Abstract

Chromatin insulators protect erythroid genes from being silenced during erythropoiesis, and the disruption of barrier insulator function in erythroid membrane gene loci results in mild or severe anemia. We showed previously that the USF1/2-bound 5′HS4 insulator mediates chromatin barrier activity in the erythroid-specific chicken β-globin locus. It is currently not known how insulators establish such a barrier. To understand the function of USF1, we purified USF1-associated protein complexes and found that USF1 forms a multiprotein complex with hSET1 and NURF, thus exhibiting histone H3K4 methyltransferase- and ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling activities, respectively. Both SET1 and NURF are recruited to the 5′HS4 insulator by USF1 to retain the active chromatin structure in erythrocytes. Knock-down of NURF resulted in a rapid loss of barrier activity accompanied by an alteration of nucleosome positioning, increased occupancy of the nucleosome-free linker region at the insulator site, and increased repressive H3K27me3 levels in the vicinity of the HS4 insulator. Furthermore, suppression of SET1 reduced barrier activity, decreased H3K4me2 and acH3K9/K14, and diminished the recruitment of BPTF at several erythroid-specific barrier insulator sites. Therefore, our data reveal a synergistic role of hSET1 and NURF in regulating the USF-bound barrier insulator to prevent erythroid genes from encroachment of heterochromatin.

Introduction

Erythropoiesis involves commitment and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells into mature erythrocytes and is associated with progressively increasing chromatin condensation during differentiation until enucleation occurs. Erythrocytes represent a very specialized cell type in which the majority of the genome is silenced but a small number of genes, many of them erythroid specific such as the α- and β-globin genes, continue to be expressed.1 How these genes escape heterochromatization and gene silencing is poorly understood.

In eukaryotic nuclei, euchromatin domains consist of irregularly spaced hyperacetylated and H3K4 methylated nucleosomes. In contrast, heterochromatin is organized by regular, short interval positioning of nucleosomes enriched with methylated H3K9 and H3K27, hypoacetylated histone tails, and binding of heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1).2 The structure of chromatin is maintained by the actions of histone-modifying enzymes and chromatin remodeling complexes. In the absence of constraints, the spread of heterochromatin formation into euchromatin regions causes position-effect variegation, a stable and heritable epigenetic silencing of a euchromatin gene.3 Barrier elements prevent the extension of heterochromatin formation.4 Although organisms have evolved different ways to block the spread of heterochromatin, recent studies point to a common mechanism by which barriers recruit and establish euchromatin-specific histone modifications at the boundary.

Barrier elements regulate developmental cell- and tissue type–specific expression, making them critical for the normal growth, development, and differentiation of all cell types. Recent studies carried out on a barrier element in the ankyrin-1 gene associated with hereditary spherocytosis5 have indicated that mutation of the DNA-binding component of a barrier insulator can also perturb gene expression and result in an inherited disease phenotype. Despite the importance to inherited and acquired genetic disease, the structure and function of vertebrate barrier elements are poorly understood. Most of our understanding comes from study of the chicken cHS4 barrier element from the β-globin locus.

The cHS4 insulator at the 5′ end of the chicken β-globin locus lies immediately downstream of an ∼16-kb condensed chromatin and acts as a barrier to protect the active globin domain from being silenced in mature erythrocytes.6,7 In avian erythroid cells, the nucleosomes surrounding the 5′HS4 insulator are highly enriched with active histone modifications regardless of whether the neighboring genes are transcribed.8-10 The barrier activity of the 5′HS4 insulator is mediated in part by the binding of USF1 and USF2. USF1 recruits many modifying enzymes and establishes a peak of euchromatin-specific histone modifications at the 5′HS4 insulator site in the globin locus.11,12 Deletion of the USF-binding site at 5′HS4 or disruption of the USF DNA–binding activity not only eliminates the recruitment of histone-modifying enzymes but also abolishes barrier activity.11,12 USF also mediates the barrier insulator activity in the human erythroid-specific α-spectrin gene13 and in the human ankyrin-1 loci.5 The association of USF proteins with these recently identified chromatin barriers in erythroid-specific gene loci supports the idea that USF mediates active histone modifications of barrier-associated nucleosomes that block the spread of heterochromatin. USF1 interacts with the lysine methyltransferase SET7/9,11 but SET7/9 is exclusively a monomethylase14,15 and may not be responsible for the H3K4 di- and trimethylation peaks seen in the 5′HS4 insulator of the chicken β-globin locus.

To understand how USF1 contributes to chromatin barrier function in erythroid cells, we isolated and characterized USF1-associated protein complexes. In addition to an ∼ 300-670 kDa complex that contains HATs and PRMT1,12 we have identified a 1.8 MDa complex in which USF1 associates with the H3K4 methyltransferase hSET1 and the human nucleosome remodeling factor (NURF) complexes. The SET1 and the NURF complexes colocalize with USF1 at the endogenous barrier insulator sites in the chicken β-globin and human α-spectrin gene loci. Knock-down of SET1 resulted in a rapid loss of barrier activity accompanied by a significant decrease of H3K4me2 and a strong loss of NURF recruitment. In contrast, depletion of SET1 increased repressive H3K27me3 and H3K9me2 marks at the barrier insulator elements at ectopic transgene sites, as well as in the endogenous chicken β-globin and human α-spectrin loci. Knock-down of BPTF also led to a rapid loss of barrier function that was accompanied by repositioned, tightly packed nucleosomes at the 5′HS4 site of the chicken β-globin locus. Our data reveal that hSET1 and NURF cooperate to regulate chromatin barrier activity and likely contribute to the maintenance of erythroid-specific transcription programs during erythropoiesis.

Methods

Cell lines and shRNA-mediated knock-down (KD)

Chicken 6C2 erythroleukemia cells carrying the IL2R reporter transgenes (without insulator, clone 9; with insulator, clone 809) were cultured as described previously.6,16 Constructs used for shRNA expression were generated by subcloning shRNA oligonucleotides into the pSuper.retro.puro vector following the manufacturer's instructions (Oligoengine). Retrovirus generation and infections were performed as described previously.17

Primary erythroid cell culture and selection

Human CD34-selected stem and progenitor cells were cultured in StemSpan SF expansion medium (09650; StemSpan) with estradiol (100 ng/mL), dexamethasone (10 ng/mL), human transferrin (200 ng/mL), insulin (10 ng/mL), Flt3 ligand (100 ng/mL), SCF (100 ng/mL), IL3 (50 ng/mL), IL6 (20 ng/mL), insulin like growth factor-1 (50 ng/mL), and erythropoietin (3 U/mL) for 9-14 days.18,19 FACS analysis was used to isolate cells expressing CD71 (transferrin receptor) and CD235a (glycophorin A), defined as the R3/R4 population of differentiating erythroid cells.20

Barrier analysis

Barrier assays were performed as described previously.6 Cells (5 × 105) from single-copy integrant clones were collected and stained with FITC-conjugated anti–human CD25 (IL2R) antibody (eBioscience) and analyzed on a flow cytometer. FACS was performed at the indicated time points in the absence of selection.

Purification of USF1 complexes and histone methyltransferase assay

Purification of the USF1 containing complex was performed in HeLa S3 cells stably transduced with a FLAG-hemagglutinin (HA)–tagged chicken USF1, as described previously.12 The eluted USF1 complexes were incubated with histone H3 or H3K4me3 tails in a HMT buffer in the presence of 1 μL of [3H]S-adenosylmethionine (15 Ci/mmol; PerkinElmer) at 30°C for 1 hour.

Nucleosome-sliding assays

Nucleosome-remodeling assays were performed essentially as described previously.21 Briefly, the purified core histones from HeLa cells were incubated with a 194-bp DNA fragment comprising a strong nucleosome positioning sequence from the pGEM-3Z-601 clone22 to reconstitute mononucleosome in high salt conditions. The reconstituted mononucleosome was incubated with the NURF or the USF1 complex in the presence or absence of ATP. Mononucleosomes were resolved on a native 6% PAGE.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis

Immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis were carried out as described previously.23 Anti-USF1 (H-86) antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-hSET1 (A300-289A, A300-290A), anti-RbBP5 (A300-109A), anti-ASH2L (A300-489A), and anti-HCF1 (A301-399A) antibodies were from Bethyl Laboratories. Anti-SNF2 and anti-PAF1 antibodies were from Millipore. Anti-BPTF antiserum was generated in rabbits using a chicken BPTF fragment (aa 2775-2789) as an antigen.

ChIP analysis

Native ChIP assays for histone modifications were performed in the absence of formaldehyde cross-linking, as described previously,8 using antibodies specific to various histone modifications: anti-H3K9K14ac (06-599), anti-H3K4me2 (07-030), anti-H3K9me2 (07-212), and anti-H3K27me3 (07-449) from Upstate Biotechnology. ChIP analysis of transcription factor binding was performed using cross-linked chromatin. The ChIP primers have been described previously.8,10,11

Nucleosome mapping assay

The nucleosome scanning assay was performed as described previously.24 Briefly, the mononucleosomal DNA was analyzed by a set of overlapping primer pairs covering the 5′HS4 insulator region by real-time quantitative PCR. The relative nucleosomal DNA enrichment level of a given DNA region was calculated as 2Ct(gDNA) − Ct(mono), where Ct(gDNA) is the threshold amplification level of genomic DNA and Ct(mono) is the threshold amplification level of mononucleosomal DNA.

Results

USF1 associates with hSET1 and NURF complexes

We have shown previously that USF1 and USF2 interact with footprint IV (FIV) and that the binding of USF proteins is essential for the establishment and maintenance of positive histone modifications and barrier activity at this site.11,12 To further understand the role of USF1 in histone modification and barrier formation, we purified USF1-containing protein complexes from Flag/HA–tagged USF1-expressing HeLa cells through immuno-affinity purification (Figure 1A). In addition to the PRMT1 and HAT complexes reported previously,12 the list of USF1-interacting polypeptides identified contained multiple components of the hSET1 and NURF complexes (Figure 1A). Similar interactions occur in erythroid cells, both USF1 and hSET1 antibodies were able to efficiently precipitate the components of hSET1 and NURF complexes in K562 human erythroleukemia cells (Figure 1B). In addition, the interaction between USF1 and the SET1 complex was confirmed in murine erythroleukemia cells and chicken 6C2 cells (supplemental Figure 1G-H, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). To analyze whether hSET1 and NURF complexes coexisted in the same complex with USF1, Flag-USF1 containing HeLa nuclear extract was fractionated through a Sephacryl S-300 HR column (Amersham Bioscience). Each fraction was collected and analyzed by Western blot using antibodies specific to USF1 and its associated proteins. USF1 comigrated with components of the hSET1 complex consistent with an ∼ 1.8 MDa size (supplemental Figure 1A-F). To determine whether NURF was present in the 1.8 MDa complex, the peak fractions corresponding to the size of 1.8 MDa (I), 300-650 kDa (II), and < 50 kDa (III) were collected separately, precipitated with anti-Flag antibody, and analyzed for the presence of hSET1 and NURF components (Figure 1C). hSET1 and NURF components were only present with USF1 in the 1.8 MDa peak fractions (Figure 1C), which is consistent with an association of USF1 with hSET1 and NURF as part of the same complex in mammalian cells. To further confirm the size of the USF1/hSET1/NURF complex, the purified USF1 complexes were also fractionated through a Superose-6 sizing column and analyzed by Western blotting (supplemental Figure 2A-B); again, USF1, hSET1, and NURF formed a complex of 1.8 MDa (supplemental Figure 2A-B).

USF1 associates with H3K4 methyltransferase hSET1- and nucleosome-remodeling NURF complexes. (A) Partial list of USF1-associated polypeptides identified by LC-MS/MS is shown. (B) Endogenous USF1 associates with hSET1 and NURF complexes in erythroid cells. Nuclear extracts from K562 cells were immunoprecipitated with USF1 and hSET1 antibodies and analyzed by Western blotting. (C) Nuclear extracts from HeLa cells expressing Flag-USF1 were fractionated through a Sephacryl S-300 HR column. The peak fractions from the 1.8-MDa complex (I) corresponding to hSET1, the 300 to 670-kDa complex (II) corresponding to PRMT1 and HATs, and the < 50-kDa complex (III) were collected, respectively. The pooled fractions were immunoprecipitated with Flag antibody. The precipitates were then analyzed by Western blot analysis using antibodies against hSET1, ASH2L, RBBP5, BPTF, and SNF2. (D) USF1 associates with H3K4-specific methyltransferase activity. The purified USF1-associated complexes were incubated with histone H3 peptide or H3K4me3 peptide in the presence of [3H]AdoMet as a cofactor. The proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by fluorography. (E) ATP-dependent nucleosome sliding by the USF1-associated protein complex. A 194-bp DNA fragment containing a strong nucleosome positioning sequence was PCR amplified and assembled with purified HeLa core histones. The nucleosome sliding reactions were carried out with increasing amounts of the purified USF1-associated complexes in the presence or absence of ATP. Mobilized mononucleosomes were analyzed on a native 6% polyacrylamide gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The purified recombinant Drosophila NURF complex was used as a positive control.

USF1 associates with H3K4 methyltransferase hSET1- and nucleosome-remodeling NURF complexes. (A) Partial list of USF1-associated polypeptides identified by LC-MS/MS is shown. (B) Endogenous USF1 associates with hSET1 and NURF complexes in erythroid cells. Nuclear extracts from K562 cells were immunoprecipitated with USF1 and hSET1 antibodies and analyzed by Western blotting. (C) Nuclear extracts from HeLa cells expressing Flag-USF1 were fractionated through a Sephacryl S-300 HR column. The peak fractions from the 1.8-MDa complex (I) corresponding to hSET1, the 300 to 670-kDa complex (II) corresponding to PRMT1 and HATs, and the < 50-kDa complex (III) were collected, respectively. The pooled fractions were immunoprecipitated with Flag antibody. The precipitates were then analyzed by Western blot analysis using antibodies against hSET1, ASH2L, RBBP5, BPTF, and SNF2. (D) USF1 associates with H3K4-specific methyltransferase activity. The purified USF1-associated complexes were incubated with histone H3 peptide or H3K4me3 peptide in the presence of [3H]AdoMet as a cofactor. The proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by fluorography. (E) ATP-dependent nucleosome sliding by the USF1-associated protein complex. A 194-bp DNA fragment containing a strong nucleosome positioning sequence was PCR amplified and assembled with purified HeLa core histones. The nucleosome sliding reactions were carried out with increasing amounts of the purified USF1-associated complexes in the presence or absence of ATP. Mobilized mononucleosomes were analyzed on a native 6% polyacrylamide gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The purified recombinant Drosophila NURF complex was used as a positive control.

USF1 complexes exhibit hSET1 and NURF enzymatic activities

hSET1 complexes are responsible for mono-, di-, and trimethylation of lysine 4 of histone H3. NURF complexes help to facilitate nucleosome remodeling in an ATP-dependent manner. We analyzed whether the purified USF1 protein complexes exhibit H3K4 methyltransferase and nucleosome remodeling activities. The USF1-containing complex strongly methylated unmodified histone H3 tails, whereas a mock-purified fraction failed to do so (Figure 1D compare lanes 1 and 2). The methyltransferase activity was completely abolished when the H3 substrate was trimethylated at the Lys4 residue (Figure 1D lane 3). We conclude that USF1 associates with a functional hSET1 complex possessing H3K4 methyltransferase activity.

NURF catalyzes nucleosome sliding in an ATP-dependent fashion.25 We investigated whether the purified USF1 complex possesses remodeling activity on a reconstituted mononucleosome positioned at the end of a 194-bp-strong nucleosome positioning DNA sequence. As has been shown previously,26 the NURF complex moved the terminally positioned nucleosome 10 bp each step toward the center of the fragment with characteristic N2 and N3 positions in the presence of ATP (Figure 1E lane 6). The purified USF1 complex also efficiently moved the mononucleosome from the N1 position to the centrally located N2 and N3 positions and reduced nucleosome occupancy at the N1 position in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1E compare lanes 7 and 8 with lane 3). In addition, the reaction was ATP dependent, because neither the NURF nor the USF1 complexes exhibited remodeling activity in the absence of ATP (Figure 1E lanes 4 and 5). Therefore, our data demonstrate that the purified USF1 complex exhibits ATP-dependent NURF-associated nucleosome remodeling activity.

SET1 and NURF are associated with the endogenous 5′HS4 insulator in vivo

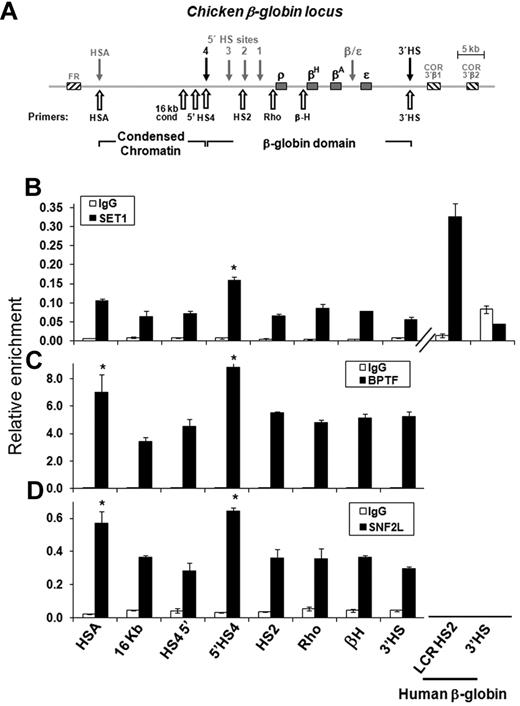

To investigate the co-occupancy of SET1 and NURF complexes at the 5′HS4 insulator site, we carried out ChIP assays across the entire chicken β-globin locus in 6C2 cells (Figure 2A). The antigen epitopes for hSET1 and BPTF were identical among human, mouse, and chicken. They recognized endogenous chicken proteins by Western blotting analysis (supplemental Figure 1H, Figure 3C, and supplemental Figure 3D). SET1, ASH2L, RBBP5, SNF2L, and BPTF were enriched at the cHS4 insulator site of the chicken β-globin locus (Figure 2 and supplemental Figure 3B-C). Although slight enrichment for SET1 was observed at the folate receptor HSA enhancer, there was no enrichment observed in the 16-kb condensed chromatin region (Figure 2B). The degree of SET1 enrichment at the HS4 compared with the 16-kb region in 6C2 cells is smaller than that of the HS2 compared with the 3′HS of the human β-globin locus in K562 cells, but significantly higher than the negative regions (Figure 2B). However, we noticed a significant enrichment of components of the NURF complex, BPTF and SNF2L, in the folate receptor HSA region (Figure 2C-D). NURF is associated with transcriptionally active promoters and the folate receptor gene is actively transcribed in 6C2 cells.10 ASH2L and RBBP5 were enriched at the HSA, HS4, and the LCR of the chicken β-globin gene locus (supplemental Figure 3). These regions were also enriched for H3K4me2 in 6C2 cells.9 In contrast, there was no enrichment for the IgG control over the chicken β-globin locus (Figure 2). It is possible that these regions may recruit other HMTs such as MLL, which share structural subunits such as ASH2L and RBBP5 with the SET1 complex. These data demonstrate that SET1 and NURF are recruited to the endogenous 5′HS4 insulator, likely through interactions with USF1.

SET1 and NURF complexes interact with the 5′HS4 insulator in vivo. ChIP analysis in chicken erythroid progenitor 6C2 cells. (A) Schematic representation of the chicken β-globin cluster is shown. Open arrows indicate locations of primer sets used in ChIP analysis. ChIP analysis of SET1 (B), BPTF (C), and SNF2L (D) compared with IgG. Comparison of hSET1 enrichments at the human β-globin HS2 and the negative control region 3′HS, as well as at the chicken β-globin locus HSA and HS4 and the negative control region 16 kb and 3′HS (B). *P < .01 by Student t test. Shown are the means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments.

SET1 and NURF complexes interact with the 5′HS4 insulator in vivo. ChIP analysis in chicken erythroid progenitor 6C2 cells. (A) Schematic representation of the chicken β-globin cluster is shown. Open arrows indicate locations of primer sets used in ChIP analysis. ChIP analysis of SET1 (B), BPTF (C), and SNF2L (D) compared with IgG. Comparison of hSET1 enrichments at the human β-globin HS2 and the negative control region 3′HS, as well as at the chicken β-globin locus HSA and HS4 and the negative control region 16 kb and 3′HS (B). *P < .01 by Student t test. Shown are the means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments.

SET1 and NURF are responsible for chromatin barrier activity

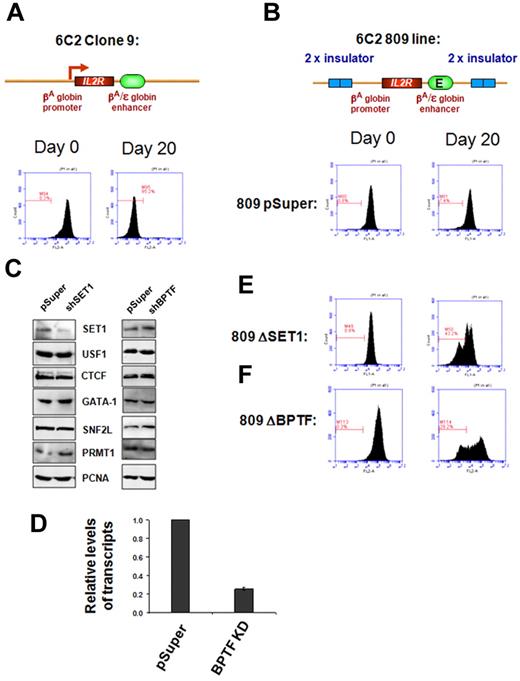

USF1 is required for H3K4 methylation and barrier activity at the 5′HS4 insulator element in chicken erythroleukemia cells.11,12 It is conceivable that recruitment of SET1 or NURF by USF1 might be responsible for barrier activity. To test this hypothesis directly, we performed a chromatin barrier assay in the chicken erythroid 6C2 line 809. This line contains 4 copies of the stably integrated human IL2R reporter gene driven by the chicken βA-globin promoter and the β/ϵ enhancer, which is flanked by 2 copies of the chicken 5′HS4 insulator (Figure 3).16 The 5′HS4 protected IL2R reporter construct continuously expressed the IL2R gene after withdrawal of hygromycin selection (Figure 3B), whereas the uninsulated IL2R reporter line clone 9 was rapidly silenced (Figure 3A), indicating that the cHS4 barrier is essential to block heterochromatin spreading into the expression cassette.6,16

SET1 and NURF complexes are responsible for chromatin barrier activity of the 5′HS4 insulator. FACS analysis of transgenic IL2R expression. (A) Clone 9 cells contain 13 copies of the human IL2R reporter transgene driven by the chicken βA-globin promoter and the β/ϵ enhancer and integrated stably into the genome of the chicken erythroid 6C2 cell line. After withdrawal of hygromycin selection, the transgenes became transcriptionally silent in 20 days. (B) The 809 cells contain 4 copies of the IL2R transgenes flanked by the 5′HS4 insulators, and expression of IL2R is maintained in this fully insulated line culture (809-pSuper). (C) Western blot analysis of endogenous nonerythroid or erythroid specific proteins in 6C2 809 cells harboring vector control and shSET1 (left) or shBPTF (right). The SET1 KD clone shows a significant reduction of the SET1 protein but not broadly expressed transcription factors or the erythroid-specific transcription factor GATA-1. (D) Quantitative RT-PCR of BPTF mRNA levels isolated from vector control–transfected and shBPTF-transfected cells. In 809 cells, depletion of SET1 (E) or BPTF (F) resulted in a rapid loss of chromatin barrier activity, as indicated by transcription silencing of the transgenic IL2R due to chromosomal position effect silencing. The gated bar designates IL2R-negative cells. Results from 10 000 cells are shown. The y-axis is the number of cells and the x-axis is the fluorescence intensity.

SET1 and NURF complexes are responsible for chromatin barrier activity of the 5′HS4 insulator. FACS analysis of transgenic IL2R expression. (A) Clone 9 cells contain 13 copies of the human IL2R reporter transgene driven by the chicken βA-globin promoter and the β/ϵ enhancer and integrated stably into the genome of the chicken erythroid 6C2 cell line. After withdrawal of hygromycin selection, the transgenes became transcriptionally silent in 20 days. (B) The 809 cells contain 4 copies of the IL2R transgenes flanked by the 5′HS4 insulators, and expression of IL2R is maintained in this fully insulated line culture (809-pSuper). (C) Western blot analysis of endogenous nonerythroid or erythroid specific proteins in 6C2 809 cells harboring vector control and shSET1 (left) or shBPTF (right). The SET1 KD clone shows a significant reduction of the SET1 protein but not broadly expressed transcription factors or the erythroid-specific transcription factor GATA-1. (D) Quantitative RT-PCR of BPTF mRNA levels isolated from vector control–transfected and shBPTF-transfected cells. In 809 cells, depletion of SET1 (E) or BPTF (F) resulted in a rapid loss of chromatin barrier activity, as indicated by transcription silencing of the transgenic IL2R due to chromosomal position effect silencing. The gated bar designates IL2R-negative cells. Results from 10 000 cells are shown. The y-axis is the number of cells and the x-axis is the fluorescence intensity.

We then investigated whether SET1 or NURF are required for barrier activity in the assay described above using shRNA-mediated KD of SET1 or BPTF in the 6C2 line 809. Two of these lines displayed a marked reduction in SET1 protein levels (Figure 3C) and 2 lines showed 60%-75% reduction in BPTF mRNA levels compared with the 809 pSuper vector control (Figure 3D and supplemental Figure 4E). Knockdown did not affect the expression of ubiquitous or erythroid-specific factors such as USF1, CTCF, SNF2L, PRMT1, and GATA-1, which regulate insulator function or erythropoiesis (Figure 3C). Compared with cells transfected with the 809 pSuper control, which uniformly and continuously expressed the IL2R reporter for 20 days upon withdrawal of hygromycin selection (Figure 3B and supplemental Figure 4C), depletion of SET1 led to a marked and rapid decrease in IL2R expression (overall intensity) by 43.2% at day 20 (Figure 3E), which was similar to the decreased expression in the uninsulated IL2R reporter 6C2 line clone 9 (Figure 3A). The second SET1 KD clone was also rapidly silenced (data not shown). Interestingly, inhibition of BPTF, a component of the ATP-dependent NURF complex, also resulted in a strong reduction (29%-62%) in IL2R expression levels (Figure 3F and supplemental Figure 4D). These data demonstrate that the recruitment of the SET1 and BPTF complexes, perhaps by USF1, to the HS4 insulator is necessary for barrier activity.

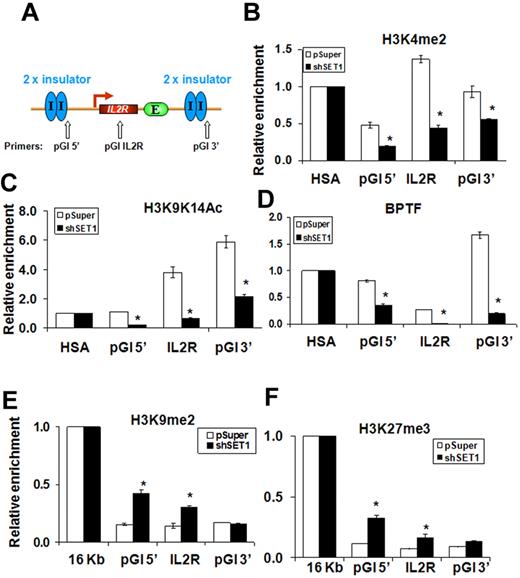

The role of the SET1 complex in chromatin barrier activity

Euchromatin-specific histone modifications such as H3K4me2 have been proposed to function as “terminator” marks that counteract the spreading of H3K9-methylated condensed chromatin, a conserved mechanism proposed for barrier insulators ranging from those in yeast to those in humans.3 Suppression of H3K4 methyltransferase activity may eliminate the terminator. The silencing of the IL2R transgene in SET1 KD 6C2 erythroid cells may therefore result from a rapid loss of the H3K4me2 mark and barrier at the 5′HS4 insulator. We therefore examined the histone acetylation and methylation patterns over the 809 6C2 clone transduced with retroviruses harboring pSuper vector or SET1 shRNA (Figure 3C). Depletion of SET1 led to drastically decreased H3K4me2 and AcH3K9/K14, indicating that SET1 is responsible for establishing the H3K4 methylation marks at the transgenic locus (Figure 4B-C). We observed a 60% decrease at the 5′cHS4 flanking site, a 65% reduction at the IL2R transgene, and a 40% decrease of H3K4me2 at the 3′cHS4 flanking site in the SET1 KD clone (Figure 4A-B). H3 acetylation was also dramatically reduced at the cHS4 flanking sites and in the IL2R transgene (Figure 4C). Interestingly, the recruitment of BPTF to the flanking cHS4 insulator sites was diminished in the SET1 KD line (Figure 4D), suggesting that localization of the NURF complex at the insulator may be dependent on SET1-mediated H3K4 methylation (see “Discussion”). We next examined the repressive H3K9me2 and H3K27me3 marks over the integrated transgene. H3K9me2 was markedly increased at the flanking insulator sites in the SET1 KD clone (Figure 4E): 2.7- and 2.2-fold at the 5′insulated site and the IL2R transgene, respectively (Figure 4E). H3K27me3 was also elevated over the entire IL2R transgenic locus (Figure 4F). As a control, KD of SET1 affected neither the expression of general factors nor the erythroid-specific transcription factor GATA-1 in 6C2 erythroid progenitors (Figure 3C), suggesting that the SET1 KD likely affected chromatin barrier activity directly. However, SET1 KD cells grew slowly and differed morphologically from wild-type erythroid cells (see “Discussion”). In summary, we identified the SET1 complex as being responsible for the establishment and maintenance of active histone modifications and boundary function at the 5′HS4 insulator.

The SET1 complex is responsible for maintaining H3K4 methylation and other active modifications to protect the 5′HS4-insulated transgene. (A) Schematic representation of the insulated IL2R transgene, which contains 4 copies, in the 6C2 genome (line 809), and the position of PCR primer sets used in ChIP analysis. (B-F) ChIP analysis of the flanking 5′HS4 sites and the integrated IL2R transgenes comparing the pSuper control infected and SET1 KD 809 cells. The relative enrichment of precipitated DNA fragments using antibodies specific to H3K4me2 (B), H3K9K14ac (C), BPTF (D), H3K9 dimethylation (E), and H3K27me3 (F) were normalized to enrichment of the endogenous HSA or 16-kb condensed chromatin fragments to adjust for immunoprecipitation efficiency. *P < .01 by Student t test. Shown are the means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments.

The SET1 complex is responsible for maintaining H3K4 methylation and other active modifications to protect the 5′HS4-insulated transgene. (A) Schematic representation of the insulated IL2R transgene, which contains 4 copies, in the 6C2 genome (line 809), and the position of PCR primer sets used in ChIP analysis. (B-F) ChIP analysis of the flanking 5′HS4 sites and the integrated IL2R transgenes comparing the pSuper control infected and SET1 KD 809 cells. The relative enrichment of precipitated DNA fragments using antibodies specific to H3K4me2 (B), H3K9K14ac (C), BPTF (D), H3K9 dimethylation (E), and H3K27me3 (F) were normalized to enrichment of the endogenous HSA or 16-kb condensed chromatin fragments to adjust for immunoprecipitation efficiency. *P < .01 by Student t test. Shown are the means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments.

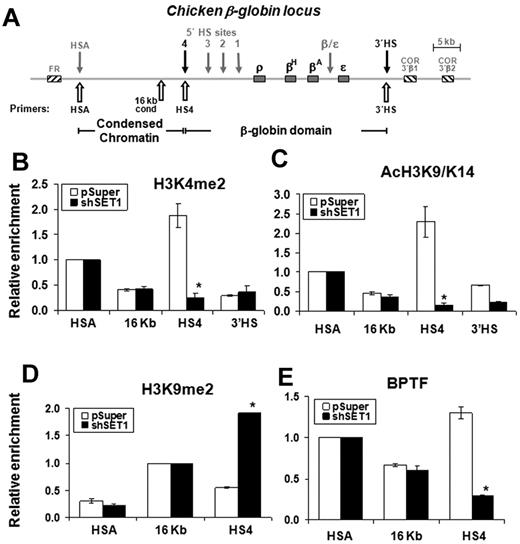

In the endogenous chicken β-globin locus, the cHS4 insulator is located at the 5′end of the globin domain and is situated immediately downstream of a 16-kb condensed heterochromatin region (Figure 5A). USF1 is a critical component of the cHS4 insulator, which establishes and maintains active histone modifications to protect downstream globin genes.11 Knock-down of SET1 led to a dramatic loss of H3K4 methylation and H3 acetylation at some sites in this region. In the SET1 KD 6C2 cells, H3K4me2 was reduced by 85% at the 5′HS4 insulator site but not in the 16-kb upstream regions or at the 3′HS sites of the chicken β-globin locus (Figure 5B). A similar pattern was also observed for H3 acetylation (Figure 5C). H3K9me2 spreads across the 5′HS4 insulator into the open globin domain upon the loss of barrier activity,11 and the levels were elevated by 3.5-fold at the cHS4 insulator site (Figure 5D). Furthermore, the recruitment of BPTF at the cHS4 site was essentially lost in the SET1 KD cells (Figure 5E). The fragments precipitated with control IgG were not enriched for the ectopic and endogenous HS4 insulator sites (supplemental Figure 5). The role of SET1 in barrier activity is consistent with the notion that USF1 binding to the insulator is critical for the establishment and maintenance of active H3K4 methylation. Although NURF and SET1 may both be bound to USF1 and recruited to the insulator site, stable recruitment of NURF depends on the methylation status of histone H3, suggesting a possible coordination of these 2 complexes in barrier function.

The SET1 complex is required for maintaining H3K4 methylation and recruitment of the NURF complex at the endogenous 5′HS4 insulator of the chicken β-globin locus. (A) Schematic representation of the chicken β-globin cluster. Open arrows indicate locations of primer sets used in ChIP analysis. (B-C) Histone-modification patterns at the 5′HS4 insulator element are disrupted in SET1-depleted cells. ChIP analysis of H3K4me2 (B) and H3K9K14ac (C) at the endogenous 5′HS4 region in wild-type (white bars) or SET1 KD (black bars) cells. Relative enrichments were normalized to those observed at the HSA element to adjust for immunoprecipitation efficiency. (D) ChIP analysis of dimethyl H3K9 at the 5′HS4 insulator element. (E) ChIP analysis of BPTF at the 5′HS4 insulator element in 6C2 cells harboring the vector control and shSET1. *P < .01 by Student t test. Shown are the means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments.

The SET1 complex is required for maintaining H3K4 methylation and recruitment of the NURF complex at the endogenous 5′HS4 insulator of the chicken β-globin locus. (A) Schematic representation of the chicken β-globin cluster. Open arrows indicate locations of primer sets used in ChIP analysis. (B-C) Histone-modification patterns at the 5′HS4 insulator element are disrupted in SET1-depleted cells. ChIP analysis of H3K4me2 (B) and H3K9K14ac (C) at the endogenous 5′HS4 region in wild-type (white bars) or SET1 KD (black bars) cells. Relative enrichments were normalized to those observed at the HSA element to adjust for immunoprecipitation efficiency. (D) ChIP analysis of dimethyl H3K9 at the 5′HS4 insulator element. (E) ChIP analysis of BPTF at the 5′HS4 insulator element in 6C2 cells harboring the vector control and shSET1. *P < .01 by Student t test. Shown are the means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments.

The role of the NURF complex in barrier activity

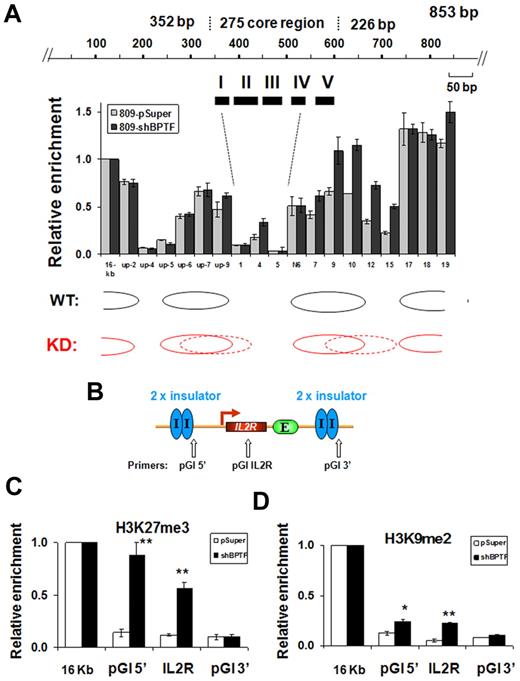

NURF uses the energy derived from ATP hydrolysis to slide nucleosomes on DNA templates.25,27 NURF is involved in transcriptional activation by repositioning the nucleosomes at the promoter regions of active genes.27 The observed effects of NURF KD on barrier activity described above (Figure 3F), together with the finding that NURF associates with insulator-bound USF (Figure 1), suggest that ATP-dependent nucleosome repositioning may be involved in barrier function, perhaps by generating and maintaining a nucleosome-free gap at the insulator site that prevents the extension of repressive chromatin marks. To investigate this possibility, we mapped the positions of nucleosomes at the endogenous 5′HS4 insulator site using a PCR-based nucleosome scanning assay24 in control and BPTF KD 6C2 cells. In the pSuper control, 2 nucleosomes flanked both ends of the cHS4 core insulator and we detected a low nucleosome occupancy over FII to FIV (Figure 6A). In contrast, down-regulation of BPTF resulted in increased nucleosome occupancy in the middle of the core insulator site and within the nucleosome linker region immediately downstream of the insulator site (Figure 6A). In the ectopic IL2R transgene sites, nucleosome rearrangement was accompanied by a drastic increase in H3K27me3 by 6.3-fold at the 5′-flanking cHS4 insulator and by 4.8-fold at the IL2R transgene (Figure 6B-C). However, H3K9me2 in the BPTF KD cells was only increased by 1.9- and 3-fold at the 5′-flanking 5′HS4 site and the IL2R transgene, respectively (Figure 6D). Although SET1-mediated H3K4 methylation affects the recruitment of the NURF complex, inhibiting BPTF expression only moderately affected levels of H3K4me2 (an ∼ 30% reduction compared with an 85% decrease in the hSET1 KD) and H3K9/K14Ac at the endogenous 5′HS4 insulator site (supplemental Figure 6B-C). The reduction in active chromatin marks was even less pronounced at the 5′HS4 insulated transgene in the BPTF KD 809 cells (supplemental Figure 6F-G). In contrast to the drastic decrease of BPTF recruitment in the SET1 KD cells (Figure 4D and Figure 5E), KD of BPTF only slightly reduced the recruitment of SET1 (25%) at the cHS4 insulator (supplemental Figure 6D). These results suggest that NURF might be a downstream effector of SET1 at the cHS4 insulator/barrier. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that the NURF complex might further stabilize SET1 binding. In any case, the data demonstrate that histone H3K4 methylation and ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling activities act synergistically to create a nucleosome-free gap that counteracts the invasion of a condensed repressive chromatin structure.

KD of BPTF results in greater nucleosome occupancy within the 5′HS4 insulator. (A) Mapping of the nucleosome occupancy in the 5′HS4 insulator element by a nucleosome scanning assay in 6C2 809 cells harboring the pSuper control or shBPTF. (B) Schematic representation of the insulated IL2R transgene and the position of PCR primer sets used in ChIP analysis. (C-D) ChIP analysis of trimethyl H3K27 and dimethyl H3K9 at the flanking 5′HS4 sites and at the integrated IL2R transgenes comparing the pSuper control transfected and BPTF KD 809 cells, respectively. *P < .05 and **P < .01 by Student t test. Shown are the means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments.

KD of BPTF results in greater nucleosome occupancy within the 5′HS4 insulator. (A) Mapping of the nucleosome occupancy in the 5′HS4 insulator element by a nucleosome scanning assay in 6C2 809 cells harboring the pSuper control or shBPTF. (B) Schematic representation of the insulated IL2R transgene and the position of PCR primer sets used in ChIP analysis. (C-D) ChIP analysis of trimethyl H3K27 and dimethyl H3K9 at the flanking 5′HS4 sites and at the integrated IL2R transgenes comparing the pSuper control transfected and BPTF KD 809 cells, respectively. *P < .05 and **P < .01 by Student t test. Shown are the means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments.

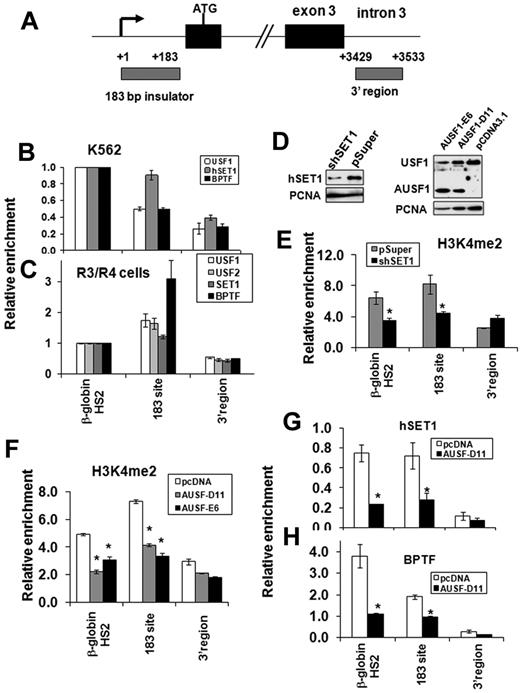

USF1 recruits hSET1 and NURF complexes to the human α-spectrin barrier insulator in vivo

To further investigate whether recruitment of hSET1 and NURF complexes by USF1 is the general underlying mechanism of chromatin barrier activity in mammalian erythroid cells, we explored the co-occupancy of these proteins in a recently identified human barrier insulator associated with the 5′ end of the α-spectrin gene.13 We examined the binding of USF1, hSET1, and BPTF to the 183-bp barrier of the human α-spectrin gene in K562 and cultured human primary erythroid cells (Figure 7A). hSET1 and BPTF colocalized with USF1 at the α-spectrin barrier site in both K562 cells (Figure 7B) and in primary erythroid cells (Figure 7C). In addition, KD of hSET1 resulted in a specific decrease of H3K4me2 at the 183-bp barrier element of the α-spectrin gene, but not in a control region from the 3′region (Figure 7D left and E). However, H3K4me3 levels and recruitment of the TFIID component, TAF3, at the α-spectrin promoter were not affected by the hSET1 KD (supplemental Figure 7A-B). As a result, hSET1 KD has no influence on α-spectrin expression in K562 cells because the locus is a wide open chromatin structure with very low H3K27 methylation in this cell line (data not shown). In addition, KD of SET1 impaired DMSO-induced murine erythroleukemia cell differentiation and decreased β-globin synthesis (supplemental Figure 7C-D). Because USF1 also regulates many genes such as HoxB4 and β-globin, which are important for hematopoiesis,17,28,29 we could not attribute the effects of hSET1 KD solely to a change of insulator function. Nevertheless, our data suggest that USF and hSET1 function as a barrier rather than a transactivator at the α-spectrin locus. Therefore, these data indicate that the recruitment of hSET1 and H3K4 methylation may play an important role in chromatin reorganization during human erythroid cell differentiation and maturation.

USF1 recruits hSET1 and NURF complexes to the human α-spectrin barrier element. (A) Schematic representation of the human α-spectrin gene. Gray boxes indicate locations of primer sets used in ChIP analysis. (B-C) ChIP analysis of USF1, hSET1, and BPTF binding at the 183-bp barrier element of the α-spectrin gene in human erythroid progenitor K562 cells (B) and cultured human primary erythroid cells (C). (D) The effect of hSET1 KD (left) and expression of a dominant-negative USF (AUSF1; right) in K562 cells was analyzed by Western blot. AUSF1 was detected by antibody specific to the C-terminal epitope. (E) ChIP analysis of dimethyl H3K4 in the 183-bp barrier element of the α-spectrin gene in human erythroid K562 cells comparing vector control and hSET1 KD clones. The relative enrichment of dimethyl H3K4 by ChIP analysis was determined in 3 independent experiments. (F) ChIP analysis of dimethyl H3K4 in the 183-bp barrier element of the α-spectrin gene in human erythroid K562 cells harboring the vector control or AUSF. (G-H) ChIP analysis of hSET1 (G) and BPTF (H) recruitment after overexpression of AUSF1 in K562 cells. *P < .01 by Student t test. Shown are the means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments.

USF1 recruits hSET1 and NURF complexes to the human α-spectrin barrier element. (A) Schematic representation of the human α-spectrin gene. Gray boxes indicate locations of primer sets used in ChIP analysis. (B-C) ChIP analysis of USF1, hSET1, and BPTF binding at the 183-bp barrier element of the α-spectrin gene in human erythroid progenitor K562 cells (B) and cultured human primary erythroid cells (C). (D) The effect of hSET1 KD (left) and expression of a dominant-negative USF (AUSF1; right) in K562 cells was analyzed by Western blot. AUSF1 was detected by antibody specific to the C-terminal epitope. (E) ChIP analysis of dimethyl H3K4 in the 183-bp barrier element of the α-spectrin gene in human erythroid K562 cells comparing vector control and hSET1 KD clones. The relative enrichment of dimethyl H3K4 by ChIP analysis was determined in 3 independent experiments. (F) ChIP analysis of dimethyl H3K4 in the 183-bp barrier element of the α-spectrin gene in human erythroid K562 cells harboring the vector control or AUSF. (G-H) ChIP analysis of hSET1 (G) and BPTF (H) recruitment after overexpression of AUSF1 in K562 cells. *P < .01 by Student t test. Shown are the means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments.

To further test whether the binding of hSET1 and NURF complexes to the α-spectrin insulator is dependent on USF1, we stably expressed a dominant-negative USF mutant (AUSF) in K562 cells (Figure 7D right). AUSF lacks the basic DNA-binding region and inhibits both endogenous USF1 and USF2 activity.12 Two selected K562 clones revealed a reduced H3K4me2 abundance at the α-spectrin 183-bp barrier site (Figure 7F). Furthermore, disruption of the USF1 DNA–binding activity eliminated the interactions of both hSET1 and BPTF with the α-spectrin 183-bp barrier site (Figure 7G-H). These data provide further evidence that the recruitment of hSET1 and NURF by USF1 is a critical process for barrier activity in erythroid cells.

Discussion

We recently showed that USF1 and USF2 are important components of a vertebrate barrier insulator that confers on a reporter construct the ability to prevent the encroachment by adjacent transcriptionally silent chromatin in erythroid cells.12 USF-mediated chromatin barriers have been found in chicken β-globin, human α-spectrin, and ankyrin-1 loci that are specifically expressed in mature erythrocytes.5,11,13 During differentiation, the spreading of heterochromatin across the whole erythrocyte genome is a characteristic process of erythroid cell maturation in which the developing erythroblast shuts down the majority of genes while maintaining expression of a few erythroid-specific genes.1 How do erythroid cells achieve such a specific expression pattern during differentiation? We propose that chromatin barrier elements play a critical role in protecting erythroid expression programs by preventing the silencing of genes that encode important functions during maturation of erythroid cells. It was reported recently that mutation of barrier insulators in the human ankyrin-1 locus are associated with ankyrin-deficient hereditary spherocytosis.5 This highlights the importance of barrier activity in protecting erythroid-specific genes from being silenced in an overall heterochromatic environment.

The action of USF in preventing chromosome position effects depends on its ability to recruit histone modifying enzymes responsible for euchromatin-specific histone modifications.11 However, it is not known what enzyme catalyzes the H3K4 di- or trimethylation peak seen in the 5′HS4 insulator site and whether all of the enzymes that are recruited to the 5′HS4 insulator contribute equally to the barrier activity. It is also unknown whether these enzymes act synergistically to render the barrier structure resistant to the spread of heterochromatin formation, which is a common process observed during erythroid differentiation. In the present study, we identified and characterized the USF1-associated hSET1 and NURF complexes and demonstrated that the synergy between hSET1 and NURF contributes to USF1-mediated chromatin barrier activity in erythroid cells.

The cHS4 insulator at the chicken β-globin locus is marked by a peak of H3K4 methylation and histone acetylation regardless of neighboring gene expression.8,9 Our finding that USF1 interacts with the hSET1 complex (Figure 1) and that SET1 components are enriched at the cHS4 insulator (Figure 2) supports a role of SET1 in barrier activity. SET1 belongs to the conserved trithorax family of SET domain–containing proteins that specifically methylate Lys4 residues of histone H3 tails.30 The hSET1 complex shares many structural components with the MLL complex, which is necessary to ensure proper activation of HOX genes during embryogenesis and hematopoiesis.31,32 It has been reported that, in vitro, ASH2L, RBBP5, and WDR5 form a structural platform that brings the SET domain–containing catalytic unit together with substrate histone H3 to facilitate H3K4 methylation.33-35 Consistent with this, disruption of the SET1 complex resulted in a loss of H3K4 methylation, H3 acetylation, and barrier activity (Figures 3,Figure 4–5), revealing that the SET1 complex is the main enzyme responsible for the establishment and maintenance of H3K4 methylation at the cHS4 barrier insulator site.

Depletion of SET1 also led to elimination of BPTF binding to the cHS4 insulator. BPTF is a component of NURF, an ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling complex that alters the positioning of nucleosomes by catalyzing nucleosome sliding, thereby exposing DNA sequences previously associated with nucleosomes.26,27 Depletion of BPTF leads to the movement of nucleosomes into the nucleosome-free regions at the insulator site (Figure 6A). This process increases the density of nucleosomes at the center of the insulator core region. Furthermore, the chromatin at the cHS4 site becomes enriched for H3K27me3 and H3K9me2 marks, the characteristic histone modifications that are seen in repressive heterochromatin regions (Figure 6C-D). Our data therefore suggest a novel mechanism by which NURF is involved in maintaining a nucleosome-free gap at barrier insulators to resist the propagation of condensed heterochromatin structure.

Mammalian genomes encode 2 ISWI genes, SNF2H and SNF2L.36 SNF2H is the ATPase catalytic subunit of numerous protein complexes that catalyze the formation of a regularly ordered nucleosome array37 and facilitate heterochromatin formation and DNA replication.38,39 In contrast, the SNF2L-containing NURF complex is mainly involved in transcriptional activation by interacting with promoters and creating a nucleosome-free region at the promoters.25,27 It is conceivable that a similar mechanism could be used to maintain the epigenetic characteristics of chromatin at the cHS4 insulator. In fact, it has been shown that promoters exhibit insulator/barrier activity.40 It is therefore interesting that USF, which mostly associates with chromatin near the site of transcription,41 also associates with insulator elements. We propose that USF and its associated HMTs and NURF carry out similar functions at promoters and insulators. Unlike promoters, however, the USF-dependent insulator element blocks the recruitment of serine 5 phosphorylated RNA Pol II.12,42

The 5′HS4 insulator at the chicken β-globin locus attracts HMTs, HATs, and, in the present study, NURF complexes. NURF-mediated nucleosome sliding is directly coupled to H3K4 trimethylation by recognizing the H3K4me3 mark,43,44 which suggests that SET1-mediated H3K4 methylation communicates with the NURF complex to facilitate the recruitment of NURF to the 5′HS4 insulator. It is also possible that the SET1 complex may interact directly with the NURF complex and target it to the cHS4 insulator. The KD of SET1 leads to a loss of NURF recruitment (Figure 4D and Figure 5E), supporting the possibility that association of NURF with USF is mediated by SET1. Conversely, NURF-mediated nucleosome remodeling could further stabilize SET1 binding to the insulator element (supplemental Figure 6B-D). In any case, our data demonstrate that SET1 and NURF cooperate to establish barrier activity and that barriers function by acting as chain terminators to block progressive extension of silencing histone modifications by modifying and remodeling nucleosomes during this process. Similar mechanisms have also been reported in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, in which both nucleosome exclusion and histone-modifying complexes have important roles in barrier elements.45,46

An important question remaining to be answered is whether there are other barrier elements in the human genome that use similar molecular mechanisms as those described for the chicken 5′HS4 element. Gallagher et al recently identified barrier elements located at the 5′ exon1′/intron1′ of the α-spectrin gene and 5′HS of the ankyrin-1 gene in human cells.5,13 These elements are bound by the barrier proteins USF1 and USF2 and protect transgenes from silencing by chromosomal position effects in erythrocytes.13 Our present data demonstrate that recruitment of hSET1 and NURF complexes by USF1 is essential for the maintenance of H3K4me2 at the barrier associated with spectrin gene locus and that it is required to confer chromatin barrier function in erythroid cells (Figure 7). Therefore, our results reveal a general molecular mechanism of chromatin barrier activity that is conserved among yeasts, chickens, and humans.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to members of the Huang laboratory for their suggestions and comments.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL091929, HL091929-01A1S1, the ARRA administrative supplement, and HL090589 to S.H.; HL106184 and DK62039 to P.G.G.; DK52356 and DK83389 to J.B.; and HL095674 to Y.Q.). G.F. and C.W. are supported by the Intramural Research Programs, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, respectively.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: X.L. designed the research, performed the experiments, and analyzed the results; S.W., Y.L., C.D., and L.A.S performed the experiments; H.X., C.W., and G.F. contributed vital new reagents; J.B. analyzed the results and contributed vital new reagents; P.G.G. designed the research, performed the experiments, and edited the manuscript; Y.Q. design the research and analyzed the results; and S.H. designed the research, analyzed the results, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Suming Huang, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Florida College of Medicine, PO Box 103633, Gainesville, FL 32610; e-mail: sumingh@ufl.edu.

![Figure 1. USF1 associates with H3K4 methyltransferase hSET1- and nucleosome-remodeling NURF complexes. (A) Partial list of USF1-associated polypeptides identified by LC-MS/MS is shown. (B) Endogenous USF1 associates with hSET1 and NURF complexes in erythroid cells. Nuclear extracts from K562 cells were immunoprecipitated with USF1 and hSET1 antibodies and analyzed by Western blotting. (C) Nuclear extracts from HeLa cells expressing Flag-USF1 were fractionated through a Sephacryl S-300 HR column. The peak fractions from the 1.8-MDa complex (I) corresponding to hSET1, the 300 to 670-kDa complex (II) corresponding to PRMT1 and HATs, and the < 50-kDa complex (III) were collected, respectively. The pooled fractions were immunoprecipitated with Flag antibody. The precipitates were then analyzed by Western blot analysis using antibodies against hSET1, ASH2L, RBBP5, BPTF, and SNF2. (D) USF1 associates with H3K4-specific methyltransferase activity. The purified USF1-associated complexes were incubated with histone H3 peptide or H3K4me3 peptide in the presence of [3H]AdoMet as a cofactor. The proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by fluorography. (E) ATP-dependent nucleosome sliding by the USF1-associated protein complex. A 194-bp DNA fragment containing a strong nucleosome positioning sequence was PCR amplified and assembled with purified HeLa core histones. The nucleosome sliding reactions were carried out with increasing amounts of the purified USF1-associated complexes in the presence or absence of ATP. Mobilized mononucleosomes were analyzed on a native 6% polyacrylamide gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The purified recombinant Drosophila NURF complex was used as a positive control.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/118/5/10.1182_blood-2010-11-319111/4/m_zh89991175670001.jpeg?Expires=1769080026&Signature=Hk1es2PpwgjZCZOtFScPuC1AkMbbPFjqvwRV0~r~355Fum3Ck2BxtBDw7yGhf7h0ROdGCo5-U3yt3D9cwehFANDB0nihplR8N8ZBEPNuIXvfzLe72ba57F9FWrKSP-molgkagsfPEd1menjrdcviWUswl-OAS71KqU8FEMQWWHNCVJHrHRwkt5h3XU1fZtd2Ls~2qx~RKlOSR4NtOPdD0kq39VC4gvMVa6OnvxQksvoNCfw3HyyuwnLqtoKZB0YQfHhaGtnvjaWJu0XhRYXqSxX5n9TmU~PULVSzOuIR38qFQk-z~XZeWTBiPkebH5HNq6zxEfoPEyeQZ-C8V87SlQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal