Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection can modify the cytokine expression profiles of host cells and determine the fate of those cells. Of note, expression of interleukin-13 (IL-13) may be detected in EBV-associated Hodgkin lymphoma and the natural killer (NK) cells of chronic active EBV-infected patients, but its biologic role and regulatory mechanisms are not understood. Using cytokine antibody arrays, we found that IL-13 production is induced in B cells early during EBV infection. Furthermore, the EBV lytic protein, Zta (also known as the BZLF-1 product), which is a transcriptional activator, was found to induce IL-13 expression following transfection. Mechanistically, induction of IL-13 expression by Zta is mediated directly through its binding to the IL-13 promoter, via a consensus AP-1 binding site. Blockade of IL-13 by antibody neutralization showed that IL-13 is required at an early stage of EBV-induced proliferation and for long-term maintenance of the growth of EBV immortalized lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs). Thus, Zta-induced IL-13 production facilitates B-cell proliferation and may contribute to the pathogenesis of EBV-associated lymphoproliferative disorders, such as posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD) and Hodgkin lymphoma.

Introduction

Cytokines act as a double-edged sword in many viral infections. For the host, cytokines play a central role in communicating, initiating, activating, and balancing immune system. On the other hand, viruses use various strategies to manipulate host cytokine production in favor of virus survival, replication, and infection.1 Mechanistically, most viruses alter the host's cytokine expression profiles by influencing the amounts or function of 2 key cytokine transcriptional activators, nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and activating protein-1 (AP-1).1 This common regulatory mechanism is seen in Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), influenza virus, and human T-cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV-1) infections.1 Virus-induced cytokine production provides a growth advantage for virus-infected cells and also may modulate host immune responses, potentially resulting in the development of persistent infection, immunopathologic effects, or tumorigenesis.1

EBV is an oncogenic γ-herpes virus that persistently infects over 95% of the human population.2,3 The life cycle of EBV includes latent and lytic stages. Primary EBV infection usually is asymptomatic, but the virus is the main causative agent of infectious mononucleosis in young adults. EBV is a lymphotropic virus associated with diverse forms of lymphoma, including Burkitt lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, and natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma.4 EBV infection also is strongly associated with the pathogenesis of other diseases, such as nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), gastric carcinoma, and multiple sclerosis.4,5 The incidence of B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders resulting from EBV infection is increased in organ transplanted patients treated with immunosuppressive drugs, in individuals with underlying immunodeficiency, and in rheumatoid arthritis patients prescribed methotrexate and related drugs.6,7 In vitro, primary B cells infected with EBV may be transformed into lymphoblastoid cell lines,4 which are characterized by unlimited proliferation. Thus, the ability of EBV to induce cell proliferation, immortalization, and transformation likely involves the modification of factors in the host cells by viral latent and lytic gene products, encoded by the large, 172-kb viral DNA genome.4

As an oncogenic virus, EBV uses various strategies to modify cellular gene expression so that EBV-infected host cells can proliferate indefinitely. One group of targets is the cytokine family. In addition to the viral (BCRF-1) product viral IL-10 (vIL-10) being an interleukin-10 (IL-10) homolog,4 many other proteins encoded by EBV have been shown to be able to regulate cytokine expression in various ways. First, the viral products can up-regulate cytokine expression by triggering the regular protein kinase C (PKC) pathway, the interaction between EBV gp350 and CD21 being the best example.8,9 Second, the up-regulation of cytokine expression may be stimulated by viral transcriptional factors binding to the cytokine promoters. LMP1, a viral latent membrane protein that constitutively activates CD40 signaling, is well known for using its downstream signaling to activate the expression of IL-6 and IL-10.10,11 Third, an EBV-encoded small RNA, EBER, induces expression of IL-10 via retinoic acid-inducible gene (RIG)–mediated interferon regulatory factor-3 (IRF-3) signaling.12 Fourth, EBV nuclear antigen 2 (EBNA2) may activate interferon-β (IFN-β) expression through its interaction with Jκ recombination signal sequence binding protein (RBP-Jκ).13 Fifth, an EBV lytic transactivator, Zta, can transactivate the expression of IL-8 and IL-10 by binding directly to their promoters.14,15 Notably, both IL-6 and IL-10 can act as autocrine growth factors for B-cell proliferation,16,17 suggesting the importance of these virus-induced cytokines in EBV-mediated oncogenesis. In addition to these cytokines, expression of IL-13 has been documented specifically in EBV-associated Hodgkin lymphoma and the NK cells of chronic active EBV-infected patients.18,19 However, the biologic roles and molecular mechanisms of regulation of IL-13 induction in EBV-related diseases remain obscure.

IL-13 is produced predominantly by Th2 cells, NK cells, B cells, and mast cells, and regulates an array of biologic functions in a variety of cell types.20 Functionally, IL-13 is able to promote proliferation and differentiation of B cells, to enhance class switching of immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) and IgE in B cells, to up-regulate CD23 and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II protein expression by monocytes and B cells, and to inhibit production of inflammatory cytokines by macrophages.20 IL-13 also acts a potent inducer of asthma and tissue fibrosis.20 Furthermore, IL-13 can enhance tumor cell growth and has been considered as an antitumor target in Hodgkin lymphoma.21

In this study, to elucidate the roles of cytokines in EBV infection, we analyzed systematically the production of cytokines following infection with EBV using cytokine antibody arrays. Of note, IL-13 is produced predominantly in EBV-infected B cells. In addition, we show that the EBV lytic gene product, Zta, is the major inducer of IL-13 production. Mechanistically, Zta can transactivate the expression of IL-13 by binding directly to a putative AP-1 site present in the IL-13 promoter. Impressively, IL-13 antibody blockade indicated that IL-13 can serve as a growth factor for EBV-infected B cells or EBV-immortalized lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs), suggesting that Zta-induced IL-13 expression might play an important role in EBV-associated lymphoproliferative diseases.

Methods

EBV virion preparation, cell purification, and EBV infection

EBV-harboring B95.8 cells were seeded at a density of 106 cells/mL and then treated with 40 ng/mL tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate and 3 mM sodium butyrate. After 3 days, viruses were harvested, concentrated, resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium, and then stored at −80°C. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from the whole blood of anonymous donors (from Taipei Blood Center of Taiwan Blood Service Foundation) by Ficoll-paque density gradient centrifugation (Amersham Biosciences). CD19-positive B cells were purified from PBMCs using Dynabeads (Dynal) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Purified PBMCs or B cells were seeded at a density of 106 cells/mL and then infected with the EBV stock, diluted 1:100.

Cell lines and antibodies

Akata and BJAB cells are derived from Burkitt lymphoma, and Akata EBV-positive cells are the EBV-negative Akata cells infected with recombinant EBV.22 L428 cells are derived from Hodgkin lymphoma. LCLs were established by EBV infection of PBMCs, CD19-positive B cells, and tonsil mononuclear cells in vitro. All B-cell lines were cultured in complete RPMI medium (containing 10% fetal calf serum [FCS], 1 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin). HEK293T cells were maintained in complete Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM; containing 10% FCS, 1 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin). Antibodies against β-actin (clone: AC-15; Sigma-Aldrich), glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; clone: 6C5; Biodesign), and human IgG (ICN Biomedical) also were used. Antibodies against Zta (clones: 1B4 and 4F10), Rta (clone: 467), EBNA1 (patient's serum: NPC47), and LMP1 (clone: S12) were as reported previously.23

RNA extraction and RT-Q-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from EBV-infected or EBV-uninfected B cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription (RT) and quantitative (Q) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) have been described previously.24 IL-13 and GAPDH mRNAs were detected using the TaqMan primer/probe sets (Pre-Developed Assay Reagents; Applied Biosystems). Primers and probes for EB viral transcripts were as follows: EBNA1: forward primer 5′-TCATCATCATCCGGGTCTCC-3′, reverse primer 5′-CCTACAGGGTGGAAAAATGGC-3′, probe 5′-(FAM)CGCAGGCCCCCTCCAGGTAGAA(TAMRA)-3′; EBNA2: forward primer 5′-TCAATGCACCCTCTTACTCATCA-3′, reverse primer 5′-GGGACCGTGGTTCTGGACTAT-3′, probe 5′-(FAM) CACCCCAAATGATC(MGB)-3′; Zta: forward primer 5′- AGCAGCCACCTCACGGTAGTG -3′, reverse primer 5′- AATCGGGTGGCTTCCAGAA -3′, probe 5′-(FAM) CAGTTGCTTAAACTTGGCCCGGCA (TAMRA)-3′; Rta: forward primer 5′- CGGCCTGACTGGTTTCTTCA -3′, reverse primer 5′- CAGTAACCCCCGAGGCAAGT -3′, probe 5′-(FAM) CAGGGTCCTCCAACA (MGB)-3′.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed using radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet-P40 [NP40], 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS] with protease inhibitors). Cell lysates were resolved by electrophoresis in SDS-polyacrylamide gels and electrotransferred onto Hybond-C extra membranes (Amersham Biosciences). Milk-blocked blots were incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight and then washed and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) at room temperature for 1 hour. The proteins of interest were revealed using the Western Lightning chemiluminescence reagent (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

Cytokine antibody array and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Supernatants were collected from 106 EBV-infected or uninfected PBMCs on the seventh day after infection, and cytokine expression profiles were determined using RayBio Human Cytokine Antibody Array III (RayBiotech) according to the manufacturer's instructions. IL-13 protein levels were measured in supernatants using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Plasmids

The simian virus 40 promoter-driven EBNA1 (pSG5-EBNA1)– and Rta (pSG5-Rta)–expressing plasmids, and the CMV promoter-driven Zta (pRC-Zta- and EBNA2 (pRC-EBNA2)–expressing plasmids were constructed for our previous studies.24 LMP1- and LMP2A-expressing plasmids (pSG5-LMP1 and pSG5-LMP2A) are gifts from Alan B. Rickinson (Cancer Research UK Institute for Cancer Studies, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom) and Richard Longnecker (Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL). The lentivirus-based Zta-expressing plasmid, pSIN-Zta, was constructed by insertion of a full-length Zta cDNA fragment into pSIN vector at the 5′ NdeI site and the 3′ MluI site. A series of luciferase reporter plasmids driven from IL-13 promoter fragments (nucleotides [nt] −1159 to +65, nt −229 to +65, nt −150 to +65, nt −109 to +65, and nt −96 to +65) were inserted into the pGL2-basic vector (Promega) through the KpnI and NheI sites. To construct the pIL-13 (-109/+65) ZREmt and the pIL-13 (-1159/+65) ZREmt reporter plasmids, the Zta responsive element (ZRE; TGAGTAA) within the IL-13 promoter region −97 to −103 in the reporter plasmids was replaced with AAAATAA by site-directed mutagenesis. The lentivirus-based siZta and siLuciferase expression plasmids were constructed by insertion of siRNA sequences into the pLKO.1 plasmid. The siRNA targeted to the sequences 5′-CAACAGCTAGCAGACATTG-3′ of Zta, and 5′-CCTAAGGTTAAGTCGCCCT-3′ of Luciferase.

Preparation and infection of Zta- and siZta-expressing lentiviruses

The methods for production and infection with lentiviruses were adapted from Godfrey paper with some modifications.25 Briefly, 6 μg p8.91, 3 μg pMD2.G, and 9 μg pSIN-vector, pSIN-Zta, pLKO-siZta, or pLKO-siLuciferase were cotransfected into HEK293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The supernatants containing infectious pSIN-vector or pSIN-Zta lentivirus were collected on day 3 after transfection and stored at −80°C. For lentivirus infection, 106 L428 cells or 2 × 105 LCLs were infected with pSIN-vector or pSIN-Zta lentivirus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 4.

Reporter assay

HEK293T cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well in a 12-well plate and then transfected with the various IL-13 promoter luciferase reporter plasmids (1.2 μg) combined with 0.6 μg pRC-Zta and 0.2 μg green fluorescent protein (GFP)–expressing plasmids (pEGFP-C1, Promega) using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's instructions. On day 3 after transfection, the cells were harvested, and the luciferase activities and GFP fluorescent intensity were detected using the Bright-Glo Luciferase Assay System kit (Promega). The relative fold induction of luciferase activity from each transfectant was normalized to its GFP intensity and pGL2-basic vector control.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

Briefly, 107 L428 cells were infected with pSIN-vector or pSIN-Zta-lentivirus at an MOI of 4. On day 5 after infection, cells were harvested, and then the complex of DNA and Zta was precipitated using an anti-Zta antibody (clone: 1B4). DNA was extracted, precipitated, and then analyzed by PCR with IL-13 promoter primers as follows: forward 5′-TTGCCTGCCGCTGGAATTAAACC-3′ and reverse 5′-AAGCGCCATGAGGCCCAGTGC-3′. The amplification program was 95°C for 45 seconds, 52°C for 45 sseconds, 72°C for 30 seconds, repeated for a total of 35 cycles. For amplification of the GAPDH promoter region, the primers used were as follows: forward 5′-AGCTCAGGCCTCAAGACCTT-3′ and reverse 5′-AAGAAGATGCGGCTGACTGT-3′. The amplification program was 95°C for 45 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for 30 seconds, repeated for a total of 40 cycles.

EMSA

HEK293T cells were cultured at a density of 106 cells in a 10-cm dish. After 24 hours, cells were transfected with 8 μg pRC or pRC-Zta. On day 3 after transfection, cell nuclei were harvested, and electromobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed as described previously.24 In brief, the single-stranded oligonucleotides (ZRE: 5′-ATCAAGATGAGTAAAGATGTG-3′ and ZREmt: 5′-ATCAAGAAAAATAAAGATGTG-3′) and their complementary oligomers were annealed to form a double strand and end-labeled with [γ-32P]-ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs). The binding reaction was carried out in a total volume of 20 μL containing 8 μg nuclear extracts, 62.5 nM 32P-labeled probes, 20 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM ethylenedinitrilotetra acetic acid (EDTA), 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol, and 2 μg poly(dI-dC). For competition EMSA, 2 μM unlabeled ZRE or ZREmt oligonucleotides were added to the reactions. For antibody supershift EMSA, 2 μL anti-Zta or anti-glutathione S transferase (GST) antibodies were added to the reactions. All reactions were incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes and then electrophoresed in 6% native polyacrylamide gels with Tris-borate buffer (90 mM Tris, 90 mM boric acid, 2 mM EDTA). The gels were dried and exposed to X-ray film.

Bisulfite sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from indicated cells, and 1 μg genomic DNA was bisulfite-converted using an EZ DNA Methylation-Gold kit (ZymoResearch, Orange, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. IL-13 promoter sequences from −280 to +58 were amplified by PCR using forward primer 5′-TTGGAATTTAGGGTAGTATTGTAAATGTTA-3′ and reverse primer 5′-TAAAACCCAATACCAACAAAAAAAA-3′. Each amplification cycle consisted of 95°C for 45 seconds, 55°C for 45 seconds, 72°C for 30 seconds, repeated for a total of 40 cycles. PCR products were sequenced directly using the primers previously described.

Treatment of LCLs with 5-azacytidine

L428 cells were seeded at a density of 105 cells/mL, and BJAB cells and LCLs were cultured at a density of 3 × 105 cells/mL. Cells were treated with 2.5 μM 5-azacytidine (Sigma-Aldrich) or solvent control (H2O:acetic acid, 1:1) for 5 days. Cultured supernatants were collected, and IL-13 expression was detected by ELISA.

IL-13 neutralizing assay

EBV infected B cells or LCLs were cultured at a density at 106 or 3 × 105 cells/mL and then treated with various doses of IL-13 neutralizing antibodies (BioVision) or rabbit control IgG (DAKO). After 24- or 48-hour incubation, 1 μCi [3H]-thymidine (Moravek Biochemicals) was added to each well and then incubated for 18 or 24 hours. Cells were harvested and measured the amounts of incorporated [3H]-thymidine by β-counter (LS 6000 IC; Beckman, BD).

Results

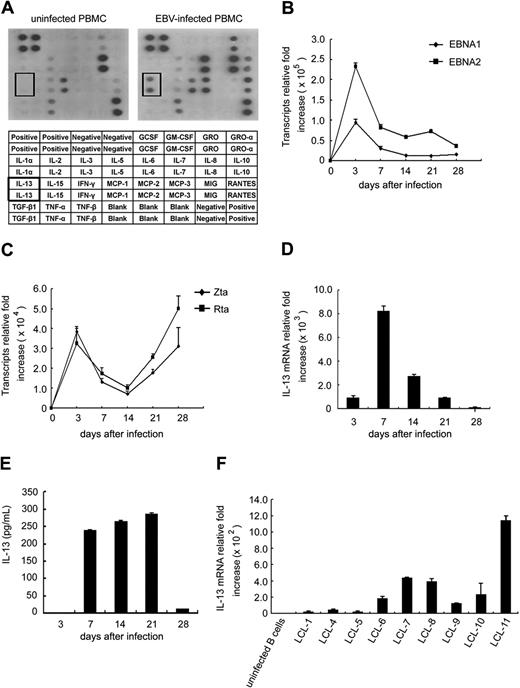

IL-13 was induced in EBV-infected B cells

We compared the cytokine expression profiles in EBV-infected and uninfected PBMCs using cytokine antibody arrays. As shown in Figure 1A, well documented cytokines, including IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, Rantes, and tumor necrosis factor-β (TNF-β) were found by the cytokine antibody arrays to be increased following infection with EBV.1,26,27 Interestingly, IL-13, chemokine growth-regulated oncogene (GRO), and monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP-2) were induced markedly in EBV-infected PBMCs. EBV can infect lymphocytes, including T cells, NK cells, and B cells, but its major targets are B cells. CD21 is expressed on the B-cell surface and serves as a receptor for EBV, which enters through interaction with the viral gp350 protein.1 To clarify whether IL-13, GRO, and MCP-2 expression were induced in EBV-infected B cells, their expression was detected by cytokine antibody arrays and RT-Q-PCR on day 7 after infection with EBV. Indeed, only IL-13 was induced in EBV-infected B cells, and GRO and MCP-2 were not (data not shown). Furthermore, the kinetics of expression of transcripts encoding latent (EBNA1 and EBNA2) and lytic (Zta and Rta) viral proteins were analyzed in EBV-infected B cells by RT-Q-PCR. The expression of EBNA1 and EBNA2 reached a peak on day 3 in the early phase of infection, then declined and was maintained at a stable level until the end of the time course (Figure 1B). Furthermore, expression of Zta and Rta increased at day 3, then decreased, and later became elevated (Figure 1C). These results indicate that EBV can infect primary B cells successfully. In addition, IL-13 transcripts were up-regulated on day 3, peaked on day 7, and then lower expression levels were maintained until the end of time course (Figure 1D). Furthermore, IL-13 protein could be detected, and stable expression was maintained from day 7 to day 21 after infection (Figure 1E). However, production of IL-13 was lower on day 28 after infection (Figure 1D). Next, we investigated IL-13 mRNA expression in 9 EBV-immortalized LCLs, because the variation among individual LCLs potentially was of interest. Compared with primary B cells, 50- to 1200-fold higher levels of IL-13 transcript expression were observed in the various LCLs tested (Figure 1F), suggesting that EBV-immortalized LCLs express IL-13 constitutively. Notably, each LCL line, established from an individual donor, exhibited a characteristic level of EBV-mediated IL-13 expression. Thus, IL-13 expression was induced during EBV immortalization of primary B cells and maintained constitutively in LCLs, implying that EBV-induced IL-13 expression might be controlled by EBV products.

IL-13 production is induced after EBV infection. (A) PBMCs were infected with EBV or not infected, and supernatants were collected on day 7 after infection. Expression of cytokines in supernatants was measured using the human cytokine antibody array III. Each spot on the blot represents 1 cytokine, and each cytokine was duplicated. The cytokines tested are listed in the table under the blot. (B-F) CD19-positive B cells were infected with EBV, and RNA was extracted at the times indicated. The relative fold increase of transcript expression was normalized by the amount of RNA from uninfected B cells. RNA and supernatants were pooled from 6 individual donors for 1 experiment. A representative of 2 independent experiments is shown. (B) Expression of viral latent EBNA1 and EBNA2 genes was detected by RT-Q-PCR. (C) Expression of viral lytic genes (Zta and Rta) was detected by RT-Q-PCR. (D) Expression of IL-13 transcripts was measured by RT-Q-PCR. (E) IL-13 protein secreted in cultured medium was quantified by ELISA. (F) RNA was extracted from 9 LCL cells, and the IL-13 transcripts were examined by RT-Q-PCR. The relative fold of transcript expression was normalized by the amount of RNA from primary uninfected B cells.

IL-13 production is induced after EBV infection. (A) PBMCs were infected with EBV or not infected, and supernatants were collected on day 7 after infection. Expression of cytokines in supernatants was measured using the human cytokine antibody array III. Each spot on the blot represents 1 cytokine, and each cytokine was duplicated. The cytokines tested are listed in the table under the blot. (B-F) CD19-positive B cells were infected with EBV, and RNA was extracted at the times indicated. The relative fold increase of transcript expression was normalized by the amount of RNA from uninfected B cells. RNA and supernatants were pooled from 6 individual donors for 1 experiment. A representative of 2 independent experiments is shown. (B) Expression of viral latent EBNA1 and EBNA2 genes was detected by RT-Q-PCR. (C) Expression of viral lytic genes (Zta and Rta) was detected by RT-Q-PCR. (D) Expression of IL-13 transcripts was measured by RT-Q-PCR. (E) IL-13 protein secreted in cultured medium was quantified by ELISA. (F) RNA was extracted from 9 LCL cells, and the IL-13 transcripts were examined by RT-Q-PCR. The relative fold of transcript expression was normalized by the amount of RNA from primary uninfected B cells.

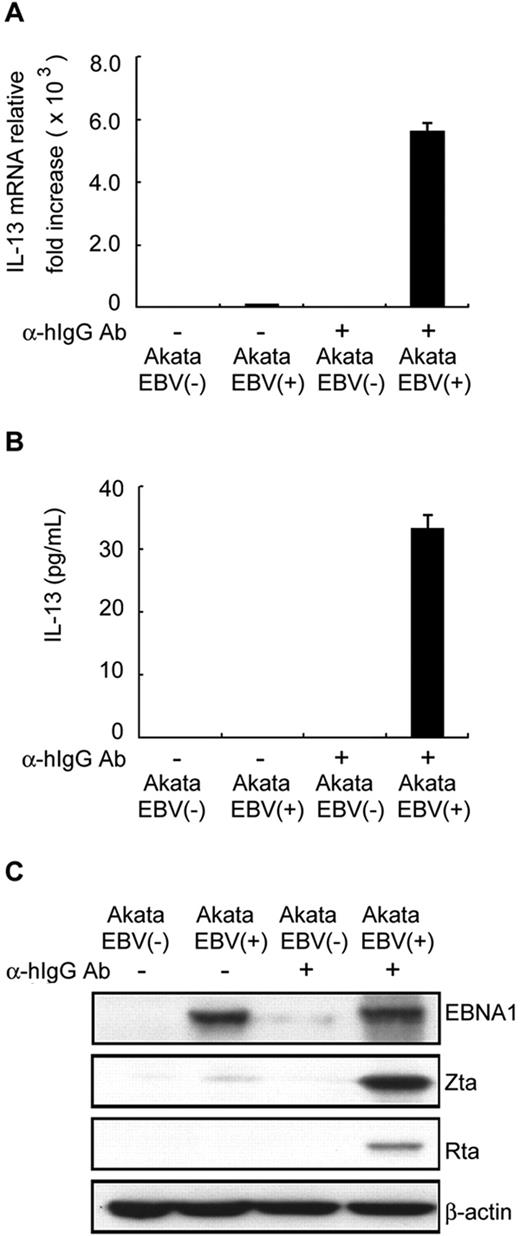

EBV lytic cycle progression induced IL-13 expression

Cytokine expression in EBV-infected cells, including IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, TNF-α, TNF-β, Rantes, macrophage inflammatory protein-1α/β (MIP-1α/β), and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), has been reported to be mediated by EBV latent or lytic products.1,26,27 To determine which EBV product is responsible for IL-13 induction, EBV-positive, and EBV-negative Akata B-cell lines were used in the following study. As shown in Figure 2A and B, IL-13 transcripts and proteins were expressed at only very low or undetectable levels in the latent state of EBV-positive Akata cells, compared with EBV-negative Akata cells. Notably, IL-13 transcripts and proteins were elevated significantly after lytic cycle progression induced in EBV-positive Akata cells by IgG cross-linking (Figure 2A-B). However, IL-13 expression could not be detected in EBV-negative Akata cells even when stimulated by IgG cross-linking. This result suggested that IL-13 production is induced mainly by events during EBV reactivation, rather than by those triggered by stimulation with IgG. The expression of a latent protein (ENBA1) and lytic proteins (Zta and Rta) in IgG-treated EBV-positive Akata cells is shown in Figure 2C. Our results demonstrate clearly that IgG cross-linking induced lytic cycle progression in EBV-positive Akata cells, suggesting that IL-13 production was induced principally by EBV lytic products.

EBV lytic cycle progression enhances IL-13 expression. EBV negative (−) or EBV positive (+) Akata B-cell lines were treated with or without 10 μg/mL goat anti–human IgG antibody (α-hIgG Ab). RNA, supernatants, and cell lysates were harvested after 48 hours. Expression of IL-13 transcripts and protein was measured by RT-Q-PCR (A) and ELISA (B). The relative expression levels of IL-13 transcripts were normalized by the amount of IL-13 expressed in EBV(−) Akata B cells. (C) Expression of EBV latent (EBNA1) or lytic (Zta and Rta) proteins was detected by Western blot analysis; β-actin served as the internal control.

EBV lytic cycle progression enhances IL-13 expression. EBV negative (−) or EBV positive (+) Akata B-cell lines were treated with or without 10 μg/mL goat anti–human IgG antibody (α-hIgG Ab). RNA, supernatants, and cell lysates were harvested after 48 hours. Expression of IL-13 transcripts and protein was measured by RT-Q-PCR (A) and ELISA (B). The relative expression levels of IL-13 transcripts were normalized by the amount of IL-13 expressed in EBV(−) Akata B cells. (C) Expression of EBV latent (EBNA1) or lytic (Zta and Rta) proteins was detected by Western blot analysis; β-actin served as the internal control.

The EBV lytic protein, Zta, plays a key role in IL-13 expression

It is well known that EBV encodes several proteins that act as transcriptional transactivators and affect critically cellular and viral gene expression.4 The latent proteins EBNA1, EBNA2, and LMP1 have been reported to play an essential role in the immortalization of EBV-infected B cells.4 LMP2A is a key regulator of B-cell survival.2,4 The lytic proteins Zta and Rta are transcriptional activators that regulate expression of several viral and cellular genes that are required for lytic cycle progression.4 To determine which EBV products contribute directly to the expression of IL-13, the expression of individual viral products (EBNA1, EBNA2, LMP1, LMP2A, Zta, or Rta) was examined in EBV-negative BJAB cells. Approximately 17-fold induction of IL-13 transcripts was observed in cells expressing Zta, compared with cells expressing other viral products (Figure 3A). Furthermore, IL-13 expression increased in a dose-dependent manner following Zta expression in lentivirus-infected BJAB cells (Figure 3B). Thus, these results support further a role for the EBV lytic transactivator, Zta, in IL-13 induction during EBV infection. To confirm the expression of IL-13 mRNA and protein following Zta expression, EBV-negative and IL-13-producing L428 cells were used as targets for the Zta-expressing lentivirus. As shown in Figure 3C and D, approximately 20- to 30-fold induction of IL-13 transcripts and proteins were observed 4 to 6 days after expression of Zta protein in lentivirus-infected L428 cells. Expression of IL-13 protein was increased from an average of 30 pg/mL in the pSIN control supernatant to approximately 1000 pg/mL in the Zta-expressing cell supernatant (Figure 3D). Because only a small proportion of LCLs underwent spontaneous lytic cycle progression,4 we asked whether the expression of IL-13 transcripts were enhanced in LCLs overexpressing Zta. As shown in Figure 3E, 2- to 12-fold enhancement of IL-13 transcript expression was detected in all Zta-expressing LCLs (pSIN-vector versus pSIN-Zta). To demonstrate further that IL-13 production is mediated by Zta expression, knockdown of Zta was carried out in Zta expressing LCLs. In Figure 3F, 30% to 60% suppression of IL-13 mRNA expression was seen when Zta expression was decreased using an siZta approach, suggesting that EBV-encoded Zta proteins are responsible for IL-13 gene expression. Taken together, Zta expression alone could induce IL-13 expression, not only in EBV-negative BJAB and L428 cells, but also in EBV-immortalized LCLs.

Expression of the EBV lytic protein, Zta, contributed to induction of IL-13. (A) BJAB cells were transfected with plasmids expressing EBNA1, EBNA2, LMP1, LMP2A, Zta, or Rta. RNA was extracted from each transfectant at 48 hours after transfection, and IL-13 transcripts were measured by RT-Q-PCR. (B) BJAB cells were infected with pSIN-vector or pSIN-Zta at the MOI indicated. RNA and cell lysates were harvested from each transfectant at 5 days after infection. IL-13 transcripts were measured by RT-Q-PCR (top panel), and Zta expression was detected by Western blot analysis (bottom panel; vertical lines have been inserted to indicate a repositioned gel lane). (C,D) L428 cells were infected with pSIN-Zta or pSIN-vector at an MOI of 4. Cell lysates, RNA, and supernatants were collected on days 4, 5, and 6 after infection. IL-13 transcripts were measured by RT-Q-PCR, and then relative expression of IL-13 transcripts was normalized to the amounts of IL-13 expressed in pSIN-vector transfected cells (panel C top). Zta expression was detected by Western blot analysis, and β-actin was used as an internal control (panel C bottom). Meanwhile, IL-13 protein in supernatants was quantified by ELISA (D). (E) In total, 6 LCLs cells were infected with pSIN-Zta or pSIN-vector lentivirus at an MOI of 4, and RNA and cell lysates were harvested after 7 days. Expression of IL-13 transcripts was detected by RT-Q-PCR, and the relative fold was normalized with the amounts of IL-13 mRNA in pSIN-vector lentivirus control cells (top panel). EBNA2 and Zta expression were measured by Western blot analyses, and β-actin was used as an internal control (bottom panel; vertical lines have been inserted to indicate a repositioned gel lane). (F) LCLs were infected with pLKO-siZta or pLKO-siLuciferase lentivirus, and then RNA and cell lysates were harvested on day 14 after infection. Expression of IL-13 transcripts was detected by RT-Q-PCR, and the relative fold was normalized with the amounts of IL-13 mRNA in pLKO-siLuciferase lentivirus infected cells (top panel). Zta expression was measured by Western blot analysis, and α-tubulin was used as an internal control (bottom panel).

Expression of the EBV lytic protein, Zta, contributed to induction of IL-13. (A) BJAB cells were transfected with plasmids expressing EBNA1, EBNA2, LMP1, LMP2A, Zta, or Rta. RNA was extracted from each transfectant at 48 hours after transfection, and IL-13 transcripts were measured by RT-Q-PCR. (B) BJAB cells were infected with pSIN-vector or pSIN-Zta at the MOI indicated. RNA and cell lysates were harvested from each transfectant at 5 days after infection. IL-13 transcripts were measured by RT-Q-PCR (top panel), and Zta expression was detected by Western blot analysis (bottom panel; vertical lines have been inserted to indicate a repositioned gel lane). (C,D) L428 cells were infected with pSIN-Zta or pSIN-vector at an MOI of 4. Cell lysates, RNA, and supernatants were collected on days 4, 5, and 6 after infection. IL-13 transcripts were measured by RT-Q-PCR, and then relative expression of IL-13 transcripts was normalized to the amounts of IL-13 expressed in pSIN-vector transfected cells (panel C top). Zta expression was detected by Western blot analysis, and β-actin was used as an internal control (panel C bottom). Meanwhile, IL-13 protein in supernatants was quantified by ELISA (D). (E) In total, 6 LCLs cells were infected with pSIN-Zta or pSIN-vector lentivirus at an MOI of 4, and RNA and cell lysates were harvested after 7 days. Expression of IL-13 transcripts was detected by RT-Q-PCR, and the relative fold was normalized with the amounts of IL-13 mRNA in pSIN-vector lentivirus control cells (top panel). EBNA2 and Zta expression were measured by Western blot analyses, and β-actin was used as an internal control (bottom panel; vertical lines have been inserted to indicate a repositioned gel lane). (F) LCLs were infected with pLKO-siZta or pLKO-siLuciferase lentivirus, and then RNA and cell lysates were harvested on day 14 after infection. Expression of IL-13 transcripts was detected by RT-Q-PCR, and the relative fold was normalized with the amounts of IL-13 mRNA in pLKO-siLuciferase lentivirus infected cells (top panel). Zta expression was measured by Western blot analysis, and α-tubulin was used as an internal control (bottom panel).

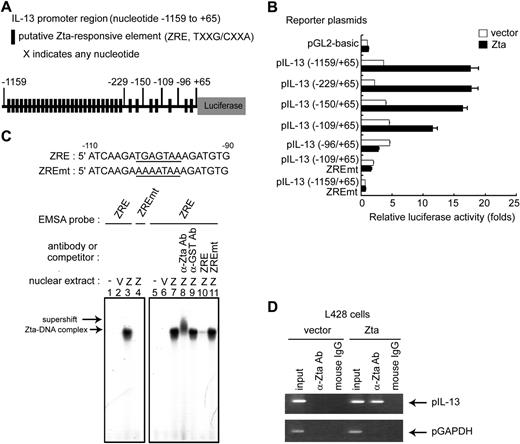

IL-13 gene expression is mediated by Zta transactivation activity

Zta protein is not only an initiator of the EBV lytic cycle cascade, but also a transcriptional factor that regulates directly the expression of a set of cellular genes.4 To determine whether Zta binds directly to the IL-13 promoter and so transactivates IL-13 gene expression, an IL-13 promoter fragment spanning position −1159 to +65 was constructed. Based on sequence analysis, 34 potential Zta responsive elements (ZRE: TXXG/CXXA, X indicates any nucleotide) were identified in this region of the IL-13 promoter (Figure 4A). A series of promoter mutant constructs were generated with 5′ deletions to investigate the Zta responsive elements. As shown in Figure 4B, approximately 18-fold induction of the IL-13 promoter, spanning position −1159 to +65, was observed when Zta was expressed. Based on serial 5′ deletions of the IL-13 promoter, Zta-induction was shown to be targeted through the sequences from −109 to +65. In particular, deletion of the region −109 to −96 almost completely abolished luciferase reporter activity. Indeed, mutation of the ZRE within the regions −1159 to +65 and −109 to +65 suppressed the induction of IL-13 promoter activity by Zta (Figure 4B). Experiments with various deletion and other mutations of the IL-13 promoter indicated a single and crucial Zta binding site located between nucleotide positions −109 and −96. To determine whether Zta can bind directly to the IL-13 promoter, EMSAs were performed in HEK293T cells transiently expressing Zta. As shown in Figure 4C, a complex of wild-type ZRE probe and Zta protein was found in extracts of Zta-expressing cells (Figure 4C lanes 3 and 7) but no complex was detected in extracts of Zta-expressing cells when the mutant ZRE probe was coincubated (Figure 4C lane 4). The complex of wild-type ZRE and Zta was recognized specifically by anti-Zta antibody (supershift band; Figure 4C lane 8) but not by a control, anti-GST antibody (Figure 4C lane 9). Furthermore, a 30-fold excess of nonlabeled wild-type oligonucleotides completely abolished the binding between Zta and the radiolabeled wild-type probe (Figure 4C lane 10), but an excess of nonlabeled mutant oligonucleotides had no such effect (Figure 4C lane 11). These results confirmed that Zta bound specifically to the IL-13 promoter in the region from −103 to −97. To confirm that Zta binds to the endogenous IL-13 promoter under physiologic conditions, L428 cells were infected with a lentivirus carrying a Zta-expression cassette, and a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed. As shown in Figure 4D, data from the ChIP assay indicated that Zta protein could bind to the IL-13 promoter sequence. In combination, these data confirm that Zta-induction of IL-13 expression is through direct interaction with a specific binding site in the IL-13 promoter.

Mechanism involved in Zta-mediated IL-13 gene expression. (A) Schematic illustration of the IL-13 promoter that drives the luciferase gene in the reporter plasmid; putative ZRE sequences are indicated. The IL-13 promoter contains 34 putative ZRE regions in the sequence from −1159 to +65. (B) HEK293T cells were transfected with Zta-expressing plasmid or vector in combination with serial 5′-deleted pIL-13 reporter plasmids and pEGFP-C1 reporter control. After 72 hours, luciferase activities from each transfectant were normalized with the GFP intensities. Zta-driven fold activation for each reporter was calculated by normalizing luciferase activities for the Zta transfectant versus that for the pGL2-basic vector control. (C) DNA sequences of the probes used in EMSA experiments. Bold lines indicate ZRE or ZREmt within the IL-13 promoter sequences from −90 to −110. Nuclear extracts were harvested at 72 hours after transfection of pRC vector or pRC-Zta in HEK293T cells. The binding of Zta with 32P-labeled ZRE (lanes 3 and 7) or ZREmt (lane 4) probes was examined by EMSA. The supershift signal represents the complex of Zta and IL-13 promoter DNA and was detected by the addition of specific anti-Zta (lane 8) or anti-GST control (lane 9) antibodies. For the competition EMSA, a 30-fold excess of wild-type ZRE (lane 10) or ZREmt (lane 11) oligonucleotides was added to the reaction mixture. (D) A ChIP experiment was carried out as described previously. L428 cells were infected with pSIN-Zta or pSIN-vector lentivirus for 5 days. DNA-protein complexes were immunoprecipitated with anti-Zta antibody or mouse IgG (negative control). IL-13 promoter DNA (pIL-13, from nt −232 to +66) and control GAPDH promoter DNA (pGAPDH, from nt −93 to +64) were detected in the immunoprecipitates by PCR. Total DNA was harvested from L428 cells and used as the input control.

Mechanism involved in Zta-mediated IL-13 gene expression. (A) Schematic illustration of the IL-13 promoter that drives the luciferase gene in the reporter plasmid; putative ZRE sequences are indicated. The IL-13 promoter contains 34 putative ZRE regions in the sequence from −1159 to +65. (B) HEK293T cells were transfected with Zta-expressing plasmid or vector in combination with serial 5′-deleted pIL-13 reporter plasmids and pEGFP-C1 reporter control. After 72 hours, luciferase activities from each transfectant were normalized with the GFP intensities. Zta-driven fold activation for each reporter was calculated by normalizing luciferase activities for the Zta transfectant versus that for the pGL2-basic vector control. (C) DNA sequences of the probes used in EMSA experiments. Bold lines indicate ZRE or ZREmt within the IL-13 promoter sequences from −90 to −110. Nuclear extracts were harvested at 72 hours after transfection of pRC vector or pRC-Zta in HEK293T cells. The binding of Zta with 32P-labeled ZRE (lanes 3 and 7) or ZREmt (lane 4) probes was examined by EMSA. The supershift signal represents the complex of Zta and IL-13 promoter DNA and was detected by the addition of specific anti-Zta (lane 8) or anti-GST control (lane 9) antibodies. For the competition EMSA, a 30-fold excess of wild-type ZRE (lane 10) or ZREmt (lane 11) oligonucleotides was added to the reaction mixture. (D) A ChIP experiment was carried out as described previously. L428 cells were infected with pSIN-Zta or pSIN-vector lentivirus for 5 days. DNA-protein complexes were immunoprecipitated with anti-Zta antibody or mouse IgG (negative control). IL-13 promoter DNA (pIL-13, from nt −232 to +66) and control GAPDH promoter DNA (pGAPDH, from nt −93 to +64) were detected in the immunoprecipitates by PCR. Total DNA was harvested from L428 cells and used as the input control.

Zta overexpression does not affect methylation of the IL-13 promoter

At present, restriction of promoter methylation is a recognized mechanism of regulation of IL-13 expression. Hypermethylation of the IL-13 proximal promoter plays an important role in silencing IL-13 expression in Th1 cells.28 Therefore, we sought to determine whether methylation of the IL-13 promoter was altered in EBV-immortalized LCLs. As shown in Figure 5A, all 7 CpG sites in the IL-13 promoter between −280 and +58 were methylated in primary uninfected B cells and LCLs, suggesting that the methylation profile in the IL-13 promoter sequence between −280 and +58 was not altered during EBV infection. In addition, no CpG sites are methylated in IL-13-producing L428 cells, and all sites are methylated in IL-13-nonproducing BJAB cells (Figure 5A). Furthermore, the methylation patterns of the IL-13 promoter were examined in LCLs overexpressing Zta, in which IL-13 expression was increased, as shown in Figure 3E. Data from bisulfite sequencing indicated that all 7 CpG sites in the IL-13 promoter of all LCLs tested remain methylated, whether or not Zta was expressed (Figure 5B). The nonmethylated pattern of the IL-13 promoter in L428 cells also was maintained (Figure 5B). In addition, to determine whether IL-13 expression could be enhanced by demethylation, cells were treated with the demethylating drug, 5-azacytidine. IL-13 protein in the supernatant was elevated after 5-azacytidine treatment of all LCLs tested, but not in the supernatants of EBV-negative BJAB cells or L428 cells (Figure 5C). These results indicate that Zta-induced expression of IL-13 does not involve in modification of the methylation pattern of the IL-13 promoter. Thus, Zta-mediated induction of IL-13 is independent of regulation of methylation of the IL-13 promoter.

Methylation patterns were examined in IL-13 promoter sequences from −280 to +58. (A) The IL-13 promoter contains 7 CpG sites at the positions indicated, between −280 and +58 relative to the transcription start site. Genomic DNA was harvested from L428 cells, BJAB cells, primary uninfected B cells, and 11 LCLs, and CpG methylation was analyzed by bisulfite sequencing. Numbers (1-7) under the sequence represents the CpG position; [□], nonmethylated CpG; [■], methylated CpG. (B) In total, 6 LCLs cells were infected with pSIN-Zta or pSIN-vector lentivirus at an MOI of 4. Genomic DNA was extracted, and CpG methylation was analyzed by bisulfite sequencing after 7 days. (C) L428 cells, BJAB cells, and a total of 10 LCLs were treated with or without 2.5 μM 5-azacytidine for 5 days. Cultured supernatants were harvested, and IL-13 expression was measured by ELISA.

Methylation patterns were examined in IL-13 promoter sequences from −280 to +58. (A) The IL-13 promoter contains 7 CpG sites at the positions indicated, between −280 and +58 relative to the transcription start site. Genomic DNA was harvested from L428 cells, BJAB cells, primary uninfected B cells, and 11 LCLs, and CpG methylation was analyzed by bisulfite sequencing. Numbers (1-7) under the sequence represents the CpG position; [□], nonmethylated CpG; [■], methylated CpG. (B) In total, 6 LCLs cells were infected with pSIN-Zta or pSIN-vector lentivirus at an MOI of 4. Genomic DNA was extracted, and CpG methylation was analyzed by bisulfite sequencing after 7 days. (C) L428 cells, BJAB cells, and a total of 10 LCLs were treated with or without 2.5 μM 5-azacytidine for 5 days. Cultured supernatants were harvested, and IL-13 expression was measured by ELISA.

IL-13 is required for the growth of EBV-infected B cells and LCLs

To investigate the involvement of IL-13 in the early stage of EBV-induced proliferation and in long-term maintenance of growth of EBV-immortalized LCLs, cell proliferation was measured by [3H]-thymidine incorporation after blockade by IL-13 neutralizing antibody. In Figure 6A, data from [3H]-thymidine incorporation illustrate a dose-dependent suppression of cell proliferation in the presence of various amounts of IL-13 neutralizing antibody on day 7 after EBV infection of primary B cells, compared with the isotype control antibody-treated cells. EBV-mediated cell growth was inhibited almost completely after addition of 5 μg/mL IL-13 neutralizing antibody. This result suggested that EBV-induced production of IL-13 is required for B-cell proliferation. Because IL-13 transcripts were detected in all LCLs tested, we questioned whether IL-13 also is involved in maintenance of LCL proliferation. Compared with isotype control antibody treatment, 77% to 80% suppression of cell growth could be observed in all LCLs tested after addition of 5 μg/mL IL-13 neutralizing antibody (Figure 6B). Although a small proportion of the LCLs expressed Zta protein, our results indicate that autocrine and paracrine IL-13 production contributed to the maintenance of LCL growth. Thus, our data suggest that EBV-induced IL-13 expression is involved in EBV-mediated B-cell proliferation and might be involved in the pathology of EBV-driven lymphoproliferative diseases.

IL-13 is crucial for triggering the cell growth of EBV-infected primary B cells and for maintaining the proliferation of LCLs. (A) B cells purified from 2 healthy donors were infected with EBV. Five days after infection, various doses of anti–IL-13 neutralizing antibodies (α-IL-13 Ab) or rabbit IgG were added. After 24 hours incubation, [3H]-thymidine was added, incubation was continued for a further 24 hours, and the amount of [3H]-thymidine incorporation was measured. (B) LCLs were cultured for 24 hours, and various doses of anti–IL-13 neutralizing antibodies or rabbit IgG were added. After 48 hours incubation, [3H]-thymidine was added, incubation continued for 18 hours, and the amount of [3H]-thymidine incorporation was measured.

IL-13 is crucial for triggering the cell growth of EBV-infected primary B cells and for maintaining the proliferation of LCLs. (A) B cells purified from 2 healthy donors were infected with EBV. Five days after infection, various doses of anti–IL-13 neutralizing antibodies (α-IL-13 Ab) or rabbit IgG were added. After 24 hours incubation, [3H]-thymidine was added, incubation was continued for a further 24 hours, and the amount of [3H]-thymidine incorporation was measured. (B) LCLs were cultured for 24 hours, and various doses of anti–IL-13 neutralizing antibodies or rabbit IgG were added. After 48 hours incubation, [3H]-thymidine was added, incubation continued for 18 hours, and the amount of [3H]-thymidine incorporation was measured.

Discussion

EBV lytic replication has been demonstrated by elevated antibodies to EBV lytic antigens and by increasing viral titer in posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD), Hodgkin lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, and NPC patients.29-31 Furthermore, previous clinical observations have led to the hypothesis that EBV-related lymphoproliferative disorders should be more common in immunosuppressed individuals. This might be attributable to decreased EBV-specific cytotoxic CD8 T-cell responses and activation of the lytic cycle in EBV-harboring B cells, resulting in rapid proliferation of lymphocytes assisted by EBV-encoded oncoproteins, EBV-induced growth factors, survival factors, and cell cycle progressing molecules.3,4 Thus, EBV reactivation is not only a risk factor for lymphoproliferative disorders and cancer development, but also correlates with advanced stage of cancer, poor prognosis, poor therapeutic responses, and tumor recurrence after chemotherapy.31

Among the viral lytic products, EBV Zta protein is the crucial transactivator of the EBV lytic cascade and also can manipulate host gene expression.4 Indeed, Zta-knockout EBV cannot enter a complete lytic cycle, and LCLs established by Zta-knockout EBV have impaired cytokine production and the ability to produce lymphoproliferative disorders in severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice.32 In vitro, the immediate-early expression of Zta is detected in EBV-harboring cells treated with chemical or physiologic stimuli, such as TGF-β, TPA, rheumatoid factor, anti-IgG antibody, or histone deacetylase inhibitors.4,33 Pathologically, BZLF-1 mRNA and protein also can be detected in B cells from acute infectious mononucleosis and lymphoproliferative disorders, and in Reed-Sternberg cells from Hodgkin lymphoma, suggesting that Zta expression is a risk factor for lymphoproliferation and cell immortalization.4,32,34,35

Structurally, Zta is a functional homolog of AP-1 and belongs to the basic leucine zipper (bZIP) family.36 The Zta protein can be divided into 3 domains: an N-terminal transactivation domain, a central DNA binding domain, and a C-terminal dimerization domain, which can form homodimers or heterodimers with other bZIP members, such as CCAAT/enhancer binding protein α (C/EBPα).37 Furthermore, the transactivation activity of Zta can be regulated by phosphorylation or sumoylation at certain sites. As a transactivator, Zta mediates expression of host genes in EBV-associated NPC cells, including E2F cell cycle-related genes, p53, IL-8, tyrosine kinase TKT, matrix metalloproteinase-1, and early growth response 1 (Egr-1).14,38-41 In particular, Zta can stimulate the expression of Egr-1 by promoting Zta itself, as well as the Elk protein bound to the ZRE and serum response element (SRE) on the Egr-1 promoter.38 In this study, data from serial deletions and other mutations of the IL-13 promoter indicated that only the ZRE located from −103 to −97 plays an important role in Zta-mediated IL-13 expression (Figure 4), and this corresponds precisely to the AP-1 binding site. Mutation of this ZRE/AP-1 binding site abolished Zta-induced IL-13 promoter activity (Figure 4), suggesting that Zta binds directly to the putative AP-1 binding site within IL-13 promoter. It is well-known that AP-1 is a potent transcriptional regulator of cytokine gene expression, including IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-13.42 It seems that Zta can mimic AP-1 and regulate IL-13 gene expression in EBV-infected B cells.

In general, cytokine expression is determined predominantly at the transcriptional level via several regulatory factors, including chromatin structure, transactivators, repressors, and demethylation of certain CpG sites.43 In previous studies, the regulatory mechanisms of IL-13 induction in EBV-associated malignancies have not been clear, even though IL-13 has been demonstrated frequently in the biopsies of EBV-associated lymphomas.18 Using EBV-infected B cells as a model, we have provided evidence that an EBV-encoded AP-1 homolog, Zta protein, binds directly to the ZRE/AP-1 site in the IL-13 promoter and induces IL-13 expression. Based on a previous study, Zta prefers to bind and activate methylated EBV viral genomes.44 Our result demonstrated first that EBV infection or Zta overexpression could enhance IL-13 production, not only with a hypermethylated IL-13 promoter in primary B cells (Figures 1, 5) and LCLs (Figures 3 and 5), but also with a nonmethylated IL-13 promoter in L428 cells (Figures 3, 5). Therefore, Zta protein might overcome methylation of the IL-13 promoter and activate IL-13 gene expression. Based on this study, we assume that Zta expression and promoter demethylation are 2 independent factors that control IL-13 expression, at least in LCLs.

It is of interest that 2 human oncogenic viruses, EBV and HTLV-1, can induce IL-13 via their key transactivating proteins, Zta and tat, respectively.45,46 Our results indicate that Zta-induced IL-13 acts as a growth factor in EBV-infected B cells and LCLs (Figure 6). IL-13 has been detected frequently in Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin lymphoma and NK cells of chronic active EBV-infected patients. The titer of IgE, which correlates with IL-13 expression, was elevated in EBV-associated Hodgkin lymphoma.47 Furthermore, IL-13 downstream proteins, including CD23, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), human germinal center-associated lymphoma protein, macrophage-derived chemokine (MDC), thymus and activated related chemokine (TARC), and eotoxin are detected in Reed-Sternberg cells and patients with EBV reactivation.48-50 These IL-13 downstream proteins also were clearly detected by protein arrays in our EBV-infected primary B cells (data not shown). We speculated that this may be the reason that LCLs tend to clump together; this cell-to-cell interaction may be attributable to the expression of EBV-induced adherence molecules or chemoattractants, which may provide the signal for LCL proliferation. This in vitro phenomenon may explain the fact that IL-13–producing Reed-Sternberg cells cluster around macrophages, Th2 cells, and fibroblasts, which are attracted by MDC, TARC, and eotoxin in the Hodgkin lymphoma microenvironment.51,52 Thus, Zta-mediated production of IL-13 contributes to proliferation of EBV-infected B cells and, further, may provide a unique microenvironment for formation of lymphomas and immortalization of B cells.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Tim J. Harrison of the University College London (UCL) Medical School, London, United Kingdom, for reviewing the manuscript critically. We thank Yi-Li Liu and Chia-Shan Hsieh for DNA sequencing.

This work was supported by the National Science Council (grant nos. NSC96-B112-B-002-005 and NSC97-2320-B-002-003-MY3), the National Health Research Institute (grant nos. NHRI-EX97-9726BI and NHRI-EX98-9726BI), and the Department of Medical Research in National Taiwan University Hospital, and National Taiwan University (97HM00233).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: S.-C.T. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and cowrote the manuscript; S.-J.L. designed experiments, analyzed data, and cowrote the manuscript; P.-W.C. and W.-Y.L. performed experiments; T.-H.Y., H.-W.W., and C.-J.C.provided materials; and C.-H.T. guided experimental design and cowrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ching-Hwa Tsai, Rm 714, No. 1, 1st section, Jen-Ai Rd, Graduate Institute of Microbiology, College of Medicine, National Taiwan University, Taipei 10051, Taiwan; e-mail: chtsai@ntu.edu.tw.

![Figure 5. Methylation patterns were examined in IL-13 promoter sequences from −280 to +58. (A) The IL-13 promoter contains 7 CpG sites at the positions indicated, between −280 and +58 relative to the transcription start site. Genomic DNA was harvested from L428 cells, BJAB cells, primary uninfected B cells, and 11 LCLs, and CpG methylation was analyzed by bisulfite sequencing. Numbers (1-7) under the sequence represents the CpG position; [□], nonmethylated CpG; [■], methylated CpG. (B) In total, 6 LCLs cells were infected with pSIN-Zta or pSIN-vector lentivirus at an MOI of 4. Genomic DNA was extracted, and CpG methylation was analyzed by bisulfite sequencing after 7 days. (C) L428 cells, BJAB cells, and a total of 10 LCLs were treated with or without 2.5 μM 5-azacytidine for 5 days. Cultured supernatants were harvested, and IL-13 expression was measured by ELISA.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/114/1/10.1182_blood-2008-12-193375/4/m_zh89990938370005.jpeg?Expires=1765973498&Signature=uTlujw95OibZrVdik-wBcLsHdPJexcsLSeyWm6eq1L9lvQdK5peKMm-A6bTj6FtLO1ApiGGRqlOuaXV~QuNldGcoJ2~DPJeXwkUq7B3b~9KntgfAe5fRFkCs4h4Tjbcp~xxT5BSn4VuGtvnee2owRwzxWlXz5RRIsQoywNhE8Rh5wSnvc3ScoGW7he7O3U4lJuJxyCO4l-g15iEYNakREICxEOQfVYeKtIur0gcxyBKNjB1ZJ1R5UC6Wm8J6Ai4MXpsHqvySrTzUhSm98Ii9N5RVBlcrrlQ3CQjnnLOXQ6BNVM~KLcrPTM3rnxW368kXkwgt9pgIB8KmHf2WIdoSnA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 6. IL-13 is crucial for triggering the cell growth of EBV-infected primary B cells and for maintaining the proliferation of LCLs. (A) B cells purified from 2 healthy donors were infected with EBV. Five days after infection, various doses of anti–IL-13 neutralizing antibodies (α-IL-13 Ab) or rabbit IgG were added. After 24 hours incubation, [3H]-thymidine was added, incubation was continued for a further 24 hours, and the amount of [3H]-thymidine incorporation was measured. (B) LCLs were cultured for 24 hours, and various doses of anti–IL-13 neutralizing antibodies or rabbit IgG were added. After 48 hours incubation, [3H]-thymidine was added, incubation continued for 18 hours, and the amount of [3H]-thymidine incorporation was measured.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/114/1/10.1182_blood-2008-12-193375/4/m_zh89990938370006.jpeg?Expires=1765973498&Signature=27dxgmrtN0LaLrMpf2msyWcrV-4NJnl~i-Nq6641hFmz5403y5YtKXfhjt6wjmLSUOAKqfDBGrsWY-6lvfIAh0LZyW04P1pIhW7YWYbwnsVoHXTSso72Vs3wT~tENW9heJJPmMokFgrBxxjh92iFAXyEyhxSFCCgYqya~yXrUwddDX0ZwxijoC5T4XpsVTKDdgASa1t9Ju6O8i31x3t7Z56px5~qvOZYh~EfeCj5OB3gbA7hgy~1VROyIwWiLCZBPHxNvq4G7AoqFUHEssT4UuIM~9l-OBK8vn8evIGMk3BQvTvm7zTwW-ckL9ugUED8O9mC1fp4YBYuwY~LGhKX7A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal