Abstract

The eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF4E is elevated in 30% of malignancies including M4/M5 subtypes of acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The oncogenic potential of eIF4E arises from its ability to bind the 7-methyl guanosine (m7G) cap on mRNAs, thereby selectively enhancing eIF4E-dependent nuclear mRNA export and translation. We tested the clinical efficacy of targeting eIF4E in M4/M5 AML patients with a physical mimic of the m7G cap, ribavirin. Among 11 evaluable patients there were 1 complete remission (CR), 2 partial remissions (PRs), 2 blast responses (BRs), 4 stable diseases (SDs), and 2 progressive diseases (PDs). Ribavirin-induced relocalization of nuclear eIF4E to the cytoplasm and reduction of eIF4E levels were associated with clinical response. Lack of response or relapse coincided with continued or renewed nuclear localization of eIF4E. This first clinical study to target eIF4E in human malignancy demonstrates clinical activity and associated molecular responses in leukemic blasts. This trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00559091).

Introduction

Approximately 30% of malignancies, including M4/M5 acute myeloid leukemias (AML), are characterized by elevated eIF4E levels.1,2 In AML, eIF4E also accumulates in the nucleus.1 eIF4E overexpression is oncogenic in model systems,3 where it enhances mRNA export and the translation of a subset of transcripts coding for proteins involved in survival and proliferation.4 These activities require the binding of eIF4E to the mRNA 7-methyl guanosine (m7G) “cap” structure.4-6

Our preclinical studies indicated that ribavirin, a broad-spectrum antiviral drug, is a physical mimic of the m7G cap, and thus blocks eIF4E activity.7-9 M4/M5 AML specimens were growth inhibited by 1 μM ribavirin, whereas normal or M1/M2 AML specimens (with normal eIF4E levels) were inhibited only at much higher levels.8 Thus, eIF4E-overexpressing leukemic cells depend on eIF4E for growth and survival and thereby have an oncogene addiction to eIF4E.8 In cell culture, 1 μM ribavirin causes relocalization of nuclear eIF4E to the cytoplasm. This correlates with reduced eIF4E-dependent export of target transcripts such as NBS1 and cyclin D1, reduced levels of NBS1 and cyclin D1 proteins, and thus, down-regulation of eIF4E-mediated Akt activation (which requires NBS1).8-10 Micromolar plasma concentrations of ribavirin are achievable in humans with minimal toxicity.11 Thus, we conducted a clinical trial examining the efficacy and molecular effects of targeting eIF4E using ribavirin in patients with M4/M5 AML.

Methods

Eligible patients had M4/M5 AML, and relapsed or refractory disease, or were unable to undergo induction chemotherapy. Ribavirin was administered daily during each 28-day cycle for up to 6 cycles. The starting dose of ribavirin was 1000 mg/day by mouth with increases to 1400, 2000, and 2800 mg/day for lack of response at 14 days or at end of cycle. Written informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study received IRB (all sites) and Health Canada approval. ClinicalTrials.gov registry is NCT00559091. Clinical response was assessed using the Cheson criteria.12 See supplemental materials (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) for information regarding dose escalation, cell sorting, RNA/protein isolations/analysis, confocal microscopy to monitor eIF4E subcellular distribution, and mass spectrometry to monitor ribavirin plasma levels.1,13

Results and discussion

Clinical responses

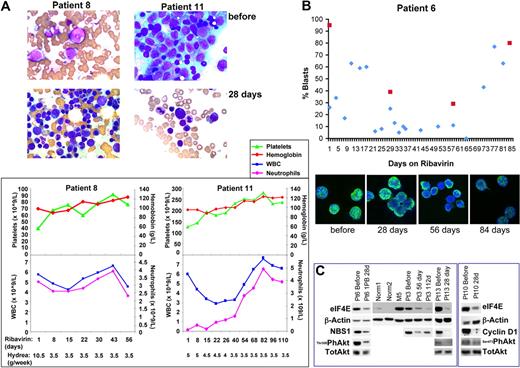

Thirteen patients were enrolled with no therapy-related toxicities observed. Two patients were not evaluable for response (< 15 days of therapy). Best responses for the 11 evaluable patients were observed by 30 days and were as follows: 1 complete remission (CR), 2 partial remissions (PRs), 2 blast responses (BRs), 4 stable diseases (SDs), and 2 progressive diseases (PDs) (Table 1). There was a marked decline in bone marrow blasts and restored normal hematopoiesis in patients 11 and 8, who had a CR and partial remission with incomplete blood count recovery (PRi), respectively (Figure 1A). Patient 6 achieved a BR with a decline from 60% to 0% in peripheral blood and 95% to 29% bone marrow blasts (Figure 1B), lasting almost 50 days. Patient 10 achieved a BR with a 66% drop in blast count lasting for 35 days, and patient 1 achieved a 48% drop in blast count with stable disease for 56 days (Table 1). Neither baseline cytogenetics, nor FLT3, nor NPM status predicted response (Table 1). Although permitted, hydrea did not affect response; for example, hydrea levels were reduced during treatment of patients 8 and 11 however they continued in PRi and CR, respectively (Figure 1). Aside from hydrea, no other cytoreductive therapies were permitted.

Summary of clinical responses observed with ribavirin treatment

| Pt no. . | Age/sex . | WHO classification . | Cytogenetics . | FLT3 mutation . | NPM1 mutation . | Prior Tx . | Disease status baseline . | Treatment duration, d . | OS, d . | Best response . | Peripheral absolute blast count, ×109/L . | Bone marrow blast (%) . | Max. dose level ribavirin, mg . | Plasma levels ribavirin at max dose, μM . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Tx . | At best response . | Before Tx . | At best response . | |||||||||||||

| 1 | 69/F | tAML | Complex* | n/a | n/a | None | Untreated | 60 | 83 | SD | 1.73 | 0.51 | 30 | 20 | 1400 | n/a |

| 3 | 46/M | NOC | Normal | ITD | N | 2× ind; 4× cons reind | Relapsed/ refractory | 137 | 137 | SD | 47.4 | 15.5 | 94 | n/a | 2800 | 5 |

| 5 | 54/M | RGA | 46, XY, t(6;11) (q27;q23) | n/a | n/a | 2× ind; 1× cons; haploT | Relapsed | 27 | 27 | PD | 0.04 | 3.6 | 90 | n/a | 1000 | n/a |

| 6 | 77/F | NOC | Normal | ITD | Y | None | Untreated | 142 | 276+ | BR | 23.3 | 0 | 95 | 29 | 2000 | 26.2 |

| 7 | 60/M | RGA | 46, XY, t(9;11) (p22;q23) | ITD | N | 1× ind; 1× cons | Relapsed | 104 | 120 | PR* | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1000 | 9.3 |

| 8 | 70/M | NOC | 45, X,−Y | ITD | Y | 1× ind;1× cons; autoPBSCT | Relapsed | 93 | 176+ | PRi | 0.06 | 0 | 65 | 10 | 2000 | 17 |

| 9 | 44/M | NOC | n/a | TKD | Y | 1× ind;4× cons;2× reind | Relapsed/ refractory | 33 | 33 | PD | 4.76 | 3.46 | n/a | n/a | 1400 | 36 |

| 10 | 56/F | NOC | Normal | ITD | N | 1× ind; 4× cons | Relapsed | 119 | 148+ | BR | 12.1 | 0.6 | 88 | 46 | 2000 | 14.8 |

| 11 | 77/M | MLD | Normal | ITD | N | None | Untreated | 111+ | 111+ | CR | 0.06 | 0 | 72 | 4 | 1000 | 14.7 |

| 12 | 79/F | RGA | 46, XX, inv(16) (p13q22) | ITD | N | None | Untreated | 19 | 104+ | SD | 0.78 | n/a | 85 | 90 | 1000 | 15.3 |

| 13 | 72/M | MLD | Normal | ITD | Y | Low Ara-C + sorafenib | Relapsed | 32 | 39 | SD | 26.1 | 32.6 | 95 | 95 | 2000 | 14.2 |

| Pt no. . | Age/sex . | WHO classification . | Cytogenetics . | FLT3 mutation . | NPM1 mutation . | Prior Tx . | Disease status baseline . | Treatment duration, d . | OS, d . | Best response . | Peripheral absolute blast count, ×109/L . | Bone marrow blast (%) . | Max. dose level ribavirin, mg . | Plasma levels ribavirin at max dose, μM . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Tx . | At best response . | Before Tx . | At best response . | |||||||||||||

| 1 | 69/F | tAML | Complex* | n/a | n/a | None | Untreated | 60 | 83 | SD | 1.73 | 0.51 | 30 | 20 | 1400 | n/a |

| 3 | 46/M | NOC | Normal | ITD | N | 2× ind; 4× cons reind | Relapsed/ refractory | 137 | 137 | SD | 47.4 | 15.5 | 94 | n/a | 2800 | 5 |

| 5 | 54/M | RGA | 46, XY, t(6;11) (q27;q23) | n/a | n/a | 2× ind; 1× cons; haploT | Relapsed | 27 | 27 | PD | 0.04 | 3.6 | 90 | n/a | 1000 | n/a |

| 6 | 77/F | NOC | Normal | ITD | Y | None | Untreated | 142 | 276+ | BR | 23.3 | 0 | 95 | 29 | 2000 | 26.2 |

| 7 | 60/M | RGA | 46, XY, t(9;11) (p22;q23) | ITD | N | 1× ind; 1× cons | Relapsed | 104 | 120 | PR* | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1000 | 9.3 |

| 8 | 70/M | NOC | 45, X,−Y | ITD | Y | 1× ind;1× cons; autoPBSCT | Relapsed | 93 | 176+ | PRi | 0.06 | 0 | 65 | 10 | 2000 | 17 |

| 9 | 44/M | NOC | n/a | TKD | Y | 1× ind;4× cons;2× reind | Relapsed/ refractory | 33 | 33 | PD | 4.76 | 3.46 | n/a | n/a | 1400 | 36 |

| 10 | 56/F | NOC | Normal | ITD | N | 1× ind; 4× cons | Relapsed | 119 | 148+ | BR | 12.1 | 0.6 | 88 | 46 | 2000 | 14.8 |

| 11 | 77/M | MLD | Normal | ITD | N | None | Untreated | 111+ | 111+ | CR | 0.06 | 0 | 72 | 4 | 1000 | 14.7 |

| 12 | 79/F | RGA | 46, XX, inv(16) (p13q22) | ITD | N | None | Untreated | 19 | 104+ | SD | 0.78 | n/a | 85 | 90 | 1000 | 15.3 |

| 13 | 72/M | MLD | Normal | ITD | Y | Low Ara-C + sorafenib | Relapsed | 32 | 39 | SD | 26.1 | 32.6 | 95 | 95 | 2000 | 14.2 |

Tx indicates transplantation; M, male; F, female; d, days; complex*, 46, XX, del(5)(q13q35)/45, XX,+1, dic(1;11)(p11;q13), t(1;3)(p13;q26), −4, der(5)t(5;11)(q31;q13), der(?16)t(4;?16)(q12;?q10), der(19)t(19;?)(q13.4;?); tAML, therapy-related AML; RGA, AML with recurrent genetic abnormality; NOC, AML not otherwise categorized; MLD, AML with multilineage dysplagia; ITD, internal tandem duplication; TKD, tyrosine kinase domain point mutation; ind, induction; cons, consolidation; haploT, haploidentical allotransplantation; autoPBSCT, autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation; OS, overall survival; CR, complete remission; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; BR, blast response; PRi, partial remission with incomplete blood count recovery; PR*, disappearance/regression of skin lesions; n/a, not available; +, continuing; Y, yes; N, no.

It is noteworthy that patient 3 entered the trial with a diagnosis of M4 AML, but this was later modified to M1. Patient 3 continued treatment because he had elevated eIF4E levels (Figure 1C), which is unusual for M1 AML.14 Patient 3 weighed 160 kg, and thus even at 2800 mg/day ribavirin, achieved plasma concentrations of only 5 μM. In contrast, other patients achieved higher concentrations of ribavirin at lower doses.

Ribavirin treatment targets eIF4E activity and localization in patients. (A) Top panels show bone marrow specimens for patients 8 (touch print, due to dry aspirate) and 11 (squash preparation) prior to therapy. Note the abundance of blasts. Immediately below, panels show response after 28 days of therapy. Patient 8 achieved PRi and patient 11, a CR. Both exhibit a restoration of hematopoiesis. This is reflected in the improvement in peripheral blood counts, particularly platelets and neutrophils, as shown in the graphs in the bottom panels. Hydrea levels are shown below the graphs indicating that response did not depend on hydrea. As well, white blood cell (WBC) counts remained normal despite decreasing hydrea doses. Squash preparations of bone marrow aspirates and touch prints of bone marrow biopsies were air-dried and stained with Wright-Giemsa. The Leica DM2 LB2 microscope with the Leica H3X PL Fluotar 100× objective lens 1.3 numeric aperture (Leica) and oil immersion were used to examine the specimens. The Infinity 1-3C (color) camera was used to capture images on the Infinity Analyze image acquisition software (Lumenera Corporation). (B, top panel) Ribavirin treatment lowered blast counts. Plot of percentage of peripheral (blue) or bone marrow (red) blasts versus treatment day for patient 6. (Bottom panel) Ribavirin treatment led to relocalization of eIF4E. Immunohistochemistry was carried out as described where cells were stained for eIF4E and DAPI.1,13 Cells were immunostained with an eIF4E mAb directly conjugated to FITC (BD Bioscience). Specimens were mounted in Vectashield with DAPI (Vector Laboratories). Channels were recorded separately with no cross talk observed between channels. Micrographs were collected on a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSM510; Carl Zeiss) using a 100× objective with a numeric aperture of 1.4, with 2× digital zoom at room temperature. Images were displayed using Photoshop CS2 (Adobe). Micrographs represent single optical sections through the plane of the cell. (C) eIF4E activity and levels were reduced by ribavirin treatment in patients. Western blot analysis was carried out using the antibodies indicated. Antibodies for immunoblotting were obtained from Cell Signaling unless otherwise mentioned: mAb anti-eIF4E (BD Bioscience); pAb anti-NBS; pAb anti–cyclin D1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); pAb anti-Akt; anti–phospho Thr308 or Ser473 Akt; and mAb anti-β-actin (AC-15; Sigma -Aldrich). As expected, similar reductions were seen for either Thr308 or Ser473 phosphorylation of Akt as seen in cell culture.11

Ribavirin treatment targets eIF4E activity and localization in patients. (A) Top panels show bone marrow specimens for patients 8 (touch print, due to dry aspirate) and 11 (squash preparation) prior to therapy. Note the abundance of blasts. Immediately below, panels show response after 28 days of therapy. Patient 8 achieved PRi and patient 11, a CR. Both exhibit a restoration of hematopoiesis. This is reflected in the improvement in peripheral blood counts, particularly platelets and neutrophils, as shown in the graphs in the bottom panels. Hydrea levels are shown below the graphs indicating that response did not depend on hydrea. As well, white blood cell (WBC) counts remained normal despite decreasing hydrea doses. Squash preparations of bone marrow aspirates and touch prints of bone marrow biopsies were air-dried and stained with Wright-Giemsa. The Leica DM2 LB2 microscope with the Leica H3X PL Fluotar 100× objective lens 1.3 numeric aperture (Leica) and oil immersion were used to examine the specimens. The Infinity 1-3C (color) camera was used to capture images on the Infinity Analyze image acquisition software (Lumenera Corporation). (B, top panel) Ribavirin treatment lowered blast counts. Plot of percentage of peripheral (blue) or bone marrow (red) blasts versus treatment day for patient 6. (Bottom panel) Ribavirin treatment led to relocalization of eIF4E. Immunohistochemistry was carried out as described where cells were stained for eIF4E and DAPI.1,13 Cells were immunostained with an eIF4E mAb directly conjugated to FITC (BD Bioscience). Specimens were mounted in Vectashield with DAPI (Vector Laboratories). Channels were recorded separately with no cross talk observed between channels. Micrographs were collected on a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSM510; Carl Zeiss) using a 100× objective with a numeric aperture of 1.4, with 2× digital zoom at room temperature. Images were displayed using Photoshop CS2 (Adobe). Micrographs represent single optical sections through the plane of the cell. (C) eIF4E activity and levels were reduced by ribavirin treatment in patients. Western blot analysis was carried out using the antibodies indicated. Antibodies for immunoblotting were obtained from Cell Signaling unless otherwise mentioned: mAb anti-eIF4E (BD Bioscience); pAb anti-NBS; pAb anti–cyclin D1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); pAb anti-Akt; anti–phospho Thr308 or Ser473 Akt; and mAb anti-β-actin (AC-15; Sigma -Aldrich). As expected, similar reductions were seen for either Thr308 or Ser473 phosphorylation of Akt as seen in cell culture.11

Patient 7 had aleukemic leukemia cutis at enrollment. We observed disappearance of some skin lesions by day 28. Pretreatment skin lesion biopsies had elevated eIF4E levels. By day 100, eIF4E levels and lesion depth were reduced (supplemental Figure 1). There was rapid progression thereafter. Thus, ribavirin may also target extramedullary disease.

Molecular responses

Molecular response was assessed in patients with sufficient material for analysis. Prior to therapy, all patients examined had elevated eIF4E levels versus healthy controls (supplemental Table 1). Typically, levels were elevated 3- to 8-fold. With a single exception, patients receiving 28+ days of therapy had a 2- to 10-fold drop in eIF4E RNA levels by day 28, with these levels remaining reduced for the duration of treatment, in some cases 112+ days (supplemental Table 1). In addition, relocalization of eIF4E from the nucleus to the cytoplasm was observed by 28 to 56 days for all patients except patient 9 (supplemental Figures 2-3). These observations coincided with a reduction of NBS1 and cyclin D1 protein levels by day 28, and a reduction in Akt phosphorylation for all patients studied (Figure 1C). Sufficient material was obtained to directly monitor mRNA export for patient 10. As expected, we observed that NBS1 mRNA nuclear export is inhibited at 28 days (supplemental Figure 1B). Consistent with impairment of eIF4E-dependent mRNA export, cyclin D1 and NBS1 protein levels were reduced in all patients analyzed (Figure 1C). Nuclear re-entry of eIF4E was usually observed between 56 and 84 days, which generally coincided with loss of clinical response (Figure 1B, supplemental Figures 2-3).

In all patients studied, roughly 80% of cells have primarily nuclear eIF4E at baseline, consistent with previous observations1 (supplemental Figures 2-3). Relocalization of nuclear eIF4E to the cytoplasm was observed in all but one case (Figure 1B; supplemental Figures 2-3). For example at 56 days when patient 6 achieved BR, 90% of cells had primarily cytoplasmic eIF4E. By 84 days, 80% of cells had primarily nuclear eIF4E and this coincided with increased blasts (> 80%) (Figure 1B). In patients 8 and 10, cells with primarily cytoplasmic eIF4E increased by 28 days to 70% and 90% respectively, but by 56 to 84 days the number of cells with primarily cytoplasmic eIF4E decreased to 50%. At this time, there were increased blasts in both patients. In patient 11, 80% of cells had primarily cytoplasmic eIF4E by 28 days and this remained the predominant population at 56+ days when CR was confirmed. For patient 12, who received only 19 days of treatment, a similar redistribution of eIF4E to the cytoplasm was observed. Finally for patient 9, eIF4E was not relocalized to the cytoplasm, eIF4E RNA levels were not lowered by treatment, and there was rapidly progressive disease (supplemental Figures 2-3, supplemental Table 1). We conclude that reduction of eIF4E levels and relocalization of eIF4E from the nucleus to cytoplasm are associated with clinical benefit.

Discussion

Our studies show that ribavirin effectively targets eIF4E in humans and suggest that the nuclear localization of eIF4E, and thus its mRNA export function, contributes significantly to its transformation capacity in humans. Several proteins modulate the localization of eIF4E including 4E-T, LRPPRC, and BP1.14 Future studies will enable us to understand this relocalization phenomenon. Ribavirin treatment reduced the monocytic blast subpopulations of many patients suggesting ribavirin may selectively target these cells. Ribavirin affected eIF4E levels in patients but not in cell culture. This can be explained by differences in treatment time (28 days in patients vs 24-48 hours in cells). This novel finding suggests that ribavirin could be used in place of gene therapy strategies targeting eIF4E.15-17

We show that targeting eIF4E with ribavirin in humans is clinically beneficial. Ribavirin shows significant single-agent activity in patients with poor-prognosis AML, with no significant treatment-related toxicity. Combination therapy with chemotherapeutic agents may enhance the efficacy of this therapy. Although further research is needed to confirm eIF4E as a target and ribavirin as a therapy for AML, our results suggest that ribavirin treatment (either alone, or in combination) could be clinically beneficial in the 30% of cancers characterized by elevated eIF4E.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for helpful discussions and encouragement from Serafin Piñol Roma, Claude Perreault, and Craig Jordan. We thank the staff at all 3 sites and also the following for technical expertise: Tina Haliotis, Louis Gaboury, Daniele Gagné, and Christian Charbonneau. We thank Boba Orolicki for technical assistance.

The Institute for Research in Immunology and Cancer receives infrastructure support from the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé Quebec (FRSQ) and a Canadian Institutes of Health Research multiresource grant. This project was funded by a Translational Research Program grant from the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society to K.L.B.B. K.L.B.B. holds a Canada Research Chair, and W.H.M. is a Chercheur National of the FRSQ.

This work is dedicated to the fond memory of Nathalie Beslu.

Authorship

Contribution: S.A. contributed to study design, wrote the clinical protocol, followed patients, collected bone marrow aspirates, analyzed and interpreted data, and contributed to writing the paper; B.C., A.A., and N.B. conducted and analyzed experiments and edited the paper; E.C. and C.R. coordinated all activities from multiple sites, assisted with the protocol, and edited the paper; S.C. followed patients at JGH; B.L. (McMaster) and D.-C.R. (Hôpital Maisonneuve Rosemont) saw patients at their sites, and contributed to design, interpretation, and paper preparation; W.H.M. contributed to study design, analyzed data, and edited the paper; K.L.B.B. came up with the concept of targeting eIF4E with ribavirin in cancer, contributed to trial design, analyzed data, and contributed to paper writing.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: K.L.B.B. holds an equity position in Translational Therapeutics. S.A., B.C., E.C., C.R., A.A., N.B., W.H.M., S.C., B.L., and D.-C.R. declare no competing financial interests.

Nathalie Beslu died on October 14, 2008.

Correspondence: Katherine L. B. Borden, Institute for Research in Immunology and Cancer, Université de Montréal, C.P. 6128 succ Centre-ville, Montréal, QC, H3C 3J7; e-mail: katherine.borden@umontreal.ca; or Wilson Miller, Jewish General Hospital, McGill University, 3755 Côte Ste-Catherine Rd, Montréal, QC, H3T 1E2, Canada; e-mail: wmiller@ldi.jgh.mcgill.ca.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal