Abstract

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly destructive toward cellular macromolecules. However, moderate levels of ROS can contribute to normal cellular processes including signaling. Herein we evaluate the consequence of a pro-oxidant environment on hematopoietic homeostasis. The NF-E2 related factor 2 (Nrf2) transcription factor regulates genes related to ROS scavenging and detoxification. Nrf2 responds to altered cellular redox status, such as occurs with loss of antioxidant selenoproteins after deletion of the selenocysteine-tRNA gene (Trsp). Conditional knockout of the Trsp gene using Mx1-inducible Cre-recombinase leads to selenoprotein deficiency and anemia on a wild-type background, whereas Trsp:Nrf2 double deficiency dramatically exacerbates the anemia and increases intracellular hydrogen peroxide levels in erythroblasts. Results indicate that Nrf2 compensates for defective ROS scavenging when selenoproteins are lost from erythroid cells. We also observed thymus atrophy in single Trsp-conditional knockout mice, suggesting a requirement for selenoprotein function in T-cell differentiation within the thymus. Surprisingly, no changes were observed in the myelomonocytic or megakaryocytic populations. Therefore, our results show that selenoprotein activity and the Nrf2 gene battery are particularly important for oxidative homeostasis in erythrocytes and for the prevention of hemolytic anemia.

Introduction

Antioxidant enzyme activity helps define the parameters of the cellular redox environment. Excessive amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) can lead to aging, senescence and disease pathogenesis, such as occurs in arteriosclerosis, diabetes, and cancer.1-3 Conversely, moderate levels of oxidative stress can be beneficial, being exploited in cellular signaling pathways,4 the release of hematopoietic stem cells from the bone marrow niche,5 for the clearance of infection by the immune system,6 and the recruitment of leukocytes to wounded tissue.7

An essential group of antioxidant enzymes are the selenoproteins, which contain selenium in the form of selenocysteine, an amino acid incorporated during protein translation by a specific transfer RNA molecule, tRNASec.8 Selenoproteins number 25 in humans and antioxidant members comprise (1) the glutathione peroxidase (GPx) enzymes that reduce hydrogen- and lipid-peroxides, (2) thioredoxin reductase (TR) that has an essential role in maintaining thioredoxin in a reduced and active state, (3) methionine sulphoxide reductase that repairs oxidative modification of methionine residues, and (4) selenoprotein P, which acts both as a selenium carrier molecule and as a phospholipid hydroperoxidase.9,10

Previously, we demonstrated that loss of selenoproteins in liver and macrophage, by deletion of the tRNAsec gene (Trsp), leads to the activation of a basic leucine zipper transcription factor NF-E2 related factor 2 (Nrf2). The transcription of a large number of antioxidant and detoxification enzymes are under the regulation of Nrf2 due to the presence of an antioxidant response element within their gene regulatory regions.11,12 Identified target genes of Nrf2 include heme-oxygenase 1 (HO-1), glutathione S-transferase family members, the glutathione biosynthetic enzyme γ-glutamyl-cysteine synthetase,13 and NAD(P)H (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate-oxidase) quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1).14

Selenium/selenoprotein deficiency has previously been shown to compromise the function of various immune cell types,15-17 and low serum selenium has been suggested to contribute to anemia in humans.18-20 Therefore, we were interested in evaluating the relative importance of selenoprotein activity for the homeostasis of hematopoietic lineages. In addition, our previous results showing overlapping but nonredundant function of selenoproteins and Nrf2 in cellular redox maintenance prompted us to consider the interaction of these 2 antioxidant systems. Our results show that selenoproteins and Nrf2 play a co-operative and critical role in regulating the intracellular ROS levels and survival of red blood cells (RBCs) whereas loss of selenoprotein activity alone leads to a decrease in lymphoid cells and thymic involution, with characteristics of premature aging.

Methods

Generation and genotyping of Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre mice

Experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Experiment Committee of Tohoku University, and experiments were carried out in accordance with the Regulation for Animal Experiments of Tohoku University. Trspfl/del, Mx1-Cre and Nrf2–/– mice were produced and characterized as described previously.11,21,22 The fl and del stand for floxed and deleted alleles of Trsp, respectively. Compound mutant (Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre and Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del::Mx1-Cre) animals were generated on a mixed 129/Sv and C57BL/6 background. Cre expression and subsequent Trsp excision was induced by intraperitoneal injection of polyinosine-polycyticylic acid (pI-pC, either from Sigma-Aldrich or GE Healthcare) every other day. In the case of pI-pC sourced from Sigma-Aldrich, 250 μL of pI-pC solution (2 mg/mL in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) was injected 14 times, whereas for pI-pC from GE Healthcare, a 250 μL solution (1 mg/mL in PBS) was injected 10 times. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) genotyping of Trsp allele in bone marrow, spleen, and liver were carried out as described previously.21

Immunoblot analysis

Cell lysate from bone marrow, spleen, and liver were prepared using sample buffer (50mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 10% glycerol, 2mM EDTA [ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid], 1mM PMSF [phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride], 0.15mM β-mercaptoethanol). These proteins were resolved by 15% SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. GPx1 protein was detected using a 1:2000 dilution of the rabbit GPx1 antiserum prepared previously.23

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from whole bone marrow cells using the ISOGEN method (Nippon Gene Co Ltd.). cDNAs were synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using Superscript II (Life Technologies). The RNA transcripts for NQO1, glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit (GCLC), HO-1, and thioredoxin reductase 1 (TXNRD1) were quantified by real-time reverse-transcription (RT)–PCR. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using an Applied Biosystems 7300 sequence detector. The primer sequences used are shown in a previous report.24

Hematological analysis

For analysis of complete blood counts, peripheral blood from the retro-orbital vein was analyzed by a hemocytometer (Nihon Kohden Co.). For the sequential examination of hematocrit (Hct) values, blood collected from the tail vein was analyzed by centrifugation in microhematocrit tubes. Peripheral blood smears were stained with Wright-Giemsa. Reticulocyte counts were examined manually using blood smears stained with new methylene blue.

Measurement of serum immunoglobulin levels and serum erythropoietin concentrations

Immunoglobulin concentrations were determined as described previously.25 Serum erythropoietin concentrations were measured using a photometric enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay (Epo ELISA kit; Roche).

Clinical biochemistry

Serum samples were collected, and total and direct bilirubin levels were determined by an automated biochemical analyzer DRI-CHEM 7000V (Fuji Film).

Histopathological analyses

For hematoxylin and eosin staining, the spleen and thymus were fixed in 3.7% formalin and embedded in paraffin. To visualize thymic lipid content, thymus was fixed in 3.7% formalin and embedded in Optimal Cutting Temperature compound (Tissue-Tek). Frozen sections were stained with Oil Red O (Muto Pure Chemicals).

Flow cytometric analysis and reactive oxygen measurement

Mononucleated cell suspensions from the bone marrow, spleen, and thymus were prepared and resuspended in PBS supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum. The following were purchased from BD Pharmingen: fluorescein phycoerythrin-conjugated antibodies against CD71, CD19, and CD8; allophycocyanin-conjugated anti–c-Kit, Ter119, B220, and CD4 antibodies. Intracellular ROS were measured using the membrane-permeable fluorescent dye 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA; Molecular Probes). Cells were incubated with H2DCFDA at a final concentration of 5mM for 30 minutes at 37°C. Cells were washed and resuspended in PBS with 2% fetal bovine serum for flow cytometric analysis using FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences). Dead cells were excluded by propidium iodide staining. For each analysis, 10 000 events were recorded.

Microscopy

Microscopic images were taken using a LEICA DM RBE microscope (40× and 20× objectives) equipped with an Olympus DP71 microscope digital camera. Image acquisition was performed using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe).

Statistical analysis

The Student t test was used to calculate statistical significance (P). Results in which P was < .05 were considered statistically significant for all tests. All error bars represent ± SEM.

Results

Induced deletion of Trsp inhibits selenoprotein synthesis in hematopoietic tissues

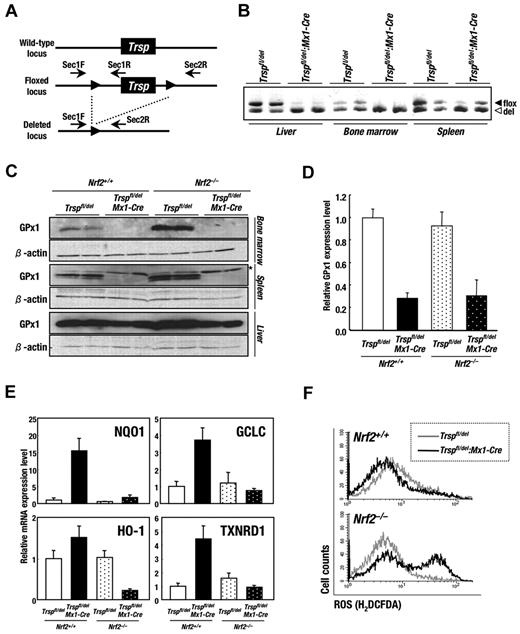

To clarify the role of selenoproteins in the homeostasis of hematopoietic cells, we generated an inducible knockout mouse for the Trsp gene using the Cre-loxP system. An Mx1-Cre transgenic mouse strain22 was used to induce the deletion of the Trsp gene in vivo (Figure 1A). Transcription of the Mx1-Cre transgene is responsive to interferon, which is rapidly produced by multiple tissues after injection of the double-stranded RNA analog pI-pC. Trspfl/del and Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre animals were subjected to pI-pC treatment as described in “Generation and genotyping of Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre mice” and euthanized after a period of 4 weeks. PCR analysis was used to examine the recombination status of the Trsp locus in tissues from Trspfl/del and Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre mice. As shown Figure 1B, the efficiency of deletion was highest in liver and bone marrow (almost 100%), with significant recombination also being observed in spleen (approximately 80%).

Deletion of Trsp gene leads to increased oxidative stress and induction of Nrf2-target genes in hematopoietic tissues. (A) The targeting strategy for Trsp gene by the Cre-loxP recombination system. Trsp gene is flanked with 2 loxP sequences, designated by closed arrowheads. Arrows indicate the position of primers used for PCR analysis in B. (B) PCR analysis of Trspfl/del and Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre mice after the pI-pC treatment. Fragments derived from floxed allele (494 bp; filled triangles) and recombined allele (465 bp; open triangles) were amplified by SeC1F and SeC1R primer pair and SeC1F and SeC2R primer pair, respectively. (C) Expressions of GPx1 protein in Trspfl/del and Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre mice on an Nrf2+/+ or Nrf2–/– background were examined by immunobloting. Note that the levels of GPx1 protein were significantly decreased in hematopoietic organs of Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre mice, although those in livers were preserved. Nonspecific bands are indicated by asterisk. (D-E) Expressions of GPx1 (D), NQO1, GCLC, HO-1, and TXNRD1 (E) mRNA in whole bone marrow cells from mice of each genotype were examined by real-time RT-PCR. Ribosomal 18S subunit was used as an internal control. (F) ROS levels in whole bone marrow cells of Trspfl/del and Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre mice on an Nrf2+/+ (top panel) or Nrf2–/– background (bottom panel) were evaluated by flow cytometry using the redox-sensitive dye H2DCFDA.

Deletion of Trsp gene leads to increased oxidative stress and induction of Nrf2-target genes in hematopoietic tissues. (A) The targeting strategy for Trsp gene by the Cre-loxP recombination system. Trsp gene is flanked with 2 loxP sequences, designated by closed arrowheads. Arrows indicate the position of primers used for PCR analysis in B. (B) PCR analysis of Trspfl/del and Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre mice after the pI-pC treatment. Fragments derived from floxed allele (494 bp; filled triangles) and recombined allele (465 bp; open triangles) were amplified by SeC1F and SeC1R primer pair and SeC1F and SeC2R primer pair, respectively. (C) Expressions of GPx1 protein in Trspfl/del and Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre mice on an Nrf2+/+ or Nrf2–/– background were examined by immunobloting. Note that the levels of GPx1 protein were significantly decreased in hematopoietic organs of Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre mice, although those in livers were preserved. Nonspecific bands are indicated by asterisk. (D-E) Expressions of GPx1 (D), NQO1, GCLC, HO-1, and TXNRD1 (E) mRNA in whole bone marrow cells from mice of each genotype were examined by real-time RT-PCR. Ribosomal 18S subunit was used as an internal control. (F) ROS levels in whole bone marrow cells of Trspfl/del and Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre mice on an Nrf2+/+ (top panel) or Nrf2–/– background (bottom panel) were evaluated by flow cytometry using the redox-sensitive dye H2DCFDA.

We carried out immunoblot analysis of whole cell extract from bone marrow, spleen, and liver for the intracellular selenoprotein GPx1. The production of GPx1 protein was significantly decreased in the bone marrow and spleen of Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre mice (Figure 1C). In contrast, although the Trsp gene was almost completely deleted in liver (Figure 1B), no significant decrease of GPx1 protein was observed for unknown reasons (Figure 1C). The GPx1 mRNA levels in the bone marrow of Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre mice were found to be 30% that of Trspfl/del mice (Figure 1D). Similar results were obtained from the analysis of GPx1 mRNA on an Nrf2 knockout background (Figure 1D). These observations are consistent with previous reports showing that failure to supply adequate tRNASec compromises the decoding capacity of the selenocysteine UGA codon and increases the susceptibility of selenoprotein transcripts to degradation by nonsense-mediated decay (NMD).8

We also noticed that the GPx1 protein levels in the bone marrow of Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del mice were higher than that of Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del animals (Figure 1C). It was not expected that selenoprotein synthesis would be enhanced by Nrf2 deficiency. Because no significant change in the GPx1 mRNA level was observed between Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del and Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del mice (Figure 1D), we surmise that Nrf2 deficiency might enhance the translation efficiency of selenoproteins or perhaps stabilize the proteins from degradation.

Deletion of Trsp in hematopoietic tissues leads to increased oxidative stress and induction of Nrf2-target genes

We previously reported that the transcription of Nrf2 target genes is induced in selenoprotein-deficient macrophage and liver.21 Therefore, we examined the expression of Nrf2 target genes in whole bone marrow cells of selenoprotein- and/or Nrf2-deficient mice (Figure 1E). NQO1, GCLC, HO-1, and TXNRD1 mRNA levels were greatly increased in Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice. On the contrary, the deletion of Nrf2 genes from bone marrow cells of Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice substantially impaired the induction of NQO1, GCLC, HO-1, and TXNRD1, verifying the role that this transcription factor has in responding to the loss of selenoproteins.

The induction of Nrf2-regulated cytoprotective enzymes is presumably a cellular response to compensate for an absence of important selenoprotein activities, in particular the antioxidant function that this group of enzymes performs. This possibility was explored by comparing ROS levels in whole bone marrow cells isolated from control mice relative to cells from a single and double-knockout background using the redox-sensitive dye H2DCFDA. In the presence of Nrf2, no difference in intracellular ROS levels were observed between Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) and control (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del) mice (Figure 1F top panel). However, a significant increase in ROS levels occurred in a population of Trsp-null cells, relative to control cells, in the absence of Nrf2 (Figure 1F bottom panel). Note that there is an unaffected population of Trsp-Nrf2 double-knockout cells in the bone marrow, suggesting variability in the susceptibility of certain cell populations to ROS production. To verify the importance of Nrf2 to ROS scavenging, we examined the production of ROS by bone marrow cells that were treated with hydrogen peroxide (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). It was found that hydrogen peroxide promoted a significant increase in ROS levels in Nrf2-null cells relative to that of controls. These results demonstrate that Nrf2 functionally responds to the deficiency of selenoproteins in bone marrow by the elimination of ROS.

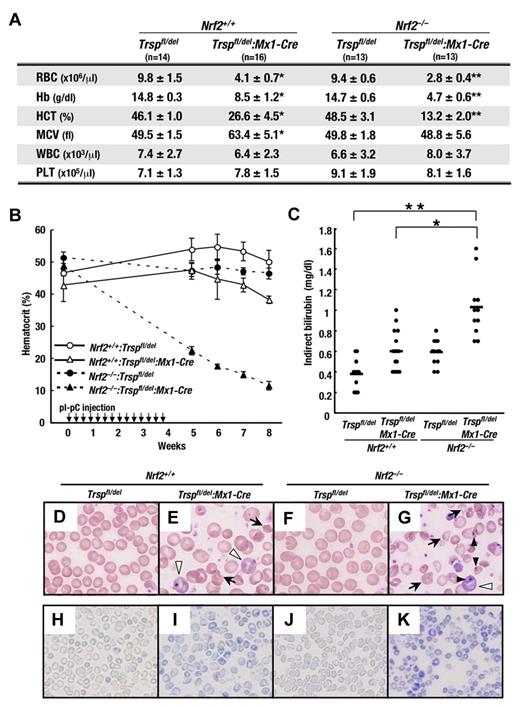

Nrf2 protects against hemolytic anemia induced by the loss of Trsp

To evaluate the effects of selenoprotein and Nrf2 deficiency on hematopoiesis in animals, we examined the peripheral blood status of Trsp-deficient (Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice in the presence or absence of Nrf2. Blood was collected from the retro-orbital venous plexus 8 weeks after the first pI-pC injection (or 4 weeks after the final pI-pC injection; Figure 2A). The number of RBCs, hemoglobin concentration, and Hct in Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice was decreased to approximately 60% that of control (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del) mice. Importantly, an even greater decrease of these hematopoietic indices to approximately 30% of control values was observed in Nrf2:Trsp double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice, whereas Nrf2-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del) mice failed to develop anemia. Interestingly, the white blood cell counts and platelet levels remained largely unchanged in all genotypes.

Hemolytic anemia caused by loss of Trsp gene is partially compensated by Nrf2. (A) Peripheral blood counts of mice at 4 weeks after the final pI-pC injection. RBC, red blood cell; Hb, hemoglobin; HCT, hematocrit; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; WBC, white blood cell; PLT, platelet. *P < .01 and **P < .001 compared with values obtained from Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del mice. (B) Hct kinetics of mice treated with pI-pC. The day of the first pI-pC injection is depicted as 0. (C) Plasma indirect bilirubin levels were determined at 4 weeks after final pI-pC injection. Horizontal lines represent average values in each genotype (*P < .05; **P < .01). (D-K) Peripheral blood smears of mice at 4 weeks after the final pI-pC injection were stained with Wright-Giemsa (D-G) or new methylene blue (H-K). Arrows, white arrowheads, and black arrowheads indicate the poikilocytes, immature erythrocytes with basophilic cytoplasm, and erythrocytes with Howell-Jolly body, respectively.

Hemolytic anemia caused by loss of Trsp gene is partially compensated by Nrf2. (A) Peripheral blood counts of mice at 4 weeks after the final pI-pC injection. RBC, red blood cell; Hb, hemoglobin; HCT, hematocrit; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; WBC, white blood cell; PLT, platelet. *P < .01 and **P < .001 compared with values obtained from Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del mice. (B) Hct kinetics of mice treated with pI-pC. The day of the first pI-pC injection is depicted as 0. (C) Plasma indirect bilirubin levels were determined at 4 weeks after final pI-pC injection. Horizontal lines represent average values in each genotype (*P < .05; **P < .01). (D-K) Peripheral blood smears of mice at 4 weeks after the final pI-pC injection were stained with Wright-Giemsa (D-G) or new methylene blue (H-K). Arrows, white arrowheads, and black arrowheads indicate the poikilocytes, immature erythrocytes with basophilic cytoplasm, and erythrocytes with Howell-Jolly body, respectively.

The dramatic decrease in Hct levels of Nrf2:Trsp double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice was confirmed in a time-course study. Hct levels were measured manually in blood collected from the tail vein by centrifugation in microhematocrit tubes (see “Hematological analysis”). Values were obtained every week until 4 weeks after the final pI-pC injection (Figure 2B). While Hct of Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice decreased slightly compared with control (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del) mice, the Hct of Nrf2:Trsp double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice markedly decreased compared with that of Nrf2-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del) and Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice after the pI-pC treatment. These results indicate that the principle changes arising from selenoprotein deficiency in hematopoietic cells occurs in the RBC population.

We also found that 4 weeks after the final pI-pC injection, the indirect bilirubin levels in the blood plasma of Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice was significantly elevated compared with that of control (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del) mice (Figure 2C). At this time point, the mean corpuscular volume was increased in Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice (Figure 2A), and we surmised that the appearance of immature erythrocytes in peripheral blood may be the reason for this increase.

Consistent with these observations, Wright-Giemsa staining of peripheral blood cells showed that, while mature erythrocytes could be observed in control mice (Figure 2D), a substantial number of degraded erythrocytes (Figure 2E arrows) and immature erythrocytes with basophilic cytoplasm (Figure 2E white arrowheads) occurred in Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice (Figure 2E). These findings strongly argue that the absence of selenoproteins results in RBC lysis, leading to an increased production of immature erythrocytes.

Importantly, the indirect bilirubin levels of Nrf2:Trsp double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice was elevated beyond that of Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice, reaching almost 3 times the level of control (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del) mice (Figure 2C). Although there was no apparent abnormality in the blood of Nrf2-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del) mice (Figure 2F), a large number of degraded erythrocytes (Figure 2G arrows) and erythrocytes with Howell-Jolly body (Figure 2G black arrowheads) were observed in the blood smears of Nrf2:Trsp double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice, in addition to immature erythrocytes. Consistent with the severity of anemia, the reticulocyte counts in the peripheral blood of Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice were increased compared with that of control (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del) mice (Figure 2H-I). Moreover, the reticulocyte counts in peripheral blood of Nrf2:Trsp double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice were greatly increased despite no change in those of Nrf2-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del) mice (Figure 2J-K). These observations indicate that selenoproteins and Nrf2 help protect against RBC lysis and their absence presumably leads to enhanced erythrogenesis as a means to compensate for the loss of mature erythrocytes.

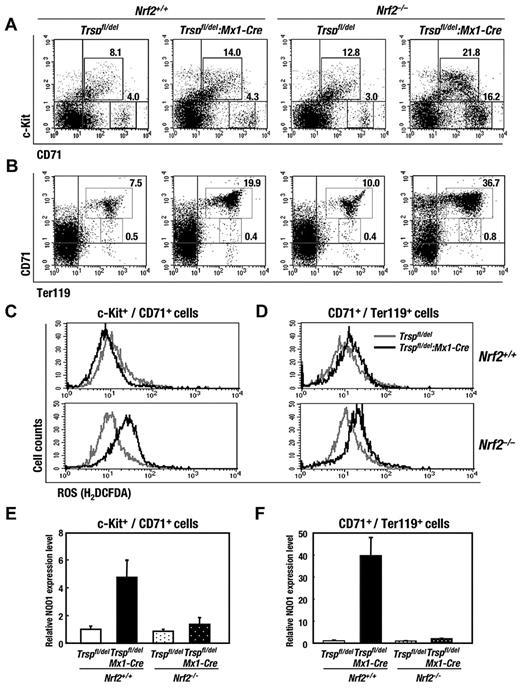

Trsp and Trsp-Nrf2 double-knockout mice have increased numbers of erythroblasts

Analysis of bone marrow cells by flow cytometry showed that the number of c-Kit+/CD71+ cells, which correspond to erythroid progenitors, increased in the absence of Nrf2 and Trsp (Figure 3A), and the number of CD71high/Ter119med/high cells, which correspond to proerythroblasts and basophilic erythroblasts,26 increased approximately 2.5 and 5 times in Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice and Nrf2:Trsp double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice, respectively, relative to that of control (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del) mice (Figure 3B). Of note, the expected number of CD71med/Ter119high cells, corresponding to polychromatophilic and orthochromatophilic erythroblasts,26 were observed in Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice and Nrf2:Trsp double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice. These observations support the contention that ongoing hemolytic anemia stimulates the increased production of erythroid progenitors in bone marrow, because the differentiation of CD71high/Ter119high cells to CD71–/Ter119high cells is a key step toward producing mature erythrocytes.

Nrf2 reduces the erythroid phenotype of Trsp-deficient mice. (A-B) Flow cytometric analysis of immature-erythroid (c-Kit+/CD71+) and mature-erythroid (CD71+/Ter119+) lineages in bone marrows, respectively. Representative data are presented from more than 3 independent experiments. Frequencies of cells in the indicated fraction are shown in the panels. (C-D) ROS production in c-Kit+/CD71+ (C) and CD71+/Ter119+ cells (D) of Trspfl/del and Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre mice on Nrf2+/+ (top) or Nrf2–/– (bottom) background. (E-F) Expressions of Nrf2 target gene mRNA levels in c-Kit+/CD71+ (E) and CD71+/Ter119+ cells (F) were examined by real-time RT-PCR. Ribosomal 18S subunit was used as an internal control.

Nrf2 reduces the erythroid phenotype of Trsp-deficient mice. (A-B) Flow cytometric analysis of immature-erythroid (c-Kit+/CD71+) and mature-erythroid (CD71+/Ter119+) lineages in bone marrows, respectively. Representative data are presented from more than 3 independent experiments. Frequencies of cells in the indicated fraction are shown in the panels. (C-D) ROS production in c-Kit+/CD71+ (C) and CD71+/Ter119+ cells (D) of Trspfl/del and Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre mice on Nrf2+/+ (top) or Nrf2–/– (bottom) background. (E-F) Expressions of Nrf2 target gene mRNA levels in c-Kit+/CD71+ (E) and CD71+/Ter119+ cells (F) were examined by real-time RT-PCR. Ribosomal 18S subunit was used as an internal control.

Contrary to the clear changes observed in the erythroid lineage, practically no change was detected in the granulo/monocytic (Gr1+/Mac1+ and Gr1–/Mac1+; supplemental Figure 2A) or mature megakaryocytic (CD61+/CD41+; supplemental Figure 2B) populations. In this regard, we found that the number of CD61low/CD41– cells (indicated by the region enclosed by white lines in supplemental Figure 2B), which include not only premature megakaryocytes but also osteoclasts and endothelial cells,27,28 decreased in Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice and Nrf2:Trsp double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice. CD61+/CD41+ mature megakaryocyte numbers did not change between any of the genotypes, suggesting that the impact of selenoprotein deficiency may be limited to premature megakaryocytes. No change in the number of LSK cells (c-Kit+/ScaI+/Linage–) in bone marrow, which include multipotential hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells, was observed between any of the genotypes (supplemental Figure 2D).

It is worth highlighting that there was a significant increase in the ROS levels of erythroid progenitor cells (c-Kit+/CD71+) between Trsp:Nrf2 double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) and Nrf2-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del) mice but not between Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) and control (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del) mice (Figure 3C). The ROS levels of proerythroblasts and basophilic erythroblasts (CD71+/Ter119+) showed a greater increase between Trsp:Nrf2 double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) and Nrf2-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del) mice compared with the relative levels of ROS seen in Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) and control (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del) mice (Figure 3D). In contrast, no change of ROS level was detected in granulo/monocytic cells (Gr1+/Mac1+), megakaryocytes (CD61+/CD41+), T cells (CD3+), or LSK cells (supplemental Figure 3A-D).

In the c-Kit+/CD71+ and CD71+/Ter119+ cells of Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice, the expression levels of NQO1 increased in an Nrf2-dependent manner (Figure 3E-F), similar to what was observed earlier in whole bone marrow cells (Figure 1E). Furthermore, these results indicate that Nrf2 gene induction can compensate for the defects in ROS scavenging caused by the loss of selenoproteins in erythrocytes. Thus, Nrf2 is critical for sustaining erythropoiesis in the absence of selenoproteins.

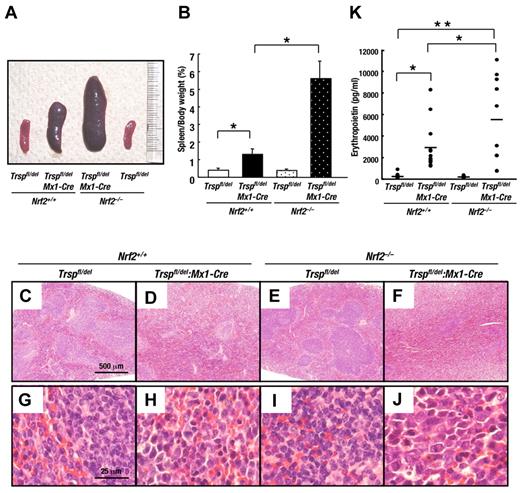

Consistent with the degree of anemia and in accordance with our expectations, the severity of splenomegaly was notably greater in Nrf2:Trsp double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice relative to Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice (Figure 4A-B). Microscopic analyses revealed expansion of red pulp and an obscuring of the splenic architecture in Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice (Figure 4F). In contrast, whereas the spleens of Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice showed expansion of red pulp, the splenic architecture remained intact (Figure 4D). Spleens from mice of the other genotypes did not show similar abnormalities (Figure 4C,E). Under higher magnification, we also observed a massive increase in immature nucleated erythroblasts in the spleen of Nrf2:Trsp double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice (Figure 4J), which was less obvious in the spleens of the other genotype mice (Figure 4G-I). The erythropoietin levels in the blood plasma of Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice were significantly elevated compared with that of control (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del) mice (Figure 4K), and importantly the erythropoietin levels of Nrf2:Trsp double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice were elevated yet further relative to Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice and nearly twice higher than that of control (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del) mice (Figure 4K). These results unequivocally demonstrate that the fragility of the erythrocytes in circulation is offset by a compensatory increase in their regeneration, through a marked increase in erythroblasts numbers.

Removal of Nrf2 exacerbates compensatory erythroid hyperplasia in Trsp-deficient mice. (A) Macroscopic appearance of spleens at 4 weeks after the final pI-pC injection. (B) Spleen/body weight ratios of Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del (n = 7), Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre (n = 7), Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del (n = 8), and Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del::Mx1-Cre (n = 10; *P < .001). (C-J) Histopathological examination of spleens at 4 weeks after the final pI-pC injection. Scale bars correspond to 500 μm (C-F) and 25 μm (G-J), respectively. (K) Serum erythropoietin levels were determined at 4 weeks after final pI-pC injection. Horizontal lines represent average values in each genotype (*P < .05; **P < .001).

Removal of Nrf2 exacerbates compensatory erythroid hyperplasia in Trsp-deficient mice. (A) Macroscopic appearance of spleens at 4 weeks after the final pI-pC injection. (B) Spleen/body weight ratios of Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del (n = 7), Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre (n = 7), Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del (n = 8), and Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del::Mx1-Cre (n = 10; *P < .001). (C-J) Histopathological examination of spleens at 4 weeks after the final pI-pC injection. Scale bars correspond to 500 μm (C-F) and 25 μm (G-J), respectively. (K) Serum erythropoietin levels were determined at 4 weeks after final pI-pC injection. Horizontal lines represent average values in each genotype (*P < .05; **P < .001).

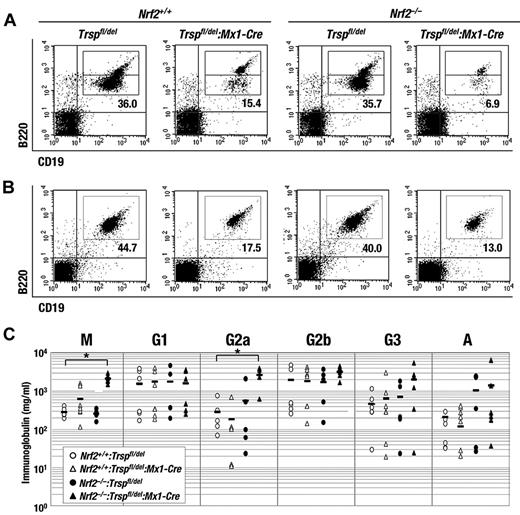

Removal of Nrf2 decreases B-cell number but promotes immunoglobulin production in Trsp-deficient mice

Flow cytometric analysis of bone marrow cells also showed that the number of B cells (B220+/CD19+) in Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice decreased to approximately 30% that of control (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del) mice (Figure 5A). Although no apparent defect was observed in the B cells of Nrf2-knockout mice, the number of B cells in Nrf2:Trsp double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice was significantly decreased to approximately 10% that of control Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del mice (Figure 5A). Similarly, the number of splenic B cells in Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice also decrease to approximately 40% that of control, and the number of splenic B cells in Nrf2:Trsp double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice was dramatically decreased to approximately 30% that of control Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del mice (Figure 5B). These results suggest that Nrf2 has an important compensatory role in the homeostasis of B cells under conditions of selenoprotein deficiency. In contrast to B cells, no change in the number of T cells (CD3+) in bone marrow was observed between any of the genotypes (supplemental Figure 2C).

Removal of Nrf2 accelerates the reduction of B-cell number caused by Trsp gene loss but promotes immunoglobulin production. (A-B) Flow cytometric analysis of B cells (B220+/CD19+) in bone marrow (A) and spleen (B) of Trspfl/del and Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre mice on an Nrf2+/+ or Nrf2–/– background. Representative data are presented from more than 3 independent experiments. (C) Serum immunoglobulin concentrations from Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del (open circles), Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre (open triangles), Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del (closed circles), and Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre (closed triangles). Horizontal bars indicate average means (*P < .005).

Removal of Nrf2 accelerates the reduction of B-cell number caused by Trsp gene loss but promotes immunoglobulin production. (A-B) Flow cytometric analysis of B cells (B220+/CD19+) in bone marrow (A) and spleen (B) of Trspfl/del and Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre mice on an Nrf2+/+ or Nrf2–/– background. Representative data are presented from more than 3 independent experiments. (C) Serum immunoglobulin concentrations from Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del (open circles), Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre (open triangles), Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del (closed circles), and Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre (closed triangles). Horizontal bars indicate average means (*P < .005).

The changes in the B-cell lineage prompted us to investigate serum immunoglobulin concentrations by enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay. Surprisingly, some classes of immunoglobulin (eg, IgM and IgG2a) were increased rather than decreased in Nrf2:Trsp double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice (Figure 5C). It was observed that in bone marrow the B220low population was decreased more than the B220high population (Figure 5A). Because increased B220 expression relates to B-cell differentiation,25 we investigated whether a defect in B-cell differentiation can be explained by the accumulation of ROS. However, no detectable change in ROS levels occurred in either B cell populations from bone marrow (supplemental Figure 4A-B) or spleen (supplemental Figure 4C) across all of the genotypes, suggesting that the source of the immunoglobulin changes is independent of ROS. Overall, the results imply that although loss of selenoproteins and Nrf2 reduces the number of B cells, it can also promote B-cell activation in a ROS-independent manner.

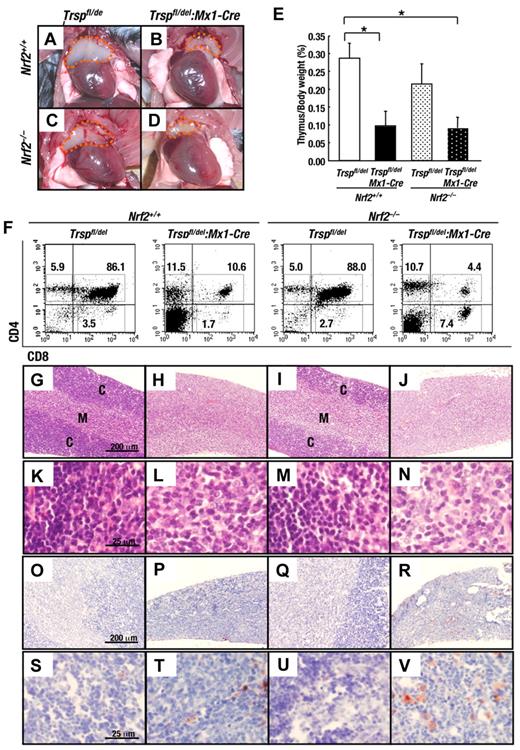

Removal of Trsp provokes thymus atrophy

We also found that the thymus size of both Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre; Figure 6B) and Nrf2:Trsp double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre; Figure 6D) mice was markedly decreased compared with that of control mice (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del; Figure 6A). In contrast, the thymus size of Nrf2-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del) mice (Figure 6C) was comparable to that of the control (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del) mice. The thymus size of Nrf2:Trsp double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice appears similar to that of Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice (Figure 6E). Although the number of T cells was comparable between the bone marrow of Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice and Nrf2:Trsp double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice (supplemental Figure 2C), CD4+/CD8+ cells from the thymus of Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice were decreased to approximately 12% that of control (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del) mice (Figure 6F). These observations could suggest that selenoproteins are dispensable for immature T cells in bone marrow but not for maturing T cells within the thymus. Although no apparent defects were observed in the CD4+/CD8+ cells of Nrf2-knocout mice, the number of CD4+/CD8+ cells in Nrf2:Trsp double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice was dramatically decreased to approximately 5% that of control Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del mice (Figure 6F). However, no changes in the ROS levels of CD4+/CD8+ thymus cells were observed between any of the genotypes (supplemental Figure 5). Our results imply that selenoproteins and Nrf2 may be essential for T-cell differentiation in the thymus in a ROS-independent manner.

Removal of Trsp provokes thymus atrophy. (A-D) Appearance of thymus from Trspfl/del and Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre mice on an Nrf2+/+ or Nrf2–/– background at 4 weeks after the final pI-pC injection. Orange dot lines indicate thymus. (E) Thymus/body weight ratios of Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del (n = 6), Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre (n = 5), Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del (n = 5), and Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre (n = 7; *P < .05). (F) Flow cytometric analysis of T cells (CD4+/CD8+) in thymus of Trspfl/del and Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre mice on an Nrf2+/+ or Nrf2–/– background. Representative data are presented from more than 3 independent experiments. (G-V) Histological examination of thymus from Trspfl/del and Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre mice on an Nrf2+/+ or Nrf2–/– background with hematoxylin and eosin staining (G-N) or Oil Red O staining (O-V). Scale bars correspond to 200 μm (G-J and O-R) and 25 μm (K-N, S-V), respectively. C, cortex; M, medulla.

Removal of Trsp provokes thymus atrophy. (A-D) Appearance of thymus from Trspfl/del and Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre mice on an Nrf2+/+ or Nrf2–/– background at 4 weeks after the final pI-pC injection. Orange dot lines indicate thymus. (E) Thymus/body weight ratios of Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del (n = 6), Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre (n = 5), Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del (n = 5), and Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre (n = 7; *P < .05). (F) Flow cytometric analysis of T cells (CD4+/CD8+) in thymus of Trspfl/del and Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre mice on an Nrf2+/+ or Nrf2–/– background. Representative data are presented from more than 3 independent experiments. (G-V) Histological examination of thymus from Trspfl/del and Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre mice on an Nrf2+/+ or Nrf2–/– background with hematoxylin and eosin staining (G-N) or Oil Red O staining (O-V). Scale bars correspond to 200 μm (G-J and O-R) and 25 μm (K-N, S-V), respectively. C, cortex; M, medulla.

Histological analysis of the thymus from Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del and Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del mice revealed a dark staining cortex and more lightly staining medulla (Figure 6G,I) compared with Trsp-deficient mouse thymus (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre; Figure 6H). The thymic cortex and medulla were only poorly demarcated in the Nrf2:Trsp double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice (Figure 6J). At higher magnifications of the cortex, we noticed a significant decrease in the density of hematoxylin-positive nuclei (ie, lymphocytes) in Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre mice in the presence or absence of Nrf2 (Figure 6L,N) compared with Trsp-positive mouse thymus (Figure 6K,M). Moreover, when we examined the thymus by Oil Red O staining, which is used to visualize lipids, we found an increase in adipocyte number in the thymus of Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice that became even more pronounced in Nrf2:Trsp double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice (red color cells in Figure 6O-V). Because thymus atrophy, accompanied by an increase in adipocytes, is frequently observed in aging, these observations support the idea that loss of antioxidant activity leads to thymus involution and immunological imbalance.

Collectively, our results strongly argue for a differential sensitivity of hematopoietic cells to the loss of selenoprotein function with (1) erythrocytes showing a decrease in viability leading to hemolytic anemia in a ROS dependent manner, (2) lymphoid T and B cells showing decreased numbers independent of ROS formation, and (3) macrophage, megakaryocytes, and multipotential hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells remaining unaffected by the loss of selenoproteins. Nrf2 has a vital role in protecting erythrocytes against ROS production and lysis. With the loss of both selenoproteins and Nrf2 hemolytic anemia, ROS production and erythropoiesis is markedly elevated.

Discussion

The first report linking selenium deficiency to anemia showed that cattle grazing on peaty muck soils in the Florida Everglades often develop anemia, which could be effectively treated by selenium supplementation of the diet.29 Subsequent reports have shown that low serum selenium levels may also be associated with anemia in humans.18-20 This study strongly supports the contention that selenium deficiency is a causative factor in anemia and can be explained by the loss of selenoprotein function, which is important for maintaining the oxidative status of erythrocytes. In the absence of selenoproteins, the Nrf2 gene battery inhibits ROS production and lysis, demonstrating the functional overlap of these antioxidant systems in preventing hemolytic anemia.

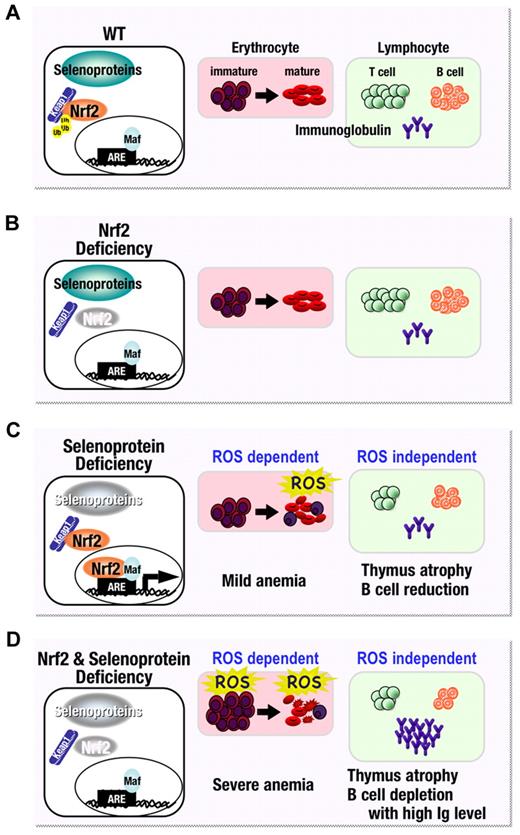

Nrf2 was originally discovered as a homologue of the NF-E2 p45 protein, which binds to the β-globin gene enhancer and acts as an important transcription factor in erythroid and megakaryocytic lineages.30,31 Since then, numerous reports have documented the role of Nrf2 in the stress response of various tissues.32-35 The physiological significance of Nrf2 in hematopoietic tissues has remained largely unexplored. This is partly because original studies found no overt hematopoietic abnormalities,36 even in combination with knockout of the p45 NF-E2 gene.37 Therefore, not much attention has been given to the importance of Nrf2 in anemia, although signs of anemia have been found in aged Nrf2 knockout mice.38 This study provides clear evidence that Nrf2 is important for the redox homeostasis of erythrocytes under pro-oxidant stress conditions. As summarized in Figure 7, in this study, we created a pro-oxidant environment in blood cells by disrupting selenoprotein synthesis and unequivocally demonstrate the role Nrf2 plays in maintaining redox homeostasis of erythrocytes.

Model for the effect of Nrf2 and selenoprotein loss on hematopoietic cells. (A) Under normal conditions, selenoproteins maintain redox balance while the Nrf2 gene battery is repressed by Kelch-like ECH-associated protein–mediated proteasomal degradation. (B) Therefore, in the steady state, oxidative homeostasis is maintained even in the absence of Nrf2. (C) In the case of a pro-oxidant environment, created in blood by disrupting selenoprotein synthesis, Nrf2 is activated and helps maintain homeostasis in immature erythrocytes. However, Nrf2 cannot fully compensate for loss of the selenoproteins-mediated antioxidant machinery, especially in mature erythrocytes, and therefore mice lacking selenoprotein activity suffer from mild anemia. On the other hand, the impairment seen in lymphocytes is ROS independent. (D) Since selenoprotein activities and the Nrf2 gene battery co-operatively maintain the oxidative homeostasis of immature erythrocytes, combined disruption of these 2 antioxidant systems leads to severe anemia. Ig, immunoglobulin.

Model for the effect of Nrf2 and selenoprotein loss on hematopoietic cells. (A) Under normal conditions, selenoproteins maintain redox balance while the Nrf2 gene battery is repressed by Kelch-like ECH-associated protein–mediated proteasomal degradation. (B) Therefore, in the steady state, oxidative homeostasis is maintained even in the absence of Nrf2. (C) In the case of a pro-oxidant environment, created in blood by disrupting selenoprotein synthesis, Nrf2 is activated and helps maintain homeostasis in immature erythrocytes. However, Nrf2 cannot fully compensate for loss of the selenoproteins-mediated antioxidant machinery, especially in mature erythrocytes, and therefore mice lacking selenoprotein activity suffer from mild anemia. On the other hand, the impairment seen in lymphocytes is ROS independent. (D) Since selenoprotein activities and the Nrf2 gene battery co-operatively maintain the oxidative homeostasis of immature erythrocytes, combined disruption of these 2 antioxidant systems leads to severe anemia. Ig, immunoglobulin.

We envisage that our data have particular relevance to individuals with mutation in the glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) gene, which provides natural protection against malaria infection. G6PD is the first enzyme of the pentose phosphate pathway and provides reducing power to cells in the form of NAD(P)H. This in turn allows reduction of glutathione and thioredoxin, intracellular thiols required for the activity of many selenoproteins and proteins of the Nrf2 gene battery. Not surprisingly, mutations in the G6PD gene exacerbate the pro-oxidant environment of malaria-infected erythrocytes. Individuals deficient in G6PD are mostly asymptomatic, but oxidative stress triggered by drugs, including antimalarials, manifests as acute hemolysis and anemia.39 An important observation is that, similar to the G6PD mutations, the effect of both selenoprotein and Nrf2 deficiency is particularly prominent in erythrocytes, which could be as a result of the heme- and oxygen-rich environment that together promote ROS production.40

A further point of note is the fact that Nrf2 activation could effectively suppress ROS production in the bone marrow and erythroid cells of selenoprotein-deficient mice, thereby improving Hct levels. It was only upon the loss of both antioxidant systems that severe red cell lysis was observed coupled with greatly elevated serum bilirubin levels. Clearly, co-operativity exists between these 2 antioxidant systems in prolonging erythrocyte survival in vivo. In this regard, it should also be noted that although intercellular ROS levels are almost completely suppressed in the early stages of erythroid maturation in Trsp conditionally knockout mice, mild anemia and hemolysis developed at later stages in the mice, suggesting that Nrf2 is unable to fully compensate for loss of the selenoprotein antioxidant machinery.

Loss of selenoproteins in young adult mice (16-18 weeks old) was found to cause thymus atrophy, an event often considered as an age-related process. Significant consensus exists about the contribution of oxidative stress and oxygen radicals to aging.4 Therefore, it is interesting to note the marked decrease in the size of the thymus of Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) and Nrf2:Trsp double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice. In agreement with this observation, specific removal of Trsp gene from T cells by Lck-driven Cre expression caused suppression of T-cell proliferation in response to T-cell receptor stimulation.41 Although we could not find a difference in thymus size between Trsp-deficient (Nrf2+/+:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice and Nrf2:Trsp double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice, removal of Nrf2 slightly exacerbated the destruction of thymus architecture and adipose degeneration provoked by selenoprotein deficiency. These observations demonstrate the important antioxidant function contributed by the Nrf2-regulated cytoprotective enzymes.

An unexpected finding was the elevated levels of several immunoglobulin types (eg, IgM and IgG2a) in Nrf2:Trsp double-knockout (Nrf2–/–:Trspfl/del:Mx1-Cre) mice despite the decrease in B-cell number in bone marrow and spleen. This observation could be explained by autonomous hyperactivation of B cells in the presence of increased ROS. This idea is consistent with previous studies showing that aged Nrf2-knockout mice develop lupus-like autoimmune nephritis.42 Atrophy of the thymic cortex and reduced B cells with increased serum immunoglobulin levels are all found as part of “stresses” associated with high cortisol levels. However, serum corticosterone levels were not change between any of genotypes (supplemental Figure 6). Therefore, the observed phenotypes are unlikely due to a corticosterone-mediated mechanism.

Finally, our flow cytometric analysis results showed that Nrf2 is important for eliminating intercellular ROS. However, in addition to antioxidant enzymes, many Nrf2 target genes, such as glutathione S-transferase family members, NQO1, and cell-surface transporters, also retain important detoxifying functions.43 Therefore, the role played Nrf2 when selenoprotein function is lost may not be limited to the eradication of ROS species. Under such situation, enzymes in the Nrf2 gene battery may also act to eliminate and detoxify secondary metabolites. We believe that elucidation of the precise contribution of Nrf2 to the erythroid and lymphoid functions is now emerging as an important topic in the molecular hematology field.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Hozumi Motohashi, Akihiko Muto, and Fumiki Katsuoka for advice and discussion. We also thank Ms Eriko Naganuma for technical assistance. We thank the Biomedical Research Core of Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine for technical support.

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Creative Scientific Research, Scientific Research on Priority Areas, and Scientific Research from JSPS; Target Protein Program from MEXT; Tohoku University Global COE Program for Conquest of Signal Transduction Diseases with “Network Medicine,” the Naito Foundation; and the Takeda Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: Y.K. designed and executed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; T.S. designed experiments and wrote the manuscript; R.S. wrote the manuscript; V.P.K. designed experiments and wrote the manuscript; and M.Y. provided direction and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Masayuki Yamamoto, Department of Medical Biochemistry, Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine, 2-1 Seiryo-cho, Aoba-ku, Sendai 980-8575, Japan; e-mail: masiyamamoto@med.tohoku.ac.jp.

References

Author notes

Y.K. and T.S. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal