit antibodies every 3 days for a total of 4 doses. T cells were isolated from tumor tissues of anti-ckit– or control rat Ig (100 μg)–treated mice and stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28. The results indicate that anti-ckit antibody at doses of 50 μg or 100 μg, but not 25 μg, are sufficient to render the tumor microenvironment less tolerogenic (Figure 3A), possibly due to the decrease in MDSCs. To test this possibility, we further determined the effect of anti-ckit treatment on MDSC expansion and accumulation. The tumor-bearing mice treated with the lowest effective dose of anti-ckit blocking antibody (50 μg) significantly reduced the MDSC population from 50.9% plus or minus 7.703% to 14.66% plus or minus 3.066%, P < .001 (Figure 3B). Furthermore, the MDSCs isolated from the bone marrow and spleens of anti-ckit–treated, tumor-bearing mice exhibited significantly reduced suppressive activity compared with MDSCs isolated from control Ig–treated, tumor-bearing mice (Figure 3C). The results demonstrate that the treatment of anti-ckit can effectively suppress MDSC expansion and accumulation and can decrease MDSC suppressive function.

Proliferative responses of T cells isolated from tumor tissues after the treatment of anti-ckit antibodies. (A) Proliferative response of T cells derived from tumor tissues of anti-ckit– or control Ig–treated mice. The anti-CD3/anti-CD28–mediated proliferative responses of the T cells derived from tumor tissues were assessed in a standard [3H]-thymidine incorporation assay. Splenic T cells purified from naive mice were used as positive control. Stimulation index (SI; cpm in the presence of anti-CD3/anti-CD28 divided by cpm in the absence of anti-CD3/anti-CD28) of the result is presented. (B) Decreased percentage of Gr-1+CD115+ MDSCs in bone marrow of tumor-bearing mice treated with anti-ckit. BM Percoll Fraction 2 cells from tumor-bearing mice treated with anti-ckit or control rat Ig were stained with anti–Gr-1-APC plus anti–CD115-PE or isotype control antibodies followed by flow cytometric analysis. A significantly lower percentage of MDSCs was observed in tumor-bearing mice treated with anti-ckit compared with those treated with control rat Ig (P < .001 by Student t test). Numbers in quadrants represent percent positive. (C) Reduced suppressive activity of MDSCs isolated from tumor-bearing mice treated with anti-ckit. The suppressive activities of MDSCs were assessed using HA peptide-mediated proliferation at various ratios of CD4 HA TCR transgenic splenocytes and MDSCs. The MDSCs isolated from mice treated with anti-ckit exhibited lower suppressive activity compared with those from mice receiving control rat Ig. Error bars represent standard deviation.

Proliferative responses of T cells isolated from tumor tissues after the treatment of anti-ckit antibodies. (A) Proliferative response of T cells derived from tumor tissues of anti-ckit– or control Ig–treated mice. The anti-CD3/anti-CD28–mediated proliferative responses of the T cells derived from tumor tissues were assessed in a standard [3H]-thymidine incorporation assay. Splenic T cells purified from naive mice were used as positive control. Stimulation index (SI; cpm in the presence of anti-CD3/anti-CD28 divided by cpm in the absence of anti-CD3/anti-CD28) of the result is presented. (B) Decreased percentage of Gr-1+CD115+ MDSCs in bone marrow of tumor-bearing mice treated with anti-ckit. BM Percoll Fraction 2 cells from tumor-bearing mice treated with anti-ckit or control rat Ig were stained with anti–Gr-1-APC plus anti–CD115-PE or isotype control antibodies followed by flow cytometric analysis. A significantly lower percentage of MDSCs was observed in tumor-bearing mice treated with anti-ckit compared with those treated with control rat Ig (P < .001 by Student t test). Numbers in quadrants represent percent positive. (C) Reduced suppressive activity of MDSCs isolated from tumor-bearing mice treated with anti-ckit. The suppressive activities of MDSCs were assessed using HA peptide-mediated proliferation at various ratios of CD4 HA TCR transgenic splenocytes and MDSCs. The MDSCs isolated from mice treated with anti-ckit exhibited lower suppressive activity compared with those from mice receiving control rat Ig. Error bars represent standard deviation.

Enhancing tumor regression and prevention of anergy of tumor (HA)–specific T cells by blocking SCF function

Because MDSCs can mediate suppression of tumor-specific T-cell responses in tumor-bearing mice, we further investigated whether blocking the expansion of MDSCs by the use of anti-ckit antibodies could prevent tumor-specific T-cell anergy in the HA-MCA26 tumor-bearing model.11 BALB/c mice were intrahepatically inoculated with HA-MCA26 tumor cells or control MCA26 tumor. At day 9, one group of mice received 5 × 106 adoptively transferred HA-TCR T cells in combination with control Ig, one group with HA-TCR T cells and anti-ckit, another group with anti-ckit alone, and the last group with rat Ig alone as a control. We assessed the immune response of adoptively transferred tumor (HA)–specific T cells (Thy1.2+ CD4 HA TCR transgenic T cells) in recipient congenic Thy1.1+ HA-MCA26 or control MCA26 tumor-bearing mice treated with anti-ckit or control Ig (50 μg/mouse) every 3 days for a total of 4 doses. As expected, the sorted Thy1.2+ CD4 HA TCR transgenic T cells isolated from rat Ig–treated HA-MCA26 tumor-bearing animals proliferated poorly in response to HA peptide stimulation. Interestingly, transferred tumor (HA)–specific T cells recovered from anti-ckit–treated HA-MCA26 tumor-bearing mice exhibited significantly higher proliferative responses to in vitro restimulation with HA peptide compared with those recovered from rat Ig–treated recipient mice. The proliferative response was even higher, although not significantly, compared with that using cells isolated from MCA26 control (without HA antigen) tumor-bearing animals (Figure 4A). The residual tumor tissue was carefully resected and weighed. The tumor weight from anti-ckit–treated animals was significantly lower than that of rat Ig–treated mice (Figure 4B, P < .001). More significantly, some of the mice that received anti-ckit treatment and transfer of tumor (HA)–specific T cells became tumor-free (by pathologic examination of the entire liver at the day of termination). The residual tumors from mice that received anti-ckit treatment were pale in color and were less vascular compared with those from the rat Ig–treated, tumor-bearing animals.

Treatment of anti-ckit prevents the development of T-cell anergy in tumor-bearing mice. Thy1.2+ CD4 HA-specific TCR-transgenic T cells (5 × 106/mouse) were injected via tail vein into congenic Thy1.1+ MCA26 or HA-MCA26 tumor-bearing mice 3 days after the first dose of anti-ckit or rat Ig injection (50 μg/mouse). At day 15 after transfer, Thy1.2+ splenocytes were recovered by sorting. (A) Proliferative responses of sorted Thy1.2+ CD4 HA-specific T cells to HA peptides. The culture was pulsed with [3H]-thymidine for the last 8 hours of a 72-hour culture. Stimulation index (SI) is calculated as the proliferation count (cpm) in the presence of HA peptide divided by that in the absence of HA peptide. Data shown are from a representative of 2 reproducible experiments (3 to 4 mice per group). *P <.001 (B) The residual tumor weight. The residual tumors were resected from the liver tissue and the tumor weight (gram) was measured. Error bars represent standard deviation. (C) The expression of Foxp3 in tumor (HA)–specific T cells. RNA was prepared from Thy1.2+ CD4 HA TCR transgenic T cells recovered from treated mice and Foxp3 expression was analyzed by one-step RT-PCR and real-time PCR. GAPDH expression was used as housekeeping gene control. (D) Intracellular staining of Foxp3 in tumor (HA)–specific T cells. Splenocytes were prepared from treated mice and stained with fluorochrome-conjugated anti-Thy1.2 (FITC) plus anti-CD4 (APC) plus anti-CD25 (PE-Cy7) plus anti-Foxp3 (PE). Thy1.2+CD4+ gated dot plots are presented. Naive mice with adoptively transferred T cells and rat Ig (left); tumor-bearing mice with adoptively transferred CD4 T cells and rat Ig control (middle); tumor-bearing mice with adoptively transferred T cells and anti-ckit (right). (E) Cytokine profile of tumor-specific T cells. Culture supernatants of recovered Thy1.2+ CD4 HA TCR transgenic T cells in the presence of HA peptide (5 μg/mL) and irradiated antigen-presenting cells (naive splenocytes) were collected. The naive CD4 HA TCR splenocytes cultured in the presence or absence of HA peptide were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The cytokine concentrations were measured by ELISA kits (R&D Systems). The cytokine profile of supernatant collected from culture of tumor (HA)–specific T cells skewed toward a Th1 response with a higher concentration of IFN-γ and a lower concentration of IL-10 (*P < .05; Student t test).

Treatment of anti-ckit prevents the development of T-cell anergy in tumor-bearing mice. Thy1.2+ CD4 HA-specific TCR-transgenic T cells (5 × 106/mouse) were injected via tail vein into congenic Thy1.1+ MCA26 or HA-MCA26 tumor-bearing mice 3 days after the first dose of anti-ckit or rat Ig injection (50 μg/mouse). At day 15 after transfer, Thy1.2+ splenocytes were recovered by sorting. (A) Proliferative responses of sorted Thy1.2+ CD4 HA-specific T cells to HA peptides. The culture was pulsed with [3H]-thymidine for the last 8 hours of a 72-hour culture. Stimulation index (SI) is calculated as the proliferation count (cpm) in the presence of HA peptide divided by that in the absence of HA peptide. Data shown are from a representative of 2 reproducible experiments (3 to 4 mice per group). *P <.001 (B) The residual tumor weight. The residual tumors were resected from the liver tissue and the tumor weight (gram) was measured. Error bars represent standard deviation. (C) The expression of Foxp3 in tumor (HA)–specific T cells. RNA was prepared from Thy1.2+ CD4 HA TCR transgenic T cells recovered from treated mice and Foxp3 expression was analyzed by one-step RT-PCR and real-time PCR. GAPDH expression was used as housekeeping gene control. (D) Intracellular staining of Foxp3 in tumor (HA)–specific T cells. Splenocytes were prepared from treated mice and stained with fluorochrome-conjugated anti-Thy1.2 (FITC) plus anti-CD4 (APC) plus anti-CD25 (PE-Cy7) plus anti-Foxp3 (PE). Thy1.2+CD4+ gated dot plots are presented. Naive mice with adoptively transferred T cells and rat Ig (left); tumor-bearing mice with adoptively transferred CD4 T cells and rat Ig control (middle); tumor-bearing mice with adoptively transferred T cells and anti-ckit (right). (E) Cytokine profile of tumor-specific T cells. Culture supernatants of recovered Thy1.2+ CD4 HA TCR transgenic T cells in the presence of HA peptide (5 μg/mL) and irradiated antigen-presenting cells (naive splenocytes) were collected. The naive CD4 HA TCR splenocytes cultured in the presence or absence of HA peptide were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The cytokine concentrations were measured by ELISA kits (R&D Systems). The cytokine profile of supernatant collected from culture of tumor (HA)–specific T cells skewed toward a Th1 response with a higher concentration of IFN-γ and a lower concentration of IL-10 (*P < .05; Student t test).

To determine the mechanism underlying the blockade of T-cell tolerance by anti-ckit antibodies, tumor-specific (CD4 HA TCR transgenic) T cells were recovered from anti-ckit–treated mice by cell sorting (Thy1.2+ cells). The level of Foxp3 (a transcriptional factor specifically expressed in murine Tregs) expression by the recovered tumor-specific T cells was analyzed by RT-PCR, real-time PCR, and intracellular staining. As shown in Figure 4C, tumor-specific T cells recovered from mice treated with control rat Ig expressed a high level of Foxp3, whereas those recovered from mice treated with anti-ckit expressed a significantly lower level of Foxp3. Consistent with the results from Foxp3 mRNA analysis, a significantly lower percentage (4.2%) of Foxp3+ tumor-specific T cells was detected in mice receiving anti-ckit compared with mice treated with control rat Ig (14.1%; Figure 4D). Furthermore, on in vitro stimulation with HA peptide, T cells recovered from mice treated with anti-ckit secreted higher levels of IFN-γ and lower levels of suppressive cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β compared with those from mice treated with control rat Ig (Figure 4E). Furthermore, a higher concentration of IL-12 was detected in the supernatant from the culture of T cells recovered from anti-ckit–treated group in the presence of antigen-presenting cells and HA peptides. The results demonstrate that anti-ckit can prevent T-cell anergy and Treg development.

Prevention of MDSC accumulation is correlated with the inhibition of angiogenesis of SCF-silenced tumor and tumor from anti-ckit–treated mice

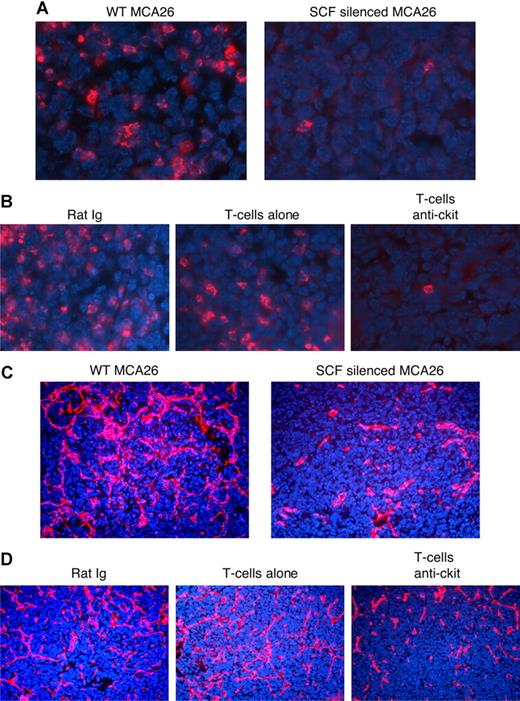

We further confirmed whether blocking SCF/ckit signaling by the use of anti-ckit or SCF-siRNA knockdown in MCA26 tumor cells could significantly reduce MDSC accumulation at the tumor sites. The immunostaining for markers of MDSCs was performed. The results indicated that Gr-1– or CD11b-positive (data not shown) cells are significantly reduced in SCF-siRNA–silenced tumors and in tumor tissues from anti-ckit–treated mice compared with control wild-type tumors or tumor tissues from control rat Ig–treated mice (Figure 5A,B).

Blockade of SCF/ckit pathway by the use of anti-ckit antibody or SCF knockdown of tumor cells results in decreased infiltration of MDSCs in tumor tissue and decreased tumor angiogenesis. (A) Immunostaining of Gr-1+ cells in wild-type versus SCF-silenced MCA26 tumor tissues. (B) Immunostaining of Gr-1+ cells in tumor tissues from HA-MCA26 tumor-bearing mice that were injected with rat Ig (left), 5 × 106 HA-TCR T cells (middle), or 5 × 106 HA-TCR T cells and anti-ckit (right). (C) Immunostaining of CD31+ cells in wild-type versus SCF-silenced MCA26 tumor tissues. (D) Immunostaining of CD31+ cells in tumor tissues from HA-MCA26 tumor-bearing mice that were injected with rat Ig (left), 5 × 106 HA-TCR T cells (middle), or 5 × 106 HA-TCR T cells and anti-ckit (right). Slides were viewed with a Leica DM RA2 fluorescent microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) using an HC PLAN APO lens at 63×/1.32 (A,B) and 40×/0.85 (C,D) and Klear Mount medium (GBI, Mukilteo, WA). Images were acquired using a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER digital camera (Minneapolis, MN) Model C4742-80-12AG, and were processed with Openlab version 5.02 (Improvision, Waltham, MA) and Adobe Photoshop version 7.0 software (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

Blockade of SCF/ckit pathway by the use of anti-ckit antibody or SCF knockdown of tumor cells results in decreased infiltration of MDSCs in tumor tissue and decreased tumor angiogenesis. (A) Immunostaining of Gr-1+ cells in wild-type versus SCF-silenced MCA26 tumor tissues. (B) Immunostaining of Gr-1+ cells in tumor tissues from HA-MCA26 tumor-bearing mice that were injected with rat Ig (left), 5 × 106 HA-TCR T cells (middle), or 5 × 106 HA-TCR T cells and anti-ckit (right). (C) Immunostaining of CD31+ cells in wild-type versus SCF-silenced MCA26 tumor tissues. (D) Immunostaining of CD31+ cells in tumor tissues from HA-MCA26 tumor-bearing mice that were injected with rat Ig (left), 5 × 106 HA-TCR T cells (middle), or 5 × 106 HA-TCR T cells and anti-ckit (right). Slides were viewed with a Leica DM RA2 fluorescent microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) using an HC PLAN APO lens at 63×/1.32 (A,B) and 40×/0.85 (C,D) and Klear Mount medium (GBI, Mukilteo, WA). Images were acquired using a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER digital camera (Minneapolis, MN) Model C4742-80-12AG, and were processed with Openlab version 5.02 (Improvision, Waltham, MA) and Adobe Photoshop version 7.0 software (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

A previous report by Yang et al38 has shown that Gr-1+CD11b+ MDSCs promote tumor growth by participation in tumor angiogenesis. Therefore, we reasoned that prevention of MDSC accumulation, either by SCF silencing in tumor or by the treatment of anti-ckit antibody, could result in reduced angiogenesis in the tumor site. The immunostaining of CD31+ endothelium cells was performed. The SCF-siRNA knockdown MCA26 tumor or the HA-MCA26 tumor tissue from mice that had received HA-specific T-cell and anti-ckit treatment showed significantly reduced blood vessel formation compared with control wild-type tumors or with tumors from mice receiving T-cell transfer alone or in conjunction with control rat Ig injection (Figure 5C,D). These results indicate that a reduction of SCF expression in tumor cells or treatment with anti-ckit antibody can significantly prevent both MDSC development and tumor angiogenesis.

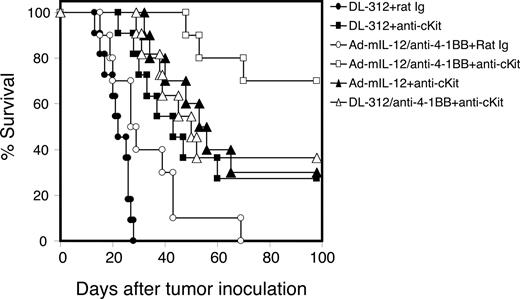

Blocking SCF function can enhance immune-enhancing cancer therapy

We have demonstrated that activated immune therapy in large tumor-bearing mice is significantly hampered by immune tolerance.1 Because MDSCs and Tregs are involved in the down-regulation of antitumor responses, we next determined whether blockade of MDSC accumulation and the consequences of that blockade (ie, decreased Treg development and T-cell tolerance) could, by the treatment of anti-ckit, further enhance the therapeutic efficacy of Adv.mIL-12 plus 4–1BB activation therapy.39 Mice with large tumors (ranging from 10 × 10 to 12 × 12 mm2) were randomly divided into various treatment groups. Starting 2 days before initiation (IL-12 plus 4-1BB activation) of the immune modulatory therapy, mice were injected intraperitoneally with anti-ckit or control rat Ig (50 μg) every 3 days for a total of 4 doses. Anti–4-1BB or control Ig (100 μg) was injected intraperitoneally on days 1 and 3 after the intratumoral injection of Adv.mIL-12 or control viral vector DL312. The long-term survival rate of treated mice was followed (Figure 6). All mice treated with control vector DL312 plus control Ig succumbed to death by day 30 after tumor implantation. The long-term survival rate of mice treated with anti-ckit plus Adv.mIL-12 plus 4-1BB activation is significantly higher than that of mice treated with Adv.mIL-12 plus 4-1BB activation (P < .001) or Adv.mIL-12 plus anti-ckit (P < .001). Adv.mIL-12 plus 4-1BB activation alone (P = .016) or anti-ckit alone (P = .036) also improved the long-term survival of treated mice compared with the control-treated (DL312 plus Ig) group. The results demonstrate that treatment with anti-ckit can significantly improve the therapeutic efficacy of IL-12 plus 4-1BB activation when treating large tumors. These results suggest that the prevention of MDSC accumulation may reduce MDSC-mediated immune suppression and Treg induction, which may improve the success rate for immune activation in the treatment of advanced malignancy.

Treatment of anti-ckit antibody significantly improves the long-term survival rate of mice treated with immune modulatory therapy of IL-12 plus 4-1BB activation. Mice bearing large MCA26 tumors (10 × 10 mm2) in the liver were divided into the following treatment groups: DL312 (control viral vector) plus control Ig; DL312 plus anti-ckit; Adv.mIL-12 plus anti–4-1BB plus rat Ig; Adv.mIL-12 plus anti–4-1BB plus anti-ckit; Adv.mIL-12 plus anti-ckit; and DL312 plus anti–4-1BB plus anti-ckit. The survival advantage for the mice treated with Adv.mIL-12 plus anti–4-1BB plus anti-ckit was statistically significant compared with those treated with Adv.mIL-12 plus anti–4-1BB plus rat Ig (P < .01, log-rank test).

Treatment of anti-ckit antibody significantly improves the long-term survival rate of mice treated with immune modulatory therapy of IL-12 plus 4-1BB activation. Mice bearing large MCA26 tumors (10 × 10 mm2) in the liver were divided into the following treatment groups: DL312 (control viral vector) plus control Ig; DL312 plus anti-ckit; Adv.mIL-12 plus anti–4-1BB plus rat Ig; Adv.mIL-12 plus anti–4-1BB plus anti-ckit; Adv.mIL-12 plus anti-ckit; and DL312 plus anti–4-1BB plus anti-ckit. The survival advantage for the mice treated with Adv.mIL-12 plus anti–4-1BB plus anti-ckit was statistically significant compared with those treated with Adv.mIL-12 plus anti–4-1BB plus rat Ig (P < .01, log-rank test).

Discussion

Several tumor factors (eg, VEGF, GM-CSF, M-CSF, IL-10, and TGFβ)11,28,30,32,40 and inflammatory cytokines (eg, IL-6 and IL-1β)41,42 have been implicated in the development of MDSCs. However, whether these tumor-derived or host factors are directly involved in MDSC-mediated Treg induction, immune tolerance, and development of MDSCs in tumor-bearing mice has not been well demonstrated. Furthermore, the therapeutic potential of blocking tumor factors to prevent MDSC-mediated immune suppression remains to be determined. Herein we report that tumor-derived SCF plays an important role in the expansion and accumulation of MDSCs. The reduction of SCF expression in tumor cells by siRNA knockdown resulted in not only a significant decrease in MDSC accumulation but also reversion of T-cell tolerance at the tumor site (Figure 2). Moreover, blocking SCF by the use of neutralizing antibodies enhanced antitumor responses as reflected by the increased tumor regression and prevention of tumor-specific T-cell tolerance (Figure 4). More importantly, controlling the abnormal accumulation of MDSCs in tumor-bearing mice through the blockade of the SCF/ckit pathway significantly improved the therapeutic efficacy of immune modulatory therapy in an advanced tumor model (Figure 6). To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that modulation of tumor factor expression can result in the decrease of MDSCs and the prevention of T-cell tolerance, leading to the enhanced efficacy of immune modulatory cancer therapy. Our results also serve as the proof of principle for the potential clinical application of SCF/ckit blockade in the prevention of immune tolerance as a complement to existing cancer immune therapeutic strategies for the treatment of advanced malignancies.

Although inhibition of SCF expression by tumor cells alone significantly reduced the percentage of MDSCs in spleen, it is possible that other factors and cytokines also contributed to the development and accumulation of MDSCs in mice with large tumor burdens. The tumor-associated inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, TNFα, and IL-18, can enhance SCF secretion by tumor cells,41,43,–45 and thereby further stimulate expansion of MDSCs. VEGF signaling through VEGFR-2 has been shown to promote myelopoiesis and accumulation of MDSCs46,47 through GM-CSF–dependent and –independent mechanisms.48 One conceivable mechanism by which SCF and VEGF work in concert to promote MDSC accumulation is that SCF increases and mobilizes myeloid progenitor cells and VEGF blocks the terminal differentiation of the mobilized myeloid progenitor cells.46 Furthermore, other myelopoietic factors, such as GM-CSF, M-CSF, and Flt3 ligand, may act synergistically with SCF to promote MDSC expansion. GM-CSF and SCF can synergistically promote the growth and differentiation of primitive hematopoietic cells.49 Taken together, it is therefore possible that growth stimulatory signals provided by SCF, VEGF, and other myelopoietic factors complement the differentiation inhibitory activity of VEGF to drive the expansion and accumulation of MDSCs in mice with advanced malignancies. The possible roles of these factors to synergistically promote MDSC accumulation in combination with SCF are currently under investigation.

SCF is involved in the normal developmental processes of multiple cell types (eg, gametogenesis, hematopoiesis, melanogenesis, and mast cells and endothelial cells).49 In this study, we found that a low dose of anti-ckit antibody (50 μg) was sufficient to block the effect of tumor-secreted SCF, leading to blockade of MDSC accumulation, and to revert immune tolerance in mice bearing large tumors without detectable adverse side effects or toxicities (Figure 3). SCF is also required for the development of certain types of cancer stem cells (eg, melanoma) and, at a minimum, stimulates tumor growth.50 Because treatment with anti-ckit alone yielded substantial survival benefit in mice bearing large tumors (Figure 6), targeting SCF/ckit may enhance the therapeutic efficacy of immune modulatory therapy for advanced tumors not only through prevention of MDSC-mediated immune suppression but also by direct inhibition of tumor growth.

Another important aspect of the study presented here is the added effect that blocking MDSC accumulation by targeting the SCF/ckit pathway has on tumor angiogenesis. Consistent with previous reports that MDSCs may directly promote tumor growth by participating in blood vessel formation within tumor tissue,38 we observed a significant reduction in angiogenesis within the tumors of mice treated with anti-ckit antibodies and in SCF-silenced tumors (Figure 5). Interestingly, MDSCs can regulate bioavailability of VEGF in tumors as well as the release of soluble SCF from bone marrow through the production of MMP9.38 Therefore, targeting the SCF/ckit pathway through the use of anti-ckit or siRNA knockdown in tumor cells may terminate a vicious cycle in which SCF secreted by tumor cells drives the expansion of MDSCs that in turn increase the availability of VEGF to promote tumor angiogenesis and tumor growth and the release of SCF from bone marrow. Furthermore, another potential beneficial outcome of preventing MDSC expansion through interference with SCF/ckit signaling is that MDSCs can undergo the appropriate terminal differentiation due to the removal of differentiation blockade mediated by VEGF.

Several lines of evidence support the notion that other cell types, such as mast cells,51 macrophages,52,53 plasmacytoid DCs,54,–56 and B cells57,58 may also be involved in T-cell tolerance. Blockade of the SCF/ckit pathway may influence the number and functional activity of these cells. For example, SCF is an important growth factor for mast cells and has been shown to induce the expression and release of various cytokines (eg, IL-4, IL-6, IL-13, and TNF-α) by mast cells.59 Furthermore, in an allograft tolerance model, mast cells are required for the regional immune suppression mediated by Tregs.51 Targeting SCF/ckit may also lead to decreases in the number of mast cells and their effector functions, which results in decreased Th2 responses and Treg suppressive activities. Studies are currently being conducted to determine the roles of other cell types with suppressive functions in the immune tolerance mediated by MDSCs and MDSC-induced Tregs.

SCF expression has been demonstrated in a number of human primary tumors (eg, melanoma, pancreatic cancer, colorectal carcinoma)60,,,–64 and can potentially be exploited for cancer treatment. Our studies demonstrate the feasibility and applicability of targeting the SCF/ckit pathway to prevent and revert immune tolerance mediated by MDSCs in mice with large tumor burdens. Blockade of MDSC expansion can lead to other beneficial antitumor effects, such as decreased tumor angiogenesis, a decreased number of Foxp3+ Tregs, and possibly suppressed Th2 responses and enhanced Th1 responses. Although we used antibody treatment and siRNA knockdown to interfere with the SCF/ckit pathway in the original proof-of-principle study, a class of receptor protein tyrosine kinase inhibitors (eg, imatinib mesylate, sunitinib malate, gefitnib, and lapatinib) has been used to treat patients with various malignancies, albeit with limited efficacies. This class of small molecule inhibitors suppresses ckit tyrosine kinase activity as well as other receptor tyrosine kinases, such as receptors of VEGF, PDGF, M-CSF, and EGF, all of which exert pro-tumor growth functions directly or indirectly. Therefore, our preclinical findings can be readily translated into the clinic by using clinically available small molecule inhibitors in conjunction with existing immune-based therapies for the treatment of advanced tumors.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Lieping Chen for providing anti–4-1BB monoclonal antibodies and Ms Marcia Meseck for editing of manuscript.

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Cancer Institute, the Sharp Foundation, and the Black Family Stem Cell Foundation (S.-H.C.); the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation (P.-Y.P.); and National Institutes of Health training grant fellowship T32CA078207-06 (J.O.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: P.-Y.P. designed and performed most of the research; G.X.W. and B.Y. performed additional research; J.O. analyzed data and performed research; T.K. provided a vital reagent; C.M.D. designed research; S.-H.C. designed research and supervised the project; and P.-Y.P. and S.-H.C. wrote the manuscript with valuable contribution from all other authors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Shu-Hsia Chen, Department of Gene and Cell Medicine, Box 1496, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, One Gustave L. Levy Place, New York, NY 10029; e-mail: shu-hsia.chen@mssm.edu.

![Figure 2. Tumor-derived SCF is required for MDSC accumulation in the tumor-bearing mice. (A) Decreased percentage of Gr-1+CD115+ MDSCs in bone marrow of mice bearing SCF knockdown tumors. BM Percoll fraction II (Fr. II) cells from mice bearing SCF-silenced (4 mice) versus control mock-transfected (5 mice) MCA26 tumors were stained with anti–Gr-1-APC plus anti–CD115-PE or isotype control antibodies followed by flow cytometric analysis. The percentage of MDSCs in mice bearing SCF-silenced tumors is significantly lower than that in mice bearing control tumors (P < .001 by Student t test). (B) Decreased number of Gr-1+CD115+ cells in mice bearing SCF knockdown tumors. The numbers of Gr-1+CD115+CD11b+ and Gr-1+CD115-CD11b+ cells in bone marrow Fr. II derived from mice with large ( > 10 × 10 mm2), medium (7 × 7 mm2), or small ( < 7 × 7 mm2) control versus SCF-silenced tumors were compared. The average numbers of MDSCs in BM are presented. A significantly lower number of MDSCs were observed in mice bearing SCF knockdown tumors with sizes larger than 7 × 7 mm2 compared with mice bearing control wild-type (WT) tumors (*P < .05, Student t test). (C) Reduced suppressive activity of Percoll Fr. II cells isolated from mice bearing SCF knockdown tumors. The suppressive activities of Percoll Fr. II, which contains MDSCs, isolated from mice bearing large SCF knockdown or control wild-type tumors were assessed using HA peptide-mediated proliferation at various ratios of CD4 HA TCR transgenic splenocytes/irradiated Fr. II cells. The Fr. III cells were used as negative control. The Fr. II cells from mice with SCF knockdown tumors exhibited lower suppressive activity compared with those from mice bearing wild-type tumors. Con indicates control. (D) Proliferative response of T cells derived from tumor tissues. The anti-CD3/anti-CD28–mediated proliferative responses of the T cells derived from SCF-silenced or control tumor tissues were assessed in a standard [3H]-thymidine incorporation assay. Splenocytes from naive normal mice were used as a positive control. w/o indicates without.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/111/1/10.1182_blood-2007-04-086835/3/m_zh80020811450002.jpeg?Expires=1769087091&Signature=RAo8RC9G26nTDZOyJS8eyHBSpibslGpOfsIv90XPHilUrstg5VRpDI2gHqcmKVNrpFN2VYRM~YMMfnWyIJhpyFdv222~djTQt3EKoTj5S61gnlOhMNVd9ao5YI63jLQnCMXKsOJWGaArobqbDyIG~JZZIxax4KUA6M92qOKsnDbPl4cIY2wlrRF~XQi27GP1KoyrtUAdSAvGPk72kfldTBSOgE~RP66QM5H5kPqpAB~KmoxO3u1JVApxeDEB82IaPARu8BDNGt1gTMAEFDdknWcPj-mmGkq2sH49HvOEmsfpUMqVfk6cXXIP2lyf4MGfWwzyZT-5MLxvcZdQZjEfBA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 3. Proliferative responses of T cells isolated from tumor tissues after the treatment of anti-ckit antibodies. (A) Proliferative response of T cells derived from tumor tissues of anti-ckit– or control Ig–treated mice. The anti-CD3/anti-CD28–mediated proliferative responses of the T cells derived from tumor tissues were assessed in a standard [3H]-thymidine incorporation assay. Splenic T cells purified from naive mice were used as positive control. Stimulation index (SI; cpm in the presence of anti-CD3/anti-CD28 divided by cpm in the absence of anti-CD3/anti-CD28) of the result is presented. (B) Decreased percentage of Gr-1+CD115+ MDSCs in bone marrow of tumor-bearing mice treated with anti-ckit. BM Percoll Fraction 2 cells from tumor-bearing mice treated with anti-ckit or control rat Ig were stained with anti–Gr-1-APC plus anti–CD115-PE or isotype control antibodies followed by flow cytometric analysis. A significantly lower percentage of MDSCs was observed in tumor-bearing mice treated with anti-ckit compared with those treated with control rat Ig (P < .001 by Student t test). Numbers in quadrants represent percent positive. (C) Reduced suppressive activity of MDSCs isolated from tumor-bearing mice treated with anti-ckit. The suppressive activities of MDSCs were assessed using HA peptide-mediated proliferation at various ratios of CD4 HA TCR transgenic splenocytes and MDSCs. The MDSCs isolated from mice treated with anti-ckit exhibited lower suppressive activity compared with those from mice receiving control rat Ig. Error bars represent standard deviation.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/111/1/10.1182_blood-2007-04-086835/3/m_zh80020811450003.jpeg?Expires=1769087091&Signature=ohaWJ5gFRq~ffzdvLcN2OwSgw~pKyBsZaHdqJ0kz0vIHs4ZTQB67DvEDZno50ALjgOwrbLoEO1ibCwuShcpdZoMLiAgWoZZBBx9xtolW6inM2pqFwuTBR59ejxkcw5YOT1TmWVrf8aN~w1zkTFUk1cNoE3Z72XEqBMvzpsXHrb0aA2sxNVkXVIkNp8dlbGYZVRvvKHSvHUnohi4jprt4VKDjv2aW~PUE6Vcn1LQ4aQmECY648lb-WGr~Z5E4JAgI8RVQp4eW2epcDKLsFq0cnzvmTgkqoAWFpvBbpFRKhbjD5fNmsrMiE8zMqnCAYLMDU8eksPWIKazQIqqiFYHTag__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 4. Treatment of anti-ckit prevents the development of T-cell anergy in tumor-bearing mice. Thy1.2+ CD4 HA-specific TCR-transgenic T cells (5 × 106/mouse) were injected via tail vein into congenic Thy1.1+ MCA26 or HA-MCA26 tumor-bearing mice 3 days after the first dose of anti-ckit or rat Ig injection (50 μg/mouse). At day 15 after transfer, Thy1.2+ splenocytes were recovered by sorting. (A) Proliferative responses of sorted Thy1.2+ CD4 HA-specific T cells to HA peptides. The culture was pulsed with [3H]-thymidine for the last 8 hours of a 72-hour culture. Stimulation index (SI) is calculated as the proliferation count (cpm) in the presence of HA peptide divided by that in the absence of HA peptide. Data shown are from a representative of 2 reproducible experiments (3 to 4 mice per group). *P <.001 (B) The residual tumor weight. The residual tumors were resected from the liver tissue and the tumor weight (gram) was measured. Error bars represent standard deviation. (C) The expression of Foxp3 in tumor (HA)–specific T cells. RNA was prepared from Thy1.2+ CD4 HA TCR transgenic T cells recovered from treated mice and Foxp3 expression was analyzed by one-step RT-PCR and real-time PCR. GAPDH expression was used as housekeeping gene control. (D) Intracellular staining of Foxp3 in tumor (HA)–specific T cells. Splenocytes were prepared from treated mice and stained with fluorochrome-conjugated anti-Thy1.2 (FITC) plus anti-CD4 (APC) plus anti-CD25 (PE-Cy7) plus anti-Foxp3 (PE). Thy1.2+CD4+ gated dot plots are presented. Naive mice with adoptively transferred T cells and rat Ig (left); tumor-bearing mice with adoptively transferred CD4 T cells and rat Ig control (middle); tumor-bearing mice with adoptively transferred T cells and anti-ckit (right). (E) Cytokine profile of tumor-specific T cells. Culture supernatants of recovered Thy1.2+ CD4 HA TCR transgenic T cells in the presence of HA peptide (5 μg/mL) and irradiated antigen-presenting cells (naive splenocytes) were collected. The naive CD4 HA TCR splenocytes cultured in the presence or absence of HA peptide were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The cytokine concentrations were measured by ELISA kits (R&D Systems). The cytokine profile of supernatant collected from culture of tumor (HA)–specific T cells skewed toward a Th1 response with a higher concentration of IFN-γ and a lower concentration of IL-10 (*P < .05; Student t test).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/111/1/10.1182_blood-2007-04-086835/3/m_zh80020811450004.jpeg?Expires=1769087091&Signature=xeQP4ynukBesQXPvkdbvdAHVBHtUJyyelVZ--Fj3bXntpchgN09gSCbe-fdUSn5Z0hy1XaRarZA600Wet7918~GlvleuK9-OAGVAMPPhxDmbZdj39HMcbiNIjEO7j1pHltWHFAxe3aOW027O7NaNQnoFnva5C8IaL3QVTgQaNR0hVj3fW6Y7OEvYJsa4LBqHDDPcKvAv02tVIh47TEODNt1mRVP14o28h8BYMZODNl52rIJ2Tlt5kLousO0XwpZZ0Mt1fa1s1gFD3U26zXIEihAaXrvW635odMq26npmmwim-tkdIV8JpfBWSfFuMGSh3MGvvX2b2N03VtTBSmdtPQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal