The persistence of serum IgG antibodies elicited in human infants is much shorter than when such responses are elicited later in life. The reasons for this rapid waning of antigen-specific antibodies elicited in infancy are yet unknown. We have recently shown that adoptively transferred tetanus toxoid (TT)–specific plasmablasts (PBs) efficiently reach the bone marrow (BM) of infant mice. However, TT-specific PBs fail to persist in the early-life BM, suggesting that they fail to receive the molecular signals that support their survival/differentiation. Using a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL)– and B-cell activating factor (BAFF) B-lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS)–deficient mice, we demonstrate here that APRIL is a critical factor for the establishment of the adult BM reservoir of anti-TT IgG-secreting cells. Through in vitro analyses of PB/plasma cell (PC) survival/differentiation, we show that APRIL induces the expression of Bcl-XL by a preferential binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans at the surface of CD138+ cells. Last, we identify BM-resident macrophages as the main cells that provide survival signals to PBs and show that this function is slowly acquired in early life, in parallel to a progressive acquisition of APRIL expression. Altogether, this identifies APRIL as a critical signal for PB survival that is poorly expressed in the early-life BM compartment.

Introduction

The limitations of antibody responses that may be elicited early in life contribute to high morbidity and mortality from infectious diseases among young children. It has long been recognized that infant IgG responses following natural infection or immunization are weaker than those elicited at a later stage of immune maturation.1,,,,,,,,–10 Moreover, the persistence of IgG generated before 1 year of age is shorter than when such responses are elicited later.11,,,–15 This early waning of IgG may result in a resurgence of vulnerability to infection,15,16 unless vaccine boosters are given in the second year of life. The reasons for this rapid waning of antigen-specific antibodies elicited in infancy are unknown

Serum IgGs are produced by antigen-specific B cells that have undergone activation, proliferation, IgM to IgG switch, selection, and differentiation within germinal centers (GCs). This process generates a subset of post–germinal center B cells that are committed to the plasma cell fate (ie, express Blimp-1 and secrete antigen-specific Ig).17,18 Referred to as plasmablasts (PBs), they are not yet in the G0/G1 phase and exhibit surface markers of both mature B cells and plasma cells (PCs: B220low, CD19+, CD138+).19,–21 These cells undergo final differentiation into PCs that secrete such high amounts of antibodies that serum antibody levels may be maintained by a small population of antibody-secreting cells (ASCs).20 As the half-life of IgG molecules in serum is only 3 weeks, the maintenance of serum antibody levels requires the persistence of ASCs.

There is strong evidence that the longevity of PCs is regulated by their environment19 (ie, their access to survival niches). At the exit of GCs, PBs express CXCR4 and respond to CXCL12 by migration toward environmental niches22,,–25 primarily located within the bone marrow (BM),26 where they receive additional signals required for their differentiation into long-term surviving PCs.17 The role of these long-lived PCs, versus memory B cells, in the maintenance of antibody titers was recently demonstrated in Cr2-deficient mice.27 The characteristics of BM PC niches (ie, cell types, size, accessibility, ontogeny, dynamics, etc) are still poorly defined.28 Recent work demonstrated that BM IgG+ PCs are in direct contact with BM stromal cells (BMSCs) expressing VCAM-1 and CXCL12.29 Factors contributing to the maintenance of BM PCs include CXCL12, interleukin (IL)-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, CD44 ligands, B cell–activating factor/B-lymphocyte stimulator (BAFF/BLyS), and a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL).30,–32 In contrast to the factors contributing to the maintenance of PCs, little is known on the cells and factors required to support the short but critical transition stage during which apoptosis-prone PBs must survive and undergo terminal differentiation into PCs.

Using neonatal murine immunization models that reflect to a large extent the human immune maturation process observed in neonates and infants,33,–35 we observed that the establishment of the BM pool of ASCs is delayed and deficient in early life.36 Even the repeat administration of immunogens eliciting adultlike secondary responses in the spleen of infant mice was not followed by the successful establishment of specific ASCs in the BM.37 This reflects limitations that do not affect neonatal B cells but the BM compartment. Indeed, adoptively transferred spleen PBs generated in neonates or in adults efficiently reach the early-life BM compartment.38 Most PBs transferred into adult recipients persist in the BM, whereas most (70%) PBs reaching the early-life BM compartment disappear within 30 hours, undergoing a significantly higher rate of apoptosis.38 This limited persistence of PBs in the early-life BM compartment results from impaired support provided by early-life BMSCs. Here we defined cellular and molecular factors that support the survival of IgG PBs and that differ in the early and adult BM compartments.

Methods

Mice

BALB/cByJ and C57BL/6 J mice (8-16 weeks) were purchased from Charles River (L'Arbresle, France), bred, and kept under specific pathogen-free conditions. APRIL−/− and BAFF−/− mice were gifts from Genentech (San Francisco, CA) and BiogenIdec (Cambridge, MA), respectively. Manipulations were carried out according to Swiss and European guidelines, and all experiments were approved by the Geneva Veterinary Office.

Antigens, adjuvants, and immunizations

BALB/c mice were immunized twice intraperitoneally at a 3-week interval with TT (1 limit of flocculation per mouse; gift of Berna Biotech, Bern, Switzerland) absorbed to Al(OH)3 (gift of Chiron, Siena, Italy). C57Bl/6 mice were primed with TT/Al(OH)3 with added CpG1826 oligonucleotides (50 μg)39 and boosted with TT-Al(OH)3 5 weeks after priming.

Expression constructs and transfection

For fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), supernatants of HEK-293T cells transiently transfected with Flag-ACRP-mAPRIL A88, Flag-ACRP-mAPRIL H98, Flag-BAFF, or Flag-4–1BBL were used. For survival experiments, Flag-ACRP-mAPRIL H98, Flag-mBAFF, and control Flag-EDA2 molecules were from Apotech/Axxora (Epalinges, Switzerland). Flag-ACRP-mAPRIL A88 was produced as previously described.40

BMSC cultures and plasmablast survival assays

Unless otherwise indicated, BMSC cultures (BMSCCs) were prepared as previously described38 from BALB/c mice. At confluence (day 7-8), supernatants were collected and cells lysed with TRIZOL (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Survival assays were performed as described.38 In other experiments, PBs were incubated in presence of APRIL A88, truncated APRIL H98, BAFF, or EDA-2 as a control for 48 hours. PBs were recovered at time 0 or after 48 hours of culture for enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISpot) assay and survival rates were calculated as follows: percentage of surviving ASCs = surviving ASCs/total ASCs × 100, where total ASCs was 1007 (± 394; mean ± SD) depending on culture. PBs were recovered at time 0 or after 48 hours of culture for FACS analyses or after 24 hours for RNA extraction.

FACS staining

For staining of PBs before and 48 hours after culture, recovered cells were incubated with 20% of 2.4G2 (anti-Fc) supernatant and then stained with anti-B220 (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) and anti-CD138. Propidium iodide exclusion was performed to analyze live cells. For binding experiments, PBs were incubated with 20% of 2.4G2 supernatant and stained with various Flag-molecules. After washing and staining with biotin anti–flag M2 antibody, detection was performed with streptavidin-Alexa 488 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Cells were analyzed using the FACScan (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA) and CellQuest software (BD Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA).

Detection of survival factors

Supernatants of BMSCCs were harvested at days 1 and 5 and after 48 hours of BMSC/PB coculture. The presence of survival factors was assessed by sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) using relevant antibody pairs (clones MP5-20F3 and MP5-32C11 [Pharmingen] for IL-6; clones 5A8 and 1C9 [Apotech/Axxora] for BAFF). Detection limits were 250 pg/mL (IL-6) and 1 ng/mL (BAFF).

In vivo plasmablast transfer

C57BL/6 adult mice were primed and boosted as described in “Antigens, adjuvants, and immunizations.” Four days after boosting, splenocytes were treated with ACK lysis buffer and 108 cells transferred intravenously to recipient mice. Eighteen and 48 hours later, spleen and BM were recovered for evaluation of TT-specific IgG ASCs by ELISpot. To calculate the total number of ASCs in the BM, the number of ASCs/million cells was multiplied by the number of cells recovered from both femurs and tibias and by a coefficient of 5.3.41 Sera from transferred APRIL−/−, BAFF−/−, and C57Bl/6 mice were taken at different time points after transfer and TT-specific antibody titers determined by ELISA as previously described.39

APRIL immunostaining

Day-5 stromal cells were replated in 8-chamber culture slides (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA), at 5 × 104 cells/chamber. One day after, cells were fixed in 1:1 methanol-acetone mix, preincubated with anti–mouse IgG-HRP and rabbit IgG to reduce background, and stained overnight with control or anti-APRIL hybridoma supernatants (IIID3; Apotech/Axxora). Revelation was performed using anti–mouse IgG-Alexa (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) and DAPI staining. Alternatively, cells were stained by biotin-conjugated anti–Mac-1 (M5/70) antibody, revealed by Qdot605-streptavidin (Invitrogen), and coverslip was fixed with polyvinyl alcohol mounting medium with DABCO (Fluka, Munich, Germany). Sections were visualized and photographed with a Zeiss LSM510 Meta confocal microscope (objectives: Plan Neofluar 20×/0.5 and 40×/1.3 oil) at room temperature, and images were acquired with Zeiss LSM image browser software (Zeiss, Feldbach, Switzerland).

Real-time quantitative PCR

Total cellular RNA of fresh BM or BMSCC was isolated and cDNA synthesized as previously described.38 Total cellular RNA from PBs was isolated by RNeasy microkit and 2-step amplification performed following supplier's instructions (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) to obtain cRNA. cDNA was synthesized as previously described.38 Sybr green assays and amplicons were designed as previously described.38 The efficiency of each design was tested with serial dilutions of cDNA and found to be more than 90% for all primer pairs. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reactions were performed on a SDS 7900 HT instrument (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in 3 replicates, with EEF and TBP as internal controls genes for data normalization.42 The following primers (Invitrogen) were used: IL-6–forward 5′-CTATGAAGTTCCTCTCTGCAAGAGACT-3′ and IL-6–reverse 5′-GGGAAGGCCGTGGTTGTC-3′, BAFF-forward 5′-CCGCGGCCACAGGAA-3′ and BAFF-reverse 5′-TGAGAGGTCTACATCTTGTTCTGTTTC-3′, APRIL-forward 5′-TTTCACAATGGGTCAGGTGGTA-3′ and APRIL-reverse 5′-AGGCATACTTCTGATACATCGGAAT-3′, Bcl-XL–forward 5′-CTGGGACACTTTTGTGGATCTCT-3′ and Bcl-XL–reverse 5′-AAGCGCTCCTGGCCTTTC-3′, Blimp-1–forward 5′-GTGCAGAGGTGAGGGTGTGTAG-3′ and Blimp-1–reverse 5′-GCCATCAAATGCGACTGGAT-3′, EEF1A1-forward 5′-TCCACTTGGTCGCTTTGCT and EEF1A1-reverse 5′-CTTCTTGTCCACAGCTTTGATGA-3′, and TBP-forward 5′-TTGACCTAAAGACCATTGCACTTC-3′ and TBP-reverse 5′-TTCTCATGATGACTGCAGCAAA-3′. Normalization factors and relative RNA expression were calculated according to geNorm (http://medgen.urgent.be/∼jvdesomp/genorm/) as previously described.42

Statistical analysis

Statistical differences between 2 groups were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U test, and differences between multiple groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey multiple comparison test. Differences with probability values more than .05 were considered insignificant.

Results

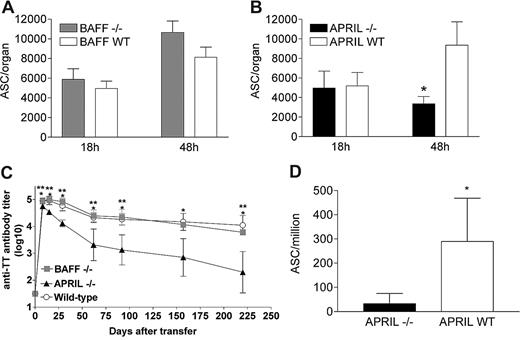

APRIL, but not BAFF, is critical for PB survival in vivo

The demonstrated importance of APRIL and BAFF/BLyS for the generation of PCs prompted us to assess their role in early and adult life, using our previously validated adoptive transfer experiments.38 In this model, splenic PBs generated in adult mice immunized with TT-Al(OH)3 are harvested at the peak (day 4) of the booster response and transferred intravenously prior to their quantification in the BM early (18 hours) or late (48 hours) after transfer. The number of ASCs that reached the BM at 18 hours allows the quantification of in vivo homing, whereas ASCs recovered at 48 hours reflect PB survival in the BM compartment.38 We postulated that if the limited expression of APRIL or BAFF/BLyS by BM cells was critical for PB survival into the BM, a similar pattern of normal homing but limited survival should be observed in infant WT mice and in adult APRIL−/− or BAFF−/− mice.

The pattern of PB survival in vivo was thus assessed into adult BAFF−/−, APRIL−/−, or wild-type C57Bl/6 mice. Similar numbers of TT-specific ASCs were observed in the BM of WT C57Bl/6 and BAFF−/− mice 18 hours and 48 hours after transfer (Figure 1A), indicating that BAFF is not required for early PB survival in vivo. Similar numbers of TT-specific ASCs were also observed in the BM of WT C57Bl/6 and APRIL−/− mice (18 hours) after transfer, indicating similar BM homing. In contrast, TT-specific ASCs recovered 48 hours after transfer from the BM of APRIL−/− mice were significantly (3-fold) fewer than in WT mice (Figure 1B). No difference was observed in the spleen between C57Bl/6, BAFF−/−, or APRIL−/− mice at any time point (not shown). Serum TT-specific IgG titers remained significantly lower in adult APRIL−/− than in C57BL/6 or BAFF−/− mice up to the last time point assessed (Figure 1C), confirming the limited capacity of the BM compartment of APRIL−/− mice to support PB survival/differentiation. The role of APRIL in PB survival/differentiation was confirmed by the immunization of APRIL−/− and WT mice, followed by the quantification of ASCs early (day 7) after boosting. The lower recovery of TT-specific ASCs in the BM of immunized adult APRIL−/− compared with WT mice (Figure 1D) confirmed that APRIL, but not BAFF, is critical for PBs to establish themselves as IgG-producing BM PCs.

APRIL is critical for the in vivo survival of BM plasmablasts. (A) Adult C57BL/6 mice were primed by intraperitoneal injection of TT/AlOH + CpG1826 and boosted 5 weeks later with TT/AlOH. Four days after boosting, splenocytes were harvested and transferred (100 × 106 per recipient mouse) into adult C57BL/6 BAFF−/− or WT recipients. Eighteen and 48 hours later, mice were killed and TT-specific IgG ASCs quantified by ELISpot in the BM compartment. Results are expressed as ASCs per organ (mean ± SD) obtained in one experiment including 4 mice per group and representing 2 independent experiments. (B) Adult C57BL/6 mice were primed by intraperitoneal injection of TT/AlOH + CpG1826 and boosted 5 weeks later with TT/AlOH. Four days after boosting, splenocytes were harvested and transferred (100 × 106 per recipient mouse) into adult C57BL/6 APRIL−/− or WT recipients. Eighteen and 48 hours later, mice were killed and TT-specific IgG ASCs quantified by ELISpot in the BM compartment. Results are expressed as ASCs per organ (mean ± SD) obtained in one experiment including 4 mice per group and representing 3 independent experiments. *P < .05 versus adult WT mice. (C) In an independent experiment, sera from adoptive transfer recipients C57BL/6 APRIL−/−, BAFF−/−, or WT adult mice were harvested at different time points after transfer and TT-specific antibody titer was determined by ELISA. *P < .05 WT versus APRIL−/−; **P < .05 BAFF−/− versus APRIL−/−. (D) APRIL−/− and C57BL/6 control mice were immunized as described in “Antigens, adjuvants, and immunizations” and TT-specific IgG ASCs were quantified by ELISpot in the BM 7 days after boost. Results are expressed as ASCs per million (mean ± SD) obtained in 2 experiments including 6 to 10 mice per group *P < .05 versus adult WT mice.

APRIL is critical for the in vivo survival of BM plasmablasts. (A) Adult C57BL/6 mice were primed by intraperitoneal injection of TT/AlOH + CpG1826 and boosted 5 weeks later with TT/AlOH. Four days after boosting, splenocytes were harvested and transferred (100 × 106 per recipient mouse) into adult C57BL/6 BAFF−/− or WT recipients. Eighteen and 48 hours later, mice were killed and TT-specific IgG ASCs quantified by ELISpot in the BM compartment. Results are expressed as ASCs per organ (mean ± SD) obtained in one experiment including 4 mice per group and representing 2 independent experiments. (B) Adult C57BL/6 mice were primed by intraperitoneal injection of TT/AlOH + CpG1826 and boosted 5 weeks later with TT/AlOH. Four days after boosting, splenocytes were harvested and transferred (100 × 106 per recipient mouse) into adult C57BL/6 APRIL−/− or WT recipients. Eighteen and 48 hours later, mice were killed and TT-specific IgG ASCs quantified by ELISpot in the BM compartment. Results are expressed as ASCs per organ (mean ± SD) obtained in one experiment including 4 mice per group and representing 3 independent experiments. *P < .05 versus adult WT mice. (C) In an independent experiment, sera from adoptive transfer recipients C57BL/6 APRIL−/−, BAFF−/−, or WT adult mice were harvested at different time points after transfer and TT-specific antibody titer was determined by ELISA. *P < .05 WT versus APRIL−/−; **P < .05 BAFF−/− versus APRIL−/−. (D) APRIL−/− and C57BL/6 control mice were immunized as described in “Antigens, adjuvants, and immunizations” and TT-specific IgG ASCs were quantified by ELISpot in the BM 7 days after boost. Results are expressed as ASCs per million (mean ± SD) obtained in 2 experiments including 6 to 10 mice per group *P < .05 versus adult WT mice.

Binding to proteoglycans confers a preferential PB-supporting activity to APRIL

BAFF and APRIL may bind to both BCMA and TACI, in addition to the binding of BAFF to BAFF-R and of APRIL to proteoglycans.43 To compare the relative capacity of APRIL and BAFF to bind to murine PBs, PBs were incubated with graded concentrations of Flag-APRIL or Flag-BAFF molecules and stained with antiflag monoAb to estimate relative binding capacities. Flag-BAFF and Flag-APRIL similarly bound to adult PBs (MFI 7.5 ± 0.7 and 7.9 ± 2.2, respectively; Figure 2A). As expected, the preincubation of Flag-APRIL with heparin strongly decreased PB binding, suggesting an important role of its interaction with proteoglycans, confirmed by the limited binding of a truncated APRIL molecule (H98) in which the heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG) binding region is deleted44 (Figure 2A).

Similar binding of APRIL and BAFF to plasmablasts but preferential survival support mediated by APRIL. Recombinant trimeric murine molecules were tested for their capacity to (A) bind to PBs and (B) support the recovery of TT-specific ASCs. (A) Purified PBs (2 × 105, isolated by CD138 staining) were incubated with 500 nM of a murine Flag-recombinant molecule (BAFF, APRIL A88, truncated APRIL H98, or control molecule [4–1BB-L]), with or without preincubation with heparin as indicated. The binding to PBs was revealed by antiflag staining. (B) Purified PBs were seeded into 96-well plates (5 × 103 cells/well) in presence of different concentrations of recombinant murine molecules (complete APRIL A88, truncated APRIL H98, BAFF, or EDA-2 control molecule). TT-specific IgG ASCs were enumerated by ELISpot initially and after 48 hours of culture and survival expressed as mean (± SD) of 3 independent cultures. *P < .05 versus PB cultured with the same concentration of control molecule. **P < .05 versus PB cultured with the same concentration of BAFF. ***P < .05 versus PB cultured with same concentration of the truncated APRIL H98. (C) The expression of Bcl-XL and Blimp-1 by PBs was evaluated by quantitative real-time reverse-transcription (RT)–PCR at onset (ex vivo) and after 24 hours of culture with 300 ng/mL of molecule. Results are expressed as the fold change of transcript expression for each condition of culture compared with t0 obtained from 1 representative experiment (pool of 10 mice) of 2.

Similar binding of APRIL and BAFF to plasmablasts but preferential survival support mediated by APRIL. Recombinant trimeric murine molecules were tested for their capacity to (A) bind to PBs and (B) support the recovery of TT-specific ASCs. (A) Purified PBs (2 × 105, isolated by CD138 staining) were incubated with 500 nM of a murine Flag-recombinant molecule (BAFF, APRIL A88, truncated APRIL H98, or control molecule [4–1BB-L]), with or without preincubation with heparin as indicated. The binding to PBs was revealed by antiflag staining. (B) Purified PBs were seeded into 96-well plates (5 × 103 cells/well) in presence of different concentrations of recombinant murine molecules (complete APRIL A88, truncated APRIL H98, BAFF, or EDA-2 control molecule). TT-specific IgG ASCs were enumerated by ELISpot initially and after 48 hours of culture and survival expressed as mean (± SD) of 3 independent cultures. *P < .05 versus PB cultured with the same concentration of control molecule. **P < .05 versus PB cultured with the same concentration of BAFF. ***P < .05 versus PB cultured with same concentration of the truncated APRIL H98. (C) The expression of Bcl-XL and Blimp-1 by PBs was evaluated by quantitative real-time reverse-transcription (RT)–PCR at onset (ex vivo) and after 24 hours of culture with 300 ng/mL of molecule. Results are expressed as the fold change of transcript expression for each condition of culture compared with t0 obtained from 1 representative experiment (pool of 10 mice) of 2.

To compare the relative capacity of APRIL and BAFF to support PB survival, TT-specific PBs were cultured in presence of recombinant ligands, prior to the quantification of TT-specific ASCs. In vitro, both BAFF and APRIL supported the recovery of ASCs (Figure 2B). However, the PB-supporting capacity of APRIL was dose dependent and reached significantly higher levels than that of BAFF. Interestingly, APRIL A88 was more efficient than truncated APRIL H98 (Figure 2B). This reflects the differential binding of APRIL A88 and H98 to HSPG rather than different concentrations of bioactive APRIL in these preparations, as the proliferation of B cells was similarly supported by APRIL H98 and APRIL A88 (Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

BAFF and APRIL were both reported to block B-cell antigen receptor–induced apoptosis upstream of mitochondrial damage, suggesting a role for Bcl-2 family proteins. That APRIL may support PB survival in vitro better than BAFF was confirmed by an enhanced expression of Bcl-XL in PBs incubated with APRIL but not BAFF (Figure 2C). This was not associated with an increase of Blimp-1, indicating no direct influence of APRIL on PB to PC differentiation (Figure 2C). Altogether, these observations confirm that both BAFF and APRIL may support PB survival in vitro but show that the critical advantage of APRIL for PB survival results from its binding to HSPG on PB.

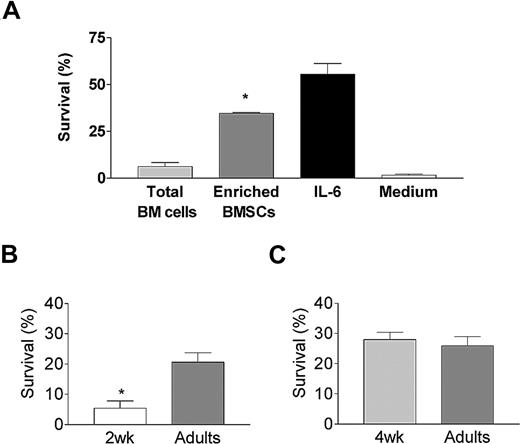

Early-life BMSCs fail to support plasmablast survival

We next used primary BMSCCs to better define the cellular components of the BM niches that support PB survival. Splenic PBs harvested at the peak of the response (ie, day 4 after TT boosting) were cultured ex vivo for 48 hours on a monolayer of enriched BMSCs, generated as previously described,38 prior to the quantification of TT-specific ASCs. The recovery of TT-specific ASCs was markedly (> 6-fold) higher when PBs were incubated on enriched BMSCs than with freshly isolated total BM cells or in medium alone (Figure 3A). This enrichment of the PB-supporting capacity of adult BMSCs was associated with a high proportion of cells defined as nonimmediately adherent, Mac-1+, F4/80+, and Gr-1− cells (Figure S2A,B). CD3+ T cells and B220high B cells were present at percentages less than 10% each. These prominent Mac-1+F4/80+ BMSCs belong to the lineage of “tissue-resident macrophages” since they are CD11cint but CCR2− (Figure S2C). Moreover, all Mac-1+F4/80+ BMSCs expressed MHCII but few expressed VCAM-1 and some displayed an intermediate expression of Thy-1. Thus, BMSCCs with enriched PB-supporting capacity were a heterogeneous population in which resident macrophages were the main cell population.

Ontogeny of the BMSC plasmablast-supporting capacity. (A) The capacity of BM cells to support the recovery of TT-specific ASCs was evaluated in coculture experiments. Fresh total BM cells from 5 individual mice were seeded immediately after harvesting into 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells/well. Enriched BMSCs generated from a pool of 10 10-week-old mice were generated by 5 days of culture as described in “BMSC cultures and plasmoblast survival assay” and reseeded at the same density. TT-specific splenic PBs (5 × 103) purified by anti-CD138 AutoMACS (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) sorting were added 24 hours later. Control wells contained PBs incubated in medium alone or with 10 ng/mL recombinant murine IL-6. TT-specific IgG ASCs were enumerated by ELISpot at the onset and after 48 hours of culture. The proportion of surviving PBs was calculated (recovered TT-specific ASCs/initial TT-specific ASCs × 100) and expressed as the mean (± SD) of 6 independent cultures. *P < .05 versus coculture of PB with adult total BM cells. (B) Similar experiments were performed with enriched BMSCs generated from a pool of fifteen 2- or 10-week-old (control) mice. Results are expressed as the mean (± SD) of 6 independent cultures per age group. One representative experiment of 3 is shown. *P < .05 versus adult enriched BMSCs. (C) Similar experiments were performed with enriched BMSCs generated from a pool of fifteen 4- or 10-week-old (control) mice. Results are expressed as the mean (± SD) of 6 independent cultures per age group. One representative experiment of 3 is shown. Error bars represent SD.

Ontogeny of the BMSC plasmablast-supporting capacity. (A) The capacity of BM cells to support the recovery of TT-specific ASCs was evaluated in coculture experiments. Fresh total BM cells from 5 individual mice were seeded immediately after harvesting into 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells/well. Enriched BMSCs generated from a pool of 10 10-week-old mice were generated by 5 days of culture as described in “BMSC cultures and plasmoblast survival assay” and reseeded at the same density. TT-specific splenic PBs (5 × 103) purified by anti-CD138 AutoMACS (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) sorting were added 24 hours later. Control wells contained PBs incubated in medium alone or with 10 ng/mL recombinant murine IL-6. TT-specific IgG ASCs were enumerated by ELISpot at the onset and after 48 hours of culture. The proportion of surviving PBs was calculated (recovered TT-specific ASCs/initial TT-specific ASCs × 100) and expressed as the mean (± SD) of 6 independent cultures. *P < .05 versus coculture of PB with adult total BM cells. (B) Similar experiments were performed with enriched BMSCs generated from a pool of fifteen 2- or 10-week-old (control) mice. Results are expressed as the mean (± SD) of 6 independent cultures per age group. One representative experiment of 3 is shown. *P < .05 versus adult enriched BMSCs. (C) Similar experiments were performed with enriched BMSCs generated from a pool of fifteen 4- or 10-week-old (control) mice. Results are expressed as the mean (± SD) of 6 independent cultures per age group. One representative experiment of 3 is shown. Error bars represent SD.

To characterize the acquisition of the PB-supporting capacity of BMSCs during ontogeny, PBs were cultured ex vivo on enriched BMSCs generated from 2-week-old, 4-week-old, or adult mice. As previously reported,38 few TT-specific ASCs were recovered when adult PBs were seeded on 2-week-old BMSCs (Figure 3B). In contrast, the proportion of TT-specific ASCs was similar when PBs were cultured on 4-week-old or adult BMSCs (Figure 3C). The limited PB-supporting capacity of BMSCs is thus early-life specific. The proportion of Mac-1+F4/80+ cells was similar (70% to 85%) in 2-week-old and adult BMSCs. (Figure S2B). Thus, the limited PB-supporting capacity of early-life BMSCs does not reflect a delayed ontogeny of Mac-1+F4/80+ cells, but does reflect differences in their functional capacity.

Adult BMSCs might enhance the recovery of TT-specific ASCs by supporting PB proliferation, survival, and/or PC differentiation. Their influence on proliferation was first assessed by adding hydroxyurea, a proliferation-blocking agent,31 during PB culture on adult BMSCs. This did not affect the recovery of TT-specific ASCs (Figure S3A), although it completely blocked the LPS-induced proliferation of splenic B cells (Figure S3B). Accordingly, the analysis of CFSE-labeled PBs did not indicate that cell division occurs during coculture on adult BMSCs. CFSE staining profiles were the same 24 hours or 48 hours after coculture initiation and unaffected by the presence of hydroxyurea (Figure S3C).

The role of BMSCs on PB survival/differentiation was assessed by defining their influence on PB phenotype. Culture of CD138+ cells with adult BMSCs or IL-6 generated more live cells than culture with 2-week-old BMSCs or medium only (Figure 4A), consistent with results of ASC frequencies obtained by ELISpot. A contamination by BMSCs was excluded since PBs recovered after BMSC coculture contained less than 2% of Mac-1+ cells (not shown). The percentage of PBs (CD138intB220int) markedly decreased between time 0 (t0: 42% to 63%) and 48 (5% to 17%) hours after culture, while the proportion of mature B cells (CD138−B220high), prePBs (CD138intB220high), and PBs recovered after 48 hours remained unchanged in the different cultures, confirming that the cultures essentially influence terminal B-cell differentiation (Figure 4B,C). PC differentiation was enhanced by the addition of IL-6, which increased the number of PCs and prePCs (Figure 4B,C) and the expression of Blimp-117,45,46 by CD138+ cells (Figure 4D). Culture on adult BMSCs yielded a higher proportion of live PCs than when PBs were cultured in medium alone or on 2-week-old BMSCs (Figure 4B,C). Thus, adult BMSCs were more potent than 2-week-old BMSCs for supporting the survival/differentiation of PBs/PCs. The distinction between such closely related events is not trivial. However, a marked enhancement of Bcl-XL expression by CD138+ cells, contrasting with the lack of increase of Blimp-1, was observed upon PB culture on enriched adult BMSCs (Figure 4D). In accordance with previous observations,47 this indicates that enriched adult BMSCs essentially support survival. Remarkably, this increase in Bcl-XL expression was not observed when PBs were cultured on 2-week-old BMSCs (Figure 4D), demonstrating their limited capacity to provide sufficient survival signals. Thus, BMSCs directly support PB/PC survival, but this functional capacity is acquired only between 2 and 4 weeks after birth.

Adult enriched BMSCs support plasmablast survival. (A-C) Purified PBs (5 × 103) were added on adult enriched BMSCs or 2-week enriched BMSCs, or incubated with medium or IL-6. (A) The viability of recovered cells was analyzed by FACS 48 hours after culture using propidium iodide exclusion. Results are expressed as the mean (± SD) of 4 independent cultures per condition. *P < .05 versus 2-week enriched BMSCs. **P < .05 versus medium. (B) FACS panels for expression of B220 and CD138 for one culture per each condition representing 4 independent cultures. Percentages of each subset gated on live cells are shown on the plots. (C) Percentage of each subset gated on live cells determined by FACS staining as described in panel A. Results are expressed as the mean (± SD) of 4 independent cultures per each condition. *P < .05 versus 2-week enriched BMSCs. **P < .05 versus medium. (D) The expression of Bcl-XL and Blimp-1 by PBs was evaluated by quantitative real-time RT-PCR at onset (ex vivo) and after 24 hours of culture. Results are expressed as the fold change of transcript expression for each condition of culture compared with t0 (mean ± SD) obtained from 3 independent cultures each representing a pool of 10 mice. *P < .05 versus 2-week enriched BMSCs. **P < .05 versus medium.

Adult enriched BMSCs support plasmablast survival. (A-C) Purified PBs (5 × 103) were added on adult enriched BMSCs or 2-week enriched BMSCs, or incubated with medium or IL-6. (A) The viability of recovered cells was analyzed by FACS 48 hours after culture using propidium iodide exclusion. Results are expressed as the mean (± SD) of 4 independent cultures per condition. *P < .05 versus 2-week enriched BMSCs. **P < .05 versus medium. (B) FACS panels for expression of B220 and CD138 for one culture per each condition representing 4 independent cultures. Percentages of each subset gated on live cells are shown on the plots. (C) Percentage of each subset gated on live cells determined by FACS staining as described in panel A. Results are expressed as the mean (± SD) of 4 independent cultures per each condition. *P < .05 versus 2-week enriched BMSCs. **P < .05 versus medium. (D) The expression of Bcl-XL and Blimp-1 by PBs was evaluated by quantitative real-time RT-PCR at onset (ex vivo) and after 24 hours of culture. Results are expressed as the fold change of transcript expression for each condition of culture compared with t0 (mean ± SD) obtained from 3 independent cultures each representing a pool of 10 mice. *P < .05 versus 2-week enriched BMSCs. **P < .05 versus medium.

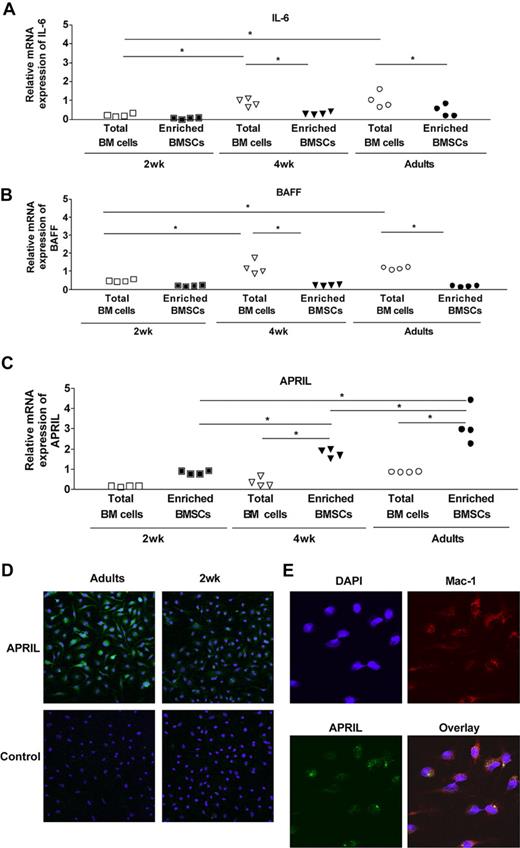

Early-life BMSCs fail to express adult levels of APRIL

We next asked whether the support of PB survival conferred by BMSCs was mediated by BAFF/BLyS, APRIL, or IL-6, known to contribute to PC survival.30,–32 IL-6 mRNA was present at very low levels in BM cells ex vivo (total BM cells, Ct = 31.8 ± 0.4), on day 6 of culture or after 48 hours of coculture with PBs (Ct = 33.06 ± 1.4, Figure 5A). Accordingly, IL-6 concentration remained below detection level in BMSCC supernatants (not shown). IL-6 is therefore not required for PB survival in our experimental system. BAFF mRNA was strongly expressed ex vivo in total adult BM cells (Ct = 25.5 ± 0.6, Figure 5B). However, BMSCCs expressed only low levels of BAFF (Ct = 28.4 ± 0.6, Figure 5B), which remained below detection level when assessed by ELISA (not shown). In contrast, the expression of APRIL mRNA was much higher in adult BMSCCs (Ct = 23.8 ± 0.5) than ex vivo in total BM cells (Ct = 25.5 ± 0.6, Figure 5C). The availability of a novel antimurine APRIL hybridoma supernatant whose reactivity is negative on control APRIL−/− cells (Figure S4A) allowed to confirm APRIL protein expression by adult enriched BMSCs (Figure 5D). Confocal microscopic analyses confirmed Mac1+ cells as the main APRIL-producing BMSCs (Figure 5E). Western blot analyses (not shown) and FACS staining (Figure S4B) were not sufficiently sensitive to detect baseline APRIL expression in BMSCs.

Delayed ontogeny of APRIL expression by BM cells. The expression of mRNA IL-6 (A), BAFF (B), and APRIL (C) was evaluated by quantitative real-time RT-PCR on fresh BM cells and on BMSCs from 2-week-old, 4-week-old, and adult mice. Results include data generated with a pool of 6 to 7 individual mice (total BM cells) or 5 independent cultures of a pool of 10 mice (enriched BMSCs). *P < .05. (D) BMSCs (5 × 104) from adult and 2-week-old mice were stained in chamber slides with IIID3 antibody as described in “APRIL immunostaining.” (E) BMSCs (5 × 104) from adult mice were stained in chamber slides with IIID3 antibody and anti–Mac-1 antibody as described in “APRIL immunostaining.”

Delayed ontogeny of APRIL expression by BM cells. The expression of mRNA IL-6 (A), BAFF (B), and APRIL (C) was evaluated by quantitative real-time RT-PCR on fresh BM cells and on BMSCs from 2-week-old, 4-week-old, and adult mice. Results include data generated with a pool of 6 to 7 individual mice (total BM cells) or 5 independent cultures of a pool of 10 mice (enriched BMSCs). *P < .05. (D) BMSCs (5 × 104) from adult and 2-week-old mice were stained in chamber slides with IIID3 antibody as described in “APRIL immunostaining.” (E) BMSCs (5 × 104) from adult mice were stained in chamber slides with IIID3 antibody and anti–Mac-1 antibody as described in “APRIL immunostaining.”

The comparative expression of IL-6, BAFF, and APRIL was assessed in 2-week-old, 4-week-old, and adult BM cells. IL-6 expression remained weak in all samples (Figure 5A). In the total BM cell population, the expression of BAFF increased during ontogeny (Figure 5B). However, BAFF was as weakly expressed by day-6 BMSCs generated in early life as in those from adult controls. In contrast, the expression of APRIL mRNA was significantly higher in 4-week-old or adult BMSCs than in 2-week-old BMSCs (Figure 5C). This was associated with a stronger protein expression of APRIL in adult BMSCs than in 2-week-old BMSCs (Figure 5D). APRIL expression was assessed ex vivo in Mac-1+Gr1low cells sorted from the BM of adult and 2-week-old mice (mean relative mRNA expression: 1.60 vs 0.42, respectively), confirming the limited expression of APRIL by early-life BM-resident Mac-1+ cells. Despite the insufficient sensitivity of current protein detection assays, the direct correlation between PB-supporting capacity and the expression of APRIL mRNA strongly suggests that the limited expression of APRIL by early-life BMSCs is insufficient to provide optimal PB survival signals.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that the transition of antigen-specific splenic IgG plasmablasts into ASCs that survive in the BM compartment is a critical stage that requires the expression of APRIL by BMSCs and its interaction with HSPG at the PB surface. It establishes that this process is inefficient in early life, limiting the establishment of the BM PC pool.

To study the terminal differentiation of in vivo–generated PBs, we took advantage of the synchronization of secondary responses that may be achieved by booster immunization. Pilot experiments indicated that on day 4 after boost with a strong immunogen (TT) adsorbed to alum, more than 90% of splenic IgG-secreting cells are TT-specific PBs capable of migrating toward CXCL1238 or the BM compartment.38 Using this physiological source of Ag-specific PBs, we observed that PBs rapidly die ex vivo unless they receive specific support from BMSCs, and investigated which cell types mediate this support. Recent studies established that BM IgG+ PCs are in contact with VCAM+- and CXCL12+-expressing BMSCs.29 Phenotypic analyses indicated that these BMSCs belong to fibroblast-like reticular cells29 that may be enriched by Whitlock-type long-term BM cultures and support the maintenance of murine PC longevity30 or the final differentiation of human blood–derived or BM-derived early PCs.48,–50 Such BMSCs represent a heterogeneous population. In our hands, freshly isolated total murine BM cells provided very little PB support (Figure 3A). In contrast, culture conditions optimized to enhance the recovery of nonimmediately adherent Mac1+, F4/80+, Gr-1− cells (Figure S2) reliably lead to a marked increase of the survival of TT-specific PBs. These cells belong to the hematopoietic lineage, and more specifically to BM-resident macrophages. We cannot exclude that another minor population could also have PB-supporting capacity since the low yield of BMSCs did not allow to recover enough cells with more than 90% purity from other populations. However, the parallel increase of the number of BM-resident macrophages and of the PB-supporting capacity suggests that they are an important component of the PB-supporting hematopoietic BM niches.

BMSCs might support antigen-specific ASCs by enhancing ex vivo PB proliferation However, the use of a proliferation-blocking agent and the tracking of PB divisions (Figure S3) indicated that TT-specific PBs do not proliferate when cultured on BMSCs. Adult BMSCs did not significantly enhance the PB expression of Blimp-1, which regulates Ig secretion and the final differentiation of PBs into PCs.45 In contrast, adult BMSCs induced a significant increase in antiapoptotic gene (Bcl-XL) expression (Figure 4), which was associated with a high level of surviving CD138+ cells, in particularly PCs. Altogether, this demonstrates that BMSCs essentially support PB survival, enabling the surviving cells to undergo their differentiation into PCs under the influence of additional signals such as IL-6 (Figure 4). This is in accordance both with the proapoptotic state of PBs51 and the role of Bcl-xL in mediating PC survival.47,52

Factors identified as supporting the survival of PCs include CXCL12, IL-6, BAFF/BLyS, and APRIL. We previously reported the similar CXCL12-mediated homing of PBs to the early life and adult BM,38 and thus focused here on IL-6, BAFF/BLyS, and APRIL. Whitlock-derived BM stromal cell lines support PC survival and differentiation in an IL-6–dependent manner.31 The exogenous addition of IL-6 supports the recovery of TT-specific ASCs, in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3 and data not shown). However, IL-6 was weakly expressed in total BM cells and did not increase in day-6 BMSCCs despite a marked enrichment in PB-supporting function. Coculture with PBs31,53 did not increase IL-6 expression by BMSCs. Accordingly, IL-6 is not required for the establishment of the BM PC pool in vivo, as demonstrated in IL-6−/− mice.31 Altogether, this suggests that IL-6 essentially supports PB differentiation into PCs, as evidenced by its influence on Blimp-1 expression (Figure 4), whereas other molecules are critical for PB survival.

The implication of BAFF/BLyS and APRIL in PC survival was recently established.32,44,54,55 These 2 TNF family ligands that share many characteristics may be expressed by a large series of cells (monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, neutrophils, T cells, osteoclasts, BMSCs, and nurselike cells).43 The depletion of both BAFF and APRIL, by the administration of the TACI-Ig decoy receptor or through the genetic invalidation of the BAFF/APRIL-binding BCMA receptor, depletes the BM PC pool.32 Although these ligands are critical players in the maintenance of PCs, their respective contribution remains to be defined.43 BAFF and APRIL enhance the ex vivo survival of PBs generated in vitro from human memory B cells.56 Their influence on recently generated in vivo PCs was recently addressed by treating mice on day 6 after immunization with either BCMA:Fc or BAFF-R:Fc.44 The frequency of BM antigen-specific PCs was dramatically decreased only in mice treated with BCMA:Fc, strongly suggesting the importance of APRIL (either alone or with BAFF) for the migration and/or the survival of BM-resident PCs.44

Our results demonstrate that although both BAFF and APRIL bind to PBs and support their survival ex vivo, APRIL exerts a critical role (Figure 2). The expression of APRIL, but not that of BAFF, parallels the increase in the PB-supporting capacity of adult BMSCs (Figure 5). Furthermore, the transfer of TT-specific PBs in BAFF−/− mice demonstrates that BAFF does not play a critical role in supporting PB survival in vivo (Figure 1A). In contrast, the same transfer in APRIL−/− mice formally demonstrates that despite normal homing TT-specific PBs fail to establish efficiently as persisting ASCs in the BM compartment of APRIL−/− mice (Figure 1B), which results into a shorter persistence of serum TT-specific IgG titers (Figure 1C). In a more physiological immunization model, the significantly lower number of TT-specific ASCs in the BM compartment of APRIL−/− adult mice early after boosting confirms that the absence of APRIL is sufficient to markedly limit the establishment of the BM ASC pool (Figure 1D).

These results are the first to directly decipher the distinct roles of APRIL and BAFF in PB survival in vivo. The frequency of antigen-specific BM ASCs was dramatically reduced when BAFF and APRIL (but not of BAFF alone) were blocked by BCMA-Ig administration one week after immunization.44 This in accordance with a main role of APRIL on PB rather than PC survival. Interestingly, the number of total IgG-producing BM ASCs is similar in adult APRIL−/− (60 × 103/mouse) and WT (35 × 103/mouse) mice, explaining why the PB-supporting function of APRIL was not identified earlier.57,58 The same is true for IL-6−/− mice, which have normal numbers of PBs/PCs in their BM despite evidence for the role of IL-6 in PC differentiation.31 This could reflect the implication of yet-unidentified PB/PC survival/differentiation factors. Alternatively, some PBs may escape from apoptosis and survive long enough to terminally differentiate into PCs that slowly accumulate in the BM, supported by PC survival factors. Thus, APRIL-blocking strategies currently considered for use in autoimmune conditions43 may have a greater impact on recently generated PBs than on successfully established long-lived PCs.

How may the relative contribution of APRIL and BAFF to PB survival be so distinct? Despite many common characteristics, APRIL and BAFF show considerable differences with respect to receptor binding. BAFF binds to BAFF-R, BCMA, and TACI, whereas APRIL binds to BCMA, TACI, and proteoglycans.43,59 As B-cell differentiation proceeds toward PBs and PCs, the expression of TACI and of BAFF-R decreases, whereas that of BCMA increases.43 Biacore studies using recombinant ligands and receptor-Fc fusion proteins have indicated that APRIL binds with much higher affinity to monomeric BCMA than BAFF does, although this difference in no longer seen with dimeric BCMA-Ig,60 suggesting a potential predominance of the APRIL-BCMA axis. In addition, HSPGs were described as APRIL-specific binding partners,44,61 and syndecan-1+ PCs display a highly specific binding of APRIL sensitive to inhibition by heparin.44 We observed that TT-specific PBs bind to APRIL in a heparin-blocking manner, with a residual staining attributed to BCMA and/or TACI binding (Figure 2). Binding of APRIL to PB HSPGs likely contributes to promote PB survival, because a truncated H98 APRIL molecule deprived of the basic sequence (QKQKKQ) responsible for HSPG binding is less efficient.44 Remarkably, proteoglycans (such as Syndecan-1) are expressed at increasingly high levels as Blimp-1–regulated B-cell differentiation progresses toward differentiated PCs. HSPG may convert soluble proteins into a 2-dimensional array that enhances further molecular encounters,62 protect ligands from degradation, or support further oligomerization.63 The binding of APRIL to HSPG may thus be a prerequisite for signaling through BCMA (or possibly TACI) molecules expressed at the PB/PC stage.56 Thus, the yet elusive biologic purpose for APRIL binding to HSPG43 may be to support PB survival at a transient—but critical—stage of their differentiation into PCs.

The physiological importance of APRIL expression by BMSCs for PB survival in the BM compartment is further evidenced by the identification of a physiological situation during which this process is impaired. We previously reported that the establishment of the BM ASC pool is delayed and limited in infant BALB/c mice37 and that this reflects the limited survival of PBs reaching the early-life BM.38 Here, we show that several weeks2,–4 of postnatal maturation are required for the BM to provide an adultlike PB support. Given the rapid kinetics of the postnatal maturation of murine secondary lymphoid organs, this maturation process is remarkably slow. The only molecular difference currently identified between PB-supporting adult BMSCs and non–PB-supporting BMSCs generated from infant mice is that of a limited expression of APRIL. Formal evidence that APRIL is the critical factor that limits the establishment of the BM ASC pool in early life is difficult to generate. However, the demonstration that adult PBs survive similarly poorly when transferred into the BM compartment of WT infant mice and of APRIL−/− mice, and that APRIL expression is the only currently identified factor better expressed by adult PB-supporting than infant non–PB-supporting BMSCs are strong arguments in support of a critical role for APRIL. We do not yet know whether the extensive similarities previously demonstrated in early-life murine and human IgG responses will extend to include limitations of the same BM-derived PB survival factors. Should this prove to be the case, the rapid waning of antigen-specific antibodies elicited in early human life and the associated resurgence of vulnerability to infections could remain a challenge difficult to meet without booster immunizations.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Paolo Quirighetti for assistance with animal care; Karine Ingold for technical support; Martin Scott from BiogenIdec for making BAFF−/− mice available; Christine Brighouse for secretarial support; and Mylène Docquier and the Genomics Platform of the National Center of Competence in Research program Frontiers in Genetics for assistance with the real-time PCR.

This work was supported by a grant from the Swiss National Research Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: E.B., M.P., T.L.M., P.S., B.H., P.-H.L., and C.-A.S. designed research; E.B., M.P., T.L.M., C.T., A.-F.R., and C.B. performed research; E.B., M.P., and T.L.M. analyzed data; P.S., B.H., and P.-H.L. provided helpful discussions; and E.B. and C.-A.S wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Claire-Anne Siegrist, World Health Organization Collaborating Center for Vaccinology and Neonatal Immunology, Departments of Pathology-Immunology and Pediatrics, University of Geneva, CH-1211 Geneva 4, Switzerland; e-mail: claire-anne.siegrist@medecine.unige.ch.

References

Author notes

E.B. and M.P. contributed equally to this work.

![Figure 2. Similar binding of APRIL and BAFF to plasmablasts but preferential survival support mediated by APRIL. Recombinant trimeric murine molecules were tested for their capacity to (A) bind to PBs and (B) support the recovery of TT-specific ASCs. (A) Purified PBs (2 × 105, isolated by CD138 staining) were incubated with 500 nM of a murine Flag-recombinant molecule (BAFF, APRIL A88, truncated APRIL H98, or control molecule [4–1BB-L]), with or without preincubation with heparin as indicated. The binding to PBs was revealed by antiflag staining. (B) Purified PBs were seeded into 96-well plates (5 × 103 cells/well) in presence of different concentrations of recombinant murine molecules (complete APRIL A88, truncated APRIL H98, BAFF, or EDA-2 control molecule). TT-specific IgG ASCs were enumerated by ELISpot initially and after 48 hours of culture and survival expressed as mean (± SD) of 3 independent cultures. *P < .05 versus PB cultured with the same concentration of control molecule. **P < .05 versus PB cultured with the same concentration of BAFF. ***P < .05 versus PB cultured with same concentration of the truncated APRIL H98. (C) The expression of Bcl-XL and Blimp-1 by PBs was evaluated by quantitative real-time reverse-transcription (RT)–PCR at onset (ex vivo) and after 24 hours of culture with 300 ng/mL of molecule. Results are expressed as the fold change of transcript expression for each condition of culture compared with t0 obtained from 1 representative experiment (pool of 10 mice) of 2.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/111/5/10.1182_blood-2007-09-110858/2/m_zh80060816410002.jpeg?Expires=1767731895&Signature=t1Qd4BvXtXOezFbic~92dq1bAH9Lg7WiSN0lHCQR-PbjgnvCnZl40-itH04Bc5ruJypYR5aSbiuCWd4fX21NDsXV12MpfruS3fPQ-6GzzeGd0OYaO7jX-ohYZophFgfWIhYYDq6RwWieo998WtJIpTLQqTC3fObUf7REhFOZNLuaB01tV1RdBhk3Ig6H~fJNL-HdOL8CxC4v~2SRS6rzKJmuYS5aw7MduFUy4Ubcy30a4ZGYUMjShZSN5W3AiK9N6Py84GBHlJ3OS5MILv52jt1oQ0l7KDU3QhrnJIjY62-FR4-anpN0aKaI39L-AWvy7GyGaVtD2G0oUbqIrapyeg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)