Abstract

We examined in vivo FLT3 inhibition in acute myeloid leukemia patients treated with chemotherapy followed by the FLT3 inhibitor lestaurtinib, comparing newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia patients with relapsed patients. Because we noted that in vivo FLT3 inhibition by lestaurtinib was less effective in the relapsed patients compared with the newly diagnosed patients, we investigated whether plasma FLT3 ligand (FL) levels could influence the efficacy of FLT3 inhibition in these patients. After intensive chemotherapy, FL levels rose to a mean of 488 pg/mL on day 15 of induction therapy for newly diagnosed patients, whereas they rose to a mean of 1148 pg/mL in the relapsed patients. FL levels rose even higher with successive courses of chemotherapy, to a mean of 3251 pg/mL after the fourth course. In vitro, exogenous FL at concentrations similar to those observed in patients mitigated FLT3 inhibition and cytotoxicity for each of 5 different FLT3 inhibitors (lestaurtinib, midostaurin, sorafenib, KW-2449, and AC220). The dramatic increase in FL level after chemotherapy represents a possible obstacle to inhibiting FLT3 in this clinical setting. These findings could have important implications regarding the design and outcome of trials of FLT3 inhibitors and furthermore suggest a rationale for targeting FL as a therapeutic strategy.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients who harbor the FLT3/ITD mutation have an exceptionally poor prognosis.1,2 During the past decade, efforts have been underway to develop FLT3 inhibitors in the hopes of improving outcomes for these patients.3 Several agents have now been studied as monotherapy for this disease, and the results have been only modestly successful. Although there have been a few remissions reported, the responses are usually limited to clearance of peripheral blasts, with persistence of disease in the marrow. In light of this, attention has turned to incorporating these agents into existing chemotherapy regimens, on the hypothesis that FLT3 inhibition will synergize with chemotherapy in inducing cytotoxicity.4 Alternately, others have postulated that mobilizing the leukemia cells from the marrow might enhance the efficacy of FLT3 inhibition and have therefore tested FLT3 inhibitors in combination with CXCR4 inhibition.5 Several large trials of chemotherapy administered in combination with FLT3 inhibitors are either actively accruing or have recently completed accrual. Because chemotherapy may alter the pharmacokinetics of FLT3 inhibitors and therefore affect target inhibition in vivo, we examined FLT3 inhibition in patients receiving lestaurtinib, an indolocarbazole FLT3 inhibitor, from 2 separate trials in which the agent was combined with chemotherapy. We noted a discrepancy in the degree of FLT3 inhibition, as measured by a plasma inhibitory activity assay, between the 2 groups of patients. We hypothesized that high levels of FLT3 ligand (FL), a cytokine that is known to increase after myelosuppressive therapy, could be interfering with FLT3 inhibition in these trials. We have therefore examined FL levels in response to chemotherapy and FLT3 inhibition, as well as the effect of FL levels on the efficacy of FLT3 inhibitors in vitro and in vivo. Our findings may explain why blasts in the bone marrow are more resistant to FLT3 inhibitors and furthermore have important implications both for FLT3 mutant AML as a disease as well as for efforts to incorporate FLT3 inhibitors into AML therapy.

Methods

Clinical trials

Plasma samples from 4 separate clinical trials of FLT3 inhibitors were used in this study.

The Cephalon 204 trial was a randomized trial of lestaurtinib administered in sequence with chemotherapy for AML patients with FLT3 activating mutations in first relapse.6 Chemotherapy consisted of MEC (mitoxantrone, etoposide, and cytarabine) or high-dose cytarabine. There were 123 total plasma samples from 72 patients on the Cephalon 204 trial available for FLT3 ligand analysis, with corresponding lestaurtinib drug levels on all of them. The MRC AML15 trial was a randomized trial of lestaurtinib administered in sequence with chemotherapy (cytarabine, daunorubicin, and etoposide) for newly diagnosed AML patients with FLT3 activating mutations. Patients on AML15 receive additional cycles of chemotherapy, each followed by lestaurtinib, for a total of 4 courses. The chemotherapy regimens have been previously published.7 A total of 155 plasma samples from 69 patients on the AML15 trial were available for analysis of FL levels (62 from course 1, 43 from course 2, 30 from course 3, and 20 from course 4), but corresponding lestaurtinib drug levels on samples from only 18 of these patients. The CP00001 trial is a phase 1 dose-escalation trial of AC220 in relapsed or refractory AML patients.8 Johns Hopkins Protocol J0509 was an open label dose-escalation study of sorafenib for relapsed or refractory AML patients.9

Patient samples (plasma and blasts)

Leukemia cell specimens, leukemia plasma samples, and normal donor plasma samples were provided by the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins Tumor and Cell Procurement Bank. Collection and shipment of leukemia plasma samples from the MRC AML15 trial were approved by the Wales Multicentre Research Ethics Committee and the Local Research Ethics Committee at each participating institution. All samples used in this study were from patients who gave informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The specimens were obtained by Ficoll-purifying mononuclear cells from the peripheral blood of patients with FLT3/ITD AML. The mononuclear cells were aliquoted and stored frozen in liquid nitrogen in fetal bovine serum with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for repeated use. Before each use, aliquots of these blasts were thawed rapidly into warm culture medium, incubated for 12 hours, and then recentrifuged over Ficoll to eliminate cells dying from the freeze-thaw process. Using this method, we obtained blasts that maintained satisfactory viability (as determined by Trypan blue exclusion) and responsiveness to cytotoxic agents in culture over 72 hours.

Cell culture

All cell lines and primary blast samples were cultured in culture medium, consisting of RPMI/10% fetal bovine serum (Millipore), at 37°C in 5% CO2. Ficoll-Hypaque was obtained from GE Healthcare. Molm-14 cells were obtained from the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen. The TF/ITD cell line was derived by transfecting the GM-CSF–dependent TF-1 cell line with an expression vector containing the FLT3 coding sequence for an ITD mutation from an AML patient, as described.10 The resultant TF/ITD line is growth factor independent and expresses constitutively phosphorylated FLT3.

Cytotoxicity was assessed using a dimethyl-thiazol diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. In selected cases, we also used an annexin-V binding apoptosis assay to confirm that the cytotoxic effect observed (or lack thereof) was associated with an equivalent degree of apoptosis. MTT (Roche Diagnostics) and annexin V (BD Biosciences PharMingen) assays were performed as described previously.11

FLT3 phosphorylation

Leukemia cells were incubated in culture medium or normal donor plasma. Leukemia cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline and then lysed by resuspending them in lysis buffer, made up of 20mM Tris, pH 7.4, 100mM NaCl, 1% Igepal (Sigma-Aldrich), 1mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 2mM NaVO4, plus Complete protease inhibitor (Roche Diagnostics). After rocking for 30 minutes in lysis buffer, the extracts were clarified by centrifugation at 16 000g and the supernatants were assayed for protein (Bio-Rad). A 50-μg aliquot was removed as whole-cell lysate for analysis of STAT5, and the remainder was used for immunoprecipitation with anti-FLT3. Anti-FLT3 antibody (S18; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was added to the extract for overnight incubation, and then protein A-Sepharose (Upstate Biotechnology) was added for 2 additional hours. Separate sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels for whole-cell lysate and immunoprecipates were run in parallel. After transfer to Immobilon membranes (Millipore), immunoblotting was performed with antiphosphotyrosine antibody (4G10; Upstate Biotechnology) to detect phosphorylated FLT3, and then stripped and reprobed with anti-FLT3 antibody to measure total FLT3. Proteins were visualized using chemiluminescence (ECL; GE Healthcare), exposed on Kodak BioMax XAR Film, developed, and scanned using a Bio-Rad GS800 densitometer. The concentration of drug for which the phosphorylation of FLT3 was inhibited to 50% or 80% of its baseline (IC50 or IC80), or for cytotoxicity, was determined using linear regression analysis of the dose-response curves after linear transformation using an exponential model (CalcuSyn software Version 2.1; Biosoft).

Inhibitors

Five FLT3 inhibitors were used in this study: lestaurtinib (CEP-701), midostaurin (PKC412), AC220, sorafenib (BAY43-9006), and KW-2449.11-15 FLT3 inhibitors were obtained as powder and dissolved in DMSO at stock concentrations of 10mM. Stocks were aliquoted into 10-μL volumes and stored at −80°C and thawed immediately before use. Lestaurtinib was supplied by Cephalon. AC220 was supplied by Ambit Biosciences. KW-2449 was supplied by Kyowa Kirin. Sorafenib and midostaurin were obtained from LC Laboratories. All samples in any given experiment contained identical concentrations of DMSO, which were always < 0.01%.

Plasma inhibitory activity assay

For the plasma inhibitory activity (PIA), assay was performed as described.16 Briefly, frozen plasma samples were thawed and clarified by centrifugation at 16 000g for 2 minutes. For each time point, 2 × 106 TF/ITD were incubated with 1 mL plasma at 37°C for 1 hour. The cells were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and then lysed. After immunoblotting for phosphorylated FLT3 as described in “FLT3 phosphorylation,” densitometric analysis was performed on the bands, and the PIA for each plasma sample was calculated by expressing the density of its corresponding band as a percentage of the density of the baseline band (which was arbitrarily set at 100%).

FL ELISA

FL concentrations in plasma samples were determined using an ELISA kit obtained from R&D Systems.

Pharmacokinetics

Plasma samples from studies 204 and AML15 were analyzed for concentrations of lestaurtinib by the Department of Drug Safety and Disposition of Cephalon, using a validated high-performance liquid chromatography method. The method used liquid-liquid extraction of lestaurtinib and an internal standard (KT-252a) from 0.1 mL of human plasma into a mixture of ethyl acetate/methylene chloride 4:1 (volume/volume) followed by reversed-phase chromatography on a Hypersil BDS phenyl column (2.1 × 150 mm; 5-μm particle size; Thermo Fisher Scientific) maintained at 35°C. Chromatography was isocratic, with a mobile phase consisting of a 70:30 (volume/volume) mixture of water/acetonitrile. The eluate was monitored by fluorescence detection with an excitation wavelength of 303 nm and an emission wavelength of 403 nm. Quantification was based on a 1/χ2-weighted linear regression analysis of the peak height ratios of lestaurtinib to the internal standard versus nominal concentration, from extracted human plasma calibration standards. The quantifiable range of the assay was from 5.00 to 1000 ng/mL of human plasma. Within-run and between-run coefficients of variation over the assay range during method validation were less than or equal to 6.5% and less than or equal to 9.9%, respectively. Within-run accuracy and between-run accuracy were 94.9% to 113% and 101% to 104%, respectively.

α1-acid glycoprotein

α1-acid glycoprotein was assayed using an immunodiffusion assay kit obtained from Kent Laboratories.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using a Student 2-tailed t test.

Results

More effective FLT3 inhibition seen in newly diagnosed versus relapsed patients

Using a PIA assay for FLT3,16 we examined in vivo FLT3 inhibition in AML patients treated with chemotherapy followed by lestaurtinib, comparing newly diagnosed AML patients (enrolled on the MRC AML15 trial) with relapsed patients enrolled on the Cephalon 204 trial. Both groups of patients had been treated with a 3-drug regimen followed by lestaurtinib dosed twice daily. The dose of lestaurtinib in the AML15 trial ranged from 40 mg to 80 mg twice daily. Using plasma samples collected at or near trough time points on day 15 from the beginning of chemotherapy, for which we had both PIA data and lestaurtinib drug levels measured (72 from the 204 trial and 18 from the AML15 trial), in patients taking 80 mg twice daily of lestaurtinib, we were interested to note that in vivo FLT3 inhibition by lestaurtinib appeared to be distinctly less effective in the relapsed patients (204 trial) compared with the newly diagnosed patients (AML15 trial). Preliminary data from both trials indicate that FLT3 inhibition to less than 15% of baseline at this time point is strongly correlated with remission in both groups of patients.6,17 As summarized in Table 1, the mean level of FLT3 activity, as determined from the PIA assay, on day 15 for patients in the AML15 trial is significantly (P = .0004) less than for those in the 204 trial. Both groups of patients were receiving the same dose of lestaurtinib, and samples were collected on or around day 15. In vitro and early phase clinical studies of lestaurtinib and other FLT3 inhibitors indicated that FLT3 autophosphorylation needed to be suppressed to less than 15% of baseline to induce a cytotoxic effect in AML cells.10,11,15,16 Of 78 samples available for this analysis from the 204 trial, only 46 (59%) achieved this target level of inhibition, whereas all 18 AML15 samples analyzed were less than 15% of baseline FLT3 activity. Based on results from the monotherapy trials of lestaurtinib,10,18 we had predicted that trough levels of 5μM in vivo would be sufficient to induce FLT3 inhibition to this degree. However, despite a mean plasma level of 12.3μM (Table 1), inhibition in the 204 trial patients was significantly less effective than for those in AML15. This could in part be explained by the fact that plasma levels of lestaurtinib were modestly higher for the AML15 patients (16.4μM vs 12.3μM, P = .102; Table 1), but the failure to achieve a more consistent level of FLT3 inhibition in the relapse patients was still unexpected, given the trough plasma concentrations observed. Lestaurtinib is highly protein bound, particularly to α1-acid glycoprotein, such that higher plasma levels of this acute phase reactant could potentially limit free drug levels in the 204 trial patients. However, α1-acid glycoprotein levels were actually modestly higher in the AML15 trial patients (Table 1); hence, this would not explain the difference in inhibitory activity.

Lestaurtinib trough plasma levels and FLT3 inhibitory activity from day 15 samples of AML15 versus Cephalon 204 trial patients

| . | Cephalon 204 trial . | AML15 trial . |

|---|---|---|

| No. of samples | 78 | 18 |

| Lestaurtinib, μM (mean) | 12.3 | 16.4* |

| Mean FLT3 activity, % baseline, all patients (range) | 17.9 (0.8-76.9) | 3.0† (0-74.6) |

| % FLT3 inhibited (n/N) | 59 (46/78) | 100‡ (18/18) |

| α1-acid glycoprotein, mg/dL (range) | 181 (92-287) | 224§ (90-450) |

| . | Cephalon 204 trial . | AML15 trial . |

|---|---|---|

| No. of samples | 78 | 18 |

| Lestaurtinib, μM (mean) | 12.3 | 16.4* |

| Mean FLT3 activity, % baseline, all patients (range) | 17.9 (0.8-76.9) | 3.0† (0-74.6) |

| % FLT3 inhibited (n/N) | 59 (46/78) | 100‡ (18/18) |

| α1-acid glycoprotein, mg/dL (range) | 181 (92-287) | 224§ (90-450) |

All patients received 80 mg twice-daily lestaurtinib, started after completion of chemotherapy (which began on day 1). Mean FLT3 activity represents the mean of values obtained from the PIA assay for these time points for all 78 samples. Percentage FLT3 inhibited refers to the percentage of patients for whom FLT3 was inhibited to less than the target of ≤ 15% of baseline.

P = .102.

P = .0004.

P < .0001.

P < .0001.

Plasma FLT3 ligand levels are elevated after chemotherapy

FL has been previously shown to influence the in vitro effects of lestaurtinib.19,20 Furthermore, it has previously been shown that plasma FL levels rise during periods of bone marrow aplasia induced by chemotherapy or radiation.21-27 Given that in both of these trials lestaurtinib was administered after intensive chemotherapy, we decided to examine FL levels in the plasma samples available to us. To derive an estimate of FL levels in newly diagnosed AML patients, we tested plasma from 7 consecutive AML patients presenting to our institution at diagnosis. The FL levels for these 7 patients ranged from 2 to 6 pg/mL, with a mean of 3 pg/mL and an SD of 2 pg/mL. For AML patients at first relapse, we tested 72 baseline plasma samples from the Cephalon 204 trial. In these patients, there was considerably more variation in FL levels, ranging from 2 pg/mL to as high as 2953 pg/mL (mean ± SD, 57 ± 348 pg/mL). Shown in Figure 1A are the individual and mean FL levels for day 15 of course 1 of induction therapy for the newly diagnosed AML15 patients compared with day 15 of salvage chemotherapy for the relapsed Cephalon 204 trial patients. Although there is wide individual variation in FL levels in both trials, as a group the relapsed patients have significantly higher levels. We also had plasma samples available from subsequent courses of chemotherapy from the AML15 trial (all on day 15 of each course), and mean FL levels rise higher with each subsequent course (Figure 1B). The FL level on day 15 of the second course of chemotherapy for the AML15 patients was comparable in magnitude with that seen in the relapse patients on day 15 of their salvage therapy. Previous studies have shown that FL levels rise and then fall after aplasia-inducing therapy.25,26 From the Cephalon 204 trial, we also had plasma samples collected on or around day 42 with which we were able to examine FL levels in individual patients during recovery from a single course of chemotherapy. Results from these samples (Figure 1C) indicate that in many cases FL levels remain elevated for weeks after initiation of therapy.

Plasma FL levels from clinical trial patients. (A) Plasma samples obtained on day 15 of induction therapy for newly diagnosed (left) versus relapsed (right) FLT3 mutant AML patients were assayed for FL by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. (B) FL levels from plasma samples obtained from newly diagnosed FLT3 mutant AML patients. Course 1 was induction; and courses 2-4 were consolidation. The course 1 samples correspond to the samples on the left in panel A. For course 1, the mean FL concentration was 488 pg/mL (range, 3-4099 pg/mL); for course 2, the mean was 1196 pg/mL (range, 34-8889 pg/mL); for course 3, the mean was 2298 pg/mL (range, 30-5451 pg/mL); for course 4, the mean was 2145 pg/mL (range, 76-7108 pg/mL). (C) FL plasma levels from individual patients on the Cephalon 204 trial at 3 different time points during therapy. For the baseline samples, there was a single sample measuring 2953 pg/mL. Twenty-two baseline samples had FL levels below the limit of detection for the assay (eg, < 2 pg/mL). These samples were listed as having 2 pg/mL. For the baseline samples, the median was 5 pg/mL, the mean was 57 pg/mL, and the range was from undetectable to 2298 pg/mL. For the day 15 samples, the mean was 1173 pg/mL, the median was 721 pg/mL, and the range was 19 to 3818 pg/mL. For the day 42 samples, the median was 187 pg/mL, the mean was 642 pg/mL, and the range was 4 to 5767 pg/mL.

Plasma FL levels from clinical trial patients. (A) Plasma samples obtained on day 15 of induction therapy for newly diagnosed (left) versus relapsed (right) FLT3 mutant AML patients were assayed for FL by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. (B) FL levels from plasma samples obtained from newly diagnosed FLT3 mutant AML patients. Course 1 was induction; and courses 2-4 were consolidation. The course 1 samples correspond to the samples on the left in panel A. For course 1, the mean FL concentration was 488 pg/mL (range, 3-4099 pg/mL); for course 2, the mean was 1196 pg/mL (range, 34-8889 pg/mL); for course 3, the mean was 2298 pg/mL (range, 30-5451 pg/mL); for course 4, the mean was 2145 pg/mL (range, 76-7108 pg/mL). (C) FL plasma levels from individual patients on the Cephalon 204 trial at 3 different time points during therapy. For the baseline samples, there was a single sample measuring 2953 pg/mL. Twenty-two baseline samples had FL levels below the limit of detection for the assay (eg, < 2 pg/mL). These samples were listed as having 2 pg/mL. For the baseline samples, the median was 5 pg/mL, the mean was 57 pg/mL, and the range was from undetectable to 2298 pg/mL. For the day 15 samples, the mean was 1173 pg/mL, the median was 721 pg/mL, and the range was 19 to 3818 pg/mL. For the day 42 samples, the median was 187 pg/mL, the mean was 642 pg/mL, and the range was 4 to 5767 pg/mL.

Others have reported that FLT3 inhibition can result in up-regulation of FL expression.28 Because all patients in our study were treated with lestaurtinib, it was possible that FLT3 inhibition was augmenting the chemotherapy-induced increase in FL levels. To determine the effect of FLT3 inhibition in vivo on FL plasma levels (alone, in the absence of chemotherapy), we tested plasma samples from patients treated with 2 other FLT3 inhibitors, sorafenib or AC220, on clinical trials. We tested 16 samples, all of which were obtained from patients with in vivo FLT3 inhibition to less than 15% of baseline for at least 2 continuous weeks (by PIA assay; results not shown). The levels of FL in these patients during FLT3 inhibitor therapy ranged from 4 to155 pg/mL (mean, 32 pg/mL), essentially the same as those seen in untreated patients, and approximately 2 orders of magnitude less than the levels seen in patients after chemotherapy.

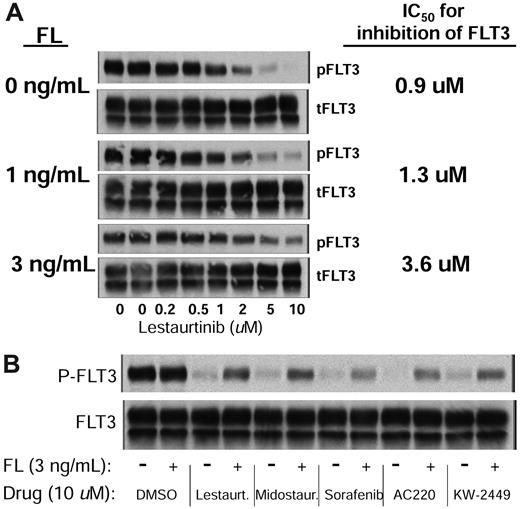

We next wished to characterize the effects of FL on the efficacy of FLT3 inhibitors in vitro. Molm14 cells, which harbor a FLT3/ITD mutation,29 were incubated in increasing concentrations of lestaurtinib in the presence of 0, 1, or 3 ng/mL of exogenous FL. These FL concentrations were chosen because they were similar to those measured on day 15 in the Cephalon 204 trial patients. As shown in Figure 2A, FL induces an upward shift in the dose-response curve for inhibition of FLT3 autophosphorylation by lestaurtinib in plasma. There is a down-regulation of phosphorylated and total FLT3 in response to the addition of FL (presumably because of receptor internalization); but strikingly, at higher concentrations of lestaurtinib, FLT3 autophosphorylation is still very much evident compared with the same experiment performed in the absence of FL. At concentrations of 10μM in plasma, which is a level frequently observed in the trial patients, 3 ng/mL FL results in significant residual FLT3 autophosphorylation compared with that seen in the absence of FL (Figure 2A). The addition of FL resulted in the down-regulation of total and phosphorylated FLT3, which has been described in the literature and can be seen in Figure 2A.30 Because of this receptor down-regulation, the kinetics of FLT3 inhibition are not first order; therefore, IC50 calculations after linear transformation may not be accurate estimates of the true effect, but we have nonetheless included them in this analysis. We performed parallel experiments using culture medium rather than plasma and observed a similar degree of shift in the dose-response curves (data not shown).

FL impairs inhibition of FLT3 autophosphorylation in vitro. (A) Molm14 cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of lestaurtinib in the presence of 0, 1, and 3 ng/mL of FL in plasma for 2 hours. FLT3 autophosphorylation was then evaluated by immunoblotting (gels, left) by immunoprecipitating FLT3, and then, after electrophoresis and transfer to membrane, probing with antiphosphotyrosine. The bands were analyzed by densitometry and plotted (graph, right). (B) Molm14 cells were incubated in plasma with 10μM of the indicated drug and 0 ng/mL (−) or 3 ng/mL (+) of FL for 2 hours. FLT3 autophosphorylation was then evaluated by immunoblotting.

FL impairs inhibition of FLT3 autophosphorylation in vitro. (A) Molm14 cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of lestaurtinib in the presence of 0, 1, and 3 ng/mL of FL in plasma for 2 hours. FLT3 autophosphorylation was then evaluated by immunoblotting (gels, left) by immunoprecipitating FLT3, and then, after electrophoresis and transfer to membrane, probing with antiphosphotyrosine. The bands were analyzed by densitometry and plotted (graph, right). (B) Molm14 cells were incubated in plasma with 10μM of the indicated drug and 0 ng/mL (−) or 3 ng/mL (+) of FL for 2 hours. FLT3 autophosphorylation was then evaluated by immunoblotting.

We performed similar dose-response experiments (data not shown), in medium and plasma, for other FLT3 inhibitors (sorafenib, AC220, PKC412, and KW-2449). In all cases, the addition of FL resulted in loss of complete inhibition by these agents at the highest doses used and an upward shift in the dose-response curves. Figure 2B illustrates the effects that the addition of 3 ng/mL FL has on the inhibitory efficacy of all of these drugs in plasma.

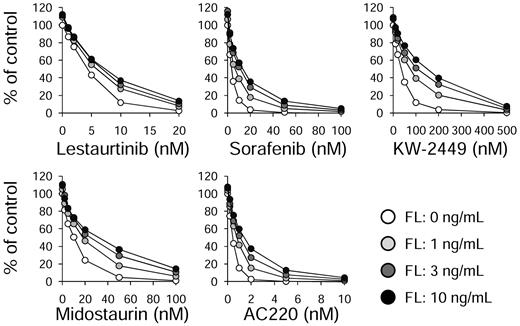

Because the intent of inhibiting FLT3 autophosphorylation in AML is to induce a cytotoxic response, we wished to determine whether the cytotoxic effects of these FLT3 inhibitors were also mitigated by the addition of FL. Molm14 cells were incubated for 48 hours with increasing concentrations of both FLT3 inhibitors and FL, and then assayed for cytotoxic effect (Figure 3). For all drugs analyzed, FL increased the IC50 and IC80 values for cytotoxicity. The results are summarized in Table 2.

FL impairs the cytotoxic effects of FLT3 inhibitors. Molm14 cells were incubated in cell culture medium (RPMI with 10% fetal bovine serum) with increasing concentrations of the indicated drugs for 48 hours in the presence of 0, 1, 3, and 10 ng/mL of FL. Cell viability was then determined using the MTT assay. Results are plotted as percentage DMSO control.

FL impairs the cytotoxic effects of FLT3 inhibitors. Molm14 cells were incubated in cell culture medium (RPMI with 10% fetal bovine serum) with increasing concentrations of the indicated drugs for 48 hours in the presence of 0, 1, 3, and 10 ng/mL of FL. Cell viability was then determined using the MTT assay. Results are plotted as percentage DMSO control.

Cytotoxicity assay results for FLT3 inhibitors in the presence or absence of FL

| Inhibitor/values, nM . | Exogenous FL, ng/mL . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 . | 1 . | 3 . | 10 . | |

| Lestaurtinib | ||||

| IC50 | 3.3 | 5.3 | 6.3 | 6.8 |

| IC80 | 7.1 | 11 | 13 | 15 |

| Midostaurin | ||||

| IC50 | 7.2 | 14 | 23 | 25 |

| IC80 | 17 | 43 | 59 | 86 |

| Sorafenib | ||||

| IC50 | 3.3 | 5.9 | 10 | 12 |

| IC80 | 7.1 | 16 | 26 | 34 |

| AC220 | ||||

| IC50 | 0.38 | 0.69 | 0.92 | 1.3 |

| IC80 | 0.75 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 3.3 |

| KW-2449 | ||||

| IC50 | 28 | 62 | 85 | 114 |

| IC80 | 58 | 166 | 231 | 296 |

| Inhibitor/values, nM . | Exogenous FL, ng/mL . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 . | 1 . | 3 . | 10 . | |

| Lestaurtinib | ||||

| IC50 | 3.3 | 5.3 | 6.3 | 6.8 |

| IC80 | 7.1 | 11 | 13 | 15 |

| Midostaurin | ||||

| IC50 | 7.2 | 14 | 23 | 25 |

| IC80 | 17 | 43 | 59 | 86 |

| Sorafenib | ||||

| IC50 | 3.3 | 5.9 | 10 | 12 |

| IC80 | 7.1 | 16 | 26 | 34 |

| AC220 | ||||

| IC50 | 0.38 | 0.69 | 0.92 | 1.3 |

| IC80 | 0.75 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 3.3 |

| KW-2449 | ||||

| IC50 | 28 | 62 | 85 | 114 |

| IC80 | 58 | 166 | 231 | 296 |

Molm14 cells were incubated for 48 hours with increasing concentrations of FLT3 inhibitors in the presence of increasing concentrations of FL and then assayed for cytotoxic effect using an MTT assay. The concentration of drug for which the optical density was reduced to 50% or 80% of its baseline was determined using linear regression analysis of the dose-response curves after linear transformation using an exponential model. All r values in these experiments were ≥ 0.99.

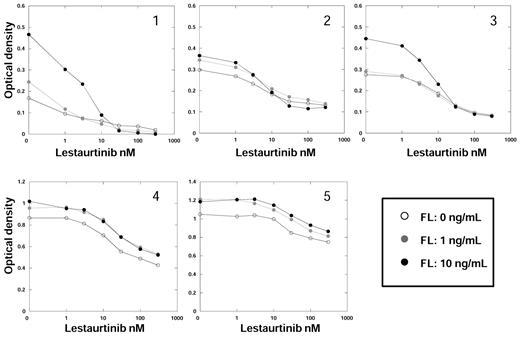

In 5 primary samples from AML patients with FLT3/ITD mutations (Figure 4), we observed a similar pattern of response to FL and FLT3 inhibition. For all 5 samples, the addition of exogenous FL increased the metabolic activity of the sample in culture medium and resulted in a relative upward shift in the cytotoxicity dose-response curve. However, the degree of shift in the dose-response curves was more variable than what we observed in the cell lines. IC50 values were not calculated for these experiments because of the lack of first-order kinetics and because in some cases a reduction of metabolic activity to less than 50% of baseline did not occur over the drug concentrations used.

FL impairs the cytotoxic effects of FLT3 inhibitors in primary AML samples. Five different primary AML blast samples, each harboring a FLT3/ITD mutation, were incubated in culture medium with increasing concentrations of the indicated drugs for 48 hours in the presence of FL, as in Figure 3. Cell viability was then determined using the MTT assay. Results are plotted as percentage DMSO control. Each point represents the average of quadruplicate optical density measurements. The error bars were omitted for figure clarity but, for each point, amounted to < 5% of the optical density value.

FL impairs the cytotoxic effects of FLT3 inhibitors in primary AML samples. Five different primary AML blast samples, each harboring a FLT3/ITD mutation, were incubated in culture medium with increasing concentrations of the indicated drugs for 48 hours in the presence of FL, as in Figure 3. Cell viability was then determined using the MTT assay. Results are plotted as percentage DMSO control. Each point represents the average of quadruplicate optical density measurements. The error bars were omitted for figure clarity but, for each point, amounted to < 5% of the optical density value.

Increased FL levels are associated with decreased FLT3 inhibition in vivo

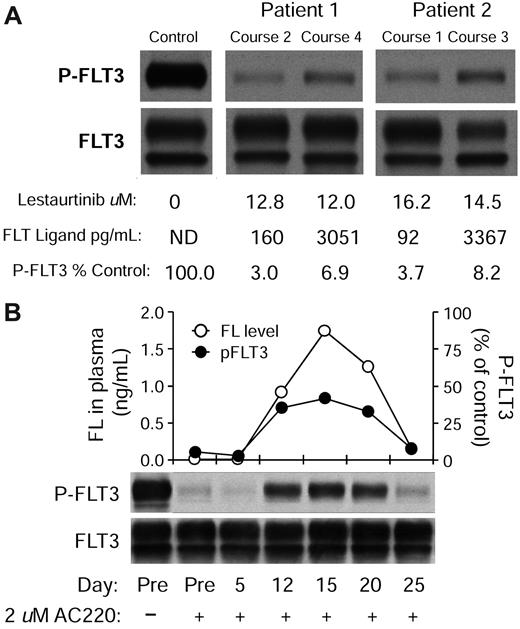

The continuous rise of FL levels with successive courses of chemotherapy leads to the prediction that in vivo FLT3 inhibition by lestaurtinib would be less effective after the first induction course. In confirmation of this, the mean PIA value from course 1 of the AML15 trial (18 samples total analyzed) was 3% of baseline, whereas in courses 2 through 4 (18 samples total) the value was 6.8% (P = .04). To better establish an association between elevated FL levels and impairment of FLT3 inhibition, we examined the dataset for cases in which individual patients had similar plasma concentrations of lestaurtinib at 2 different time points during treatment but different levels of FL. Shown in Figure 5A are 2 such cases. In both cases, the FL concentration rose from a low level to more than 3 ng/mL, and in both cases the intensity of FLT3 autophosphorylation is more than 2-fold higher in the samples with the elevated FL. FLT3 activity is still sufficiently reduced from baseline such that a cytotoxic effect would be predicted, indicating that high drug levels can overcome the mitigating effects of high plasma FL levels, at least in these cases.

FL impairs inhibition of FLT3 autophosphorylation in vivo. (A) Plasma samples from 2 individual patients treated on the MRC AML15 trial were collected at different time points and then assessed for FLT3 inhibitory activity (PIA assay). Cells were exposed to the plasma for 3 hours and then lysed. FLT3 was immunoprecipitated, subjected to electrophoresis, and transferred to a membrane. The blot was probed with antiphosphotyrosine (top row), then stripped and reprobed with anti-FLT3 (bottom row). FL and lestaurtinib levels were determined from the same plasma samples as described in “FL ELISA” and “Pharmacokinetics.” (B) Plasma was collected from a single newly diagnosed AML patient at different time points after diagnosis and treatment with induction chemotherapy (cytarabine, daunorubicin, and etoposide). The plasma was assayed for FL levels by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and plotted (○). In parallel, AC220 was added to a concentration of 2μM for each time point and used to incubate Molm14 cells for 2 hours. Each sample was then assayed for FLT3 inhibitory activity as in panel A. The densitometric analysis of the phospho-FLT3 blot (top blot; ●).

FL impairs inhibition of FLT3 autophosphorylation in vivo. (A) Plasma samples from 2 individual patients treated on the MRC AML15 trial were collected at different time points and then assessed for FLT3 inhibitory activity (PIA assay). Cells were exposed to the plasma for 3 hours and then lysed. FLT3 was immunoprecipitated, subjected to electrophoresis, and transferred to a membrane. The blot was probed with antiphosphotyrosine (top row), then stripped and reprobed with anti-FLT3 (bottom row). FL and lestaurtinib levels were determined from the same plasma samples as described in “FL ELISA” and “Pharmacokinetics.” (B) Plasma was collected from a single newly diagnosed AML patient at different time points after diagnosis and treatment with induction chemotherapy (cytarabine, daunorubicin, and etoposide). The plasma was assayed for FL levels by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and plotted (○). In parallel, AC220 was added to a concentration of 2μM for each time point and used to incubate Molm14 cells for 2 hours. Each sample was then assayed for FLT3 inhibitory activity as in panel A. The densitometric analysis of the phospho-FLT3 blot (top blot; ●).

To better characterize the effects of chemotherapy-induced FL increases on FLT3 inhibition within a single patient, we collected plasma from a newly diagnosed AML patient (without a FLT3 mutation) at diagnosis and then every 5 days after induction chemotherapy. The chemotherapy regimen consisted of cytarabine 667 mg/m2 per day by continuous infusion on days 1 to 3, daunorubicin 45 mg/m2 per day on days 1 to 3, and etoposide 400 mg/m2 per day on days 8 to 10. This was a more dose-intense regimen than either of the ones used in the lestaurtinib trials. We measured FL levels in the plasma from these time points (Figure 5B), and then, in a parallel experiment, we added our most potent FLT3 inhibitor, AC220,13,31 to a concentration of 2μM to each plasma time point sample. The AC220-containing plasma was then used to incubate Molm14 cells, and phosphorylated FLT3 was then evaluated by immunoblot. As shown in Figure 5B, FL levels rise after chemotherapy, reach a peak on day 15, and then fall back near baseline by day 25. In parallel with the FL curve, the inhibitory activity of AC220 is significantly blunted between days 12 and 20, to the point at which FLT3 autophosphorylation is nearly 50% of baseline. This degree of FLT3 inhibition would correlate with significant loss of cytotoxic activity, extrapolating from preclinical in vitro studies with this agent.13

Discussion

The concept of inhibiting FLT3 as a potential targeted therapy for FLT3-mutated AML is based on extensive preclinical studies.11,29,32 These studies demonstrated that the degree of cytotoxic effect induced by FLT3 inhibitors was dependent on the degree of FLT3 inhibition achieved. Subsequent clinical studies indicate that the degree of clinical response to these agents is likewise tightly correlated with the degree of FLT3 inhibition achieved.10,15 A primary problem with FLT3 inhibitors thus far has been a general lack of potency: a significant fraction of patients treated with FLT3 inhibitors, such as lestaurtinib, midostaurin, and KW-2449, have had only partial FLT3 inhibition in vivo.10,15,33 Although combining a targeted therapy with conventional chemotherapy has become a common strategy, in the case of targeting FLT3 in AML, we have identified a unique obstacle to this approach. As previously reported by others, and confirmed with our data, FL levels can rise to the nanogram per milliliter range after chemotherapy, and successive courses of chemotherapy lead to even greater increases. Because AML therapy is predicated on the administration of recurrent courses of chemotherapy, FL levels are probably elevated through most of induction and consolidation. In relapse patients, the rise in FL levels appears to be even more rapid. These concentrations of FL clearly impair the efficacy of FLT3 inhibitors in vitro, and our data suggest that the impairment could conceivably be occurring in vivo as well. The relapsed patients as a group had higher FL levels and less effective FLT3 inhibition compared with the newly diagnosed patients receiving their first induction; moreover, we were able to identify a limited number of individual patient cases to corroborate this. These conclusions, of course, are based on a relatively small sample set and will need to be validated using larger sample sets from future clinical trials. Because the degree of FLT3 inhibition is so closely correlated to the degree of cytotoxicity induced, even a modest degree of impairment of inhibition probably influences the success of this therapy. Consistent with this is the finding of Zhou et al that resistance to the FLT3 inhibitor ABT-869 was associated with a modest increase in autocrine FL expression by leukemia cells.28

The degree to which FL impairs the ability of a drug like lestaurtinib to inhibit FLT3 appears to be modest, but highly reproducible. In data that have been presented in abstract form, and currently being submitted for publication, PIA results from the Cephalon 204 trial show only slight variation when performed on the same patient sample 3 separate times. We have noted previously that relatively small changes in the PIA assay predict clinical responses.10 The assay therefore appears quite robust, as least as far as lestaurtinib is concerned.

Although the mechanism by which FL impairs the activity of FLT3 inhibitors is not clear, the phenomenon of a ligand influencing the activity of kinase inhibitors has been observed with the endothelial growth factor receptor.34 Lapatinib has significantly reduced affinity for the ligand-activated endothelial growth factor receptor, analogous to what we have observed for FLT3 inhibitors in this study. Interestingly, erlotinib, another EGFR inhibitor, actually has a higher affinity for the activated/ligand-bound receptor compared with the inactive form. FLT3 inhibitors, it may be surmised, uniformly bind the inactive receptor with the highest affinity. Indeed, many kinase inhibitors are thought to bind to the inactive conformation of the kinase.35 Based on the concentrations of ligand and inhibitor, the active or inactive conformation is favored at equilibrium. This would imply that the effects of FL could be overcome with sufficient inhibitor or with a more potent inhibitor.

In the case of lestaurtinib, elevated FL levels are almost certainly not the only reason for inadequate FLT3 inhibition in vivo. The drug has very complex pharmacokinetics, wide variations in plasma levels, and is highly protein bound to an acute phase reactant (α1-acid glycoprotein). Furthermore, it seems very possible that other cytokines may have been influencing the activity of FLT3 in these patients. However, our in vitro findings strongly suggest that all FLT3 inhibitors will be subject to the effects of FL in patients.

The MRC AML15 trial is continuing to accrue patients (now in the context of the AML17 trial). In preliminary data, a high complete remission rate has been reported, which would be consistent with the high level of FLT3 inhibition evident in the course 1 samples shown here.17 It remains to be seen whether or not there will be a long-term benefit to continued treatment with lestaurtinib.

In addition to the Cephalon 204 and MRC AML15/17 trials, there are 2 additional trials examining the potential clinical benefit of combining FLT3 inhibition with chemotherapy. Ravandi et al reported on the feasibility of administering sorafenib with induction chemotherapy for newly diagnosed AML patients, including both FLT3-mutated and FLT3 wild-type cases.36 Twelve of 13 (92%) FLT3 mutant patients achieved a remission. In vivo FLT3 inhibition was assayed using the PIA assay, but only on day 7 of induction. Although FLT3 was fully inhibited in all patients assayed, the day 7 time point would have been well before any rise in FL levels. In this trial, sorafenib was administered only during the first 7 days of induction, but for 28-day cycles during consolidation chemotherapy. Our data would predict that FL levels might well impair sorafenib's ability to inhibit FLT3 during these consolidation courses.

The RATIFY trial is a randomized phase 3 trial testing the potential clinical benefit of the addition of PKC412 to induction chemotherapy for newly diagnosed FLT3 mutant AML patients.37 Although PKC412 has been shown to effectively inhibit FLT3 in vivo when administered as a single agent,33 it is not clear whether it will have the necessary potency to inhibit the target in the context of the high FL levels we predict will occur with successive doses of chemotherapy. Because PKC412 is administered during induction, it may have its greatest efficacy early on, before FL levels rise. In preliminary data, the investigators reported a high complete remission rate, again consistent with what was seen in the AML15 and sorafenib trials.37

In general, our data suggest that an ideal FLT3 inhibitor would be one that can achieve plasma levels well in excess of what is required to fully inhibit FLT3 in the context of a monotherapy trial. In addition, these findings may shed light on the difficulty in achieving a marrow response with FLT3 inhibitors. Bone marrow stroma and T lymphocytes are thought to be the principal sources of circulating FL induced during aplasia.26 Cell surface expression of FL by bone marrow stroma and by the high density of AML cells within the marrow would seem to have significant potential to interfere with FLT3 inhibitors. One novel approach to this problem would be to mobilize the leukemia cells away from the stroma (and from each other) using something other than chemotherapy, and then use a FLT3 inhibitor. Zeng et al have reported just such an approach using a CXCR4 inhibitor, with success in an animal model.5 In future trials combining FLT3 inhibitors with chemotherapy, one viable strategy may be to use the inhibitor only during the first week of induction chemotherapy, and once remission is achieved (and FL levels have returned to near baseline), reintroduce the inhibitor as maintenance therapy.

In conclusion, it may be hypothesized that FL is an important driver in FLT3 mutant AML and may have a strong influence on prognosis. AML patients with FLT3 mutations can routinely be put into remission with induction chemotherapy but have a high relapse rate. Despite the presence of an activating mutation, FLT3 mutant AML cells remain highly responsive to stimulation by FL.38 One could speculate that the high level of FL that would be predicted to be present in patients during consolidation therapy may actually be protective, or even stimulatory, to residual FLT3 mutant stem cells. This hypothesis could be tested prospectively by correlating FL levels with relapse rates in clinical trials in which FLT3 mutant AML patients are enrolled. Extending this concept yet further, a monoclonal antibody targeting FL, administered in the context of chemotherapy or concomitantly with FLT3 inhibitors, could have significant therapeutic benefit for AML patients.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

Edward Hellriegel, Sharon Song, and Elsie Grau (Cephalon Inc, Frazer, PA) conducted the analysis of plasma samples for lestaurtinib concentrations. The study sponsors for both the CP00001 trial (Ambit Biosciences Inc, La Jolla, CA) and for the Cephalon 204 trial (Cephalon Inc) were aware of and approved this study.

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (Leukemia SPORE P50 CA100632-06, R01 CA128864) and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (M.L.). M.L. is a Clinical Scholar of the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. The Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins Tumor and Cell Procurement Bank is supported by the Regional Oncology Research Center (grant 2 P30 CA 006973-44).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: T.S. conducted experiments, helped design the study, and helped edit the manuscript; X. Y. conducted experiments; S.K., P.W., and A.B. (the principal investigator for the MRC AML15 trial) coordinated the collection and shipment of plasma samples from the AML15 trial, provided the pharmacokinetic data, and helped edit the manuscript; B.D.S. and S.G. coordinated the collection of plasma samples from all other patients; B.D.S. was the principal investigator for the J0509 trial of sorafenib; D.S. helped design the study and edited the manuscript; and M.L. (the principal investigator for the Cephalon 204 trial) designed the study, conducted experiments, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.L. and S.K. have served as consultants to Cephalon Inc. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mark Levis, Kimmel Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, 1650 Orleans St, Rm 243, Baltimore, MD 21231; e-mail: levisma@jhmi.edu.