In this issue of Blood, Hosking and colleagues report the lack of correlation between genetic variants within the MHC and the risk of ALL.1

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common pediatric cancer. It is a biologically heterogeneous disease with B-cell precursor ALL as the most common subtype accounting for ∼ 70% of childhood ALL. There is now conclusive evidence that the risk of ALL has an inherited genetic component.2-4 There has been considerable interest in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) locus on chromosome 6p21 due to the proposition that immune dysfunction or delayed infection has a role in ALL etiology. However, the results have been inconsistent with different class I and class II alleles implicated. Possible reasons for the inconsistencies include study design issues (limited sample sizes, confounded by population stratification), multiple testing, and disease definition of ALL. Hosking et al overcome several of these issues in their study. Using existing genotype data from a genome-wide association (GWA) study of ALL and imputed data based on the HapMap, they evaluated more than 8000 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the MHC region, spanning 4.5 Mb in 824 B-cell precursor ALL cases and 4737 controls. Both single SNP analyses as well as haplotype analyses lacked any evidence of association. The authors also estimated 2- and 4-digit human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles from the SNP genotypes and still found little evidence of association with B-cell precursor ALL risk, especially after accounting for multiple testing (see figure).

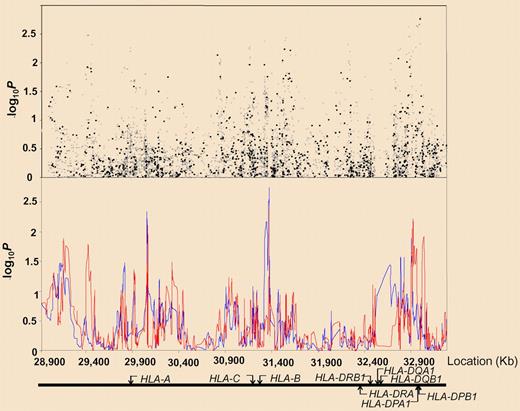

Association between SNPs and haplotypes mapping to 6p21 and BCP-ALL risk. The x-axis represents the position of each SNP; the y-axis, P values on a minus logarithmic scale. Cochran-Armitage trend test statistics are shown in black for directly genotyped SNPs and in gray for imputed SNPs in the top panel. Lines in the bottom panel correspond to haplotype test statistics: blue defined by 5 SNPs and red by 12 SNPs. Relative positions of the major HLA genes are also shown. Chromosomal coordinates were derived from the National Center for Biotechnology Information, build 36. See the complete figure in the article by Hosking et al beginning on page 1633.

Association between SNPs and haplotypes mapping to 6p21 and BCP-ALL risk. The x-axis represents the position of each SNP; the y-axis, P values on a minus logarithmic scale. Cochran-Armitage trend test statistics are shown in black for directly genotyped SNPs and in gray for imputed SNPs in the top panel. Lines in the bottom panel correspond to haplotype test statistics: blue defined by 5 SNPs and red by 12 SNPs. Relative positions of the major HLA genes are also shown. Chromosomal coordinates were derived from the National Center for Biotechnology Information, build 36. See the complete figure in the article by Hosking et al beginning on page 1633.

Although the reported findings are negative, they are important. First, with more than 800 cases and 4700 controls, this study is sufficiently powered to identify common variants with modest effects, even after adjusting for multiple testing. Second, this study focused on only 1 ALL subtype, B-cell precursor ALL. Although this limits generalizability of the findings to other subtypes, this reduces heterogeneity and therefore strengthens statistical power. Finally, this study was able to rule out confounding from population stratification or cryptic relatedness due to the available genotype data from the GWA study. Most candidate-gene association studies are only able to use self-reported race or ethnicity that can be inadequate. However, with the use of the GWA data, one can estimate race from the observed genetic data thereby providing an unbiased estimate of race.5

Do the results of Hosking et al mean that we can rule out any role of the MHC region on the risk of B-cell precursor ALL? Unfortunately, no. This study touches on only one aspect of the genomic complexity in the region by providing conclusive evidence that common genetic variants within the region lack any association with risk. However, other possible mechanisms may still exist, including interactions (eg, interactions between MHC variants and variants located on other chromosomes), epigenetics (eg, methylation of genes), or structural changes (eg, insertions or deletions of chromosomal regions). Further work still needs to be done to determine what role, if any, the MHC region has in ALL risk, but the reporting of negative results from strong studies is a positive thing.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal