Abstract

Subjects with X-linked hyper-IgM syndrome (X-HIgM) have a markedly reduced frequency of CD27+ memory B cells, and their Ig genes have a low level of somatic hypermutation (SHM). To analyze the nature of SHM in X-HIgM, we sequenced 209 nonproductive and 926 productive Ig heavy chain genes. In nonproductive rearrangements that were not subjected to selection, as well as productive rearrangements, most of the mutations were within targeted RGYW, WRCY, WA, or TW motifs (R = purine, Y = pyrimidine, and W = A or T). However, there was significantly decreased targeting of the hypermutable G in RGYW motifs. Moreover, the ratio of transitions to transversions was markedly increased compared with normal. Microarray analysis documented that specific genes involved in SHM, including activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AICDA) and uracil-DNA glycosylase (UNG2), were up-regulated in normal germinal center (GC) B cells, but not induced by CD40 ligation. Similar results were obtained from light chain rearrangements. These results indicate that in the absence of CD40-CD154 interactions, there is a marked reduction in SHM and, specifically, mutations of AICDA-targeted G residues in RGYW motifs along with a decrease in transversions normally related to UNG2 activity.

Introduction

Encounter with antigen and CD40-CD154 costimulation activates naive B cells to undergo a germinal center (GC) reaction1,2 during which somatic hypermutation (SHM) introduces point mutations in the Ig variable segment involved in antigen recognition and, thus, is an important mechanism for increasing avidity maturation and repertoire diversity.3 In X-linked hyper-IgM (X-HIgM) syndrome, B cells are intrinsically normal but fail to receive the required CD40-CD154 costimulation to undergo GC reactions and are unable to generate T cell–dependent memory responses.4,5 However, a modestly mutated IgD+CD19+ population was reported in patients with X-HIgM syndrome with null CD154 mutations.5,6 The explanation for the appearance of B cells with mutated Ig genes in the absence of GCs remains controversial. It was suggested that the IgD+CD19+ mutated cells that reside within the CD27+ subset may be increased in frequency and represent a circulating splenic marginal zone population,7 although others have reported no elevation of circulating CD27+ cells in X-HIgM.8 Alternatively, antigen-activated B cells may start mutating before a GC reaction.9,10 Thus, the mutations found in X-HIgM B cells could represent the pre-GC or an extra-GC component of SHM

Whereas the mutational pattern of GC experienced normal peripheral memory B cells has been well characterized,11 the spectrum of mutations that develop in the absence of GCs is not known. The goal of this analysis, therefore, was to compare the features of normal peripheral blood (PB) B-cell mutations with those that occur in the absence of CD40-CD154 interactions and GCs to gain further insight into the nature of SHM and the B cells that undergo SHM in X-HIgM.

Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AICDA) plays an essential role in SHM.12,13 Although AICDA was originally considered GC B cell–specific, AICDA expression can be induced by signaling through various receptors that activate NF-κB, such as the CD40, TLR, and LPS pathways.12,14,15 It can be up-regulated in human PB B cells stimulated in vitro with combinations of anti-IgM or anti-CD40 with IL-21 stimulation16 and is expressed by extrafollicular large proliferating B cells.17,18 AICDA is expressed in Peyer patch lymphocytes from CD40−/− mice19 as well as intestinal lymphocytes from CD40-deficient humans,20 and it is most likely expressed in activated X-HIgM B cells that are intrinsically normal. Notably, AICDA is not constitutively expressed by human B cells residing in the marginal zone of the human spleen.21 This raises the question as to the nature and patterns of mutations in X-HIgM CD27+ B cells, especially if they possibly originate from marginal zone cells in response to T-independent antigens.7,22

The hallmark of SHM is the increased percentage of mutations in hypermutable RGYW (underlined residue is the most frequently mutated) motifs.23 Subsequently, the mutation frequency of WRCY motifs, the reverse complement of RGYW, was noted to be similar to that of RGYW24 and more recently this motif was recognized as the target of AICDA.13 The G/C mutation spectrum in SHM is thought to be the direct consequence of AICDA deamination of C residues in WRC motifs13 on the nontranscribed strand25 during transcription26 as well as on the transcribed strand.27-29

Despite the central role of AICDA in G/C mutations, during SHM nearly half of the mutations target A and T residues.11 The A/T mutation spectrum is associated with mismatch repair using MSH2-MSH628,30-33 and exonuclease 134 which normally provides high-fidelity repair that presumably becomes mutagenic in GC B cells with the recruitment of error-prone polymerase eta (POL η)35,36 targeting WA motifs. POL η deficiency results in a mutational pattern lacking targeting to WA motifs.37,38 Therefore, POL η appears to account for most WA mutations that can comprise as much as 25% of total nucleotide substitutions.37

Finally, the action of uracil–DNA glycosylase (UNG) appears to account for the introduction of transversions. This enzyme deletes AICDA-induced uracil and initiates translesion synthesis (TLS) involving mechanisms that generate transversions that do not occur when high-fidelity polymerase recognizes the dU/dG mismatch as dT.39

The present study involved a detailed mutation analysis of PB B cells from 4 young and 3 adult patients with X-HIgM syndrome to characterize the mutation patterns that develop in the absence of CD154 stimulation and GC reactions. We were particularly interested in mutations in nonproductive heavy and light chain rearrangements because these are not influenced by selection.11 Because AICDA and POL η generate mutations in specific nucleotide motifs and UNG2 is involved in the generation of transversions, we focused on analyzing these specific features of mutational targeting to determine the frequency and nature of the mutations occurring in X-HIgM B cells. The results indicate that mutational targeting in X-HIgM are significantly different from that noted in normal memory B-cell populations, consistent with the conclusion that SHM in X-HIgM reflects an extra- or pre-GC process characterized by relatively decreased activity of AICDA and UNG compared with that characteristic of GC reactions.

Methods

Tissue sources

PB was obtained from a male patient with X-HIgM at 9 and 13 years of age who has 2 mutations, one of which introduces a stop codon in the CD40 ligand gene40 and whose repertoire was previously analyzed at the age of 4 years.5 Other patients with X-HIgM included a 7-, 8-, and 12-year-old and 3 adults approximately 20 years old. Genetic phenotyping and clinical manifestations of these patients were reported.41 Apheresis of healthy donors, and 6 tonsil specimens from children aged 2 to 10 years were obtained with approval of the Institutional Review Board of the National Institutes of Health approval and informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Tissue processing

PB mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from PB or splenic cells diluted in PBS using Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) separation. For microarray analysis, B cells were negatively selected using an EasySep magnetic column (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC) following the manufacturer's instructions. Purity was greater than 95%. Tonsils were minced and digested in RPMI medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) containing 210 U/mL collagenase type I (Worthington Biochemical Corp, Lakewood, NJ) and 90 U/mL DNase (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) for 30 minutes at 37°C. After filtration through a wire mesh, the cells were washed twice in 20% FBS/RPMI and once in 10% FBS/RPMI before centrifugation over diatrizoate/Ficoll gradients.

Flow cytometric separation and analysis of B-cell subpopulations

Cells were stained with the following fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies: mouse IgG1 anti–human CD19 PE (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ), mouse IgG2 anti–human IgD FITC (PharMingen, San Diego, CA) or goat anti–human IgD FITC (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), anti-CD38 APC (BD Biosciences) and anti–CD27-PE and isotype controls (Becton Dickinson PharMingen, San Diego, CA). 7-Aminoactinomycin (7-AAD; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was used to exclude dead cells. PB and splenic cells were sorted according to CD19 and IgD or CD19, IgD, and CD27 expression, respectively. CD19+ tonsillar B cells were sorted into subsets of naive CD38−IgD+, pre-GC founder CD38++IgD+, and GC CD38++IgD− cells. Sorting was performed on a Becton Dickinson fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) Vantage SE DiVa or a MoFlo Cell Sorter (Dako). Additional samples were collected for analysis on a FACS Calibur (Becton Dickinson) or CyAN (Dako Colorado, Fort Collins, CO) and analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar, Stanford University, CA), Paint-a-Gate (Becton Dickinson), CellQuest (Becton Dickinson), and Summit (Dako Colorado).

Lysate preparation and single-cell PCR

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of VH genes obtained from genomic DNA of individual B cells was carried out as described previously.42 The PCR error established for this method is approximately 6 mutations per 75 000 base pairs analyzed (0.008%).43,44 This PCR error rate indicates that the maximal number of PCR-induced base pair changes in the nonproductive X-HIgM repertoire was 3.

Database and sequence analysis

Germ line sequences of nonproductive and productive rearrangements were determined by using the JOINSOLVER sequence analysis program.45 The normal donor (ND) rearrangements analyzed included 71 nonproductive and 414 productive CD19+ rearrangements (GenBank Nos. X87006-X8708246 (one donor) and Z80363-Z80770 (2 donors),47 20 nonproductive and 128 productive IgD+CD27+ (EF542547-EF542687), and 12 nonproductive and 100 productive IgD−CD27+ (EF542688-EF542796) rearrangements (one donor). The CD19+ data from patients with X-HIgM included 209 nonproductive and 926 productive rearrangements from a patient at age 4 (AF077410-AF077525)5 and 9 (EF542103-EF542275) years, 3 other children with X-HIgM at ages 7 to 12 (EF541488-EF542102) and 3 adults with X-HIgM (EF542315-EF542546). The IgD+CD27+ X-HIgM repertoire consisting of 7 nonproductive and 32 productive rearrangements (EF542276-EF542314) were from a 13-year-old patient who was also analyzed at ages 4 and 9. From the 9-year-old patients with X-HIgM, 72 nonproductive and 53 productive light chain rearrangements were analyzed (EU875398-EU875522).

Seven new polymorphisms within codons 25 to 94 in 6 VH genes were identified from the X-HIgM B cells and were not included in the mutation analysis. The 16 germ line VH genes used in the mutated nonproductive X-HIgM repertoire were used to calculate the expected replacement-to-silent (R/S) ratios from the codons within FRS4, FRS2, and FRS3 (R/S = 3.2) and the codons from CDR1 and CDR2 (R/S = 4.5).

No gross abnormalities were noted in the repertoire that could contribute to an abnormal mutation pattern (data not shown).

Statistical analysis

Differences between the mutation pattern of patients with X-HIgM and NDs were determined by using the chi-square test for 2 × 2 tables with and without Yates correction. The chi-square test was valid because the total number of mutations in the nonproductive (n = 51) and productive (n = 251) repertoire was more than 40.48,49

The standard error was propagated for mutational targeting of the hypermutable nucleotide inside versus outside a motif using the formula s = where P is the proportion of mutated bases either inside or outside the hypermutable position and n is the number of bases (either mutated or unmutated) at the hypermutable position. The standard error of the fold difference is given by the formula where Pin (Pout) is the proportion of mutated bases inside (outside) the hypermutable position with standard error sin (sout). Hypothesis testing was performed to compare the fold difference between patients with X-HIgM and NDs and to determine whether the observed frequency of random mutations was significantly different from the expected frequency. A 2-sigma confidence interval, which corresponds to a P value slightly smaller than .05 surrounding the mean, was used as the nonrejection region. For all statistical analyses P values less than the .05 limit were used to determine significant differences.

Microarray analysis of gene expression

Total RNA was isolated from B cells using TRIZOL (Invitrogen), purified using RNeasy mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), processed for microarray analysis using standard Affymetrix protocols (www.affymetrix.com), and hybridized to HG-U133A Affymetrix Genechips. Genechips (Affymetrix) were scanned on a high-resolution Affymetrix scanner using GCOS version 1.2 software. In addition, naive and GC cells from 3 additional tonsils were profiled for gene expression using the Affymetrix U133plus 2.0 array. To determine changes in gene expression, the microarray signals from tonsillar naive B cells (CD38−IgD+) were compared with activated naive/pre-GC founder cell (CD38++IgD+) and tonsillar GC cell (CD38++IgD−) signals. Data were normalized according to standard Affymetrix algorithm analysis (MAS5) by scaling the median expression to 500, using methods identical to those described previously.50 The raw data were log2 transformed and entered into a database. Array elements with median signal intensities of less than 6 log2 units across the samples (approximately 25% of array elements) were removed from the analysis entirely to exclude poorly measured genes and genes not appreciably expressed in a sample. The array data were also reanalyzed after normalization with the RMA algorithm.51 The data were deposited in the publicly available database GEO (accession nos. GSE12845, submitted September 18, 2008, and GSE12366, submitted August 6, 2008).52 For comparison of genes in different subpopulations or genes affected by CD154 treatment a 2-tailed Student t test was applied to individual comparisons. Both a 1.4-fold change or greater and a P value less than .05 were considered significant. Further analyses were performed using a hierarchical clustering algorithm53 to group genes according to similar expression levels.

Results

Mutation frequency of X-HIgM B cells

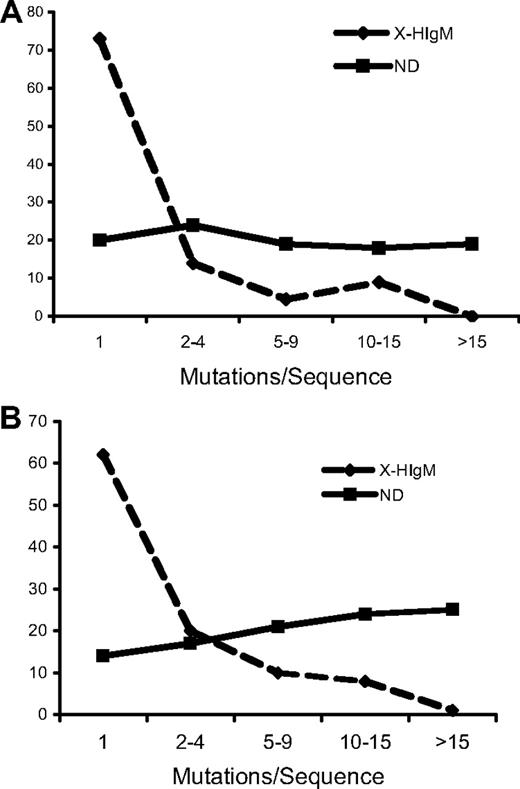

Initially, the mutation frequency of VH genes was assessed for comparison between children and adults with X-HIgM. In a ND, 85% of the nonproductive Ig rearrangements in CD19+ B cells was mutated compared with only 10% in patients with X-HIgM aged 7 to 12 years, 1% in the 9-year-old patient with X-HIgM, and 4% in adult patients with X-HIgM (Table 1). Although the 4-year-old patient with X-HIgM had more mutated rearrangements (6 of 23; 26%) than all other patients with X-HIgM, the frequency of mutated sequences 5 years later had fallen closer to the level of others in his age group and the adults. The overall mutation frequency of nonproductive rearrangements from all patients with X-HIgM was 0.2% plus or minus 0.03% (mean ± SEM) compared with 3.8% in the ND CD19+ cells. Even when only the mutated nonproductive sequences were considered, there was a significant reduction in the X-HIgM versus normal (0.9% ± 0.4% vs 4.5%; P < .001). Although the mutation frequency is low, it is significantly greater than the PCR error (0.008%; P < .001) established for this method.42 In the productive repertoire, adult patients had the highest overall mutation frequency among the patients with X-HIgM. However, it was greater than 10-fold less (0.2% vs 2.5%) than the overall mutation frequency of normal CD19+ cells. Moreover, the mutational frequency of just those sequences with mutated VH rearrangements was almost 3-fold (1.2% versus 3.3%) less than the mutation frequency of healthy adult mutated sequences. As opposed to NDs, most mutated X-HIgM sequences contained only a single mutation (Figure 1). Similar results were observed when light chain mutations were analyzed (Table S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Of the 15 872 base pairs analyzed in nonproductive light chain rearrangements, there were 26 mutations for an overall mutational frequency of 0.2%. This is significantly (P < .001 with Yates correction) lower than the mutational frequency of normal light chains as previously reported.54,55

The mutation frequency of heavy chain rearrangements from IgD+CD19+ B cells of individual patients with X-HIgM of different ages

| . | 4-year-old X-HIgM . | 9-year-old X-HIgM . | 7- to 12-year-old X-HIgM . | Adult X-HIgM . | ND adult . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP . | P . | NP . | P . | NP . | P . | NP . | P . | NP . | P . | |

| Total no. of rearrangements | 23 | 92 | 31 | 143 | 104 | 509 | 51 | 182 | 13 | 69 |

| Percentage of mutated rearrangements (%) | 6/23 (26)* | 14/92 (15) | 3/331 (1) | 11/143 (8) | 10/104 (10) | 38/509 (8) | 2/51 (4) | 17/182 (9) | 11/13 (85)* | 53/69 (77) |

| Total no. of mutations | 10 | 18 | 3 | 11 | 14 | 103 | 11 | 48 | 126 | 440 |

| Overall mutation frequency (%) | 10/5814 (0.2)† | 18/23208 (0.08) | 3/6540 (0.05) | 11/31315 (0.04) | 14/22461 (0.06) | 103/100669 (0.1) | 11/11345 (0.1) | 48/40687 (0.2) | 126/3330 (3.8)† | 440/17579 (2.5) |

| Mutation frequency of mutated rearrangements (%) | 10/1524 (0.7) | 18/3540 (0.6) | 3/644 (0.5) | 11/2377 (0.5) | 14/2022 (0.7) | 103/7548 (1.4) | 11/465 (2.4)‡ | 48/4126 (1.2) | 126/2826 (4.5)‡ | 440/13484 (3.3) |

| . | 4-year-old X-HIgM . | 9-year-old X-HIgM . | 7- to 12-year-old X-HIgM . | Adult X-HIgM . | ND adult . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP . | P . | NP . | P . | NP . | P . | NP . | P . | NP . | P . | |

| Total no. of rearrangements | 23 | 92 | 31 | 143 | 104 | 509 | 51 | 182 | 13 | 69 |

| Percentage of mutated rearrangements (%) | 6/23 (26)* | 14/92 (15) | 3/331 (1) | 11/143 (8) | 10/104 (10) | 38/509 (8) | 2/51 (4) | 17/182 (9) | 11/13 (85)* | 53/69 (77) |

| Total no. of mutations | 10 | 18 | 3 | 11 | 14 | 103 | 11 | 48 | 126 | 440 |

| Overall mutation frequency (%) | 10/5814 (0.2)† | 18/23208 (0.08) | 3/6540 (0.05) | 11/31315 (0.04) | 14/22461 (0.06) | 103/100669 (0.1) | 11/11345 (0.1) | 48/40687 (0.2) | 126/3330 (3.8)† | 440/17579 (2.5) |

| Mutation frequency of mutated rearrangements (%) | 10/1524 (0.7) | 18/3540 (0.6) | 3/644 (0.5) | 11/2377 (0.5) | 14/2022 (0.7) | 103/7548 (1.4) | 11/465 (2.4)‡ | 48/4126 (1.2) | 126/2826 (4.5)‡ | 440/13484 (3.3) |

The data for the 4-year-old and 9-year-old are from the same patient after a 5-year interval. The data from 3 different patients were combined in each of the 7- to 12-year-old and adult X-HIgM categories. The normal donor data include GenBank accession nos. X87006-87089 (excluding X87017 and X87083). The mutation frequencies were calculated from the number of mutations/total number of bases analyzed and from the total number of bases analyzed from mutated sequences only.

ND indicates normal donor; NP, nonproductive rearrangement; and P, productive rearrangement.

Significant (P ≤ .03) difference in the percentage of mutated NP rearrangements from 4-year-old X-HIgM versus other X-HIgM and ND versus all X-HIgM.

Significant (P < .05) difference in the overall mutation frequency of NP rearrangements from 4-year-old X-HIgM versus all other X-HIgM and ND versus all X-HIgM.

Significant (P < .005) difference in the mutation frequency of mutated NP rearrangements from ND versus all 4- to 12-year-old X-HIgM and adult X-HIgM versus other X-HIgM.

Nonproductive and productive repertoires in X-HIgM are significantly less mutated than NDs. All mutations in X-HIgM and NDs were grouped according to the number of mutations/mutated sequence. (dashed line indicates X-HIgM; solid line, NDs). (A) Nonproductive repertoire, (B) productive repertoire.

Nonproductive and productive repertoires in X-HIgM are significantly less mutated than NDs. All mutations in X-HIgM and NDs were grouped according to the number of mutations/mutated sequence. (dashed line indicates X-HIgM; solid line, NDs). (A) Nonproductive repertoire, (B) productive repertoire.

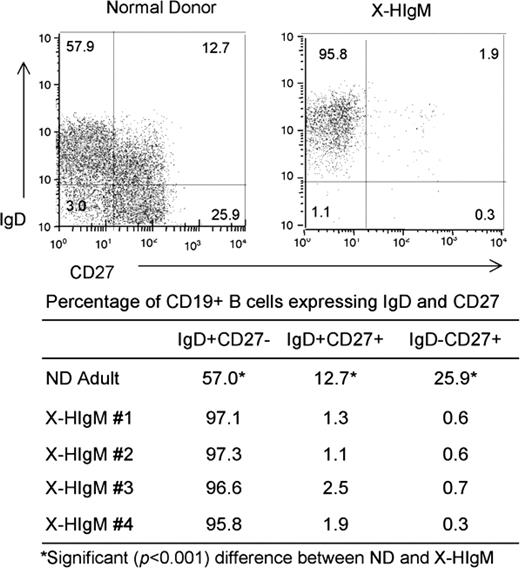

The size of the IgM+IgD+CD27+ memory B-cell population and its origin in patients with X-HIgM is controversial.6-8 We, therefore, analyzed the frequency of CD27+ memory B cells in an ND and 4 patients with X-HIgM of various ages. In these patients with X-HIgM, less than 3% of the CD19+ population was CD27+, significantly (P < .001 with Yates correction) less than the CD27+ population in NDs (Figure 2). Notably, the postswitch IgD−CD27+ population was the most markedly deficient (26% in ND versus 0.6% in X-HIgM). To examine the mutational status of CD27+ cells in X-HIgM, we sequenced 78 VH rearrangements obtained from IgD+CD27+ cells of a 13-year-old patient with X-HIgM previously analyzed at ages 4 and 9 years, and we compared them to VH rearrangements from 148 preswitched (IgD+CD27+) memory B cells of a healthy young adult. In NDs, 90% to 98% of the nonproductive and productive CD27+IgD+ preswitched memory cells expressed mutated VH genes (Table S2).56 In X-HIgM, only 1 of 7 IgD+CD27+ B cells expressed mutated VH genes in the nonproductive repertoire and in the productive repertoire 12 (38%) of 32 were mutated (data not shown). The overall mutation frequency of nonproductive (13 of 1496; 0.9%) and productive (73 of 7809; 0.9%) rearrangements from X-HIgM IgD+CD27+ B cells was significantly less than the mutation frequency of rearrangements from normal IgD+CD27+ memory B cells (160 of 3694; 4.3%; P < .001). As a result, the IgD+CD27+ and IgD+CD19+ X-HIgM repertoires were dominated by sequences with 0 to 5 mutations, whereas the ND IgD+CD27+ repertoire was enriched in sequences with 5 or more mutations per sequence. Because the X-HIgM IgD+CD27+ rearrangements were similar in mutation frequency to the X-HIgM mutated IgD+CD19+ rearrangements and recent evidence has identified a CD27− human memory B-cell population,57-59 the X-HIgM data were combined to compare all mutations with similarly pooled ND B-cell subsets (Table S3). Note that the mutation frequency and the targeting of mutations to specific motifs (see “Mutation focusing in hot spots”) were similar in X-HIgM nonproductive and productive repertoires, indicating that there was minimal selection of these mutations.

CD27+ B cells are decreased in X-HIgM. PBMCs from patients with X-HIgM and NDs were stained with CD19, IgD, and CD27 fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry using CELLQuest software. The percentage of naive (CD19+IgD+CD27−), preswitch (CD19+IgD+CD27+), and postswitch (CD19+IgD−CD27+) cells represent the data analyzed from four 7- to 13-year-old patients with X-HIgM and 4 NDs. *Significant (P < .001) difference in the percentage of cells between ND and X-HIgM.

CD27+ B cells are decreased in X-HIgM. PBMCs from patients with X-HIgM and NDs were stained with CD19, IgD, and CD27 fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry using CELLQuest software. The percentage of naive (CD19+IgD+CD27−), preswitch (CD19+IgD+CD27+), and postswitch (CD19+IgD−CD27+) cells represent the data analyzed from four 7- to 13-year-old patients with X-HIgM and 4 NDs. *Significant (P < .001) difference in the percentage of cells between ND and X-HIgM.

Mutation focusing in hot spots

In X-HIgM, RGYW and WRCY motifs were mutated. No significant differences were found between the percentage of mutations in the nonproductive X-HIgM RGYW and WRCY motifs in comparison to that expected from random chance (12.5%) (Table 2), and no significant differences were found (P = .16) between X-HIgM and ND nonproductive or productive repertoires. A and T mutations in WA and TW motifs, reflecting the effect of POL η activity, were also similar in X-HIgM and NDs. Consistent with the preferential targeting of WA motifs by POL η,60 the mutations in TA motifs significantly exceeded that expected from random chance (6.35%) and other dinucleotides of WA/TW in NDs (71.4 of 593; 12%; P < .001) and, although not significantly greater, a trend for an increase in TA mutations occurred in X-HIgM (data not shown). Notably, 64% of the mutations in the nonproductive X-HIgM repertoire could be accounted for by mutations in RGYW/WRCY or WA/TW compared with 73% in NDs.

Frequency and distribution of individual nucleotide mutations

| . | X-HIgM . | Normal donors . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP . | P . | NP . | P . | |

| RGYW (%) | 8.5/51 (17) | 56.5/250 (23)* | 147/593 (25)* | 1227.3/4857 (25)* |

| WRCY (%) | 9.5/51 (19) | 31.5/250 (13) | 84/593 (14) | 697.5/4857 (14) |

| WA (%) | 8/51 (16)† | 54/250 (22)‡ | 137.4/5933 (23)‡ | 890.5/4857 (18)‡ |

| TW | 6/51 (12) | 22/250 (9) | 66.7/593 (11) | 488.5/4857 (10) |

| FR (R/S) | 21/12 (1.8) | 114/50 (2.3) | 304/92 (3.3)§ | 1961/1155 (1.7) |

| CDR (R/S) | 14/4 (3.5) | 68/20 (3.4) | 166/29 (5.7)‖ | 1347/394 (3.4) |

| Transitions (%) | 33/51 (65)¶ | 140/250 (56) | 302/593 (51) | 2626/4857 (54) |

| Transversions (%) | 18/51 (35) | 110/250 (44) | 291/593 (49) | 2231/4857 (46) |

| . | X-HIgM . | Normal donors . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP . | P . | NP . | P . | |

| RGYW (%) | 8.5/51 (17) | 56.5/250 (23)* | 147/593 (25)* | 1227.3/4857 (25)* |

| WRCY (%) | 9.5/51 (19) | 31.5/250 (13) | 84/593 (14) | 697.5/4857 (14) |

| WA (%) | 8/51 (16)† | 54/250 (22)‡ | 137.4/5933 (23)‡ | 890.5/4857 (18)‡ |

| TW | 6/51 (12) | 22/250 (9) | 66.7/593 (11) | 488.5/4857 (10) |

| FR (R/S) | 21/12 (1.8) | 114/50 (2.3) | 304/92 (3.3)§ | 1961/1155 (1.7) |

| CDR (R/S) | 14/4 (3.5) | 68/20 (3.4) | 166/29 (5.7)‖ | 1347/394 (3.4) |

| Transitions (%) | 33/51 (65)¶ | 140/250 (56) | 302/593 (51) | 2626/4857 (54) |

| Transversions (%) | 18/51 (35) | 110/250 (44) | 291/593 (49) | 2231/4857 (46) |

The X-HIgM data include 104 productive (P) and 24 nonproductive (NP) CD19+IgD+ and CD19+CD27+ mutated rearrangements. Normal donor populations include 483 P and 69 NP CD19+IgM+, IgD+CD27+, and IgD−CD27+ mutated rearrangements.

FR indicates framework region; CDR, complementarity determining region; R/S indicates replacement-to-silent mutation ratio. All positions of the motif were included for mutation analysis. AGCT motifs with a mutated G but not C were considered RGYW motif mutations. AGCT motifs with a mutated C but not G were considered WRCY motif mutations. Three ambiguous A or T mutations in AGCT motifs with neither G or C mutations were scored as a mutation in RGYW and WRCY motifs.

Significant (P < .05) difference between RGYW and WRCY mutations.

Significant (P = .03) difference between X-HIgM and normal donors nonproductive rearrangements.

Significantly (P = .05) greater mutation frequency compared with the expected random frequency.

Significant (P < .05) difference between the NP and P FR R/S of ND.

Significant (P = .02) difference between the NP FR R:S and NP CDR R:S of ND.

Significant (P = .03) difference between the percentage of transitions versus transversions.

Some differences between X-HIgM and NDs became apparent by examining the ratio of replacement (R) to silent (S) mutations. Notably, the R/S ratios in the complementarity determining regions (CDRs) and framework regions (FRs) of nonproductive X-HIgM rearrangements were approximately half as great as in NDs. Unlike NDs, no significant difference was found between the FR and CDR R/S ratios (Table 2). Finally, in contrast to NDs in which R mutations in the CDRs are eliminated from the productive repertoire (P = .013; with Yates correction P = .17),61 no significant difference was found in the CDR R/S ratios between the nonproductive and productive repertoire of X-HIgM B cells.

Transition substitutions dominate in X-HIgM

X-HIgM B cells also have an abnormal ratio of transitions to transversions. Although the ratio of transition to transversion substitution would be 1:2 if these occurred randomly, transitions were nearly as common as transversions in normal B-cell SHM (Table 2). In contrast, in the nonproductive X-HIgM repertoire, transitions were favored (33:18 or 1.8:1). A similar finding was noted with light chain mutations in which transitions dominated (18:8 or 2.3) (Table S1). When both heavy and light chain mutations were considered, there was a significant difference in their distribution in X-HIgM versus normal (51 transitions:26 transversions in X-HIgM versus 499 transitions:484 transversions in normal; P = .008; P = .01 with Yates correction). Transitions tended to be negatively selected in X-HIgM VH genes and, as a result the ratio of transitions to transversions in the productive X-HIgM repertoire, was closer to normal (1.3:1).

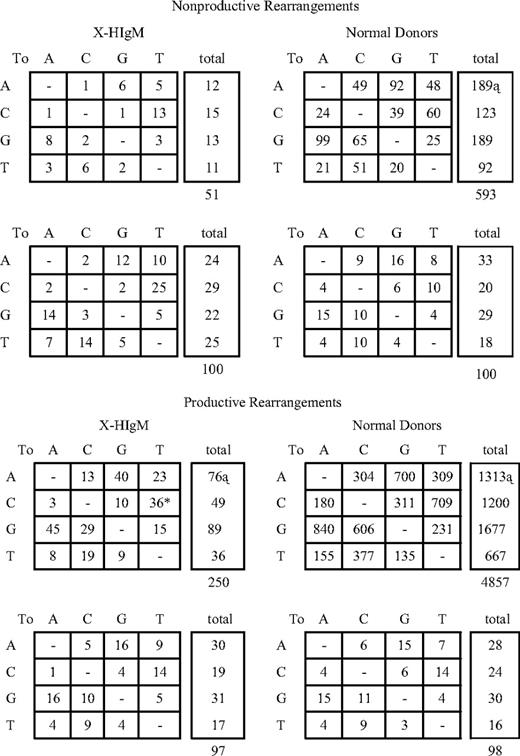

To examine the increased frequency of transitions over transversions in X-HIgM in more detail, point mutations of individual nucleotides in X-HIgM rearrangements were analyzed. The increase in total transitions in X-HIgM versus normal nonproductive rearrangements were biased toward an increased presence of C→T transitions (Figure 3A). (In X-HIgM, 13 of the 51 mutations [25%] were C→T substitutions compared with 60 of 593 [10%] in NDs.) Within the population of C mutations in the heavy chain (HC) repertoire, significantly (P = .005 or .01 with Yates correction) more transitions than transversions were found in X-HIgM compared with NDs (13 C > T/2 C transversions versus 60 C > T/63 transversions, respectively). A significant difference (P = .04) was also noted in the productive repertoire in which 36 (73%) of 49 C mutations were C→T transitions (Figure 3B).

Cytosine-to-thymine transition substitutions are increased in X-HIgM B cells. The number (first row) and percentage (second row) of individual nucleotide substitutions detected in the variable segment of (A) nonproductive and (B) productive VDJH rearrangements in PB B cells from 4 NDs and 7 patients with X-HIgM are presented. The tables representing the percentages of all mutations scored are corrected for base composition of the target sequence. *Significant difference in C > T transitions; †significant difference in G versus C mutation frequency; ‡significant difference in A versus T mutation frequency.

Cytosine-to-thymine transition substitutions are increased in X-HIgM B cells. The number (first row) and percentage (second row) of individual nucleotide substitutions detected in the variable segment of (A) nonproductive and (B) productive VDJH rearrangements in PB B cells from 4 NDs and 7 patients with X-HIgM are presented. The tables representing the percentages of all mutations scored are corrected for base composition of the target sequence. *Significant difference in C > T transitions; †significant difference in G versus C mutation frequency; ‡significant difference in A versus T mutation frequency.

Targeting the hypermutable G/C in RGYW/WRCY motifs

Because AICDA is known to target the C in WRCY motifs, we examined the specific targeting of G/C in RGYW/WRCY motifs as a fingerprint of AICDA activity. Initially, the distribution of individual nucleotide mutations was analyzed in the nonproductive repertoire of X-HIgM. Mutations in all 4 nucleotides were comparable (Figure 3A). In contrast, NDs mutate A or G > C > T and exhibit significant G versus C (P < .001) and A versus T (P < .001) strand bias in both nonproductive and productive repertoires. In X-HIgM, there is a bias favoring A mutations more than T mutations (P < .001) and G mutations more than C mutations (P < .001) only in the productive repertoires, presumably as a consequence of selection (Figure 3B).

Even though the percentage of mutations in RGYW/WRCY motifs was comparable to NDs, the abnormal nucleotide substitution pattern prompted an analysis of mutations in specific residues in these motifs to assess the relative activity of AICDA in X-HIgM. The mutation frequency of the hypermutable nucleotide (C or G) in the targeted motifs (WRCY or RGYW, respectively) was compared with the mutation frequency of the same nucleotide occurring elsewhere in the variable segment. Marked differences were noted when an analysis of G mutations in the second position of RGYW motifs was carried out (Table 3). In normal B cells, the mutation frequency of G nucleotides in RGYW was 5.5- to 6.5-fold greater than those outside RGYW in productive and nonproductive repertoires, respectively. In contrast, in the nonproductive X-HIgM repertoire, targeted mutation of the hypermutable G in RGYW motifs was absent because the frequency of G mutation inside RGYW was no greater than the frequency of mutation outside RGYW (0.11% and 0.09%, respectively). The possibility that the difference in the distribution of G mutation between X-HIgM and NDs was related to random chance was highly unlikely because the fold difference comparing G mutations in and out of RGYW motifs in X-HIgM versus NDs was 1.25 ± 0.97 versus 6.48 ± 0.9, respectively (P < .001). Even though there was evidence of selection of G mutations within RGYW in the X-HIgM productive repertoire, the fold increase in G mutations within RGYW compared with those outside RGYW remained significantly less than in the normal productive repertoire (2.7 vs 5.4; P < .001). A loss of hypermutable G mutations in RGYW motifs was also noted in the nonproductive light chains (Table S1).

Target nucleotide mutation frequency (%) in hypermutable motifs

| Mutated base and motif . | X-HIgM . | Normal donor . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP . | P . | NP . | P . | |

| G | ||||

| Inside RGYW | 2/1770 (0.11) | 25.5/7730.5 (0.29)* | 92/832 (11.06)* | 757/5618 (13.47)* |

| All other G | 11/12258 (0.09) | 62.5/51099.5 (0.12) | 102/5984 (1.70) | 950/38080 (2.49) |

| C | ||||

| Inside WRCY | 7.5/1504 (0.50)*† | 12.5/6392.5 (0.20)* | 60/736 (8.15)* | 445/4561 (9.76)* |

| All other C | 7.5/11034 (0.07) | 39.5/46456 (0.09) | 76/5606 (1.36) | 782/35736 (2.19) |

| A | ||||

| Inside WA | 8/5370.75 (0.10) | 54/22097 (0.24)* | 133.25/2463.25 (5.41)*† | 913.8/15111 (6.05)* |

| All other A | 5/7263.25 (0.07) | 22/30527 (0.07) | 55.75/3412.75 (1.63) | 436.2/22300 (1.96) |

| T | ||||

| Inside TW | 6/2480 (0.24)* | 22/13866 (0.16)* | 59.5/1531.25 (3.89)* | 498.5/10008.5 (4.98)* |

| All other T | 5/7788 (0.06) | 12/29179 (0.04) | 44.5/3586.75 (1.24) | 175.5/22503.5 (0.78) |

| A | ||||

| Inside RGYW | 3.75/1483.25 (0.25)* | 15/6545.5 (0.23)* | 34/719.25 (4.73)* | 291/4701.3 (6.19)* |

| All other A | 8.25/11150.75 (0.07) | 61/46078.5 (0.13) | 155/5156.75 (3.01) | 1059/32709.7 (3.24) |

| A | ||||

| Inside WRCY | 1.25/1678.75 (0.07) | 9/7172.5 (0.13) | 27/804.75 (3.36) | 197/4967.8 (3.97) |

| All other A | 10.75/10955.25 (0.10) | 67/45451.5 (0.15) | 162/5071.25 (3.19) | 1153/32443 (3.56) |

| Mutated base and motif . | X-HIgM . | Normal donor . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP . | P . | NP . | P . | |

| G | ||||

| Inside RGYW | 2/1770 (0.11) | 25.5/7730.5 (0.29)* | 92/832 (11.06)* | 757/5618 (13.47)* |

| All other G | 11/12258 (0.09) | 62.5/51099.5 (0.12) | 102/5984 (1.70) | 950/38080 (2.49) |

| C | ||||

| Inside WRCY | 7.5/1504 (0.50)*† | 12.5/6392.5 (0.20)* | 60/736 (8.15)* | 445/4561 (9.76)* |

| All other C | 7.5/11034 (0.07) | 39.5/46456 (0.09) | 76/5606 (1.36) | 782/35736 (2.19) |

| A | ||||

| Inside WA | 8/5370.75 (0.10) | 54/22097 (0.24)* | 133.25/2463.25 (5.41)*† | 913.8/15111 (6.05)* |

| All other A | 5/7263.25 (0.07) | 22/30527 (0.07) | 55.75/3412.75 (1.63) | 436.2/22300 (1.96) |

| T | ||||

| Inside TW | 6/2480 (0.24)* | 22/13866 (0.16)* | 59.5/1531.25 (3.89)* | 498.5/10008.5 (4.98)* |

| All other T | 5/7788 (0.06) | 12/29179 (0.04) | 44.5/3586.75 (1.24) | 175.5/22503.5 (0.78) |

| A | ||||

| Inside RGYW | 3.75/1483.25 (0.25)* | 15/6545.5 (0.23)* | 34/719.25 (4.73)* | 291/4701.3 (6.19)* |

| All other A | 8.25/11150.75 (0.07) | 61/46078.5 (0.13) | 155/5156.75 (3.01) | 1059/32709.7 (3.24) |

| A | ||||

| Inside WRCY | 1.25/1678.75 (0.07) | 9/7172.5 (0.13) | 27/804.75 (3.36) | 197/4967.8 (3.97) |

| All other A | 10.75/10955.25 (0.10) | 67/45451.5 (0.15) | 162/5071.25 (3.19) | 1153/32443 (3.56) |

The data include all nonproductive and productive mutations in patients with X-HIgM and normal donors. The targeted nucleotide refers to the base in the underlined position (or two positions; eg, A in the first and second position in the WA motif where W indicates A or T). The mutation frequency of the targeted nucleotide inside a motif equals the number of target nucleotide mutations/the total number of the nucleotide in the motif. The nucleotide mutation frequency outside the motif targeted position(s) equals (the total number of specific base mutations in the sequence − the number of targeted nucleotide mutations in the motif)/(the total number of the base in the sequence − the number of target nucleotides inside the motif). The extent of targeting was determined by calculating the fold difference between the mutation frequency inside versus outside a motif.

Significant (P < .02) difference in the nucleotide mutation frequency inside a motif versus outside a motif.

Significant (P < .02) difference in the nucleotide mutation frequency in nonproductive versus productive rearrangements.

In contrast, pronounced targeting of C mutation in WRCY was found in X-HIgM as well as in normals in the nonproductive and productive repertoires. In normal B cells, the difference in the mutation frequency of C inside WRCY versus all other C mutations was 4.4-fold in nonproductive rearrangements. Similarly, of the 15 C mutations in X-HIgM, half occurred in the hypermutable position of WRCY, resulting in a 7-fold greater C mutational frequency inside WRCY versus all other C mutations (0.5% versus 0.07%; P < .001 with or without Yates correction). In the nonproductive light chain rearrangements, there was greater than 3-fold more hypermutable C targeting in WRCY compared with all other C mutations (Table S1).

Analysis of mutations in the other 3 positions of R–YW motifs in the nonproductive X-HIgM repertoire showed a 3.6-fold increase in the frequency of A mutations inside RGYW (0.25%) compared with outside RGYW (0.07%), most of which were in overlapping WA/TW motifs. In sharp contrast, A mutations inside and outside WRCY were equal. A similar pattern was noted in normals. Although WA mutations were found preferentially in RGYW motifs, there were numerous WA mutations outside RGYW/WRCY.

Gene expression profiling of GC B cells

The multiple mutation abnormalities in X-HIgM B cells, which include a decreased frequency of SHM, decreased frequency of G mutation in RGYW and decreased transversion substitutions, suggested CD40-CD154 signaling may regulate expression of genes involved in mutational targeting or DNA repair. To address this question, gene expression profiles were analyzed from tonsil B-cell subsets, including naive B cells (CD19+CD38−IgD+), pre-GC B cells (CD19+CD38++IgD+), and GC B cells (CD19+CD38++IgD−), as well as PB naive (CD19+CD27+) or memory (CD19+CD27−) B cells (Table 4; Figures S1Figure S2. A single node from the Fig. S1 dendogram reveals a tight cluster of genes upregulated in GC B cells (JPG, 391 KB)–S3).

Gene expression levels in normal donor B cell populations

| Up-regulated . | Fold change . | Down-regulated . | Fold change . | No change . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tonsil IgD+CD38++ cells | ||||

| AICDA* | 4.9 | CR2 | 1.5 | TNFRSF7 (CD27) |

| APEX2* | 1.5 | CD40* | 1.5 | POL ζ (XPV) |

| CD38* | 4.4 | MBD4 | 1.7 | POLζ (Rev3) |

| CD80 (B7-1) | 1.5 | PMSL2 and PMSL3 (PMS) | 1.6-2.7 | RPA |

| EXO1* | 4.6 | POL μ | 2.2 | XPA |

| FEN1* | 2.1-2.2 | SMUG1 | 1.8 | XPC |

| MLH1* | 1.6 | XPD | ||

| MME (CD10)* | 9.6-13 | KU70 (XRCC6) | ||

| MSH2* | 1.6 | KU80 (XRCC5) | ||

| MSH3 | 1.5 | LIG4 | ||

| MSH5 | 1.4-1.8 | |||

| MSH6* | 1.5-1.9 | |||

| NEIL1* | 2.9 | |||

| OGG1* | 2.0 | |||

| PCNA* | 2.5 | |||

| POL θ* | 2.1-2.6 | |||

| RAD50* | 1.4 | |||

| RAD51* | 4.2-6.5 | |||

| UNG* | 1.8 | |||

| UNG2 | 1.7 | |||

| XRCC4* | 1.0-5.2 | |||

| Tonsil IgD−CD38++ cells | ||||

| AICDA* | 15.4 | CR2* | 1.7 | POL ζ (Rev3) |

| CD38* | 8.8 | ERCC1* | 1.5 | XPA |

| CD80 (B7-1)* | 1.8 | MSH4* | 1.5 | XPC |

| EXO1* | 6.4 | POL ι | 1.5 | XPD |

| FEN1* | 2.8-3.5 | POL μ | 3.3 | KU70 (XRCC6) |

| MLH1* | 1.8 | POL η | 2.7 | KU80 (XRCC5) |

| MME (CD10)* | 35-44 | LIG4 | ||

| MSH2* | 2.1 | |||

| PCNA* | 3.7 | |||

| POL θ* | 1.6-3.7 | |||

| RAD51* | 6.2-11.9 | |||

| RPA* | 1.8 | |||

| TNFRSF7 (CD27)* | 3.1 | |||

| UNG* | 3.0 |

| Up-regulated . | Fold change . | Down-regulated . | Fold change . | No change . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tonsil IgD+CD38++ cells | ||||

| AICDA* | 4.9 | CR2 | 1.5 | TNFRSF7 (CD27) |

| APEX2* | 1.5 | CD40* | 1.5 | POL ζ (XPV) |

| CD38* | 4.4 | MBD4 | 1.7 | POLζ (Rev3) |

| CD80 (B7-1) | 1.5 | PMSL2 and PMSL3 (PMS) | 1.6-2.7 | RPA |

| EXO1* | 4.6 | POL μ | 2.2 | XPA |

| FEN1* | 2.1-2.2 | SMUG1 | 1.8 | XPC |

| MLH1* | 1.6 | XPD | ||

| MME (CD10)* | 9.6-13 | KU70 (XRCC6) | ||

| MSH2* | 1.6 | KU80 (XRCC5) | ||

| MSH3 | 1.5 | LIG4 | ||

| MSH5 | 1.4-1.8 | |||

| MSH6* | 1.5-1.9 | |||

| NEIL1* | 2.9 | |||

| OGG1* | 2.0 | |||

| PCNA* | 2.5 | |||

| POL θ* | 2.1-2.6 | |||

| RAD50* | 1.4 | |||

| RAD51* | 4.2-6.5 | |||

| UNG* | 1.8 | |||

| UNG2 | 1.7 | |||

| XRCC4* | 1.0-5.2 | |||

| Tonsil IgD−CD38++ cells | ||||

| AICDA* | 15.4 | CR2* | 1.7 | POL ζ (Rev3) |

| CD38* | 8.8 | ERCC1* | 1.5 | XPA |

| CD80 (B7-1)* | 1.8 | MSH4* | 1.5 | XPC |

| EXO1* | 6.4 | POL ι | 1.5 | XPD |

| FEN1* | 2.8-3.5 | POL μ | 3.3 | KU70 (XRCC6) |

| MLH1* | 1.8 | POL η | 2.7 | KU80 (XRCC5) |

| MME (CD10)* | 35-44 | LIG4 | ||

| MSH2* | 2.1 | |||

| PCNA* | 3.7 | |||

| POL θ* | 1.6-3.7 | |||

| RAD51* | 6.2-11.9 | |||

| RPA* | 1.8 | |||

| TNFRSF7 (CD27)* | 3.1 | |||

| UNG* | 3.0 |

Tonsil populations were determined from 3 individual normal donors.

Significant (P < .05) differences between tonsillar naive B cells (CD38−IgD+) versus activated naive/pre-GC founder cells (CD38++IgD+) or tonsillar GC cells (CD38++IgD−).

Initially a list of 170 genes known to contribute to mismatch repair (MMR), base excision repair (BER), nucleotide excision repair (NER), TLS, DNA repair, recombination, switching, and nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ), transcription, and DNA replication were investigated (Table S4). Among the genes examined, AICDA, RPA, EXO1, MSH2, MSH6, PCNA, POLH, and UNG were expressed at increased levels in tonsillar pre-GC (CD19+CD38++IgD+) or GC (CD19+CD38++IgD−) cells or both compared with tonsil naive B cells (CD19+CD38−IgD+), similar to what has been noted by others.62 Although UNG and OGG1 glycosylases were increased in normal GC B cells, single-strand-selective monofunctional UNG1 (SMUG1) was not increased in normal GC B cells. Genes involved in NER (XPA, XPC, XPD, ERCC1, and ERCC4) and NHEJ (KU70, KU80, and LIGASE4) were also not increased, but XRCC4 was significantly increased in pre-GC B cells. Although expression of RAD50 and RAD51 were up-regulated, other genes involved in homologous recombination, radiation sensitivity, and double strand breaks did not change. Although multiple polymerases expressed in B cells have been investigated to determine whether they contribute to SHM, only POLH expression was increased (2- to 4-fold) in tonsillar GC cells compared with tonsil naive B cells. Notably, in vitro stimulation of PB and splenic B cells with recombinant CD154 did not consistently alter expression of genes potentially involved in SHM (data not shown). These patterns of gene expression in tonsillar subsets were confirmed when a separate set of microarray data were acquired from 3 additional tonsil samples from NDs (Figure S4).

Discussion

The current mutation analysis of individual B cells from patients with X-HIgM has enabled a comparison with the mutation patterns in normals and characterization of the molecular mechanisms of SHM operating in the absence of CD40-CD154 interactions. The significantly lower mutation frequency accompanied by few CD27+ memory B cells was sustained into adulthood in patients with X-HIgM, confirming that the mutation defect resulting from the lack of CD40 signals is persistent and that CD40-CD154 interaction is an important step for both generation of memory cells and mutation amplification. Other defects found in X-HIgM included negligible class-switching, as noted previously,63 and a much lower than normal frequency of CD27+ B cells.8 The current data show that CD40-CD154 signals had a greater effect on switching than on the frequency of CD27+ B cells, although the persistent defect in both was notable, suggesting there is a hierarchical dependence on CD40 signals. Although CD27, a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor family member, is noted as a memory B-cell marker in humans,64 less than 14% of the X-HIgM CD27+ B cells were mutated. These data suggest that, in this circumstance, CD27 did not correlate with memory, as previously noted in AICDA-deficient B cells.65 Importantly, the pattern of mutations in X-HIgM B cells is significantly different from that noted in normal CD27+ memory B cells with no targeting of G in RGYW and significantly fewer transversions. The data are most consistent with the conclusion that X-HIgM B cells have experienced a diminished effect of AICDA and UNG, presumably because they have not been exposed to GC reactions. The significantly different mutation frequencies and patterns in X-HIgM B cells versus normal CD27+ IgD+ preswitch or CD27+IgD− postswitch memory B cells provides no support for the contention that the mutated X-HIgM B cells represent either of the normal memory B-cell subsets as previously proposed.7 Rather, these cells appear to be a population of pre-GC B cells that have experienced limited AICDA and UNG activity, presumably because they have not been exposed to GC reactions.

However, mutations clearly occurred in X-HIgM, with some features of normal SHM, including mutational targeting in WRCY and WA motifs, and, therefore, supported previous findings that not all mutation is solely dependent on CD40-CD154 stimulation and GC reactions.5,6 In this regard, it is known that mutations occur in the shark and frog that lack GCs66 and GCs are not required for mutational targeting of RGYW/WRCY motifs in response to immunization in the lymphotoxin α knockout mouse that lack GCs.67 These findings are consistent with the conclusion that, in humans, SHM may be initiated before a GC reaction when the B cell encounters antigen and antigen-activated T cells. However, the data also clearly show that most mutational activity or the survival of memory B cells with heavily mutated VH genes requires CD40-CD154 signals68 or GC reactions. In this regard, GC B cells exhibit increased expression of aicda, as previously shown,69 as well as ung and selected DNA repair genes to achieve diversity and high-frequency mutation.

One of the most striking features of the X-HIgM mutation pattern was the absence of G mutations in RGYW motifs. An important consequence of the loss of RGYW mutations was the decrease of R substitutions. This defect was most likely the consequence of 5- to 15-fold lower aicda expression in naive B cells compared with pre-GC and GC cells because a relation between the level of expression of aicda and SHM has been reported.70 However, aicda expression was apparently sufficient to initiate a pattern of mutations that provided insight into the basic mechanisms of SHM.

A second major abnormality in X-HIgM B cells was a marked decrease in transversions that presumably reflected decreased expression or availability or both of UNG2, another gene up-regulated in GC B cells. A similar skewing toward transitions was attributed to the absence of UNG in a chicken cell line,71 mouse29 and human B cells,72 suggesting that UNG2 is less active in X-HIgM B cells and can explain the relatively increased frequency of transitions in X-HIgM. With the unavailability of UNG2 in X-HIgM, the AICDA-induced lesions were apparently copied over by a high-fidelity polymerase, such as POL δ,39 that inserted thymidine in place of uracil during DNA synthesis generating C→T transitions. In the absence of UNG, SMUG1 can remove uracils from DNA; therefore, SMUG1 is capable of partially complementing UNG2 in UNG-deficient human cells in vitro73 but not in human B-cell lines.74 These findings, along with our gene expression profiling that found down-regulation of SMUG1 in GC cells, as previously noted in murine B cells,75 are consistent with the conclusion that UNG is the major mechanism by which uracil is removed from DNA in human B cells and that the predominance of transitions in X-HIgM B cells relates to the relative insufficiency of UNG in the absence of GC reactions.

AICDA is known to target both strands of DNA27-29,76 ; thus, we concluded that the prominent targeting of C mutations in WRCY motifs, which probably occurs as a direct deoxycytidine attack by AICDA on the transcribed strand, was an indication that AICDA was active in X-HIgM B cells. Although the overall mutation frequency in X-HIgM was considerably less than normal, it is notable that the frequency of C mutations in WRCY was nearly normal, implying that this specific mutational targeting did not depend on CD40-CD154 interactions or GC reactions. Importantly, these mutations are completely absent in subjects who lack expression of AICDA.77 It was of particular interest to note that, although the percentage of all mutations that accumulated in RGYW motifs in X-HIgM was nearly comparable to that found in normal B cells, there were no preferential mutations in the most frequently mutated G position (RGYW). It was possible that decreased G mutations in RGYW might represent not only decreased AICDA activity but also frequent repair of these AICDA-induced mutations. The mechanism responsible for repair of these mutations most likely involves mismatch repair enzymes associated with SHM,39 at least some of which, such as MSH2/MSH6 and EXO1, might be available in B cells in the absence of GC reactions.

Even though the hypermutable G in RGYW was not mutated, the percentage of mutations in RGYW motifs in X-HIgM was nearly normal, implying that mutations must have occurred in the other 3 positions (R_YW). The first and last nucleotides of RGYW motifs are frequently A residues that coincide with WA motifs, and these A residues contributed to the mutations in RGYW in X-HIgM. Assuming that WA mutations result from the activity of POL η,60 this mechanism is the most likely source of these mutations. Thus, the current data suggest that in X-HIgM there is preferential targeting of POL η to RGYW motifs, presumably because of the activity of AICDA. Even though the initial AICDA lesion is apparently repaired, the sequences retain the fingerprint of POL η activity in RGYW sequences. A similar fingerprint could be seen in RGYW motifs in NDs, implying that preferential targeting of POL η to RGYW motifs was a general feature of SHM independent of GC reactions. It is notable that induction of A mutations has recently been shown when a single C is introduced into the nontranscribed strand of a transgenic SHM substrate by recruiting mismatch repair that presumably includes POL η76 and establishes a linkage between AICDA and POL η activities.

The presence of WA mutations in X-HIgM B cells suggested that POL η is active in the absence of GC reactions. However, the frequency of POL η–related mutations was much greater in normal B cells, even though expression of pol η was not increased in GC cells. It was recently noted that some POL η activity might require the activity of MSH2.33 Of note, MSH2 was up-regulated 1.6- to 2.1-fold in GC cells. Thus, the apparent increased activity of POL η in normal B cells may relate to the up-regulation of MSH2 and its capacity to recruit POL η to the site of mutation. This conclusion is consistent with the recent observation that the discrepancy in the induction of A mutations when a C is introduced in the transcribed strand is overcome when MSH2 is absent76 and is compatible with a role for MSH2 in recruitment of POL η to the targeted motifs during SHM.

In summary, the X-HIgM B-cell repertoire has few CD27+ memory B cells, and the quantity and pattern of mutation suggest a low level of AICDA activity initiates SHM, but a GC reaction is required for amplification and up-regulation of genes that are required for the full spectrum of mutation.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients, their families, and NDs for their participation in this study and Shuying Liu, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, for providing patient blood samples. We thank Randy Fischer for sample preparation for the microarray studies; Colleen Satorius for the normal donor IgD and CD27 subset sequencing; and Liusheng He, Doug Olson, and Jim Simone for cell sorting.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases intramural research program. S.S.D. was supported by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: N.S.L., P.L.L., A.C.G., and P.E.L. designed the research protocol; N.S.L., S.Y., and P.H.L.K. prepared the sequence data; D.E.R. performed statistical analyses; W.Z. performed the CD154 in vitro stimulation; P.L.L., D.D.J., and S.S.D. performed the microarray analysis; N.S.L. did the mutation analysis and wrote the manuscript; and N.S.L. and P.E.L. contributed to the final preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Peter E. Lipsky, Autoimmunity Branch, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, 9000 Rockville Pike, Bldg 10, Rm 6D47C, Bethesda, MD 20892-1560; e-mail: peterlipsky@comcast.net.