Much has been learned about the dynamics of platelet biogenesis. However, the dynamics of the cytoskeletal engine in live platelets have not been thoroughly investigated until recently.

In this issue of Blood, a report by Patel-Hett and colleagues, led by Joseph Italiano, focuses on platelet intracellular dynamics, providing us with the first visualization of a cytoskeletal engine in live platelets. This elegant study reveals a marginal band with multiple actively polymerizing microtubules.

Since its discovery by Behnke and White in the late 1960s, the marginal band has been recognized as a structure essential to maintaining the discoid shape of platelets.1,2 Classic electron microscopy studies over the past 40 years have suggested that the marginal band is composed of a single, inactive microtubule coiled 8 to 12 times, forming concentric rings around the platelet perimeter.3 To date, this model, as well as our view of the entire platelet cytoskeletal machinery, has relied solely on micrographs of chemically fixed cells. A dynamic cytoskeleton could account for many of the physiological properties of platelets. However, direct visualization of platelet cytoskeletal dynamics has been hampered by the small size of platelets and their lack of a nucleus, making microinjection and genetic manipulation intractable. To visualize microtubule dynamics, Patel et al retrovirally expressed the microtubule-plus-end marker EB3-green fluorescent protein (GFP) in megakaryocytes and examined its behavior in platelets released from these cells.4 Fluorescence time-lapse microscopy of EB3-GFP, which resembles a comet as it streaks through the cell, revealed that the platelet marginal band in resting platelets is composed of at least 8 dynamic microtubules. The authors used both immunofluorescence and a permeabilized platelet system to confirm the presence of multiple marginal band microtubules.

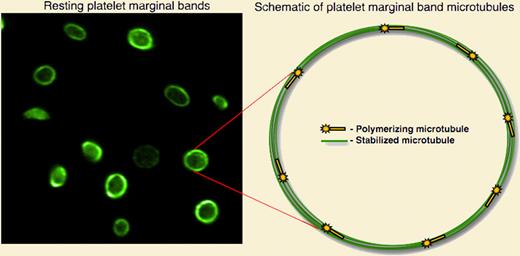

The discoid shape of resting blood platelets is maintained by a marginal band of microtubules, highlighted by staining with antitubulin antibody (left panel). Visualization of cytoskeletal dynamics in live, resting platelets reveals a dynamic marginal band with multiple actively polymerized microtubules.

The discoid shape of resting blood platelets is maintained by a marginal band of microtubules, highlighted by staining with antitubulin antibody (left panel). Visualization of cytoskeletal dynamics in live, resting platelets reveals a dynamic marginal band with multiple actively polymerized microtubules.

Why are the microtubules in the platelet marginal band of microtubules so dynamic? Patel-Hett and colleagues suspect that the marginal band might require constant re-arrangement to facilitate platelet shape changes. Indeed, the study shows that as platelets age, the diameter of the microtubule coil decreases, a phenomenon abolished when microtubule dynamics were blocked with paclitaxel. Thus, dynamic microtubules may accommodate coil shrinkage. Although the majority of this study focuses on microtubule dynamics in resting platelets, it also offers insight into the role of this process in activated platelets. The direct observation of microtubule dynamics in live, activated platelets shows that microtubules polymerize outward and into filopodia as the platelet spreads.

Overall, it is now clear that the platelet marginal band is composed of microtubules that are, in fact, ever-changing dynamic infrastructures of the resting platelet. From a practical standpoint, the current article underscores the limitations of studying platelet biology in fixed cells, particularly as it relates to dynamics of the cytoskeleton. Undoubtedly, the current findings provide the research community with a powerful new methodology for analyzing cellular dynamics in resting and activated platelets and pave the way for advances in the field.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal