Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are a self-renewing population of bone marrow cells that replenish the cellular elements of blood throughout life. HSCs represent a paradigm for the study of stem-cell biology, because robust methods for prospective isolation of HSCs have facilitated rigorous characterization of these cells. Recently, a new isolation method was reported, using the SLAM family of cell-surface markers, including CD150 (SlamF1), to offer potential advantages over established protocols. We examined the overlap between SLAM family member expression with an established isolation scheme based on Hoechst dye efflux (side population; SP) in conjunction with canonical HSC cell-surface markers (Sca-1, c-Kit, and lineage markers). Importantly, we find that stringent gating of SLAM markers is essential to achieving purity in HSC isolation and that the inclusion of canonical HSC markers in the SLAM scheme can greatly augment HSC purity. Furthermore, we observe that both CD150+ and CD150− cells can be found within the SP population and that both populations can contribute to long-term multilineage reconstitution. Thus, using SLAM family markers to isolate HSCs excludes a substantial fraction of the marrow HSC compartment. Interestingly, these 2 subpopulations are functionally distinct, with respect to lineage output as well as proliferative status.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are a self-renewing population of bone marrow cells with the developmental potential to give rise to all of the differentiated cellular components of blood. HSCs possess enormous therapeutic potential in the context of transplantation and regenerative medicine, and this fact, combined with well-defined methods for the prospective isolation of HSCs as well as robust functional assays for HSC function, has established the HSC as a powerful paradigm for studying basic stem-cell biology. Despite the existence of several strategies for the purification of the most primitive long-term HSC (LT-HSC) populations from fractionated murine and human marrow,1,,–4 these current methods are not without drawbacks, thus prompting continued interest in identifying refined methods of HSC isolation.

LT-HSCs are isolated by flow cytometry using cell-surface markers alone or in combination with dye efflux properties unique to HSCs. Although several variations on these themes exist, the most commonly used strategies in each category are the c-Kit+, Thy1.1−/lo, Sca-1+, lineage marker negative (lin−/lo; KTSL) cell-surface scheme,5 and Hoechst dye exclusion (side population; SP).1 Use of these strategies has allowed the prospective isolation of LT-HSCs to high purity, yet these protocols still have disadvantages. The KTSL scheme is limited to strains expressing the Thy1.1 allele and requires too many antibodies to be practical for histologic techniques (eg, the localization of HSCs in their bone marrow niche). Likewise, selection of cells with low amounts of Hoechst dye in the SP strategy is also incompatible with in situ histologic analysis of HSCs and requires some expertise to achieve reproducible purifications.

It has been proposed that the SLAM family of cell-surface markers might be used as part of an HSC isolation scheme instead of previously established methods.6 These studies suggest that multiple SLAM markers, a family of cell-surface proteins originally characterized in lymphocyte signaling,7 can be used in combination to fractionate the HSC potential of adult murine bone marrow. LT-HSCs were reported as positive for CD150 (Slamf1) and negative for CD48, CD244, and CD41. When using these markers together with other known HSC markers, the researchers reported that bone marrow population of CD150+, CD48−, Sca-1+, c-Kit+ cells contained LT-HSC activity. Indeed, this population was reported to yield a single-cell reconstitution frequency of 48%, higher than previously reported for KTSL or SP–Kit+Lineage−/loSca-1+ cells (5%-35%).6,11 Importantly, the researchers also reported that the CD150− and CD48+ fractions of marrow did not contain appreciable long-term, multilineage-reconstituting ability in murine bone marrow transplantation assays.

This SLAM-based scheme of HSC isolation would have its advantages; it requires fewer antibodies (and, thus, expense) than the KTSL scheme and is reported to be useful across all mouse strains thus far tested.6 Further, compared with SP analysis, SLAM staining could require less technical expertise and would be more compatible with certain HSC assays requiring fixation. However, because SLAM-purified HSCs are beginning to enter into common use, we felt it prudent to examine the degree of overlap between SLAM and other established isolation methods, to ensure that conclusions drawn by groups using different techniques are truly generalizable.

Here, we report the results of experiments assessing the relation of SLAM-defined and SP-defined HSCs, because the latter method is one with which we have considerable experience. More specifically, we have investigated the extent to which CD150 serves as a positive HSC marker within the SP and have shown that LT-HSCs exhibit a bimodal distribution of CD150 expression, which reflects underlying functional heterogeneity in the LT-HSC compartment and that both CD150− and CD150+ SP cells are functional LT-HSCs.

Methods

Mice and HSC purification

All mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free barrier facility and fed autoclaved acidified water and mouse chow ad libitum. Whole bone marrow was isolated, and SP cell staining was performed with the vital dye Hoechst 33342 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) as previously reported.1 If SP cells were enriched for Sca-1 expression, then cells were resuspended at 108 cells/mL, stained on ice with anti–mouse Sca-1–biotin (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) for 15 minutes, resuspended at 1.25 × 108 cells/mL, incubated with 200 μL/mL of magnetic antibiotin microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA) for 10 minutes at 4°C, rinsed with staining buffer, resuspended at 2 × 108 cells/mL, and magnetically enriched on an AutoMACS instrument (Miltenyi). For antibody staining, cells were suspended at a concentration of 108 cells/mL and incubated on ice for 15 minutes with strepavidin-Alexa488 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA); c-Kit–APC (eBioscience); PE-Cy5–conjugated Mac-1, Gr-1, CD4, CD8, B220, and Ter119 (eBioscience); and CD150-PE (BioLegend, San Diego, CA; TC15-12F12.2 clone). A FITC-conjugated hamster IgG (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA) isotype control was used for CD48 and CD41, and a PE-conjugated rat IgG2 isotype control (BD PharMingen) was used for CD150. Cell sorting and analysis were performed on a MoFlo cell sorter (Dako North America, Carpinteria, CA), and additional analysis was accomplished with an LSRII (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Transplantation and peripheral blood analysis

After a split dose of 10.5 Gy of whole-body irradiation, C57Bl/6-CD45.1 recipients were transplanted by retroorbital intravenous injection with 100 C57Bl/6 SPKLS cells that were either CD150+, CD150−, or ungated with respect to CD150. Donor CD45.2 cells were competed against 2.5 × 105 CD45.1 whole bone marrow (WBM) cells. For peripheral blood analysis, mice were bled at 4, 8, 12, 16, and 24 weeks after transplantation; the red blood cells were lysed, and each sample was incubated with CD45.1-APC, CD45.2-FITC, CD4-pacific blue, CD8-pacific blue, B220-pacific blue, B220-PE-cy7, Mac1-PE-cy7, and Gr-1-PE-cy7 antibodies. Samples were analyzed on a LSRII (Becton Dickinson) instrument.

Progenitor and hematopoietic chimerism analysis

Twenty-four weeks after transplantation, recipients were killed, and bone marrow, tissue, and thymus were isolated from all recipients. All tissues were analyzed with antibodies to CD45.1 and CD45.2. Bone marrow samples were further analyzed using antibody schemes to identify the CD45.2-derived KLS (c-Kit+, lin−/lo, and Sca-1+), MP (myeloid progenitor), and CLP (common lymphoid progenitor) compartments as previously described.8,9 For KLS and CLP analysis, marrow was stained with a Lin cocktail conjugated to pacific blue (B220, CD3, CD4, CD8, Gr-1, Mac1, Ter119), Sca-1–FITC, c-Kit–PE, and Il7ra–PE-Cy7 (eBioscience). For MP analysis bone marrow was stained with a cocktail consisting of a Lin cocktail conjugated to pacific blue (B220, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19, Gr-1, Ter119), Sca-1–FITC, c-Kit–PE, and Il7Ra–PE-Cy7 (eBioscience), and MPs were defined as lineage and IL7Rα negative, c-Kit positive, and Sca-1 negative. For SP analysis, bone marrow samples from each recipient were Hoechst stained, as above, and enriched with anti–c-Kit microbeads (Miltenyi), then analyzed.

BrdU labeling and analysis

Mice received an initial intraperitoneal injection of BrdU (Sigma-Aldrich; 1 mg/6 g mouse weight), followed by inclusion of BrdU in the drinking water at 1 mg/mL for 3 subsequent days. Mice were then killed, and Sca-1+lin− SP cells were sorted on the basis of CD150 and Hoechst efflux into a carrier population of 500 000 B220+ splenocytes, as previously described.10 Samples were prepared for analysis of BrdU incorporation using the FITC BrdU Flow c-Kit (BD PharMingen), and samples were reanalyzed by flow cytometry. On reanalysis, HSCs were readily distinguishable from carrier cells as Sca-1+ and B220− and were gated for analysis of BrdU incorporation.

Statistics

Student t test was used for statistical analyses, when appropriate. Significance is indicated on the figures using the following convention: *P less than .05, **P less than .01, ***P less than .001, n.s. indicates not significant. Error bars in all panels represent the SEM.

Results

SLAM-defined HSCs incompletely overlap with SP-defined HSCs

To determine the degree of correspondence between HSCs purified by SLAM markers versus HSCs identified by SP, we performed these 2 staining schemes simultaneously, which enabled us to examine whether all cells identified by SLAM markers exhibited the SP phenotype and whether all SP-defined HSCs exhibited the reported SLAM marker profile. Using mouse C57Bl/6 bone marrow, we first used only CD150, CD48, and CD41 as marker criteria and examined where the CD150+CD48−CD41− population (hereafter called SLAM cells) fell within the SP plot (Hoechst Red vs Hoechst Blue). We observed, by using gates defined strictly with isotype controls (Figure 1A), that only approximately 20% of SLAM cells were found to reside within the SP (Figure 1B). Further, parallel analysis of this isotype-defined SLAM population showed that only approximately 23% of SLAM cells expressed the canonical stem-cell markers c-Kit and Sca-1. Because we have previously shown that the SP contains all HSC activity within the bone marrow,1,11 we tested HSC function in both the SLAM-SP and SLAM–non-SP fractions to determine whether SLAM–non-SP might represent a previously overlooked stem cell compartment. Consistent with our previous results, we found that only the SP cells within the SLAM fraction contained long-term reconstituting ability (Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article), showing that non-SP SLAM cells are not HSCs and that HSC activity correlates faithfully with the SP phenotype, even after enrichment of WBM using SLAM markers.

High correspondence of SLAM cells with the side population is dependent on stringent CD150 gating. (A) Whole bone marrow isotype controls for SLAM family members (CD48, CD41, and CD150). (B) When using SLAM family members to define HSCs, based on isotype controls, 45% of WBM cells are CD150+ and 0.4% are CD150+CD48−CD41− (termed SLAM cells). Only 23% of these cells are c-Kit and Sca-1 positive, and only 20% are side population (SP) cells. (C) When the gating for CD150 is more stringent (asterisks), reducing the number of SLAM cells to 0.01%, then both the percentage of c-Kit+ Sca-1+ and SP cells within the SLAM population increases to 86% and 84%, respectively. Percentages shown correspond to the gated proportion of the plot.

High correspondence of SLAM cells with the side population is dependent on stringent CD150 gating. (A) Whole bone marrow isotype controls for SLAM family members (CD48, CD41, and CD150). (B) When using SLAM family members to define HSCs, based on isotype controls, 45% of WBM cells are CD150+ and 0.4% are CD150+CD48−CD41− (termed SLAM cells). Only 23% of these cells are c-Kit and Sca-1 positive, and only 20% are side population (SP) cells. (C) When the gating for CD150 is more stringent (asterisks), reducing the number of SLAM cells to 0.01%, then both the percentage of c-Kit+ Sca-1+ and SP cells within the SLAM population increases to 86% and 84%, respectively. Percentages shown correspond to the gated proportion of the plot.

Given the presence of non-HSCs in the SLAM population, in contrast to the previous report,6 we sought to test additional strategies to improve the correspondence between SLAM-defined and SP-defined HSCs. First, the addition of Sca-1+ c-Kit+ marker criteria to SLAM cells dramatically improved the results, such that approximately 85% of events were now SP cells (Figure S2). We further observed that by using stringent gating for CD150, selecting cells in the top 1% of CD150 staining (CD150high), the overlap once again improved substantially, with approximately 85% of CD150high SLAM population exhibiting the SP Sca-1+ c-Kit+ phenotype (Figure 1C). These results would suggest that to achieve high HSC purity, users of the SLAM-sorting protocol should not rely only on CD150 and CD48 expression alone; rather, stringent SLAM gates should be coupled with other defined HSC markers (such as Sca-1, c-Kit, or SP). In addition, the need to select the brightest 1% of CD150high cells to achieve reasonable overlap between SLAM and SP cells suggests that use of CD150 as a marker of HSCs for in situ sections could be challenging indeed.

CD150 divides the SP into 2 distinct fractions. (A) From mice at 10 weeks of age, bone marrow SP cells that are c-Kit+, Sca-1+, Lin− (SPKLS) were examined for expression of SLAM family members CD41, CD48, and CD150. (B) At 10 weeks of age, all SPKLS cells express little or no CD41 and CD48, and only one-third of SPKLS cells express CD150. Percentages shown correspond to the gated proportion of the plot.

CD150 divides the SP into 2 distinct fractions. (A) From mice at 10 weeks of age, bone marrow SP cells that are c-Kit+, Sca-1+, Lin− (SPKLS) were examined for expression of SLAM family members CD41, CD48, and CD150. (B) At 10 weeks of age, all SPKLS cells express little or no CD41 and CD48, and only one-third of SPKLS cells express CD150. Percentages shown correspond to the gated proportion of the plot.

SP-KLS cells are heterogeneous for CD150 cell-surface expression

We next sought to examine whether HSCs defined by SP are universally positive for CD150 and negative for CD48 and CD41. To ensure that we obtain the most highly purified population, we typically select SP cells that are also c-Kit+, lin−/lo, and Sca-1+, which excludes the approximate 15% of SP cells that are not HSCs (these cells will hereafter be called SPKLS). Isolated murine bone marrow was stained with Hoechst, antibodies to Sca-1, c-Kit, CD150, as well as the cocktail of antibodies to differentiation markers (Lin). Using stringent SPKLS gating (Figure 2A), we were surprised to observe that the SPKLS population is not in fact homogenous with respect to CD150 staining (Figure 2B) and that 2 clear populations of CD150+ SPKLS cells and CD150− SPKLS cells can be delineated. Notably, this is the first such marker we have observed to exhibit significant heterogeneity within SPKLS. Finally, in parallel experiments replacing anti-CD150 with anti-CD41 or anti-CD48 in our staining scheme, we were able to confirm that, at baseline, SPKLS cells do not express cell-surface CD41 or CD48 (97% negative; 83% negative, > 95% negative/low; Figure 2B), leading us to conclude that differences between SLAM and SP HSC populations are derived from heterogeneous CD150 expression, as opposed to CD48 or CD41.

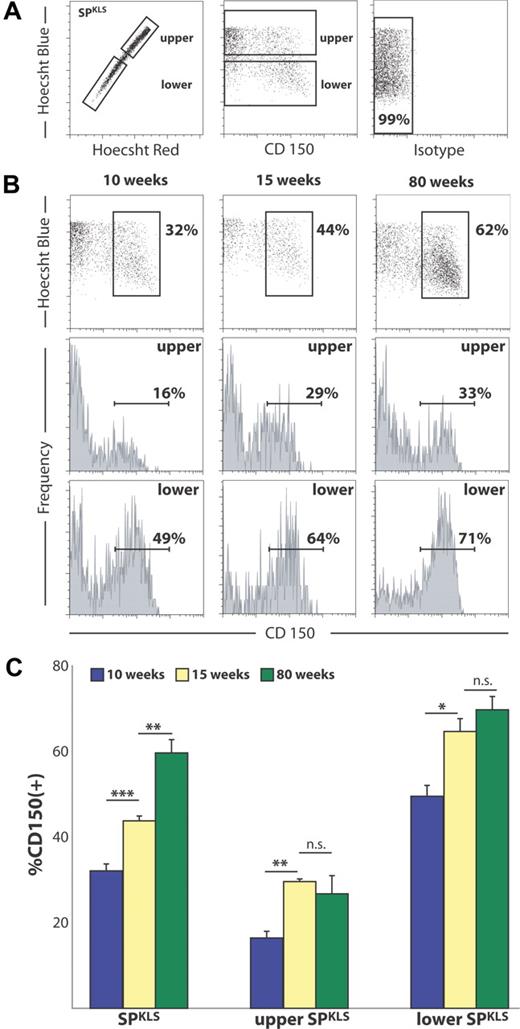

To further refine our analysis of CD150 variability within the SPKLS population, we next examined CD150 expression with respect to Hoechst efflux capacity (Figure 3A). As has been previously described, the efficiency of Hoechst dye efflux correlates with the degree of long-term HSC potential; thus, the SP represents a gradient of HSC potency, with the most primitive LT-HSCs residing in the lower SP and more short-term potential in the upper SP.2 With respect to CD150 status as a function of position within the SP, we observed that the lower SP has a significantly higher percentage of CD150+ cells than does the upper SP. For example, at 10 weeks of age, the lower SP is approximately 49% CD150+ (49.55% ± 4.38%), whereas the upper SP is approximately 16% CD150+ (16.43% ± 2.72%; Figure 3B). It is important to note that, although the frequency of CD150 positivity correlates with increasing HSC dye efflux capacity, CD150− cells are present even in the most distal regions of the lower SP (Figure 3B), where the most primitive HSCs are found.2

CD150 is heterogeneous with respect to dye efflux and changes with age within the SP. (A) The analysis scheme divides the SP into upper and lower portions, both of which are heterogeneous with respect to CD150. These relations are quantified in subsequent panels. Percentages shown correspond to the gated proportion of the plot. (B) The proportion of CD150+ cells increases with age within the SP. (C) When the shift in CD150+ SP cells is quantified, there is a significant change with age, which varies between upper and lower SP. Error bars represent SEM.

CD150 is heterogeneous with respect to dye efflux and changes with age within the SP. (A) The analysis scheme divides the SP into upper and lower portions, both of which are heterogeneous with respect to CD150. These relations are quantified in subsequent panels. Percentages shown correspond to the gated proportion of the plot. (B) The proportion of CD150+ cells increases with age within the SP. (C) When the shift in CD150+ SP cells is quantified, there is a significant change with age, which varies between upper and lower SP. Error bars represent SEM.

Next, we sought to examine the SPKLS population for any changes in CD150 status over the course of adult development and aging. To accomplish these analyses, marrow was isolated from C57Bl/6 mice over a range of ages (10, 15, and 80 weeks of age), and CD150 expression within the SPKLS population was determined, while also paying particular attention to how CD150 was distributed in both the lower and upper fractions of the SP (gating shown in Figure 3A). We observed that cell-surface expression of CD150 is not static with respect to age, but it indeed undergoes dramatic increases in the SP HSC population between 10 and 15 weeks of adult development (Figure 3C). Furthermore, this trend of increasing CD150 expression continues with age up to 80 weeks, such that the SPKLS compartment of aged animals is predominantly CD150+ (> 62%). Given the approximately 3-fold increase in marrow cellularity and a 6- to 10-fold increase in SPKLS cells with respect to age in these animals,12 it seems likely that this shift in expression reflects an absolute expansion of the CD150+ SPKLS cells, rather than a loss of the CD150− SPKLS population. The biologic significance of this shift remains unclear, but it suggests that CD150 might play a role in the alteration of HSC function with age. Mindful of these age-related changes, we took care to use animals of a consistent age (10 weeks) in all additional experiments.

Finally, we note that, although the overall fraction of CD150+ cells within the SP increases substantially from young to old mice (15-80 weeks), the increase is proportional with respect to the upper and lower SP; ie, the upper SP remains approximately 25% CD150+, and the lower SP is still approximately 65% CD150+ (Figure 3C). Thus, the change in overall CD150 expression with age is not likely attributable to an asymmetric expansion of lower SP.

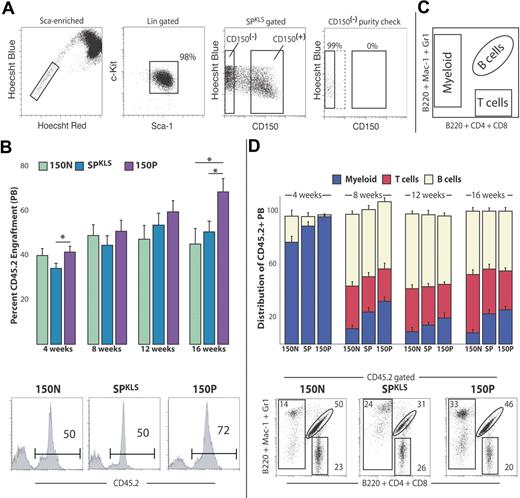

Both CD150+ and CD150− SPKLS cells are LT-HSCs

Previous studies reported that the CD150+ fraction of whole bone marrow was the exclusive reservoir of LT-HSC activity, with no reconstitution ability observed in CD150− marrow.6 Therefore, we sought to compare HSC activity (as defined as the ability to support long-term multilineage hematopoiesis in transplant recipients) for the CD150+ and CD150− fractions of SPKLS cells. We performed purified HSC transplantation experiments using exceptionally stringent gates (Figure 4a) to define CD150− and CD150+ populations so as to minimize potential cross contamination. SPKLS cells were sorted on the basis of CD150, as well as independently of CD150 status. Reflow analysis of sorted cells to check purity verified that cells sorted as CD150− SPKLS cells indeed contained no CD150+ cells. One hundred cells of each phenotype (SPKLS alone, CD150− SPKLS, and CD150+ SPKLS) were isolated from CD45.2 C57Bl/6 donors and transplanted into lethally irradiated congenic CD45.1 recipients, along with 250 000 WBM competitor cells from CD45.1 animals. Peripheral blood analysis was performed at successive 4-week intervals after transplantation. We found that all 3 sorted populations contributed robustly to the peripheral blood and were able to sustain multilineage engraftment of recipients beyond 16 weeks after transplantation, the time when only LT-HSCs contribute to blood, and progenitors have exhausted their limited self-renewal capacity (Figure 4B-D). Secondary transplantation experiments revealed that all 3 populations were capable of engrafting secondary hosts (Figure S3). Thus, this analysis unequivocally revealed that the CD150− SPKLS fraction possesses true LT-HSC activity.

CD150− side population cells possess long-term, multilineage reconstitution potential. (A) Representative sort scheme for transplants that are CD150+ (n = 10), CD150− (n = 14), or both (total SPKLS; n = 9) is shown. Sca-1/c-Kit and Hoechst Blue/CD150 scatter plots contain more cells to emphasize the CD150+ and CD150− populations. Exceptionally stringent gates were used to define CD150+ and CD150− subpopulations, and a purity check of sorted cells (using an example from a CD150− sort) was used to verify sort quality. The SPKLS donor population includes all events shown in the Hoechst Blue/CD150 scatter plot. (B) One hundred cells from each donor population were isolated from CD45.2 mice and transplanted into CD45.1 lethally irradiated recipient mice, along with 250 000 WBM competitor cells from CD45.1 animals. Donor-derived engraftment (percentage of CD45.2) within the peripheral blood was measured by flow cytometry at 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks after transplantation, indicating long-term engraftment (greater than 16 weeks) from all 3 populations. An example flow cytometric analysis of an individual animal from each cohort is shown. (C) Lineage contribution of donor-derived hematopoiesis was determined using a staining scheme (illustrated here) that separates the peripheral blood into myeloid cells, B cells, and T cells. (D) Donor- derived (percentage of CD45.2) multilineage reconstitution within the peripheral blood was measured by flow cytometry at 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks after transplantation, indicating long-term multilineage engraftment (16 weeks) from all 3 donor populations. The proportion of the specified lineages within all donor-derived test cells is indicated. An example flow cytometric analysis of an individual animal from each cohort is shown. Data shown are from 2 separate transplantations and are representative of several experiments. Donor-derived T cells were not observed at 4 weeks after transplantation. Error bars represent SEM. Percentages shown correspond to the gated proportion of the plot.

CD150− side population cells possess long-term, multilineage reconstitution potential. (A) Representative sort scheme for transplants that are CD150+ (n = 10), CD150− (n = 14), or both (total SPKLS; n = 9) is shown. Sca-1/c-Kit and Hoechst Blue/CD150 scatter plots contain more cells to emphasize the CD150+ and CD150− populations. Exceptionally stringent gates were used to define CD150+ and CD150− subpopulations, and a purity check of sorted cells (using an example from a CD150− sort) was used to verify sort quality. The SPKLS donor population includes all events shown in the Hoechst Blue/CD150 scatter plot. (B) One hundred cells from each donor population were isolated from CD45.2 mice and transplanted into CD45.1 lethally irradiated recipient mice, along with 250 000 WBM competitor cells from CD45.1 animals. Donor-derived engraftment (percentage of CD45.2) within the peripheral blood was measured by flow cytometry at 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks after transplantation, indicating long-term engraftment (greater than 16 weeks) from all 3 populations. An example flow cytometric analysis of an individual animal from each cohort is shown. (C) Lineage contribution of donor-derived hematopoiesis was determined using a staining scheme (illustrated here) that separates the peripheral blood into myeloid cells, B cells, and T cells. (D) Donor- derived (percentage of CD45.2) multilineage reconstitution within the peripheral blood was measured by flow cytometry at 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks after transplantation, indicating long-term multilineage engraftment (16 weeks) from all 3 donor populations. The proportion of the specified lineages within all donor-derived test cells is indicated. An example flow cytometric analysis of an individual animal from each cohort is shown. Data shown are from 2 separate transplantations and are representative of several experiments. Donor-derived T cells were not observed at 4 weeks after transplantation. Error bars represent SEM. Percentages shown correspond to the gated proportion of the plot.

Although the SPKLS population contained LT-HSC activity in both CD150+ and CD150− subsets, we did observe some differences in HSC function among the different sorted populations. CD150− SPKLS cells exhibited a slight, but statistically significant, reduction in contribution to peripheral blood chimerism. Perhaps most notably, CD150− SPKLS-derived hematopoiesis showed a tendency to skew toward lymphoid production at the expense of myeloid cell production. Observation of lineage contribution at an early time after transplantation (4 weeks) showed that, although CD150+ SPKLS donor cells contributed almost exclusively to myelopoiesis, the CD150− SPKLS population gave rise to donor-derived B cells. This phenomenon of greater lymphopoietic contribution of CD150− SPKLS cells persisted to long-term time points, with CD150+ SPKLS exhibiting significantly increased relative contribution to myeloid cells at each analysis (Figure 4D).

We further examined the engraftment behavior of CD150− and CD150+ SPKLS by performing an extensive analysis of CD45 chimerism in multiple hematopoietic tissues and compartments. Twenty-four weeks after transplantation, we were able to detect donor-derived hematopoiesis in all recipient groups across all observed compartments, including whole tissues (peripheral blood, bone marrow, spleen, thymus; Figure 5A) and stem/progenitor populations (myeloid progenitors [MPs], common lymphoid progenitors [CLPs], Sca-1+ c-Kit+ Lin− stem and progenitors [KLS], and SPKLS; Figure 5B), showing that all 3 donor populations are capable of long-term reconstitution of all stem and progenitor populations. Once again, however, the 3 populations performed slightly differently. CD150− SPKLS contribution to the MP, CLP, and KLS compartments was evident but significantly lower than that derived from CD150+ SPKLS; however, no statistically significant difference in contribution to the SPKLS compartment was observed. Sorting of single donor-derived SPKLS from recipients of all 3 test populations into methylcellulose colony-forming assays confirmed that all 3 donor populations gave rise to HSCs with myeloid potential (data not shown). Despite normal levels of engraftment in the spleen and peripheral blood, CD150− SPKLS donor HSCs did not engraft the recipient bone marrow or thymus with efficiency equal to the CD150+ SPKLS and SPKLS populations. However, although the CD150− SPKLS donor cells exhibited slight reductions in contribution to the peripheral blood (as noted above; Figure 4A), that deficit is not commensurate with the more pronounced difference observed in their contribution to bone marrow engraftment. We saw no overt evidence of extramedullary hematopoiesis in recipients of CD150− SPKLS cells, suggesting that even though their apparent bone marrow contribution is lower, other properties, such as their proliferative or differentiation capacity compensate to ensure sufficient peripheral blood production.

CD150− and CD150+ HSCs exhibit differences in contribution to various hematopoietic compartments 24 weeks after transplantation. (A) A significant decrease in donor-derived whole bone marrow (WBM) and thymus engraftment, measured by flow cytometry, was observed for CD150− SPKLS HSCs compared with CD150+ or whole SPKLS HSCs. No statistical difference was observed for donor-derived peripheral blood and spleen chimerism. (B) All 3 populations of SPKLS cells self-renew to give rise to comparable levels of SPKLS, although CD150− SPKLS generate lower levels of KLS, MP, and CLP compartments as measured by flow cytometry. (C) WBM was examined for the presence of donor-derived CD150+ and CD150− SPKLS within transplant recipients that received CD150+ or CD150− SPKLS cells. Both donor populations were able to produce CD150+ and CD150− SPKLS cells, indicating no clear-cut hierarchy between the CD150+ and CD150− SPKLS cells. In addition, CD150+ SPKLS donor cells exhibited a trend toward generating a higher proportion of CD150+ cells in the recipient SP. This result, although not statistically significant, suggests a preference for the CD150+ SPKLS to preferentially produce CD150+ SPKLS on transplantation. Error bars represent SEM.

CD150− and CD150+ HSCs exhibit differences in contribution to various hematopoietic compartments 24 weeks after transplantation. (A) A significant decrease in donor-derived whole bone marrow (WBM) and thymus engraftment, measured by flow cytometry, was observed for CD150− SPKLS HSCs compared with CD150+ or whole SPKLS HSCs. No statistical difference was observed for donor-derived peripheral blood and spleen chimerism. (B) All 3 populations of SPKLS cells self-renew to give rise to comparable levels of SPKLS, although CD150− SPKLS generate lower levels of KLS, MP, and CLP compartments as measured by flow cytometry. (C) WBM was examined for the presence of donor-derived CD150+ and CD150− SPKLS within transplant recipients that received CD150+ or CD150− SPKLS cells. Both donor populations were able to produce CD150+ and CD150− SPKLS cells, indicating no clear-cut hierarchy between the CD150+ and CD150− SPKLS cells. In addition, CD150+ SPKLS donor cells exhibited a trend toward generating a higher proportion of CD150+ cells in the recipient SP. This result, although not statistically significant, suggests a preference for the CD150+ SPKLS to preferentially produce CD150+ SPKLS on transplantation. Error bars represent SEM.

To examine whether CD150 status correlated with any detectable restriction of potential on LT-HSCs, we further analyzed the donor-derived SPKLS population in all recipients for CD150 expression (analogous to the analyses in Figure 3A). These results revealed that all 3 donor populations were able to give rise to both CD150− SPKLS and CD150+ SPKLS. Although we did observe some tendency for the CD150+ donor cells to preferentially generate CD150+ SPKLS, these results were not statistically significant (Figure 5C).

CD150− HSCs are more proliferative in vivo

Having established that the CD150− fraction of the SP compartment does indeed possess LT-HSC activity (albeit with subtle differences in hematopoietic output), we tried to further elucidate whether this marker heterogeneity correlated with any underlying differences in biologic function. To determine possible differences in cell cycle between CD150+ and CD150− SPKLS cells, mice were treated with BrdU, a synthetic thymidine analog that facilitates identification of cells that have undergone DNA synthesis. SPKLS cells were sorted from both the upper and lower SP and on the basis of their CD150 expression, and BrdU incorporation was analyzed by flow cytometry. CD150− SPKLS cells were found to be substantially more proliferative in vivo than their CD150+ SPKLS counterparts (Figure 6), most notably in the lower SP (32% versus 13% positivity). This result is particularly interesting in the context of the observation (above) that, although CD150− SPKLS HSCs engraft the bone marrow at lower levels after transplantation, they contribute to the peripheral blood almost equally as well as CD150+ SPKLS HSCs, perhaps because of enhanced proliferation.

CD150 marks a population of more quiescent HSCs. SPKLS cells fractionated based on position within the SP (Hoechst Blue fluorescence) and CD150 expression (gates i-iv) were isolated from mice treated with the nucleotide analog BrdU for 3 days and examined by flow cytometry for BrdU incorporation, an indicator of transition through the cell cycle. CD150− SPKLS cells were substantially more proliferative in vivo than their CD150+ SPKLS counterparts, with the lower SP being generally less in cell cycle than the upper SP. Percentages shown correspond to the gated proportion of the plot.

CD150 marks a population of more quiescent HSCs. SPKLS cells fractionated based on position within the SP (Hoechst Blue fluorescence) and CD150 expression (gates i-iv) were isolated from mice treated with the nucleotide analog BrdU for 3 days and examined by flow cytometry for BrdU incorporation, an indicator of transition through the cell cycle. CD150− SPKLS cells were substantially more proliferative in vivo than their CD150+ SPKLS counterparts, with the lower SP being generally less in cell cycle than the upper SP. Percentages shown correspond to the gated proportion of the plot.

Discussion

We have examined the overlap between 2 strategies for the prospective identification of HSCs in the adult bone marrow. Importantly, we do find that substantial overlap between the SLAM population and the SPKLS population exists. However, without stringent gating or additional stem cell markers, the SLAM population contains a significant proportion of non-SP cells (as shown in Figure 1), which, consistent with our previous results, lack functionally defined HSC activity. Although using SLAM markers in conjunction with Sca-1 and c-Kit expression can achieve good overlap with the SP HSC population, our data reveal that even this optimized SLAM scheme neglects a substantial population of CD150− LT-HSCs. Contrary to previous reports that the CD150− fraction of the adult bone marrow does not contain appreciable LT-HSC activity, our transplantation studies have shown that SPKLS CD150− cells are indeed functional HSCs, capable of supporting long-term multilineage hematopoiesis in transplant recipients and engrafting multiple hematopoietic tissues and compartments. This report is our first observation of a marker that divides the highly purified SPKLS HSC purification scheme into discrete subfractions, a remarkable finding, given that the SP was found to be highly homogeneous for other markers (Sca-1+, c-Kit+, EPCR, CD34−/lo, Flk2−) in past studies.1,2,11,13

The newfound phenotypic heterogeneity within the SP also reveals intriguing functional differences between the 2 CD150 compartments. Most subtly, CD150− SP cells have slightly lower reconstitution potential (relative to CD150+ SP cells), when measured by peripheral blood chimerism. Examination of CD150− SPKLS engrafted bone marrow reveals a larger deficit, yet, in addition to peripheral blood, these cells do contribute to the KLS, CLP, and MP progenitor populations, as well as the HSC compartment when measured long term (> 24 weeks). These slight engraftment differences may be in part due to proliferative differences we observed between the 2 HSC populations. Our observation that CD150− SP cells are more proliferative than their CD150+ counterparts might explain some of these phenomena, because a higher rate of proliferation may drive comparable peripheral blood reconstitution yet result in lower engraftment efficiency, because lower HSC engraftment efficiency correlates with S/G2/M stages of cell cycle.14 The more proliferative CD150− HSCs are found in higher proportions within the upper SP than in the lower SP, reinforcing the idea that quiescence correlates with greater dye-efflux capacity. More importantly, our demonstration that CD150 serves as a marker of relative proliferative status within the HSC compartment reveals unexpected functional heterogeneity within HSCs and has broader implications for the life cycle of an HSC as it transits between proliferative and quiescent phases.

On a practical level, these results have several implications for investigators seeking to use one or both of these methods for the isolation of HSCs. Our data show that stringent gating on CD150 (0.01% of WBM), far more stringent than background antibody staining established using isotype controls, is important to isolate high-purity functionally defined HSCs based on the SLAM strategy. Without stringent gating, as few as approximately one-third of the isolated cells may be functional HSCs. Users of the SLAM-based marker scheme are thus well served to consider inclusion of additional stem-cell markers (eg, SP or Sca-1 and c-Kit) to insulate against inappropriately permissive gating of CD150. Indeed, more recent reports using the SLAM gating scheme have also included Sca-1 and c-Kit.15,16 A second practical consideration implied by our data is that, when staining bone marrow in histologic sections using the SLAM markers, it may be difficult to discriminate the true CD150high cells (0.01% of WBM; Figure 1B), delimiting the HSC compartment, from the other top approximately 0.40% of CD150+ cells, which will define 40-fold more cells that are not HSCs. It is possible that the inability to distinguish CD150high cells from other CD150+ cells, particularly in histologic sections, has led to the controversy over what proportion of HSCs can be found in the endothelial cell niche,6 versus an osteoblast niche.17,18

Should further studies ultimately strengthen the hypothesis that an endothelial niche does exist for HSCs, our results may inform the resolution of this model with other published data. It has been previously established that specialized osteoblasts (spindle-shaped, N-cadherin osteoblasts, or SNO cells) provide a niche for HSCs along the endosteal lining of the marrow cavity.17,18 CD150 is known in T and B cells to coordinate immune cell activation and proliferation with the extracellular microenvironment.7 Taken together with evidence for multiple HSC niches within the marrow space, one interpretation of the existence of HSC populations heterogeneous with respect to CD150 might be that these 2 populations occupy different niches, with adhesion or engraftment within these specialized niches mediated by CD150 (a hypothetical function consistent with previous knowledge about how CD150 may act). Differences in the respective microenvironments might further regulate hematopoietic output, accounting for the observed preferential lymphoid production by CD150− SPKLS HSCs. Examining the bone marrow for localized expression of CD150 ligands may provide further evidence for the role of CD150 in niche specification.

The ability to delineate functionally distinct subsets of bona fide HSCs on the basis of CD150 expression shows that not all HSCs are absolutely equivalent in developmental capacity. These differences could be influenced by the niche from which the HSCs are derived, or other molecular factors inherent to the cells, such as differences in the concentration of particular transcription factors.19 Although surprising, these conclusions are supported by other observations derived from transplantation of single HSCs, which have shown that individual HSCs could give rise to lymphoid-biased, myeloid-biased, or balanced hematopoiesis,20,21 leading to a clonal diversity model of HSC potential. CD150 may distinguish these HSC subtypes. When transplanted, CD150− SPKLS cells resemble the reported lymphoid-biased HSCs in phenotype because they produce more B cells at early time points and reduced amounts of myeloid cells at late time points, compared with HSCs defined by whole SPKLS or CD150+ SPKLS.

One corollary of the clonal diversity model is that a change in HSC function observed at a population level could be explained through changes in the proportions of HSC subsets within the population. In this regard, it is worth noting the marked increase we observe in the myelo-proficient CD150+ HSCs with age. This is consistent with, and could explain, the observation that HSCs isolated from aged mice exhibit a myeloid differentiation bias relative to young HSCs.22 That is, simply a change in the proportions of these subpopulations with age (ie, more CD150+ HSCs) could account for the age-related differentiation bias. Clearly, transplantation experiments specifically designed to address this question are needed to support this idea. Likewise, the increase in myelo-proficient CD150+ HSCs with age may be relevant to the increase in myelodysplasias and myeloproliferative syndromes with age.

Finally, the discovery that CD150− HSCs are capable of giving rise to CD150+ HSCs can be interpreted as providing further evidence for a clonal stability model of HSC maintenance.23,24 Unlike the clonal succession model, in which HSCs are called on to proliferate and become extinguished, the clonal stability hypothesis argues that once an HSC undergoes a period of proliferation, the cell then returns to quiescence for subsequent rounds of blood contribution. Our data support the concept that the more proliferative CD150− HSCs are capable of returning to a phase of relative quiescence as a CD150+ HSC. In fact, our data indicate 2 discrete populations of SPKLS cells, one proliferative and one quiescent, between which HSCs can transition after being transplanted to irradiated recipients. In addition, although our data show a trend toward preferential reconstitution of donor HSC type (ie, CD150+ HSCs generate a greater proportion of CD150+ HSC in recipients), these data are not statistically significant. Thus, the question of whether a hierarchical relation exists between CD150+ and CD150− HSCs remains an open one, and single-cell transplantation experiments will be required to dissect these relationships in more detail. A molecular comparison of CD150+ and CD150− HSCs may suggest a mechanism that distinguishes these states.

Overall, our work shows that, given appropriate and careful application, both the SLAM- and SP-based HSC purification schemes can be used to isolate highly overlapping populations (Figure 7). We have observed long-term HSC activity within the shared overlap of these 2 isolation schemes and within a second population defined as CD150− SPKLS cells. We observed no stem cell potential in the fraction of SLAM cells found outside the SP (termed non-SP), a population of cells which can be largely eliminated with the use of stringent CD150 gating or addition of other canonical stem cell markers such as Sca-1 and c-Kit. Finally, CD150 expression can be used to distinguish less-proliferative LT-HSCs from a more proliferative CD150− LT-HSCs that, although contributes equally to peripheral blood, engrafts the bone marrow at a lower frequency.

SPKLS cells and SLAM cells are functionally overlapping populations. Non-SP cells can be found in significant numbers within the SLAM isolation scheme (particularly when using isotype controls to define the population), and these non-SP cells are not functional HSCs. Further, CD150− cells can be found within the SPKLS sort scheme. The gray area represents populations containing LT-HSC activity, with the darker gray central area representing the less proliferative myeloid-biased LT-HSCs. The area within the Venn diagram is roughly representative of the degree of overlap, but not precisely to scale.

SPKLS cells and SLAM cells are functionally overlapping populations. Non-SP cells can be found in significant numbers within the SLAM isolation scheme (particularly when using isotype controls to define the population), and these non-SP cells are not functional HSCs. Further, CD150− cells can be found within the SPKLS sort scheme. The gray area represents populations containing LT-HSC activity, with the darker gray central area representing the less proliferative myeloid-biased LT-HSCs. The area within the Venn diagram is roughly representative of the degree of overlap, but not precisely to scale.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants T32 DK64717 and T32 GM008307 (D.C.W.), T32 AG000183 (S.M.C.), and DK58192, HL08100, and EB005173. M.A.G. was a Stohlman Scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: D.C.W. and S.M.C. designed and performed experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; N.C.B. performed experiments and helped write the paper; and M.A.G. helped design experiments and write the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Margaret A. Goodell, Stem Cells and Regenerative Medicine Center, One Baylor Plaza, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: goodell@bcm.edu.

References

Author notes

D.C.W. and S.M.C. contributed equally to this study.