Abstract

Human immunodeficiency virus-1 subtypes A and C differ in the highly conserved Gag-TL9 epitope at a single amino acid position. Similarly, the TL9 presenting human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I molecules B42 and B81 differ only at 6 amino acid positions. Here, we addressed the influence of such minor viral and host genetic variation on the TL9-specific CD8 T-cell response. The clonotypic characteristics of CD8 T-cell populations elicited by subtype A or subtype C were distinct, and these responses differed substantially with respect to the recognition and selection of TL9 variants. Irrespective of the presenting HLA class I molecule, CD8 T-cell responses elicited by subtype C exhibited largely comparable TL9 variant cross-recognition properties, expressed T-cell receptors that used almost exclusively the TRBV 12-3 gene, and selected for predictable patterns of viral variation within TL9. In contrast, subtype A elicited TL9-specific CD8 T-cell populations with completely different, more diverse TCRBV genes and did not select for viral variants. Moreover, TL9 variant cross-recognition properties were extensive in B81+ subjects but limited in B42+ subjects. Thus, minor viral and host genetic polymorphisms can dramatically alter the immunologic and virologic outcome of an epitope-specific CD8 T-cell response.

Introduction

The genetic diversity of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) presents a major obstacle for vaccine design; and despite much effort, the induction of a broadly cross-reactive adaptive T-cell response with potent antiviral efficiency remains an elusive goal.1-3 Indeed, HIV-1 is among the most genetically diverse human viruses, which is partly reflected by the existence of 9 genetically distinct subtypes (A-D, F-H, J, and K) within HIV group M, the causative agent for the global HIV-1 pandemic.4 Geographic regions differ in predominating subtypes, with subtypes A and C among those that have spread most successfully within human populations.4 Subtypes differ from one another by up to 30% of amino acid residues within single proteins; and although virus isolates from the same subtype can differ considerably, they are genetically more closely related to each other than to isolates from different subtypes. This is evidence in subtype-specific amino acid positions within the proteome that consistently differ between subtypes. The immunodominant p24 Gag epitope TPQDLNTML (TL9; residues 180-188) contains an example of a subtype-specific amino acid substitution. The TL9 sequence is highly conserved within subtypes B, C, D, F, G, J, and K and is among the most frequently recognized epitopes in HIV-infected subjects from most sub-Saharan African regions.5-7 However, subtype A and the related circulating recombinant forms CRF01_AE and CRF02_AG, which are responsible for a significant fraction of the HIV pandemic, differ from other subtypes with a threonine-to-methionine substitution at position 7 of the TL9 epitope (TL9M7)

In addition to viral diversity, host genetic diversity further confounds the rational design of T cell–based vaccines. The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I gene locus is among the most polymorphic in the human genome, and even minor differences between alleles can alter the rate of progression to AIDS.8 Expressed HLA class I molecules determine viral epitope presentation to CD8 T cells, which compose one of the main effector arms of the host immune response to HIV infection. This is evidenced by several observations, including: (1) the appearance of CD8 T-cell responses is temporally associated with viremic control during acute infection9,10 ; (2) CD8 T cells can limit virus replication in vitro11 ; (3) depletion of CD8 T cells in the SIV macaque model is associated with elevated viral replication in vivo12,13 ; and (4) certain CD8 T-cell responses are consistently associated with viremic control.14-17 Furthermore, CD8 T cell–mediated immune pressure often selects for viruses with mutations in targeted epitopes.18-21 These effects govern the evolution of HIV within the host22 and, in turn, can have profound effects on pathogenesis.23 For example, in conserved regions of the capsid protein, such immune escape mutations can impair viral fitness and therefore attenuate replication rates.15,24 Thus, a detailed understanding of how epitope-specific CD8 T-cell responses impact viral evolution and biologic outcome is essential for rational vaccine design.

Although CD8 T-cell epitopes and associated patterns of viral escape within the HIV proteome are largely predictable based on the HLA class I genotype of the infected host, it is unclear whether these predictions extend to HIV-1 infections with subtypes other than B or C. In this study, we investigated TL9-specific CD8 T-cell responses restricted by HLA B42 or HLA B81, which differ at only 6 amino acid residues (ImMunoGeneTics/HLA database at http://www.ebi.ac.uk/imgt/hla/), in subjects infected with HIV-1 subtype A or subtype C to examine the impact of minor genetic polymorphisms, both within a presented immunodominant epitope and its associated restriction element, on the CD8 T cell–mediated immunity and patterns of viral escape.

Methods

Study subjects

The persons in this study were part of a larger, well-characterized high-risk cohort of female bar workers enrolled in a prospective study of HIV-1 infection in the Mbeya region of Southwest Tanzania.7,25 During the course of this study, all persons were antiretroviral-naive. HIV-1 status was determined using 2 diagnostic HIV enzyme-linked immunoassay tests (Enzygnost Anti-HIV1/2 Plus, Dade Behring; and Determine HIV 1/2, Abbott). Discordant results were resolved using a Western blot assay (Genelabs Diagnostics). The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the National Institute for Medical Research–Mbeya Medical Research Program in compliance with national guidelines and institutional policies, and informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Studies that are conducted at the National Institute for Medical Research–Mbeya Medical Research Program undergo 2 independent Institutional Review Board approvals: (1) the local ethic board at Mbeya (FWA no. 00002469) and (2) the National Ethic Board at the National Institute for Medical Research (FWA no. 00002632).

HLA genotyping

HLA class I alleles (A, B, and C) were typed by DNA sequencing using an ABI 3700 sequencer as described previously.26

Peptides

Lyophilized peptides for TL9 epitope variants (New England Biolabs) were dissolved at 10 mg/mL in high-performance liquid chromatography–grade dimethyl sulfoxide and further diluted in phosphate-buffered saline to a working concentration of 100 μg/mL. Peptide sequences were confirmed at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases protein sequencing facility.

IFN-γ ELISpots

Cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from HIV-infected subjects were recovered from frozen and rested overnight before simulations. The interferon-γ (IFN-γ) ELISpot protocol used was a modified version of that described previously.27 The final steps incorporated a 1:500 dilution of streptavidin alkaline phosphatase (Mabtech). Plates were developed using 1-step NCBIT/BCP (Pierce Biotech).

Peptide-MHC class I tetramers

Fluorochrome-labeled tetrameric pHLA B*4201 and pHLA B*8101 complexes were produced with the peptides TPQDLNTML (TL9T7) and TPQDLNMML (TL9M7) as described previously.28

Peptide stimulations for intracellular cytokine staining

Cryopreserved PBMCs recovered from frozen and resuspended at 2 × 106 cells/mL in complete RPMI media. Costimulatory antibodies (αCD28 and αCD49d; 1 μg/mL final concentration; BD Biosciences) were added to cells before splitting them into different tubes for stimulation with different TL9 peptide variants. After 2 hours, brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich) was added at 10 μg/mL final concentration and incubated for an additional 4 hours. A negative control containing PBMCs from the same person but with no added peptide was included for each sample.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

PBMCs were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline, stained with ViVid (Invitrogen),29 and incubated in the dark for 15 minutes at 37°C with flourochrome-labeled peptide–MHC class I tetramers as described previously.30 For the simultaneous staining of subtype A (TL9M7)– and subtype C (TL9T7)–specific CD8 T cells, tetramers were premixed to avoid any bias that might arise as a function of rapid tetramer on-rates.31 Then, PBMCs were washed twice and stained for 20 minutes at room temperature in the dark with the following directly conjugated monoclonal antibodies: αCD3-Cy7APC (BD Biosciences), αCD4-PECy5.5 (Invitrogen), and αCD8–quantum dot 655 (conjugated in-house according to standard protocols; http://drmr.com/abcon/index.html). Between 140 and 10 000 live, antigen-specific CD8 T cells from each of up to 3 different populations were then sorted directly into RNAlater (Ambion) using a FACSAria flow cytometer (BD Immunocytometry Systems) and stored at −80°C. Electronic compensation was conducted with antibody capture beads (BD Biosciences) stained separately. Data analysis was performed using FlowJo Version 8.2 software (TreeStar).

Molecular analysis of expressed TCR gene products

mRNA from sorted populations of antigen-specific CD8 T cells was extracted using the Oligotex kit (QIAGEN) and subjected to a nonnested, template-switch anchored reverse-transcribed polymerase chain reaction using a 3′ TCRB constant region primer as described previously.32,33 Amplified products were purified by gel electrophoresis, ligated into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega), cloned by transformation of competent DH5α Escherichia coli, and sequenced as described previously.28 Discounting pseudogenes and nonfunctional sequences, a minimum of 20 viable sequences per sample was generated and analyzed. Nucleotide comparisons were used to establish clonal identity using Sequencher Version 4.6 (Genecodes Inc).

HIV sequencing

HIV-1 RNA was extracted from plasma using the QIAmp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN). cDNA was synthesized using ThermoScript RT with the 3′ primer BJPOL6 (5′-TTACTTTGATAAAACCTCCAATTCCYCCTATC-3′; Invitrogen) as described previously34 ; products were amplified using the primers MSF12B (5′-AAATCTCTAGCAGTGGCGCCCGAACAG-3′)/BJPOL6 and nested with GAG763 (5′-TGACTAGCGGAGGCTAGAAGGAGAGA-3′)/JL80 (5′-TAATACTGTATCATCTGCTCCTGT-3′). The polymerase chain reaction mixtures and cycling conditions were described previously.35 Amplicons were purified using the Microcon centrifugal filter YM-50 (Millipore) and sequenced with an ABI3100 capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems). DNA sequences were assembled using Sequencher Version 4.2.2 (Genecodes) and aligned with reference sequences of HIV-1 subtypes and circulating recombinant forms. Phylogenetic analysis was performed with SEQBOOT, DNADIST, NEIGHBOR, and CONSENSE from Version 3.4 of the PHYLIP package. A neighbor joining tree was constructed with Treetool from the sequences of interest and reference strains. Bootstrap values of 70% or greater and in neighbor joining trees were used to confirm subtype assignments. For the purposes of our analysis, we list recombinant strains by their subtype assignment within the TL9 epitope region. The subtype D sequence of subject H122 was listed as a subtype C because subtypes D and C are indistinguishable in the TL9 region.

GenBank accession numbers

Results

The TL9-specific CD8 T-cell response induces viral variants in subtype C but not subtype A

The most conclusive evidence for CD8 T cell–mediated immune pressure during HIV infection comes from the selection of variant viruses that carry mutations in or around the targeted epitopes. To estimate the immune pressure exerted by the TL9-specific CD8 T-cell response to either subtype A or subtype C infection, we analyzed 122 East African subtype A and subtype C epitope sequences in relation to the expression of HLA B42 and HLA B81 (Table 1).

HLA class I–associated polymorphisms within the TL9 epitope are observed in subtype C but not in subtype A viruses

| . | Subtype C . | Subtype A . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence . | n . | % . | Sequence . | n . | % . | |

| B42− | TPQDLNTML | 36 | 90.0 | TPQDLNMML | 30 | 75.0 |

| B81− | ------S-- | 2 | 5.0 | I-------- | 2 | 5 |

| --S---S-- | 1 | 2.5 | --G------ | 2 | 5 | |

| --A------ | 1 | 2.5 | ------V-- | 2 | 5 | |

| ------T-- | 1 | 2.5 | ||||

| --S------ | 1 | 2.5 | ||||

| --H------ | 1 | 2.5 | ||||

| I-H------ | 1 | 2.5 | ||||

| B81+ | TPQDLNTML | 1 | 14.3 | TPQDLNMML | 8 | 88.9 |

| ------S-- | 4 | 57.1 | --G------ | 1 | 11.1 | |

| --S---S-- | 2 | 28.6 | ||||

| B42+ | TPQDLNTML | 6 | 42.9 | TPQDLNMML | 8 | 66.7 |

| --T------ | 4 | 28.6 | ------T-- | 2 | 16.7 | |

| --S---S-- | 2 | 14.3 | --S------ | 1 | 8.3 | |

| --A------ | 1 | 7.1 | I-------- | 1 | 8.3 | |

| --G------ | 1 | 7.1 | ||||

| . | Subtype C . | Subtype A . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence . | n . | % . | Sequence . | n . | % . | |

| B42− | TPQDLNTML | 36 | 90.0 | TPQDLNMML | 30 | 75.0 |

| B81− | ------S-- | 2 | 5.0 | I-------- | 2 | 5 |

| --S---S-- | 1 | 2.5 | --G------ | 2 | 5 | |

| --A------ | 1 | 2.5 | ------V-- | 2 | 5 | |

| ------T-- | 1 | 2.5 | ||||

| --S------ | 1 | 2.5 | ||||

| --H------ | 1 | 2.5 | ||||

| I-H------ | 1 | 2.5 | ||||

| B81+ | TPQDLNTML | 1 | 14.3 | TPQDLNMML | 8 | 88.9 |

| ------S-- | 4 | 57.1 | --G------ | 1 | 11.1 | |

| --S---S-- | 2 | 28.6 | ||||

| B42+ | TPQDLNTML | 6 | 42.9 | TPQDLNMML | 8 | 66.7 |

| --T------ | 4 | 28.6 | ------T-- | 2 | 16.7 | |

| --S---S-- | 2 | 14.3 | --S------ | 1 | 8.3 | |

| --A------ | 1 | 7.1 | I-------- | 1 | 8.3 | |

| --G------ | 1 | 7.1 | ||||

Shown are plasma virus TL9 epitope sequences isolated from 122 HIV-infected East Africans from Kenya and Tanzania. The TL9 epitope sequences are grouped into either subtype A or subtype C and then further subdivided according to the presence or absence of the TL9-presenting HLA class I molecules B42 and B81 in the infected host.

The TL9 epitope in subtype C viruses was highly conserved in the absence of B42 and B81 alleles, with 90% (n = 36) matching the consensus epitope sequence TL9T7. Subtype A viruses were somewhat less homogeneous, with 75% matching the subtype-specific consensus sequence TL9M7 (n = 30). Taken together, these data indicate that sequence variation within the TL9 epitope is limited in subtype C and subtype A viruses in the absence of HLA-associated selection pressure. The infrequent variation from the consensus sequence in the absence of B42 and B81 occurred at positions 3 and 7 for both subtype A and subtype C epitopes; in addition, variants were observed at position 1 in subtype A epitope. These data suggest that variation can occur at positions 1, 3, and 7 of the TL9 epitope without dramatic negative effects on viral fitness.

In subtype C infection, the presence of B42 or B81 strongly influenced TL9 sequences. Viruses with a threonine-to-serine substitution at position 7 (TL9S7) were predominantly selected in the presence of B81. This substitution was observed in 6 of 7 subjects (P < .001, Fisher exact test). In 2 of these subjects, a second substitution at position 3 (TL9S3S7) was observed in association with the coexpression of a second TL9 presenting allele (B07 or B42). Furthermore, 5 of 6 TL9S7 variant viruses also had further substitutions upstream (E to D at residue 177) or downstream (T to I/A at residue 190) of the TL9 epitope. In contrast, the presence of B42 was associated with the selection of viruses with substitutions at epitope position 3. In 8 of 14 subjects (P < .001, Fisher exact test), diverse mutations at position 3 were observed with the consensus glutamine being replaced by threonine (TL9T3, n = 4), glycine (n = 1), alanine (n = 1), or serine in combination with a second serine at position 7 (TL9S3S7, n = 2). The latter TL9S3S7 variant viruses were isolated from subjects who coexpressed either B53 or B81. There was no evidence that other TL9 presenting HLA alleles, such as B07 and B53, influenced TL9 sequences when expressed in isolation (data not shown). In line with previous observations,37 these results demonstrate that the TL9T7-specific CD8 T-cell response exerts immune pressure in subtype C infections regardless of the presenting HLA allele (ie, B42 or B81), but that the character of the immune pressure differs depending on the presenting HLA allele.

In stark contrast to subtype C infections, neither B42 nor B81 was associated with viral variants in subtype A viruses. In 8 of 9 B81+ subjects and 8 of 12 B42+ subjects, the subtype A consensus sequence TL9M7 was observed. Similarly, the subtype A TL9 consensus sequence was observed in 9 of 11 subjects with B53, which frequently restricts TL9M7-specific CD8 T-cell responses.5 Thus, subtype A TL9 epitope sequences failed to show evidence of immune-driven viral variation in the presence of B42 or B81, despite the presence of mutations at positions 3 and 7 in the absence of these alleles comparable with those observed in subtype C viruses.

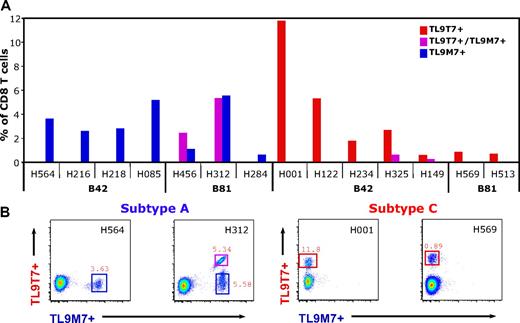

High frequencies of TL9-specific CD8 T cells in subtype A and subtype C infections

The TL9 epitope is the most frequently recognized Gag epitope in subjects with chronic HIV infection from the Mbeya region, Southwest Tanzania.7 To characterize TL9-specific CD8 T-cell responses in subtype A and subtype C infection in greater detail, the following subtype-specific HLA class I tetramers for B42 and B81 were generated: (1) B42/TL9T7 and B81/TL9T7 for subtype C; and (2) B42/TL9M7 and B81/TL9M7 for subtype A. We first analyzed the frequency of TL9-specific CD8 T cells using these subtype-specific tetramers in combination. As shown in Figure 1, high frequencies of TL9-specific CD8 T cells were detected directly ex vivo regardless of the infecting subtype and the presenting HLA class I molecule. Distinct TL9-specific CD8 T-cell populations that cross-recognized the nonautologous subtype consensus epitope were detected in 2 of 3 B81+ subjects infected with subtype A and 2 of 5 B42+ subjects infected with subtype C.

HIV subtype A and subtype C infections induce high frequencies of TL9-specific CD8 T cells in subjects expressing HLA B42 or HLA B81. (A) The fraction of CD8 T cells that bound autologous or both subtype-specific TL9/HLA class I tetramers (y-axis) in relation to the infecting subtype and the presenting HLA class I molecule (x-axis). (B) Representative CD8 T cell–gated dot plots showing HLA class I–matched subtype-specific tetramer staining of PBMCs from B42+ or B81+ subjects infected with either subtype A (left panels) or subtype C (right panels).

HIV subtype A and subtype C infections induce high frequencies of TL9-specific CD8 T cells in subjects expressing HLA B42 or HLA B81. (A) The fraction of CD8 T cells that bound autologous or both subtype-specific TL9/HLA class I tetramers (y-axis) in relation to the infecting subtype and the presenting HLA class I molecule (x-axis). (B) Representative CD8 T cell–gated dot plots showing HLA class I–matched subtype-specific tetramer staining of PBMCs from B42+ or B81+ subjects infected with either subtype A (left panels) or subtype C (right panels).

Regardless of the infecting subtype, tetramer-binding CD8 T cells responded to the subtype-specific TL9 consensus peptides as determined by IFN-γ production and down-modulation of the T-cell receptor (TCR, data not shown). No differences in cytokine secretion or perforin expression were observed in response to subtype A or subtype C (data not shown). Taken together, these results demonstrate that high frequencies of TL9-specific CD8 T cells are generated in vivo on infection with subtype A or subtype C viruses.

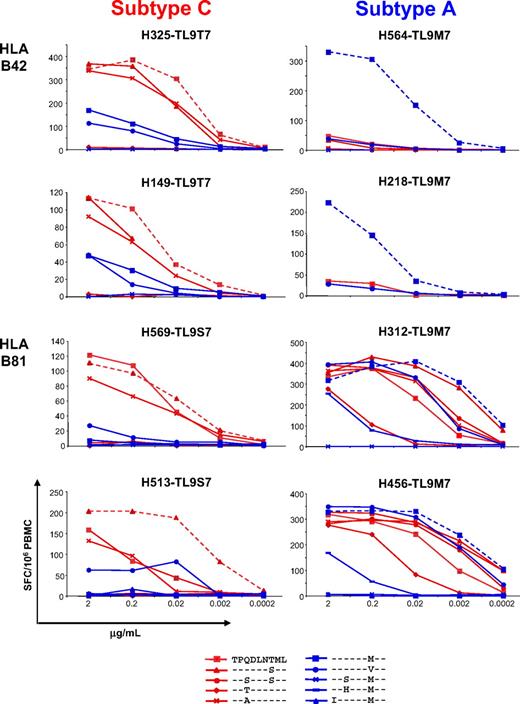

The infecting subtype affects TL9-specific variant cross-recognition

To determine why viral epitope variants occurred in subtype C, but not subtype A, infection despite the presence of CD8 T-cell responses with similar magnitudes in each case, we assessed the capacity of TL9-specific CD8 T-cell populations induced by subtype A and C infections to cross-recognize common epitope variants in an IFN-γ-ELISpot assay. Cross-recognition was studied in B42+ (n = 6) and B81+ (n = 3) subjects infected with subtype C, and in B42+ (n = 4) and B81+ (n = 3) subjects infected with subtype A. Strikingly, recognition of different TL9 epitope variants was markedly different between subjects infected with subtype A and subtype C. Data for 2 representative subjects from each group are shown in Figure 2; an extended dataset is shown in supplemental Figure 1 (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Cross-recognition of TL9 epitope variants is largely determined by the infecting subtype and the presenting HLA class I molecule. Peptide recognition was assessed in IFN-γ ELISpot assays across a range of concentrations as indicated. Individual peptide sequences are identified in the key; autologous sequences are listed with the subject code. Data from 2 representative subjects in each of the 4 groups, defined by the infecting HIV subtype and the presenting HLA class I molecule, are shown; the entire dataset is shown in supplemental Figure 1. Subtype A– and subtype C–specific TL9 epitope variants are represented in blue and red, respectively; responses to autologous TL9 sequences are shown as dashed lines in each case.

Cross-recognition of TL9 epitope variants is largely determined by the infecting subtype and the presenting HLA class I molecule. Peptide recognition was assessed in IFN-γ ELISpot assays across a range of concentrations as indicated. Individual peptide sequences are identified in the key; autologous sequences are listed with the subject code. Data from 2 representative subjects in each of the 4 groups, defined by the infecting HIV subtype and the presenting HLA class I molecule, are shown; the entire dataset is shown in supplemental Figure 1. Subtype A– and subtype C–specific TL9 epitope variants are represented in blue and red, respectively; responses to autologous TL9 sequences are shown as dashed lines in each case.

Subtype C infections were associated with a relatively consistent pattern of cross-reactivity; indeed, the same TL9 variants were recognized regardless of the presenting HLA class I molecule. The subtype C consensus TL9T7 and the variants TL9S7 and TL9A3 were recognized well in the majority of subjects. In addition, TL9M7, the subtype A consensus sequence and/or TL9V7 were often weakly recognized by these persons. The autologous virus sequence was typically recognized most efficiently and elicited the greatest response magnitude, even in subjects infected with subtype C particular TL9 variant viruses that were not cross-recognized by subjects infected with a wild-type virus (TL9T3, TL9S3S7, data not shown). These data suggest that the TL9-specific CD8 T-cell response actively adapts to the emergence of such epitope mutations or that recognition is maintained as these epitope mutations emerge.38,39

Subtype A viruses induced TL9-specific CD8 T-cell populations with a completely different pattern of epitope variant cross-reactivity. In addition, the presenting HLA class I molecule had a dramatic impact on epitope cross-recognition properties. TL9 variant cross-recognition was very limited in B42+ subjects but extensive in B81+ subjects. Indeed, 3 of 4 B42+ subjects almost exclusively recognized the autologous subtype A consensus sequence with little cross-recognition of any other TL9 epitope variant. In contrast, 3 of 3 B81+ subjects exhibited strong and broad cross-recognition of many different TL9 variants.

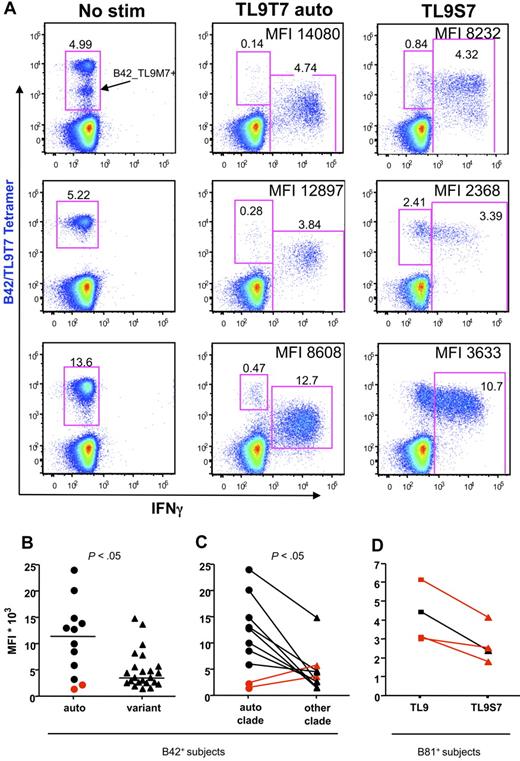

Epitope variant recognition is associated with decreased cellular IFN-γ production

In subjects infected with a virus whose TL9 sequence matched the subtype consensus, recognition of epitope variants was typically associated with substantial decreases in the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of intracellular IFN-γ staining and reduced downmodulation of the TCR on IFN-γ+ cells (P < .05) after peptide stimulation for 6 hours, even with functional responses of comparable magnitude (Figure 3). In contrast, subjects infected with the subtype C TL9S7 variant form of the virus (Figure 3D highlighted in red) responded to this autologous epitope with reduced cellular IFN-γ production relative to the subtype C consensus, thereby suggesting that this epitope mutation might reduce antiviral immune pressure. Thus, recognition of autologous TL9 epitope “escape” variants is typically associated with decreased effector functions in vitro.38 Furthermore, despite the apparent capacity to adapt to viral epitope mutations, variant-specific CD8 T-cell responses appeared to be greatly attenuated, a phenomenon reminiscent of the original antigenic sin.40,41

TL9 epitope variant recognition is associated with reduced IFN-γ production and attenuated TCR down-regulation. (A) Representative CD8 T cell–gated dot plots from subtype C–infected B42+ subjects (from top to bottom, H325, H234, H122) showing TL9T7/B42 tetramer staining (y-axis) versus intracellular IFN-γ production (x-axis) after stimulation with TL9T7 or the TL9S7 variant; the MFI of IFN-γ+ cells is indicated. The intermediate tetramer-positive population indicated in the top left panel is a cross-reactive population that also binds the TL9M7/B42 tetramer. (B) Comparison of IFN-γ MFI values in B42+ samples stimulated with autologous peptide or different TL9 variant peptides. Horizontal bars represent median values. (C) Comparison of IFN-γ MFI values in B42+ samples stimulated with autologous or nonautologous subtype-specific peptides. Two subjects with an “escaped” autologous mutant epitope (TL9T3) are highlighted in red. (D) Comparison of IFN-γ MFI values in B81+ samples infected with subtype C stimulated with the subtype C consensus TL9T7 or with the variant peptide TL9S7. Three subjects with an autologous TL9S7 mutant epitope are highlighted in red. Statistical analysis was performed using the 2-tailed Mann-Whitney test (B) or the 2-tailed Wilcoxon test (C).

TL9 epitope variant recognition is associated with reduced IFN-γ production and attenuated TCR down-regulation. (A) Representative CD8 T cell–gated dot plots from subtype C–infected B42+ subjects (from top to bottom, H325, H234, H122) showing TL9T7/B42 tetramer staining (y-axis) versus intracellular IFN-γ production (x-axis) after stimulation with TL9T7 or the TL9S7 variant; the MFI of IFN-γ+ cells is indicated. The intermediate tetramer-positive population indicated in the top left panel is a cross-reactive population that also binds the TL9M7/B42 tetramer. (B) Comparison of IFN-γ MFI values in B42+ samples stimulated with autologous peptide or different TL9 variant peptides. Horizontal bars represent median values. (C) Comparison of IFN-γ MFI values in B42+ samples stimulated with autologous or nonautologous subtype-specific peptides. Two subjects with an “escaped” autologous mutant epitope (TL9T3) are highlighted in red. (D) Comparison of IFN-γ MFI values in B81+ samples infected with subtype C stimulated with the subtype C consensus TL9T7 or with the variant peptide TL9S7. Three subjects with an autologous TL9S7 mutant epitope are highlighted in red. Statistical analysis was performed using the 2-tailed Mann-Whitney test (B) or the 2-tailed Wilcoxon test (C).

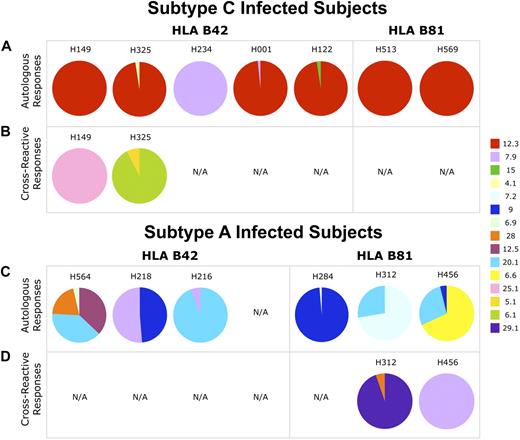

Subtype A and subtype C induce different CD8 T-cell clonotypes

To explore whether differences in T-cell clonality might explain the observed subtype-specific disparities in cross-recognition and the emergence of viral variants, we next analyzed the clonotypic composition of TL9-specific CD8 T cells. For B42+ and B81+ subjects, TL9T7 and TL9M7 tetramers were labeled with different fluorochromes and used together in premixed form to enable the simultaneous identification and flow cytometric sorting of live antigen-specific CD8 T cells; molecular analysis of TCR gene expression within the sorted populations was conducted as described previously.32,33 Overall, the TL9-specific CD8 T-cell populations were remarkably oligoclonal, composing a mean of 3.2 clonotypes per repertoire (range, 1-6 clonotypes). Interestingly, this did not differ according to the restricting HLA class I molecule, despite the impaired CD8 binding properties of B81 that might be expected to limit clonotypic recruitment.28 Furthermore, these TL9-specific repertoires were, in general, heavily skewed toward dominant CD8 T-cell clonotypes; in 10 of 17 subjects, TL9-specific CD8 T-cell populations contained single clonotypes that represented more than 90% of the entire repertoire. No obvious TCRB CDR3 amino acid motifs were observed within persons, within HLA-specific groups, or within groups defined by their infecting subtype (supplemental Figure 1).

In subtype C infections, CD8 T cells that bound only the corresponding HLA class I–matched subtype C tetramer were usually dominated by clonotypes with characteristic TCRs. Thus, clonotypes that used TRBV 12-3 gene dominated in 6 of 7 subtype C–infected subjects (Figure 4A). Strikingly, despite the solitary amino acid difference in the presented epitope, CD8 T-cell populations identified with the subtype A tetramers exhibited a completely different TCR repertoire with more diverse TCRBV and TCRBJ usage and no preferential gene expression patterns between persons (Figure 4C).

TCRBV usage in TL9-specific CD8 T-cell populations differs according to the infecting HIV-1 subtype. Each pie chart shows the relative TCRBV usage in TL9-specific CD8 T-cell populations from persons infected with subtype C (A-B) and subtype A (C-D). The color code for the different TRBV gene fragments (ImMunoGeneTics nomenclature) is shown on the right. The top panels (A,C) represent CD8 T-cell populations identified with the autologous subtype-specific tetramer only; the bottom panels (B,D) represent cross-reactive CD8 T-cell populations. N/A indicates not available (population not detected). Full clonotypic sequence information and tetramer binding patterns are shown in supplemental Figure 1.

TCRBV usage in TL9-specific CD8 T-cell populations differs according to the infecting HIV-1 subtype. Each pie chart shows the relative TCRBV usage in TL9-specific CD8 T-cell populations from persons infected with subtype C (A-B) and subtype A (C-D). The color code for the different TRBV gene fragments (ImMunoGeneTics nomenclature) is shown on the right. The top panels (A,C) represent CD8 T-cell populations identified with the autologous subtype-specific tetramer only; the bottom panels (B,D) represent cross-reactive CD8 T-cell populations. N/A indicates not available (population not detected). Full clonotypic sequence information and tetramer binding patterns are shown in supplemental Figure 1.

Interestingly, in 2 subtype C–infected B42+ subjects (H325 and H149), a distinct subtype A–specific cross-reactive CD8 T-cell population was found. Although these appear to be single tetramer-positive in supplemental Figure 1, we could detect simultaneous binding of both tetramers on CD8+ T cells from donors 325 and 149 by changing the tetramer concentrations (data not shown). In addition, only these distinct cross-reactive populations responded to stimulation with the TL9T7 and TL9M7 epitopes by producing IFN-γ, did not use the TRBV 12-3 gene (Figure 4B), and, furthermore, did not use any other TRBV genes that were expressed in subtype A–induced CD8 T-cell responses (Figure 4C). In contrast, the CD8 T-cell populations dominated by TCRBV 12-3 that bound poorly, if at all, to the TL9M7 tetramer did not respond functionally to TL9M7 when stimulated under identical conditions (data not shown). Cross-reactive populations of CD8 T cells that bound to both HLA class I–matched subtype-specific tetramers were also found in 2 of 3 B81+ subjects infected with subtype A (H312 and H456). Similarly, these cross-reactive CD8 T-cell populations did not express TRBV 12-3 (Figure 4D) and responded well to stimulation with either the autologous or heterologous peptide epitope (data not shown). The methodologic validity of tetramer competition assays for the detection of cross-reactive clonotypes was further confirmed in an additional subject (supplemental Figure 2).

Discussion

The primary aim of any vaccine strategy is to generate an effective and specific immune response. In the case of HIV infection, this goal has remained elusive partly because of the pervasive problems of both host and viral genetic diversity.1-3,42 The predominance of subtype A and subtype C infections, together with the high prevalence of HLA B42 and HLA B81 alleles, within the studied East African cohort enabled us to investigate the interplay between these variables in the context of CD8 T-cell responses to the immunodominant HIV-derived p24 Gag epitope TL9 (residues 180-188). Thus, TL9 differs at only a single residue between subtype A (M7) and subtype C (T7). The presenting molecules HLA B42 and HLA B81 differ at 6 amino acid residues: 5 of these are located within the α2 helix (positions 140-180) and could therefore impact TCR binding. These differences exemplify subtype-specific and host-related nuances that apply to other epitope-specific CD8 T-cell responses.7 The principal finding of the current analysis was that even such minor differences in the host HLA-presenting platform or the bound viral peptide epitope can profoundly affect the nature of the mobilized antigen-specific CD8 T-cell population. In turn, these effects determine the impact of the immune system on the viral quasi-species with consequences for the biologic outcome of infection.

The TL9 epitope, whether derived from subtype A or subtype C, was highly immunogenic in both B42+ and B81+ subjects from the Mbeya region, Southwest Tanzania (Figure 1); this is consistent with previous studies.5-7,37 However, substantial differences, summarized in Table 2, were apparent in the quality of the elicited TL9-specific CD8 T-cell responses. Thus, in subjects infected with subtype C, TL9-specific CD8 T cells were characterized by TRBV 12-3 gene usage and typically cross-recognized the same 3 subtype-specific variants (Figures 2,3, supplemental Figure 1); these features were associated with viral variation in the TL9 epitope (Table 1) and occurred largely irrespective of the presenting HLA class I molecule. Previous similar observations in a South African cohort confirm the general uniformity of TL9-specific CD8 T-cell responses in the context of subtype C infection.37 In contrast, different patterns of clonotype usage, variant cross-recognition, and viral variation within the targeted TL9 epitope were apparent in subjects with subtype A infection (Table 1; Figures 2,4, supplemental Figure 1). Hence, the preferential usage of single TRBV genes that characterized subtype C TL9-specific CD8 T-cell populations was notably absent in subjects infected with subtype A. Furthermore, the host genetic background exerted a marked effect on the nature of the elicited TL9-specific CD8 T-cell response in the context of subtype A infection. In B81+ subjects, broad cross-recognition of multiple TL9 variants occurred at high levels of functional sensitivity; however, only limited cross-recognition was apparent in B42+ subjects. These findings, which probably reflect structural features unique to the TL9M7 antigen at the TCR interface, are reminiscent of a previous study that reported associations between host HLA class I genetic polymorphisms and differences in the nature of an individual epitope-specific CD8 T-cell response.43 Interestingly, very limited viral variation was observed in subjects infected with subtype A regardless of the presenting HLA class I molecule. Thus, HLA-associated viral polymorphisms were largely confined to subtype C infections, despite similar intersubtype variability in B42−/B81− subjects.

Summary of results

| Infecting subtype . | Epitope consensus sequence . | Presenting HLA class 1 allele . | Clonality of TL9-specific response . | TCR-Vβ autologous response . | TCR-Vβ cross-reactive response* . | Cross-recognition TL9 epitope variants . | Viral epitope variation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | TPQDLNTML | B42 | Almost monoclonal | Vβ 12.3 dominated | No Vβ 12.3 | (+) | Position 3 |

| C | TPQDLNTML | B81 | Oligoclonal | Vβ 12.3 dominated | Not detected | (+) | Position 7 |

| A | TPQDLNMML | B42 | Oligoclonal | Diverse | Not detected | Not detected | None |

| A | TPQDLNMML | B81 | Oligoclonal | Diverse | Diverse | (+++) | None |

| Infecting subtype . | Epitope consensus sequence . | Presenting HLA class 1 allele . | Clonality of TL9-specific response . | TCR-Vβ autologous response . | TCR-Vβ cross-reactive response* . | Cross-recognition TL9 epitope variants . | Viral epitope variation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | TPQDLNTML | B42 | Almost monoclonal | Vβ 12.3 dominated | No Vβ 12.3 | (+) | Position 3 |

| C | TPQDLNTML | B81 | Oligoclonal | Vβ 12.3 dominated | Not detected | (+) | Position 7 |

| A | TPQDLNMML | B42 | Oligoclonal | Diverse | Not detected | Not detected | None |

| A | TPQDLNMML | B81 | Oligoclonal | Diverse | Diverse | (+++) | None |

When detected, cross-reactive population to heterologous subtype consensus epitope sequence.

Several studies have suggested that variant cross-recognition, whether mediated by a diverse clonotypic repertoire or the properties of individual constituent clonotypes, can limit viral escape routes.44 Thus, the observation that subtype C infections are associated with substantial HLA-associated interepitope variation despite the presence of potent and cross-reactive CD8 T-cell responses is somewhat counterintuitive. Similarly, the absence of immune-mediated variation in B42+ subjects infected with subtype A is equally surprising given the paucity of TL9 variant recognition and the limited clonotypic diversity within individual CD8 T-cell populations.32 There are several possible explanations for this conundrum. First, TL9 variant-specific responses might be less potent in terms of efficacy such that the mutation still confers a selection advantage on the carrier virus. Consistent with this notion, lower levels of IFN-γ production on a per-cell basis were observed in response to in vitro stimulation with the TL9S7 peptide relative to consensus in B81+ subjects infected with subtype C, even when this variant represented the autologous sequence, despite similar response magnitudes and functional sensitivities (Figures 2,3D, supplemental Figure 1). Second, interepitope mutations, either individually or in conjunction with additional extra-epitopic mutations, might be associated with impaired antigen processing.45,46 Indeed, extra-epitopic mutations were observed in B81+ subjects infected with subtype C in whom the TL9S7 variant predominated; furthermore, lower frequencies of TL9-specific CD8 T cells were observed in these subjects, consistent with reduced antigen drive. In this scenario, the nature of the CD8 T-cell response is largely irrelevant because of reduced or abrogated availability of the antigen for TCR engagement. Third, the dynamics of infection between subtype A and subtype C might differ, thereby favoring the emergence of escape variants in one subtype versus the other.

In terms of vaccine design, it is notable that cross-recognition of the heterologous subtype was mediated in all cases by CD8 T-cell clonotypes that differed from those induced by the autologous subtype. For example, cross-recognition of TL9T7 by subjects infected with subtype A never involved clonotypes that expressed the TRBV 12-3 gene. Similarly, cross-recognition of TL9M7 by subjects infected with subtype C did not involve clonotypes similar to those induced by subtype A infection. Thus, despite the capacity to recognize the same epitope variant, such cross-reactive populations appear to be fundamentally different from those induced by the autologous subtype. Consistent with previous work,37,47 variant recognition in this study was associated with decreased deployment of effector functions that might compromise antiviral efficacy. Hence, it is commonly assumed that “subtype-matched” or “centralized-gene-based” vaccines will induce the most efficient T-cell responses.48,49 However, our results indicate that exceptions might exist. In B81+ subjects, for example, the cross-recognition profile of TL9-specific CD8 T-cell populations induced by subtype A suggests that such responses might block escape routes for subtype C viruses more effectively than those induced by subtype C itself and thus result in more durable immune control. In line with this hypothesis, the therapeutic potential of highly cross-reactive TCRs originally selected by “none-consensus” epitope variant was highlighted by a recent report.50 Furthermore, the importance of clonotype composition must be borne in mind, irrespective of directly measured functional parameters. For example, some highly functional CD8 T-cell populations are intrinsically flawed by limited clonotype mobilization patterns that predispose to rapid immune escape.32 Thus, a “variant-immunization” strategy is still potentially viable. However, it is important that sequence selection is based on a comprehensive approach that will enable the identification of optimal antigens, either alone or in combination, for incorporation into vaccines delivered in the setting of both host and viral heterogeneity.51

In conclusion, we have shown that minor genetic differences in viral epitopes and host restriction elements can dramatically affect CD8 T-cell immunity with profound implications for the biologic outcome of HIV infection. These findings indicate that, in addition to the identification of optimal antigens, rational vaccine design should also incorporate a comprehensive approach to epitope sequence selection guided by detailed analyses of the downstream consequences of immunization. The present data demonstrate that such an approach is feasible and provide an impetus to test such principles in larger-scale studies.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alasdair Leslie for providing the HLA B*4201 and HLA B*8101 heavy chain plasmids.

D.A.P. is a Medical Research Council (United Kingdom) Senior Clinical Fellow. Sample collection was supported by the European Commission, DG XII, INCO-DC (grant ICA-CT-2002-10048), and funding for analysis was provided by a cooperative agreement between the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine and the US Department of Defense. This research was performed as a part of the National Institutes of Health intramural program.

The views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of the US Army or the Department of Defense.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: C.G. performed research, collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript; I.S.M. performed research, clonotyped the T cells, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; S.T., G.K., and F.M. analyzed infecting HIV strains and HLA alleles; T.E.A. performed research, clonotyped the T cells, and analyzed and interpreted the data; E.G. provided analytical tools; D.R.A. sorted live epitope-specific T cells; C.P. interpreted the data; A.S. collected data; N.N. performed research; L.M. conducted the study in which the samples were collected; M.H. designed and supervised the study in which the samples were collected; D.A.P. provided analytical tools, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; D.C.D. interpreted data, wrote the manuscript, and supervised research on T-cell clonality; and R.A.K. designed and supervised research, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current address for Dr Geldmacher is Department of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine, Klinikum of University of Munich, Munich, Germany.

Correspondence: Christof Geldmacher, Institute for Tropical Medicine and Infectious Diseases, Ludwig-Maximilians University of Munich, Georgenstrasse 5, 80802 Muenchen, Germany; e-mail: geldmacher@lrz.uni-muenchen.de.