Abstract

Thymocytes and thymic epithelial cell (TEC) cross-talk is crucial to preserve thymic architecture and function, including maturation of TECs and dendritic cells, and induction of mechanisms of central tolerance. We have analyzed thymic maturation and organization in 9 infants with various genetic defects leading to complete or partial block in T-cell development. Profound abnormalities of TEC differentiation (with lack of AIRE expression) and severe reduction of thymic dendritic cells were identified in patients with T-negative severe combined immunodeficiency, reticular dysgenesis, and Omenn syndrome. The latter also showed virtual absence of thymic Foxp3+ T cells. In contrast, an IL2RG-R222C hypomorphic mutation permissive for T-cell development allowed for TEC maturation, AIRE expression, and Foxp3+ T cells. Our data provide evidence that severe defects of thymopoiesis impinge on TEC homeostasis and may affect deletional and nondeletional mechanisms of central tolerance, thus favoring immune dysreactive manifestations, as in Omenn syndrome.

Introduction

Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) comprises a heterogeneous group of genetic disorders that affect early stages in T-cell development resulting in the virtual lack of circulating T lymphocytes and, depending on the nature of the genetic defect, in B and/or NK lymphocyte depletion.1 In contrast, hypomorphic mutations in these genes may result in a more complex phenotype, with residual development of T lymphocytes. Oligoclonal expansion of T lymphocytes that infiltrate peripheral tissues is typically observed in Omenn syndrome and is associated with significant tissue damage.2 Although Omenn syndrome is often the result of hypomorphic mutations in RAG1 and RAG2 genes,3 mutations in other genes that control early stages in T-cell development have also been identified, suggesting a common pathophysiologic mechanism.4 Our previous studies in RAG-mutated patients5 and mice6 indicate that impairment of deletional and nondeletional mechanisms of central tolerance may play a key role in the pathophysiology of Omenn syndrome

Studies in mice indicate that signals delivered by thymocytes are crucial to induce maturation of cortical and medullary thymic epithelial cells (cTECs, mTECs) from a common precursor and to support maintenance of thymic architecture.7-11 A subset of mature mTECs and thymic dendritic cells (DCs) express Aire, a transcription factor driving the expression of tissue-restricted antigens12 that are presented to autoreactive T cells, hereby inducing deletional central tolerance.13 In addition, interaction between epithelial cells of Hassall corpuscles and thymic DCs has been implicated to mediate differentiation of T-cell precursors into Foxp3+ cells that include natural regulatory T cells (nTregs).14

We have hypothesized that genetic defects that abrogate or severely affect early stages of T-cell development in humans may result in profound abnormalities in the distribution and function of TECs and thymic DCs and may affect induction of the mechanisms of central tolerance, thus providing a basis for the genetic heterogeneity of Omenn syndrome. To test this hypothesis, we have performed a detailed analysis of thymic architecture and maturation in 9 patients representative of 6 different genetic defects that variably affect early stages of T-cell development.

Methods

Patients and thymic biopsies

Clinical, immunologic, and molecular features of the patients studied are listed in Table 1. Thymic biopsies from patients P3, P4, P6, P7, and P9 were obtained before hematopoietic cell transplantation in 5 patients, in agreement with protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board, Hospital for Sick Children (Toronto, ON) with informed consent obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Thymic samples from patients P1, P2, P5, and P8 were retrieved during postmortem examination. Anonymous normal thymi were obtained from infants with no immunologic abnormalities who underwent elective surgery for cardiovascular defects correction, according to the protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board, Spedali Civili (Brescia, Italy), and Department of Paediatric Immunology, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals Foundation Trust (Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom).

Clinical, immunologic, and genetic features of the patients

| Patient no. . | Age at biopsy, mo . | ALC, cells/μL . | CD3+, cells/μL . | CD4+, cells/μL . | CD8+, cells/μL . | CD19+, cells/μL . | CD16+/CD56+, cells/μL . | Clinical features . | Mutation . | Diagnosis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 10*† | 400 | < 1% | < 1% | < 1% | < 1% | < 1% | Pancytopenia, IUGR | AK2: c.400–401delCT/c. 614–615delGG | RD |

| P2 | 7.5* | 729 | 114 | 0 | 40 | 721 | 16 | PCP | IL2RG: IVS3+1G>C | SCIDX1 |

| P3 | 2 | 860 | 35 | 13 | 21 | 750 | 9 | Pneumonia, FTT | IL2RG: R258Q | SCIDX1 |

| P4 | 10 | 2500 | 1600 | 1000 | 475 | 475 | 225 | PCP | IL2RG: R222C | SCIDX1 |

| P5 | 2* | 323 | 45 | 6 | 39 | 26 | 13 | Disseminated candidiasis | Unknown | ADA-SCID‡ |

| P6 | 2 | 1090 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 676 | 391 | Positive family history | CD3δ: R68X/R68X | CD3δ-SCID |

| P7 | 3 | 900 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 280 | Positive family history | RAG2: g.4953delT/4953delT | T-B- SCID |

| P8 | 3* | 8600 | 3698 | 946 | 1462 | NA | 3956 | ED, CD, FTT, myocarditis, IP | RAG2: R229Q/R229Q | OS |

| P9 | 6.5 | 4591 | 2670 | 1669 | 125 | 1437 | 924 | ED, FTT, CD, bronchiolitis, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly | RMRP: allele 1: ins ACTCTGTGAATACTCT GTGAAGCTGA at −10 allele 2: C4T | OS |

| Patient no. . | Age at biopsy, mo . | ALC, cells/μL . | CD3+, cells/μL . | CD4+, cells/μL . | CD8+, cells/μL . | CD19+, cells/μL . | CD16+/CD56+, cells/μL . | Clinical features . | Mutation . | Diagnosis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 10*† | 400 | < 1% | < 1% | < 1% | < 1% | < 1% | Pancytopenia, IUGR | AK2: c.400–401delCT/c. 614–615delGG | RD |

| P2 | 7.5* | 729 | 114 | 0 | 40 | 721 | 16 | PCP | IL2RG: IVS3+1G>C | SCIDX1 |

| P3 | 2 | 860 | 35 | 13 | 21 | 750 | 9 | Pneumonia, FTT | IL2RG: R258Q | SCIDX1 |

| P4 | 10 | 2500 | 1600 | 1000 | 475 | 475 | 225 | PCP | IL2RG: R222C | SCIDX1 |

| P5 | 2* | 323 | 45 | 6 | 39 | 26 | 13 | Disseminated candidiasis | Unknown | ADA-SCID‡ |

| P6 | 2 | 1090 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 676 | 391 | Positive family history | CD3δ: R68X/R68X | CD3δ-SCID |

| P7 | 3 | 900 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 280 | Positive family history | RAG2: g.4953delT/4953delT | T-B- SCID |

| P8 | 3* | 8600 | 3698 | 946 | 1462 | NA | 3956 | ED, CD, FTT, myocarditis, IP | RAG2: R229Q/R229Q | OS |

| P9 | 6.5 | 4591 | 2670 | 1669 | 125 | 1437 | 924 | ED, FTT, CD, bronchiolitis, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly | RMRP: allele 1: ins ACTCTGTGAATACTCT GTGAAGCTGA at −10 allele 2: C4T | OS |

NA indicates not available; IUGR, intrauterine growth retardation; PCP, Pneumocystis pneumonia; FTT, failure to thrive; ED, erythroderma; CD, chronic diarrhea; IP, interstitial pneumonia; RD, reticular dysgenesis; SCID, severe, combined immunodeficiency; ADA, adenosine deaminase; OS, Omenn syndrome; and RMRP, ribonuclease mitochondrial RNA-processing mutation.

Postmortem examination.

Died of disseminated adenovirus infection after T-cell-depleted haploidentical hematopoietic cell transplantation.

Diagnosis of ADA deficiency was established based on lack of ADA activity in red blood cells.

Histologic and immunohistochemical procedures

Formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded thymic sections have been used for routine hematoxylin and eosin and single/double immunohistochemical staining using the following reagents: claudin-4 (Cld4), Ulex Europaeus Agglutinin-1 (UEA-1) ligand, and Aire as markers of TEC maturation; S-100, CD208/DCLAMP, CD11c, and CD303/BDCA2 as markers of DCs; CD163 to identify CD11c+ macrophages; and Foxp3 as a marker of nTreg. Double immunofluorescence staining for cytokeratin 5 (CK5) and cytokeratin 8 (CK8) have been used to evaluate TEC maturation and distribution. Detailed information is available in supplemental data (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Slides were viewed with an Olympus Bx60 microscope using U Plan Apochromats 10×, 20×, and 40× lenses. Images were acquired using a DP70 model camera (Olympus) and were processed with CellF imaging software (Soft Imaging System GmbH) and Adobe photoshop version 7.0 (Adobe Systems). Aire+ cells, when present, have been counted on 10 different high power fields for each section and values expressed as number of cells/mm2 plus or minus SD.

Results and discussion

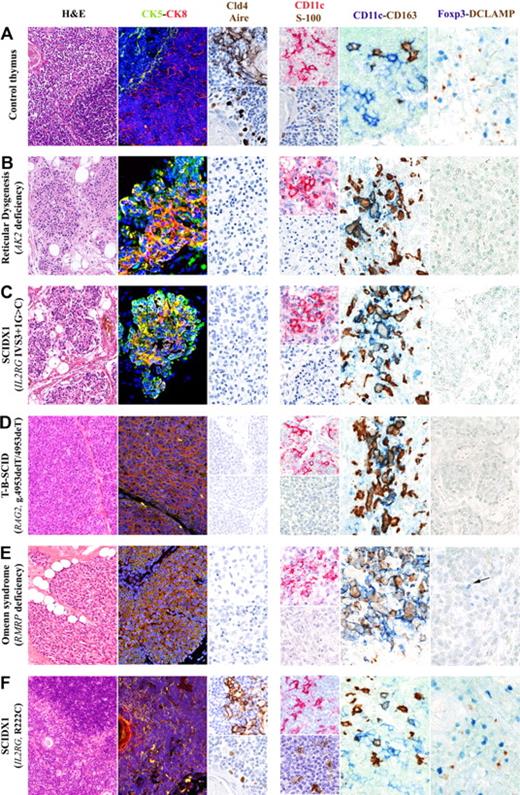

As shown in Figure 1 and supplemental Figure 1, thymic sections from patients with null mutations in the AK2 gene (reticular dysgenesis, patient P1), IL2RG (patients P2 and P3), CD3D (patient P6), or RAG2 (patient P7) genes, or with complete lack of adenosine deaminase activity (patient P5), showed severe atrophy, loss of corticomedullary demarcation (CMD), and lobular architecture with thin septa. Similar findings, with loss of CMD and lack of Hassall corpuscles, were also observed in patients P8 and P9, with Omenn syndrome resulting from hypomorphic mutations in RAG2 and RMRP, respectively. Both of these patients had a markedly reduced number of CD3+ T cells, as previously reported.2,15 In contrast, biopsies from patient P4 (whose hypomorphic R222C mutation in the IL2RG gene was permissive for normal thymopoiesis16 ) showed preserved thymic architecture.

Thymic compartmentalization and maturation of mTECs, DCs, and nTregs is abrogated in patients with severe defects in T-cell development but is preserved in a patient whose genetic defects are largely permissive for T-cell development. Detailed analysis of the thymic biopsy from a representative normal thymus (A) shows defined CMD (hematoxylin and eosin staining) with normal compartmentalization of CK8+CK5− cTECs (CK8, red staining) and CK8−CK5+ mTECs (CK5, green staining). Mature mTECs express Cld4 and Aire (brown staining, top and bottom images, respectively). In contrast, mutations that abrogate T-cell development (reticular dysgenesis, B; γc-null SCIDX1, C; RAG2-null T−B−SCID, D) or that are only partially permissive for T-cell development (Omenn syndrome associated with RMRP mutations, E), are associated with profound atrophy and loss of CMD (hematoxylin and eosin staining), highlighted by the presence of a diffuse epithelial network mostly composed of CK5 and CK8 double-positive immature TECs (yellow staining). No expression of claudin-4 (Cld4) and Aire was detected in these samples. In contrast, as shown in panel F, the biopsy from the patient carrying a hypomorphic R222C mutation in the IL2RG gene, permissive for T-cell development, shows normal thymic architecture with CMD (hematoxylin and eosin staining), normal distribution of CK8+CK5− cTECs (CK8, red) and CK8−CK5+ mTECs (CK5, green), and expression of Cld4 and Aire (brown staining, top and bottom images, respectively). In the normal thymus (A), CD11c+ (top image, red staining) and S-100+ (bottom image, brown staining) DCs are distributed in the medullary areas. Combined CD11c and CD163 staining differentially marks CD11c+ DCs in the medullary region and CD163+ macrophages, which are primarily distributed into the cortex, with only rare CD11c and CD163 double-positive cells. Conversely, severe depletion of DCs is present in the thymic biopsies of all patients whose genetic defects severely compromise T-cell development. (B-E) Absence of S-100+ cells in all patients. In addition, CD11c+cells, although present in good number, largely coexpress CD163, indicating a macrophage phenotype. Rare CD11c+CD163− DCs have been observed in the patient with Omenn syndrome (E). In the control thymus, Foxp3+ nTreg clusters around mature activated CD208+ (DC-LAMP) DCs, as highlighted by double-staining procedures (A). In contrast, thymic biopsies from patients with genetic defects that are nonpermissive for T-cell development show absence of mature activated CD208+ (DC-LAMP) DCs and Foxp3+ nTregs (B-D). The thymic biopsy from the Omenn syndrome patient (E) shows absence of CD208+ (DC-LAMP) DCs but focal expression of rare Foxp3+ cells (E). In contrast, the thymus from the patient with hypomorphic R222C mutation in the IL2RG gene demonstrates normal distribution of both S-100+ and CD11c+ DCs (F, CD11c+ top image, red staining; S-100+ bottom image, brown staining) along with the evidence of Foxp3+ nTreg interacting with mature activated CD208+ (DC-LAMP) DCs (F). Hematoxylin and eosin staining, original magnification ×10; immunofluorescence stainings, original magnification ×20: CK5 (green), CK8 (red), nuclei (blue), merge (yellow). Single immunohistochemical stainings, original magnification ×40: Cld4, Aire, S-100 (brown) and CD11c (red); double immunohistochemical stainings, original magnification ×40: CD11c (blue) and CD163 (brown); Foxp3 (blue) and DCLAMP (CD208; brown).

Thymic compartmentalization and maturation of mTECs, DCs, and nTregs is abrogated in patients with severe defects in T-cell development but is preserved in a patient whose genetic defects are largely permissive for T-cell development. Detailed analysis of the thymic biopsy from a representative normal thymus (A) shows defined CMD (hematoxylin and eosin staining) with normal compartmentalization of CK8+CK5− cTECs (CK8, red staining) and CK8−CK5+ mTECs (CK5, green staining). Mature mTECs express Cld4 and Aire (brown staining, top and bottom images, respectively). In contrast, mutations that abrogate T-cell development (reticular dysgenesis, B; γc-null SCIDX1, C; RAG2-null T−B−SCID, D) or that are only partially permissive for T-cell development (Omenn syndrome associated with RMRP mutations, E), are associated with profound atrophy and loss of CMD (hematoxylin and eosin staining), highlighted by the presence of a diffuse epithelial network mostly composed of CK5 and CK8 double-positive immature TECs (yellow staining). No expression of claudin-4 (Cld4) and Aire was detected in these samples. In contrast, as shown in panel F, the biopsy from the patient carrying a hypomorphic R222C mutation in the IL2RG gene, permissive for T-cell development, shows normal thymic architecture with CMD (hematoxylin and eosin staining), normal distribution of CK8+CK5− cTECs (CK8, red) and CK8−CK5+ mTECs (CK5, green), and expression of Cld4 and Aire (brown staining, top and bottom images, respectively). In the normal thymus (A), CD11c+ (top image, red staining) and S-100+ (bottom image, brown staining) DCs are distributed in the medullary areas. Combined CD11c and CD163 staining differentially marks CD11c+ DCs in the medullary region and CD163+ macrophages, which are primarily distributed into the cortex, with only rare CD11c and CD163 double-positive cells. Conversely, severe depletion of DCs is present in the thymic biopsies of all patients whose genetic defects severely compromise T-cell development. (B-E) Absence of S-100+ cells in all patients. In addition, CD11c+cells, although present in good number, largely coexpress CD163, indicating a macrophage phenotype. Rare CD11c+CD163− DCs have been observed in the patient with Omenn syndrome (E). In the control thymus, Foxp3+ nTreg clusters around mature activated CD208+ (DC-LAMP) DCs, as highlighted by double-staining procedures (A). In contrast, thymic biopsies from patients with genetic defects that are nonpermissive for T-cell development show absence of mature activated CD208+ (DC-LAMP) DCs and Foxp3+ nTregs (B-D). The thymic biopsy from the Omenn syndrome patient (E) shows absence of CD208+ (DC-LAMP) DCs but focal expression of rare Foxp3+ cells (E). In contrast, the thymus from the patient with hypomorphic R222C mutation in the IL2RG gene demonstrates normal distribution of both S-100+ and CD11c+ DCs (F, CD11c+ top image, red staining; S-100+ bottom image, brown staining) along with the evidence of Foxp3+ nTreg interacting with mature activated CD208+ (DC-LAMP) DCs (F). Hematoxylin and eosin staining, original magnification ×10; immunofluorescence stainings, original magnification ×20: CK5 (green), CK8 (red), nuclei (blue), merge (yellow). Single immunohistochemical stainings, original magnification ×40: Cld4, Aire, S-100 (brown) and CD11c (red); double immunohistochemical stainings, original magnification ×40: CD11c (blue) and CD163 (brown); Foxp3 (blue) and DCLAMP (CD208; brown).

Development of TECs is marked by differential expression of CK5 and CK8, with TEC progenitors being mostly CK5+CK8+ and mature cTECs and mTECs CK8+CK5− and CK8−CK5+, respectively17 (Figure 1). Thymic biopsies from all patients, with the exception of patient P4, showed a diffuse epithelial network mostly composed of CK5+CK8+ cells, with predominance of CK8 expression. In contrast, normal compartmentalization of CK8+CK5− cTECs and CK8−CK5+ mTECs was detected in patient P4 (Figure 1, supplemental Figure 1).

Maturation of mTECs is marked by expression of Cld4 and UEA-1 binding,18 with a subset of mature Cld4+UEA-1+ mTECs expressing Aire18,19 (Figure 1). With the exception of patient P4, thymic sections from all other patients in our series showed virtual absence of Cld4+UEA-1+ mTECs and lack of Aire expression, regardless of the genetic defect (Figure 1, supplemental Figure 1). In contrast, preserved UEA-1 binding (data not shown) and normal Cld4 and Aire expression (supplemental Figure 1) were observed in the thymus from patient P4, with no significant difference in the number of Aire+ mTECs compared with control thymus (392.2 ± 94.5 vs 414 ± 106.2 cells/mm2).

Staining for S-100, CD11c (Figure 1, supplemental Figure 1), and CD303/BDCA2 (data not shown), covering the large majority of DCs populations,showed virtual absence of thymic DCs in all patients with the exception of patient P4. Although a significant number of CD11c+ cells was detected in all patients, these cells largely coexpressed CD163 and, hence, represented macrophages (Figure 1, supplemental Figure 1). The presence of CD163+ and CD11c+CD163+ macrophages in patient P1 (Figure 1) is in keeping with the notion that the myeloid differentiation arrest in reticular dysgenesis affects the granulocytic but not the monocytic lineage. Overall, these data extend previous observations that the number of thymic DCs is markedly decreased in patients with X-linked SCID.20

Thymic DCs have been implied to mediate a critical role in the conversion of autoreactive T cells into nTregs.14 Staining of control thymi confirmed that Foxp3+ cells were distributed around mature/activated (CD208/DCLAMP+) DCs (Figure 1). No (patient P8) or very rare (patient P9) Foxp3+ cells were observed in thymic biopsies from patients with Omenn syndrome (Figure 1, supplemental Figure 1), despite the residual ability to generate T cells. In contrast, a normal number of Foxp3+ cells were present in patient P4, carrying the hypomorphic IL2RG R222C mutation that was permissive to T-cell development (Figure 1). To our knowledge, this is the first study in which thymic architecture and maturation of thymic stromal cells have been analyzed in detail in patients with a variety of defects that affect early stages in T-cell development. The lack of Aire expression and the severe depletion of thymic Foxp3+ cells may provide a unifying mechanism for the pathophysiology of Omenn syndrome in patients whose genetic defects severely reduce, but do not completely abrogate, T-cell development.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Network Operativo per la Biomedicina di Eccellenza in Lombardia (F.F., A.V., L.D.N.), Fondazione CARIPLO (P.L.P., A.V.), and Italian Telethon Foundation (A.V.).

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH, Bethesda, MD; grant P01AI076210) and by the Manton Foundation.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: P.L.P. performed the study and participated in critical interpretation of the findings and in writing the manuscript; F.F. participated in critical interpretation of the findings and in research design; M.R. performed some of the experiments; A.R.G. provided biologic specimens and participated in writing the manuscript; A.V. participated in writing and in critical interpretation of the findings; C.M.R. provided most of the thymic samples and participated in critical interpretation of the findings; and L.D.N. designed the study and participated in critical interpretation of the findings and in writing.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Luigi D. Notarangelo, Division of Immunology, Children's Hospital Boston, Karp Family Bldg, 9th Fl, Rm 9210, 1 Blackfan Cir, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail: luigi.notarangelo@childrens.harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

*C.M.R. and L.D.N. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal