Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cells are generated in the bone marrow (BM) from lymphoid progenitors. Although several different maturation states of committed NK cells have been described, the initial stages of NK-cell differentiation from the common lymphoid progenitor are not well understood. Here we describe the identification of the earliest committed NK-cell precursors in the BM. These precursors, termed pre-pro NK cells, lack the expression of most canonical NK cell–specific surface markers but express the transcription factor inhibitor of DNA binding 2 and high levels of the IL-7 receptor. In vitro differentiation studies demonstrate that pre-pro NK cells are committed to NK-cell lineage and appear to be upstream of the previously identified NK-cell progenitor population.

Introduction

Although the developmental stages leading to committed B and T cells have been dissected in great detail,1 the developmental intermediates downstream of the common lymphoid progenitor (CLP) leading to a committed natural killer (NK)–cell precursor remain poorly defined. The earliest committed NK-cell progenitor (NKP) identified to date is characterized through the expression of the IL-2 receptor β chain (CD122) and the lack of pan-NK–cell surface markers (NK1.1 and CD49b), but this population is likely to be heterogeneous because only a minority of cells give rise to NK cells in in vitro assays.2,3

The transcription factor inhibitor of DNA binding 2 (ID2) is essential for NK-cell development. In its absence, fetal and adult NK-cell development is blocked at an early stage.4-7 Id2 inhibits E proteins in NK cells and is itself regulated by E4BP4, which is also required for the differentiation of NKPs to immature NK cells.8,9 Using a reporter line in which the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene has been introduced into the Id2 locus, we report the identification of the earliest committed NK-cell precursor in adult BM. By analogy to B-cell development, we termed these pre-pro NK cells, and they express high levels of ID2, IL-7Rα (CD127), and lack expression of most, but not all, NK-cell markers. Furthermore, we demonstrate that ID2gfp expression can be used to isolate the committed NK-cell progenitors within the heterogeneous NKP population.

Methods

Mice

We generated ID2gfp reporter mice by inserting an internal ribosome entry site-GFP cassette into the 3′ untranslated region of the Id2 locus (G.T.B., S.C., and S.L.N. manuscript submitted April 2011). PU.1gfp and Rag1gfp mice have been described previously.10,11 All mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute according to institute guidelines.

Antibodies, cell analysis, and sorting

Lineage (lin) marker–positive BM cells were depleted and analyzed by flow cytometry as described in supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Cell culture

To determine precursor frequencies, sorted progenitors cells were seeded in limiting dilution on OP9 or OP9-DL1 cells in the presence of 2% IL-7 supernatant and 5 ng/mL FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (Flt3) ligand for B- and T-cell development, respectively, and on OP9 cells plus 0.5% IL-7 supernatant and 50 ng/mL human IL-15 (R&D Systems) for NK-cell differentiation as described.12 After 7-10 days, wells were scored for the presence of colonies. Colonies were harvested for flow cytometric analysis, and precursor frequency was calculated according to Poisson statistics with the use of ELDA (extreme limiting dilution analysis) software Version 1.0 (http://bioinf.wehi.edu.au/software/elda/).13

Results and discussion

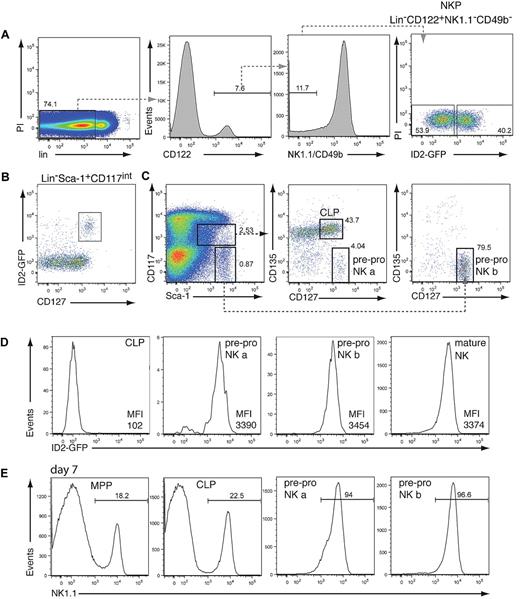

The earliest committed NKP identified to date expresses CD122 but not the pan-NK cell–specific markers NK1.1 and CD49b.2 This population is likely to be heterogeneous because only 8%-40% of NKPs are reported to have unilineage NK-cell potential.2,3,14 To test whether ID2 expression can be used to identify committed NK-cell progenitors, we analyzed the NKP population by using mice that have GFP introduced into the Id2 locus (ID2gfp). Flow cytometric analysis showed that lin−CD122+NK1.1−CD49b− NKPs could be subdivided into low and high ID2-expressing cells (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 1A). To examine if ID2gfp expression marks, the NK cell–committed NKPs, ID2gfp-high, and ID2gfp-low NKP cells were sorted and cultivated on OP9 stromal cells in the presence of IL-15, conditions that induce NK-cell development. Strikingly, only ID2gfp-high NKPs efficiently generated NK1.1+CD49b+ NK cells (Table 1).13 The authors of a recent report14 showed that the NKP population consists of NK cell–restricted and NK/T bipotent precursor cells. Although we obtained similar results with unfractionated NKPs, we found that only NK-cell potential was enriched in ID2gfp-high cells (data not shown). Thus, the NK-cell lineage–committed fraction of the NKP can be readily identified by the use of ID2gfp-high expression.

Lineage potential of hematopoietic precursor cells

| Precursor cell . | Frequency of mature lineage colonies . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| NK . | B . | T . | |

| NKP ID2-GFPhigh | 1:2.4 | 1:4681 | 1:7884 |

| 1:4.4 | 1:9462 | 1:7884 | |

| 1:2.4 | NC | NC | |

| 1:2.5 | ND | NC | |

| Mean NKP ID2-GFPhigh (95% CI) | 1:3.0 (2.6-3.6) | 1:6540 (2116-20 213) | 1:9448 (2494-39 673) |

| NKP ID2-GFPlow | 1:75 | 1:361 | 1:67 |

| 1:965 | 1:1821 | 1:172 | |

| 1:146.9 | 1:298 | 1:52.8 | |

| 1:129.7 | ND | 1:31.7 | |

| Mean NKP ID2-GFPlow (95% CI) | 1:337 (267-426) | 1:574 (409-805) | 1:138 (115-166) |

| CLP | 1:2.0 | 1:1.8 | 1:2.6 |

| 1:2.7 | 1:2.8 | ND | |

| 1:1.9 | ND | 1:1.8 | |

| 1:2.1 | 1:2.4 | ND | |

| 1:5.8 | 1:2.3 | ND | |

| 1:8.8 | 1:6.9 | ND | |

| Mean CLP (95% CI) | 1:2.4 (2.01-2.92) | 1:2.4 (1.91-2.97) | 1:2.1 (1.58-2.72) |

| pre-pro NK a | 1:1.6 | 1:239 | 1:113 |

| 1:3.4 | 1:159 | ND | |

| 1:1.4 | ND | 1:2046 | |

| 1:1.8 | 1:684 | ND | |

| 1:5.5 | 1:287 | ND | |

| pre-pro NK b | 1:1.8 | ND | 1:379 |

| 1:6.9 | 1:479 | ND | |

| Mean pre-pro NK (95% CI) | 1:2.4 (1.98-2.89) | 1:242 (150-392) | 1:416 (269-644) |

| Precursor cell . | Frequency of mature lineage colonies . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| NK . | B . | T . | |

| NKP ID2-GFPhigh | 1:2.4 | 1:4681 | 1:7884 |

| 1:4.4 | 1:9462 | 1:7884 | |

| 1:2.4 | NC | NC | |

| 1:2.5 | ND | NC | |

| Mean NKP ID2-GFPhigh (95% CI) | 1:3.0 (2.6-3.6) | 1:6540 (2116-20 213) | 1:9448 (2494-39 673) |

| NKP ID2-GFPlow | 1:75 | 1:361 | 1:67 |

| 1:965 | 1:1821 | 1:172 | |

| 1:146.9 | 1:298 | 1:52.8 | |

| 1:129.7 | ND | 1:31.7 | |

| Mean NKP ID2-GFPlow (95% CI) | 1:337 (267-426) | 1:574 (409-805) | 1:138 (115-166) |

| CLP | 1:2.0 | 1:1.8 | 1:2.6 |

| 1:2.7 | 1:2.8 | ND | |

| 1:1.9 | ND | 1:1.8 | |

| 1:2.1 | 1:2.4 | ND | |

| 1:5.8 | 1:2.3 | ND | |

| 1:8.8 | 1:6.9 | ND | |

| Mean CLP (95% CI) | 1:2.4 (2.01-2.92) | 1:2.4 (1.91-2.97) | 1:2.1 (1.58-2.72) |

| pre-pro NK a | 1:1.6 | 1:239 | 1:113 |

| 1:3.4 | 1:159 | ND | |

| 1:1.4 | ND | 1:2046 | |

| 1:1.8 | 1:684 | ND | |

| 1:5.5 | 1:287 | ND | |

| pre-pro NK b | 1:1.8 | ND | 1:379 |

| 1:6.9 | 1:479 | ND | |

| Mean pre-pro NK (95% CI) | 1:2.4 (1.98-2.89) | 1:242 (150-392) | 1:416 (269-644) |

T-, B-, and NK-lineage potential within the NKP population and pre-pro NK-cell populations is shown. Limiting dilution analysis of NKPs (sorted as described in Figure 1 into ID2gfp-high and ID2gfp-low cells), CLPs, and pre-pro NK-cell subsets a and b (as described in Figure 1C) from Id2gfp/gfp BM. Sorted populations were cultured in either NK-, B-, or T-cell permissive conditions as described in “Methods.” Precursor frequency and 95% CIs were determined by the software application ELDA (ie, extreme limiting dilution analysis).13 Note the data from the pre-pro NK a and b populations has been combined for this analysis.

CI indicates confidence interval; CLP, common lymphoid progenitor; GFP, green fluorescent protein; ID2, inhibitor of DNA binding 2; NC, no colonies present; ND, not determined; NK, natural killer; and NKP, natural killer–cell progenitor.

To determine the earliest expression of ID2gfp within the NK-cell lineage, and thus potentially the earliest committed BM-derived NK-cell precursor, hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell populations were analyzed for ID2gfp expression by flow cytometry. Although very low ID2gfp expression was observed in the hematopoietic stem cell–enriched lin−Sca-1+CD117+ population (supplemental Figure 1A), pronounced ID2gfp fluorescence was found within the gate containing the lymphoid-restricted CLP population, defined as lin−Sca-1+CD117intCD127+ (Figure 1B). ID2gfp+ cells, however, differed from the CLP15 in that they expressed very high levels of CD127 and lacked expression of CD135 (Flt3; Figure 1C-D). Most ID2gfp+ cells were found outside of the CLP gate in the lin−Sca-1highCD117− fraction, which also expressed high levels of CD127 and lacked CD135 (Figure 1C-D). This population has been observed previously by other groups. Although they found B and T lineage potential in the CD135+ fraction, the lineage potential of CD135−CD127high cells has remained elusive.16-18 When cultured on OP9 cells plus IL-7 and IL-15, both ID2gfp-expressing populations efficiently generated NK1.1+ NK cells within 1 week of cultivation, whereas sorted multipotent progenitors and CLP were delayed in their capacity to differentiate into NK1.1+ cells (Figure 1E). Given their immature surface marker phenotype and NK-cell potential, we termed these cells pre-pro NK a and pre-pro NK b cells by analogy to the hierarchical B-cell developmental system.

Analysis of ID2gfp expression in NK cell progenitors. (A) BM-derived NKP cells from Id2gfp/gfp mice, identified by their expression of CD122 and lack of NK1.1, DX5, and the lineage (lin) markers CD3, CD8, CD11b, CD19, Gr-1, and Ter119, were analyzed for ID2gfp expression (n = 3). (B) ID2gfp expression in lin−Sca-1+CD117intermediate (int) BM cells derived from Id2gfp/gfp mice (n > 5). (C-D) Expression of Sca-1, CD117, CD127, CD135, and ID2gfp within the lin− BM cells of Id2gfp/gfp mice. Progenitor populations were electronically gated as indicated (n > 5). For panels A and C, numbers in the plots indicate the percentage of cells within the boxed region. Pre-pro NK a cells represented 0.056% ± 0.017% of lin− BM cells (1893 ± 585 cells/2 femurs, n = 4) and pre-pro NK b cells represented 0.283% ± 0.115% of lin− BM cells (9614 ± 3920 cells/2 femurs, n = 4). (D) CLP (lin−Sca-1+CD117intCD127+CD135+), pre-pro NK a (lin−Sca-1+CD117intCD127+CD135−), and pre-pro NK b (lin−Sca-1+CD117−CD127+CD135−) cells (gated as in panel C) and mature NK cells (NK1.1+CD49b+) were analyzed for ID2gfp expression (n > 5). Mean fluorescence index of GFP of the indicated populations is shown. (E) Multipotent progenitors (MPP, lin−Sca1+CD117+CD135+CD127−), CLP, pre-pro NK a, and pre-pro NK b progenitor cells were sorted from Id2gfp/gfp bone marrow by flow cytometry and cultured for 7 days in IL-7 and IL-15 on OP9 stromal cells (n = 2). Numbers indicate the percentage of NK1.1+ NK cells in the cultures.

Analysis of ID2gfp expression in NK cell progenitors. (A) BM-derived NKP cells from Id2gfp/gfp mice, identified by their expression of CD122 and lack of NK1.1, DX5, and the lineage (lin) markers CD3, CD8, CD11b, CD19, Gr-1, and Ter119, were analyzed for ID2gfp expression (n = 3). (B) ID2gfp expression in lin−Sca-1+CD117intermediate (int) BM cells derived from Id2gfp/gfp mice (n > 5). (C-D) Expression of Sca-1, CD117, CD127, CD135, and ID2gfp within the lin− BM cells of Id2gfp/gfp mice. Progenitor populations were electronically gated as indicated (n > 5). For panels A and C, numbers in the plots indicate the percentage of cells within the boxed region. Pre-pro NK a cells represented 0.056% ± 0.017% of lin− BM cells (1893 ± 585 cells/2 femurs, n = 4) and pre-pro NK b cells represented 0.283% ± 0.115% of lin− BM cells (9614 ± 3920 cells/2 femurs, n = 4). (D) CLP (lin−Sca-1+CD117intCD127+CD135+), pre-pro NK a (lin−Sca-1+CD117intCD127+CD135−), and pre-pro NK b (lin−Sca-1+CD117−CD127+CD135−) cells (gated as in panel C) and mature NK cells (NK1.1+CD49b+) were analyzed for ID2gfp expression (n > 5). Mean fluorescence index of GFP of the indicated populations is shown. (E) Multipotent progenitors (MPP, lin−Sca1+CD117+CD135+CD127−), CLP, pre-pro NK a, and pre-pro NK b progenitor cells were sorted from Id2gfp/gfp bone marrow by flow cytometry and cultured for 7 days in IL-7 and IL-15 on OP9 stromal cells (n = 2). Numbers indicate the percentage of NK1.1+ NK cells in the cultures.

We further characterized the 2 pre-pro NK-cell populations by analyzing the expression of surface makers characteristically expressed on maturing NK cells (for a summary of surface markers, see Huntingon et al1 and Boos et al19 ). Pre-pro NK cells did not express NK-cell markers such as CD122, NK1.1, CD49b, or NKp46, but they did express the NK receptors CD244 (2B4) and NKG2D (supplemental Figure 1B). On cultivation under NK cell–specific conditions, pre-pro NK-cell subsets sequentially up-regulated CD122 and NK1.1 expression (supplemental Figure 1C). These data indicate that pre-pro NK cells represent more immature precursors than the NKPs, given their lack of CD122 expression and may represent the direct precursor of the NKP population.

To characterize pre-pro NK cells in an ID2gfp-independent manner, a gating strategy was established that took advantage of the uniquely high expression of CD127 and absence of CD135 in these populations (as described in Figure 1C). By using this strategy, we found that PU.1 and Rag1, 2 factors that are expressed in CLPs and developing B and T cells,10,20-22 were already silenced in pre-pro NK cells (supplemental Figure 2). These data show that pre-pro NK cells have established a unique gene expression signature within the lymphoid lineages and argue against a role of either protein in the NK-cell lineage.

To determine the lineage potential and purity of the identified pre-pro NK-cell populations, limiting dilution experiments under B cell–, T cell–, and NK cell–specific conditions were performed. Sorted CLP and pre-pro NK a and b cells were cultivated either on OP9 stroma plus specific cytokines for B- and NK-cell development or OP9-DL1 stromal cells plus IL-7 and Flt3L for T-cell development.12 As expected, CLP efficiently differentiated into all 3 lymphoid lineages. In contrast both pre-pro NK-cell populations gave rise to only NK-cell colonies at a high frequency (Table 1). These data suggest that despite the differences in CD117 expression the 2 pre-pro NK-cell subsets a and b are phenotypically and functionally similar, and we propose to summarize these 2 fractions into one pre-pro NK-cell precursor population.

In conclusion, by initially using the ID2gfp reporter mouse model and later high levels of CD127, we have prospectively identified and characterized the pre-pro NK cells that likely represents the direct precursor of the earlier described NKP, whose purity can also be greatly enhanced by use of the ID2gfp reporter. Identification of the earliest steps in NK-cell formation will now enable a detailed molecular characterization of the lineage commitment process in NK cells.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the facilities of our institute, particularly those responsible for animal husbandry and flow cytometry.

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia. G.T.B. is supported by fellowships from the Sylvia and Charles Viertel Charitable Foundation and Howard Hughes Medical Institute; S.L.N. is supported by a Pfizer Senior Research Fellowship (Australia); S.H.M.P. is supported by a Leukemia Foundation of Australia Scholarship; and S.C. is supported by an NHMRC fellowship.

Howard Hughes Funding

Authorship

Contribution: S.C., S.H.M.P., S.L.N., and G.T.B. designed research, performed research, prepared an initial draft based on a systematic review of published literature, and discussed the draft.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Sebastian Carotta or Gabrielle Belz, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, 1G Royal Parade, Melbourne, Victoria 3052, Australia; e-mail: carotta@wehi.edu.au or belz@wehi.edu.au.

References

Author notes

S.L.N and G.T.B contributed equally to this work.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal