Abstract

The natural killer (NK) type of aggressive large granular lymphocytic (LGL) leukemia is a fatal illness that pursues a rapid clinical course. There are no effective therapies for this illness, and pathogenetic mechanisms remain undefined. Here we report that the survivin was highly expressed in both aggressive and chronic leukemic NK cells but not in normal NK cells. In vitro treatment of human and rat NK-LGL leukemia cells with cell-permeable, short-chain C6-ceramide (C6) in nanoliposomal formulation led to caspase-dependent apoptosis and diminished survivin protein expression, in a time- and dose-dependent manner. Importantly, systemic intravenous delivery of nanoliposomal ceramide induced complete remission in the syngeneic Fischer F344 rat model of aggressive NK-LGL leukemia. Therapeutic efficacy was associated with decreased expression of survivin in vivo. These data suggest that in vivo targeting of survivin through delivery of nanoliposomal C6-ceramide may be a promising therapeutic approach for a fatal leukemia.

Introduction

Large granular lymphocytes (LGLs) comprise 10% to 15% of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in normal adults.1 LGL can be divided into 2 major lineages, CD3− and CD3+. CD3− LGLs are natural killer (NK) cells that do not express the CD3/T-cell receptor (TCR) complex or rearrange TCR genes. In contrast, CD3+ LGL are T lymphocytes that express the CD3 surface antigen and rearrange TCR genes. Both CD3− and CD3+ LGL function as cytotoxic lymphocytes. LGL leukemia cells can be derived from either NK cells or T cells.2 Patients with NK-LGL leukemia may have a chronic or acute disease. The 2008 World Health Organization classification of mature T- and NK-cell neoplasm continues to distinguish T-cell LGL leukemia (T-LGL leukemia) from aggressive NK-cell leukemia based on their unique molecular and clinical features. Furthermore, a new provisional entity of chronic lymphoproliferative disorder of NK cells (also known as chronic NK cell lymphocytosis or chronic NK-LGL leukemia) was created to distinguish it from much more aggressive NK-cell leukemia.3 Both aggressive and chronic NK-LGL leukemia display CD3−CD56+ immunophenotype. Features of aggressive NK leukemia include high numbers of circulating NK cells, hepatosplenomegaly, and systemic symptoms.4 Aggressive NK-LGL leukemia is a fatal illness and one of the most aggressive tumors known to man, with death occurring in days to weeks after diagnosis.5 There is no known curative therapy. Therefore, there is an urgent unmet need for development of new therapeutics for this deadly disease.

Ceramide has been recognized as an antiproliferative and proapoptotic sphingolipid metabolite in vitro and in vivo.6-8 However, the use of ceramide as a therapeutic agent has been limited due to its inherent insolubility.7 Notably, liposomal-based drug delivery is a well-characterized drug delivery system for hydrophobic chemotherapeutics.9 We have developed a pegylated nanoliposomal C6-ceramide formulation, which improved the potency and efficacy of C6-ceramide and displayed therapeutic efficacy in mouse xenograft models of human breast adenocarcinoma and melanoma mouse models.8,10 Here we report that C6-ceramide, packaged in pegylated 80-nm–sized nanoliposomes, induces complete remission in a rat syngeneic model of aggressive NK-LGL leukemia. We also demonstrate that survivin, a member of the inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP) family, regulates leukemic NK cell survival via ERK/MAPK signaling and is an important cellular target of exogenous C6-ceramide.

Methods

Reagents and cell culture

Antibodies specific for phosphorylated ERK, total ERK, caspase 3, surviving, and β-actin were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. For Western blotting, 12% precasted Nupage electrophoresis gels were obtained from Invitrogen, and enhanced chemiluminescence reagent was purchased from Amersham Biosciences. P098059 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Human NKL cells (kindly provided by Dr Howard Young at National Cancer Institute [NCI]) were grown at 37°C in minimum essential media-α supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) plus 100 IU/mL interleukin-2. RNK-16 cells (kindly provided by Dr Craig Reynolds at NCI) were cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS.

Patient characteristics and preparation of PBMCs

All patients met the clinical criteria of NK-LGL leukemia with increased numbers (> 80%) of CD3−CD56+ NK cells in the peripheral blood. Patients were either diagnosed with aggressive NK-LGL leukemia (n = 3) or clinically stable chronic NK-LGL leukemia (n = 8). These patients had received no treatment at the time of sample acquisition. Peripheral blood specimens from LGL leukemia patients were obtained, and informed consents signed for sample collection in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of Penn State Hershey Cancer Institute (Hershey, PA). Buffy coats from 4 age- and gender-matched normal donors were also obtained from the blood bank of Milton S. Hershey Medical Center at College of Medicine, Penn State University. PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll-hypaque gradient separation, as described previously.11 Cell viability was determined by trypan blue exclusion assay with more than 95% viability in all the samples. NK cells from additional 11 age- and gender-matched healthy donors were isolated by a negative selection process (StemCell Technologies) as described previously.12 The purity of freshly isolated CD3−CD56+ cells (2 × 105/sample in triplicate) in each of the samples was determined by flow cytometric assay by detecting positive staining of the correlative cells surface marker for NK cells. The purity for normal purified NK cells was between 85%-90%.

Preparation of nanoliposomal ceramide

Egg phosphatidylcholine (EPC), dioleoyl phosphatidylethanolamine (DOPE), dioleoyl phosphatidylcholine (DOPC), cholesterol (CH), D-erythro-hexanoyl-sphingosine (C6-ceramide), polyethyleneglycol-450-C8-ceramide (PEG-C8), and dioleoyl-1,2-diacyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTAP) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids. NBD-C6-ceramide from where pegylated nanoliposomes (80 ± 15 nm in size) that contain 30 mol% C6-ceramide were prepared as described previously with lipids 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine, N-hexanoyl-d-erythro-sphingosine (C6), 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy polyethylene glycol-2000], and N-octanoyl-sphingosine-1-[succinyl(methoxy polyethylene glycol-750)] [PEG(750)-C8] combined in chloroform at a molar ratio of 3.75:1.75:3:0.75:0.75.7,8,10 Combined lipids were dried under nitrogen gas and resuspended in 0.9% sterile NaCl at 60°C. After rehydration, resulting solution was sonicated for 5 minutes followed by extrusion through a 100-nm polycarbonate membrane using the Avanti Mini Extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids). Control ghost nanoliposomes (non–C6-ceramide) contained a molar ratio of lipids equivalent to that of the C6-ceramide nanoliposomal formulation. The nanoliposomes were kept at 4°C in saline at a concentration of 25 mg/mL before use.

Nanoliposomal survivin siRNA–mediated protein knockdown

In these siRNA delivery experiments, we used optimized ghost cationic nanoliposomes (no ceramide), which comprise DOTAP, DOPE, and DSPE-PEG(2000) (1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[amino(polyethylene glycol)2000]) (Avanti Polar Lipids) in chloroform at a 4.75:4.75:0.5 molar ratio, to deliver siRNAs. After evaporation under nitrogen gas, the lipids were resuspended in isotonic saline at 55°C. The resulting solution was sonicated for 5 minutes and extruded through a 100-nm polycarbonate filter using an Avanti Mini Extruder. siRNA and nanoliposomes complexing occurred at a specific weight ratio of 1:10 for 24 hours. A quasielastic light scattering system (Malvern Nanosizer; Malvern Instruments) was used to measure the particle diameter of nanoliposomes ± siRNA 1 day after preparation. Previous studies have optimized nanoliposomal loading of siRNA with fluorescent, Alexa Fluor 546–tagged siRNA (Qiagen), noting that nanoliposomal encapsulation protected siRNA from FBS-induced degradation.13 Loading was considered complete when no free siRNA was evident with complex remaining in a well of a 2% agarose gel. The effectiveness of ON-TARGET plus siRNA (Dharmacon) to modify survivin levels was assessed by transfection via cationic nanoliposomes. These RNAi molecules are designed to target 4 different regions of survivin (target sequences: 5′-CAAAGGAAACCAACAAUAA-3′, 5′-GCAAAGGAAACCAACAAUA-3′, 5′-CACCGCAUCUCUACAUUCA-3′, 5′-CCACUGAGAACGAGCCAGA-3′). An appropriate negative control siRNA was chosen from the pool of RNAi Negative Control (NC) Duplex (Dharmacon) with a similar percent GC content of survivin. NKL cells (5 × 105) were plated onto 12-well plates, and nanoliposomal-survivin siRNA or nanoliposomal-control siRNA complex was added. Protein lysates were collected 72 hours later for Western blot analysis, and cell viability assays were performed.

Survivin gene expression: real-time quantitative RT-PCR

Real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed using primer sets specific for human and rat survivin, and an internal standard, 18S rRNA, in an ABI PRISM 7900 sequence detector (Applied Biosystems) as described elsewhere.14 PBMCs (5 × 106) from 3 aggressive NK-LGL leukemia patients or 8 chronic NK-LGL leukemia patients (CD3−CD56+ NK cells > 80%) and freshly purified CD3−CD56+ NK cells from 11 age- and gender- matched normal healthy controls were subjected to total RNA extraction by using TRIzoL Reagent (Invitrogen) followed the manufacturer's directions. Suspension splenocytes were isolated from spleens of NK-LGL leukemic F344 rats (n = 9) or age- and gender-matched normal rats (n = 4). NKL cells and RNK-16 cells treated with at various time points or doses of ghost or ceramide nanoliposome then total RNA was isolated. First strand cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg purified total RNA using random hexamers and MMLV reverse transcription reagents (Invitrogen) in total volume of 20 μL. A total of 1 μg cDNA was applied in a 10-μL PCR mix using a QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR kit (QIAGEN). Amplification of triplicate cDNA template samples was then performed with denaturation for 15 minutes at 95°C, followed by 40 PCR cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 15 seconds, annealing at 55°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 30 seconds. A standard curve of cycle thresholds (Ct) using serial dilutions of cDNA samples was established and used to calculate the relative abundance of the target gene between samples from patients and normal healthy controls. Values were normalized to the relative amounts of 18S mRNA, which were obtained from a similar standard curve. The changes in fluorescence of SYBR green dye in every cycle were monitored by the ABI 7900 system software and the Ct for each reaction was calculated. The relative amount of PCR products generated from each primer set was determined based on the Ct value.15 PCR analysis was performed on each cDNA sample at least twice. The following primers were used in the detection of survivin: human survivin sense, 5′- GCCACTTGTCCCAGCTTTCC-3′, antisense 5′-GTCACAATAGAGCAAAGCCACA-3′; rat survivin sense, 5′- TGAACTTCAGGTGGATGAGGAGA-3′, antisense 5′- GTCTAATCACACAGCAGTGGCAA-3′.

Survivin protein expression: mitochondria isolation and Western blot

A mitochondrial isolation kit (Pierce) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions to isolate mitochondria from aggressive NK-LGL leukemia cell lines including human NKL and rat RNK-16, or leukemic NK cells from chronic NK-LGL leukemia patients or NK cells from normal donors. Once isolated, mitochondria were lysed in buffer containing: 150mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 50mM Tris, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Lysate was then used for Western blotting with survivin antibody (Cell Signaling). Western blots were also performed and probed with survivin, p-ERK, or total ERK antibodies (Cell Signaling) using total protein lysates harvested from ghost or C6-ceramide nanoliposome- or PD098059-treated NKL or RNK-16 cells.

In vitro apoptosis and cell viability assay

Apoptosis was determined by 2-color flow cytometry with annexin V (5 μL/sample; BD Pharmingen) and 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD; 10 μL/sample) staining using 5 × 105 cells/sample. The percentage specific apoptosis was calculated using the following formula: Apoptosis (%) = (% annexin V–fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC] positive in assay well − % annexin V–FITC positive in the control well) × 100/(100 − % annexin V–FITC positive in the control well). Cell viability was performed using CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution assay kit (Promega). The relative viable cell number was determined by reading the plates at 490-nm wavelength in Synergy HT Multi-Detection Microplate Reader (Bio-TEK).

Confocal studies

To verify accumulation of C6-ceramide into RNK16 cells, we formulated a nanoliposomal C6-ceramide vesicle with 10 mol% NBD-C6 ceramide as a marker for C6. Cells were plated at 2.0 × 104/well in 8-well chamber slides and allowed to grow overnight. Nanoliposomal-NBD-C6 ceramide was treated at 25μM for a 2-hour treatment period. Cellular nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, and MitoTracker Deep Red 633 (Molecular Probes) was used as a marker for mitochondria following the manufacturer's instructions. C6-ceramide delivery and accumulation was evaluated by confocal microscopy at 63× magnification (Leica Microsystems).

Animal studies

Animal experimentation was performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Penn State College of Medicine. Male F344 rats of approximately 6 weeks of age were obtained from Charles River Laboratory. One million RNK-16 cells, an in vivo LGL leukemic cell line (provided by Dr Craig Reynolds at NCI), were intraperitoneally transplanted into each of F344 rats. Five weeks after inoculation, leukemic rats were then treated with 40 mg/kg C6-ceramide nanoliposomes 3× a week via tail vein injections over a 6-week treatment period. Rats losing 20% body weight were most likely affected by NK-LGL leukemia and were euthanized. At necropsy, spleens were dissected, weighed, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin, and sections (4 μm) were generated for histologic analysis and immunohistochemical staining. Mononuclear cells were isolated from blood, bone marrow, lymph node, and lung using Ficoll-hypaque density gradient centrifugation16 and used for quantification of CD3−CD8a+ NK cells by flow cytometry. PerCP-conjugated mouse anti–rat CD8a and FITC-conjugated mouse anti–rat CD3 were purchased from BD Pharmingen.

Detection of survivin and apoptosis in vivo

Expression of survivin was detected in the paraformaldehyde-fixed and paraffin-embedded spleen tissue sections using the survivin antibody (D-8; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) using immunohistochemical method as previously described.17 Apoptosis measurements were performed on these spleen sections using the Roche terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated nick end labeling (TUNEL) TMR Red Apoptosis kit as described previously.8

Statistical analysis

Differences among 2 treatment groups were statistically analyzed using a 2-tailed Student t test for statistical analyses. A statistically significant difference was reported with P indicated where applicable. Data are reported as the mean ± SE from at least 3 separate experiments. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves were plotted to evaluate the survival of leukemic rats; log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used to analyze the statistic difference between the ghost and ceramide nanoliposome-treated leukemic rats.

Results

Survivin mediates survival of leukemic NK cells

NK-LGL leukemic cells are resistant to Fas-induced apoptosis despite high levels of Fas and FasL expression.11,12,18 Survivin acts as a suppressor of apoptosis in a variety of malignancies.19 Knockdown of survivin by siRNA or natural compound resveratrol was found to sensitize tumor cells to TRAIL- or Fas-induced apoptosis.20-22 Survivin knockout mice were found to be more sensitive to Fas-mediated hepatic apoptosis resulting from increased activation of caspase-3.23 We found that survivin transcripts were highly expressed in leukemic NK cells from either aggressive or chronic patients with NK-LGL leukemia (Figure 1A), or from spleens of Fischer rats with aggressive NK-LGL leukemia (Figure 1B). In contrast, survivin expression was barely detectable in normal human NK cells or in splenocytes from normal Fischer rats (Figure 1A-B). Interestingly, we localized overexpression of survivin to the mitochondria in a human aggressive NK-LGL leukemia cell line NKL, which was established from the peripheral blood of a patient with aggressive NK-LGL leukemia,24 and from RNK-16, a rat aggressive NK-LGL leukemia cell line, as well as leukemic NK cells from patients with chronic NK-LGL leukemia. In contrast, survivin was undetectable in mitochondria from purified normal human NK cells (Figure 1C). These data suggest a role for survivin in inhibition of mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis in leukemic NK cells. Moreover, efficient knockdown of survivin (Figure 1D inset) resulted in 80% cell death of NKL cells (Figure 1D). Importantly, these data also demonstrate the feasibility of using cationic nanoliposome as a delivery system for siRNA into notoriously difficult to transfect NK cells for the purpose of analyzing apoptotic-signaling pathways.

Role of survivin in leukemic NK cell survival. (A) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed to measure levels of survivin mRNA in PBMCs from NK-LGL leukemia patients (CD3−CD56+ > 80%) or purified NK cells isolated from normal donors. Each circle represents an individual purified NK sample. cDNA samples were diluted 1:100 for 18S expression. ***P < .0005 indicates leukemic NK cells versus normal NK cells (Mann-Whitney test). (B) Suspension splenocytes were isolated from spleens of NK-LGL leukemic F344 rats or age- and gender-matched normal rats. RNAs were harvested from these cells, and quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed to measure levels of survivin mRNA. cDNA samples were diluted 1:100 for 18S expression. **P < .005 indicates leukemic NK cells versus normal NK cells (Mann-Whitney test). (C) Mitochondria were isolated from human aggressive NK-LGL leukemia cell line NKL or rat aggressive NK-LGL leukemia cell line RNK-16, or pooled enriched NK cells (CD3−CD56+ 80%-95%) from 5 normal human donors, or 4 individual patients with chronic NK-LGL leukemia (CD3−CD56+ cells > 80%), then resolved in the sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel loading buffer in a boiling water bath for 5 minutes. Western blot analysis was performed for detection of survivin. Cox IV, a mitochondria marker, was used as loading control. (D) NKL cells were transfected with 10 μg control siRNA or human survivin ON-TARGET plus SMARTpool siRNA (Dharmacon) per 5 × 105 cells, each complexed within cationic nanoliposomes, then MTT assay was performed 72 hours after transfection. **P < .005 indicate significant difference in cell viability of survivin siRNA-transfected cells compared with control siRNA-transfected cells (Student t test). Inset, Western blot analysis was performed for survivin in the control siRNA or survivin siRNA-transfected NKL cells 72 hours after transfection. The equal loading of protein was confirmed by probing with glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Role of survivin in leukemic NK cell survival. (A) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed to measure levels of survivin mRNA in PBMCs from NK-LGL leukemia patients (CD3−CD56+ > 80%) or purified NK cells isolated from normal donors. Each circle represents an individual purified NK sample. cDNA samples were diluted 1:100 for 18S expression. ***P < .0005 indicates leukemic NK cells versus normal NK cells (Mann-Whitney test). (B) Suspension splenocytes were isolated from spleens of NK-LGL leukemic F344 rats or age- and gender-matched normal rats. RNAs were harvested from these cells, and quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed to measure levels of survivin mRNA. cDNA samples were diluted 1:100 for 18S expression. **P < .005 indicates leukemic NK cells versus normal NK cells (Mann-Whitney test). (C) Mitochondria were isolated from human aggressive NK-LGL leukemia cell line NKL or rat aggressive NK-LGL leukemia cell line RNK-16, or pooled enriched NK cells (CD3−CD56+ 80%-95%) from 5 normal human donors, or 4 individual patients with chronic NK-LGL leukemia (CD3−CD56+ cells > 80%), then resolved in the sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel loading buffer in a boiling water bath for 5 minutes. Western blot analysis was performed for detection of survivin. Cox IV, a mitochondria marker, was used as loading control. (D) NKL cells were transfected with 10 μg control siRNA or human survivin ON-TARGET plus SMARTpool siRNA (Dharmacon) per 5 × 105 cells, each complexed within cationic nanoliposomes, then MTT assay was performed 72 hours after transfection. **P < .005 indicate significant difference in cell viability of survivin siRNA-transfected cells compared with control siRNA-transfected cells (Student t test). Inset, Western blot analysis was performed for survivin in the control siRNA or survivin siRNA-transfected NKL cells 72 hours after transfection. The equal loading of protein was confirmed by probing with glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

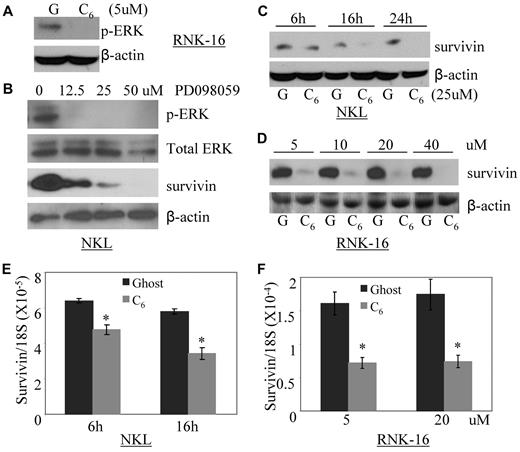

C6-ceramide down-regulates survivin expression through inhibition of ERK in leukemic NK cells and accumulates in mitochondria

Several lines of evidence have demonstrated that alterations of mitochondrial function occur as an intermediate step in transduction of ceramide signals culminating in cell death.25 Given that constitutive active ERK/MAPK is an essential survival mechanism in leukemic NK cells12 and that ceramide inhibits ERK activation in a variety of tumor cell types,26,27 we investigated whether nanoliposomal C6-ceramide treatment would inhibit activated ERK. Indeed, we showed that nanoliposomal C6-ceramide treatment can inhibit constitutive phosphorylation of ERK in RNK-16 cells (Figure 2A). Phosphorylation of ERK is an important upstream activator of survivin pathway.28,29 We found that inhibition of phosphorylation of ERK via a pharmacologic inhibitor PD098059 blocked survivin expression in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2B) and led to apoptosis in NKL cells.12 These results indicate that survivin is an important downstream target of ERK involved in the cell survival of leukemic NK cells.

Nanoliposomal-C6 ceramide inhibits the activation of ERK, which subsequently down-regulates survivin expression. (A) Western blot analysis was performed for p-ERK after treatment of RNK-16 cells with 5μM ghost or C6 nanoliposome for 18 hours. The equal loading of protein was confirmed by β-actin probing. (B) Western blot analysis was performed for p-ERK, total ERK, or survivin after treatment of NKL cells with different doses of PD098059 for 18 hours. The equal loading of protein was confirmed by β-actin probing. (C) Western blot analysis was performed for survivin after treatment of NKL cells with 25μM ghost (G) or C6 nanoliposome (C6) for 6, 16, and 24 hours. The equal loading of protein was confirmed by β-actin probing. (D) Western blot analysis was performed for survivin after treatment of RNK-16 cells with different doses of either ghost or C6 nanoliposome for 24 hours. The equal loading of protein was confirmed by β-actin probing. (E) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed to measure levels of survivin mRNA after treatment of NKL cells with 25μM ghost or C6 nanoliposome for 6 and 16 hours. *P < .05 indicates significance between ghost and C6 nanoliposome treated samples (Student t test). (F) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed to measure levels of survivin mRNA after treatment of RNK-16 cells with 5 and 20μM ghost or C6 nanoliposome for 24 hours. *P < .05 indicates significance between ghost and C6 nanoliposome-treated samples (Student t test).

Nanoliposomal-C6 ceramide inhibits the activation of ERK, which subsequently down-regulates survivin expression. (A) Western blot analysis was performed for p-ERK after treatment of RNK-16 cells with 5μM ghost or C6 nanoliposome for 18 hours. The equal loading of protein was confirmed by β-actin probing. (B) Western blot analysis was performed for p-ERK, total ERK, or survivin after treatment of NKL cells with different doses of PD098059 for 18 hours. The equal loading of protein was confirmed by β-actin probing. (C) Western blot analysis was performed for survivin after treatment of NKL cells with 25μM ghost (G) or C6 nanoliposome (C6) for 6, 16, and 24 hours. The equal loading of protein was confirmed by β-actin probing. (D) Western blot analysis was performed for survivin after treatment of RNK-16 cells with different doses of either ghost or C6 nanoliposome for 24 hours. The equal loading of protein was confirmed by β-actin probing. (E) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed to measure levels of survivin mRNA after treatment of NKL cells with 25μM ghost or C6 nanoliposome for 6 and 16 hours. *P < .05 indicates significance between ghost and C6 nanoliposome treated samples (Student t test). (F) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed to measure levels of survivin mRNA after treatment of RNK-16 cells with 5 and 20μM ghost or C6 nanoliposome for 24 hours. *P < .05 indicates significance between ghost and C6 nanoliposome-treated samples (Student t test).

To further investigate whether nanoliposomal C6-ceramide resulted in the deregulation of survivin, we treated NKL and RNK-16 with nanoliposomal C6-ceramide or nanoliposomal formulation that did not contain ceramide (ghost) and examined survivin expression. We demonstrated that C6-ceramide abolished survivin expression in a time- and dose-dependent manner in these 2 cell lines (Figure 2C-D). Interestingly, we showed that reduction of survivin by C6-ceramide was regulated at the level of transcription (Figure 2E-F) as shown previously in other experimental systems.30 These results demonstrated that exogenous C6-ceramide inhibits constitutively activated ERK, with subsequent down-regulated expression of survivin in the leukemic NK cells.

Of note, ceramide can act on the mitochondria to initiate proapoptotic effects in cancer cells via mitochondrial disruption.31 The specific delivery of ceramide to mitochondria resulted in an increased apoptotic action in comparison to nontargeted delivery.32 We also previously reported that nanoliposomal C6-ceramide was delivered and accumulated in mitochondria in mouse mammary breast adenocarcinoma cells.8 Thus, we hypothesized that exogenous nanoliposomal C6-ceramide treatment would also result in an accumulation of ceramide in the mitochondria of leukemic NK cells. Indeed, we showed localization of 25μM nanoliposomal-NBD-C6 in mitochondria of RNK-16 cells (Figure 3), signifying the accumulation of exogenous ceramide, which may be a biophysical mechanism (mitochondrial membrane collapse) in addition to the biochemical (ERK/survivin) mechanism for C6-ceramide to modulate apoptosis in leukemic NK cells.

Nanoliposomal-C6 ceramide delivery resulted in the preferential accumulation of C6 in the mitochondria in leukemic NK cells. Confocal microscopic image of 25μM nanoliposomal-NBD-C6 delivery to RNK16, a rat NK LGL leukemia cell line, showing that NBD-C6 (green) colocalized with cellular mitochondria (red); Cellular nucleus was stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue). Magnification, 63×.

Nanoliposomal-C6 ceramide delivery resulted in the preferential accumulation of C6 in the mitochondria in leukemic NK cells. Confocal microscopic image of 25μM nanoliposomal-NBD-C6 delivery to RNK16, a rat NK LGL leukemia cell line, showing that NBD-C6 (green) colocalized with cellular mitochondria (red); Cellular nucleus was stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue). Magnification, 63×.

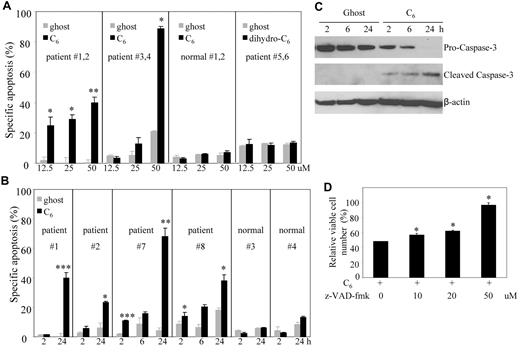

C6-ceramide induces caspase-dependent apoptotic cell death in leukemic NK cells but not normal PBMCs

We previously demonstrated the potential therapeutic utility of nanoliposomal C6-ceramide in solid tumors both in vitro and in vivo.7,8,10 We further tested this novel proprietary nanoliposomal formulation in leukemic NK LGL. Initial experiments demonstrated that nanoliposomes encapsulated with C6-ceramide but not the inactive analog dihydro-C6-ceramide33,34 displayed dose-dependent apoptotic cell death in PBMCs from either aggressive or chronic NK-LGL leukemia patients (CD3−CD56+ > 80%) but not those from normal donors (Figure 4A). Additional experiments showed that nanoliposomal C6-ceramide resulted in time-dependent apoptosis in PBMCs from both aggressive and chronic NK-LGL leukemia patients (CD3−CD56+ > 80%) but not those from normal donors (Figure 4B). We further demonstrated that the nanoliposomal-C6 induced apoptosis in patients' PBMCs via activation of caspase 3, the hallmark of caspase-dependent apoptosis (Figure 4C). Moreover, we found that death of leukemic NK cells induced by treatment with nanoliposomal-C6 can be rescued by z-VAD-fmk, a predominantly caspase-1 and caspase-3 inhibitor (Figure 4D), indicating the activation of caspase-dependent apoptotic pathway by nanoliposomal-C6.

Nanoliposomal C6 ceramide induces caspase-dependent apoptosis in leukemic NK cells but not normal PBMCs. (A) The PBMC from NK-LGL leukemia patients (CD3−CD56+ cells > 80%; patients #1 and #2 with aggressive NK-LGL leukemia, patients #3 and #4 with chronic NK-LGL leukemia) or 2 normal donors #1 and #2 were treated with 12.5, 25, and 50μM ghost or C6-ceramide nanoliposome or dihydro-C6-ceramide or ghost nanoliposome (patients #5 and #6 with chronic NK-LGL leukemia), respectively for 18 hours; then cells were assayed for apoptosis by flow cytometry. *P < .05, **P < .005 indicate significant differences of C6-treated cells versus ghost nanoliposome–treated cells (Student t test). (B) The PBMCs from individual NK-LGL leukemia patients (CD3−CD56+ cells > 80%; patients #1 and #2 with aggressive NK-LGL leukemia, and patients #7 and #8 with chronic NK-LGL leukemia) or 2 normal donors #3 and #4 were treated with 25μM C6-ceramide or ghost nanoliposome for 2, 6, and 24 hours; then cells were assayed for apoptosis by flow cytometry. *P < .05, ***P < .0005 indicate significant difference of ghost nanoliposome–treated cells (Student t test). (C) Western blot analysis was performed for caspase-3 after treatment of PBMCs from patient #8, which were treated with 25μM C6-ceramide or ghost nanoliposome for 2, 6, and 24 hours. Data are representative of 4 independent experiments on PBMCs from 4 NK-LGL leukemia patients. (D) NKL cells were exposed to 25μM C6-ceramide nanoliposome, in the absence or presence of various concentrations of z-VAD-fmk, a pan caspase inhibitor. z-VAD-fmk was added 2 hours before ceramide treatment at the indicated concentration. Cell survival was determined 18 hours later by the MTT assay. *P < .05 indicates significant differences of each dose of z-VAD-fmk–treated cells compared with z-VAD-fmk–untreated cells, respectively (Student t test).

Nanoliposomal C6 ceramide induces caspase-dependent apoptosis in leukemic NK cells but not normal PBMCs. (A) The PBMC from NK-LGL leukemia patients (CD3−CD56+ cells > 80%; patients #1 and #2 with aggressive NK-LGL leukemia, patients #3 and #4 with chronic NK-LGL leukemia) or 2 normal donors #1 and #2 were treated with 12.5, 25, and 50μM ghost or C6-ceramide nanoliposome or dihydro-C6-ceramide or ghost nanoliposome (patients #5 and #6 with chronic NK-LGL leukemia), respectively for 18 hours; then cells were assayed for apoptosis by flow cytometry. *P < .05, **P < .005 indicate significant differences of C6-treated cells versus ghost nanoliposome–treated cells (Student t test). (B) The PBMCs from individual NK-LGL leukemia patients (CD3−CD56+ cells > 80%; patients #1 and #2 with aggressive NK-LGL leukemia, and patients #7 and #8 with chronic NK-LGL leukemia) or 2 normal donors #3 and #4 were treated with 25μM C6-ceramide or ghost nanoliposome for 2, 6, and 24 hours; then cells were assayed for apoptosis by flow cytometry. *P < .05, ***P < .0005 indicate significant difference of ghost nanoliposome–treated cells (Student t test). (C) Western blot analysis was performed for caspase-3 after treatment of PBMCs from patient #8, which were treated with 25μM C6-ceramide or ghost nanoliposome for 2, 6, and 24 hours. Data are representative of 4 independent experiments on PBMCs from 4 NK-LGL leukemia patients. (D) NKL cells were exposed to 25μM C6-ceramide nanoliposome, in the absence or presence of various concentrations of z-VAD-fmk, a pan caspase inhibitor. z-VAD-fmk was added 2 hours before ceramide treatment at the indicated concentration. Cell survival was determined 18 hours later by the MTT assay. *P < .05 indicates significant differences of each dose of z-VAD-fmk–treated cells compared with z-VAD-fmk–untreated cells, respectively (Student t test).

Therapeutic efficacy of C6-ceramide nanoliposome in vivo

Fischer F344 rat LGL leukemia model has been established as an important experimental model for the study of NK-LGL leukemia progression.35,36 A panel of world authorities recently concluded that this animal model closely resembles human aggressive NK-LGL leukemia based on morphologic, functional, and clinical criteria.36 F344 rats experience a high incidence (20%-40%) of LGL leukemia in old age.37 LGL leukemia can be established in young rats within 7-12 weeks by intraperitoneal transplantation of spleen cells from aged rats with LGL leukemia.35

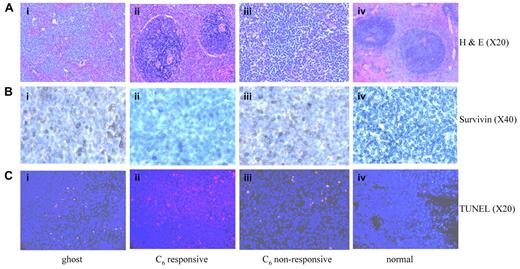

One million RNK-16, an in vivo LGL leukemic cell line was intraperitoneally transplanted into each of 6-week-old male Fischer rats. At 28 days after transplantation, the animals displayed early signs of leukemia, including weight loss, rough hair coat, and increased level of neutrophils as reported previously.35 By 35 days, circulating blasts, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and splenomegaly were observed. These leukemic rats were then injected via tail vein with 40 mg/kg of ghost or C6-ceramide nanoliposomes 3 times a week over a 6-week treatment period. Animals died within the next 1 to 3.5 weeks if untreated or if treated with ghost nanoliposome (Figure 5A). The median survival in ghost nanoliposome–treated group was 52 days compared with 61.5 days in C6-ceramide nanoliposome–treated group (Mantel-Cox test, P < .0001; Figure 5A). More importantly, 5 of 14 leukemic rats treated with nanoliposomal C6-ceramide had maintenance of normal blood counts without circulating blasts suggesting achievement of complete clinical remission (Figure 5B). To further investigate remission status, the 5 responsive animals were euthanized 2, 7, 23, 29, and 29 days after cessation of the treatment. At necropsy, we found resolution of organomegaly in these rats, representing a 3- to 10-fold reduction in the weight of these organs (Figure 5C). In addition, these rats had normal levels of LGL cells in the blood, marrow, lymph nodes, and lung (Figure 5D). Examination of spleen sections from these rats showed normal splenic histology (Figure 6A). In contrast, untreated leukemic rats or those treated with ghost nanoliposome showed leukemic LGL infiltration of the red pulp and depletion of the white pulp (Figure 6A). Our in vitro studies had determined that survivin was a cellular target of ceramide treatment in leukemic NK cells. We found that survivin expression in vivo was localized to the cytosol but not nucleus of splenic cells in leukemic rats (Figure 6B). These data suggest a role for survivin as an inhibitor of apoptosis rather than cell division in leukemic rats. We found decreased survivin expression in the spleens of the rats achieving remission; however, the survivin expression remained unchanged in C6 ceramide nonresponsive rats (Figure 6B). These data suggest that in vivo therapeutic efficacy of nanoliposomal C6-ceramide may be a consequence of survivin regulation. Indeed, we also found significant apoptosis in spleen sections from leukemic rats treated with nanoliposomal-C6 as indicated by TUNEL staining (Figure 6C). These studies demonstrate that the nanoliposomal delivery of C6-ceramide to rat LGL leukemia induces significant apoptotic death, leading to resolution of leukemic cell infiltration.

Nanoliposomal C6-ceramide liposome treatment induces complete remission in LGL leukemic rats. (A). The Kaplan-Meier survival curves for normal rats (n = 14) or leukemic rats without treatment (n = 14) or with treatment of 40 mg/kg ghost (n = 14) or C6 nanoliposome (n = 14), were plotted. Dashed arrow indicates the start of the treatment. (B) Maintenance of normal white blood counts, hemoglobin values, and platelet counts in responding leukemic rats treated with nanoliposomal C6-ceramide. Blood (200μL) from untreated leukemic rats (n = 14), leukemic rats treated with ghost nanoliposome (n = 14), C6-ceramide nanoliposome (n = 14), and normal rats (n = 14) was collected every week from tail veins of the animals and placed in EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) K2–coated tubes, then complete blood count analysis was performed. Arrow indicates the cessation of the treatment. (C) In vivo therapy with nanoliposomal C6-ceramide leads to resolution of organomegaly in responding LGL leukemic rats. The weight of spleen, liver, and thymus were measured in untreated leukemic rats (n = 14), leukemic rats treated with ghost nanoliposome (n = 14), C6-ceramide nanoliposome-responsive rats (n = 5), and normal rats (n = 14). *P < .05, ***P < .0005 indicates significance between ghost and C6-ceramide nanoliposome–treated samples (unpaired t test). D). Flow cytometry was used to identify rat LGL leukemic cells, which are CD3−CD8a+. Comparison of CD3−CD8a+ NK cells isolated from multiple tissues among normal rats (n = 14), leukemic rats treated with ghost (n = 14), or from rats responsive to C6 nanoliposome treatment (n = 5). Note: elimination of leukemic cells after nanoliposomal C6-ceramide therapy in PBMCs, marrow, and lung. Values shown are the mean, with SD in parentheses. ***P < .0005 indicates significance between ghost and C6-ceramide nanoliposome–treated samples (unpaired t test).

Nanoliposomal C6-ceramide liposome treatment induces complete remission in LGL leukemic rats. (A). The Kaplan-Meier survival curves for normal rats (n = 14) or leukemic rats without treatment (n = 14) or with treatment of 40 mg/kg ghost (n = 14) or C6 nanoliposome (n = 14), were plotted. Dashed arrow indicates the start of the treatment. (B) Maintenance of normal white blood counts, hemoglobin values, and platelet counts in responding leukemic rats treated with nanoliposomal C6-ceramide. Blood (200μL) from untreated leukemic rats (n = 14), leukemic rats treated with ghost nanoliposome (n = 14), C6-ceramide nanoliposome (n = 14), and normal rats (n = 14) was collected every week from tail veins of the animals and placed in EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) K2–coated tubes, then complete blood count analysis was performed. Arrow indicates the cessation of the treatment. (C) In vivo therapy with nanoliposomal C6-ceramide leads to resolution of organomegaly in responding LGL leukemic rats. The weight of spleen, liver, and thymus were measured in untreated leukemic rats (n = 14), leukemic rats treated with ghost nanoliposome (n = 14), C6-ceramide nanoliposome-responsive rats (n = 5), and normal rats (n = 14). *P < .05, ***P < .0005 indicates significance between ghost and C6-ceramide nanoliposome–treated samples (unpaired t test). D). Flow cytometry was used to identify rat LGL leukemic cells, which are CD3−CD8a+. Comparison of CD3−CD8a+ NK cells isolated from multiple tissues among normal rats (n = 14), leukemic rats treated with ghost (n = 14), or from rats responsive to C6 nanoliposome treatment (n = 5). Note: elimination of leukemic cells after nanoliposomal C6-ceramide therapy in PBMCs, marrow, and lung. Values shown are the mean, with SD in parentheses. ***P < .0005 indicates significance between ghost and C6-ceramide nanoliposome–treated samples (unpaired t test).

Elimination of leukemic infiltration associated with decreased survivin expression and induction of apoptosis in spleens of leukemic rats responsive to nanoliposomal C6 ceramide. Images were taken from hematoxylin and eosin or immunohistochemically stained 5-μm paraffin sections of rat spleen tissues and analyzed with Olympus 1 × 51 Microscope (Olympus America) attached to Spot Insight Camera (Diagnostic Instruments). The software for imaging and analyses was SPOT Advanced Plus Imaging software. (A) Spleen sections from rats treated with ghost nanoliposome (Ai); with C6 ceramide nanoliposome, responsive (Aii), or nonresponsive (Aiii); and from normal control rat (Aiv) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. (B) Spleen sections from rats treated with ghost nanoliposome (Bi); from C6-ceramide nanoliposome responsive (Bii), or nonresponsive (Biii); and from normal control rat (Biv) were stained with anti-survivin antibody (D-8; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). (C) Spleen sections were stained with an In Situ Cell Death Detection kit to assess the degree of cellular apoptosis via TUNEL-TMR red staining (red); 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole-stained nuclei (blue). Spleen sections from rats responsive to nanoliposomal-C6 (Cii) showed more positive TUNEL staining than sections obtained from rats treated with ghost nanoliposome (Ci), from rats not responding to C6-ceramide nanoliposome (Ciii) and from normal control rat (Civ).

Elimination of leukemic infiltration associated with decreased survivin expression and induction of apoptosis in spleens of leukemic rats responsive to nanoliposomal C6 ceramide. Images were taken from hematoxylin and eosin or immunohistochemically stained 5-μm paraffin sections of rat spleen tissues and analyzed with Olympus 1 × 51 Microscope (Olympus America) attached to Spot Insight Camera (Diagnostic Instruments). The software for imaging and analyses was SPOT Advanced Plus Imaging software. (A) Spleen sections from rats treated with ghost nanoliposome (Ai); with C6 ceramide nanoliposome, responsive (Aii), or nonresponsive (Aiii); and from normal control rat (Aiv) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. (B) Spleen sections from rats treated with ghost nanoliposome (Bi); from C6-ceramide nanoliposome responsive (Bii), or nonresponsive (Biii); and from normal control rat (Biv) were stained with anti-survivin antibody (D-8; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). (C) Spleen sections were stained with an In Situ Cell Death Detection kit to assess the degree of cellular apoptosis via TUNEL-TMR red staining (red); 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole-stained nuclei (blue). Spleen sections from rats responsive to nanoliposomal-C6 (Cii) showed more positive TUNEL staining than sections obtained from rats treated with ghost nanoliposome (Ci), from rats not responding to C6-ceramide nanoliposome (Ciii) and from normal control rat (Civ).

Collectively, these results indicate that bioactive ceramide analogs incorporated into pegylated nanoliposomal vehicles induce complete remission in a rat model of aggressive NK LGL leukemia, possibly via decreased survivin expression or signaling.

Discussion

Here we report for the first time that a C6-ceramide nanoliposomal formulation induced complete remission in a rat model of aggressive LGL leukemia, which is an incurable disease.4 C6-ceramide as short-chain cell-permeable ceramide has been shown to be proapoptotic in many cancer cell types in vitro. However, because of its hydrophobicity, the therapeutic benefit of its bioactivity is limited. We and others have proposed that ceramide can be loaded into nanoliposomal delivery vehicles and used as an anticancer agent for solid tumors such as murine breast cancer and melanomas models in vivo.8,10,38 Our nanoliposomes are formulated at 80 ± 15 nm in size and contain 30 mol% cell-permeable ceramide.8,10 We have previously reported that no lethality was noted at concentrations up to 200 mg/kg (doses 5-fold higher than the present efficacious dose) compared with LD50 values for unencapsulated “free” C6-ceramide of 10 mg/kg.8,10 Furthermore, it appears that in addition to serving as a suitable drug delivery vehicle, our nanoliposomal formulation has the further benefit of delivering ceramide in a much less toxic form. Indeed, we showed that nanoliposomal C6-ceramide formulation had minimal in vitro cytotoxicity for normal donors' PBMCs and was well-tolerated during in vivo treatment of rats with LGL leukemia. Moreover, extensive toxicology studies have shown no biologically significant changes in body weight, organ weight, clinical chemistries, hematology, gross pathology, or histology at the 50-mg/kg dose level in the Sprague-Dawley rat model, supporting a tumor-selective mechanism (detailed information on the toxicology studies of the “Ceramide Liposomes” can be found at http://ncl.cancer.gov/working_technical_reports.asp). The neoplasm-selectivity exhibited by C6-ceramide is probably due to biophysical mechanism by which nanoliposomal C6-ceramide exhibits a bilayer exchange mechanism, which circumvents the lysosomal degradation pathway and allows for immediate distribution of C6-ceramide to well-perfused cancer tissue.39

It is of interest that nanoliposome C6 ceramide had some biologic activity even in animals showing progression of leukemia, as evidenced by decreased white blood cell (blast) counts compared with control animals (Figure 5B). We speculate that variability in leukemia burden at time of initiation of ceramide nanoliposomal therapeutics was a contributing factor to the inability to obtain complete remission in all animals. Neutrophilia is an early sign of leukemia development in this model.35 Indeed, neutrophil counts at day 28 postleukemia cell injection in animals achieving only partial response was 5 times higher than normal levels and 2.5-fold higher than levels seen in animals achieving complete remission (data not shown). Therefore, it is conceivable that animals achieving only a partial response had a higher leukemic burden at initiation of therapy on day 35. Improvement in therapeutic efficacy might be achieved by increasing the dose of the C6 ceramide nanoliposome or by developing next generation C6 ceramide immunonanoliposome targeting CD8 and/or CD56 expressed on leukemic NK cells.

Our results showed accumulation of ceramide in mitochondria of leukemic NK cells. Disruption of the mitochondrial membrane leading to apoptosis induction appears to be the mechanism of ceramide efficacy. As we demonstrated previously, an additional mechanism of ceramide inhibition occurs through decrease in ERK activity via direct blockade of PKC-ϵ and the subsequent incapability to form a signaling complex with Raf-1 and ERK.40 Activation of ERK plays a central role the survival of leukemic NK cells.12 Our data showed that nanoliposomal bioactive C6-ceramide inhibited phosphorylated ERK, reduced survivin expression, and induced caspase-dependent apoptotic cell death in leukemic NK cells in vitro and in vivo. Importantly, we found that inhibition of phosphorylation of ERK via a pharmacologic approach blocked survivin expression in human NKL, a leukemic LGL cell line, and led to apoptosis in leukemic NK cells in patients.12 We next focused our attention on survivin, which belongs to the family of IAPs and functions as an endogenouse inhibitor of caspases,41 the enzymatic effectors of apoptosis.42 Survivin is highly expressed in human cancers, but is barely detectable in most normal adult tissues.43 We found high levels of expression of survivin in leukemic but not normal NK cells. Survivin is functionally involved in both inhibition of apoptosis19,43 and regulation of cell division.44 Specifically, there is a mitochondrial pool of survivin, which is essential for the promotion of tumorigenesis through inhibition of mitochondria-mediated apoptosis by various cell death inducers.19 Interestingly, survivin is not present in mitochondrial fractions of normal tissues. We showed, however, that in leukemic NK cells, survivin was detected in mitochondria (Figure 1C). A previous study has suggested that localization of survivin to mitochondria may be exclusively associated with oncogenic transformation.19 These investigators showed that targeting survivin to mitochondria was sufficient to enhance colony formation in soft agar and accelerate tumor growth in immunodeficient animals. Conversely, forced expression of survivin in cells deficient in transporting survivin to mitochondria resulted in increased apoptosis in vivo.19 Notably, survivin was not localized to the nucleus in the spleen of leukemic rats, further bolstering the notion that survivin functions as an antiapoptotic protein rather than a cell cycle inhibitor in leukemic NK cells (Figure 6B).45

The mechanism underlying antiapoptotic activity by mitochondrial survivin involves binding and sequestration of mitochondrial protein Smac, thus relieving its inhibitory function of caspase suppression.19,46 In addition, mitochondrial survivin binds XIAP, another IAP member, and thereby prevents XIAP from polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation.19 Expression of mitochondrial survivin is sufficient to promote anchorage-independent cell growth, ablate tumor cell apoptosis in vivo, and sustain exponential tumor growth.19 Loss of endogenous mitochondrial survivin correlated with the release of cytochrome c to the cytosol.47 Due to its established direct link to the apoptotic machinery, targeting survivin may achieve a desirable therapeutic window by selectively disabling antiapoptotic phenotypes and/or Fas resistance without affecting the viability of normal tissues, where survivin is largely undetectable.48-50 Indeed, we provide compelling data establishing a novel and unique biochemical mechanism of action for nanoliposomal C6-ceramide in down-regulating expression of survivin. Using C6-ceramide nanoliposomal formulations, we were able to translate these results to the clinical setting by demonstrating complete remission in an animal model of a fatal NK-LGL leukemia.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Della Reynolds at National Cancer Institute for the advice on the culture of RNK-16 cells; Nate Sheaffer and David Stanford of Cell Science/Flow Cytometry Core Facility, Robert Brucklacher of Functional Genomics Core Facility, and Wade Erdis of Microscopy & Histology Core Facility at Penn State Hershey Cancer Institute/Milton S. Hershey Medical Center for their technical assistances; Joseph Hughes for technical support; Jenny Dunkinson for help during the preparation of the manuscript; and Dr Wafik S. El-Deiry for critical reading of the manuscript.

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant nos. CA133525 and CA098472 (to T.P.L.) and Pennsylvania Tobacco Settlement Fund (to M.K.). This project has been also funded in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contracts NO1-CO-12400 and HSN261200800001E (to T.J.S.).

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: X.L., M.K., and T.P.L. designed and organized the experiments; T.J.S. assisted the establishment of Fischer rat NK-LGL leukemia model; X.L., L.R., J.Y., C.A., A.L., R.W., S.T., A.R., and R.Z. performed the animal studies; X.L., L.R., K.B., and R.W. performed real time RT-PCR and Western blot experiments; X.L., L.R., A.L., and R.W. performed the apoptosis assays and MTT studies; X.L. and A.L. performed the confocal experiments; X.L., S.T., A.R., K.L., B.P., J.Y., and F.M. performed the immunohistochemical studies; X.L., L.R., K.T.B., N.J., and K.B. isolated NK cells from normal donors or PBMC from patients; J.K. and S.S. formulated ghost, C6-ceramide nanoliposomes, and cationic nanoliposome for siRNA; J.L. performed the statistic studies; and X.L., M.K., and T.P.L. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.K. Penn State Research Foundation (PSRF), has previously licensed ceramide nanoliposome to Tracon Pharmaceuticals, San Diego, CA. M.K. is Chief Medical Officer of Keystone Nano Inc, State College, PA, which has licensed other nanoscale delivery systems for ceramide from PSRF as well as cationic liposomes for delivery of siRNA. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Xin Liu, Penn State Hershey Cancer Institute, Experimental Therapeutics – CH74, Rm 4401, 500 University Dr, PO Box 850, Hershey, PA 17033-0850; e-mail: Xliu2@hmc.psu.edu.

References

Author notes

X.L., L.R., and J.Y. contributed equally to this work.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal