Abstract

Anemia of chronic inflammation (ACI) is the most frequent anemia in hospitalized patients and is associated with significant morbidity. A major underlying mechanism of ACI is the retention of iron within cells of the reticuloendothelial system (RES), thus making the metal unavailable for efficient erythropoiesis. This reticuloendothelial iron sequestration is primarily mediated by excess levels of the iron regulatory peptide hepcidin down-regulating the functional expression of the only known cellular iron export protein ferroportin resulting in blockade of iron egress from these cells. Using a well-established rat model of ACI, we herein provide novel evidence for effective treatment of ACI by blocking endogenous hepcidin production using the small molecule dorsomorphin derivative LDN-193189 or the protein soluble hemojuvelin-Fc (HJV.Fc) to inhibit bone morphogenetic protein-Smad mediated signaling required for effective hepcidin transcription. Pharmacologic inhibition of hepcidin expression results in mobilization of iron from the RES, stimulation of erythropoiesis and correction of anemia. Thus, hepcidin lowering agents are a promising new class of pharmacologic drugs to effectively combat ACI.

Introduction

Anemia of chronic inflammation (ACI), also termed anemia of chronic disease, is the most frequent anemia in hospitalized patients and develops in subjects suffering from diseases with associated immune activation, such as infections, autoimmune disorders, cancer and end stage renal disease.1,2 A major cornerstone in the pathophysiology of ACI is iron limited erythropoiesis, caused by iron retention within macrophages.1,3-6 Cytokines and most importantly the acute phase protein hepcidin promote macrophage iron retention by increasing erythrophagocytosis and cellular iron uptake and by blocking iron egress from these cells.5,7-10

The primarily liver derived peptide, hepcidin, exerts regulatory effects on iron homeostasis by binding to ferroportin, the only known iron export protein, thereby leading to ferroportin degradation and subsequently to inhibition of duodenal iron absorption and macrophage iron release.5,6,11,12 The crucial role of hepcidin for the development of macrophage iron retention, hypoferremia and ACI is underscored by the observations that mice overexpressing hepcidin develop severe anemia,7,13 that macrophage iron retention and hyperferritinemia are positively associated with hepcidin formation5,14 and that injection of LPS into healthy volunteers results in hepcidin production and hypoferremia.15

The expression of hepcidin in hepatocytes is regulated by multiple signals.16 Iron overload induces the formation of bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs)17 and activates phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation,17-20 which forms a transcriptional activator complex with Smad4 to stimulate hepcidin transcription.21-23 In mice, BMP6 appears to play a major role in hepcidin regulation, as BMP6 knock out mice have hepcidin deficiency resulting in systemic iron overload.24,25 Hemojuvelin (HJV) or HFE2, a membrane bound GPI-anchored protein26,27 acts as a BMP coreceptor and promotes hepcidin transcription.21 In contrast, a soluble form of HJV (sHJV) blocks BMP6 and inhibits hepcidin expression.28

The inflammation mediated activation of hepcidin is mainly transmitted via the IL6-inducible transcription factor Stat3.29-31 In addition, Stat3 signaling is influenced by BMP dependent Smad activation, but not vice versa, indicating that the BMP/Smad pathway is able to modulate the IL6 inducible Stat3 pathway.22,23

Current available treatment strategies for ACI with erythropoiesis stimulating agents (ESAs), intravenous iron or packed red blood cell transfusions have either a limited success rate in some patients, or harbor potential hazards including risk of infections, mortality, iron overload or recurrence of cancer.1,3,32-35 Thus, novel strategies to treat ACI, which negatively impacts on the quality of life and cardiac performance of patients, are urgently needed.

Because of the central role of hepcidin in the regulation of iron metabolism, inhibition of its biologic activity could be a promising new approach for the treatment of ACI. A recent study in a mouse model of anemia associated with inflammation demonstrated that an anti-hepcidin antibody, in combination with ESA therapy, was effective in ameliorating anemia. However, neither the ESAs nor the anti-hepcidin antibody when applied alone resulted in correction of anemia.36

Here, we have used an alternative approach to block the biologic activity of hepcidin by inhibiting its expression in the liver using small molecule and biologic BMP inhibitors, and studied the therapeutic effectiveness of this strategy in a well-established rat model of ACI. We provide compelling evidence that inhibiting BMP signaling can successfully treat ACI by lowering hepcidin production, with subsequent mobilization of iron from the RES, leading to successful stimulation of erythropoiesis without the need to add ESAs.

Methods

Animals

Female Lewis rats, aged 8-10 weeks, (Charles River Laboratories) were kept on a standard rodent diet (180mg Fe/kg, C1000 from Altromin). The animals had free access to food and water and were housed according to institutional and governmental guidelines in the animal facility of the Medical University of Innsbruck with a 12 hour light-dark cycle and an average temperature of 20°C ± 1°C. Design of the animal experiments was approved by the Austrian Federal Ministry of Science and Research (BMWF-66.011/0060-II/10b/2010 and BMWF-66.011/0061-11/10b/2010)

Female Lewis rats were inoculated on day 0 with a single intraperitoneal injection of Group A Streptococcal Peptidoglycan-Polysaccharide (PG-APS; Lee Laboratories) suspended in 0.85% saline with a total dose of 15μg rhamnose/g body weight. Three weeks after PG-APS administration, animals were tested for the development of anemia and randomized into groups with similar Hb levels. Rats which developed anemia (> 2g/dL drop from baseline range) were designated ACI rats.

For short-term treatment experiments, ACI rats were treated with a single intravenous injection of vehicle (2% 2-hydroxypropyl-B-cyclodextrin [Sigma-Aldrich] in PBS, pH 7.4; n = 5), a single intraperitoneal injection of LDN-193189 (3 mg/kg37 ; n = 6) or a single intravenous injection of soluble human hemojuvelin extracellular domain dimer fused with immunoglobulin Fc on position S398 (HJV.Fc; 20 mg/kg21 ; n = 6). Rats were killed 6 and 24 hours after application, respectively. HJV.Fc protein was provided by Ferrumax Pharmaceuticals Inc. LDN-193189 was custom synthesized, as described by Cuny et al,37 by Shanghai United Pharmatec and dissolved at a concentration of 0.25 mg/mL in 2% 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin.

For long-term treatment experiments, ACI rats were injected at 21 days after PG-APS administration with either vehicle (n = 6 for LDN experiments and n = 10 for HJV.Fc experiments), LDN-193189 (3 mg/kg; n = 6) every second day administrated intraperitoneally or HJV.Fc protein (20 mg/kg; n = 10) twice a week administrated intravenously for an additional 28 days. Throughout the treatment period, a total of 500 μL of blood was collected weekly by puncture of the tail veins for complete blood counts (CBC) and serum iron analysis. CBC analysis was performed on a Vet-ABC Animal blood counter (Scil Animal Care Company). Serum iron was determined by a commercially available colorimetric assay (BioAssay Systems).

After 28 days of treatment (49 days after induction of ACI), all rats were euthanized and tissues were harvested for gene expression and protein analysis.

Cell culture

Primary cell cultures.

The preparation of primary hepatocytes was carried out as described.38 The livers were perfused with a collagenase blend in a recirculating manner from the portal vein to the incised vena cava.

Except for the liver perfusion, all media used were supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/mL) and 2mM glutamine or Glutamax, respectively. The portal vein of deeply anaesthetized (ketamin/xylazine intramuscularly) rats was canulated and the lower vena cava incised. Immediately, perfusion was started with Seglen perfusion buffer39 supplemented with 0.1mM EGTA, 37°C, for 10 minutes at 25 mL/min and then with Seglen Ca2+ containing collagenase buffer at 37°C for 2 minutes in a nonrecirculating manner. The liver was then swiftly excised without disturbing the capsule and the system was switched to recirculation, with collagenase buffer containing 29 μg/mL Liberase Blendzyme 3 (Roche), 37°C, for 10 minutes at 25 mL/min. A sterile filter, but no oxygenation apparatus, was integrated in the tubing.

The liver capsule was then incised in a Petri dish with L-15 (Leibowitz) medium (Gibco), and the cell suspension was carefully filtered through a 100 μm mesh. Hepatocytes were centrifuged at 30g for 3 minutes and once more in Hepatocyte Wash Medium (Gibco). Nonviable and remaining nonparenchymal cells were removed by iso-density Percoll centrifugation in 50% Percoll (GE Healthcare) at 50g for 10 minutes, and the hepatocytes were washed 3 times in Hepatocyte Wash Medium.

The resulting cell suspension had a high purity (> 99%) as determined by light microscopy. The viability of purified hepatocytes was always higher than 90% as determined by trypan blue exclusion.

Cells were transferred to 6-well plates (Falcon) coated with PureCol (Advanced BioMatrix Inc), pepsin treated bovine type I collagen, according to the manufacturer's instructions, producing a thin collagen polymer gel. Cells (2 × 106) were then seeded in 3 mL of Williams E Medium with Glutamax (Gibco), supplemented with 10% FCS. Medium was changed to 2 mL of fresh medium after 30 minutes to remove nonadherent cells and once again after 24 hours. Thirty minutes before stimulation with BMP6 (25 ng/mL; 0.69nM, final concentration) hepatocytes were pretreated with HJV.Fc (25 μg/mL; 166nM) or LDN-193189 (500nM) then 12 hours later cells were harvested and used for RNA preparation. For preparation of nuclear cell extract cells were seeded as described above and put on FCS- free medium (Williams E Medium with Glutamax; Gibco) 12 hours before stimulation. Thirty minutes before stimulation with BMP6 (25 ng/mL; 0.69nM) hepatocytes were pretreated with HJV.Fc (25 μg/mL; 166nM) or LDN-193189 (500nM) and 30 minutes later cells were harvested and used for nuclear cell extract preparation.

RNA preparation from tissue, reverse transcription and TaqMan real-time PCR

Total RNA was prepared from freshly isolated rat tissues. Four micrograms of RNA were used for reverse transcription and subsequent TaqMan real time PCR for the gene of interest as previously described.40

The following TaqMan PCR primers and probes were used: Rat hepcidin: 5′- TGAGCAGCGGTGCCTATCT -3′, 5′-CCATGCCAAGGCTGCAG-3′, FAM-CGGCAACAGACGAGACAGACTACGGC-BHQ1 Rat Gusb (β-glucoronidase): 5′-ATTACTCGAACAATCGGTTGCA-3′, 5′-GACCGGCATGTCCAAGGTT-3′, FAM-CGTAGCGGCTGCCGGTACCACT-BHQ1.

Western blotting

Cytosolic protein extracts were prepared from freshly isolated tissue and Western blotting was performed as previously described.41 Anti-ferritin antibody (2 μg/mL; Dako), anti–rat ferroportin antibody41 or anti-actin (2 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) were used as described.40

Nuclear extracts were prepared from freshly isolated tissue using a commercially available kit (NE-PER, Thermo scientific). Western blotting was performed as previously described for cellular extracts.42 Stat3-antibody (final concentration 0.1 μg/mL), phospho-Stat3(Ser727)–antibody (0.1 μg/mL), phospho-Smad1/Smad5/Smad8-antibody (0.1 μg/mL; all 3 from Cell Signaling Technology Inc), Smad1-antibody (0.1 μg/mL from Acris Antibodies) and TATA binding protein (1TBP18; final concentration 0.1 μg/mL from Abcam) were used as described.42

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS Version 17.1 software package (SPSS Inc). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to test for normality distribution. Calculations for statistical differences between various groups were carried out by ANOVA technique and Bonferroni correction for multiple tests. Otherwise, a 2-tailed Student t test with P < .05 was used to determine statistical significance of parametric data.

Results

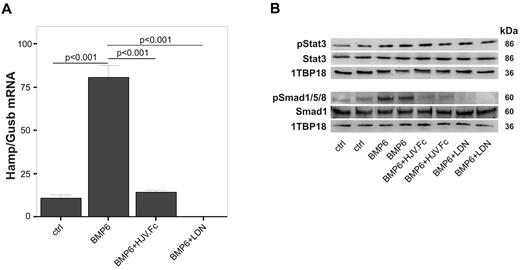

LDN-193189 and HJV.Fc block both BMP6-mediated Hamp mRNA induction and Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation in primary rat hepatocytes in vitro

To study the effects of the small molecule BMP inhibitor LDN-19318943 and the biologic BMP inhibitor HJV.Fc28 on Hamp mRNA expression in rats, we first examined their effects on primary rat hepatocytes in vitro. Addition of BMP6 (25 ng/mL) to cells resulted in significantly increased Hamp mRNA expression (Figure 1A; P < .001) compared with vehicle-treated controls. The stimulating effect of BMP6 on Hamp mRNA expression was completely blocked by preincubation of cells with LDN-193189 (500nM; P < .001) or HJV.Fc (25 μg/mL, Figure 1A; P < .001). LDN-193189 and HJV.Fc also reduced BMP6 induced Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation in primary rat hepatocytes (Figure 1B) but did not influence Stat3 phosphorylation.

LDN-193189 and soluble hemojuvelin protein (HJV.Fc) block Smad1/5/8 signaling and inhibit Hamp mRNA expression in primary rat hepatocytes. Primary rat hepatocytes were isolated from female Lewis rats and stimulated with BMP6 (25 ng/mL; 0.69nM) for 12 hours in the presence/absence of LDN-193189 (500nM) or HJV.Fc (25 μg/mL; 166nM). (A) Quantitative RT-PCR for Hamp mRNA expression relative to the housekeeping transcript β glucuronidase (Gusb) was then carried out. (B) In parallel, Western blots investigating Smad1 levels and Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation (pSmad1/5/8) as well as Stat3 levels and phosphorylation (pStat3) were carried out. 1TBP18 was used as nuclear loading control. (A) Results are reported as means ± SEM for 3 independent experiments with n = 6 per group, and the P values are shown as determined by ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple tests. (B) One representative blot of 3 independent experiments is shown.

LDN-193189 and soluble hemojuvelin protein (HJV.Fc) block Smad1/5/8 signaling and inhibit Hamp mRNA expression in primary rat hepatocytes. Primary rat hepatocytes were isolated from female Lewis rats and stimulated with BMP6 (25 ng/mL; 0.69nM) for 12 hours in the presence/absence of LDN-193189 (500nM) or HJV.Fc (25 μg/mL; 166nM). (A) Quantitative RT-PCR for Hamp mRNA expression relative to the housekeeping transcript β glucuronidase (Gusb) was then carried out. (B) In parallel, Western blots investigating Smad1 levels and Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation (pSmad1/5/8) as well as Stat3 levels and phosphorylation (pStat3) were carried out. 1TBP18 was used as nuclear loading control. (A) Results are reported as means ± SEM for 3 independent experiments with n = 6 per group, and the P values are shown as determined by ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple tests. (B) One representative blot of 3 independent experiments is shown.

LDN-193189 and HJV.Fc administration inhibit liver Hamp mRNA expression and Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation in vivo in a rat model of ACI

Next, we investigated the effect of LDN-193189 and HJV.Fc on Hamp mRNA expression in vivo using a well-established rat model of ACI. Anemia was induced by injection of group A streptococcal peptidoglycan-polysaccharide (PG-APS) resulting in a chronic inflammatory state and persistence of inflammatory anemia for many weeks.5,44,45 Liver Hamp mRNA expression was significantly increased (P = .029) in anemic rats 7 weeks after administration of PG-APS (supplemental Figure 1A, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article), which was paralleled by increased phosphorylation of Stat3 and Smad1/5/8 in livers of ACI rats compared with control animals (supplemental Figure 1B). As seen in supplemental Figure 1C, serum iron levels were significantly decreased (P < .001) in ACI rats when compared with controls. This was mainly because of iron retention within macrophages as reflected by increased ferritin and decreased ferroportin protein expression in the spleen of ACI rats (supplemental Figure 1D). Importantly, there was a significant reduction of hemoglobin levels in ACI rats 3 weeks after administration of PG-APS compared with control rats and anemia persisted for at least another 28 days (supplemental Figure 1E).

Because rats were anemic at day 21 after PG-APS administration (supplemental Figure 1E) we used this time point to start our investigations on the biologic effects of modulators of hepcidin expression.

Therefore, 21 days after PG-APS administration we injected anemic rats with a single dose of LDN-193189, HJV.Fc protein or vehicle and examined Hamp mRNA expression, Smad1/5/8 and Stat3 phosphorylation in the liver at 6 hours and 24 hours. Three weeks after PG-APS administration, Hamp mRNA, as expected, was highly elevated in ACI rats compared with control rats (Figure 2A; P = .0013). A single injection of either LDN-193189 (Figure 2B; P < .001) or HJV.Fc (Figure 2C; P < .05) significantly reduced liver Hamp mRNA expression at 6 and 24 hours, respectively, after administration compared with ACI rats injected with vehicle. This effect was paralleled by markedly reduced Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation after LDN-193189 (Figure 2E; P = .001) and HJV.Fc (Figure 2F; P < .05) treatment compared with vehicle treated ACI rats (Figure 2D). While HJV.Fc had no effect on Stat3 phosphorylation (Figure 2I), LDN-193189 transiently increased Stat3 phosphorylation (Figure 2H; P < .05) at the 6 hours time point, an effect which was not seen with prolonged treatment (Figure 3C)

LDN-193189 and HJV.Fc both inhibit hepatic Hamp mRNA induction in vivo in a rodent model of anemia of chronic inflammation. Anemia of chronic inflammation (ACI) was induced in female Lewis rats on a single intraperitoneal injection of PG-APS as detailed in “Animals” and followed up for 3 weeks. (A-C) Hamp mRNA expression relative to the housekeeping gene β glucuronidase (Gusb), (D-F) SMAD protein expression and phosphorylation (pSMAD 1/5/8) and (G-I) Stat3 expression and phosphorylation (pStat3) (G-I) were determined in livers of control and ACI rats which were treated with either a single injection of vehicle, (B,E,H) LDN-193189 [3mg/kg] or (C,F,I) HJV.Fc (20 mg/kg), at 6 hours or 24 hours before sacrifice, respectively. (D-I) 1TBP18 was used as nuclear loading control. (D-I) One representative Western blot is shown. Original Western blots used for densitometric quantification of protein expression (D-I) are shown in supplemental Figure 2. (A-I) Results are reported as means ± SEM (n = 5 in control rats, n = 6 in all other groups). Calculations for statistical differences between the various groups were carried out by Student t test and P values are shown.

LDN-193189 and HJV.Fc both inhibit hepatic Hamp mRNA induction in vivo in a rodent model of anemia of chronic inflammation. Anemia of chronic inflammation (ACI) was induced in female Lewis rats on a single intraperitoneal injection of PG-APS as detailed in “Animals” and followed up for 3 weeks. (A-C) Hamp mRNA expression relative to the housekeeping gene β glucuronidase (Gusb), (D-F) SMAD protein expression and phosphorylation (pSMAD 1/5/8) and (G-I) Stat3 expression and phosphorylation (pStat3) (G-I) were determined in livers of control and ACI rats which were treated with either a single injection of vehicle, (B,E,H) LDN-193189 [3mg/kg] or (C,F,I) HJV.Fc (20 mg/kg), at 6 hours or 24 hours before sacrifice, respectively. (D-I) 1TBP18 was used as nuclear loading control. (D-I) One representative Western blot is shown. Original Western blots used for densitometric quantification of protein expression (D-I) are shown in supplemental Figure 2. (A-I) Results are reported as means ± SEM (n = 5 in control rats, n = 6 in all other groups). Calculations for statistical differences between the various groups were carried out by Student t test and P values are shown.

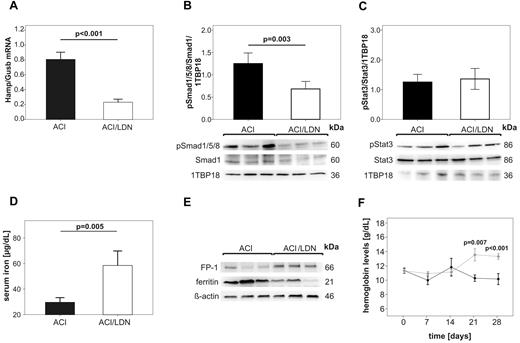

Long term treatment with LDN-193189 reverses anemia in a rodent model of ACI by modulating the hepcidin-ferroportin axis and by mobilizing iron. ACI was induced by intraperitoneal administration of PG-APS into female Lewis rats and animals were followed up for 3 weeks. Then, ACI rats were treated with either LDN-193189 (3mg/kg, ACI/LDN) or vehicle alone (ACI) by intraperitoneal administration every second day over 28 days as detailed in “Animals.” Rats were then killed and analyzed for (A) relative expression of Hamp/Gusb mRNA in the liver as determined by quantitative real-time RT-PCR, (B) hepatic Smad1 levels and Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation (pSmad1/5/8) as well as (C) Stat3 levels and Stat3 phosphorylation (pStat3) as examined by Western blot, (D) serum iron levels, and (E) the protein expression of ferroportin (FP-1) and ferritin in the spleen as visualized by Western blots. (B, C) 1TBP18 was used as nuclear loading control and (E) ß-actin as cytoplasmatic loading control. (F) Hemoglobin levels were measured in ACI rats once weekly starting with the initiation of LDN-193189 ♦ (light gray) or vehicle ● (dark) administration (day 0; 21 days after PG-APS injection). Results in panels A, B, C, D, F are reported as means ± SEM (n = 6 per group). Calculations for statistical differences between the various groups were carried out by Student t test and P values are shown. (B,C,E) One representative Western blot is shown. Western blots used for densitometric quantification (B-C) are shown in supplemental Figure 3A.

Long term treatment with LDN-193189 reverses anemia in a rodent model of ACI by modulating the hepcidin-ferroportin axis and by mobilizing iron. ACI was induced by intraperitoneal administration of PG-APS into female Lewis rats and animals were followed up for 3 weeks. Then, ACI rats were treated with either LDN-193189 (3mg/kg, ACI/LDN) or vehicle alone (ACI) by intraperitoneal administration every second day over 28 days as detailed in “Animals.” Rats were then killed and analyzed for (A) relative expression of Hamp/Gusb mRNA in the liver as determined by quantitative real-time RT-PCR, (B) hepatic Smad1 levels and Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation (pSmad1/5/8) as well as (C) Stat3 levels and Stat3 phosphorylation (pStat3) as examined by Western blot, (D) serum iron levels, and (E) the protein expression of ferroportin (FP-1) and ferritin in the spleen as visualized by Western blots. (B, C) 1TBP18 was used as nuclear loading control and (E) ß-actin as cytoplasmatic loading control. (F) Hemoglobin levels were measured in ACI rats once weekly starting with the initiation of LDN-193189 ♦ (light gray) or vehicle ● (dark) administration (day 0; 21 days after PG-APS injection). Results in panels A, B, C, D, F are reported as means ± SEM (n = 6 per group). Calculations for statistical differences between the various groups were carried out by Student t test and P values are shown. (B,C,E) One representative Western blot is shown. Western blots used for densitometric quantification (B-C) are shown in supplemental Figure 3A.

LDN-193189 and HJV.Fc administration mobilize iron and improve anemia in vivo in rats suffering from ACI

Because both LDN-193189 and HJV.Fc were able to significantly reduce Hamp mRNA expression in vivo after injection of a single dose, we proceeded to study the effect of these hepcidin lowering agents over a longer time period (4 weeks) to determine whether these agents were able to treat ACI by counteracting hepcidin-mediated iron retention within the RES. First, we treated anemic rats at 3 weeks after PG-APS administration with LDN-193189 or vehicle. Rats received intraperitoneal injections every second day for the next 4 weeks. We measured hemoglobin levels every week, and after 4 weeks, we harvested livers, spleens and sera for further analysis. LDN-193189 treatment significantly reduced liver Hamp expression (Figure 3A; P < .001) compared with ACI rats receiv-ng vehicle injections for 4 weeks. In parallel, liver Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation was markedly reduced in LDN-193189 treated ACI rats compared with ACI animals receiving vehicle injections (Figure 3B; P = .003). Of note, liver Stat3 phosphorylation was not significantly different between the LDN-193189 treated and vehicle treated groups (Figure 3C).

Interestingly, LDN-193189 treatment resulted in a significant increase of serum iron levels compared with vehicle treated controls (Figure 3D; P = .005). This increase was paralleled by elevated protein levels of the iron exporter ferroportin in the spleen and by reduced splenic levels of the iron storage protein ferritin (Figure 3E). All these changes are consistent with iron mobilization from the spleen in rats treated with LDN-193189 compared with vehicle treated rats. Most importantly, the administration of LDN-193189 resulted in a significant increase in hemoglobin levels in ACI rats, which was observed as early as 3 weeks after the start of treatment (Figure 3F; P = .007).

Although LDN-193189 efficiently blocks transcriptional activity of the BMP type I receptors ALK2 and ALK3 with greater potency and specificity than dorsomorphin,43 a recent paper has demonstrated that dorsomorphin and LDN-193189 not only inhibit BMP-mediated Smad but also p38 and Akt signaling,46 suggesting that LDN-193189 may have significant off-target effects which could potentially affect hepcidin expression.

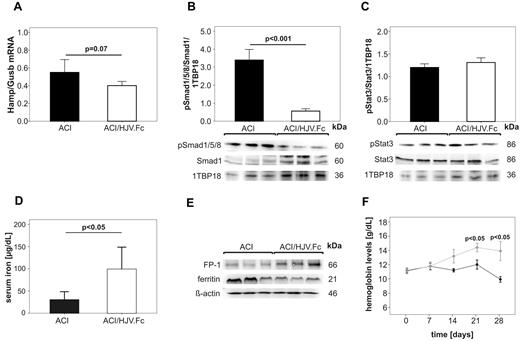

Therefore, we also tested a different type of BMP inhibitor, HJV.Fc protein, which mediates its effect through an entirely different mechanism of action to inhibit BMP signaling. HJV.Fc protein has been shown to sequester BMP ligands in a selective manner,28 and thus may be more specific in its suppression of hepcidin expression compared with LDN-193189. We induced anemia in rats with PG-APS injection and then, 3 weeks later, we began treatment with either HJV.Fc protein or vehicle by intravenous injection twice a week for an additional 4 weeks. We measured hemoglobin levels every week, and after 4 weeks we harvested livers, spleens and sera for further analysis.

At the end of the treatment period, we observed a trend toward lower Hamp mRNA levels (Figure 4A) and significantly decreased Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation (Figure 4B; P < .001) in ACI rats that received HJV.Fc protein compared with ACI rats treated with vehicle. Importantly, treatment with HJV.Fc protein significantly improved hypoferremia (Figure 4D; P < .05) that was paralleled by increased ferroportin and decreased ferritin protein levels in the spleen (Figure 4E). Strikingly, HJV.Fc protein treatment significantly increased hemoglobin levels in ACI rats as early as 21 days (P < .05) after treatment initiation compared with animals receiving vehicle control (Figure 4F).

Long term treatment with HJV.Fc reverses anemia in a rodent model of ACI by modulating the hepcidin-ferroportin axis and by mobilizing iron. ACI in female Lewis rats was induced by intraperitoneal administration of PG-APS and animals were followed up for 3 weeks. Then, ACI rats were treated with either HJV.Fc protein (20 mg/kg; ACI/HJV.Fc) or vehicle alone (ACI) by intravenous administration twice weekly over 28 days. (A) Hamp mRNA relative to Gusb mRNA expression in the liver, (B) hepatic Smad1 levels and Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation (pSmad1/5/8) as well as (C) Stat3 levels and Stat3 phosphorylation (pStat3), (D) serum iron levels and (E) the protein expression of ferroportin (FP-1) and ferritin in the spleen are shown after the termination of the experiment as detailed in the legend to Figure 3. (B-C) 1TBP18 was used as nuclear loading control and (E) β-actin as cytoplasmatic loading control. (F) Hemoglobin levels were determined in ACI rats once weekly starting with the initiation of HJV.Fc protein ♦ (light gray) or vehicle ● (dark) administration (day 0; 21 days after PG-APS injection). Results in panels A, B, C, D, F are reported as mean ± SEM, n = 10 for vehicle treated ACI rats and n = 10 for HJV.Fc treated ACI rats. Calculations for statistical differences between the various groups were carried out by Student t test. Exact P values are shown. (B,D) One representative Western blot is shown. Western blots used for densitometric quantification (B-C) are shown in supplemental Figure 3B.

Long term treatment with HJV.Fc reverses anemia in a rodent model of ACI by modulating the hepcidin-ferroportin axis and by mobilizing iron. ACI in female Lewis rats was induced by intraperitoneal administration of PG-APS and animals were followed up for 3 weeks. Then, ACI rats were treated with either HJV.Fc protein (20 mg/kg; ACI/HJV.Fc) or vehicle alone (ACI) by intravenous administration twice weekly over 28 days. (A) Hamp mRNA relative to Gusb mRNA expression in the liver, (B) hepatic Smad1 levels and Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation (pSmad1/5/8) as well as (C) Stat3 levels and Stat3 phosphorylation (pStat3), (D) serum iron levels and (E) the protein expression of ferroportin (FP-1) and ferritin in the spleen are shown after the termination of the experiment as detailed in the legend to Figure 3. (B-C) 1TBP18 was used as nuclear loading control and (E) β-actin as cytoplasmatic loading control. (F) Hemoglobin levels were determined in ACI rats once weekly starting with the initiation of HJV.Fc protein ♦ (light gray) or vehicle ● (dark) administration (day 0; 21 days after PG-APS injection). Results in panels A, B, C, D, F are reported as mean ± SEM, n = 10 for vehicle treated ACI rats and n = 10 for HJV.Fc treated ACI rats. Calculations for statistical differences between the various groups were carried out by Student t test. Exact P values are shown. (B,D) One representative Western blot is shown. Western blots used for densitometric quantification (B-C) are shown in supplemental Figure 3B.

Discussion

ACI is associated with significant morbidity and poor quality of life.1-4 Hence, correction of the anemia may improve clinical outcomes of these patients. As it is often difficult to correct the underlying disease, anemia treatment has been focused on the application of ESAs to increase hemoglobin levels. However, this approach does not address the major cause of iron dysregulation, is ineffective in a significant number of patients, and may pose a significant risk of serious cardiovascular events and death to patients suffering from ACI based on recent clinical trials.33-35 Therefore, there is a need for safer alternative strategies for the treatment of ACI.

Increased hepcidin levels in ACI are the root cause of decreased macrophage ferroportin levels and consequent iron retention in the RES, leading to an iron restricted anemia.5,47 Therefore, targeting hepcidin and reducing its effects on ferroportin might represent an effective strategy for the treatment of ACI. It has recently been reported that a combination therapy of anti-hepcidin antibody and ESA treatments can correct anemia in a murine model of anemia of inflammation. However, when used as monotherapy, neither the anti-hepcidin antibody nor the ESA were effective in correcting hemoglobin levels in this anemia model.36

We have shown in previous studies that dorsomorphin, a small-molecule inhibitor of BMP type I receptors,43 or HJV.Fc protein, a direct BMP6 antagonist,28 are each able to inhibit hepcidin formation and to mobilize iron in vitro and in vivo in rodents. We have also demonstrated that these compounds can block hepcidin induction by inflammatory cytokines in vitro,19,28 and in rodent models of Salmonella-induced and noninfectious enterocolitis in vivo.48 These data are consistent with other studies showing that an intact BMP6-Smad pathway is required for hepcidin induction by the inflammatory pathway via IL6/Stat3.22,23 We therefore speculated that these compounds would be effective in reversing anemia in ACI. We chose the PG-APS rodent model of ACI because it is the only known rodent model for a long persisting chronic anemia which resembles all the typical features of ACI in humans,44,45 in which the development of ACI is linked to increased hepcidin formation.5 In PG-APS injected rats a chronic anemia is induced within 3 weeks, which is sustained for several months. Thus, this model was ideal for us to test the hypothesis that the lowering of hepcidin will promote iron mobilization and will increase hemoglobin levels. As a result, we demonstrate that inhibiting hepcidin expression using LDN-193189, a more specific dorsomorphin analog,43 or HJV.Fc protein is effective in correcting anemia in rats.

We found decreased hepatic Hamp mRNA levels in rats suffering from ACI after treatment with HJV.Fc or LDN-193189 compared with vehicle treated ACI animals. This decrease in hepcidin levels was associated with increased ferroportin expression in the spleen, presumably from reticulo-endothelial macrophages, and with increased serum iron levels. Most importantly, we show here that mobilizing iron from the RES significantly increased hemoglobin levels after 3 weeks of treatment. The effect on hemoglobin levels was not observed in the first 2 weeks, but required 3 to 4 weeks to manifest. This time-lag is consistent with the known rate of maturation of red blood cells during erythropoiesis. Of note, the recovery of hemoglobin back to the baseline normal levels at 4 weeks with either LDN-193189 or HJV.Fc was on par if not faster than the results reported by Coccia et al45 using darpoepoietin in this same ACI model.

While this manuscript was under preparation Steinbicker and colleagues published the effects of LDN-193189 in a mouse model of acute inflammation induced anemia using repetitive turpentine injections49 which is different from the rat model used in our study which resembles chronic anemia reflecting the features of ACI. In agreement with our data presented herein, Steinbicker and colleagues also showed a partial reversion of anemia. However, we in addition present data on the molecular mechanisms underlying these observations. We include data on the effects of 2 hepcidin modulating agents, LDN-193187 and sHJV, on SMAD phoshorylation, hepcidin synthesis, ferroportin expression, body iron homeostasis and mobilization and most importantly on the successful and sustained reversal of anemia using repeated measurements over time.

Similar results were obtained using 2 different types of inhibitors of BMP signaling with 2 distinct mechanisms of action. This indicates that there is a high likelihood that the correction of anemia observed in the PG-APS rat model of ACI was not because of an off target effect of either inhibitor. Interestingly, hepatic phosphorylated Smad1/5/8 levels were increased in our ACI rat model compared with control animals. This suggests that the inhibition of the BMP/Smad pathway has directly contributed to the hepcidin-lowering effects of LDN-193189 and HJV.Fc in this ACI model.

Because blockade of iron release from the RES is the primary pathophysiologic reason for the anemia seen in ACI, logic dictates that relief of this blockade would be an effective treatment for ACI. Our results support the novel hypothesis that hepcidin lowering agents will promote the release of iron from RES stores and will be an effective treatment for ACI.

Although Stat3 phosphorylation was not altered in ACI rats receiving LDN-193189 or HJV.Fc for 4 weeks, modulation of hepcidin expression may impact on the degree of inflammation in subjects suffering from ACI, because changes of hepcidin levels as well as manipulation of iron availability have been shown to affect immune response pathways.50,51 Nonetheless, it will be of utmost importance to prospectively investigate the effects of pharmacologic iron mobilistaion and reversal of anemia on the course of the disease underlying ACI.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Austrian research funds (FWF P-19664; TRP-188, G.W.), research funds from the Medical University of Innsbruck (MFI 2007-416, I.T.) and a grant from the OENB (14182, I.T.). J.L.B. was supported by National Institutes of Health grants K08 DK075846 and RO1 DK087727, and the Satellite Dialysis Young Investigator grant from the National Kidney Foundation. H.Y.L. was supported by National Institutes of Health grants RO1 DK069533 and RO1 DK071837.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: I.T. was involved in the study design, completion of experiments, data analysis and interpretation and manuscript preparation; A.S. helped with animal experiments, performed cell culture experiments and helped with RT-PCR and Western blotting experiments, T.S. helped with animal experiments and performed cell culture experiments; M.N. helped with animal experiments; M.T. did the isolation of primary rat hepatocytes; W.W. contributed to data analysis and writing of the manuscript; K.E. helped with animal experiments and bone marrow isolation; D.W. contributed to data analysis and writing of the manuscript; M.S. helped with RT-PCR and Western blotting experiments; C.C.S. contributed to data analysis and writing of the manuscript; J.L.B. contributed to study design, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript; C.C.H was involved in the production of LDN-193189; T.M and P.G. were involved in the production of HJV.Fc; H.Y.L was involved in study design, data interpretation, and writing of the manuscript; and G.W. was involved in the design of the study and experiments, data analysis and interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. All authors have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: H.Y.L., J.L.B., T.M., P.G., and G.W. have ownership interest in start-up company Ferrumax Pharmaceuticals, which has licensed technology from the Massachusetts General Hospital. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Guenter Weiss, MD, Medical University, Department of Internal Medicine I, Clinical Immunology and Infectious Diseases, Anichstr 35, A 6020 Innsbruck, Austria; e-mail: guenter.weiss@i-med.ac.at; or Herbert Y. Lin, MD, PhD, Massachusetts General Hospital, 185 Cambridge St, CPZN-8216, Boston, MA 02114; e-mail: lin.herbert@mgh.harvard.edu.

![Figure 2. LDN-193189 and HJV.Fc both inhibit hepatic Hamp mRNA induction in vivo in a rodent model of anemia of chronic inflammation. Anemia of chronic inflammation (ACI) was induced in female Lewis rats on a single intraperitoneal injection of PG-APS as detailed in “Animals” and followed up for 3 weeks. (A-C) Hamp mRNA expression relative to the housekeeping gene β glucuronidase (Gusb), (D-F) SMAD protein expression and phosphorylation (pSMAD 1/5/8) and (G-I) Stat3 expression and phosphorylation (pStat3) (G-I) were determined in livers of control and ACI rats which were treated with either a single injection of vehicle, (B,E,H) LDN-193189 [3mg/kg] or (C,F,I) HJV.Fc (20 mg/kg), at 6 hours or 24 hours before sacrifice, respectively. (D-I) 1TBP18 was used as nuclear loading control. (D-I) One representative Western blot is shown. Original Western blots used for densitometric quantification of protein expression (D-I) are shown in supplemental Figure 2. (A-I) Results are reported as means ± SEM (n = 5 in control rats, n = 6 in all other groups). Calculations for statistical differences between the various groups were carried out by Student t test and P values are shown.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/118/18/10.1182_blood-2011-03-345066/4/m_zh89991177120002.jpeg?Expires=1767708921&Signature=JV2pqdQ0tBjaNCbX8NxkkxUuM5mSFy28~MNG6hlBkpgzDysJztWOnAH6tN6vflugxnQ8cy-CTcsOa9uQJdTWRv~J1RADKfhvz27devQ4o~64zJUCSgu70y3-oEnTJ6F4ll1wuJz2vGolkMA5QuQoRm641Yyd3PrSzk7tvTwt63aN86DZBBFyao8oW4eSkv73Of52bNeyTE-KxStwnGJDAL~htLTshPyoaAw4s0O3CwMUnzwzL0ebELIfwyKqUKvCfRdozNQT0N24iRRmVz-vad8Z-1JlzDqFFLWNtUmsfZy7ivlYddwh8VF-zAeJkHizQdFYFmUJPilPjRUUyucUMw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal