Abstract

Osteoblasts play a crucial role in the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niche; however, an overall increase in their number does not necessarily promote hematopoiesis. Because the activity of osteoblasts and osteoclasts is coordinately regulated, we hypothesized that active bone-resorbing osteoclasts would participate in HSC niche maintenance. Mice treated with bisphosphonates exhibited a decrease in proportion and absolute number of Lin−cKit+Sca1+ Flk2− (LKS Flk2−) and long-term culture–initiating cells in bone marrow (BM). In competitive transplantation assays, the engraftment of treated BM cells was inferior to that of controls, confirming a decrease in HSC numbers. Accordingly, bisphosphonates abolished the HSC increment produced by parathyroid hormone. In contrast, the number of colony-forming-unit cells in BM was increased. Because a larger fraction of LKS in the BM of treated mice was found in the S/M phase of the cell cycle, osteoclast impairment makes a proportion of HSCs enter the cell cycle and differentiate. To prove that HSC impairment was a consequence of niche manipulation, a group of mice was treated with bisphosphonates and then subjected to BM transplantation from untreated donors. Treated recipient mice experienced a delayed hematopoietic recovery compared with untreated controls. Our findings demonstrate that osteoclast function is fundamental in the HSC niche.

Introduction

The identification of the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niche as the particular microenvironment in the bone marrow (BM) cavity that controls HSC fate was initially proposed by Scofield in 1978.1 Extensive research has identified several cell types, such as endothelial cells,2-4 fibroblasts,5 adipocytes,6,7 and osteoblasts, as important constituents of the HSC niche. The most thoroughly investigated are the osteoblasts, with studies showing that increasing their number is associated with HSC expansion.8,9 Recent work has shown that hematopoietic cells are important contributors to the osteoblast differentiation and activity. Jung et al demonstrated that HSCs can contribute actively to their own niche by controlling mesenchymal stem cell to osteoblast differentiation.10 Similarly, macrophages have been demonstrated as critical to both osteoblast activity and the formation of an optimal HSC niche.11,12 Furthermore, mesenchymal stem cells themselves have also been identified as unique contributors to the HSC niche as purified HSCs have been shown to home to nestin-positive mesenchymal stem cells.13

Our previous study using strontium to increase osteoblast numbers failed to show a concomitant increase in HSC number.14 These findings were unexpected and indicated that either different types of osteoblasts were formed in response to strontium or that the activity of other cell types in the HSC niche was required. Osteoblast turnover is intimately linked to the process of bone remodeling whereby the bone-forming osteoblasts cooperate with bone-resorbing osteoclasts to maintain the integrity of the bone and the BM cavity. In physiologic conditions, bone degradation precedes bone formation in a process termed “coupling.”15 Because strontium has also been reported to decrease osteoclast activity, we hypothesized that the ineffectiveness of strontium in the HSC niche could be attributed to the inhibition of osteoclastic bone resorption.

Several lines of evidence indicate that functional osteoclasts play a role in the regulation of the HSC microenvironment. The degradation of the bone matrix by osteoclasts releases numerous growth factors into the BM cavity, including transforming growth factor-β, insulin growth factors, and bone morphogenetic proteins. These molecules have been described as regulators of HSC and hematopoietic progenitor proliferation and survival, although it should be noted that many of these studies have only been performed in vitro.16-19 Furthermore, osteoclasts release high amounts of the hydroxyapatite-bound calcium, which has been previously shown to be an important regulator of HSC retention in close physical proximity to the endosteal surface, interacting with the calcium-sensing receptors expressed on HSCs.20 More importantly, the direct involvement of osteoclasts in the regulation of hematopoiesis has been demonstrated by the observation that they actively participate in the mobilization of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells from the BM to the circulation, both in homeostatic and stress-induced conditions, through cathepsin K-mediated cleavage of SDF-1.21

We hypothesized that osteoclast-mediated bone resorption is a fundamental process for the function of the HSC niche. To address this question, we tested the effects of bisphosphonates, a group of drugs that inhibit bone resorption by selective absorption to mineral surfaces and subsequent internalization by bone-resorbing osteoclasts. In the current study, we used the bisphosphonate alendronate (ALN), which is currently one of the most widely used antiresorptive agent for the treatment of several bone loss related disorders, such as osteoporosis22 and Paget disease of bone.23 We observed that ALN-mediated inhibition of osteoclastic bone resorption reduced the number of primitive HSCs, favoring the expansion of the hematopoietic progenitors. In addition, ALN-treated recipients experienced a delayed reconstitution of hematopoiesis. The administration of ALN abolished the ability of parathyroid hormone (PTH) to increase the primitive HSC pool size and to enhance the capacity of HSCs to reconstitute irradiated recipients. Our findings demonstrate that the osteoclast function is fundamental in the HSC niche.

Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Olac. C57BL/6 CD45.1 (Ly5.1) and C57BL/6 Thy1.1 x C57BL/6 CD45.2 congenic mice were bred and maintained in the specific pathogen-free Central Biomedical Service, Imperial College, Hammersmith Campus, London, United Kingdom. All animals used were at the age of 8 to 12 weeks. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Home Office Animals Act of 1986 (United Kingdom).

Administration of bone remodeling agents

Eight- to 12-week-old C57BL/6 female mice received weekly intraperitoneal injections of 100 μL of 50 μg/mL ALN diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; equivalent to 250 μg/kg per week) or PBS alone as vehicle control for 4 weeks. The schedule dosing of ALN has been previously shown to suppress bone resorption.24 Salmon calcitonin (T366 Sigma-Aldrich) was administered intraperitoneally (5 μg/kg) 3 days/week for a total of 21 days.25,26 For the in vivo administration of PTH, the Alzet osmotic minipumps model 1004 (Charles River) were used. The model 1004 was chosen because it has been designed to continuously infuse the compound at a rate of 0.11 μL/hour for 4 weeks. The pumps were aseptically filled with 100 μL of 0.61 mg/mL rat PTH 1-34 (Bachem) diluted in sterile PBS with 10mM of acetic acid, pH 7.42, thus providing 0.07 μg/0.11 μL/hour (equivalent to 80 μg/kg per day) 48 hours before implantation and placed at 37°C until use. Vehicle control pumps containing equivalent volume of 10mM acetic acid in sterile PBS, pH 7.42, were also prepared. Ten-week-old C57BL/6 CD45.1/2 female mice were anesthetized with isoflurane administration via a gas anesthetic machine, and the pumps were implanted subcutaneously into the back of the neck of mice. The incision was closed with wound sutures. Mice were also injected with Baytril and Rimadyl for the prevention of infections and the relief of the postsurgical pain, respectively. After the implantation of the pump, animals were carefully monitored for any signs of stress, bleeding, pain, or abnormal behavior.

Serum protein measurement

Blood samples were obtained by cardiac puncture from killed animals and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. Samples were centrifuged at 700g for 5 minutes and isolated serum was stored at −80°C until use. Osteocalcin concentration was quantified by the mouse Osteocalcin ELISA kit (Biomedical Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For the measurement of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase form 5b (TRAPCP-5b), the mouse TRAP Assay (IDS Ltd, Immunoassays) was used. To verify the delivery of the rat PTH 1-34 by the osmotic minipumps, the concentration of rat PTH 1-34 was determined in the blood serum 2 and 4 weeks after the implantation using the rat PTH immunoradiometric assay kit (Immutopics).

Histomorphometry

Bone histomorphometry was performed according to standard procedures as previously described.14 Briefly, the bones were fixed in 4% vol/vol formalin/saline (pH 7.4) and embedded in methyl methacrylate. Longitudinal sections (4 μm) were then prepared and stained with toluidine blue. Osteoblasts were identified as plump cells lining the bone surface. Osteoclasts were identified as flat cells on the bone surface characterized by multiple heterochromatic nuclei. Osteoblasts and osteoclasts were counted in 5 sections per bone with an intersection distance of 50 μm. The enumeration was performed in the region one section below the growth plate, including all trabecular bone, but not any cortical bone (using 20× objective). Two people, blinded to the source of the sections, counted the number of osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Bone histomorphometric variables were expressed according to the guidelines of the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research Nomenclature Committee.27 The following parameters were obtained: osteoblast number, osteoblast number per bone perimeter, osteoclast number, and osteoclast number per bone perimeter.

Micro-CT

Micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) analysis was partially performed by Kevin Mackenzie at the Histology and EM Core Facility of the University of Aberdeen, as previously described.24 In brief, tibias were placed vertically in a SkyScan 1072 X-ray Microtomograph (SkyScan), and images were obtained at 50 kV (197 μA) using a 0.5-mm aluminium filter. For each specimen, a series of 276 projection images (pixel = 5.05 μm, image size 1024 × 1024) were obtained with a rotation step of 0.67° between each image.28 The projection images were then reconstructed to give a stack of two-dimensional images, using Nrecon 1.4.4 (SkyScan), whereas three-dimensional modeling and analysis were then performed using CTAn software (Version 1.5.0.2; SkyScan). Trabecular bone distal to the growth plate was selected for analysis within a region of interest (excluding the cortical bone), starting at 100 μm (20 image slices) from the growth plate and extending 1.015 mm (200 image slices) for each tibia. The following bone morphometric parameters27 were obtained: tissue volume (TV), bone volume (BV), tissue surface, bone surface (BS), percentage of bone surface (BS/TV), percentage of bone volume (BV/TV), trabecular thickness, trabecular separation, trabecular number, and trabecular pattern factor.

Histochemistry

Skeletal specimens were fixed in 10% vol/vol formalin/saline and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut at 5-μm thickness on a Leica CM1900 cryostat (Leica Microsystems) and stained with Masson trichrome or TRAP staining and counterstained with methyl-green as stated, following the standard procedures.

CFU-C assay

BM cells from treated and untreated mice were assessed for colony-forming-unit-cell (CFU-C) frequency in complete MethoCult medium (M3434; StemCell Technologies), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Duplicate cultures were prepared for each sample and were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2 in air and more than or equal to 95% humidity. Colonies were scored 12 days after plating.

LTC-IC assay

Freshly isolated BM cells were seeded in 96-well plates in MyeloCult medium (M5300; StemCell Technologies) supplemented with 10μM hydrocortisone (StemCell Technologies) for the establishment of the feeder layers as previously described.14 After 2 weeks, a confluent adherent layer was formed and the cultures were irradiated with 15 Gy of γ-irradiation. BM cell suspensions from treated and untreated mice were then added to the stromal layers, and the cultures were further incubated for 4 weeks at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 with weekly half-medium change. The contents of each well were then plated in MethoCult medium. Twelve days after plating, the wells were scored as positive (≥ 1 CFU) or negative (no CFU) and the long-term culture–initiating cell (LTC-IC) frequencies were calculated by the method of maximum likelihood from the proportion of the wells that were negative according to the limiting dilution analysis.29

Flow cytometric (fluorescence-activated cell sorter) analysis

Peripheral blood samples were collected into blood buffer (PBS containing 100 U/mL heparin, 10mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) from mice at the time point indicated, and red blood cells (RBCs) were lysed using RBC lysis buffer. Cells were resuspended in PBS supplemented with 2% fetal calf serum and incubated for 5 minutes at room temperature with IgG from murine serum to block the Fc receptors and avoid nonspecific binding. A panel of fluorochrome-conjugated mAbs (as indicated in different assays) was then added for 30 minutes at room temperature. After washing with PBS, cells were analyzed using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo Version 7.0 software (TreeStar). Appropriate isotype controls were also included. All fluorochrome-conjugated Abs were purchased from BD Biosciences PharMingen.

For the immunophenotypical enumeration of HSCs, BM cells were stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated lineage antibodies (anti-CD3, anti-B220, anti-Ter-119, anti-Mac-1, and anti-Gr-1), fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-Sca-1, allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-c-kit, and phycoerythrin-Cy5-conjugated anti-Flk2 (BD Biosciences PharMingen). Primitive HSCs were identified as the Lin− Sca1+ c-kit+ Flk2− (LKS Flk2−) cell population.

Cell-cycle analysis

To assess the cell-cycle status of the primitive hematopoietic population, lineage-negative cells were purified from treated and untreated BM cells using the EasySep Mouse Hematopoietic Progenitor Cell Enrichment Kit (StemCell Technologies). Cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 2 mL of 70% cold ethanol, and kept overnight at 4°C. The next day, cells were washed twice with PBS before being stained with 40 μg/mL propidium iodide, which binds to DNA, 0.1 μg/mL fluorescein isothiocyanate as a protein dye, and 25μg/mL RNAse A (all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark.30,31 FlowJo Version 7.0 software was used for the analysis.

Bone marrow transplantation

For in vivo enumeration of HSCs, 2.5 × 106 CD45.2 BM cells were isolated from treated and untreated C57BL/6 mice and mixed with 2.5 × 106 CD45.1 cells from CD45.1 congenic mice. Cells were then intravenously injected into CD45.2/CD45.1 recipient mice that had been lethally irradiated with 1300 cGy of γ-irradiation. The frequency of the different cell populations was determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis at regular time intervals after transplantation in the peripheral blood (PB) of recipient mice by FACS analysis using phycoerythrin-CD45.1 and fluorescein isothiocyanate-CD45.2 antibodies (BD Biosciences PharMingen).

To assess the effect ALN in recipients, C57BL/6 mice were treated for 4 weeks with ALN. Each mouse was lethally irradiated with 1300 cGy of γ-irradiation and was transplanted with 4 × 106 BM cells from wild-type C57BL/6 donors. Cell engraftment was monitored by enumeration of the blood cells in regular time intervals. At the end of the experiment, mice were killed and the hematopoietic cell content in the BM was measured by immunophenotypic analysis and CFU-C assay. An untreated group was used as control.

Blood counts

Blood was obtained from treated and untreated mice by cardiac puncture in PBS containing 10mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and 100 U/mL heparin. The enumeration of the blood cells was performed using the SYSMEX SE 9000 hematology analyzer.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test with the level of significance at P less than .05 and expressed as mean ± SEM. For the statistical analysis of the hematopoietic recovery of treated recipients, one-way analysis of variance was used to test for differences among the 3 independent groups: white blood cells, RBCs, and platelet numbers at each time point. A 2-sided significance level of .05 was used.

Results

ALN treatment increases bone mass by inhibiting osteoclastic bone resorption.

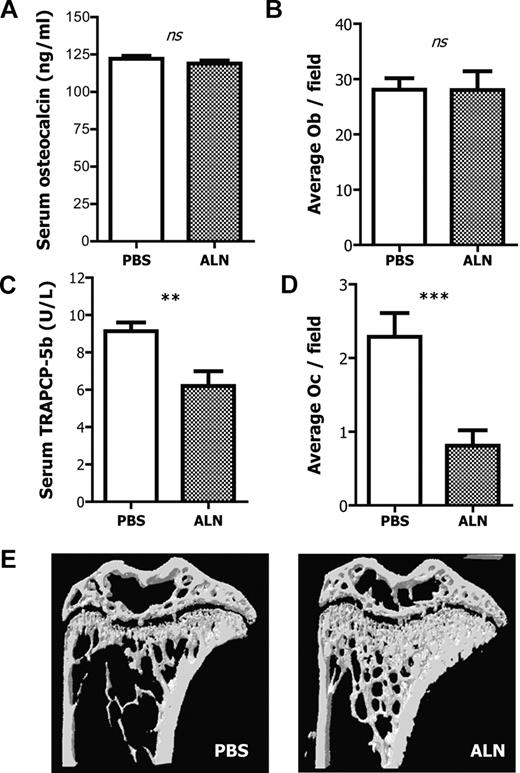

To investigate the effects of the selected dose and duration of ALN treatment on different bone parameters, we assessed serum measurements of bone turnover, cell numbers by histomorphometry, as well as bone mass via micro-CT analysis. There was no effect on either osteocalcin levels, a measure of osteoblast activity, or the number of osteoblasts per field between the PBS and ALN-treated groups indicating that ALN did not have a significant effect on the number and activity of osteoblasts (Figure 1A-B). In contrast, ALN-treated mice exhibited statistically significant decreased levels of TRAPCP-5b compared with control mice (injected with PBS), thus indicating that ALN reduces the number and function of osteoclasts (Figure 1C). This reduction was confirmed by counting osteoclast number by histomorphometric analysis; there were significantly fewer osteoclasts compared with the PBS-treated mice (Figure 1D). The presence of round TRAP+ cells spread throughout the BM cavity was observed in the ALN-treated bone sections (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article); this is characteristic of the osteoclast apoptosis frequently observed after bisphosphonate treatment.32,33

Effects of ALN treatment on bone and bone cells. (A) ALN-treated and untreated mice have comparable levels of blood serum osteocalcin as measured by ELISA. Columns represent mean plus or minus SEM; n = 8. (B) ALN treatment has no effect on the number of osteoblasts per field as measured by histomorphometry. (C) Blood serum TRAPCP-5b concentration is reduced in the ALN-treated mice compared with the untreated controls as measured by ELISA. Columns represent mean ± SEM; n = 8. (D) ALN treatment reduces the number of osteoclasts per field as measured by histomorphometry. (E) Representative three-dimensional reconstruction models of tibias from ALN-treated or untreated mice, indicating that in vivo administration of ALN increases the bone mass and alters the bone microarchitecture. ns indicates not significant.

Effects of ALN treatment on bone and bone cells. (A) ALN-treated and untreated mice have comparable levels of blood serum osteocalcin as measured by ELISA. Columns represent mean plus or minus SEM; n = 8. (B) ALN treatment has no effect on the number of osteoblasts per field as measured by histomorphometry. (C) Blood serum TRAPCP-5b concentration is reduced in the ALN-treated mice compared with the untreated controls as measured by ELISA. Columns represent mean ± SEM; n = 8. (D) ALN treatment reduces the number of osteoclasts per field as measured by histomorphometry. (E) Representative three-dimensional reconstruction models of tibias from ALN-treated or untreated mice, indicating that in vivo administration of ALN increases the bone mass and alters the bone microarchitecture. ns indicates not significant.

To fully evaluate the effects of ALN on bone microarchitecture, tibias were subjected to micro-CT analysis, and the actual values of the bone morphometric parameters are shown in Table 1. Four weeks of ALN treatment produced highly significant changes to the bone morphometric parameters. BV was 97% higher in the ALN-treated mice compared with untreated ones, whereas the percentage of BV/TV was increased by 93%. The bone surface (BS) was also elevated by 78% and the percentage of bone surface, as a ratio of the total volume (BS/TV), was 74% greater. Interestingly, the trabecular thickness was increased by a much lower degree than the rest of the morphometric parameters (10%). Trabecular pattern factor was 124% reduced in the ALN-treated mice, whereas the trabecular number was 85% higher, indicating that the ALN-treated mice have a better-connected network of trabeculae within the BM cavity. The trabecular separation, which represents the “thickness” of the BM cavity, was found to be 42% reduced in the ALN-treated mice compared with the age-matched controls, indicating that the actual space in the BM cavity is ultimately reduced in the ALN-treated mice (Figure 1E). Accordingly, the number of the BM cells per tibia obtained from the ALN-treated mice was 22% reduced compared with the untreated age-matched control animals (56.8 × 106 ± 12.5 × 106 and 68.9 × 106 ± 10.5 × 106, respectively; P < .001).

Trabecular morphologic parameters as defined by micro-CT analysis in tibias of mice treated with ALN for 4 weeks

| . | Untreated . | ALN-treated . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| TV, mm3 | 1.59 ± 0.18 | 1.68 ± 0.10 | .48 |

| BV, mm3 | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 0.48 ± 0.02 | < .001 |

| BV/TV | 10.36 ± 1.55 | 28.54 ± 1.41 | < .001 |

| TS, mm2 | 10.01 ± 0.84 | 10.14 ± 0.21 | .8 |

| BS, mm2 | 14.8 ± 0.39 | 33.68 ± 1.02 | < .001 |

| BS/TV, 1/mm | 9.21 ± 1.72 | 20.04 ± 0.69 | < .001 |

| Tb.Th, mm | 0.046 ± 0.003 | 0.051 ± 0.001 | < .05 |

| Tb.Sp, mm | 0.24 ± 0.043 | 0.16 ± 0.014 | < .05 |

| Tb.N, 1/mm | 2.29 ± 0.47 | 5.65 ± 0.19 | < .001 |

| Tb.Pf, 1/mm | 28.13 ± 0.99 | 6.51 ± 1.6 | < .001 |

| . | Untreated . | ALN-treated . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| TV, mm3 | 1.59 ± 0.18 | 1.68 ± 0.10 | .48 |

| BV, mm3 | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 0.48 ± 0.02 | < .001 |

| BV/TV | 10.36 ± 1.55 | 28.54 ± 1.41 | < .001 |

| TS, mm2 | 10.01 ± 0.84 | 10.14 ± 0.21 | .8 |

| BS, mm2 | 14.8 ± 0.39 | 33.68 ± 1.02 | < .001 |

| BS/TV, 1/mm | 9.21 ± 1.72 | 20.04 ± 0.69 | < .001 |

| Tb.Th, mm | 0.046 ± 0.003 | 0.051 ± 0.001 | < .05 |

| Tb.Sp, mm | 0.24 ± 0.043 | 0.16 ± 0.014 | < .05 |

| Tb.N, 1/mm | 2.29 ± 0.47 | 5.65 ± 0.19 | < .001 |

| Tb.Pf, 1/mm | 28.13 ± 0.99 | 6.51 ± 1.6 | < .001 |

Data are mean ± SEM; n = 4.

TS indicates tissue surface; BS, bone surface; BS/TV, percentage of bone surface; BV/TV, percentage of bone volume; Tb.Th, trabecular thickness; Tb.Sp, trabecular separation; Tb.N, trabecular number; and Tb.Pf, trabecular pattern factor.

Osteoclast impaired mice have reduced number of HSCs with altered cell cycling profile

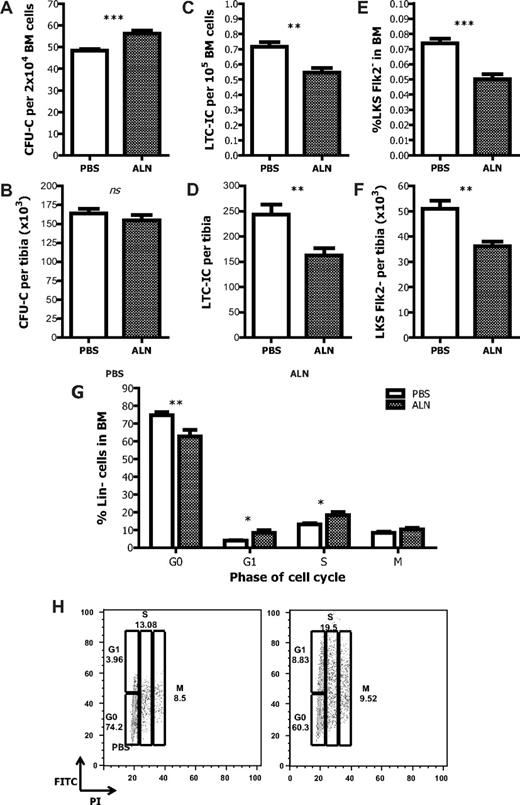

We next sought to investigate the effects of osteoclastic inhibition on hematopoiesis. By assessing the composition of BM cells by the CFU-C assay, we found that the proportion of hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) was increased in ALN-treated mice compared with untreated controls (Figure 2A). Nevertheless, when the actual number of CFU-C per tibia was defined, it was found to be comparable between the 2 groups (Figure 2B). Thus, there is a preferential increase in HPC number at the expense of the other BM cells in the ALN-treated mice. Such an increase cannot be ascribed to a direct effect of ALN because when the latter was added directly to CFU-C cultures no difference in the number of colonies was observed compared with controls (supplemental Figure 2).

Effects of the inhibition of osteoclastic bone resorption on hematopoiesis. (A) ALN-treated mice have increased HPC frequency in the BM as measured by the CFU-C assay. (B) The total number of the HPC per tibia remains unchanged. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 12. The proportion (C) and the actual number (D) of the HSCs in the BM of ALN-treated mice are reduced compared with the untreated age-matched controls as measured by the LTC-IC assay and the immunophenotyping enumeration by FACS analysis (E-F). (G) The proportion of lineage-negative cells found in the different phases of the cell cycle is changed in the ALN-treated animals compared with control; n = 3. (H) Representative graphs from 3 different experiments. *P < .05. **P < .01. ***P < .001. ns indicates not significant.

Effects of the inhibition of osteoclastic bone resorption on hematopoiesis. (A) ALN-treated mice have increased HPC frequency in the BM as measured by the CFU-C assay. (B) The total number of the HPC per tibia remains unchanged. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 12. The proportion (C) and the actual number (D) of the HSCs in the BM of ALN-treated mice are reduced compared with the untreated age-matched controls as measured by the LTC-IC assay and the immunophenotyping enumeration by FACS analysis (E-F). (G) The proportion of lineage-negative cells found in the different phases of the cell cycle is changed in the ALN-treated animals compared with control; n = 3. (H) Representative graphs from 3 different experiments. *P < .05. **P < .01. ***P < .001. ns indicates not significant.

Primitive HSCs were evaluated by measuring LTC-IC assays and by enumerating LKS Flk2− cells in the BM by FACS. The LTC-IC assay showed that ALN-treated mice had a reduction in both the proportion and actual number of primitive HSCs per tibia (Figure 2C-D). Likewise, there was a significant decrease in the relative percentage of LKS Flk2− cells in the osteoclast impaired mice (Figure 2E). The actual number of the LKS Flk2− cells per tibia was also statistically significant reduced (untreated 50 900 ± 12 300 vs ALN-treated 36 100 ± 5200, P < .01; Figure 2F).

To prove that the effect of ALN treatment in the hematopoietic compartment was mediated through its action to reduce osteoclast number, we also blocked osteoclast function by administering calcitonin in mice. A similar reduction in the proportion and the absolute number of both CFU-C and HSCs were observed in the calcitonin-treated mice compared with PBS-treated controls (supplemental Figure 3A-D), suggesting that the effects observed are the result of the impaired osteoclastic bone-resorbing activity and not the result of nonspecific toxicity induced by unbound bisphosphonates.

One of the reasons for the observed differences in the content of progenitors and primitive HSCs could be that, after the ALN treatment, HSCs undergo proliferation and differentiation. Therefore, the cell cycle kinetics of lineage-negative cells obtained from the BM of ALN-treated or untreated mice were defined by FACS analysis. In the ALN-treated mice, the proportion of cells found in G0 was decreased compared with the untreated controls (74.2% vs 60.3%). This was accompanied by an increase in the proportion of cells found in G1 and S phase (3.96% vs 8.83% and 19.5% vs 13.08%, respectively), whereas the proportion of cells found in M phase remained unchanged (Figure 2G-H). Thus, in the osteoclast impaired mice, a higher proportion of HSCs enter the cell cycle compared with the controls.

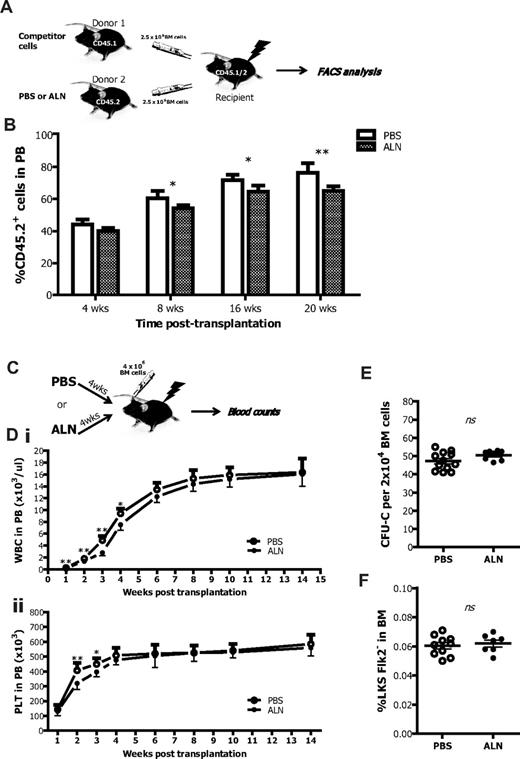

Inhibition of osteoclast activity impairs HSC engraftment in both donor and recipient mice

To assess the effect of osteoclast inhibition on the HSC niche, we performed a series of competitive repopulation assays. Lethally irradiated recipient mice received BM cells from ALN-treated donors and engraftment was evaluated 8, 16, and 20 weeks after transplantation. At all time points, we observed a lower level of engraftment compared with recipient mice receiving BM cells from untreated controls, thus in accord with the decreased HSC numbers in ALN treated mice (Figure 3A). Interestingly, the engraftment 4 weeks after transplantation was comparable with the untreated BM cells possibly resulting from the different cell cycle profile and the increased number of HPCs that may initially compensate for the reduced HSC number (Figure 3B).

Osteoclast impaired mice as donors or recipients in transplantation settings. (A) CD45.2 BM cells from control or ALN-treated mice were mixed with equal amounts of CD45.1 competitor BM cells and transplanted into lethally irradiated CD45.2/CD45.1 recipients. The percentage of CD45.2+ cells was then determined into the PB of recipient mice by FACS analysis at regular time intervals. (B) BM cells from ALN-injected mice had impaired ability to reconstitute in the long-term lethally irradiated recipients as shown by flow cytometry for CD45.2. Columns represent mean ± SEM; n = 6 in each group. *P < .05. **P < .01. (C) Recipient mice that received 4 weekly injections of ALN before γ-irradiation with 13 cGy were reconstituted with 4 × 106 BM cells. An untreated group was used as controls, and the engraftment was monitored by blood enumeration at regular time intervals. (D) ALN-injected mice had reduced numbers of (i) white blood cells and (ii) platelets (PLT) within the first 4 weeks after transplantation. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 8. *P < .05. **P < .01. ns indicates not significant. (E) ALN pretreated recipients fully recover 16 weeks after transplantation because they exhibited comparable frequencies of CFU-C and (F) LKSFlk2− cells in the BM population to the untreated controls. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 8.

Osteoclast impaired mice as donors or recipients in transplantation settings. (A) CD45.2 BM cells from control or ALN-treated mice were mixed with equal amounts of CD45.1 competitor BM cells and transplanted into lethally irradiated CD45.2/CD45.1 recipients. The percentage of CD45.2+ cells was then determined into the PB of recipient mice by FACS analysis at regular time intervals. (B) BM cells from ALN-injected mice had impaired ability to reconstitute in the long-term lethally irradiated recipients as shown by flow cytometry for CD45.2. Columns represent mean ± SEM; n = 6 in each group. *P < .05. **P < .01. (C) Recipient mice that received 4 weekly injections of ALN before γ-irradiation with 13 cGy were reconstituted with 4 × 106 BM cells. An untreated group was used as controls, and the engraftment was monitored by blood enumeration at regular time intervals. (D) ALN-injected mice had reduced numbers of (i) white blood cells and (ii) platelets (PLT) within the first 4 weeks after transplantation. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 8. *P < .05. **P < .01. ns indicates not significant. (E) ALN pretreated recipients fully recover 16 weeks after transplantation because they exhibited comparable frequencies of CFU-C and (F) LKSFlk2− cells in the BM population to the untreated controls. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 8.

The effect of reduced osteoclast activity was also investigated on the hematopoietic niche of donor origin. Lethally irradiated recipient mice, previously treated with ALN or untreated, were transplanted with BM cells from untreated donor mice (Figure 3C). ALN-treated recipients showed a reduced number of white blood cells 2, 3, and 4 weeks after transplantation and reduced number of platelets 2 and 3 weeks after transplantation (Figure 3D). This effect was short-term because it was reversed at the sixth week after transplantation, and thereafter ALN-treated and untreated recipients had similar blood counts. Accordingly, when the mice were killed 16 weeks after transplantation, the proportion of HPCs, measured by the CFU-C assay (Figure 3E), as well as the frequency of the LKSFlk2− cells (Figure 3F), were comparable between the 2 different groups.

Inhibition of the osteoclastic function augments the effects of PTH on the bone morphometric parameters

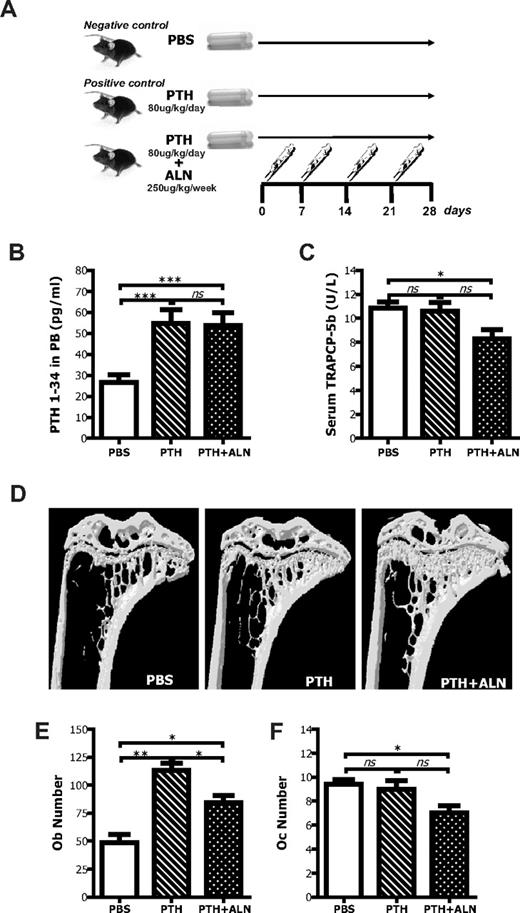

To better characterize the significance of the osteoclastic inhibition on the HSC niche, we investigated its effect on the PTH-mediated HSC-promoting activity.8 C57BL/6 mice were treated with PTH alone or PTH and ALN following the regimen shown in Figure 4A. To ensure the delivery of PTH from Alzet osmotic pumps, serum blood was assayed for the levels of circulating PTH by immunoradiometric assay. High amounts of PTH were detected only in mice implanted with PTH-loaded pumps, whereas in those implanted with pumps loaded with PBS alone basal levels were detected (Figure 4B). Any experimental mice that did not have elevated levels of PTH in the serum were excluded from further analysis.

Effects of coadministration of PTH and ALN on bone and bone cells. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental procedure to analyze the effects of PTH + ALN coadministration on the HSC niche. (B) Experimental mice that were continuously treated with PTH (1-34) with the use of Alzet osmotic pumps had increased levels of PTH in the serum blood as determined by immunoradiometric assay. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 8. ***P < .001. (C) PTH + ALN-treated mice, but not PTH-treated mice, had reduced concentration of TRAPCP-5b in the PB as defined by ELISA. Columns represent mean plus or minus SEM; n = 8. *P < .05. (D) Tibias from PTH-, PTH + ALN-treated, or untreated mice were subjected to micro-CT scanning, reconstructed with the use of Nrecon and CTAn software programs, and visualized by the use of CTVol program (SkyScan). Representative transaxial views of tibias indicating that in vivo coadministration of PTH and ALN produces greater changes in the bone morphometric parameters than PTH alone. (E) Osteoblast number (Ob.N) and (F) osteoclast number (Oc.N) were defined by histomorphometry in methyl methacrylate-embedded tibial sections stained with toluidine blue. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 6. *P < .05. **P < .01. ns indicates not significant.

Effects of coadministration of PTH and ALN on bone and bone cells. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental procedure to analyze the effects of PTH + ALN coadministration on the HSC niche. (B) Experimental mice that were continuously treated with PTH (1-34) with the use of Alzet osmotic pumps had increased levels of PTH in the serum blood as determined by immunoradiometric assay. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 8. ***P < .001. (C) PTH + ALN-treated mice, but not PTH-treated mice, had reduced concentration of TRAPCP-5b in the PB as defined by ELISA. Columns represent mean plus or minus SEM; n = 8. *P < .05. (D) Tibias from PTH-, PTH + ALN-treated, or untreated mice were subjected to micro-CT scanning, reconstructed with the use of Nrecon and CTAn software programs, and visualized by the use of CTVol program (SkyScan). Representative transaxial views of tibias indicating that in vivo coadministration of PTH and ALN produces greater changes in the bone morphometric parameters than PTH alone. (E) Osteoblast number (Ob.N) and (F) osteoclast number (Oc.N) were defined by histomorphometry in methyl methacrylate-embedded tibial sections stained with toluidine blue. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 6. *P < .05. **P < .01. ns indicates not significant.

As an assessment of osteoclast activity, the concentration of TRAPCP-5b was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Mice from the PTH + ALN-treated group had a reduced concentration of TRAP in serum blood compared with the ones that received PBS (P < .05). No difference was observed in the PTH-treated group (P = .79), indicating that PTH did not significantly alter the number and function of osteoclasts under these experimental conditions, as opposed to ALN (Figure 4C; supplemental Figure 4). The actual values of the bone morphometric parameters are shown in Table 2 (reconstructed images in Figure 4D). Both PTH- and PTH + ALN-treated mice exhibited statistically significant changes in all the different bone morphometric parameters, compared with PBS-treated age-matched controls, yet the changes in the mice that received PTH + ALN were greater. Indeed, PTH + ALN-treated animals exhibited a reduction in the size of the BM cavity compared with the control littermates; however, this was not true for the PTH-treated mice. Similarly, the number of the BM cells obtained per tibias from the PTH + ALN-treated mice was significantly reduced (30%) compared with the untreated age-matched control animals (47.7 × 106 ± 7.8 × 106 and 65.2 × 106 ± 7.8 × 106, respectively, P < .001), whereas the 10% difference observed in the number of BM cells from PTH-treated animals was not statistically significant (58.8 × 106 ± 5.9 × 106). As expected, there was a significant increase in osteoblast numbers in response to PTH that was diminished by the coadministration of ALN (Figure 4E). Interestingly, there were still significantly more osteoblast in the PTH + ALN compared with the PBS group, yet they have equivalent numbers of LKS Flk2− cells in the BM, indicating that the increase in osteoblast numbers alone was insufficient to induce HSC to remain quiescent in their niches.

Trabecular morphologic parameters in the tibia of untreated, PTH-treated, and PTH + ALN-treated mice measured by micro-CT analysis

| . | Untreated . | PTH-treated . | P . | PTH + ALN-treated . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TV, mm3 | 1.86 ± 0.13 | 2.44 ± 0.20 | < .001 | 2.44 ± 0.13 | < .001 |

| BV, mm3 | 0.20 ± 0.026 | 0.39 ± 0.082 | < .001 | 0.71 ± 0.105 | < .001 |

| BV/TV | 10.82 ± 0.85 | 15.47 ± 2.05 | < .001 | 29.21 ± 3.30 | < .001 |

| TS, mm2 | 12.17 ± 0.88 | 15.19 ± 0.86 | < .001 | 14.97 ± 1.26 | < .001 |

| BS, mm2 | 16.71 ± 1.51 | 33.53 ± 3.33 | < .001 | 49.20 ± 8.23 | < .001 |

| BS/TV, 1/mm | 8.99 ± 0.47 | 13.67 ± 1.75 | < .001 | 20.11 ± 2.64 | < .001 |

| Tb.Th, mm | 0.049 ± 0.003 | 0.05 ± 0.004 | .66 | 0.053 ± 0.003 | < .05 |

| Tb.Sp, mm | 0.26 ± 0.013 | 0.22 ± 0.027 | < .001 | 0.19 ± 0.034 | < .001 |

| Tb.N, 1/mm | 2.21 ± 0.26 | 3.30 ± 0.42 | < .001 | 5.51 ± 0.68 | < .001 |

| Tb.Pf, 1/mm | 20.03 ± 2.28 | 12.4 ± 5.45 | < .01 | 12.1 ± 5.23 | < .001 |

| . | Untreated . | PTH-treated . | P . | PTH + ALN-treated . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TV, mm3 | 1.86 ± 0.13 | 2.44 ± 0.20 | < .001 | 2.44 ± 0.13 | < .001 |

| BV, mm3 | 0.20 ± 0.026 | 0.39 ± 0.082 | < .001 | 0.71 ± 0.105 | < .001 |

| BV/TV | 10.82 ± 0.85 | 15.47 ± 2.05 | < .001 | 29.21 ± 3.30 | < .001 |

| TS, mm2 | 12.17 ± 0.88 | 15.19 ± 0.86 | < .001 | 14.97 ± 1.26 | < .001 |

| BS, mm2 | 16.71 ± 1.51 | 33.53 ± 3.33 | < .001 | 49.20 ± 8.23 | < .001 |

| BS/TV, 1/mm | 8.99 ± 0.47 | 13.67 ± 1.75 | < .001 | 20.11 ± 2.64 | < .001 |

| Tb.Th, mm | 0.049 ± 0.003 | 0.05 ± 0.004 | .66 | 0.053 ± 0.003 | < .05 |

| Tb.Sp, mm | 0.26 ± 0.013 | 0.22 ± 0.027 | < .001 | 0.19 ± 0.034 | < .001 |

| Tb.N, 1/mm | 2.21 ± 0.26 | 3.30 ± 0.42 | < .001 | 5.51 ± 0.68 | < .001 |

| Tb.Pf, 1/mm | 20.03 ± 2.28 | 12.4 ± 5.45 | < .01 | 12.1 ± 5.23 | < .001 |

Data are mean ± SEM; n = 4.

TS indicates tissue surface; BS, bone surface; BS/TV, percentage of bone surface; BV/TV, percentage of bone volume; Tb.Th, trabecular thickness; Tb.Sp, trabecular separation; Tb.N, trabecular number; and Tb.Pf, trabecular pattern factor.

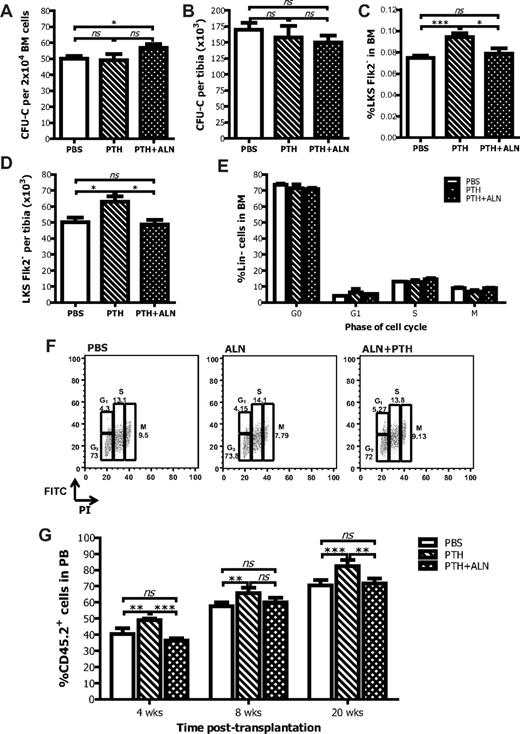

Inhibition of the osteoclastic function abolishes the beneficial effects of PTH on the HSC niche

BM cells from PTH- or PTH + ALN-treated and vehicle control treated mice were evaluated for the frequency of hematopoietic progenitors by enumerating the CFU-C. After coadministration of PTH + ALN, a statistically significant increase in the frequency of CFU-C was observed compared with PBS-treated control mice, whereas no change was documented in the PTH-treated group (Figure 5A), although when the total number of CFU-C per tibia was calculated, there was no statistical difference between the groups (Figure 5B). These results suggest that, although there is a loss of hematopoietic space in PTH + ALN-treated mice and hence in the absolute number of total cells/tibia, hematopoietic progenitors are preserved. PTH administration increased both the absolute number and the frequency of LKS Flk2− cells (Figure 5C-D), in agreement with previously published results.8 Interestingly, when ALN was coadministered with PTH, the percentage and absolute number of LKS Flk2− cells in the BM were comparable with the PBS-treated control group. Furthermore, in the spleen, the percentage of LKS Flk2− cells was elevated with PTH but not with PTH + ALN treatment (supplemental Figure 5). Thus, ALN coadministration abolished the HSC expansion in the niche, indicating that osteoclast function is necessary for this effect. Unlike ALN treatment alone, neither PTH nor PTH + ALN treatment resulted in an alteration of the cell cycle characteristics of the lineage-negative cells (Figure 5E-F). This finding is in correlation with the CFU-C data (Figure 5A-B).

Effects of coadministration of PTH and ALN on hematopoiesis. PTH + ALN-treated mice have increased HPC frequency in the BM (A) but unchanged absolute number per tibia (B) as measured by the CFU-C assay. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 8. *P < .05. PTH-treated mice have increased proportion (C) and absolute numbers (D) of LKSFlk2− cells in the BM, whereas PTH + ALN-treated mice have a comparable number of HSCs with the untreated age-matched controls as defined by FACS analysis. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 8. ***P < .001. (E) The cell-cycle kinetics of the lineage-negative cells are comparable between untreated, PTH-treated, and PTH + ALN treated mice. (F) Representative graphs of the cell cycle analysis by FACS. (G) BM cells from PTH-treated mice have increased ability to reconstitute irradiated recipients as shown by FACS analysis for CD45.2 at 4, 8, and 20 weeks after transplantation; after coadministration of ALN, this effect is abolished. Columns represent mean ± SEM; n = 6 in each group. **P < .01. ***P < .001. ns indicates not significant.

Effects of coadministration of PTH and ALN on hematopoiesis. PTH + ALN-treated mice have increased HPC frequency in the BM (A) but unchanged absolute number per tibia (B) as measured by the CFU-C assay. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 8. *P < .05. PTH-treated mice have increased proportion (C) and absolute numbers (D) of LKSFlk2− cells in the BM, whereas PTH + ALN-treated mice have a comparable number of HSCs with the untreated age-matched controls as defined by FACS analysis. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 8. ***P < .001. (E) The cell-cycle kinetics of the lineage-negative cells are comparable between untreated, PTH-treated, and PTH + ALN treated mice. (F) Representative graphs of the cell cycle analysis by FACS. (G) BM cells from PTH-treated mice have increased ability to reconstitute irradiated recipients as shown by FACS analysis for CD45.2 at 4, 8, and 20 weeks after transplantation; after coadministration of ALN, this effect is abolished. Columns represent mean ± SEM; n = 6 in each group. **P < .01. ***P < .001. ns indicates not significant.

We then assessed the ability of BM cells extracted from donor mice untreated or treated for 4 weeks with PTH or PTH + ALN to repopulate myeloablated recipients. A competitive repopulation experiment was performed as described before, where the use of the CD45.1/CD45.2 system, enabled us to identify the progeny of the HSCs of interest by performing FACS analysis for the CD45.2+ cells in the PB of recipient mice. The percentage of CD45.2+ cells was higher in the peripheral blood of recipient mice that had received BM cells from PTH-treated mice compared with the percentage of CD45.2+ cells detected in the peripheral blood of vehicle control treated mice, indicating that there was an increment in primitive HSC number after PTH administration. However, the percentage of CD45.2+ cells in the peripheral blood of recipients that had received BM cells from donor mice treated with PTH + ALN was comparable with the PBS-treated control group. Therefore, when ALN was administered in combination with PTH in donor mice, the enhanced ability of BM cells to reconstitute the irradiated recipients was abolished (Figure 5G). This result is consistent with the previous finding that PTH + ALN-treated mice had the same number of HSCs in the BM as PBS-treated control mice (Figure 5C-D).

Discussion

Recently, the HSC niche has been proposed as a new target for innovative therapeutic approaches. PTH was recently used in a phase I clinical trial to mobilize HSCs in patients with encouraging results.34 In approximately 47% of patients who had previously failed one HSC mobilization attempt, PTH treatment mobilized sufficient HSCs to proceed safely to autologous HSC transplantation.35 Furthermore, prostaglandin E2 and its downstream Gαs pathway have been shown to affect HSC engraftment and are now investigated in clinical trials.36 Understanding the mechanisms involved in regulating the hematopoietic niche would therefore prompt the development of a novel approach to facilitate HSC transplantation.

We tested the hypothesis that osteoclasts may participate in the regulation of the HSC niche. For this purpose, we manipulated osteoclast number/function in vivo using bisphosphonates, well-characterized antiresorptive agents that are used in the treatment of bone disorders because of their apoptotic activity on osteoclasts. Mice treated with ALN showed increased BV specifically as a result of the inhibition of osteoclastic bone resorption (Figure 1). In osteoclast impaired mice, the frequency of HPCs in the BM was increased, whereas their absolute number remained unchanged (Figure 2A-B). Calcitonin treatment was used as another method of inhibiting osteoclast activity and showed equivalent effects to ALN for the CFU-C and LTC-IC assays (supplemental Figure 3). However, it is possible that inhibiting osteoclasts with ALN may have an indirect effect on HSC activity directly should these cells come into contact with any free compound. Because osteoclasts are implicated in the egress of the HSCs/progenitor cells from the BM,21 we cannot exclude the possibility that, after ALN, progenitor cells accumulate in the BM as a result of impaired mobilization.21 However, ALN-treated mice exhibited a reduction in both the proportion and absolute number of HSCs in BM of ALN-treated mice (Figure 2C-D), and similarly the long-term engraftment of BM cells from donor ALN-treated mice was inferior to that of the controls as tested in a competitive repopulation assay (Figure 3A-B). Furthermore, we observed a higher proportion of LKS cells in the S/M phase of the cell cycle (Figure 2E), thus suggesting that a proportion of HSCs enter the cell cycle and differentiate, thereby increasing the HPC fraction. A preferential expansion of the HPCs has been recently observed in mice treated with prostaglandin E2, which alters the BM composition acting on both the osteoblasts and osteoclasts,37 lending support to our hypothesis that perturbation of bone remodeling balance leads to changes in the HSC composition. It should also be noted that bisphosphonates have been shown to have both direct and indirect effects on osteoblast and osteocyte function.38,39 These effects are the result of the prevention of osteoblast apoptosis and the perturbation of osteoblast/osteoclast coupling mechanisms,15 respectively. Consequently, the lack of new osteoblasts on the endosteal surfaces may also contribute to the reduction in HSC numbers.

One of the fundamental experiments corroborating the notion that cells of the osteoblast lineage regulate the size of the HSC niche8,9,40 was based on the demonstration that the administration of PTH in mice increased the number of HSCs by expanding the number of osteoblasts. However, PTH is able to promote both osteoblast and osteoclast function when administered continuously.41,42 In our model, PTH was administered continuously with an Alzet osmotic pump, resulting in a net gain in bone mass (Table 2). This is in agreement with previous studies in estrogen-deficient rats where continuous administration of PTH using Alzet osmotic minipumps augmented net bone formation.43,44 Interestingly, mice with c-fos ablation, which are osteopetrotic resulting from impaired osteoclastic bone resorption, lack an anabolic response to PTH.45 Similarly, mice treated with osteoprotegerin, which inhibits osteoclast differentiation, fail to exhibit PTH anabolic effects,46 thus demonstrating that cells of the osteoclastic lineage are crucial mediators of the PTH anabolic action. Therefore, we hypothesized that cells of osteoclastic lineage may similarly be the intermediate targets for the PTH-promoting effect on the HSC niche. When we administered PTH together with ALN, we observed that the beneficial effect of PTH on the HSC niche was abolished. PTH + ALN-treated mice had comparable numbers of HSC in the BM as PBS-treated controls (Figure 5B). Accordingly, ALN administration abolished the ability of PTH to confer superior hematopoietic reconstitution ability to donor BM (Figure 5D). When the actual number of osteoblasts and osteoclasts in the BM of the different groups was counted, it was observed that PTH + ALN-treated mice had a decreased number of osteoclasts accompanied by an increase in osteoblasts, whereas PTH-treated mice had unchanged osteoclast numbers and a greater number of osteoblasts (Figure 4; supplemental Figure 4). The possibility that ALN reduced osteoblast activity and/or number directly was considered; however, ALN alone did not affect osteoblast numbers or serum osteocalcin levels (Figure 1A-B). These results suggest that the inhibition of the osteoclast-mediated bone resorption impairs the production of sufficient numbers of niche-type osteoblasts. Alternatively, the depletion of osteoclast-derived factors may lead to a reduction in the formation of niche-type osteoblasts and/or their ability to support HSCs.

Several lines of evidence suggest that some subsets of osteoblasts are important in the HSC niche whereas others are not.14,47 Osteoblastic cells are a heterogeneous population derived from multipotent mesenchymal progenitors, and the specific role of each subset in the niche remains to be assigned. Osteoblast differentiation/maturation is intimately linked to osteoclast activity and the process of bone remodeling. Osteoblasts secrete factors, such as RANKL48 and OPG,49 which regulate the maturation of pre-osteoclasts and, in turn, factors released from the eroded bone matrix or produced by osteoclasts themselves (bone morphogenetic proteins, insulin growth factor, transforming growth factor-β) are required for the recruitment and the differentiation of osteoprogenitor cells and thus the formation of the niche.

In this study, we demonstrated that, when osteoclastic differentiation is inhibited, the effects on the HSCs are detrimental, and this may be related to an effect on the osteoblasts lining the HSC niche. Osteoclasts constantly change the physical conformation of the BM cavity; therefore, the inhibition of their function may lead to the reduction of the available niche space. There may be a threshold for the minimum required BM cavity space to maintain HSC numbers that, once exceeded, leads to reduction in the number of HSCs. Such a phenomenon is observed in extreme pathologic conditions, such as in osteopetrotic mice, in which the severe reduction of BM space results in establishment of extramedullary hematopoiesis.50 Furthermore, osteoclastic bone resorption retracts “old” osteoblasts from the remodeling endosteal surface and recruits “new” active matrix producing osteoblasts to the eroded bone surface. Thus, inhibition of osteoclast function reduces the rate of osteoblast turnover and may consequently reduce the formation of niche-osteoblasts.

Our findings indicate an important role for osteoclasts in the hematopoietic niche and suggest that their manipulation can be exploited to selectively augment the number/function of niche-type osteoblasts and expedite hematopoietic recovery after HSC transplantation.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by Leukemia & Lymphoma Research.

Authorship

Contribution: S.L. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; A.E. performed research and edited the paper; F.F. analyzed data and edited the paper; F.D. designed research and edited the paper; and N.J.H. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Nicole J. Horwood, Kennedy Institute of Rheumatology, 65 Aspenlea Rd, Charing Cross Campus, Imperial College, London W6 8LH, United Kingdom; e-mail: n.horwood@imperial.ac.uk.