Abstract

The decoy receptor D6 plays a nonredundant role in the control of inflammatory processes through scavenging of inflammatory chemokines. However it remains unclear how it is regulated. Here we show that D6 scavenging activity relies on unique trafficking properties. Under resting conditions, D6 constitutively recycled through both a rapid wortmannin (WM)–sensitive and a slower brefeldin A (BFA)–sensitive pathway, maintaining low levels of surface expression that required both Rab4 and Rab11 activities. In contrast to “conventional” chemokine receptors that are down-regulated by cognate ligands, chemokine engagement induced a dose-dependent BFA-sensitive Rab11-dependent D6 re-distribution to the cell membrane and a corresponding increase in chemokine degradation rate. Thus, the energy-expensive constitutive D6 cycling through Rab11 vesicles allows a rapid, ligand concentration–dependent increase of chemokine scavenging activity by receptor redistribution to the plasma membrane. D6 is not regulated at a transcriptional level in a variety of cellular contexts, thus ligand-dependent optimization of its scavenger performance represents a rapid and unique mechanism allowing D6 to control inflammation.

Introduction

Chemokines are a family of small secreted proteins whose main function is leukocyte chemoattraction, exerted through the activation of a family of specific 7 transmembrane domain G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs).1,2 Other than these “conventional” receptors, an emerging subfamily of chemokine receptors with structural homology to signaling receptors that binds the ligand with high affinity but neither mediates cell migration nor activates conventional signaling pathways has been described.3,4 The best-characterized representative of this subfamily is D6, a high-affinity receptor for most inflammatory CC chemokines, including CC chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), CCL3L1, CCL4, CCL5, CCL7, CCL8, CCL11, CCL13, CCL14, CCL17, and CCL22. D6 is expressed in circulating leukocytes at low levels5,6 and at high levels in trophoblasts7 and on endothelial cells of lymphatic afferent vessels in skin, gut, and lung.8 In vitro data indicate a decoy function for D6, which both in lymphatic endothelial cells and in trophoblasts acts as a trap for the ligand and leads to its degradation.7,9,10 When tested in several inflammation models, D6−/− mice consistently displayed an exacerbated inflammatory response, which is accompanied by the development of psoriasiform or granuloma-like lesions in the skin, depending on the different experimental system investigated,11,12 increased inflammation-driven fetal loss rate,7 inflammation-promoted cancer development,13 susceptibility to infectious agents (M.L. and A.M., unpublished data, December 2007), and protection from experimental acute encephalomyelitis due to impaired development of a specific immune response.14 In all models tested, D6−/− mice presented increased local chemokine concentrations and a consequent increase in leukocyte infiltrate, which could be prevented by blocking inflammatory CC chemokines.

After agonist engagement, chemokine receptors associate with β-arrestin and are rapidly internalized mainly via clathrin-coated vesicles.15 Receptors internalized via this pathway are then targeted to early endosomes by a process regulated by the small GTPases dynaminII (Dyn) and Rab516 and can be either delivered to the degradative pathway or recycled to the cell surface via a “rapid” pathway involving Rab4 or a parallel “slow” one involving Rab11-positive recycling endosomes, and possibly the trans Golgi network (TGN).17 Furthermore, some receptors are stored inside the cells in specialized vesicles that can rapidly fuse with the membrane upon stimulation.18 Very little information is available about chemokine receptors' recycling properties. After agonist triggering, CXCR2 and CCR5, the most studied receptors in this context, are recycled through Rab11-recycling endosomes at early time points; while after extended periods of chemokine exposure, they localize to the late endosomal and lysosomal compartments.19-21 Previously published data indicate that D6 is also internalized via the clathrin-mediated pathway in a β-arrestin–dependent way,22 and that D6-mediated chemokine uptake is inhibited by dominant negative forms of Rab5 and Dyn, suggesting that D6 trafficking properties may closely resemble conventional receptors.23 On the other hand, differently from these receptors, in resting conditions D6 is localized mainly in intracellular vesicles,24 it is internalized in a ligand-independent way, and its surface expression is not down-regulated upon chemokine engagement.10,22,23

Given the nonredundant role of D6 in tuning innate immunity and inflammation, comprehension of its regulation by microenvironmental signals is a relevant issue. Here we show that D6 scavenging activity relies on its unique trafficking properties. D6 constitutive cycling occurs through Rab4- and Rab11-dependent pathways and ligand recognition per se rapidly mobilizes the intracellular D6 pool in a Rab11-dependent way, thus up-regulating its membrane expression and optimizing the scavenging properties.

Methods

Chemicals and antibodies

Wortmannin (WM) and cycloheximide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Brefeldin A (BFA) was from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Recombinant human chemokines were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). 125I-CCL4 was from Amersham Biosciences (GE Healthcare Europe, Milan, Italy). Unconjugated and phycoerythrin-conjugated rat anti–human D6 monoclonal antibodies were from R&D Systems. Primary antibodies for early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1) and Rab4 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), Rab11 (Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, CA), syntaxin 6 (Synaptic Systems, Göttingen, Germany), furin convertase (Affinity BioReagents, Golden, CO), vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 (VAMP2; Stressgen, Victoria, BC), insulin-regulated aminopeptidase (IRAP; Alpha Diagnostic International, San Antonio, TX), lysosome-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and the secondary antibodies allophycocyanin-conjugated goat anti–rat IgG (Caltag Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA) and Alexa Fluor647–conjugated goat anti–rabbit IgG and Alexa Fluor594–conjugated goat anti–rat IgG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were used in flow cytometry and immunofluorescence microscopy. Alexa Fluor647–conjugated transferrin (Tf) and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) were purchased from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen).

Cell culture and transfection

CHO-K1 transfectants, HTR8-SV40/D6 cells, and the choriocarcinoma cell line JAR were grown in DMEM/F12 (Cambrex, East Rutherford, NJ) supplemented with 10% FCS (Euroclone, Milan, Italy) and 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin (Cambrex). CHO-K1 transfectants and CCR5-pEGFP and D6-pEGFP plasmids have been previously described.10,22 HTR8-SV40/D6 cells were obtained as previously described.7 pEGFP-N1 was from Clontech Laboratories (Mountain View, CA). Rab5-S34N-pEGFP, Rab4-Q67L-pEGFP, Rab4-S22N-pEGFP, and Rab11-Q70L-pEGFP were generously provided by Robert Lodge (INRS-Institute Armand Frappier and Center for Host Parasite Interactions, Laval, QC). The Rab11-S25N-pEGFP construct was produced as previously described.25 Dyn-K44A-pEGFP was generously provided by Simona Polo (FIRC Institute of Molecular Oncology Foundation [IFOM]-European Institute of Oncology [IEO] Campus, Milan, Italy). CHO-K1 and CHO-K1 cells stably transfected with D6 (CHO-K1/D6) (5 × 107) were transiently transfected with the above-indicated pEGFP-plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and analyzed after 24 hours.

D6 internalization and cell surface expression

Antibody feeding experiments were performed to evaluate D6 internalization. CHO-K1/D6 cells and indicated transfectants (5 × 105) were washed with PBS (Biosera, East Sussex, United Kingdom) supplemented with 1% BSA (GE Healthcare Europe) and stained on ice with 5 μg/mL anti-D6 antibody for 1 hour. Labeled cells were washed and then incubated for the indicated times at 37°C in DMEM-F12 with 1% BSA to allow D6 internalization. Where indicated, CCL3L1 (100 nM), WM (1 μM), and BFA (35 nM) were added. Samples were then returned to ice, washed, and incubated with anti–rat IgG allophycocyanin for 30 minutes in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (PBS supplemented with 1% BSA and 0.01% NaN3). To evaluate D6 up-regulation on cell surface, cells (5 × 105) were incubated at 37°C with the indicated chemokine for different times in DMEM-F12 with 1% BSA. Where indicated, CHO-K1/D6 cells were incubated as follows: 30 minutes with WM (1 μM), BFA (35 nM), and CCL3L1 (100 nM), 2 hours with WM and BFA, and 30 minutes with WM, BFA, and CCL3L1. Cells were then transferred on ice, washed, and labeled with FACS buffer containing 5 μg/mL anti-D6 phycoerythrin-conjugated antibody for 1 hour. For all experiments, 3 × 105 events of viable cells were acquired using a FACS Canto flow cytometer and analyzed using the FACS Diva software (BD Biosciences).

Chemokine scavenging assay

CHO-K1/D6 cells transfected with pEGFP plasmids were sorted using a BD FACS Aria cell sorter (BD Biosciences) and incubated overnight in 96-well plates (5 × 104 cells/well). JAR and HTR8-SV40/D6 cells were plated the day before the experiment in 96-well dishes at the concentration of 3 × 104 cells/well. Cells were then incubated at 37°C for 6 hours in 60 μL DMEM-F12 supplemented with 1% BSA, 0.1 nM 125I-CCL4, and indicated concentrations of unlabeled CCL4. Where indicated, 1 μM WM and 35 nM BFA were added. Proteins in the supernatants were precipitated with 12.5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA; Carlo Erba Reagents, Milan, Italy) at 4°C for 15 minutes, and both soluble and insoluble fractions were counted. Cell-associated fraction was obtained by lysing cells at 4°C for 5 minutes with a buffer containing 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 10 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaN3, 150 mM NaCl, and Triton X-100. The radioactivity present in each fraction was measured using a WIZARD automatic γ counter (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). Degradation rate curves were obtained by data fitting with nonlinear regression and interpolation with Michaelis-Menten equation using the Prism4 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopic analysis

CHO-K1/D6 (105) cells were seeded onto glass dishes in 24-well plates and grown at 37°C for 18 hours. Cells were stimulated with 100 nM CCL3L1 in DMEM-F12 supplemented with 1% BSA in the absence or presence of Alexa Fluor647–conjugated Tf (5 μg/mL), fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 minutes, and incubated with 10% normal goat serum (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) for 30 minutes. Fixed cells were incubated with primary antibodies for 2 hours at room temperature. After washing 3 times with 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS (pH = 7.4), coverslips were incubated with secondary antibodies as indicated in “Chemicals and antibodies” for 1 hour, extensively washed, and incubated with DAPI for 5 minutes. Specimens were mounted in FluoSave (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), and high-resolution images (1024 × 1024 pixels) were acquired sequentially with a 60×/1.4 NA Plan-Apochromat oil-immersion objective using a FV1000 laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany). For z-stack analysis, high-resolution images (1.024 × 1.024 pixels) corresponding to n = 50 optical sections (slice = 100 nm) were sequentially acquired as described in “Chemicals and antibodies.” Differential interference contrast (DIC; Nomarski technique) was also used. Images were assembled and cropped using the Photoshop software (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). Quantitative colocalization and statistical analysis were performed using the ImarisColoc software (version 4.2; Bitplane AG, Zurich, Switzerland). Quantification of D6 colocalization volume (CV) and Pearson coefficient of correlation (PCC) with the indicated markers were performed inside a selected region of interest per image, representative of the analyzed cell.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by unpaired Student t test and, where indicated, with Mann-Whitney test (Prism 4; GraphPad Software).

Results

Ligand stimulation increased D6 scavenging rate and membrane expression

Given the nonredundant role of D6 in tuning the chemokine system and controlling inflammatory reactions, we expected this decoy receptor to be strictly regulated. However, in a variety of cellular contexts, including monocytes, neutrophils, and trophoblast cells, we consistently failed to observe changes in D6 transcript levels in response to inflammatory and anti-inflammatory signals (E.M.B. and R.B., unpublished data, October 2007). We therefore focused our attention on the unique trafficking properties of this molecule.23 Acute exposure of chemokine receptors to their ligands results in rapid internalization of both molecules, ligand degradation, and receptor recycling on the membrane. In case of continuous exposure to the ligand, this mechanism contributes to receptor down-regulation and to switching off the biologic response.15,26,27 Differently from chemotactic receptors, flow cytometry analysis on CHO-K1/D6 cells demonstrated that the membrane expression levels of the chemokine scavenger receptor D6 were significantly up-regulated in response to all D6 ligands tested, whereas chemokines not recognized by D6, such as CCL3, CCL19, and CXC chemokine ligand 8 (CXCL8), were inactive (Figure 1A). This effect was concentration dependent, being detectable from 30 nM and reaching a plateau at 100 nM (Figure 1B), and time dependent, starting 10 minutes after stimulation, reaching a maximum after 1 hour, and decreasing thereafter (Figure 1C). D6 up-regulation after chemokine addition was also observed in the trophoblast cell line HTR8-SV40/D6 (123.77% ± 4.55%, n = 5, P < .01 after 60 minutes of 100 nM CCL3L1). Analysis of D6 expression levels by confocal microscopy revealed that under resting conditions most of the receptor was stored in perinuclear compartments, whereas ligand engagement induced relocation of a significant fraction of the receptor to the cell membrane (Figure 5). To investigate the effect of this up-regulation on the ability to mediate ligand degradation, CHO-K1 transfectants expressing comparable levels of the conventional chemokine receptor CCR5 or the chemokine scavenger receptor D6 were incubated with increasing concentrations of the shared ligand CCL4 and ligand degradation rate was analyzed. CCR5-mediated ligand degradation reached a plateau at 30 nM, with a maximal rate of 3.3 × 10−9 plus or minus 8.39 × 10−10 nmol/s, whereas D6-mediated scavenging rate increased as a function of ligand concentration reaching a rate of 2.3 × 10−8 plus or minus 4.04 × 10−9 nmol/s at 300 nM (Figure 1D). Similar results were obtained using the choriocarcinoma cell line JAR that endogenously expresses D6 (scavenging rate of 3.27 × 10−8 ± 8.03 × 10−9 nmol/s at 300 nM CCL3L1; Figure 1D) and the trophoblast cell line HTR8-SV40/D6 (scavenging rate of 1.29 × 10−7 ± 1.78 × 10−8 nmol/s at 300 nM CCL3L1). These results indicate that chemokines induce a significant up-regulation of D6 expression on the membrane, thus improving its scavenging performance.

D6 increased its membrane expression and scavenging rate upon ligand stimulation. (A-C) CHO-K1/D6 cells were incubated at 37°C with (A) 100 nM of the indicated chemokine for 30 minutes, (B) increasing concentrations of CCL3L1 for 60 minutes, (C) medium (□) or 100 nM CCL3L1 (■) for the indicated times. D6 membrane expression was analyzed by flow cytometry and data were expressed as percentage of MFI over untreated cells. Results (means ± SEM) were from at least 3 independent experiments performed. Asterisks indicate significant differences of cells incubated with indicated chemokine versus untreated cells (*P < .05; **P < .01). (D) JAR (●) and CHO-K1 cells transiently transfected with CCR5-pEGFP (□) or D6-pEGFP (■) were sorted and then incubated at 37°C with 0.1 nM 125I-CCL4 and 1 to 300 nM CCL4. Data were analyzed as described in “Chemokine scavenging assay.” Results (means ± SEM) shown in panels A-C are from at least 3 different experiments performed, and asterisks indicate significant differences between medium and treated cells; results (means ± SEM) in panel D are from triplicates of 1 representative experiment of 3 performed. Asterisks indicate significant differences between JAR- and CHO-K1/D6- versus CHO-K1/CCR5-transfected cells (*P < .05; **P < .01).

D6 increased its membrane expression and scavenging rate upon ligand stimulation. (A-C) CHO-K1/D6 cells were incubated at 37°C with (A) 100 nM of the indicated chemokine for 30 minutes, (B) increasing concentrations of CCL3L1 for 60 minutes, (C) medium (□) or 100 nM CCL3L1 (■) for the indicated times. D6 membrane expression was analyzed by flow cytometry and data were expressed as percentage of MFI over untreated cells. Results (means ± SEM) were from at least 3 independent experiments performed. Asterisks indicate significant differences of cells incubated with indicated chemokine versus untreated cells (*P < .05; **P < .01). (D) JAR (●) and CHO-K1 cells transiently transfected with CCR5-pEGFP (□) or D6-pEGFP (■) were sorted and then incubated at 37°C with 0.1 nM 125I-CCL4 and 1 to 300 nM CCL4. Data were analyzed as described in “Chemokine scavenging assay.” Results (means ± SEM) shown in panels A-C are from at least 3 different experiments performed, and asterisks indicate significant differences between medium and treated cells; results (means ± SEM) in panel D are from triplicates of 1 representative experiment of 3 performed. Asterisks indicate significant differences between JAR- and CHO-K1/D6- versus CHO-K1/CCR5-transfected cells (*P < .05; **P < .01).

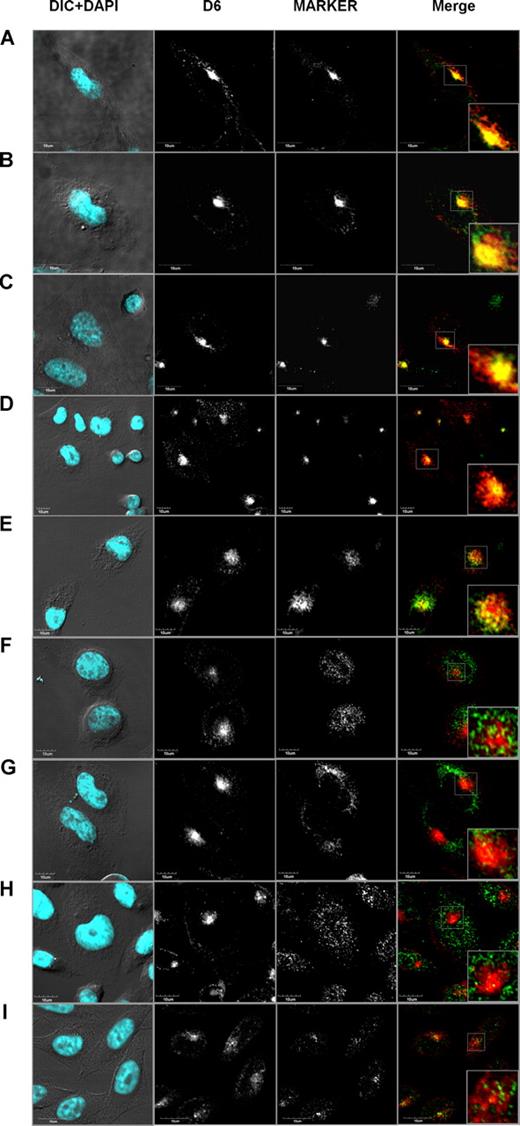

D6 colocalized with markers of rapid and slow recycling pathways

Various mechanisms could be responsible for ligand-induced increased expression of D6. Antibody feeding experiments have demonstrated that chemokines do not modify D6 internalization rate,22 and continuous treatment with cycloheximide had no effect on D6 expression levels and on its redistribution after ligand addition, suggesting that neosynthesis has no major role (data not shown). This implies that chemokines might increase receptor recycling rate or mobilize intracellular D6 stores. To identify the intracellular compartments in which D6 constitutively cycles, confocal microscopy analysis in CHO-K1/D6 cells was performed. D6 showed a strong colocalization with the early endosomes marker EEA1 (Figure 2A; CV: 68.79% ± 1.43%, PCC = 0.743 ± 0.008, n = 82). D6 was also colocalized with Rab4 (Figure 2B; CV: 84.74% ± 0.98%, PCC = 0.755 ± 0.01, n = 64), the recycling endosomes marker Rab11 (Figure 2C; CV: 75.37% ± 1.68%, PCC = 0.807 ± 0.08, n = 30), and labeled Tf (Figure 2D; CV: 76.38% ± 0.83%, PCC = 0.782 ± 0.04, n = 170). On the contrary, a minority of D6 was found colocalized with the early endosomes and TGN marker syntaxin 6 (Figure 2E; CV: 35.7% ± 2.93%, PCC = 0.793% ± 0.05%, n = 34), and no colocalization was observed with the late endosomes and TGN marker furin (Figure 2F), the 2 markers of insulin-specific vesicles VAMP2 and IRAP (Figure 2G,H, respectively) and the late endosome/lysosome marker LAMP1 (Figure 2I). Taken together, these results indicate that under basal conditions D6 is present in early endosome vesicles (EEA1, and syntaxin 6 positive) and in recycling vesicles (Rab4, Rab11, and Tf positive), and does not traffic in lysosomes, TGN, or insulin-specific vesicles.

D6 colocalized with markers of rapid and slow recycling pathways. Confocal images of immunofluorescence-stained CHO-K1/D6 cells. Panels show representative experiments of D6 staining with vesicle markers EEA1 (A), Rab4 (B), Rab11 (C), Tf (D), syntaxin 6 (E), furin (F), VAMP2 (G), IRAP (H), and LAMP1 (I). In the first column, the nuclear staining (DAPI, light blue) is merged to the DIC image; D6 and vesicle marker expression alone are shown in second and third column, respectively. The fourth column represents the double staining of D6 (red) and vesicle markers (green). Inserts represent magnifications of the boxed area in the double-staining images.

D6 colocalized with markers of rapid and slow recycling pathways. Confocal images of immunofluorescence-stained CHO-K1/D6 cells. Panels show representative experiments of D6 staining with vesicle markers EEA1 (A), Rab4 (B), Rab11 (C), Tf (D), syntaxin 6 (E), furin (F), VAMP2 (G), IRAP (H), and LAMP1 (I). In the first column, the nuclear staining (DAPI, light blue) is merged to the DIC image; D6 and vesicle marker expression alone are shown in second and third column, respectively. The fourth column represents the double staining of D6 (red) and vesicle markers (green). Inserts represent magnifications of the boxed area in the double-staining images.

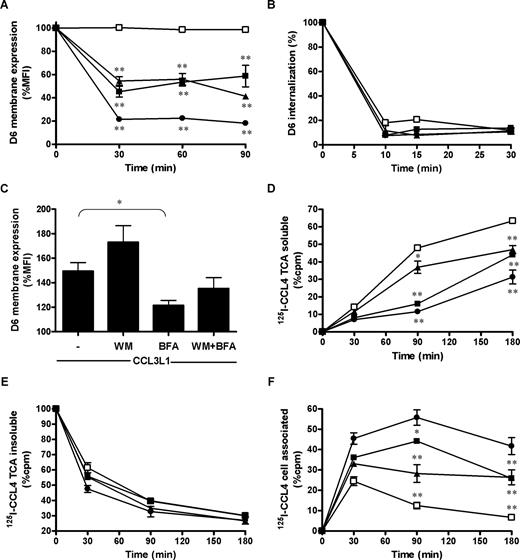

D6 recycling and function were impaired by BFA and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitors

The strong association of D6 with Rab4, Rab11, and Tf suggests that receptor cycling might occur via different pathways. Internalized membrane molecules can exit from early endosomes directly to the plasma membrane via a direct rapid recycling pathway or a slower recycling pathway that involves transit in the recycling endosomes before the return to the plasma membrane. The distinct nature of these recycling pathways is reflected by their differential sensitivity to pharmacologic tools, including the phosphatidylinositol kinase (PI3K) inhibitors and BFA,28 as previously described for the transferrin receptor (TfR),29 the angiotensin receptor 1,30 and the neurotensin receptor 2.31 Moreover, specific small GTPases of the Rab family have been implicated in the control of recycling pathways,15,17 with Rab4 located in early sorting endosomes and regulating the direct recycling of receptors back to the plasma membrane and Rab11 involved in passage of the recycling receptors through recycling endosomal compartment.32

Flow cytometric analysis revealed approximately 50% reduction of D6 surface expression levels, in resting conditions, after 30-minute treatment of CHO-K1/D6 transfectants with the PI3K inhibitors WM (EC50 = 100 nM; Figure 3A) and LY294002 (EC50 = 300 nM; data not shown), demonstrating that PI3K activity is required to maintain the cell surface level of D6. A similar inhibitory effect was obtained with BFA (EC50 = 35 nM; Figure 3A), and an additive effect was observed when PI3K inhibitors and BFA were used in combination (Figure 3A, and data not shown). Similar results were obtained with HTR8-SV40/D6 transfectants (1 μM WM: 69.20% ± 4.10%, n = 5, P < .01; 35 nM BFA: 69.37% ± 6.6% of D6 basal expression, n = 5, P < .01; WM + BFA: 49.93% ± 4.55% of D6 basal expression, n = 5, P < .05 vs WT or BFA alone). D6 internalization was studied by antibody feeding experiments using anti-D6 antibody at 4°C to label only D6 membrane pool. Washed cells were then returned to 37°C with or without the chemokine for different times as described in “D6 internalization and cell surface expression.” Cell treatment with WM, BFA, or both drugs did not modify D6 internalization rate (Figure 3B). Conversely, ligand-induced up-regulation was slightly potentiated by WM treatment, and was significantly reduced by BFA treatment (Figure 3C). Consistently with previously published data,33,34 in CHO-K1/CCR5 transfectants WM and BFA had no effect on CCR5 basal expression, internalization, and recycling (data not shown). These results suggest that in basal conditions D6 cycles through 2 distinct recycling pathways, selectively inhibited by WM and BFA, similarly to the TfR CD71.29 On the contrary, receptor up-regulation consequent to ligand engagement is accounted for mainly by the BFA-sensitive pathway.

D6 recycling and function were impaired by WM and BFA. (A,B) CHO-K1/D6 cells were incubated at 37°C for the indicated times with medium (□), 1 μM WM (■), 35 nM BFA (▲), or both inhibitors (●), and analyzed for D6 membrane expression (A) or D6 internalization (B). (C) CHO-K1/D6 cells were incubated with 100 nM CCL3L1 for 1 hour with the indicated inhibitors, and D6 up-regulation on cell surface was evaluated as described in “D6 internalization and cell surface expression.” Data are percentages of MFI of each cell treatment over basal conditions; asterisks indicate significant differences of cells incubated with indicated inhibitor versus untreated cells calculated with Student t test and Mann-Whitney test. (D-F) CHO-K1/D6 cells were incubated at 37°C with 0.4 nM CCL4 mixed with 0.1 nM 125I-CCL4 in the presence of indicated inhibitors. Data are the percentage of radioactivity counted (cpm) over CHO-K1 cells in the TCA-soluble (D) and TCA-insoluble (E) fractions of the supernatants and in the cell-associated fractions (F). Results shown in panels A-C (means ± SEM) are from at least 3 independent experiments performed; results of panels D through F (means ± SEM) are from triplicates of 1 representative experiment of 3 performed. Asterisks indicate significant differences of cells incubated with indicated inhibitor versus untreated cells (*P < .05; **P < .01).

D6 recycling and function were impaired by WM and BFA. (A,B) CHO-K1/D6 cells were incubated at 37°C for the indicated times with medium (□), 1 μM WM (■), 35 nM BFA (▲), or both inhibitors (●), and analyzed for D6 membrane expression (A) or D6 internalization (B). (C) CHO-K1/D6 cells were incubated with 100 nM CCL3L1 for 1 hour with the indicated inhibitors, and D6 up-regulation on cell surface was evaluated as described in “D6 internalization and cell surface expression.” Data are percentages of MFI of each cell treatment over basal conditions; asterisks indicate significant differences of cells incubated with indicated inhibitor versus untreated cells calculated with Student t test and Mann-Whitney test. (D-F) CHO-K1/D6 cells were incubated at 37°C with 0.4 nM CCL4 mixed with 0.1 nM 125I-CCL4 in the presence of indicated inhibitors. Data are the percentage of radioactivity counted (cpm) over CHO-K1 cells in the TCA-soluble (D) and TCA-insoluble (E) fractions of the supernatants and in the cell-associated fractions (F). Results shown in panels A-C (means ± SEM) are from at least 3 independent experiments performed; results of panels D through F (means ± SEM) are from triplicates of 1 representative experiment of 3 performed. Asterisks indicate significant differences of cells incubated with indicated inhibitor versus untreated cells (*P < .05; **P < .01).

To evaluate the functional relevance of WM and BFA effect on D6 membrane expression, scavenging assays were performed by incubating CHO-K1/D6 transfectants with 125I-CCL4 for increasing time in the presence or absence of WM, BFA, or both inhibitors. Consistently with results on receptor cycling, each inhibitor exerted a significant effect on D6-mediated chemokine degradation, with WM more effective than BFA at short time point (90 minutes) and a comparable effect of WM and BFA at longer time point (180 minutes). An additive effect of the combined treatment was observed at all time points examined (Figure 3D). Interestingly, the amount of intact chemokine present in the supernatant decreased with a similar rate in control and treated cells (Figure 3E), whereas there was an increased accumulation of 125I-CCL4 inside the cells treated with WM, BFA, or both inhibitors (Figure 3F). Similar effects on CCL3L1 scavenging have been observed with JAR cells (1 μM WM: 44.33% ± 0.47% inhibition, n = 5, P < .01; 35 nM BFA: 33.98% ± 0.80% inhibition, n = 5, P < .01; WM + BFA: 62.60% ± 0.46% inhibition, n = 5, P < .05 vs WT or BFA alone). These results suggest that WM and BFA do not affect chemokine uptake, consistently with the lack of inhibitory effect on D6 internalization (Figure 3B), and that efficient cycling of D6 through both rapid and slow recycling pathways is necessary for chemokine scavenging.

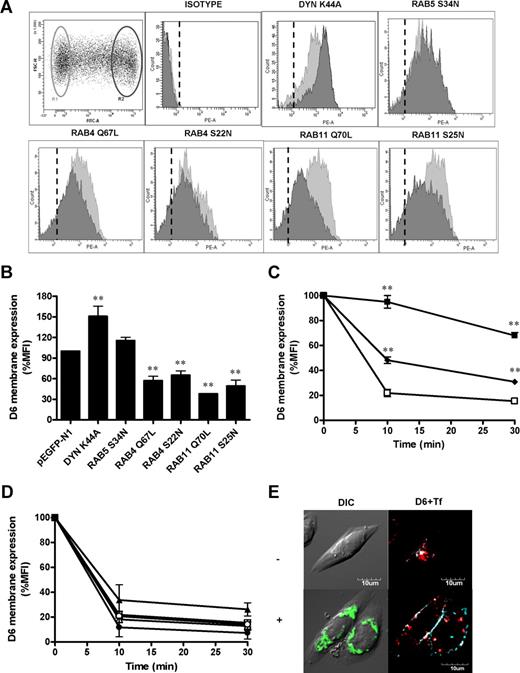

Role of Dyn and Rab proteins in D6 constitutive internalization

To better characterize the molecular mechanisms associated with D6 cycling, GFP-tagged protein mutants involved in endocytic membrane traffic were transiently transfected in CHO-K1/D6 cells. Flow cytometric analysis of D6 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) on gated cells (not transfected and transfected by the various mutants; R1 and R2 gates in Figure 4A, respectively) allowed us to assess the impact of the transfected proteins on D6 internalization and membrane expression. Consistently with previous reports showing that D6 internalization is mediated by clathrin-coated pits,22 CHO-K1/D6 cells transfected with a Dyn dominant negative mutant (Dyn-K44A) which blocks clathrin-coated vesicles pinching from the plasma membrane,35 strongly inhibited D6 constitutive internalization (Figure 4C), resulting in increased cell surface expression of the receptor (Figure 4A,B). Inhibition of D6 internalization by Dyn-K44A was further confirmed by confocal microscopic analysis (Figure 4E). CHO-K1/D6 cells transfected with pEGFP/Dyn-K44A showed increased D6 membrane expression accumulated in late invaginated coated pits, still opened and attached to the plasma membrane and a concomitant decrease of intracellular receptors. Similarly, CHO-K1/D6 cells transfected with the dominant negative mutant of the small GTPase Rab5 (Rab5-S34N), a key regulator of early endocytic traffic,36 showed a decreased spontaneous D6 internalization (Figure 4C), accompanied by a small although not significant increase in membrane expression (Figure 4A,B). Both constitutively active or inactive forms of both Rab4 (Rab4-Q67L and Rab4-S22N, respectively), a regulator of rapid recycling,37 and Rab11 (Rab11-Q70L and Rab11-S25N, respectively), which is involved in slow recycling,38 reduced D6 cell surface expression (Figure 4A,B), but had no effect on D6 constitutive endocytosis (Figure 4D). These results demonstrate that constitutive internalization of D6 is Dyn and Rab5 dependent, whereas Rab4 and Rab11 have a direct role in maintaining D6 membrane expression by recycling the internalized receptor to the plasma membrane.

Role of Dyn and Rab proteins in D6 surface expression and constitutive internalization. (A) Representative FACS analysis of CHO-K1/D6 cells transiently transfected with constructs expressing the indicated pEGFP-tagged proteins. R1 and R2 gates refer to the viable pEGFPneg and pEGFPhigh cells, respectively, in which D6 expression was evaluated. Histograms represent flow cytometric profiles of D6 expression in gated cell population (light gray = R1 gate; dark gray = R2 gate). Dashed lines indicate isotype-matched control mAb. (B) Quantification of D6 membrane expression. Data were expressed as percentage of MFI of R2 over R1 gated population. (C,D) D6 internalization of the indicated CHO-K1/D6 pEGFP-tagged transfectants (□ indicates pEGFP-N1 cells; ■, Dyn-K44A; ♦, Rab5-S34N; ○, Rab4-Q67L; ●, Rab4-S22N; △, Rab11-Q70L; and ▲, Rab11-S25N). Results are means plus or minus SEM from at least 3 independent experiments performed. Asterisks indicate significant differences of Dyn/Rab-transfected versus pEGFP-N1–transfected cells (*P < .05; **P < .01). (E) Confocal images of CHO-K1/D6 cells transiently transfected with pEGFP/Dyn-K44A (green) treated for 30 minutes with Alexa Fluor647–conjugated Tf (light blue) and immunofluorescence stained for D6 (red). Top panel (−): untransfected cells; bottom panel (+): pEGFP/Dyn-K44A–transfected cells.

Role of Dyn and Rab proteins in D6 surface expression and constitutive internalization. (A) Representative FACS analysis of CHO-K1/D6 cells transiently transfected with constructs expressing the indicated pEGFP-tagged proteins. R1 and R2 gates refer to the viable pEGFPneg and pEGFPhigh cells, respectively, in which D6 expression was evaluated. Histograms represent flow cytometric profiles of D6 expression in gated cell population (light gray = R1 gate; dark gray = R2 gate). Dashed lines indicate isotype-matched control mAb. (B) Quantification of D6 membrane expression. Data were expressed as percentage of MFI of R2 over R1 gated population. (C,D) D6 internalization of the indicated CHO-K1/D6 pEGFP-tagged transfectants (□ indicates pEGFP-N1 cells; ■, Dyn-K44A; ♦, Rab5-S34N; ○, Rab4-Q67L; ●, Rab4-S22N; △, Rab11-Q70L; and ▲, Rab11-S25N). Results are means plus or minus SEM from at least 3 independent experiments performed. Asterisks indicate significant differences of Dyn/Rab-transfected versus pEGFP-N1–transfected cells (*P < .05; **P < .01). (E) Confocal images of CHO-K1/D6 cells transiently transfected with pEGFP/Dyn-K44A (green) treated for 30 minutes with Alexa Fluor647–conjugated Tf (light blue) and immunofluorescence stained for D6 (red). Top panel (−): untransfected cells; bottom panel (+): pEGFP/Dyn-K44A–transfected cells.

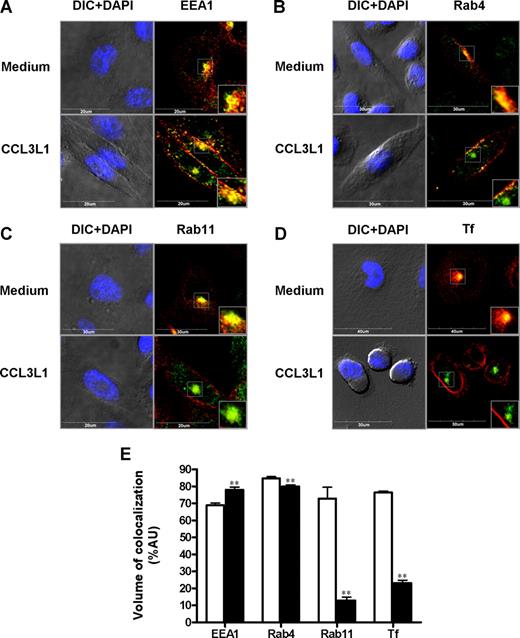

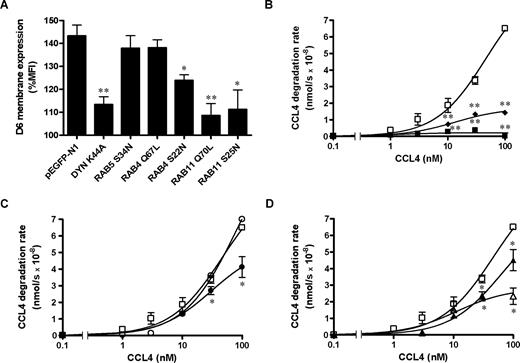

Role of Dyn and Rab proteins on chemokine-induced D6 up-regulation on cell membrane

The molecular basis of D6 intracellular trafficking after chemokine engagement was investigated in CHO-K1/D6 cells labeled with endosomal markers and analyzed by confocal microscopy. After CCL3L1 exposure, D6-increased membrane expression resulted in a marked decrease in colocalization volume with the recycling endosome markers Rab11 (Figure 5C,E) and exogenously added Tf (Figure 5D,E), and a less marked decrease in colocalization volume with Rab4 (Figure 5B,E). On the contrary, D6 colocalization with the early endosomes marker EEA1 was slightly increased (Figure 5A,E). The same pattern of modifications of D6 colocalization with endosomal markers after chemokine addition was confirmed by Z-stack analysis (Figures S1–S3, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). No colocalization of D6 with the lysosome marker LAMP1 was detectable (data not shown), suggesting that after chemokine engagement D6 did not enter the degradative pathway. Overexpression of Dyn-K44A and both dominant negative or constitutively active Rab11 mutants inhibited chemokine-induced D6 up-regulation (Figure 6A). In contrast, chemokine-induced D6 up-regulation was not inhibited by coexpression of the Rab5-S34N dominant negative and Rab4-Q67L constitutively active mutants, and only partially inhibited by the Rab4-S22N dominant negative mutant (Figure 6A). Finally, to test the functional relevance of D6 cycling and chemokine-induced up-regulation, scavenging assays were performed in CHO-K1/D6 cells transiently transfected with dominant negative and constitutively active EGFP-tagged GTPases. As expected, CCL4 scavenging was inhibited by Rab5-S34N and Dyn-K44A overexpression (Figure 6B), whereas overexpression of the constitutively active Rab4-Q67L mutant had no effect (Figure 6C). Consistently with the chemokine-dependent D6 membrane up-regulation data, dominant negative Rab4-S22N and Rab11-S25N and constitutively active Rab11-Q70L mutants significantly affected chemokine scavenging at high concentrations (Figure 6C,D), with a stronger effect obtained with the constitutively active form of Rab11 (Rab11-Q70L; Figure 6D). These data suggest that internalization and recycling of D6 is necessary for its chemokine-dependent up-regulation and subsequent increase in scavenging efficiency.

Chemokine stimulation decreased D6 colocalization with Rab proteins. Confocal analysis of CHO-K1/D6 cells stained for D6 expression with EEA1 (A), Rab4 (B), Rab11 (C), and Tf (D) in presence or absence of CCL3L1 (100 nM, 30 minutes). For each panel, the first column represents nuclear staining (DAPI, light blue) merged to the DIC image, and the second column shows D6 (red) and Rabs/Tf (green) expression. Inserts show magnifications of the boxed area. (E) Quantification of D6 colocalization volume with the indicated endosomal marker in basal conditions (□) and after CCL3L1 addition (100 nM, 30 minutes; ■). Results are means plus or minus SEM from the analysis of at least 30 different images, obtained in 3 independent experiments, performed as described in “Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopic analysis.” Asterisks indicate significant differences between cells incubated with CCL3L1 and untreated cells (*P < .05; **P < .01).

Chemokine stimulation decreased D6 colocalization with Rab proteins. Confocal analysis of CHO-K1/D6 cells stained for D6 expression with EEA1 (A), Rab4 (B), Rab11 (C), and Tf (D) in presence or absence of CCL3L1 (100 nM, 30 minutes). For each panel, the first column represents nuclear staining (DAPI, light blue) merged to the DIC image, and the second column shows D6 (red) and Rabs/Tf (green) expression. Inserts show magnifications of the boxed area. (E) Quantification of D6 colocalization volume with the indicated endosomal marker in basal conditions (□) and after CCL3L1 addition (100 nM, 30 minutes; ■). Results are means plus or minus SEM from the analysis of at least 30 different images, obtained in 3 independent experiments, performed as described in “Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopic analysis.” Asterisks indicate significant differences between cells incubated with CCL3L1 and untreated cells (*P < .05; **P < .01).

Role of Dyn and Rab proteins on chemokine-induced D6 up-regulation on cell membrane and scavenging activity. CHO-K1/D6 cells were transiently transfected with the indicated pEGFP-tagged constructs. (A) Quantification of D6 membrane expression expressed as percentage of MFI of each transfected cell population treated with CCL3L1 (100 nM, 30 minutes) over untreated controls. Results (means ± SEM) are from at least 3 independent experiments. CCL4 degradation rate of sorted transfectants is shown in panels B (□ indicates pEGFP-N1; ■, Dyn-K44A; and ♦, Rab5-S34N), C (□ indicates pEGFP-N1; ○, Rab4-Q67L; and ●, Rab4-S22N), and D (□ indicates pEGFP-N1; △, Rab11-Q70L; and ▲, Rab11-S25N). Data were analyzed as described in “Chemokine scavenging assay.” Results (means ± SEM) shown in panel A are from at least 3 different experiments; results in panels B through D are from triplicates of 1 representative experiment of at least 3 performed. Asterisks indicate significant differences of Dyn/Rab-transfected versus pEGFP-N1–transfected cells (*P < .05; **P < .01).

Role of Dyn and Rab proteins on chemokine-induced D6 up-regulation on cell membrane and scavenging activity. CHO-K1/D6 cells were transiently transfected with the indicated pEGFP-tagged constructs. (A) Quantification of D6 membrane expression expressed as percentage of MFI of each transfected cell population treated with CCL3L1 (100 nM, 30 minutes) over untreated controls. Results (means ± SEM) are from at least 3 independent experiments. CCL4 degradation rate of sorted transfectants is shown in panels B (□ indicates pEGFP-N1; ■, Dyn-K44A; and ♦, Rab5-S34N), C (□ indicates pEGFP-N1; ○, Rab4-Q67L; and ●, Rab4-S22N), and D (□ indicates pEGFP-N1; △, Rab11-Q70L; and ▲, Rab11-S25N). Data were analyzed as described in “Chemokine scavenging assay.” Results (means ± SEM) shown in panel A are from at least 3 different experiments; results in panels B through D are from triplicates of 1 representative experiment of at least 3 performed. Asterisks indicate significant differences of Dyn/Rab-transfected versus pEGFP-N1–transfected cells (*P < .05; **P < .01).

Discussion

Chemokine decoy receptors have recently been demonstrated to play a nonredundant role in controlling inflammation in several animal models.4 The best-described chemokine decoy receptor, the D6 molecule, has been shown to act as a gatekeeper, controlling leukocyte recruitment in inflamed tissues and preventing excessive accumulation of inflammatory chemokines in draining lymph nodes.39 Several features distinguish conventional chemokine receptors from D6, which appears to be structurally adapted to perform chemokine scavenging being constitutively internalized and not down-regulated after chemokine engagement.9,22,23 Data presented in this study demonstrate that D6 internalizes and degrades inflammatory chemokines more efficiently than conventional chemokine receptors due to its unique cycling proprieties.

Prolonged exposure to the ligand typically results in chemokine receptor down-regulation due to receptor internalization and degradation.19 On the contrary, both on cell transfectants and on choriocarcinoma cell lines endogenously expressing D6, cells exposed to increasing chemokine concentrations display increased scavenging rate, suggesting that the receptor is not down-regulated. Indeed, the receptor levels are actually up-regulated when high ligand concentrations are present in the extracellular milieu. Results presented here indicate that this increased scavenging activity is not due to modifications in receptor internalization rate, but to a dose-dependent receptor up-regulation on cell membrane due to translocation of intracellular D6 present in recycling vesicles. Consistent with previous reports,24 confocal microscopic analysis shows that in basal conditions D6 exists predominantly in endosomal compartments, although it is barely detectable on cell surface. Here we also report that D6 is present in early and recycling endosomes colocalized with EEA1, Rab4, and Rab11, although it is not detectable in lysosomes, TGN, and insulin-sensitive vesicles. After chemokine addition, D6 colocalization with recycling endosome markers decreases and membrane staining increases, suggesting that chemokines induce mobilization of D6 from recycling compartments.

Using a pharmacologic approach, we identified 2 pathways involved in D6 recycling: a rapid PI3K-dependent pathway involved mainly in maintaining D6 expression in steady state, and a slower BFA-sensible pathway that accounts for both D6 basal membrane expression and chemokine-induced receptor up-regulation. Both WM and BFA pretreatment inhibit chemokine scavenging, with WM more effective at early time points whereas BFA inhibition is evident only 30 minutes after chemokine addiction. These results were strengthened by a genetic approach based on the expression of dominant negative and constitutively active mutants of small GTPases involved in internalization and recycling trafficking. Overexpression of the dominant negative mutants of Dyn (Dyn-K44A) and Rab5 (Rab5-S34N), regulators of vesicles endocytosis, inhibits D6 internalization rate and D6-mediated chemokine degradation, in agreement with previously published results.23 Differently from Rab5-S34N, Dyn-K44A overexpression also results in increased D6 membrane expression in steady-state conditions and inhibition of chemokine-induced D6 up-regulation. By inhibiting budding of clathrin-coated vesicles either from plasma membrane or from recycling vesicles,29 Dyn-K44A overexpression completely blocks receptor function, most likely preventing the formation of D6 intracellular stores necessary for chemokine-induced receptor up-regulation. Genetic interference of both Rab4 and Rab11 determines a reduction of D6 membrane expression without affecting receptor internalization rate, suggesting that the activity of these small GTPases is required for D6 recycling to maintain D6 expression on cell surface. Interestingly, comparable inhibition is obtained by overexpression of dominant negative and constitutively active forms of both Rab4 and Rab11, similarly to what was previously reported for TfR,40 E-cadherin,41 and the cAMP-activated chloride channel CFTR.42 On the contrary, chemokine-induced D6 up-regulation displays differential inhibition by Rab4 and Rab11 mutants. The up-regulation is not affected by overexpression of constitutively active Rab4 mutant, it is partially inhibited by Rab4 and Rab11 dominant negative mutants, and it is strongly affected by constitutively active Rab11 (Rab11-Q70L). The inhibition of D6 up-regulation is paralleled by decreased chemokine degradation rate at high chemokine concentrations. These data are in agreement with previous results describing a central role for Rab11 not only for entrance of molecules into the recycling compartment but also for direct recycling from the sorting endosome to the cell surface.40 The active form of Rab11, associating with the motor protein myosin Vb,43 is required for the transfer of receptors from sorting endosomes to the recycling compartment, whereas the constitutively active form of Rab11 (Rab11-Q70L) acts by inhibiting the exit of receptors from this compartment, as this step requires dissociation from microtubules and hydrolysis of GTP, as demonstrated for the M4-muscarininc receptor trafficking44 and CXCR2 trafficking.21 These data indicate that D6 not only is sorted in the early endosome to the plasma membrane, but also transits through the recycling endosome, a process that is regulated by Rab11. Studies on other GPCRs suggest that their accumulation in the recycling endosome is dependent upon the phosphorylation status of serine/threonine residues in the cytoplasmic tail of the receptor or its association with β-arrestin.45,46 Although the precise molecular mechanisms involved in D6 sorting to the different pathways are presently unknown, data presented here clearly show that Rab11 activity is necessary for the correct transit of D6 through recycling endosomes and for rapid receptor mobilization upon chemokine stimulation, and ultimately for efficient chemokine degradation in a wide range of concentrations.

Constitutive cycling of certain enzymatic pathways is referred to as “futile cycle” because it is an energy-expensive process without energy gain. It has been proposed that this energetic cost is necessary for extremely sensitive systems because small changes in the rate of one of these reactions provides a mean to rapid changes in net flux without need for protein synthesis.47 Constitutive cycling has also been demonstrated for several transmembrane proteins, such as receptors at the mammalian synapse,48 adhesion molecules, ion channels, and transporters.18,49 Exocytic and endocytic trafficking at the cell surface of these molecules can be exquisitely regulated both in time and in space, thus tightly coping with changes in cellular requirements.49 Interestingly, the macrophage scavenger receptor for modified lipoproteins stabilin-150 and the macrophage scavenger receptor for hemoglobin CD16351 also undergo a constitutive internalization and recycling process that is significantly increased in response to ligand binding. Similarly, here we report that the constitutive cycling decoy receptor for inflammatory chemokine D6 displays enhanced scavenging activity after ligand engagement. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that constitutive cycling and ligand-dependent receptor up-regulation might represent mechanisms used by scavenger receptors, including chemokine decoy receptors, to rapidly modulate ligand uptake and degradation depending on the immediate needs of the tissue. D6 is not regulated at a transcriptional level in a variety of cellular contexts, thus ligand concentration–dependent optimization of its scavenger performance represents a rapid and unique mechanism allowing D6 to control inflammation.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Simona Polo (FIRC Institute of Molecular Oncology Foundation [IFOM]–European Institute of Oncology [IEO] Campus, Milan, Italy) and Robert Lodge (Institut national de la recherche scientifique [INRS]–Institute Armand Frappier and Center for Host Parasite Interactions, Laval, QC) for expression vectors used in this study, and Chiara Buracchi (Istituto Clinico Humanitas, Milan, Italy) for excellent graphic support.

This study was supported by research grants of the European Community (Brussels, Belgium; INNOCHEM project 518167; EMBIC project 512040), the Ministero dell'Istruzione dell'Università e della Ricerca (Rome, Italy; PRIN project 2002061255; FIRB project RBIN04EKCX), and Fondazione Cariplo (Milan, Italy; NOBEL project). This work was conducted in the context and with the support of the Fondazione Humanitas per la Ricerca (Rozzano, Milan, Italy). The generous contribution of the Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC, Milan, Italy) is gratefully acknowledged.

Authorship

Contribution: R.B. designed the research, analyzed results, and wrote the paper; E.M.B. performed experiments, analyzed results, and made the figures; A.A., A.D., B.S., and M.M. performed experiments; M.F., V.R.J., and B.H. contributed vital new reagents; A.M. and M.L. designed the research and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Raffaella Bonecchi, Istituto Clinico Humanitas IRCCS, Via Manzoni 56, I-20089 Rozzano, Italy; e-mail: raffaella.bonecchi@humanitas.it.

References

Author notes

*R.B. and E.M.B. contributed equally to this work.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal