Abstract

Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC), which is largely mediated by natural killer (NK) cells, is thought to play an important role in the efficacy of rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (mAb) used to treat patients with B-cell lymphomas. CD137 is a costimulatory molecule expressed on a variety of immune cells after activation, including NK cells. In the present study, we show that an anti-CD137 agonistic mAb enhances the antilymphoma activity of rituximab by enhancing ADCC. Human NK cells up-regulate CD137 after encountering rituximab-coated tumor B cells, and subsequent stimulation of these NK cells with anti-CD137 mAb enhances rituximab-dependent cytotoxicity against the lymphoma cells. In a syngeneic murine lymphoma model and in a xenotransplanted human lymphoma model, sequential administration of anti-CD20 mAb followed by anti-CD137 mAb had potent antilymphoma activity in vivo. These results support a novel, sequential antibody approach against B-cell malignancies by targeting first the tumor and then the host immune system.

Introduction

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have revolutionized the treatment of cancer. The first approved mAb for this purpose, rituximab, a murine-human chimeric immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) antibody against CD20, has become a standard treatment for patients with B-cell lymphomas.

Despite tumor response rates to rituximab of up to 90% and decreased risk of death by as much as 36%, the majority of patients with advanced lymphoma still die of their disease, including 19 000 patients in the United States in 2009 alone.1-4 Enhancing the efficacy of rituximab represents an opportunity to improve patient outcome. We have developed a strategy to enhance the antitumor activity of rituximab by augmenting antibody-induced cell killing.

Several mechanisms of rituximab's antitumor action have been proposed, including direct induction of apoptosis, complement-dependent cytotoxicity, antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC), and, possibly, induction of an adaptive immune response (a “vaccinal” effect).5 Among these mechanisms, ADCC is believed to be of importance, particularly to the initial antitumor response. In vitro studies have shown that rituximab can induce ADCC of human lymphoma cell lines.6 In murine xenotransplant lymphoma models, a role for ADCC in rituximab's efficacy was confirmed in studies using FcR-γ-chain–deficient mice,7 as well as a neutralizing antibody against murine FcγR.8 Further murine studies using CD20 mAbs have confirmed that monocyte-mediated ADCC is the primary, if not exclusive, mechanism through which normal and malignant B cells are depleted in vivo.9-13 Finally, clinical results have shown that patients harboring an FcγRIIIA polymorphism with higher affinity for IgG1 have better responses to rituximab, further supporting the hypothesis that ADCC is an important in vivo mechanism of rituximab action in patients with lymphoma.14,15 Natural killer (NK) cells are known to be important effector cells mediating ADCC. Binding of the NK-cell Fc receptor (FcγRIII, CD16) to the constant region of an antibody induces NK-cell activation. On activation, NK cells release cytotoxic granules, promoting tumor cell killing, and up-regulate the expression of several activation markers, including CD137.16 In this study, we hypothesized that rituximab-induced ADCC could be specifically increased by using an anti-CD137 agonistic mAb to enhance NK-cell function.

CD137 (4-1BB) is a surface glycoprotein that belongs to the tumor-necrosis factor receptor superfamily.17 CD137 is an inducible costimulatory molecule expressed on a variety of immune cells, including activated CD4 and CD8 T cells, NK cells, monocytes, and dendritic cells.18,19 On T cells specifically, CD137 functions as a costimulatory receptor induced on T-cell receptor stimulation. In this context, ligation of CD137 leads to increased T-cell proliferation, cytokine production, functional maturation, and prolonged CD8 T-cell survival.18,20 Consistent with the costimulatory function of CD137 on T cells, agonistic mAbs against this receptor have been shown to provoke powerful tumor-specific T-cell responses capable of eradicating tumor cells in a variety of murine tumor models, including breast, sarcoma, mastocytoma, glioma, colon carcinoma, and myeloma.20-22 Based on these preclinical results, an agonistic anti-CD137 mAb has now entered clinical trials for solid tumors. More recently, we have shown in a murine model that anti-CD137 agonistic mAb also had potent antilymphoma activity, requiring both CD8 T cells and NK cells.23

Despite extensive studies of its effect on T cells, the role of CD137 stimulation on the innate immune system is less well characterized. Recently, CD137 was shown to be up-regulated on human NK cells after Fc-receptor triggering.16 Further, CD137 stimulation has been shown to enhance NK-cell function in mice,24,25 including a recent report demonstrating increased antitumor activity of NK cells after costimulation by γ-δ T cells, which was dependent on CD137 receptor/ligand interactions.26 We hypothesized that because Fc-receptor triggering results in up-regulation of CD137 expression on NK cells, stimulation via CD137 could enhance NK-cell killing by ADCC and thereby augment the efficacy of rituximab. We first tested this hypothesis in vitro using lymphoma cell lines and then confirmed our findings in vivo in both a syngeneic, immunocompetent mouse model and a human xenotransplant model of lymphoma. We found that human NK cells up-regulated their expression of CD137 when exposed to rituximab-coated, autologous lymphoma cells.

Methods

Cell lines and mice

Human CD20+ B-cell lines, including Raji and Ramos and a CD20− B-cell line, OCI-Ly19, were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). DHL-4– and luciferase-labeled Raji cells transduced with a Luc-2A-eGFP (luciferase-2A-enhanced green fluorescent protein)–containing lentivirus were generated previously at Stanford University (Stanford, CA).27 Cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (HyClone Laboratories), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (both from Invitrogen). The murine CD20+ B-cell line BL3750, a C57BL/6-cell lymphoma, was developed in a cMyc transgenic mouse.12 BL3750 was cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 50μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were grown in suspension culture at 37°C in 5% CO2. BL3750, Raji, Ramos, DHL4, and OCI-Ly19 lymphoma cell lines are negative for CD137-receptor expression. BL3750 and DHL4 are negative for CD137-ligand expression. Raji, Ramos, and OCI-Ly19 express similar, though minimal, levels of CD137 ligand with specific mean fluorescence indices (MFIs; tumor MFI/isotype MFI) of 2.1, 2.2, and 2.7, respectively.

Eight- to 10-week-old female C57BL/6 and severe combined immune deficient (SCID) mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories and Harlan Laboratories, respectively, and were housed at the laboratory animal facility at the Stanford University Medical Center. All experiments were approved by the Stanford Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care and conducted in accordance with Stanford University Animal Facility and National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Therapeutic antibodies

Anti–mouse CD137 (4-1BB) mAb (rat IgG2a, clone 2A28 ), with a half-life of 7 days, was produced from ascites in SCID mice as described previously.23,29 Sterile mouse anti–mouse CD20 mAb (MB20-11, mouse IgG2c) was produced in vitro.12 IgG from rat serum was used as a control antibody (Sigma-Aldrich). Human anti–human CD137 mAb (BMS-663513, human IgG4, which does not block the CD137 ligand) was provided by Bristol-Meyer Squibb. Rituximab (murine-human chimeric anti-CD20 IgG1) and trastuzumab (humanized anti–human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 IgG1) were obtained from Genentech.

CD137 expression on NK cells from patient samples and healthy individuals

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from patients with follicular lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, marginal zone lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and CD20+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and from healthy individuals by density gradient separation using Ficoll-Paque Plus (Amersham Biosciences). Informed consent was received from patients in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and study approval by Stanford University's Administrative Panels on Human Subjects. The percentage of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) for all patient samples was enumerated from clinical laboratory records. Patient PBMC samples were incubated in vitro with no antibody, trastuzumab (10 μg/mL), or rituximab (10 μg/mL) for 24 hours before staining with mAbs and subsequent analysis by flow cytometry for CD137 expression. PBMCs isolated from healthy individuals or purified NK cells isolated by negative magnetic cell sorting using NK-cell–isolation beads (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer's instructions were cultured in complete medium for 24 hours with a B-cell line in the presence or absence of rituximab (10 μg/mL) or trastuzumab (10 μg/mL). Assessment of CD137 expression on NK cells from healthy individuals was performed in triplicate in 3 independent experiments.

In vitro NK functional assays

CD107a mobilization was assayed to evaluate NK-cell degranulation.30 Purified NK cells isolated by negative magnetic cell sorting using NK-cell–isolation beads (Miltenyi Biotec) were cultured alone, with lymphoma cell lines (Raji, Ramos, and DHL-4) at a ratio of 1:1, with rituximab (10 μg/mL), and/or with anti-CD137 agonistic mAb (10 μg/mL) for 24 hours with GolgiStop (BD Biosciences) to prevent degradation of reinternalized CD107a proteins. After 24 hours, cells were washed 3 times and mAb staining was carried out for analysis by flow cytometry. Murine NK cells purified by negative magnetic cell sorting (Miltenyi Biotec) were evaluated for CD137 expression after culture with murine anti–murine anti-CD20 mAb.

To evaluate NK-cell cytotoxicity for lymphoma cell lines, chromium release was performed as follows31 : healthy PBMCs were cultured for 24 hours together with rituximab (10 μg/mL) and irradiated (5000 rads) lymphoma tumor cells (Raji, Ramos, or DHL-4) at a ratio of 1:1. After 24 hours, NK cells were isolated from these cultures by negative magnetic cell sorting using NK-cell–isolation beads (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer's instructions. NK cells were assessed for purity ( > 90% purity as defined by CD3−CD56+ flow cytometry) and CD137 expression ( > 40% for preactivated NK cells) before chromium release assay. Target cells were labeled with 150 μCi of 51Cr per 1 × 106 cells for 2 hours. Percent lysis was determined after 4-hour culture of nonpreactivated or preactivated purified NK cells at variable effector-to-target cell ratios of 12.5:1, 25:1, 50:1, and 100:1 with 51Cr-labeled lymphoma cells in medium alone, with anti-CD137 mAb (BMS-663513, 10 μg/mL) alone, rituximab (10 μg/mL) alone, or rituximab plus anti-CD137 mAbs (both at 10 μg/mL).

Cells were cultured for interferon-γ assessment under conditions similar to those detailed above for the assessment of cytotoxicity. Supernatant was analyzed for interferon-γ using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method (human interferon-γ BD OptEIA ELISA Set and BD OptEIA Reagent Set B; BD Pharmingen). ELISA plates were read on a microplate reader and analyzed using SoftMax software Version 5 (Molecular Devices). Results were reported in picograms per milliliter. In vitro assays, CD107a mobilization, interferon-γ, and chromium release were performed with 3 independent samples.

Tumor transplantation and antibody therapy

BL3750 lymphoma cells were implanted into 8- to 10-week-old female C57BL/6 mice at a dose of 5 × 106 cells in 50 μL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) by the subcutaneous route on the abdomen. Monoclonal antibodies were administered by intraperitoneal injection. Anti-CD20 mAb was given intraperitoneally on day 3 at 250 μg per injection, and anti-CD137 mAb was given intraperitoneally on day 4 at 150 μg per injection. Groups of 10 mice received IgG alone on day 3, anti-CD20 mAb alone on day 3, anti-CD137 mAb alone on day 4, or both anti-CD20 mAb on day 3 and anti-CD137 mAb on day 4. To determine activity against well-established tumors, the identical treatment groups and sequence of antibodies were initiated on day 8 (IgG alone on day 8, anti-CD20 mAb alone on day 8, anti-CD137 mAb alone on day 9, or both anti-CD20 mAb on day 8 and anti-CD137 mAb on day 9). To optimize the sequence of antibody treatment, the anti-CD20 and anti-CD137 mAbs were given simultaneously on day 3 and directly compared with anti-CD20 mAb on day 3 and anti-CD137 mAb on day 4 in groups of 10 mice. Tumor growth was measured by caliper twice a week, and expressed as the product of length by width in square centimeters. Mice were killed when tumor size reached 4 cm2 or when tumor sites ulcerated. All in vivo models were piloted with 5 mice per group and repeated with 10 mice per group.

Detection of CD137-expressing cells in vivo

Blood was collected from the tail vein, anticoagulated with 2mM EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) in PBS, diluted 1:1 with 2% dextran T500 (Pharmacosmos) in PBS, and incubated at 37°C for 45 minutes to precipitate red cells. Leukocyte-containing supernatant was removed and centrifuged, and the remaining red cells were lysed with ACK (ammonium chloride-potassium chloride) lysis buffer (Quality Biological). Subcutaneous tumors from 3 mice per treatment group were resected 7 days after inoculation and mechanically digested into a single cell suspension. Cells were stained with mAbs to evaluate CD137 expression on NK cells, macrophages, and CD4 and CD8 T cells by flow cytometry.

Depletion of CD8 T cells, NK cells, and macrophages

Anti-CD8 mAb, anti-Asialo GM1 mAb (Wako Chemicals), and liposomal clodronate (kindly provided by the Weissman laboratory at Stanford University) were used to deplete CD8 T-cell, NK-cell, and macrophage activity in vivo, respectively. Ascitic fluid was harvested from SCID mice bearing hybridoma 2.43 producing anti-CD8 (Rat IgG2b) mAb. The ascites were diluted in sterile PBS. Depleting anti-CD8 mAb and anti-Asialo GM1 mAb were injected intraperitoneally on day −1, day 0 of tumor inoculation, and every 5 days thereafter for 4 weeks at a dose of 500 μg per injection of anti-CD8 mAb and 50 μL per injection of anti-Asialo GM1 mAb. Liposomal clodronate was injected retro-orbitally on day −2 at a dose of 200 μL, on day 0 of tumor inoculation, followed by every 4 days thereafter for 4 weeks per injection at a dose of 100 μL. The depletion conditions were validated by flow cytometry of blood showing more than 95% depletion of CD8 T cells, 93% depletion of NK cells, and 91% depletion of macrophages, respectively.

Disseminated lymphoma xenotransplant model and antibody therapy

Luciferase-labeled Raji cells (3 × 106) were injected intravenously into the retro-orbital sinus of sublethally irradiated (200 rads) 8- to 10-week-old SCID mice. Mice were imaged for luciferase-positive cells every 10 days to determine lymphoma engraftment and treatment response. Rituximab was given intraperitoneally on day 3 at 200 μg per injection, and anti-CD137 mAb was given intraperitoneally on day 4 at 150 μg per injection. Groups of 5 mice received IgG alone on day 3, rituximab alone on day 3, anti-CD137 mAb alone on day 4, or both rituximab on day 3 and anti-CD137 mAb on day 4. Antibody treatment was continued weekly for 4 weeks and then stopped, and mice were followed for survival analysis. The model was piloted and repeated once with 5 mice per group.

Luciferase imaging and analysis

Mice were imaged at the Stanford Center for Innovation in In-Vivo Imaging. They were anesthetized and given an intraperitoneal injection of firefly D-luciferin (Biosynth) at a dose of 375 mg/kg mouse body weight.32 Luciferase imaging of mice was then performed using the Xenogen In Vivo Imaging System (IVIS) Spectrum (Caliper LifeSciences) with a 1- to 60-second exposure time, medium binning, and a 16 f/stop. Multiple images were taken until the luciferase signal intensity reached a plateau, and image parameters were kept identical for the duration of the experiments. Luciferase image analysis was performed using Living Image 3.0 (Caliper LifeSciences). Luciferase light units were quantified in average radiance per region of interest (photons emitted/whole mouse/second).

Antibodies for flow cytometry

The following mAbs to human antigens were used for staining of human PBMCs: CD16 fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), CD107a FITC, CD137 ligand phycoerythrin (PE), CD56 PE, CD20 PE, CD62L PE-Cy5, CD3 peridinin chlorophyll A protein (PerCP), CD137 allophycocyanin (APC), and CD69 APC-H7 (all from BD Biosciences). The following mAbs to mouse antigens were used: CD8 FITC (BD Biosciences), CD4 FITC (BD Biosciences), CD137 ligand PE (eBioscience), CD137 PE (eBioscience), CD3 PerCP (BD Biosciences), NK1.1 APC (BD Biosciences), and F4/80 APC (eBioscience). Stained cells were collected on an FACSCalibur or a LSRII 3-laser cytometer (BD Biosciences) and data were analyzed using Cytobank software (http://www.cytobank.org).33

Statistical analysis

Prism software Version 5.0 (GraphPad) was used to analyze tumor growth and luciferase light units and to determine the statistical significance of differences between groups by applying an unpaired Student t test. Kaplan-Meier plots were used to analyze survival. Correlation coefficients were calculated for comparison of CTCs and percent CD137 expression. Comparisons of survival curves were made using the log-rank test. P values < .05 were considered significant. For tumor burdens, comparisons of means were done by analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Results

Rituximab induces CD137 up-regulation on human NK cells in the presence of CD20+ tumor B cells

Human NK cells from healthy subjects were exposed to rituximab-coated malignant B-cell lines. These cells were incubated in vitro either with rituximab or with trastuzumab, a humanized IgG1 antibody against human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 that is not expressed by B-cell lymphomas. After 24 hours, CD137 expression remained negative to minimal on NK cells in the absence of mAb or in the presence of trastuzumab. Exposure of NK cells to rituximab in the presence of a CD20− B-cell line had no effect on CD137 expression by the NK cells. In contrast, rituximab together with CD20+ B-cell lines induced significant CD137 up-regulation on NK cells (Figure 1A-B). This enhanced expression of CD137 occurred with purified NK cells (supplemental Figure 1A, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article), as observed in PBMCs, and predominantly in the CD56dim subset of NK cells (Figure 1C).

Rituximab induces CD137 up-regulation on human NK cells after incubation with CD20+ tumor B cells. Peripheral blood from 3 healthy donors was analyzed for CD137 expression on CD3−CD56+ NK cells after 24-hour culture with lymphoma cell lines and trastuzumab or rituximab. (A) Percentage of CD137+ cells among CD3−CD56+ NK cells from 3 healthy donors cultured with a CD20− lymphoma cell line (OCI-Ly19) or CD20+ lymphoma cell lines (Ramos, DHL-4, Raji). (B) CD20 surface expression on lymphoma cell lines (OCI-Ly19, Ramos, DHL-4, Raji). Histograms were colored according to the log10-fold increase in MFI of lymphoma cell lines relative to isotype. (C) CD137 expression on the NK-cell subsets CD3−CD56bright and CD3−CD56dim from a representative healthy donor after 24-hour culture with the CD20+ lymphoma cell line Ramos and rituximab.

Rituximab induces CD137 up-regulation on human NK cells after incubation with CD20+ tumor B cells. Peripheral blood from 3 healthy donors was analyzed for CD137 expression on CD3−CD56+ NK cells after 24-hour culture with lymphoma cell lines and trastuzumab or rituximab. (A) Percentage of CD137+ cells among CD3−CD56+ NK cells from 3 healthy donors cultured with a CD20− lymphoma cell line (OCI-Ly19) or CD20+ lymphoma cell lines (Ramos, DHL-4, Raji). (B) CD20 surface expression on lymphoma cell lines (OCI-Ly19, Ramos, DHL-4, Raji). Histograms were colored according to the log10-fold increase in MFI of lymphoma cell lines relative to isotype. (C) CD137 expression on the NK-cell subsets CD3−CD56bright and CD3−CD56dim from a representative healthy donor after 24-hour culture with the CD20+ lymphoma cell line Ramos and rituximab.

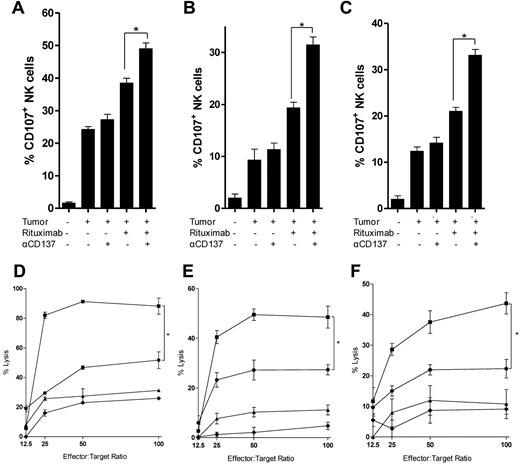

Anti-CD137 mAb increases rituximab-mediated NK-cell degranulation and cytotoxicity

We next investigated whether anti-CD137 agonistic mAb could enhance rituximab-mediated NK-cell function, specifically degranulation and cytotoxicity. We used rituximab together with CD20+ lymphoma cell lines (Raji, Ramos, and DHL-4) to induce CD107a expression on NK cells as a marker of granule mobilization.34 We found that rituximab-induced degranulation could be significantly enhanced by anti-CD137 mAb (Figure 2A-C). 4B4-1, an agonistic, ligand-blocking, IgG1 anti-CD137 mAb, similarly enhanced degranulation, whereas no effect of BBK-2, an antagonistic, ligand-blocking, IgG1 anti-CD137 mAb, was observed (data not shown). Interferon-γ was also increased by anti-CD137 mAb (supplemental Figure 2A). We then assessed the effect of anti-CD137 mAb on rituximab-induced ADCC. Because CD137 is not expressed on resting NK cells, total PBMCs were first preactivated for 24 hours with rituximab-coated lymphoma cells (Raji, Ramos, and DHL-4). This time point was chosen because CD137 expression on NK cells reaches a plateau after 24 hours of activation (supplemental Figure 1B). Preactivation allowed significant up-regulation of CD137 on NK cells (supplemental Figure 1C). NK cells were then purified and cultured with 51Cr-labeled lymphoma cells and rituximab in the presence or absence of anti-CD137 mAb. The addition of anti-CD137 mAb significantly increased rituximab-induced ADCC compared with rituximab alone against Raji, Ramos, and DH-4 (Figure 2D-F). Preactivation of NK cells was necessary to observe increased rituximab-induced ADCC with anti-CD137 mAb and rituximab (supplemental Figure 2C).

Anti-CD137 agonistic mAb increases rituximab-mediated NK-cell cytotoxicity on tumor cells. NK cells isolated and purified from the peripheral blood of healthy donors were analyzed for degranulation by CD107a mobilization after 24-hour culture in 5 conditions: medium alone; CD20+ lymphoma cell line (Raji, Ramos, DHL-4); tumor and rituximab; tumor and anti-CD137 antibody; or tumor, rituximab, and anti-CD137 agonistic antibody. (A) Raji, *P = .01. (B) Ramos, *P = .003. (C) DHL-4, *P = .002. A representative flow cytometric plot of CD107a expression with Ramos target cells is shown in supplemental Figure 3. NK-cell cytotoxicity on Raji, Ramos, and DHL-4 tumor cells was analyzed in a chromium-release assay (D-F). Preactivated NK cells (as described in “Methods”) were purified before being incubated with chromium-labeled Raji, Ramos, and DHL-4 cells for 4 hours. (D-F) Percent lysis of target cells by chromium release at varying effector (activated NK cells)-to-target (Raji) cell ratios cultured with medium alone (♦), anti-CD137 (▴), rituximab (●), or rituximab and anti-CD137(■) antibodies. (D) Raji, *P = .01. (E) Ramos, *P = .01. (F) DHL-4, *P = .009.

Anti-CD137 agonistic mAb increases rituximab-mediated NK-cell cytotoxicity on tumor cells. NK cells isolated and purified from the peripheral blood of healthy donors were analyzed for degranulation by CD107a mobilization after 24-hour culture in 5 conditions: medium alone; CD20+ lymphoma cell line (Raji, Ramos, DHL-4); tumor and rituximab; tumor and anti-CD137 antibody; or tumor, rituximab, and anti-CD137 agonistic antibody. (A) Raji, *P = .01. (B) Ramos, *P = .003. (C) DHL-4, *P = .002. A representative flow cytometric plot of CD107a expression with Ramos target cells is shown in supplemental Figure 3. NK-cell cytotoxicity on Raji, Ramos, and DHL-4 tumor cells was analyzed in a chromium-release assay (D-F). Preactivated NK cells (as described in “Methods”) were purified before being incubated with chromium-labeled Raji, Ramos, and DHL-4 cells for 4 hours. (D-F) Percent lysis of target cells by chromium release at varying effector (activated NK cells)-to-target (Raji) cell ratios cultured with medium alone (♦), anti-CD137 (▴), rituximab (●), or rituximab and anti-CD137(■) antibodies. (D) Raji, *P = .01. (E) Ramos, *P = .01. (F) DHL-4, *P = .009.

Anti-CD137 mAb potentiates antilymphoma activity of anti-CD20 mAb in vivo

To test whether treatment with anti-CD137 mAb would enhance the antilymphoma activity of anti-CD20 mAb in vivo, we used a mouse lymphoma known to be responsive to a mouse anti–mouse CD20 mAb.12 The mechanism of the antilymphoma effect in this system is known to be dependent on FcR expression, so it provides an opportunity to test the additional benefit of anti-CD137 mAb in a therapeutic tumor model.

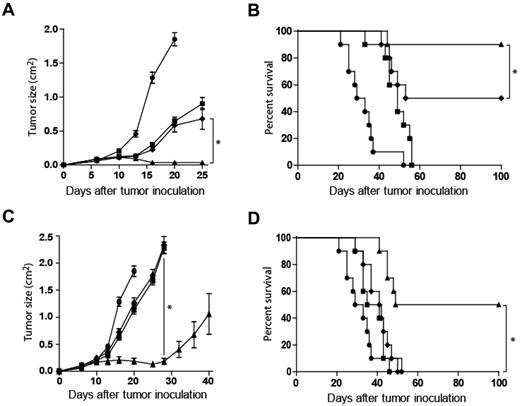

C57BL/6 mice were inoculated subcutaneously with syngeneic BL3750 lymphoma tumor cells. Mice then received rat IgG control on day 3, anti-CD20 mAb on day 3, anti-CD137 mAb on day 4, or anti-CD20 mAb on day 3 and anti-CD137 mAb on day 4 after tumor inoculation. In the combination-antibody group, anti-CD137 mAb was administered 24 hours after anti-CD20 mAb to allow up-regulation of CD137 expression. Although anti-CD20 and anti-CD137 mAbs both had antitumor activity when used as single agents, their combination significantly enhanced tumor regression and survival (Figure 3A-B). To determine activity against well-established tumors, therapy was delayed until day 8, resulting in decreased efficacy of both single agents and the combination. Anti-CD20 and anti-CD137 mAbs as monotherapy on day 8 or 9, respectively, minimally delayed tumor growth (Figure 3C). Anti-CD20 mAb on day 8 followed by anti-CD137 mAb on day 9 resulted in transient tumor regression in all mice and complete regression with prolonged survival among half of combination-treated mice (Figure 3C-D). Combination therapy at later time points, initiation of treatment on day 12 or 15, was more effective than either single-agent treatment, however, the efficacy of each therapy was further reduced (data not shown).

Anti-CD137 agonistic mAb enhances antilymphoma activity of murine anti-CD20 mAb in vivo. C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with 5 × 106 BL3750 lymphoma tumor cells subcutaneously on the abdomen. (A-B) After tumor inoculation, mice received rat IgG control on day 3 (●), anti-CD20 antibody on day 3 (■), anti-CD137 antibody on day 4 (♦), or anti-CD20 antibody on day 3 and anti-CD137 antibody on day 4 (▴). Mice (10 per group) were then monitored for tumor growth (A; *P < .001) and overall survival (B; *P = .048). (C-D) Tumor growth and survival with identical treatment sequence but with treatment delayed until day 8 after tumor inoculation. Mice received rat IgG control on day 8 (●), anti-CD20 antibody on day 8 (■), anti-CD137 antibody on day 9 (♦), or anti-CD20 antibody on day 8 and anti-CD137 antibody on day 9 (▴). Mice (10 per group) were then monitored for tumor growth (C; *P < .001) and overall survival (D; *P < .001).

Anti-CD137 agonistic mAb enhances antilymphoma activity of murine anti-CD20 mAb in vivo. C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with 5 × 106 BL3750 lymphoma tumor cells subcutaneously on the abdomen. (A-B) After tumor inoculation, mice received rat IgG control on day 3 (●), anti-CD20 antibody on day 3 (■), anti-CD137 antibody on day 4 (♦), or anti-CD20 antibody on day 3 and anti-CD137 antibody on day 4 (▴). Mice (10 per group) were then monitored for tumor growth (A; *P < .001) and overall survival (B; *P = .048). (C-D) Tumor growth and survival with identical treatment sequence but with treatment delayed until day 8 after tumor inoculation. Mice received rat IgG control on day 8 (●), anti-CD20 antibody on day 8 (■), anti-CD137 antibody on day 9 (♦), or anti-CD20 antibody on day 8 and anti-CD137 antibody on day 9 (▴). Mice (10 per group) were then monitored for tumor growth (C; *P < .001) and overall survival (D; *P < .001).

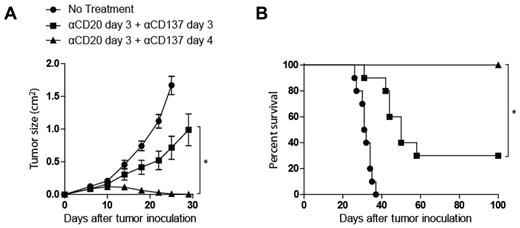

Anti-CD20 and anti-CD137 mAb combination activity is enhanced by sequential administration

The combined antibody therapy was next tested with simultaneous administration of both antibodies on day 3 to assess if the in vivo–enhanced activity of anti-CD20 and anti-CD137 mAbs required anti-CD20 mAb activation of NK cells before anti-CD137 mAb treatment. Synergistic antitumor activity was observed when anti-CD20 mAb was administered before anti-CD137 mAb (Figure 4). Significantly improved antitumor activity was also observed at a delayed treatment time point (8 days after tumor inoculation) for large tumors when anti-CD20 mAb was administered 24 hours before anti-CD137 mAb (Figure 3C-D).

Anti-CD20 and anti-CD137 mAbs combination activity is enhanced by sequential mAb administration. C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with 5 × 106 BL3750 lymphoma tumor cells subcutaneously on the abdomen. After tumor inoculation, mice received rat IgG control on day 3 (●), anti-CD20 mAb on day 3 and anti-CD137 mAb on day 4 (▴), or anti-CD20 mAb on day 3 and anti-CD137 mAb on day 3 (■). Mice (10 per group) were then monitored for tumor growth (A; *P < .001) and overall survival (B; * P = .001).

Anti-CD20 and anti-CD137 mAbs combination activity is enhanced by sequential mAb administration. C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with 5 × 106 BL3750 lymphoma tumor cells subcutaneously on the abdomen. After tumor inoculation, mice received rat IgG control on day 3 (●), anti-CD20 mAb on day 3 and anti-CD137 mAb on day 4 (▴), or anti-CD20 mAb on day 3 and anti-CD137 mAb on day 3 (■). Mice (10 per group) were then monitored for tumor growth (A; *P < .001) and overall survival (B; * P = .001).

Antilymphoma activity of combination therapy requires NK cells and macrophages

To further investigate the mechanism of action of anti-CD20 and anti-CD137 mAb combination therapy, we next determined whether anti-CD20 mAb was capable of inducing CD137 up-regulation in vivo, similar to what we had observed in vitro. Lymphoma-bearing mice were treated on day 3 after tumor inoculation with IgG control or anti-CD20 antibody. Peripheral blood and primary tumors were collected and cell subsets (NK cells, macrophages, and T cells) were analyzed for CD137 expression. Consistent with our previous in vitro findings, we observed that NK cells up-regulated CD137 on their surface after in vivo exposure to anti-CD20 mAb (Figure 5A-B). In vitro culture of purified murine NK cells with BL3750 tumor at a 1:1 ratio, similarly resulted in increased NK-cell CD137 expression with the addition of anti-CD20 mAb after 24 hours (7.9%-73.5%, P < .001). Relative to circulating monocytes, tumor-infiltrating macrophages expressed high levels of CD137, which was nonsignificantly increased after anti-CD20 mAb administration. CD4 T cells and CD8 T cells did not increase the expression of CD137 in response to anti-CD20 mAb at the same time points. To confirm the role of NK cells and macrophages in the therapeutic effect, we next performed a depletion experiment. We found that NK-cell and macrophage depletion, and not CD8 T-cell depletion, abrogated the therapeutic efficacy of anti-CD20 and anti-CD137 combination therapy (Figure 5C-D). Three of 10 mice depleted of CD8 T cells experienced late (> 40 days after tumor inoculation) relapses (Figure 5C-D).

Enhancement of the antilymphoma activity of anti-CD20 mAb by anti-CD137 agonistic mAb is dependent on NK cells and macrophages. (A) Peripheral blood cell subsets from lymphoma-bearing C57BL/6 mice 4 days after tumor inoculation treated on day 3 with either IgG control or anti-CD20 antibody were analyzed for CD137 expression on CD3−NK1.1+ NK cells (NK), F4/80+ macrophages (Mϕ), CD3+CD8+ T cells (CD8), and CD3+CD4+ T cells (CD4) (n = 3 mice per group, *P = .001). (B) Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes from lymphoma-bearing C57BL/6 mice 7 days after tumor inoculation treated on day 3 with either IgG control or anti-CD20 antibody were analyzed for CD137 expression on CD3−NK1.1+ NK cells (NK), F4/80+ macrophages (Mϕ), CD3+CD8+ T cells (CD8), and CD3+CD4+ T cells (CD4) (n = 3 mice per group, *P = .012; NS, not significant). (C-D) C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with 5 × 106 BL3750 lymphoma tumor cells. After tumor inoculation, mice received rat IgG control on day 3 (●), anti-Asialo-GM1 on days −1, 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 with anti-CD20 antibody on day 3 and anti-CD137 antibody on day 4 (■), liposomal clodronate on days −2, 0, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 with anti-CD20 antibody on day 3 and anti-CD137 antibody on day 4 (▾), anti-CD8 mAb on days −1, 0, 5, 10,15, 20, and 25 with anti-CD20 antibody on day 3 and anti-CD137 antibody on day 4 (♦), or anti-CD20 antibody on day 3 and anti-CD137 antibody on day 4 (▴). Mice (10 per group) were then monitored for tumor growth (C; *P = .002) and overall survival (D; *P < .001).

Enhancement of the antilymphoma activity of anti-CD20 mAb by anti-CD137 agonistic mAb is dependent on NK cells and macrophages. (A) Peripheral blood cell subsets from lymphoma-bearing C57BL/6 mice 4 days after tumor inoculation treated on day 3 with either IgG control or anti-CD20 antibody were analyzed for CD137 expression on CD3−NK1.1+ NK cells (NK), F4/80+ macrophages (Mϕ), CD3+CD8+ T cells (CD8), and CD3+CD4+ T cells (CD4) (n = 3 mice per group, *P = .001). (B) Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes from lymphoma-bearing C57BL/6 mice 7 days after tumor inoculation treated on day 3 with either IgG control or anti-CD20 antibody were analyzed for CD137 expression on CD3−NK1.1+ NK cells (NK), F4/80+ macrophages (Mϕ), CD3+CD8+ T cells (CD8), and CD3+CD4+ T cells (CD4) (n = 3 mice per group, *P = .012; NS, not significant). (C-D) C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with 5 × 106 BL3750 lymphoma tumor cells. After tumor inoculation, mice received rat IgG control on day 3 (●), anti-Asialo-GM1 on days −1, 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 with anti-CD20 antibody on day 3 and anti-CD137 antibody on day 4 (■), liposomal clodronate on days −2, 0, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 with anti-CD20 antibody on day 3 and anti-CD137 antibody on day 4 (▾), anti-CD8 mAb on days −1, 0, 5, 10,15, 20, and 25 with anti-CD20 antibody on day 3 and anti-CD137 antibody on day 4 (♦), or anti-CD20 antibody on day 3 and anti-CD137 antibody on day 4 (▴). Mice (10 per group) were then monitored for tumor growth (C; *P = .002) and overall survival (D; *P < .001).

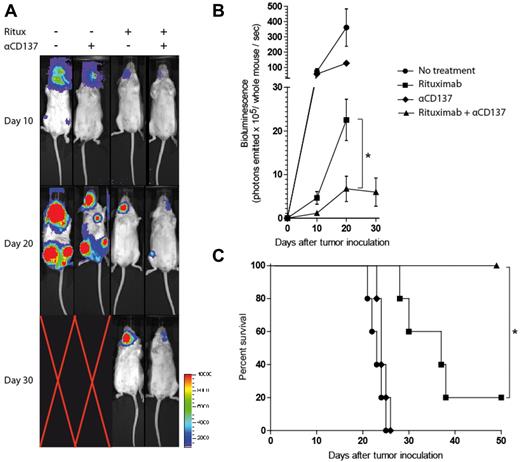

Anti-CD137 mAb potentiates rituximab activity in a disseminated human lymphoma xenotransplant model

To confirm that the innate immune system is sufficient in mediating the antilymphoma activity of human anti-CD20 (rituximab) and anti-CD137 combination therapy in vivo, we used a SCID mouse, human lymphoma xenotransplant model. SCID mice lack B and T cells but maintain a competent NK-cell and macrophage population, allowing us to determine whether these cell populations mediate the therapeutic effect. SCID mice were inoculated intravenously through the retro-orbital sinus with luciferase-labeled Raji cells. Mice then received rat IgG control on day 3, rituximab on day 3, anti-CD137 mAb on day 4, or rituximab on day 3 and anti-CD137 mAb on day 4 after tumor inoculation, and this treatment was repeated weekly for 4 weeks. A 5-fold increase in the percentage of peripheral blood NK cells expressing CD137 was observed 24 hours after rituximab treatment (data not shown). The combination of anti-CD137 agonistic mAb with rituximab significantly improved the rate of tumor regression and survival over rituximab alone (Figure 6).

Anti-CD137 agonistic mAb enhances antilymphoma activity of rituximab in vivo in a disseminated human lymphoma xenotransplant model. SCID mice were inoculated with 3 × 106 luciferase-labeled Raji lymphoma tumor cells intravenously through the retro-orbital sinus. After tumor inoculation, mice received rat IgG control on day 3 (●), rituximab on day 3 (■), anti-CD137 antibody on day 4 (♦), or rituximab on day 3 and anti-CD137 antibody on day 4 (▴). Treatment was continued weekly for a total of 4 weeks. (A) Luciferase imaging of representative mice 10, 20, and 30 days after treatment are shown. Mice (5 per group) were then monitored for quantified bioluminescence (B; *P = .001) and overall survival (C; *P = .013).

Anti-CD137 agonistic mAb enhances antilymphoma activity of rituximab in vivo in a disseminated human lymphoma xenotransplant model. SCID mice were inoculated with 3 × 106 luciferase-labeled Raji lymphoma tumor cells intravenously through the retro-orbital sinus. After tumor inoculation, mice received rat IgG control on day 3 (●), rituximab on day 3 (■), anti-CD137 antibody on day 4 (♦), or rituximab on day 3 and anti-CD137 antibody on day 4 (▴). Treatment was continued weekly for a total of 4 weeks. (A) Luciferase imaging of representative mice 10, 20, and 30 days after treatment are shown. Mice (5 per group) were then monitored for quantified bioluminescence (B; *P = .001) and overall survival (C; *P = .013).

Rituximab-coated, autologous lymphoma cells induce CD137 up-regulation on NK cells from human patients with B-cell malignancies

We first identified patients with B-cell lymphomas who had CTCs. To mimic the in vivo interaction between NK cells and tumor cells in the presence of rituximab, we then incubated patient PBMCs that contained variable numbers of CTCs for 24 hours in vitro either with rituximab or with trastuzumab. As we had observed using NK cells from healthy subjects, CD137 expression remained negative in the absence of mAb or in the presence of trastuzumab. In contrast, the inclusion of rituximab induced significant up-regulation of CD137 with a concomitant decrease in CD16 expression (Figure 7A). Similar results were observed across 25 patient samples with a variety of histologies (Figure 7B). The degree of CD137 up-regulation was correlated with percent CTCs among follicular, diffuse large B-cell, marginal zone, chronic lymphocytic, and CD20+ acute lymphoblastic leukemias and lymphomas (Figure 7C). This trend was not observed among cases of mantle cell histology.

Rituximab-coated, autologous lymphoma cells induce CD137 up-regulation on NK cells from human patients with B-cell malignancies. (A-B) Peripheral blood from patients with B-cell malignancies and CTCs were analyzed for CD137 expression on CD3−CD56+ NK cells after 24-hour culture with medium alone, trastuzumab, or rituximab. (A) CD16 and CD137 expression on CD3−CD56+ NK cells for a patient with marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) with 70% CTCs. (B) Percentage of CD137+ cells among CD3−CD56+ NK cells in a cohort of 25 patients with follicular lymphoma (FL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), MZL, mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), or CD20+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). (C) Correlation (r2 = 0.87, P < .001) between the percentage of peripheral blood CTCs and CD137 surface expression on CD3−CD56+ NK cells after 24-hour culture with rituximab from patient samples with FL (◐ ), CLL (●), MZL (◒), DLBCL (◑), or CD20+ ALL (◓).

Rituximab-coated, autologous lymphoma cells induce CD137 up-regulation on NK cells from human patients with B-cell malignancies. (A-B) Peripheral blood from patients with B-cell malignancies and CTCs were analyzed for CD137 expression on CD3−CD56+ NK cells after 24-hour culture with medium alone, trastuzumab, or rituximab. (A) CD16 and CD137 expression on CD3−CD56+ NK cells for a patient with marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) with 70% CTCs. (B) Percentage of CD137+ cells among CD3−CD56+ NK cells in a cohort of 25 patients with follicular lymphoma (FL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), MZL, mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), or CD20+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). (C) Correlation (r2 = 0.87, P < .001) between the percentage of peripheral blood CTCs and CD137 surface expression on CD3−CD56+ NK cells after 24-hour culture with rituximab from patient samples with FL (◐ ), CLL (●), MZL (◒), DLBCL (◑), or CD20+ ALL (◓).

Discussion

Since the approval and widespread adoption of rituximab for the treatment of lymphoma, many attempts have been made to enhance its efficacy.5 Among these, strategies to enhance rituximab-mediated ADCC are particularly appealing. To date, most of these approaches have focused on the mAb itself by molecular engineering of the biochemical structure to enhance the Fc-FcγR interaction.5 In the present study, we developed an alternative approach to enhancing rituximab's efficacy by stimulating effector NK cells implicated in tumor cell killing through ADCC.

We demonstrated that recognition of rituximab-coated tumor B cells induces the up-regulation of CD137 on NK cells, a phenomenon that is time dependent and peaks at 24 hours. Consistent with this finding, a study by Lin et al showed that an immobilized IgG1 antibody was capable of up-regulating CD137 on the surface of interleukin-2 (IL-2)–stimulated NK cells over a similar time course.16 Whereas the capacity of IL-2 stimulation alone to induce CD137 expression is debated,16,35 we showed in the absence of IL-2 that rituximab-coated tumor cells induce up-regulation of CD137 on human NK cells in an antibody- and tumor-specific manner. Raji cells induce CD137 in the absence of rituximab coating, which is seen to a lesser degree with Ramos or DHL4. In addition to CD137 up-regulation, we observed a concurrent down-regulation of CD16 among all NK cells, which had previously been shown to be internalized after Fc-FcγR binding.36,37 It is likely that CD137 up-regulation is secondary to rituximab binding on NK cells through the FcγR, as supported by Melero et al's prior report.38 Given these observations, we predict that NK cells stimulated by rituximab bound to CD20-expressing cells up-regulate CD137 in vivo. Therefore, we expect anti-CD137 mAb to preferentially target activated NK cells expressing CD137, including NK cells implicated in tumor-directed ADCC, while sparing inactive or resting NK cells, thus limiting the potential off-target toxicity of anti-CD137 mAb.

After CD137 up-regulation on NK cells, we showed that stimulation of this target with an agonistic mAb enhanced NK-cell activity, as measured by granule mobilization and killing of rituximab-coated tumor cells (ADCC). In vitro ADCC was assessed by chromium-release assays in which relatively high ratios of CD137-expressing, preactivated effector-to-target ratios were required. This may be because of decreased NK-cell fitness resulting from the additional time in culture for preactivation without exogenous cytokines.16 However, by using purified and preactivated NK cells in vitro, the predominant mechanism of antitumor activity is limited to ADCC. This is supported by the observation that the population of NK cells up-regulating CD137 was the CD56dim subset, which is known to preferentially mediate ADCC.39 Anti-CD137 mAb enhanced ADCC against lymphoma cell lines independently of target cell expression of CD137 ligand. CD137-ligand expression by tumors in acute myeloid leukemia has been reported to directly influence spontaneous cytotoxicity of NK cells.35 Baessler et al observed decreased spontaneous cytotoxicity against CD137 ligand expressing acute myeloid leukemia posited to result from inhibitory reverse signaling through the CD137 receptor on the NK-cell interaction with the CD137 ligand. Because spontaneous cytotoxicity and ADCC are independent mechanisms of NK-cell cytotoxicity, our observations cannot be directly compared with the findings of Baessler.

To explore in vivo activity, specifically the capacity of anti-CD137 mAb therapy to potentiate the antilymphoma activity of anti-CD20 mAb, we first used an immunocompetent syngeneic mouse lymphoma model, which was selected because it is the only available model with which to test syngeneic anti-CD20 mAbs. Consistent with our human in vitro data, we showed that, although resting NK cells do not express CD137, in vivo administration of anti-CD20 mAb in mice up-regulates CD137 on the surface of NK cells. This might explain why anti-CD20 mAb needs to be administered before anti-CD137 mAb to see optimal therapeutic benefit. Although circulating monocyte expression of CD137 did not increase after anti-CD20 mAb treatment, the majority of intratumoral macrophages expressed CD137. In addition to being required for the efficacy of anti-CD20 mAb,12 monocytes/macrophages may also participate in the additional benefit of anti-CD137 combination therapy. Consistent with these observations, we showed that the initial efficacy of this combination is dependent on NK cells and macrophages. Given that the therapeutic anti-CD20 mAb efficiently depletes B cells, the initial antitumor activity of the combination is unlikely to be dependent on B-cell function. The efficacy observed using a human lymphoma xenotransplant model in immunodeficient SCID mice, which maintain functional NK cells, macrophages, and complement, further shows that the innate immune system efficiently mediates the initial antilymphoma activity of the combination therapy. Despite the limitations of this model and its focus on the innate immune system, it and similar models are commonly used as a preclinical test of the efficacy of new anti-CD20 mAbs among other antilymphoma mAbs active by ADCC.7,40 Interestingly, complete tumor regression was not observed in the xenotransplant SCID model, and a limited number of relapses occurred among CD8 T-cell–depleted mice in the immunocompetent syngeneic model, suggesting that long-term immunity requires a competent adaptive immune response.

Patients with circulating tumor cells were studied to determine whether NK cells from patients with B-cell lymphomas similarly up-regulate CD137. We observed variation between patients in the level of CD137 expression on NK cells after exposure to rituximab. Differences in histology and percentage of CTCs may partially account for this variance, given the observed correlation between CTC and CD137 expression levels. In addition to the variable histologies and effector-to-target ratios represented by percent CTCs, other factors that may play a role in this variance include the density of surface CD20 molecules on tumor B cells or variable sensitivity of NK cells to rituximab-bound tumor cells.15 These factors may also explain why CD137 up-regulation is greater after exposure to rituximab-bound tumor cells compared with normal B cells. Given the heterogeneity in the observed CD137 up-regulation in patient samples, an important question is whether CD137 up-regulation after anti-CD20 mAb treatment could serve as a biomarker of response to anti-CD137 therapy in combination with rituximab. If so, to what extent are Fc polymorphisms responsible for this heterogeneity? And, although speculative, could patients be selectively screened for clinical trials with anti-CD20 and anti-CD137 mAb combination therapy based on the ability of their NK cells to undergo CD137 up-regulation after exposure to antibody-coated tumor cells? To validate this observation and to better understand the kinetics and inter-patient heterogeneity in vivo, a clinical study of CD137 expression after rituximab therapy is ongoing.

In conclusion, the results of our study suggest an innovative strategy to enhance rituximab's efficacy based on a sequential approach targeting both the tumor and the immune system. Given first, rituximab induces up-regulation of CD137 on NK cells involved in ADCC. Subsequently, an agonistic anti-CD137 mAb is administered to enhance NK-cell killing of rituximab-coated tumor cells. Therefore, NK cells stimulated by rituximab-bound tumor cells and consequently involved in rituximab-induced ADCC, will be targeted by the immunostimulatory mAb. This strategy is in contrast to approaches designed to stimulate NK cells nonspecifically, such as those using IL-2,41,42 IL-12,43 or blocking antibodies against constitutively expressed inhibitory receptors such as anti-KIR mAbs.44 These strategies result in dose-limiting toxicity because of systemic stimulation of NK cells. The combination of rituximab and anti-CD137 mAb should be well-tolerated compared with currently approved NK-cell agonists such as IL-2 or to conventional, cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Despite the focus of our work on ADCC, the effects of anti-CD137 mAb on non-NK cells will be important in the clinical development of anti-CD137 mAb therapy in B-cell malignancies. Activated, normal B cells are reported to up-regulate CD137 and to proliferate after stimulation via CD137-ligand engagement,45 raising concern for potential stimulation of B-cell tumors with anti-CD137 mAb therapy. However, we previously evaluated multiple histologic subtypes of B-cell lymphoma and did not observe expression of CD137 by malignant B cells.23 As suggested by other studies, rituximab-induced killing may trigger an adaptive immune response5,46 that might be further improved by CD137 stimulation of activated dendritic cells47,48 and T cells, including antigen-specific memory T cells.20,29,48 In preclinical models, anti-CD137 mAb stimulation of this immune subset, specifically CD8 T cells, resulted in effective antilymphoma single-agent therapy,23 suggesting that anti-CD137 mAb may be effective as a monotherapy for B-cell malignancies. This is consistent with our observation of antilymphoma activity limited to immunocompetent mice, and not SCID mice, with anti-CD137 mAb monotherapy. However, stimulation of CD8 T cells also appears to be responsible for the toxicity to hepatocytes observed in preclinical mouse models49 and among 11% of patients with melanoma, renal cell, and ovarian tumors in a phase 1 trial of anti-CD137 mAb (BMS-663513).50 A clinical trial as a single agent and in combination with rituximab is needed to determine the therapeutic window of anti-CD137 mAb therapy. Corollary studies of immune, hematopoietic, and nonhematopoietic cells performed in parallel with future clinical trials will clarify the significance of the diverse repertoire of cells targeted by anti-CD137 mAb therapy.

Overall, our study demonstrates the promise of anti-CD137 agonistic mAb to enhance the efficacy of rituximab therapy for the treatment of lymphoma. These results establish a proof of concept for the enhancement of rituximab through immunomodulation of effector cells, and support the testing of anti-CD137 agonistic mAb in combination with rituximab in clinical trials for patients with lymphoma.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Christopher Contag for providing the GFP-luciferase construct.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants CA34233 and, CA33399 (to R.L.) and AI56363 and AI057157 (to T.F.T.) and by a Leukemia & Lymphoma Society Specialized Center of Research (SCOR) grant. M.J.G. is supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Research Training Fellowship. R.H. is supported by fellowships from the Foundation de France and the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: H.E.K., R.H., M.J.G., and K.W. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; S.C., A.A.A., J.B., and R.P. contributed patient samples and designed and performed experiments; A.M. and D.C. designed and performed experiments; M.P.C. generated the luciferase-labeled Raji cells; L.C. provided the 2A hybridoma and reviewed data and the paper; T.F.T. provided the MB20-11 antibody and BL3750 tumor cell line, and reviewed data and the paper; and R.L. designed experiments, reviewed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ronald Levy, MD, Professor of Medicine, Chief, Division of Oncology, 269 Campus Dr, CCSR 1105, Stanford University Medical Center, Stanford, CA 94305-5151; e-mail: levy@stanford.edu.

References

Author notes

H.E.K. and R.H. contributed equally to this study.