Abstract

We have studied a patient with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and t(10;11)(q23;p15) as the sole cytogenetic abnormality. Molecular analysis revealed a translocation involving nucleoporin 98 (NUP98) fused to the DNA-binding domain of the hematopoietically expressed homeobox gene (HHEX). Expression of NUP98/HHEX in murine bone marrow cells leads to aberrant self-renewal and a block in normal differentiation that depends on the integrity of the NUP98 GFLG repeats and the HHEX homeodomain. Transplantation of bone marrow cells expressing NUP98/HHEX leads to transplantable acute leukemia characterized by extensive infiltration of leukemic blasts expressing myeloid markers (Gr1+) as well as markers of the B-cell lineage (B220+). A latency period of 9 months and its clonal character suggest that NUP98/HHEX is necessary but not sufficient for disease induction. Expression of EGFP-NUP98/HHEX fusions showed a highly similar nuclear localization pattern as for other NUP98/homeodomain fusions, such as NUP98/HOXA9. Comparative gene expression profiling in primary bone marrow cells provided evidence for the presence of common targets in cells expressing NUP98/HOXA9 or NUP98/HHEX. Some of these genes (Hoxa5, Hoxa9, Flt3) are deregulated in NUP98/HHEX-induced murine leukemia as well as in human blasts carrying this fusion and might represent bona fide therapeutic targets.

Introduction

Experimental as well as clinical evidence supports a model of acute leukemia being the product of several functionally distinct cooperating genetic alterations: mutations leading to uncontrolled proliferation and/or survival, and mutations that primarily block normal blood cell maturation.1,2 Among the latter is a growing group of chromosomal translocations that involve the nucleoporin 98 (NUP98) gene on the short arm of chromosome 11, which is associated with de novo and therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia (AML), but is also found in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), myelodysplastic syndromes, and advanced stages of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).3-5 To date, fusions of NUP98 to more than 20 different partner genes, including homeobox genes (such as HOXA9, HOXD11, and others) and nonhomeobox genes (such as TOP1, NSD1 and NSD13, DDX1, or RAP1GDS1) have been found. Interestingly, in all fusions, the N-terminus of NUP98 containing GFLG (Gly-Phe-Lys-Gly) repeats is maintained. Some, but not all, of the currently known NUP98 fusion genes have been characterized for their transforming activity: the best studied, NUP98/HOXA9, provides aberrant self-renewal capacity, blocks myeloid differentiation in vitro, and induces an AML-like disease in vivo after long latency.6-8 Although other NUP98-homeodomain and nonhomedomain fusions (such as NUP98/NSD1) show similar (but not identical) transforming activities, no such activities have been reported for NUP98 fusions involving NSD3 or RAP1GDS1.9-13 Structure function studies have provided evidence that the NUP98 GFLG repeats are crucial for the oncogenic activity of NUP98/HOXA9 in a classical transformation assay using NIH-3T3 cells.14 A dynamic interaction of NUP98 GLFG repeats with transcriptional cofactors such as the activators CBP or p300, or repressors such as HDAC1, seems to be involved.15 Although the number of new NUP98 fusion genes reported is rising, as an individual event these alterations remain rare. However, since their presence is generally associated with a poor clinical prognosis, it is mandatory to define common molecular mechanisms to delineate new therapeutic avenues for these patients.

Here we characterize a new NUP98 fusion resulting from a t(10;11)(q23;p15) identified in leukemic blasts from an AML patient in relapse. NUP98 is fused to the hematopoietic homeobox gene HHEX also known as proline-rich homeobox (PRH).16-18 The resulting NUP98/HHEX fusion has transforming activity in vitro and in vivo, which is dependent on the GFLG repeats of NUP98 and the integrity of the HHEX homeodomain. Fusion to NUP98 transforms HHEX from a strong transcriptional repressor to a transcriptional activator. Comparative gene expression analysis revealed a partially overlapping target profile of NUP98/HHEX and NUP98/HOXA9. Our results suggest that it might be possible to delineate common critical targets for several NUP98 fusions (and other leukemogenic fusions containing transcriptional regulators) that are worth further validation as potential targets for therapeutic intervention.

Methods

Approval was obtained from the Ospedale V. Cervello ethical committee for these studies. Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Index patient

A 59-year-old male patient was diagnosed with AML (FAB-M2) in 1989. Cytogenetics was not performed. He underwent standard chemotherapy and complete hematologic remission was achieved. In 1994, the disease relapsed with bone marrow and skin infections treated with mitoxantrone, cytosine arabinoside, and etoposide. A second hematologic remission was obtained lasting until December 2002, when he came to our attention for fever, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. Peripheral blood counts were as follows: hemoglobin level, 91 g/L (9.1 g/dL); platelet count, 49 × 109/L; and white blood cell count, 2.35 × 109/L. Bone marrow aspirate showed 90% of Sudan black– and chloroacetate esterase–positive blasts with Auer rods. Immunophenotype was positive for MPO, CD13, CD33, CD38, C-KIT, CD11C, and CD15 antigens. The karyotype was 45, X,−Y, t(10;11)(q23;p15) [15]/46, XY[5]. Because of the lack of material, cytogenetic and/or molecular studies at diagnosis or at first relapse could not be performed, and therefore it could not be established whether the AML bearing the translocation in this case was a second disease induced by previous treatments instead of a second late relapse. All investigations were performed with approval, IRB 00004918.

Fluorescent in situ hybridization

Initial fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis was performed using the RP5-1173K1 DNA clone spanning exons 10 to 20 of NUP98 as described previously.19 Based on molecular findings, we selected the RP11-469M1 clone for 10q23.3/HHEX and set up a double-color double-fusion FISH assay for confirmation.

Breakpoint cloning

Molecular studies were carried out with total RNA extracted by TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) from the patient's cryopreserved bone marrow cells. Total RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed using 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA end (RACE) kit (Invitrogen). cDNA was amplified using NUP_769_787F as a NUP98 gene-specific primer and AUAP (abridged universal amplification primer; Invitrogen). A seminested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using NUP_1083_1106F (exon 8) as a NUP98-specific primer and AUAP primer (Invitrogen). PCR was performed using Expand extralong PCR system (Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). The PCR product was subcloned into the pGEM-T easy (Promega, Madison, WI) following the manufacturer's instructions and inserts were sequenced. Sequence analysis was performed using the Blast sequences program (NCBI, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/)20 and BLAT Search Genome (http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgBlat).21 Numbering of the primers refers to GenBank entries NM_139131.1 (NUP98) and NM_002729.2 (HHEX).22

Total RNA (1 μg) isolated from the patient's leukemic blasts was reverse transcribed for reverse-transcription (RT)–PCR experiments using thermoscript RT-PCR System (Invitrogen). The NUP98/HHEX fusion transcript was detected using NUP_1284_1303F (exon 10) and HHEX_606_587R (exon 3) primers and reciprocal HHEX/NUP98 using primers HHEX_346F (exon 1) and NUP1861_1843R (exon 14). The PCR products were cloned in pGEM-T easy vector (Promega) and sequenced. The genomic characterization of breakpoints was performed by PCR using NUP_in13_3213F (5′-GGATTACAGGTGCACGCTTC-3′ intron 13) and HHEX_496_477R (exon 2) and the PCR products were sequenced.

Construction of recombinant plasmids and retroviral vectors

Starting from a KpnI-ApaI cDNA fragment cloned from the patient's cells covering the fusion breakpoint, full-length clones were generated by adding the 5′ end from NUP98 (BssHII-KpnI from L3-HA-NUP98; kindly provided by B. Felber, National Institutes of Health [NIH]) and the 3′ end of HHEX (ApaI-SacI from pBKS-HHEX1; kindly provided by G. Manfioletti, University of Trieste, Trieste, Italy). To generate NUP98/HHEX-ΔGLFG, a 687-bp SpeI fragment in NUP98 (384-1072, NM_139131) was removed. NUP98/HHEX-ΔHD was generated by standard PCR removing 205 bp (474-679, HHEX, NM_002729). The NUP98/HHEX-ΔCTD mutant was made by removing a 114-bp BclI fragment in the C-terminus. Further, NUP98/HHEX GLFG mutants (1-3, 4-5, 6-9, 1-3 + 6-9) were all generated by PCR (primers available upon request). All PCR-generated fragments were fully verified by sequencing. An N-terminal FLAG-tag was added using standard PCR cloning. FLAG-NUP98/HHEX wild type and mutants were cloned into pcDNA3 and pMSCV-IRES/YFP. N-terminal EGFP fusions were generated by cloning into pEGFP-C (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). pMSCV-NUP98/HOXA9-IRES-EGFP was kindly provided by D. G. Gilliland, Harvard Medical School (Boston, MA).23

Bone marrow infections and transplantation

Generally, all procedures were performed as described previously.24 In brief, bone marrow was harvested from Balb/C mice previously treated with 150 mg 5-fluorouracil/kg for 4 days. The cells were stimulated for 24 hours in RPMI supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 ng/mL human interleukin-6, 6 ng/mL murine interleukin-3, and 100 ng/mL murine stem cell factor (PeproTech EC, London, United Kingdom). High-titer retrovirus supernatants were produced by transient cotransfection of HEK293T cells with a packaging vector (pIK6). Virus-containing supernatants were collected after 48 hours and concentrated.25 For infection, the cells were spinoculated at 1124g for 90 minutes at 37°C with an estimated multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 to 10:1. IL-3–dependent cell lines from NUP98/HOXA9- or NUP98/HHEX-infected bone marrow cells were established in vitro directly after fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)–assisted sorting in RPMI/10% FBS with IL-3 alone (6 ng/mL).

Transduced bone marrow cells (1-1.5 × 106) were injected into the tail vein of lethally irradiated (137Cs, 9 gy) syngenic recipients. Sublethally irradiated (4.5 gy) secondary transplants were injected with 2 × 106 bone marrow cells from a primary diseased mouse. For peripheral blood and bone marrow cell FACS analysis, single-cell suspensions were stained with the following monoclonal antibodies: phycoerythrin-labeled c-Kit, Sca-1, Ter119, Gr-1, Mac-1, CD4, and CD8 and APC-labeled B220 (all from Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Morphologic analysis of peripheral blood, bone marrow, and spleen cells and histologic analysis were performed using standard procedures. Images were visualized under a Zeiss Axio (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) microscope equipped with Plan Neo Fluor 40× (Figure 6) or 100× (Figure 2) objective lenses. Images were captured with a AxioCam (Carl Zeiss) and processed with Adobe Photoshop 7.0 software (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

In vitro clonogenic progenitor assay (serial replating)

Infected bone marrow cells were plated (104) in 1 mL methylcellulose culture (Methocult M3434; StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC), containing IL-3, IL-6, mSCF, and hEPO. Colonies were scored microscopically after 8 to 10 days, then harvested and replated (104) in the same way for up to 4 rounds.

Myeloid differentiation assays

Myeloid progenitors (105) were washed twice in PBS to remove cytokine from the medium. Cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640, 10% FBS, 1% Pen/Strep with addition of the appropriate cytokine (0.5 ng/mL granulocyte colony-stimulating factor [G-CSF], 1 ng/mL granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor [GM-CSF], 1 ng/mL IL-3; all from PeproTech EC). Cells were kept in culture 21 for days, and the cell number was scored every second day. Cellular differentiation was examined by Wright-Giemsa staining following 72 hours of culture in G-CSF following 8 days of culture in GM-CSF.

FL stimulation in vitro

Cellular growth was assessed in medium (10% FBS in RPMI 1640 supplemented with cytokines [IL-3, IL-6, mSCF]) with or without murine Flt3 ligand (FL; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) in presence or absence of a Flt3 inhibitor (Calbiochem, San Jose, CA) at 10 μM. Cells were washed 3 times in PBS before plating in specified concentrations of FL-supplied media.

Immunofluorescence

HeLa and NIH-3T3 or COS-1 cells were transfected with the following pEGFP-NUP98/HHEX wild type and mutants, as well as with EGFP-NUP98, EGFP-HHEX, or EGFP-NUP98/HOXA9, and seeded on coverslips 24 hours after transfection. After another 24 hours, the cells were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes on ice and washed 3 times with PBS. The cells were examined with an Olympus (Tokyo, Japan) IX50 microscope equipped for immunofluorescence (original magnification 100×).

Transcriptional activation assay

For transient transfection assays, K562 cells were transferred to 0.4-cm electroporation cuvettes at a density of 107 cells in 200 μL medium. The cells and 5 μg of the luciferase reporter plasmid and 5 μg of the β-galactosidase reporter plasmid were mixed and electroporated at 250 V, 975 μF. In repression experiments, the cells were cotransfected with either pMUG1 vector or the pMUG1-Myc-PRH series of plasmids. Electroporated cells were incubated for 24 hours before harvest by centrifugation and measuring luciferase activity using the Promega Luciferase Assay System according to the manufacturer's instructions. A β-galactosidase assay was performed as an internal control for transfection efficiency: 40 μL cell lysate was mixed with 900 μL Z buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol) and 200 μL ONPG (4 mg/mL) and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. The reaction was stopped by addition of 1 M Na2CO3 (200 μL) and the absorbance measured at 420 nm. After subtraction of the background, the luciferase counts were normalized against the β-galactosidase value.

Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed (400 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton, 0.1 M HEPES, pH 7.5). Cleared lysates were loaded onto 8% Bis-Tris polyacrylamide gel and blotted to a nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA). A monoclonal anti-GFP antibody (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) and a goat horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti–mouse immunoglobulin antibody (Biorad, Hercules, CA) were then used. Protein expression was detected with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) Western blotting detection reagents (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom).

Southern blot analysis

High-molecular-weight DNA was extracted from leukemic blasts from the bone marrow of diseased mice. Samples consisting of 10 μg genomic DNA were subjected to restriction endonuclease digestion (EcoRI), agarose gel electrophoresis, Southern blot transfer, and hybridization (with an EYFP cDNA probe) as described previously.24

Retroviral integration cloning

Viral integration sites in NUP98/HHEX leukemic blasts were cloned using a splinkerette PCR protocol as described previously.26 PCR products were separated on a 2% agarose gel, purified, and sequenced directly using the ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator version 3.1 Cycle Sequencing kit (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA).

Gene-expression profiling

In 3 independent experiments, bone marrow cells were transduced with MSCV-IRES-EGFP/YFP expressing NUP98/HOXA9 or NUP98/HHEX. Seventy-two hours after transduction, EGFP/EYFP-positive cells were FACS-sorted and RNA was isolated by ion-exchange chromatography with RNAmini (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Target preparation and hybridization of microarrays was conducted as described in the Affymetrix GeneChip Expression Analysis Technical Manual (http://www.affymetrix.com).27 Briefly, total RNA was converted to first-stranded cDNA, using Superscript II reverse transcriptase primed by poly(T) oligomer that incorporated the T7 promoter. Second-strand cDNA synthesis was followed by in vitro transcription for linear amplification of each transcript and incorporation of CTP and UTP. The cRNA products were fragmented to 200 nucleotides or less, heated at 99°C for 5 minutes, and hybridized onto mouse genome 430A 2.0 expression array for 16 hours at 45°C to the microarrays. Posthybridization staining and washing were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Fluorescence was amplified by adding biotinylated antistreptavidin and an additional aliquot of streptavidin-phycoerythrin stain. A confocal scanner was used to collect fluorescence signal at 3-mm resolution after excitation at 570 nm. The average signal from 2 sequential scans was calculated for each microarray feature. Gene expression data were normalized using the vsn algorithm. Univariate anova models were fitted gene-by-gene, and genes were considered significant whenever the fold change was superior to 1.5 and P less than .05. All statistical analysis was performed using the R-statistical software (version 2.4.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

PCR analysis

Target validation was performed in triplicates by quantitative real-time PCR (SyBRgreen, on an ABI prism 7700 sequence detection system; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). For each target, the results were normalized to Gapdh and given as ΔΔCt values normalized to MOCK-infected (MSCV-IRES-EGFP) bone marrow cells. Further primer information is given in Table S1 (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Second, VDJ rearrangements of the immunoglobulin heavy chain in the NUP98/HHEX leukemic blasts from mice that underwent transplantation were determined by PCR using 2 upstream degenerate primers (DFS, DQ52) and one reverse primer (JH4). All 3 primers were used in a single reaction to detect rearrangements from DJH1 to DJH4 as described previously.28

The data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/)29 and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE10909.

Results

Cytogenetic analysis in 2002 revealed a t(10;11)(q23;p15) in bone marrow blasts from a patient with AML (FAB-M2) (Figure 1A). Fluorescent in situ hybridization with the 11p15 probe (RP5-1173K1) gave 3 hybridization signals on normal 11, der(11), and der(10), indicating a disruption of the NUP98 gene by this translocation (not shown). RACE-PCR analysis showed the presence of an in-frame fusion of nucleotide 1718 (exon 13, NM 139131.1) of NUP98 and nucleotide 426 (exon 2, NM 002729.2) of the human hematopoietic homeobox gene (HHEX) resulting in a NUP98/HHEX fusion (Figure 1B). Expression of this fusion in the patient's blast cells was further confirmed by RT-PCR. Three different in-frame spliced transcripts between NUP98 (exon 13) and HHEX (exon 2) were found (clones 3, 13, and 20). A detailed map of the 3 NUP98/HHEX isoforms is provided in Figure S1. A reciprocal out-of-frame chimeric product joining nucleotide 393 (exon 1) of HHEX and nucleotide 1719 (exon 14) of NUP98 was also found. At the genomic level, a fusion between intron13 of NUP98 and nucleotide 418 (exon 2) of HHEX was detected (Figure 1B). Splicing of the primary transcript eliminates intron13 of NUP98 and 8 nucleotides of HHEX joining nucleotide 1718 (exon 13) of NUP98 and nucleotide 426 (exon 2) of HHEX (Figure 1B). The presence of the NUP98/HHEX fusion was further confirmed by double-color double-fusion FISH assay using the RP5-1173K1 DNA clone spanning exons 10 to 20 of NUP98 and RP11-469M1 clone for 10q23.3/HHEX (Figure 1C).

t(10;11)(q23;p15) results in a NUP98/HHEX fusion gene. (A) The G-banded karyotype is 45, X,−Y, t(10;11)(q23;p15)[15]/46, XY[5]. The arrows indicate the reciprocal chromosome translocations. (B) RACE-PCR and genomic characterization: NUP98 and HHEX are fused in-frame, joining nucleotide 1718 (exon 13) of NUP98 to nucleotide 426 (exon 2) of HHEX. Genomic breakpoint occurs inside the intron 13 in NUP98 gene and inside the exon 2 in HHEX gene joining intron 13 of NUP98 to exon 2 of HHEX (nucleotide 418). (C) Double-color double-fusion FISH assay. RP5-1173K1 (red) and RP11-469M1 (green) give a red signal on normal 11, a green signal on normal 10, and a red/green signal on both der(11) and der(10) (arrows).

t(10;11)(q23;p15) results in a NUP98/HHEX fusion gene. (A) The G-banded karyotype is 45, X,−Y, t(10;11)(q23;p15)[15]/46, XY[5]. The arrows indicate the reciprocal chromosome translocations. (B) RACE-PCR and genomic characterization: NUP98 and HHEX are fused in-frame, joining nucleotide 1718 (exon 13) of NUP98 to nucleotide 426 (exon 2) of HHEX. Genomic breakpoint occurs inside the intron 13 in NUP98 gene and inside the exon 2 in HHEX gene joining intron 13 of NUP98 to exon 2 of HHEX (nucleotide 418). (C) Double-color double-fusion FISH assay. RP5-1173K1 (red) and RP11-469M1 (green) give a red signal on normal 11, a green signal on normal 10, and a red/green signal on both der(11) and der(10) (arrows).

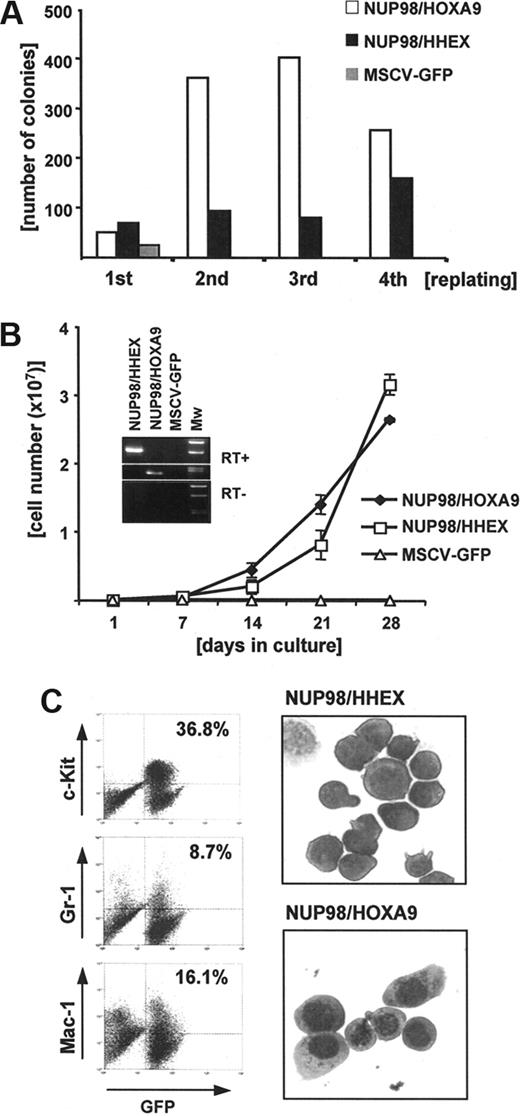

To functionally characterize this new NUP98/HHEX fusion the full-length cDNA was cloned into retroviral expression vectors. The best characterized fusion gene involving NUP98 is the NUP98/HOXA9 fusion resulting from t(7;11)(p15; p15).6-8 Therefore, we first compared in vitro transforming potential of NUP98/HHEX with NUP98/HOXA9 in serial replating assays in semisolid medium as well as in liquid cultures. As shown in Figure 2A, expression of NUP98/HHEX in primary murine bone marrow cells results in aberrant self-renewal as shown by colony formation over 4 consecutive platings. This analysis was performed with all 3 NUP98/HHEX isoforms (clones 3, 13, 20), but no significant differences were observed (data not shown). However, in contrast to NUP98/HOXA9, significantly lower numbers of NUP98/HHEX-containing colonies were seen. Culturing of cells expressing either NUP98/HHEX or NUP98/HOXA9 in liquid medium over several weeks allowed the generation of cell lines stably expressing the fusion genes (Figure 2B). Immunophenotypic analysis characterized these cells as early myeloid progenitor cells (KIT/high, GR1-Mac1/low) with a typical blastlike morphology (Figure 2C). Optimal cellular growth required the presence of growth factors (IL-3, SCF, IL-6). Growth was significantly reduced in medium containing only IL-3 and removal of cytokines results in rapid cell death (not shown). Interestingly, NUP98/HHEX-expressing cells grown in the presence of G-CSF were able to differentiate into mature granulocytes, while IL-3 alone was sufficient for the growth of immature NUP98/HHEX cells (not shown). These data demonstrate that NUP98/HHEX transforms primary bone marrow progenitor cells by blocking normal myeloid differentiation and providing aberrant self-renewal.

Expression of NUP98/HHEX in murine bone marrow progenitors results in enhanced self-renewal and immortalization in vitro. (A) Representative (of 5 independent experiments) assay showing increasing number of colonies with successive replating for cells retrovirally expressing NUP98/HHEX or NUP98/HOXA9 and a rapid decline in bone marrow transduced with the empty pMSCV-IRES-EGFP vector. (B) NUP98/HHEX expression results in expansion of transduced (EYFP+) cells in IL-3–, IL-6–, and mSCF-containing medium. The insert confirms mRNA expression of the fusion as assessed by RT-PCR using primers covering the breakpoints. Error bars represent SD from 3 independent experiments. (C) Immunophenotype of bone marrow cells from liquid cultures. Representative Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospin preparation of NUP98/HHEX- or NUP98/HOXA9-transduced bone marrow, cultured for 3 weeks in the presence of IL-3.

Expression of NUP98/HHEX in murine bone marrow progenitors results in enhanced self-renewal and immortalization in vitro. (A) Representative (of 5 independent experiments) assay showing increasing number of colonies with successive replating for cells retrovirally expressing NUP98/HHEX or NUP98/HOXA9 and a rapid decline in bone marrow transduced with the empty pMSCV-IRES-EGFP vector. (B) NUP98/HHEX expression results in expansion of transduced (EYFP+) cells in IL-3–, IL-6–, and mSCF-containing medium. The insert confirms mRNA expression of the fusion as assessed by RT-PCR using primers covering the breakpoints. Error bars represent SD from 3 independent experiments. (C) Immunophenotype of bone marrow cells from liquid cultures. Representative Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospin preparation of NUP98/HHEX- or NUP98/HOXA9-transduced bone marrow, cultured for 3 weeks in the presence of IL-3.

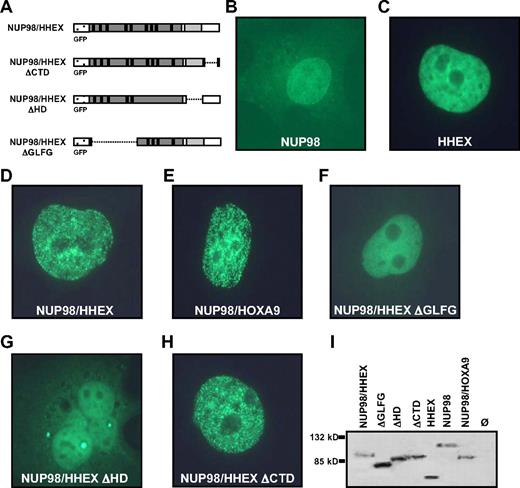

The NUP98/HHEX fusion includes the GLEBS domain and 9 GLFG repeats of NUP98 fused to the homeodomain of HHEX. To determine the requirements for transformation, a series of mutants lacking the 5 proximal GFLG repeats and the GLEBS domain (ΔGLFG) in the NUP98 part, lacking the homeodomain (ΔHD) or the C-terminal domain (ΔCTD) of HHEX were generated (Figure 3A). To determine their cellular localization, the mutants were fused to an N-terminal EGFP tag. The localization of NUP98/HHEX was compared with NUP98 and HHEX localization upon transient transfection in HeLa, NIH-3T3, and COS-1 cells. As demonstrated previously, and shown in Figure 3B, accentuated signals of NUP98 were found in the nucleus and toward the nuclear membrane of HeLa cells.30 Fluorescent signals of EGFP-HHEX were exclusively found in the nucleus but were absent from nucleolar region (Figure 3C). Although the NUP98/HHEX is also localized in the nucleus, the protein may be accumulated in nuclear subdomains resulting in a finely speckled appearance (Figure 3D). An identical immunolocalization pattern was observed upon transfection of NUP98/HOXA9 (Figure 3E). The fluorescence signal of the NUP98/HHEX-ΔCTD mutant was similar to that of the NUP98/HHEX protein (Figure 3D,H), however no “microspeckled” pattern was observed upon expression of NUP98/HHEX-ΔGLFG or -ΔHD mutants (Figure 3F,G). Expression of the EFGP fusion proteins was further confirmed by immunoblotting (Figure 3I). Identical localization patterns were observed in NIH-3T3 and COS-1 cells (data not shown). These experiments demonstrate a highly similar nuclear localization pattern of the NUP8/HHEX and NUP98/HOXA9 fusion proteins. Furthermore, they show that the microspeckled fluorescence signal shown by NUP98/HHEX was dependent on the presence of the NUP98 GFLG repeats as well as the HHEX homeodomain.

Cellular localization of wild-type (WT) and mutant forms of the NUP98/HHEX fusion protein. (A) Schematic representation of N-terminal EGFP-tagged NUP98/HHEX expression constructs. (B-H) Localization of EGFP-tagged proteins upon transient transfection in HeLa cells. (I) Immunoblot of expressed proteins as detected by anti-GFP antibodies.

Cellular localization of wild-type (WT) and mutant forms of the NUP98/HHEX fusion protein. (A) Schematic representation of N-terminal EGFP-tagged NUP98/HHEX expression constructs. (B-H) Localization of EGFP-tagged proteins upon transient transfection in HeLa cells. (I) Immunoblot of expressed proteins as detected by anti-GFP antibodies.

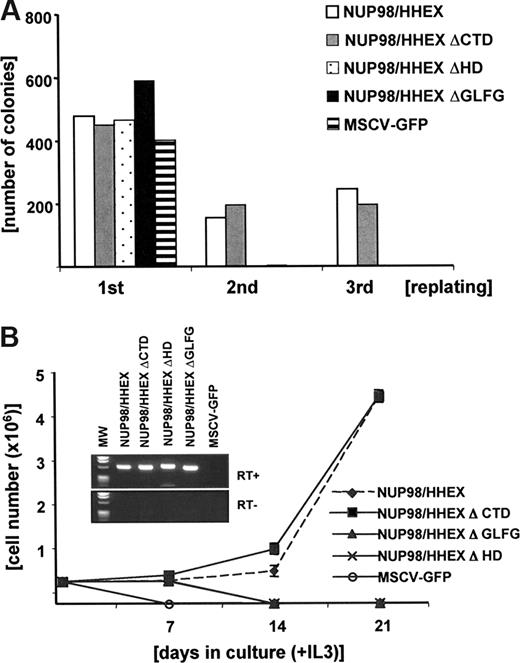

To analyze the functional contribution of these domains, we examined NUP98/HHEX mutants in a serial replating assay. As shown in Figure 4A, no colonies were formed in the second replating in cells expressing either NUP98/HHEX-ΔGLFG or -ΔHD, whereas cells expressing NUP98/HHEX-ΔCTD, as well as the full-length fusion, were successfully replated. Likewise, no stable cell lines could be generated in liquid cultures from cells expressing NUP98/HHEX-ΔGLFG or -ΔHD (data not shown). Like NUP98/HHEX (wild type), expression of the NUP98/HHEX-ΔCTD mutant allowed growth in medium containing IL-3, IL-6, SCF, or IL-3 only with an almost identical immunophenotype (KIT/high, GR1-Mac1/low) (Figure 4B and data not shown). Expression of the appropriate fusion was further confirmed by RT-PCR. These data show that in vitro transformation of primary bone marrow cells by NUP98/HHEX is dependent on the NUP98-GFLG repeats as well as the HHEX homeodomain. The NUP98 moiety in NUP98/HHEX contains 9 GFLG repeats and the GLEBS domain.31 To further dissect their role, we generated a series of mutants lacking GFLG repeats 1 to 3, 4 to 5, 6 to 9, 1 to 3 and 6 to 9, and 4 to 9 in presence of the GLEBS domain (Figure S2A). In contrast to the full-length NUP98/HHEX fusion, expression of any of these fusions did not result in any significant replating after the third round, suggesting that integrity of the NUP98 moiety is critical for providing aberrant self-renewal capacity by NUP98/HHEX (Figure S2B).

The GFLG repeats as well as the homeodomain (HD) are essential for in vitro transformation by the NUP98/HHEX fusion gene. (A) Representative replating assay (of 3 independent experiments) of bone marrow cells transduced with NUP98/HHEX (WT) and NUP98/HHEX deletion mutants. (B) Growth curve of bone marrow cells transduced with NUP98/HHEX (WT) and NUP98/HHEX deletion mutants grown in IL-3.

The GFLG repeats as well as the homeodomain (HD) are essential for in vitro transformation by the NUP98/HHEX fusion gene. (A) Representative replating assay (of 3 independent experiments) of bone marrow cells transduced with NUP98/HHEX (WT) and NUP98/HHEX deletion mutants. (B) Growth curve of bone marrow cells transduced with NUP98/HHEX (WT) and NUP98/HHEX deletion mutants grown in IL-3.

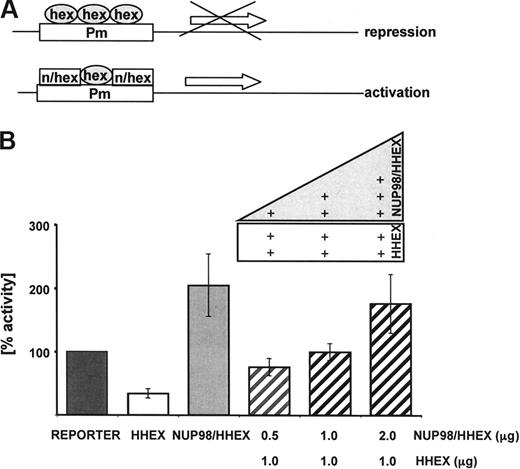

HHEX was previously shown to be an essential regulator of early hematopoiesis predominately acting as a transcriptional repressor.32-34 In the leukemia-associated fusion gene, the N-terminal HHEX transrepression domain is replaced with the NUP98 GLFG repeats that have transactivation potential,13 suggesting a potential shift from a transcriptional repressor to a transcriptional activator. To test this hypothesis, a series of transcriptional reporter assays were performed. Previous experiments have shown that expression of HHEX was able to repress expression of luciferase-reporter (Figure 5A) driven by a promoter that harbors 5 HHEX-binding sites (-CAATTAAA-).33,34 As shown in Figure 5B, in contrast to HHEX, expression of the NUP98/HHEX fusion results in a significant increase of reporter expression. Furthermore, coexpression of HHEX with increasing amounts of NUP98/HHEX was able to block repression by HHEX and resulted in activation of the reporter in a transdominant fashion. These data suggest that NUP98/HHEX might be able to activate genes repressed by HHEX.

Transcriptional activity of the NUP98/HHEX fusion gene as shown by luciferase assays. (A) A luciferase reporter gene under the control of a promoter with 5 consecutive HHEX-binding sites was cotransfected into K562 cells with expression construct encoding NUP98/HHEX. (B) Coexpression of HHEX (1 μg) with increasing amounts of NUP98/HHEX (0.5-2 μg) reverted transcriptional repression mediated by HHEX into activation. Luciferase activity was corrected for transfection efficiency based on the activity of a cotransfected β-galactosidase construct. The transcriptional activating potential is expressed as the fold induction relative to the control. Bars represent the mean plus or minus SD of 3 independent experiments.

Transcriptional activity of the NUP98/HHEX fusion gene as shown by luciferase assays. (A) A luciferase reporter gene under the control of a promoter with 5 consecutive HHEX-binding sites was cotransfected into K562 cells with expression construct encoding NUP98/HHEX. (B) Coexpression of HHEX (1 μg) with increasing amounts of NUP98/HHEX (0.5-2 μg) reverted transcriptional repression mediated by HHEX into activation. Luciferase activity was corrected for transfection efficiency based on the activity of a cotransfected β-galactosidase construct. The transcriptional activating potential is expressed as the fold induction relative to the control. Bars represent the mean plus or minus SD of 3 independent experiments.

To determine the in vivo transforming activity of NUP98/HHEX, series of bone marrow transplantation experiments were performed. Lethally irradiated syngeneic mice (Balb/C) were reconstituted with 1.0 to 1.5 × 106 bone marrow cells containing 10% to 15% NUP98/HHEX (EYFP+) cells. All mice (of 2 independent experiments) developed an acute leukemia phenotype after a long latency of approximately 9 months, whereas the control mice infected with an empty virus (MSCV-IRES-EGFP) never developed any signs of disease within 15 months after transplantation (Figure 6A). The NUP98/HHEX-induced leukemia is characterized by high white blood cell counts (150-250 × 109/L [15-25 × 107/mL]), hepatosplenomegaly (spleen: 390-440 mg; liver 1200-1340 mg), lymphadenopathy, and extensive bone marrow and organ infiltration (Figure 6B). Immunophenotyping of the bone marrow cells demonstrated the presence of NUP98/HHEX (EYFP+) immature (KIT+) cells expressing B-cell (B220+) and/or myeloid (Mac1/GR1+) surface markers with a blastlike morphology (Figure 6C). Expression of the fusion was further confirmed by RT-PCR analysis in diseased tissues (Figure 6D). Isolated cells from diseased animals were easily propagated in liquid cultures containing IL-3 over several weeks (data not shown). A similar acute leukemia syndrome can be induced after 12 to 15 weeks by transplant of 106 leukemic blasts into sublethally irradiated (4.5 gy) secondary hosts (Figure 6A). Interestingly, bone marrow cells from the secondary transplants were characterized by an increase in B220+ cells. However, a high percentage of cells also expressed B220 and Mac1/GR1 (not shown). PCR-based IgH rearrangement analysis showed DJH rearrangements in blasts from 4 animals (Figure S3), suggesting that some of the NUP98/HHEX-expressing blasts have the potential for maturation to the B-cell lineage. The NUP98/HHEX-induced leukemia has clonal character as shown by viral integration analysis using Southern blotting (Figure 6E). A splinkerette-PCR approach was chosen to directly clone the viral integration sites in NUP98/HHEX leukemia from 4 mice. As shown in Figure 6F, in 3 of 4 mice, only a single integration site found was found, whereas 2 integrations occurred in one animal further demonstrating the clonal character of the disease. All integration sites were different. Among them is the EVI1/MDS1 locus known to play an important role in the biology of murine and human hematologic malignancies.2 This dataset suggests that expression of NUP98/HHEX is essential but not sufficient for induction of an acute leukemic phenotype.

Expression of NUP98/HHEX induces acute leukemia in mice. (A) Kaplan-Meier plot of primary recipients that received a transplant of NUP98/HHEX-transduced bone marrow cells (solid line, n = 10 average latency [285 ± 15 days]. Secondary recipients (dashed line, n = 10) succumbed to the disease with reduced latency (100 ± 20 days). Bone marrow transplantations have been done in 2 independent series. (B) Histology of representative primary mouse demonstrated the presence of leukemic blasts in blood smears and extensive leukemia tissue infiltration of organs including the spleen, liver, and lymph nodes. (C) Immunophenotyping of leukemic cells. Flow cytometric profiles of bone marrow–derived blasts of a representative NUP98/HHEX leukemia mouse. Infected cells are identified by EYFP+ fluorescence. (D) Expression of NUP98/HHEX fusion in spleen, bone marrow, and peripheral blood of 2 representative diseased mice was analyzed by RT-PCR analysis. (E) Viral integration analysis by Southern blotting of EcoRI-digested genomic DNA probed with an EYFP probe shows the clonal character of the disease. (F) Retroviral insertion sites in leukemic blasts from 4 mice with NUP98/HHEX-induced disease that underwent transplantation. Insertions were cloned using a splinkerette-PCR approach.

Expression of NUP98/HHEX induces acute leukemia in mice. (A) Kaplan-Meier plot of primary recipients that received a transplant of NUP98/HHEX-transduced bone marrow cells (solid line, n = 10 average latency [285 ± 15 days]. Secondary recipients (dashed line, n = 10) succumbed to the disease with reduced latency (100 ± 20 days). Bone marrow transplantations have been done in 2 independent series. (B) Histology of representative primary mouse demonstrated the presence of leukemic blasts in blood smears and extensive leukemia tissue infiltration of organs including the spleen, liver, and lymph nodes. (C) Immunophenotyping of leukemic cells. Flow cytometric profiles of bone marrow–derived blasts of a representative NUP98/HHEX leukemia mouse. Infected cells are identified by EYFP+ fluorescence. (D) Expression of NUP98/HHEX fusion in spleen, bone marrow, and peripheral blood of 2 representative diseased mice was analyzed by RT-PCR analysis. (E) Viral integration analysis by Southern blotting of EcoRI-digested genomic DNA probed with an EYFP probe shows the clonal character of the disease. (F) Retroviral insertion sites in leukemic blasts from 4 mice with NUP98/HHEX-induced disease that underwent transplantation. Insertions were cloned using a splinkerette-PCR approach.

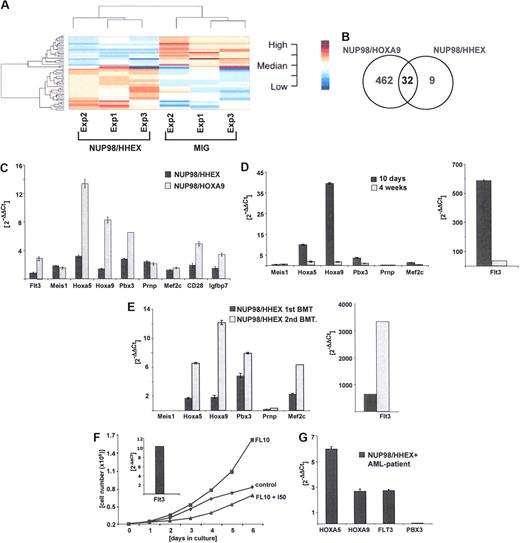

Thus, the new NUP98/HHEX fusion has in vitro and in vivo transforming activity, presumably by activating a gene expression program that blocks early differentiation and causes aberrant self-renewal. To obtain better insights into NUP98/HHEX, and NUP98-homedomain fusion mediated transformation, we determined possible downstream targets by comparative gene expression profiling. As attempts to generate murine bone marrow cells conditionally expressing NUP98-homodomain fusions failed (not shown), we transiently expressed NUP98/HHEX and NUP98/HOXA9 in murine bone marrow cells and determined regulated targets in cells expressing the respective fusion and GFP 72 hours after infection. As shown in Figure 7A (Tables S2,S3), a significant number of genes were up- or down-regulated upon expression of NUP98/HHEX or NUP98/HOXA9 compared with mock (pMSCV-IRES-EGFP)–infected cells. We found 32 genes to be up- or down-regulated by both NUP98/HHEX and NUP98/HOXA9 fusion genes (Figure 7B; Table 1). We next validated a number of genes that are targeted by more than one NUP98/HD fusion by quantitative PCR analysis. As shown in Figure 7C, Hoxa5, Hoxa9, Prnp, Pbx3, Mef2c, Flt3, Meis1, Cd28, MIgh6, and Igfbp7 were all up-regulated by NUP98/HOXA9 and to a lesser degree also by NUP98/HHEX. Both Flt3 and Meis1 were scored under the cutoff level of 1.5-fold (compared with mock infection) in the array-based analysis, although both were found up-regulated by quantitative RT-PCR. As this initial analysis was limited to 72 hours after infection, we further followed expression of these target genes over a longer period of time and compared them 10 days and 4 weeks after transduction (Figure 7D). For further validation, we have determined the expression levels of several of these presumptive targets (Flt3, Hoxa5, Hoxa9, Pbx3) in leukemic blasts from NUP98/HHEX mice that underwent primary or secondary transplantation (Figure 7E). Interestingly, compared with the in vitro immortalized bone marrow cells, leukemic blasts expressed very high levels of Flt3 in 2 of 4 NUP98/HHEX leukemias analyzed. High levels of Flt3 mRNA expression resulted in a significant growth advantage upon addition of Flt3 ligand (FL) (Figure 7F). Finally, we have compared the expression levels of some of these genes in blasts from the index AML patient carrying the t(10;11)(q23;p15) that leads to the NUP98/HHEX fusion. In these blasts, deregulated expression of Hoxa5, Hoxa9, and Flt3 but not Pbx3 was observed (Figure 7G). Taken together, this set of data demonstrates that NUP98/HHEX leads to deregulation of a number of target genes that are also targeted by NUP98/HOXA9 not only in the mouse model, but also in the human NUP98/HHEX leukemia.

Identification and validation of putative NUP98/HHEX target genes by comparative gene expression profiling. (A) Gene expression signature of bone marrow progenitors cells 72 hours after retroviral transduction expressing NUP98/HHEX in unsupervised analysis using hierarchic clustering method. (B) Venn diagram analysis of numbers of genes found to be regulated by NUP98/HOXA9 (left), NUP98/HHEX (right), or both fusion genes (middle). (C) Quantitative RT-PCR (Q-PCR)–based validation of genes regulated by NUP98/HOXA9 and NUP98/HHEX in murine bone marrow cells 72 hours after transduction. (D) Expression of selected putative targets in NUP98/HHEX-expressing murine bone marrow cells after 10 days (▬) or 4 weeks ( ) of culture in medium containing IL-3, IL-6, and SCF (Q-PCR analysis). (E) Expression of selected putative NUP98/HHEX target genes in leukemic blasts from primary (▬) and secondary (

) of culture in medium containing IL-3, IL-6, and SCF (Q-PCR analysis). (E) Expression of selected putative NUP98/HHEX target genes in leukemic blasts from primary (▬) and secondary ( ) transplantations. Note the excessive levels of Flt3 mRNA expression in NUP98/HHEX blasts (right panel). (F) In vitro growth curve where bone marrow cells harvested from diseased NUP98/HHEX mouse were grown in 10% FBS and 50 ng/mL FL in the presence or absence of 10 μM Flt3 inhibitor for a period of 6 days. The insert shows a high level of expression of Flt3 mRNA in analyzed cells prior to the addition of Flt3 inhibitor. (G) Expression of HOXA5, HOXA9, FLT3, and PBX3 in blasts from a patient with t(10;11)(q23;p15) and NUP98/HHEX. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis normalized to the levels observed in cord blood mononuclear cells from 2 healthy donors. Bars represent the variance from 3 independent experiments.

) transplantations. Note the excessive levels of Flt3 mRNA expression in NUP98/HHEX blasts (right panel). (F) In vitro growth curve where bone marrow cells harvested from diseased NUP98/HHEX mouse were grown in 10% FBS and 50 ng/mL FL in the presence or absence of 10 μM Flt3 inhibitor for a period of 6 days. The insert shows a high level of expression of Flt3 mRNA in analyzed cells prior to the addition of Flt3 inhibitor. (G) Expression of HOXA5, HOXA9, FLT3, and PBX3 in blasts from a patient with t(10;11)(q23;p15) and NUP98/HHEX. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis normalized to the levels observed in cord blood mononuclear cells from 2 healthy donors. Bars represent the variance from 3 independent experiments.

Identification and validation of putative NUP98/HHEX target genes by comparative gene expression profiling. (A) Gene expression signature of bone marrow progenitors cells 72 hours after retroviral transduction expressing NUP98/HHEX in unsupervised analysis using hierarchic clustering method. (B) Venn diagram analysis of numbers of genes found to be regulated by NUP98/HOXA9 (left), NUP98/HHEX (right), or both fusion genes (middle). (C) Quantitative RT-PCR (Q-PCR)–based validation of genes regulated by NUP98/HOXA9 and NUP98/HHEX in murine bone marrow cells 72 hours after transduction. (D) Expression of selected putative targets in NUP98/HHEX-expressing murine bone marrow cells after 10 days (▬) or 4 weeks ( ) of culture in medium containing IL-3, IL-6, and SCF (Q-PCR analysis). (E) Expression of selected putative NUP98/HHEX target genes in leukemic blasts from primary (▬) and secondary (

) of culture in medium containing IL-3, IL-6, and SCF (Q-PCR analysis). (E) Expression of selected putative NUP98/HHEX target genes in leukemic blasts from primary (▬) and secondary ( ) transplantations. Note the excessive levels of Flt3 mRNA expression in NUP98/HHEX blasts (right panel). (F) In vitro growth curve where bone marrow cells harvested from diseased NUP98/HHEX mouse were grown in 10% FBS and 50 ng/mL FL in the presence or absence of 10 μM Flt3 inhibitor for a period of 6 days. The insert shows a high level of expression of Flt3 mRNA in analyzed cells prior to the addition of Flt3 inhibitor. (G) Expression of HOXA5, HOXA9, FLT3, and PBX3 in blasts from a patient with t(10;11)(q23;p15) and NUP98/HHEX. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis normalized to the levels observed in cord blood mononuclear cells from 2 healthy donors. Bars represent the variance from 3 independent experiments.

) transplantations. Note the excessive levels of Flt3 mRNA expression in NUP98/HHEX blasts (right panel). (F) In vitro growth curve where bone marrow cells harvested from diseased NUP98/HHEX mouse were grown in 10% FBS and 50 ng/mL FL in the presence or absence of 10 μM Flt3 inhibitor for a period of 6 days. The insert shows a high level of expression of Flt3 mRNA in analyzed cells prior to the addition of Flt3 inhibitor. (G) Expression of HOXA5, HOXA9, FLT3, and PBX3 in blasts from a patient with t(10;11)(q23;p15) and NUP98/HHEX. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis normalized to the levels observed in cord blood mononuclear cells from 2 healthy donors. Bars represent the variance from 3 independent experiments.

Up- or down-regulated genes by both the NUP98/HHEX and the NUP98/HOXA9 fusions in primary murine bone marrow cells

| Gene name . | Fold change* . | |

|---|---|---|

| NUP98/HOXA9 . | NUP98/HHEX . | |

| Prion protein (Prnp) | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| Carbonic anhydrase 1(Car1) | 4.7 | 1.5 |

| Hemoglobin, beta adult minor chain (Hbb-b2) | 3.1 | 3.4 |

| CD28 antigen | 4.2 | 1.8 |

| Rab38, member of RAS oncogene family (Rab38) | 2.4 | 1.6 |

| Hemoglobin alpha, adult chain 1 (Hba-a1) | 1.7 | 1.9 |

| Myosin light chain 2, precursor lymphocyte-specific (Mylc2pl) | 4.7 | 1.9 |

| Pre B-cell leukemia transcription factor 3 (Pbx3) | 5.4 | 1.9 |

| Myocyte enhancer factor 2C (Mef2c) | 2.0 | 1.6 |

| Calcitonin receptor-like (Calcrl) | 5.6 | 1.7 |

| Transcription factor 12 (Tcf12) | 1.8 | 2.1 |

| Hemoglobin alpha, adult chain 1 (Hba-a1) | 1.7 | 2.0 |

| Prion protein (Prnp) | 3.2 | 3.1 |

| Homeo box A5 (Hoxa5) | 12.1 | 1.7 |

| RIKEN cDNA 4732435N03 gene | 2.3 | 1.5 |

| Hemoglobin alpha, adult chain 1 (Hba-a1) | 2.4 | 2.9 |

| Homeo box A9 (Hoxa9) | 11.3 | 2.4 |

| Cysteine-rich secretory protein 1 (Crisp1) | 126.5 | −1.6 |

| Kit oncogene (Kit) | −2.8 | −1.9 |

| Small muscle protein, X-linked (Smpx) | −2.4 | −2.2 |

| Aldo-keto reductase family 1, member C18 (Akr1c18) | −2.8 | 2.6 |

| Complement component 3a receptor 1 (C3ar1) | −1.9 | −2.2 |

| Cytokine-dependent hematopoietic cell linker (Clnk) | −2.5 | −1.7 |

| Heparan sulfate 6-O-sulfotransferase 2 (Hs6st2) | −2.3 | −1.9 |

| 3'-phosphoadenosine 5'-phosphosulfate synthase 2 (Papss2) | −2.5 | −1.6 |

| Mast cell protease 1 (Mcpt1) | −10.4 | −4.2 |

| Reprimo, TP53 dependent G2 arrest mediator candidate (Rprm) | −1.9 | −1.8 |

| Elastase 2, neutrophil (Ela2) | −2.4 | −1.6 |

| Mast cell protease 4 (Mcpt4) | −10.0 | −3.1 |

| Tryptase alpha/beta 1 (Tpsab1) | −15.4 | −2.2 |

| Heparan sulfate 6-O-sulfotransferase 2 (Hs6st2) | −4.8 | −3.0 |

| Kit oncogene (Kit) | −2.5 | −1.9 |

| Gene name . | Fold change* . | |

|---|---|---|

| NUP98/HOXA9 . | NUP98/HHEX . | |

| Prion protein (Prnp) | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| Carbonic anhydrase 1(Car1) | 4.7 | 1.5 |

| Hemoglobin, beta adult minor chain (Hbb-b2) | 3.1 | 3.4 |

| CD28 antigen | 4.2 | 1.8 |

| Rab38, member of RAS oncogene family (Rab38) | 2.4 | 1.6 |

| Hemoglobin alpha, adult chain 1 (Hba-a1) | 1.7 | 1.9 |

| Myosin light chain 2, precursor lymphocyte-specific (Mylc2pl) | 4.7 | 1.9 |

| Pre B-cell leukemia transcription factor 3 (Pbx3) | 5.4 | 1.9 |

| Myocyte enhancer factor 2C (Mef2c) | 2.0 | 1.6 |

| Calcitonin receptor-like (Calcrl) | 5.6 | 1.7 |

| Transcription factor 12 (Tcf12) | 1.8 | 2.1 |

| Hemoglobin alpha, adult chain 1 (Hba-a1) | 1.7 | 2.0 |

| Prion protein (Prnp) | 3.2 | 3.1 |

| Homeo box A5 (Hoxa5) | 12.1 | 1.7 |

| RIKEN cDNA 4732435N03 gene | 2.3 | 1.5 |

| Hemoglobin alpha, adult chain 1 (Hba-a1) | 2.4 | 2.9 |

| Homeo box A9 (Hoxa9) | 11.3 | 2.4 |

| Cysteine-rich secretory protein 1 (Crisp1) | 126.5 | −1.6 |

| Kit oncogene (Kit) | −2.8 | −1.9 |

| Small muscle protein, X-linked (Smpx) | −2.4 | −2.2 |

| Aldo-keto reductase family 1, member C18 (Akr1c18) | −2.8 | 2.6 |

| Complement component 3a receptor 1 (C3ar1) | −1.9 | −2.2 |

| Cytokine-dependent hematopoietic cell linker (Clnk) | −2.5 | −1.7 |

| Heparan sulfate 6-O-sulfotransferase 2 (Hs6st2) | −2.3 | −1.9 |

| 3'-phosphoadenosine 5'-phosphosulfate synthase 2 (Papss2) | −2.5 | −1.6 |

| Mast cell protease 1 (Mcpt1) | −10.4 | −4.2 |

| Reprimo, TP53 dependent G2 arrest mediator candidate (Rprm) | −1.9 | −1.8 |

| Elastase 2, neutrophil (Ela2) | −2.4 | −1.6 |

| Mast cell protease 4 (Mcpt4) | −10.0 | −3.1 |

| Tryptase alpha/beta 1 (Tpsab1) | −15.4 | −2.2 |

| Heparan sulfate 6-O-sulfotransferase 2 (Hs6st2) | −4.8 | −3.0 |

| Kit oncogene (Kit) | −2.5 | −1.9 |

Discussion

Here we have identified HHEX as a new member of a group of homeodomain proteins including homeotic genes (HOXA9, HOXA11, HOXA13, HOXC11, HOXC13, HOXD11, HOXD13) and class-2 homeobox genes (PMX1, PMX2) that are fused to NUP98 in hematologic malignancies.3-5 HHEX, also known as PRH (proline-rich homeobox), was initially cloned from an AML cell line and shown as predominantly expressed in hematopoietic tissue and the liver.35,36 Expression of HHEX is down-regulated during terminal differentiation of hematopoietic cells.16,35,37 HHEX acts primarily as a transcriptional repressor: C-terminal HHEX homeodomain binds to TATA box sequences, and a proline-rich N-terminal domain interacts with members of the Groucho/TLE (transducin-like enhancer of split) family of corepressor proteins.33,34 In the resulting NUP98/HHEX, the proline-rich domain is replaced by the GLFG repeats of NUP98 with the consequence that the fusion acts as a transcriptional activator on HHEX/PRH responsive elements (Figure 5). The retention of the HHEX homeodomain in the fusion suggests that NUP98/HHEX may deregulate HHEX target genes in hematopoietic progenitor cells. This hypothesis is currently being explored by gene expression profiling experiments. There is increasing evidence that HHEX plays a more general role in cancer pathogenesis. Activation of HHEX by retroviral insertion in tumors of AKXD recombinant inbred mice suggested that deregulated expression of HHEX might contribute to B-cell leukemia.38 Overexpression of HHEX in hematopoietic precursor cells led to the development of T-cell derived lymphomas in approximately 60% of mice that underwent transplantation.39 Here, we demonstrated that a NUP98/HHEX fusion resulting from t(10;11)(q23;p15) has transforming activity in vitro and in vivo. One-hundred percent of mice with NUP98/HHEX that underwent transplantation developed an acute leukemia involving the myeloid as well as the B-cell lineage (based on immunophenotype and IgH gene rearrangements), a phenotype that has previously not been observed by expression of other NUP98 fusion genes. This phenotype closely resembles leukemia induced in mice by expression of fusions such as MLL/ENL, CALM/AF10, or NUP98/HOXD13 and presumably reflects transformation of these fusions of a biphenotypic lymphoid/myeloid progenitor cell.28,40-43

Comparative analysis of NUP98/HHEX revealed a high degree of similarity with NUP98/HOXA9 regarding transforming activity and induction of putative downstream target genes. Both fusions mediate aberrant self-renewal capacity to murine hematopoietic progenitor cells (as assessed in serial replating assays) and allow the generation of IL-3–dependent cell lines stably expressing the fusion7,8,10,11 (Figures 2,4). In addition, transplantation of bone marrow expressing these fusions leads to induction of an acute leukemic phenotype after long latency6,10 (Figure 6). However the potency of the homeodomain fused to NUP98 clearly dictates the transforming potential. Fusions of NUP98 to HOXA9, HOXA10, HOXB3, or HOXD13 have transforming activity in vitro and induce acute leukemia in a murine bone marrow transplant model (or in transgenic animals) with different penetrance and latency.6,10-12

Our results suggest the existence of (partially) overlapping molecular transformation mechanisms. Indeed, comparative gene expression profiling shows activation of a partly overlapping set of target genes for NUP98/HHEX and NUP98/HOXA9. For example, Hoxa5, Hoxa9, Flt3, and Pbx3 have been described as being deregulated by different NUP98/HD fusions in the mouse as well as in the human system44-47 (Figure 7). Interestingly, leukemic blasts from secondary transplants are characterized by an important up-regulation of Flt3 expression (Figure 7E). These observations suggest direct functional cooperation of Flt3 with NUP98/HHEX as recently demonstrated for NUP98/HOXA10.48

The structure-function analysis of the transforming potential of NUP98/HHEX (Figures 2,Figure 3–4; S2) suggests that integrity of the GLFG repeats is essential for providing serial replating capacity to bone marrow progenitor cells. Whether this part of the fusion might serve as an oligomerization and/or protein/protein interface is the subject of ongoing investigations. Nevertheless, these results suggest possible therapeutic interference by targeting NUP98 GFLG repeat domains (eg, with small molecules), or by inactivating DNA binding of the specific homeodomain fusion protein. An alternative strategy to impair transformation is to block the activation of expression or activity of common downstream target genes. For example, NUP98/HHEX- and NUP98/HOXA9-expressing murine leukemic blasts as well as AML cells from patients carrying these fusions are characterized by strong up-regulation of FLT3 expression. This suggests that these cells will be sensitive to small molecule FLT3-kinase inhibitors (Figure 7). However, several clinical trials have reported only transient hematologic responses to single-drug FLT3 inhibitor regimens in acute leukemia patients. Therefore, therapeutic targeting of other common targets will be necessary.49 It is therefore interesting to note that in addition to Flt3, Hoxa5, Hoxa9, Pbx3, and Mef2c have been identified not only to be regulated by NUP98-HD fusions, but also as putative downstream effectors of malignant transformation by other leukemogenic class II fusions (such as MLL fusions including MLL/ENL, MLL/AF4, MLL/AF9, or MLL/CBP) and merit further characterization as potential therapeutic targets.50-54 Taken together, our results suggest that cooperation of class II mutations (such as NUP98/HD or MLL/X fusions) leading to reactivation of HOX genes with deregulated FLT3 signaling (either by mutations or deregulated expression) is a major mechanism underlying human acute myeloid leukemia.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Copeland (Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology, Singapore) for technical help and for retroviral insertion cloning. We appreciate technical support and help from V. Jaeggin, U. Schneider, V. Pogacic, and R. Tiedt. We also thank R. Skoda for reading the paper.

This work was supported by the Gertrude von Meissner Foundation (Basel, Switzerland) and the Swiss National Science Foundation (Berne, Switzerland; 3100A0-116587/1). J.S. holds a research professorship from the Gertrude von Meissner Foundation. C.M. is supported by Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC), Milano, Italy.

Authorship

Contribution: D.J., P.G., T.L., S.E., R.L.S., C.D., and F.B. performed and analyzed research; P.-S.J. and C.M. designed and analyzed research; M.B. and A.S. provided critical materials; J.S. designed, performed, and analyzed research and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Juerg Schwaller, University Hospital Basel, Department of Biomedicine, Hebelstrasse 20, CH-4031 Basel, Switzerland; e-mail: j.schwaller@unibas.ch.

References

Author notes

*D.J. and P.G. contributed equally to this work.

†C.M. and J.S. contributed equally to this work.

![Figure 1. t(10;11)(q23;p15) results in a NUP98/HHEX fusion gene. (A) The G-banded karyotype is 45, X,−Y, t(10;11)(q23;p15)[15]/46, XY[5]. The arrows indicate the reciprocal chromosome translocations. (B) RACE-PCR and genomic characterization: NUP98 and HHEX are fused in-frame, joining nucleotide 1718 (exon 13) of NUP98 to nucleotide 426 (exon 2) of HHEX. Genomic breakpoint occurs inside the intron 13 in NUP98 gene and inside the exon 2 in HHEX gene joining intron 13 of NUP98 to exon 2 of HHEX (nucleotide 418). (C) Double-color double-fusion FISH assay. RP5-1173K1 (red) and RP11-469M1 (green) give a red signal on normal 11, a green signal on normal 10, and a red/green signal on both der(11) and der(10) (arrows).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/111/12/10.1182_blood-2007-09-108175/6/m_zh80120820370001.jpeg?Expires=1764958057&Signature=r0X0KpLbwEAoqccfgB-oqnlvQVmVRtDUUQQdIB~ZoqgAH2VyCTP48liHI~J1Yd4JTuu4OF4FA7ZClCIi6Zq0vThDlIQpvxrX0umFUMn4vhpV8dZJbYKNN74aagZ~Y8AglorU985BsCocQ60-TJMW2T3Tn6TCLXzv7SEHxCsUjRTWwSRsU7Ndqu04hlzI~YuagGkdHl-itauZTzsa0JecOurrmwas1VvbF0k2oPNIAMcUYBeKaYqecGASX0huwA3Dt5fupBuxPr9u2APaasMqV7fdOmy~SBr9WDhSd3GVKtHd31H3CkvkFSlw5lnKfxyup6jMtBpapZ7ZltSgDcpz2A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 6. Expression of NUP98/HHEX induces acute leukemia in mice. (A) Kaplan-Meier plot of primary recipients that received a transplant of NUP98/HHEX-transduced bone marrow cells (solid line, n = 10 average latency [285 ± 15 days]. Secondary recipients (dashed line, n = 10) succumbed to the disease with reduced latency (100 ± 20 days). Bone marrow transplantations have been done in 2 independent series. (B) Histology of representative primary mouse demonstrated the presence of leukemic blasts in blood smears and extensive leukemia tissue infiltration of organs including the spleen, liver, and lymph nodes. (C) Immunophenotyping of leukemic cells. Flow cytometric profiles of bone marrow–derived blasts of a representative NUP98/HHEX leukemia mouse. Infected cells are identified by EYFP+ fluorescence. (D) Expression of NUP98/HHEX fusion in spleen, bone marrow, and peripheral blood of 2 representative diseased mice was analyzed by RT-PCR analysis. (E) Viral integration analysis by Southern blotting of EcoRI-digested genomic DNA probed with an EYFP probe shows the clonal character of the disease. (F) Retroviral insertion sites in leukemic blasts from 4 mice with NUP98/HHEX-induced disease that underwent transplantation. Insertions were cloned using a splinkerette-PCR approach.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/111/12/10.1182_blood-2007-09-108175/6/m_zh80120820370006.jpeg?Expires=1764958057&Signature=J-sT74238BDQuwzKUX0PW2prO~XMQbcvss~0FtWAWKGmSxV-vfPWFWUyCvCdx929QlbGQVloVw6wiYDzVKAfgcBiI6jS7MLmgfzT2zHm3RD4riIMVBVgFfoj4XXoTxXpR6PYkakSctkYYSf00DiyxJ0iPUG9pb7nNDeOAv5WJE0hkjP4gwEJnbhUZ4-~TH4uXlDxyS36DM83JLTPeg~dhhW0z~xFx-XgNmSfxdkrwBqz96jAfRl1ArG0qyUifCBzTfY9kkrtj9uyZSbtesB1NGEj8pzs4qo6oRAylNtQhRTDER8tsiv1y4IJsVXKo9kulfOrbeIuHEnr0Hj7gRTypQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)