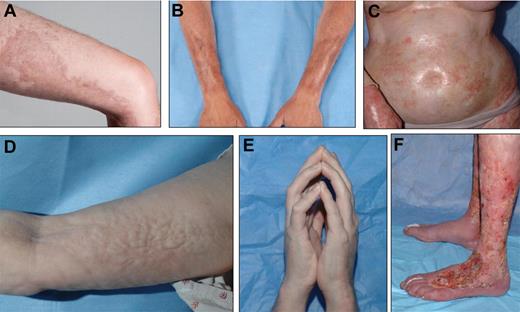

In this issue of Blood, Martires et al report on the risk factors for sclerotic skin manifestations in 206 patients with established chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD).1 Sclerotic skin changes are one of the most dreaded manifestations of cGVHD, encasing the patients in unmovable skin. Patients become progressively immobilized in skin like layers of cement, making normal, daily living impossible (see figure).

Although this late manifestation of cGVHD has long been recognized, little is known about the pathophysiology or risk factors for this particular manifestation of cGVHD. Martires and colleagues have given the cement a firm whack by looking at patients with established cGVHD (median treatments = 4) referred to the National Institutes of Health for a multidisciplinary evaluation in a single-visit, cross-sectional design study of the risk factors and laboratory markers of cGVHD.1 Sclerotic changes were found in 109 of the 206 patients. As even large centers have only a few patients with sclerotic cGVHD (scGVHD) at any one time (roughly 10%–15% of patients with cGVHD), this is a remarkable sample size. The investigators found that scGVHD was associated with higher platelet count and serum C3 complement, and decreased forced vital capacity. As expected, patients with scGVHD had significant impairments of joint range of motion and grip strength. Total body irradiation (TBI) was associated with the development of scGVHD, especially when used in reduced intensity conditioning regimens. Higher body surface area involvement was associated with poorer survival.

Localized, bound-down, thickened, hyperpigmented plaques on the thigh (A) and forearms (B) resemble morphea/localized scleroderma. (C) Widespread shiny indurated skin on the torso resembles generalized systemic sclerosis and may lead to restricted chest wall expansion. Subcutaneous and fascial fibrosis results in an irregular, rippled appearance to the skin, resembling eosinophilic fasciitis (D) and may result in joint contractures, including the prayer sign (E). (F) Skin breakdown and poor wound healing is a complication of long-standing ScGVHD, particularly of the lower extremities, and may lead to increased risk of systemic infection. See the complete article by Martires et al on page 4250.

Localized, bound-down, thickened, hyperpigmented plaques on the thigh (A) and forearms (B) resemble morphea/localized scleroderma. (C) Widespread shiny indurated skin on the torso resembles generalized systemic sclerosis and may lead to restricted chest wall expansion. Subcutaneous and fascial fibrosis results in an irregular, rippled appearance to the skin, resembling eosinophilic fasciitis (D) and may result in joint contractures, including the prayer sign (E). (F) Skin breakdown and poor wound healing is a complication of long-standing ScGVHD, particularly of the lower extremities, and may lead to increased risk of systemic infection. See the complete article by Martires et al on page 4250.

The pathogenesis of cGVHD is poorly understood. Much of the recent work on the pathophysiology of cGVHD has concentrated on the role of perturbed B-cell homeostasis, resulting in the release and persistence of auto-reactive B cells.2-4 Many auto-antibodies have been identified in patients with cGHVD, including stimulatory antiplatelet derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFRA) antibodies.5 In vitro, these antibodies have been shown to induce PDGFRA phosphorylation, reactive oxygen species generation, and increased α-actin and collagen expression.6 These processes have been implicated in the pathogenesis of systemic scleroderma, and strongly suggest that these antibodies have a role in the pathogenesis of scGVHD. Imatinib, a drug that inhibits the phosphorylation of the tyrosine kinases PDGFR, c-KIT, BCR-ABL, DDR1, and DDR2, was first reported to be useful in the treatment of scGVHD in this journal.7,8 A recent study in Blood found the surprising result that responses to imatinib treatment did not correlate with anti-PDGFRA antibodies.9 This strongly suggests that there are multiple pathways involved both with the generation of sclerosis in scGVHD and in response to treatment with imatinib. These data are supported by the Martires study that found no association of scGVHD with a panel of autoantibodies. So, does this mean B cells play no role in scGVHD? No, it means that cGVHD is a complex disorder where the pathways involved in the initiation of the disease may not be the same as those that perpetuate it.

This is why the Martires study is important; it provides clues to help investigators explore sclerotic changes. For example, the authors report an association with an elevated platelet count and C3 and scGVDH. It is not known at this point if these findings represent nonspecific responses or mediators themselves (via release of growth factors causing the sclerosis). There are also clues in the data on the initiation of scGVHD and an association with TBI. This finding, if confirmed, could lead to prevention strategies (different preparative regimens) and new lines of treatment.

The strength of this study—its snapshot design of a single, detailed visit—is also its weakness. The design does not allow one to study the evolution of scGVH. There have been many single-center studies trying to describe biomarkers for the development of cGVHD. Unfortunately, cGVHD has a wide variety of manifestations and it is far from clear that the pathways involved in scGVHD are the same as those involved in a patient with isolated hepatic cGVHD. Better understanding of this requires following large numbers of patients for years in natural history studies. Fortunately, the Chronic GVHD consortium, under the leadership of Stephanie Lee, has undertaken this comprehensive approach and is following a large group of patients with newly diagnosed and with established cGVHD. The Consortium is both closely documenting the clinical findings at each visit and banking tissue samples for future study. This effort is already producing clinically relevant results,10,11 and will garner a more thorough understanding of the clinical course of the disease while providing samples to better define the underlying pathophysiology. The combination of these 2 approaches (the snapshot and the natural history) is indeed a powerful hammer that hopefully will release these patients, most of whom are cured of their underlying malignancy, from the encasement of scGVHD that has so hampered their lives.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■