Abstract

The histone acetyltransferases (HATs) of the MYST family include TIP60, HBO1, MOZ/MORF, and MOF and function in multisubunit protein complexes. Bromodomain-containing protein 1 (BRD1), also known as BRPF2, has been considered a subunit of the MOZ/MORF H3 HAT complex based on analogy with BRPF1 and BRPF3. However, its physiologic function remains obscure. Here we show that BRD1 forms a novel HAT complex with HBO1 and regulates erythropoiesis. Brd1-deficient embryos showed severe anemia because of impaired fetal liver erythropoiesis. Biochemical analyses revealed that BRD1 bridges HBO1 and its activator protein, ING4. Genome-wide mapping in erythroblasts demonstrated that BRD1 and HBO1 largely colocalize in the genome and target key developmental regulator genes. Of note, levels of global acetylation of histone H3 at lysine 14 (H3K14) were profoundly decreased in Brd1-deficient erythroblasts and depletion of Hbo1 similarly affected H3K14 acetylation. Impaired erythropoiesis in the absence of Brd1 accompanied reduced expression of key erythroid regulator genes, including Gata1, and was partially restored by forced expression of Gata1. Our findings suggest that the Hbo1-Brd1 complex is the major H3K14 HAT required for transcriptional activation of erythroid developmental regulator genes.

Introduction

The histone acetyltransferases (HATs) of the MYST family, which include TIP60, HBO1, MOZ/MORF, and MOF, are highly conserved in eukaryotes and perform a significant proportion of all nuclear acetylation. They share a highly conserved MYST domain composed of an acetyl-CoA binding motif and a zinc finger and function in multisubunit protein complexes.1,2 Among the MYST family members, HBO1 and MOZ/MORF form complexes of very similar composition: JADE family proteins bridge HBO1 with inhibitor of growth 4 and 5 (ING4/5) and Esa1-associated factor 6 ortholog (EAF6), whereas BRPF family proteins bridge MOZ/MORF with ING5 and EAF6, respectively.1,3,4 The plant homology domain (PHD) fingers in JADE1/2/3, BRPF1/2/3, and ING4/5 interact with histones and are thought to define the substrate-specificity of the HBO1 and MOZ/MORF complexes.1 HBO1 is considered responsible for the bulk of the acetylation of histone H4 at lysines 5, 8, and 12 (H4K5, K8, and K12), and the interaction between ING4 and histone H3 trimethylated at lysine 4 (H3K4me3) augments activity of HBO1 to acetylate histone H3.5 Furthermore, the HBO1 complexes are enriched throughout the coding regions of genes, suggestive of a role in transcriptional elongation.6 By contrast, MOZ and MORF are HATs specific for histone H3. Binding of Yng1, a yeast ortholog of the ING family, to H3K4me3 has been shown to promote Sas3 (yeast ortholog of MOZ) HAT activity at H3K14.7 The mammalian MOZ complex also showed specificity for H3K14 acetylation in vitro.3

Moz-deficient mice have a severe defect in the maintenance of HSCs.8,9 During zebrafish development, both moz and brpf1 are required for maintenance of cranial Hox gene expression and proper determination of pharyngeal segmental identities.10,11 Similar findings were reported from analyses of Moz-deficient mice and medaka fish in which brpf1 was mutated.12 The genetic interaction between Moz and Brpf1 supports that Brpf1 is the major bridging protein of the MOZ HAT complex. In contrast to Brpf1, however, distinctive functions of other BRPF family members have not been elucidated.

BRD1 (initially named BR140-LIKE; BRL) was originally cloned as a protein containing a cysteine-rich region related to that of AF10 and AF17, which are leukemic fusion partners of MLL.13 BRD1 contains a bromodomain, 2 PHD zinc fingers, and a proline-tryptophan-tryptophan-proline (PWWP) domain, 3 types of modules characteristic of chromatin regulators. Recently, BRD1 was reported to belong to a small family of BRPF proteins that includes BRPF1, BRD1/BRPF2, and BRPF3.1,3 BRD1 has been considered a subunit of the MOZ/MORF H3 HAT complex on the basis of analogy with BRPF1 and BRPF3.3,4 However, no detailed analysis of BRD1 has been reported. In this study, we found that BRD1 forms a novel HAT complex with HBO1 and is responsible for the bulk of the acetylation of H3K14. We confirmed a drastic reduction in levels of acetylated H3K14 in Brd1-deficient mice and found that the Hbo1-Brd1 HAT complex is required for full transcriptional activation of the erythroid-specific regulator genes essential for terminal differentiation and survival of erythroblasts in fetal liver.

Methods

Gene targeting of Brd1

Brd1-deficient mice were generated by the use of R1 embryonic stem cells according to the conventional protocol. Brd1-deficient mice were backcrossed to the C57BL/6 background > 5 times. All experiments in which mice were used received approval from the Chiba University Administrative Panel for Animal Care.

Viral production

To prepare the retrovirus, pMC-ires-GFP was used as a vector.14 The production and concentration of the recombinant retrovirus have been described previously.15 To prepare the lentivirus, pCSII-EF1-MCS-IRESII-Venus and pCS-H1-shRNA-EF-1α-EGFP were used as vectors.16 The viruses were produced as described previously.16 Target sequences were as follows; Sh-mHbo1#2; GAGGGAAGCAACATGATTA, Sh-mHbo1#3; GTGATGAGATTTATCGCAA, Sh-hHBO1#1; GGGATAAGCAGATAGAAGA, and Sh-hHBO1#3; CTCAAATACTGGAAGGGAA.

Purification of BRD1-containing protein complex

Protein purification, trypsin digestion, and liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) were performed as described previously.17 In brief, K562 cells expressing Flag-Brd1 (2.5 × 108 cells) were suspended in 15 mL of lysis buffer (20mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0; 350mM NaCl; 30mM sodium pyrophosphate; 0.1% NP-40; 5mM EDTA; 10mM NaF; 0.1mM Na3VO4; and 1mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) containing protease inhibitors (cOmplete mini; Roche) and sonicated for 20 minutes. The lysates were cleared by centrifugation and incubated with 100 μL of anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma-Aldirch) with rotation at 4°C for 16 hours. The beads were extensively washed 6 times with 15 mL of lysis buffer. The complexes were eluted by incubating twice with 0.2 mg/mL of FLAG peptide in 300 μL of lysis buffer for 2.5 hours. This purification was repeated 10 times. Then, eluents were pooled and concentrated by the use of a filtration device (Vivaspin 10K-PES; Sartorius) and separated by 7.5%-15% SDS-PAGE.

Immunoprecipitation and extraction of histones

Transfected 293T cells were lysed in lysis buffer containing 250mM NaCl and then immunoprecipitation was performed. Immunocomplexes were eluted with FLAG peptide as describe previously. Histone proteins were extracted following the method described previously.18

ChIP-on-chip experiment

ChIP-on-chip analyses of BRD1 and HBO1 binding were performed by use of the Human Promoter ChIP-on-chip Microarray Set (G4489A; Agilent Technologies). The assignment of IP regions and calculations were performed as described.19 K562 cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 minutes at room temperature and washed twice with PBS. Fixed cells swelled in the buffer (20mM HEPES, pH 7.8; 1.5mM MgCl2; 10mM KCl; 0.1% NP-40; and 1mM DTT) for 10 minutes on ice and nuclei were prepared by Dounce homogenizer. Nuclei were then lysed with RIPA (10mM Tris, pH 8.0; 0.5% SDS; 140mM NaCl; 1mM EDTA; 1% TritonX-100; 0.1% SDS; 0.1% sodium deoxycholate; and a proteinase inhibitor cocktail [cOmplete mini]), and sonicated for 30 minutes with a Bioruptor (Cosmobio Co Ltd). After centrifugation, the soluble chromatin fraction was precleared with a mixture of protein A and G-conjugated Dynabeads (Invitrogen) blocked with BSA and salmon sperm DNA. Three hundred micrograms of chromatin was immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C with the use of 25 μL of antibody-conjugated Dynabeads. The immunoprecipitates were washed extensively and subjected to a quantitative PCR analysis with SYBR Premix Ex TaqTM II (Takara). For the ChIP of erythroblasts, the steps to prepare nuclei were omitted, and fixed cells were directly lysed by RIPA. Primer sequences used are listed in supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Expression vectors and antibodies

Other methods, the expression vectors, and antibodies used are described in supplemental Methods.

Results

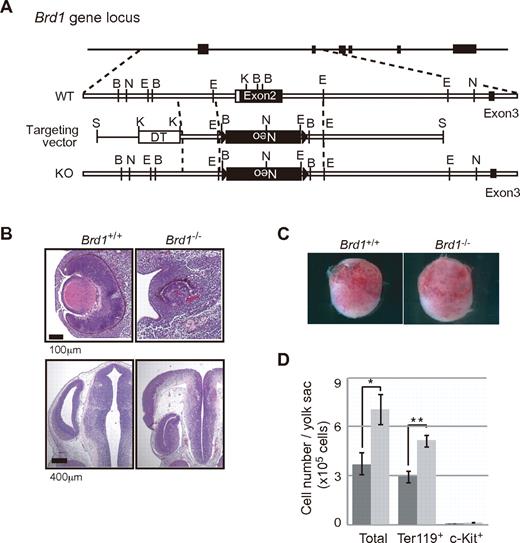

Brd1−/− embryos die at mid-gestation because of anemia

To clarify the physiologic function of Brd1, we generated Brd1-deficient mice in which exon 2 containing the first ATG of the Brd1 gene was deleted (Figure 1A). Northern blot analysis detected no Brd1 mRNA in Brd1−/− embryos (data not shown). The Brd1−/− embryos were recovered at nearly the expected Mendelian ratio at 12.5 days postcoitum (dpc) but most had died by 15.5 dpc (Table 1). Brd1−/− embryos showed growth retardation (92 of 99 embryos at 12.5 dpc), failure to fuse the neural tube (30 of 135 embryos at 8.5-12.5 dpc), and abnormal lenses with disoriented optic cups (74 of 122 embryos at 10.5-12.5 dpc; Figure 1B and Table 1). These results indicated Brd1 as having pivotal roles in embryonic development in multiple tissues and organs, but none of them was considered to be the cause of death.

Targeted disruption of the mouse Brd1 gene. (A) Strategy for making a knockout allele for Brd1 by homologous recombination in ES cells. B, BamHI; N, NcoI; E, EcoRI; K, KpnI; S, SalI. (B) Developmental defects in Brd1−/− embryos. Abnormal lenses with disoriented optic cups (top) and neural tube disclosure (bottom) in Brd1−/− embryos at 12.5 dpc. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. (C) Appearance of wild-type (Brd1+/+, left) and Brd1−/− (right) yolk sac at 10.5 dpc. (D) Absolute numbers of total cells, c-Kit+ hematopoietic progenitors, and Ter119+ erythroid cells in 10.5 dpc yolk sac from wild-type (left bar, n = 5) and Brd1−/− (right bar, n = 3) embryos. The results are shown as the mean ± SE *P < .05, **P < .005.

Targeted disruption of the mouse Brd1 gene. (A) Strategy for making a knockout allele for Brd1 by homologous recombination in ES cells. B, BamHI; N, NcoI; E, EcoRI; K, KpnI; S, SalI. (B) Developmental defects in Brd1−/− embryos. Abnormal lenses with disoriented optic cups (top) and neural tube disclosure (bottom) in Brd1−/− embryos at 12.5 dpc. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. (C) Appearance of wild-type (Brd1+/+, left) and Brd1−/− (right) yolk sac at 10.5 dpc. (D) Absolute numbers of total cells, c-Kit+ hematopoietic progenitors, and Ter119+ erythroid cells in 10.5 dpc yolk sac from wild-type (left bar, n = 5) and Brd1−/− (right bar, n = 3) embryos. The results are shown as the mean ± SE *P < .05, **P < .005.

Analysis of Brd1-heterozygous intercross progenies

| Stage, dpc . | Brd1+/+ . | Brd1+/− . | Brd1−/− . | ND . | Total progenies . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8.5-9.5 | 5 | 20 | 13 (1)*† | 3 | 41 |

| 10.5-11.5 | 24 | 49 | 23 (2)द | 5 | 101 |

| 12.5 | 117 | 238 (2) | 99 (4)#‖** | 44 | 498 |

| 13.5 | 10 | 15 | 2†† | 1 | 28 |

| 14.5-15.5 | 4 | 22 | 1 | 6 | 23 |

| 16.5-18.5 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 13 | 20 |

| Weaning | 17 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 40 |

| Stage, dpc . | Brd1+/+ . | Brd1+/− . | Brd1−/− . | ND . | Total progenies . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8.5-9.5 | 5 | 20 | 13 (1)*† | 3 | 41 |

| 10.5-11.5 | 24 | 49 | 23 (2)द | 5 | 101 |

| 12.5 | 117 | 238 (2) | 99 (4)#‖** | 44 | 498 |

| 13.5 | 10 | 15 | 2†† | 1 | 28 |

| 14.5-15.5 | 4 | 22 | 1 | 6 | 23 |

| 16.5-18.5 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 13 | 20 |

| Weaning | 17 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 40 |

Numbers in parentheses indicate dead embryos.

dpc indicates days postcoitum; and ND, not determined.

Six embryos showed growth retardation.

Four embryos showed failure to fuse the neural tube.

Twenty-one embryos showed growth retardation.

Two embryos showed failure to fuse the neural tube.

Three embryos showed abnormal eye development.

Ninety-two embryos showed growth retardation.

Twenty-four embryos showed failure to fuse the neural tube.

Seventy-one embryos showed abnormal eye development.

One embryo showed abnormal eye development.

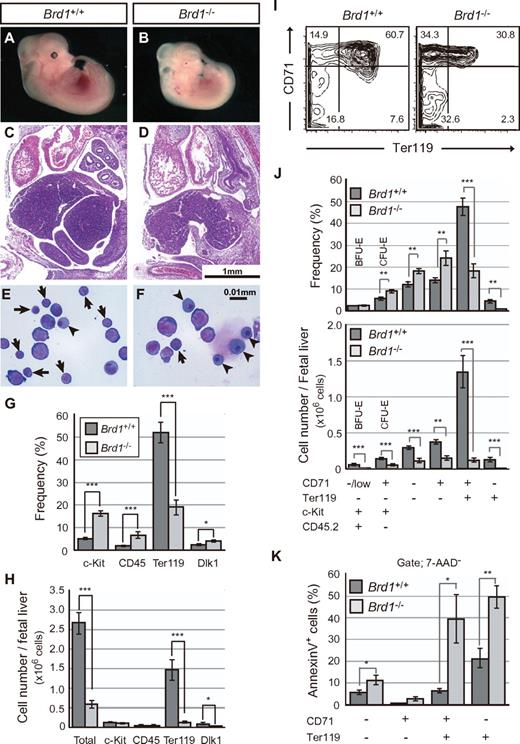

We then analyzed hematopoiesis in the absence of Brd1. Numbers of total yolk sac cells and Ter119+ erythroblasts were rather increased in Brd1−/− yolk sac compared with those in wild-type yolk sac (Figure 1C-D). This trend was more apparent at later stages. At 12.5 dpc, erythropoiesis was still active in Brd1−/− yolk sac, whereas erythropoiesis tended to decline in wild-type yolk sac (supplemental Figure 1A). Together, our findings suggest that primitive erythropoiesis in the Brd1−/− yolk sac was not affected but rather enhanced. Nevertheless, Brd1−/− embryos at 12.5 dpc were pale and the fetal liver, in which fetal hematopoiesis mainly occurs, was significantly smaller than that of littermate controls (Figure 2A-D). Cytologic analysis revealed that Brd1−/− fetal livers had profoundly fewer erythroblasts beyond the proerythroblast stage than did wild-type fetal livers (Figure 2E-F).

Impaired hematopoiesis in Brd1−/− fetal liver. Appearance of wild-type (A) and Brd1−/− (B) embryos at 12.5 dpc. H&E-stained transverse sections of 12.5 dpc wild-type (C) and Brd1−/− (D) embryos. Morphology of 12.5 dpc fetal liver hematopoietic cells from wild-type (E) and Brd1−/− (F) embryos stained with May-Grüenwald-Giemsa solutions. Arrows and arrowheads indicate mature erythroblasts and nucleated erythrocytes, respectively. Frequency (G) and absolute cell numbers (H) of c-Kit+ hematopoietic progenitors, CD45+ hematopoietic cells, Ter119+ erythroid cells, and Dlk1+ hepatoblasts in 12.5 dpc fetal livers from wild-type and Brd1−/− embryos. The results are shown as the mean ± SE (n ≥ 4). *P < .05, ***P < .0005. (I) Flow cytometric profiles of erythroid differentiation defined by CD71 and Ter119 expression in representative fetal livers at 12.5 dpc. The percentage of each fraction is indicated. (J) Frequency (top) and absolute cell numbers (bottom) of BFU-E, CFU-erythroid, CD71−Ter119− cells, CD71+Ter119− erythroblasts, CD71+Ter119+ erythroblasts, and CD71−Ter119+ erythroblasts in 12.5 dpc fetal livers from wild-type and Brd1−/− embryos. The results are shown as the mean ± SE (n ≥ 8). **P < .005, ***P < .0005. (K) Massive apoptosis of Brd1−/− erythroblasts. The percentage of annexin V+/7-aminoactinomycin D− (7-AAD−) apoptotic cells in each fraction defined by CD71 and Ter119 is shown as the mean ± SE (n ≥ 4). *P < .05, **P < .005.

Impaired hematopoiesis in Brd1−/− fetal liver. Appearance of wild-type (A) and Brd1−/− (B) embryos at 12.5 dpc. H&E-stained transverse sections of 12.5 dpc wild-type (C) and Brd1−/− (D) embryos. Morphology of 12.5 dpc fetal liver hematopoietic cells from wild-type (E) and Brd1−/− (F) embryos stained with May-Grüenwald-Giemsa solutions. Arrows and arrowheads indicate mature erythroblasts and nucleated erythrocytes, respectively. Frequency (G) and absolute cell numbers (H) of c-Kit+ hematopoietic progenitors, CD45+ hematopoietic cells, Ter119+ erythroid cells, and Dlk1+ hepatoblasts in 12.5 dpc fetal livers from wild-type and Brd1−/− embryos. The results are shown as the mean ± SE (n ≥ 4). *P < .05, ***P < .0005. (I) Flow cytometric profiles of erythroid differentiation defined by CD71 and Ter119 expression in representative fetal livers at 12.5 dpc. The percentage of each fraction is indicated. (J) Frequency (top) and absolute cell numbers (bottom) of BFU-E, CFU-erythroid, CD71−Ter119− cells, CD71+Ter119− erythroblasts, CD71+Ter119+ erythroblasts, and CD71−Ter119+ erythroblasts in 12.5 dpc fetal livers from wild-type and Brd1−/− embryos. The results are shown as the mean ± SE (n ≥ 8). **P < .005, ***P < .0005. (K) Massive apoptosis of Brd1−/− erythroblasts. The percentage of annexin V+/7-aminoactinomycin D− (7-AAD−) apoptotic cells in each fraction defined by CD71 and Ter119 is shown as the mean ± SE (n ≥ 4). *P < .05, **P < .005.

Brd1 is required for erythropoiesis in fetal liver

Among the phenotypes associated with Brd1 deficiency, we focused on anemia, which is a major causative defect for lethality at this stage of development. Flow cytometric analysis of fetal livers at 12.5 dpc revealed a 2-fold reduction in the Ter119+ erythroid cell fraction and a 2-fold increase in the c-Kit+ hematopoietic progenitor fraction (Figure 2G). Because the total number of Brd1−/− fetal liver cells was decreased to 22% of the control, the absolute number of Ter119+ erythroid cells was decreased by 91% in Brd1−/− fetal livers compared with wild-type fetal livers, whereas that of c-Kit+ hematopoietic progenitors was not profoundly changed (Figure 2H). The number of Dlk1+ hepatoblasts was reduced to 57% of the control, but the differentiation of hepatoblasts into hepatocytes and cholangiocytes was grossly normal in the Brd1−/− fetal liver (Figure 2G-H; and data not shown). These results indicated that the fetal liver hypoplasia in Brd1−/− embryos was mainly caused by a reduction in numbers of erythroid lineage cells.

Detailed flow cytometric analyses revealed a significant increase in the CD71+Ter119− fraction and a drastic reduction in the CD71+Ter119+ and CD71−Ter119+ fractions in Brd1−/− fetal livers compared with wild-type fetal livers (Figure 2I-J). The CD45−c-Kit+CD71+Ter119− CFU-erythroid fraction was also more prevalent in Brd1−/− fetal livers (Figure 2J top). These results indicate a differentiation block of Brd1−/− fetal liver erythroblasts at the transition from CD71+Ter119− to CD71+Ter119+ stage. Nonetheless, absolute numbers of cells in each fraction, particularly the CD71+Ter119+ and CD71−Ter119+ fractions, were significantly decreased (Figure 2J bottom). To further elucidate the mechanism by which Brd1 deficiency causes defective erythropoiesis, we examined the apoptosis of erythroblasts. Apoptotic cells with an active caspase-3 were readily detected in Brd1−/− fetal livers (supplemental Figure 1B). The number of annexin V+/7-aminoactinomycin D− apoptotic cells was also significantly elevated in Brd1−/− fetal livers; cell death was even further exacerbated in the CD71+Ter119+ and CD71−Ter119+ fractions (Figure 2K). Thus, loss of Brd1 in fetal liver erythroblasts causes massive apoptosis and maturation delay, leading to severe anemia. These findings suggested that severe anemia combined with other physiologic defects accounts for the death of Brd1−/− embryos.

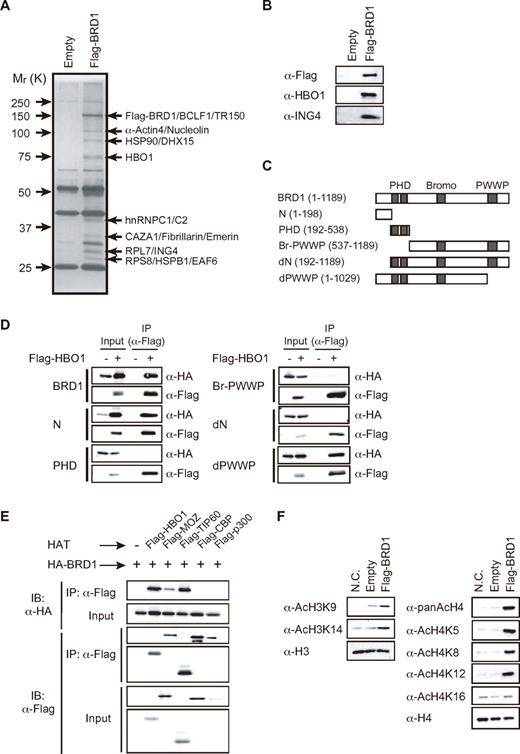

BRD1 forms an active HAT complex with HBO1 and ING4

Analogous to BRPF1, BRD1/BRPF2 has been proposed to form a H3 HAT complex with MOZ.3,4 Similar to Brd1−/− mice, Moz−/− mice die in the embryonic stage and show impaired fetal liver hematopoiesis. However, the hematopoietic defect in Moz−/− fetal livers is observed mainly in HSCs.8,9 To address this discrepancy, we purified BRD1-containing protein complexes by Flag epitope-specific immune-affinity purification from K562 human leukemic cells expressing Flag-BRD1 and analyzed them by LC/MS/MS (Figure 3A). The LC/MS/MS analysis identified several proteins as putative components of the BRD1 complex. Among these proteins, we focused on ING4 and HBO1 because HBO1 and ING4 were reproducibly and substoichiometrically copurified with Flag-BRD1 in our repeated purifications. Immunoblotting of the purified fraction confirmed the presence of HBO1 and ING4 in the complex (Figure 3B). HBO1 and MOZ have been demonstrated to form similar protein complexes with ING4/5, JADE1/2/3, and hEAF6 and ING5, BRPF1/2/3, and hEAF6, respectively, in HeLa cells.1,2 JADE and BRPF family proteins function as a bridging protein between HBO1 and ING4/5 and MOZ and ING5, respectively.

BRD1 forms a HAT complex with HBO1. (A) Purification of the BRD1 complex. Flag-tagged BRD1 protein was partially purified from lysates of K562/Flag-BRD1 cells using an anti-Flag antibody. (B) Western blot analysis of the purified BRD1 complex in panel A by the use of indicated antibodies. (C) Schematic representation of BRD1 and its deletion mutants. Three major domains are indicated. (D) Localization of the binding site in BRD1 for HBO1. 293T cells were transfected with HA-tagged BRD1 mutants with and without Flag-tagged HBO1. Proteins in the lysates of the transfectants were immunoprecipitated with the anti-FLAG antibody and eluted with an excess of Flag peptide. The eluents were analyzed by Western blotting by the use of anti-Flag or HA antibodies. (E) Affinity of BRD1 for the MYST family HATs (HBO1, MOZ, and Tip60) and CBP/p300. 293T cells were transfected with HA-tagged Brd1 together with indicated Flag-tagged HATs. Proteins in the lysates of the transfectants were immunoprecipitated with the anti-FLAG antibody. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-Flag and HA antibodies. (F) HAT activity of the BRD1 complex. The BRD1 complex was partially purified from lysates of K562/empty vector (Empty) and K562/Flag-BRD1 cells by the use of the anti-Flag antibody and HAT activity on recombinant histones H3 and H4 was evaluated. As a negative control (N.C.), the recombinant histones H3 and H4 were similarly treated without HAT complexes.

BRD1 forms a HAT complex with HBO1. (A) Purification of the BRD1 complex. Flag-tagged BRD1 protein was partially purified from lysates of K562/Flag-BRD1 cells using an anti-Flag antibody. (B) Western blot analysis of the purified BRD1 complex in panel A by the use of indicated antibodies. (C) Schematic representation of BRD1 and its deletion mutants. Three major domains are indicated. (D) Localization of the binding site in BRD1 for HBO1. 293T cells were transfected with HA-tagged BRD1 mutants with and without Flag-tagged HBO1. Proteins in the lysates of the transfectants were immunoprecipitated with the anti-FLAG antibody and eluted with an excess of Flag peptide. The eluents were analyzed by Western blotting by the use of anti-Flag or HA antibodies. (E) Affinity of BRD1 for the MYST family HATs (HBO1, MOZ, and Tip60) and CBP/p300. 293T cells were transfected with HA-tagged Brd1 together with indicated Flag-tagged HATs. Proteins in the lysates of the transfectants were immunoprecipitated with the anti-FLAG antibody. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-Flag and HA antibodies. (F) HAT activity of the BRD1 complex. The BRD1 complex was partially purified from lysates of K562/empty vector (Empty) and K562/Flag-BRD1 cells by the use of the anti-Flag antibody and HAT activity on recombinant histones H3 and H4 was evaluated. As a negative control (N.C.), the recombinant histones H3 and H4 were similarly treated without HAT complexes.

To determine the physical interaction among HBO1, BRD1, and ING4 in the complex, we transfected 293T cells with different combinations of BRD1, HBO1, and ING4. HBO1 and ING4 were coimmunoprecipitated only in the presence of BRD1, whereas BRD1 was coimmunoprecipitated with HBO1 or ING4 in the absence of ING4 and HBO1, respectively (supplemental Figure 2A-C). These results indicate that BRD1 functions as a scaffold to link HBO1 with ING4 and form a ternary complex. To confirm the formation of a complex between the endogenous Brd1 and Hbo1 proteins, we immunoprecipitated Brd1 with an anti-Brd1 antibody from both wild-type and Brd1−/− whole embryos at 12.5 dpc. Of note, Hbo1 was detected in the immunoprecipitates from wild-type but not Brd1−/− embryos (supplemental Figure 2E).

The Brd1 mutants containing the N-terminal 198 amino acids (N and dPWWP) interacted with HBO1, whereas fragments lacking the N-terminal 192 amino acids did not (PHD, Br-PWWP, and dN; (Figure 3C-D). These results indicate that the N-terminal 198 amino acids of BRD1 are necessary and sufficient for physical interaction with HBO1. Conversely, the BRD1-interacting domain was localized to the MYST domain of HBO1 (supplemental Figure 2D). We then tested whether the complementation of Brd1−/− progenitors with exogenous Brd1 can rescue their compromised erythroid differentiation in vitro. We purified c-Kit+CD71− hematopoietic progenitors from 12.5 dpc fetal livers. The cells were retrovirally transduced with the wild-type Brd1 or dN mutant and then cultured for 3 days in the presence of erythropoietin (EPO) to induce erythroid differentiation (supplemental Figure 3). As expected, wild-type Brd1 but not dN mutant considerably canceled the differentiation block of Brd1−/− erythroblasts at the transition from CD71+Ter119− to CD71+Ter119+ stage. These results further support the formation of a complex between BRD1 and HBO1 through the N terminus of Brd1.

We also noted that coexpression of HBO1 increases the protein level of BRD1 (Figure 3D; see inputs of BRD1, N, and dPWWP) in 293T cells. The treatment of the cells with MG132, a proteasome inhibitor, also increased the BRD1 protein level, strongly suggesting that HBO1 stabilizes the BRD1 protein by inhibiting the proteasome-dependent protein degradation pathway (supplemental Figure 4A). Similar levels of protein stabilization were observed when HBO1 was coexpressed with BRD1 deletions retaining an HBO1-binding capacity, but not dN, which lacked the HBO1-binding domain (supplemental Figure 4A), indicating that the N-terminal 198 amino acids are required not only for BRD1-HBO1 interaction but also for stability of the BRD1 protein. These findings further support the formation of a complex between BRD1 and HBO1.

We then examined the interaction of BRD1 with various HATs. Coimmunoprecipitation assays demonstrated that BRD1 binds mainly to HBO1 and TIP60, moderately to MOZ, and not at all to CBP and p300 (Figure 3E). In contrast, BRPF1 preferred MOZ and bound moderately to HBO1 (supplemental Figure 4B). The difference in affinity for HATs between BRD1 and BRPF1 was evident when they were forced to compete with each other to form complexes. This experiment clearly showed that BRD1 and BRPF1 prefer to bind with HBO1 and MOZ, respectively (supplemental Figure 4C).

The HBO1 HAT complex is reportedly responsible for the bulk of the acetylation of H4K5, K8, and K12 and also acetylates histone H3.3,5,20 The BRD1 complex from K562 cells efficiently acetylated the recombinant histone H4 at K5, K8, and K12, but not K16, and moderately acetylated the recombinant histone H3 at K9 and 14 (Figure 3F). These findings implied that BRD1 and HBO1 form a novel HAT complex that differs in composition from known HAT complexes.

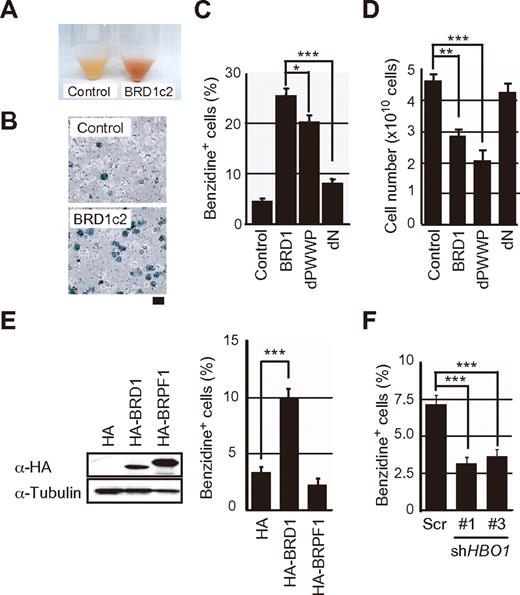

The HBO1-BRD1 complex promotes erythroid differentiation

K562 human leukemic cells, which we used for purification of the BRD1 complex, have a potential to differentiate along the erythroid lineage. We found that overexpression of BRD1 promotes hemoglobinization of K562 cells (clone BRD1c2, Figure 4A). Enhanced hemoglobin production was confirmed by benzidine staining in BRD1c2 (Figure 4B, benzidine-positive cells, control cells 5.3% ± 0.4% vs BRD1c2 18.4% ± 0.3%) and in a series of other clones (supplemental Figure 5A-B, control cells 5.7% ± 2.3% vs Flag-BRD1 25.6% ± 6.7%). Expression of glycophorin A, an erythroid lineage marker antigen, on the cell surface, was also significantly increased in the BRD1-overexpressing clones (supplemental Figure 5C-D, control cells 29.0% ± 0.3% vs Flag-BRD1 72.0% ± 0.2%). These results indicated that BRD1 induces erythroid differentiation of K562 cells.

Overexpression of BRD1 induces erythroid differentiation in K562. (A) Appearance of parental K562 cells (Control) and the Flag-BRD1-expressing clone (BRD1c2) used for purification of the BRD1 complex. (B) Benzidine staining of parental K562 cells (Control) and Brd1c2. The bar indicates 20 μm (C) Benzidine staining of K562 cells expressing BRD1 mutants. K562 cells were transduced with an empty vector (Control) or retroviruses expressing full-length BRD1 (BRD1), dPWWP, or dN. Transduced cells were sorted with the use of GFP as a marker antigen and expanded for benzidine staining. Bars represent mean ± SE (n = 12). (D) Growth of K562 cells expressing BRD1 or the BRD1 mutant in (C). The results are shown as the mean ± SE for triplicate cultures. (E) Overexpression of BRPF1 in K562 cells. K562 cells were transduced with a HA-BRPF1 retrovirus, and BRPF1 expression was detected by Western blotting by use of the anti-HA antibody (left). Effects of BRPF1 on erythroid differentiation of K562 cells were evaluated by benzidine staining. The data are shown as the mean ± SE for triplicate cultures. (F) Knockdown of HBO1 with the use of shRNA. K562 cells were infected with lentiviruses expressing shRNAs against HBO1 and analyzed as to the basal status of hemoglobinization by benzidine staining. The results are shown as the mean ± SE for triplicate cultures. *P < .05, **P < .005, ***P < .0005.

Overexpression of BRD1 induces erythroid differentiation in K562. (A) Appearance of parental K562 cells (Control) and the Flag-BRD1-expressing clone (BRD1c2) used for purification of the BRD1 complex. (B) Benzidine staining of parental K562 cells (Control) and Brd1c2. The bar indicates 20 μm (C) Benzidine staining of K562 cells expressing BRD1 mutants. K562 cells were transduced with an empty vector (Control) or retroviruses expressing full-length BRD1 (BRD1), dPWWP, or dN. Transduced cells were sorted with the use of GFP as a marker antigen and expanded for benzidine staining. Bars represent mean ± SE (n = 12). (D) Growth of K562 cells expressing BRD1 or the BRD1 mutant in (C). The results are shown as the mean ± SE for triplicate cultures. (E) Overexpression of BRPF1 in K562 cells. K562 cells were transduced with a HA-BRPF1 retrovirus, and BRPF1 expression was detected by Western blotting by use of the anti-HA antibody (left). Effects of BRPF1 on erythroid differentiation of K562 cells were evaluated by benzidine staining. The data are shown as the mean ± SE for triplicate cultures. (F) Knockdown of HBO1 with the use of shRNA. K562 cells were infected with lentiviruses expressing shRNAs against HBO1 and analyzed as to the basal status of hemoglobinization by benzidine staining. The results are shown as the mean ± SE for triplicate cultures. *P < .05, **P < .005, ***P < .0005.

To understand the mechanism of the BRD1-mediated erythroid differentiation, we examined the impact of BRD1 deletions on erythroid differentiation of K562 cells. The capacity of BRD1 to induce erythroid differentiation was profoundly affected by deletion of the N-terminus, which mediates interaction with HBO1 (dN mutant; Figure 4C), although the dN mutant was expressed and localized to the nucleus (data not shown). In contrast, the C-terminal deletion mutant (dPWWP) still had a significant effect (Figure 4C). Both BRD1 and dPWWP significantly reduced cell growth probably as a consequence of erythroid differentiation (Figure 4D). These results indicate that the HBO1-binding domain is indispensable for BRD1 to induce erythroid differentiation. We also tested the effect of BRPF1, which mostly binds to MOZ, and found that BRPF1 does not induce erythroid differentiation (Figure 4E), implying that the HBO1-BRD1 complex has a distinct function from the MOZ-BRPF1 complex in erythroid cells. We then examined whether HBO1 has a significant impact on erythroid differentiation by knocking down its expression. We transduced K562 cells with lentiviruses expressing shRNA against the human HBO1 (shHBO1#1 and #3) and a scrambled control shRNA sequence. The percentages of benzidine+ cells were significantly reduced by HBO1 knockdown even in uninduced K562 cells (Figure 4F).

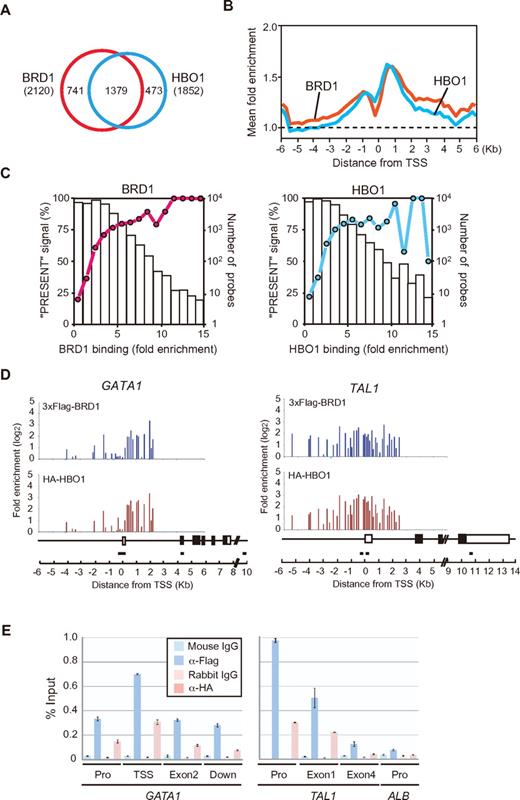

Localization of the HBO1-BRD1 complex in the human genome

To identify the direct target genes of the HBO1-BRD1 complex, we conducted a ChIP-on-chip analysis in K562 cells coexpressing 3xFlag-BRD1 and HA-HBO1, and we identified 2120 and 1852 genes bound by BRD1 and HBO1, respectively (full data are listed in supplemental ChIP-chip dataset). Of these, 1379 genes were co-occupied by BRD1 and HBO1, indicating that BRD1 and HBO1 coregulate a significant portion of their target genes in erythroid cells (Figure 5A). The peaks of BRD1 and HBO1 signals coincided around −1.0 kb and 1.0 kb from the transcription start site (TSS; Figure 5B). Then, we examined the relationship between the degree of HBO1-BRD1 binding and transcription status by using published data on expression profiles of K562 cells examined with microarrays.21 The HBO1- or BRD1-occupied genes tended to be expressed in K562 cells (Figure 5C), indicating that the HBO1-BRD1 complex generally activates transcription of their target genes. The functional annotation of the set of genes bound by both BRD1 and HBO1 was performed on the basis of gene ontology and showed significant enrichment for genes that fell into the categories “transcriptional coactivator activity” (P < .015), “transcriptional factor activity” (P < .018), and “structural constituent of the ribosome” (P < .042).

BRD1 and HBO1 coregulate erythroid genes. (A) ChIP-chip analysis of BRD1 and HBO1 binding in K562 cells. A ChIP-chip analysis was performed in K562 cells coexpressing 3xFlag-BRD1 and HA-HBO1 by use of anti-Flag and HA antibodies. Fold enrichment > 4 was judged as positive. The number of genes in each category of the Venn diagram is indicated. (B) Average BRD1 and HBO1 binding was depicted in the promoter regions (from −6 kb to +6 kb relative to the transcription start site) of all genes in the ChIP-on-chip analysis. The dotted line represents the normalized average signal over the entire chip. (C) Graph of the correlation of expressed genes in K562 cells in terms of the degree of BRD1 or HBO1 binding. Gene expression profiles of K562 cells examined with microarrays were used to judge the transcriptional status of the BRD1- or HBO1-occupied genes identified in the ChIP-chip analysis. The percentage of probes that produced “PRESENT” signals in the microarray analysis was plotted against the BRD1 or HBO1 binding detected in the ChIP-on-chip analysis. (D) ChIP-on-chip signals in the GATA1 and TAL1 promoter regions. Blue columns indicate the probes with no signals. The GATA1 and TAL1 gene structures and the location of the primer sets are depicted. (E) ChIP analyses at the GATA1 and TAL1 loci. The binding of BRD1 and HBO1 to the indicated regions of the GATA1 and TAL1 genes was determined by ChIP and site-specific real-time PCR. The relative amount of immunoprecipitated DNA is depicted as a percentage of input DNA. The data are shown as the mean ± SE for triplicate PCRs. The ALB promoter served as a negative control. Pro indicates promoter; and Down, 3 kb downstream from the polyadenylation site.

BRD1 and HBO1 coregulate erythroid genes. (A) ChIP-chip analysis of BRD1 and HBO1 binding in K562 cells. A ChIP-chip analysis was performed in K562 cells coexpressing 3xFlag-BRD1 and HA-HBO1 by use of anti-Flag and HA antibodies. Fold enrichment > 4 was judged as positive. The number of genes in each category of the Venn diagram is indicated. (B) Average BRD1 and HBO1 binding was depicted in the promoter regions (from −6 kb to +6 kb relative to the transcription start site) of all genes in the ChIP-on-chip analysis. The dotted line represents the normalized average signal over the entire chip. (C) Graph of the correlation of expressed genes in K562 cells in terms of the degree of BRD1 or HBO1 binding. Gene expression profiles of K562 cells examined with microarrays were used to judge the transcriptional status of the BRD1- or HBO1-occupied genes identified in the ChIP-chip analysis. The percentage of probes that produced “PRESENT” signals in the microarray analysis was plotted against the BRD1 or HBO1 binding detected in the ChIP-on-chip analysis. (D) ChIP-on-chip signals in the GATA1 and TAL1 promoter regions. Blue columns indicate the probes with no signals. The GATA1 and TAL1 gene structures and the location of the primer sets are depicted. (E) ChIP analyses at the GATA1 and TAL1 loci. The binding of BRD1 and HBO1 to the indicated regions of the GATA1 and TAL1 genes was determined by ChIP and site-specific real-time PCR. The relative amount of immunoprecipitated DNA is depicted as a percentage of input DNA. The data are shown as the mean ± SE for triplicate PCRs. The ALB promoter served as a negative control. Pro indicates promoter; and Down, 3 kb downstream from the polyadenylation site.

Of note, targets included erythroid master regulator genes, GATA1, TAL1/SCL, and LMO2, and other regulator genes such as CBFA2T3/ETO2, STAT5A, and STAT5B (supplemental Table 1). The binding of HBO1 and BRD1 was detected throughout the coding regions of genes with peaks around TSS (Figure 5D-E).

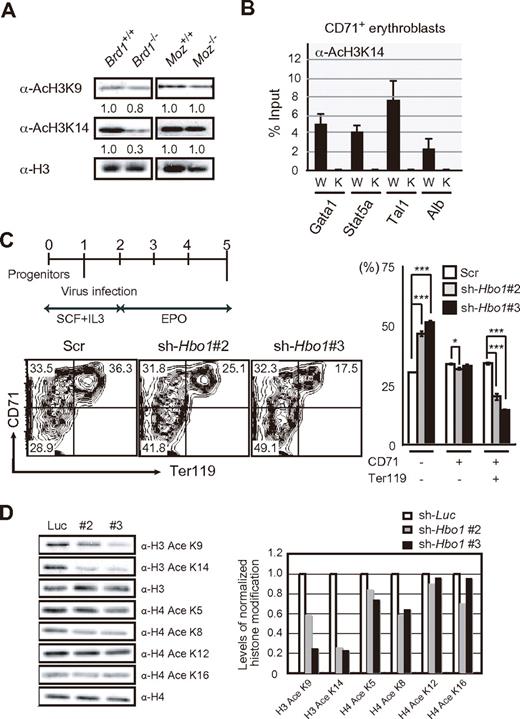

Acetylation of H3K14 is specifically reduced in Brd1−/− mice

To test for a function of Brd1 as a histone modifier, we compared histone acetylation in CD71+Ter119− and CD71+Ter119+ erythroblasts between Brd1−/− and Moz−/− fetal livers. Of note, the level of global acetylation of H3K14 was profoundly decreased in Brd1−/− erythroblasts by 70%-80% and that of H3K9 was also moderately decreased, whereas those of H4K5, K8, and K12 were not significantly changed (Figure 6A and supplemental Figure 6A). In contrast, the levels of global acetylation of H3K9 and H3K14 did not change in Moz−/− erythroblasts (Figure 6A). Similar results were obtained with Brd1−/− and Moz−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and Brd1−/− brain (supplemental Figure 6B-C). In contrast, the levels of representative repressive histone modifications, H3K9me3 and H3K27me3, were not largely changed in erythroblasts and MEFs (supplemental Figure 6D-E). ChIP assays confirmed global reductions in levels of H3K14 acetylation in the promoter regions of both erythroid (Gata1, Stat5a, and Tal1) and nonerythroid (Albumin; Alb) genes (Figure 6B). Furthermore, the ChIP-on-chip analysis in K562 revealed that H3K14 were highly acetylated at the TSS/promoter region of 46.9% of the genes bound by both BRD1 and HBO1, including GATA1, TAL1/SCL, CBFA2T3/ETO2, and STAT5A (supplemental Figure 7). These findings support our biochemical findings that BRD1 forms a HAT complex with HBO1 but not MOZ and imply that this complex is responsible for the bulk of H3K14 acetylation.

The Hbo1-Brd1 complex is responsible for the bulk of H3K14 acetylation. (A) Levels of acetylation at histone H3 in wild-type, Brd1−/−, and Moz−/− CD71+Ter119− erythroblasts. Histones purified from purified CD71+Ter119− erythroblasts were analyzed by Western blotting by use of the indicated antibodies. Levels of acetylated H3K9 and H3K14 were normalized to the amount of H3 and are indicated relative to wild-type control values. (B) Levels of H3K14 acetylation at the promoters of erythroid regulator genes. A ChIP analysis was performed with CD71+ erythroblasts from wild-type (W) and Brd1−/− (K) 12.5 dpc fetal livers with an anti-acetylated H3K14 antibody. The relative amount of immunoprecipitated DNA is depicted as a percentage of input DNA. The data are shown as the mean ± SE for triplicate PCRs. The Alb promoter served as a negative control. (C) Hbo1 knockdown in fetal liver progenitor cells. c-Kit+ CD71− cells were sorted from fetal livers at 12.5 dpc and cultured in the presence of SCF and IL3. Twenty-four hours later, cells were infected with lentiviruses against Hbo1 (#2 and #3) and the culture medium was changed to that containing EPO to induce erythroid differentiation (top left). After a 3-day induction, cells were stained with the indicated antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. The knockdown cells were monitored for expression of GFP, a marker antigen for infection. The flow cytometric profiles of GFP+ cells are indicated (bottom left) and their differentiation defined by the expression of CD71 and Ter119 is shown as the mean ± SE for triplicate cultures (right). * P < .05, *** P < .0005. (D) Levels of acetylation of histones H3 and H4 in Hbo1-knockdown erythroblasts. Histones were prepared from CD71+ erythroblasts purified from the Hbo1-knockdown culture in (C) and analyzed by Western blotting by the use of the indicated antibodies (left). Levels of acetylation of H3 and H4 at each residue were normalized to the amount of H3 and H4, respectively. The acetylation levels relative to the sh-Luc controls are indicated (right).

The Hbo1-Brd1 complex is responsible for the bulk of H3K14 acetylation. (A) Levels of acetylation at histone H3 in wild-type, Brd1−/−, and Moz−/− CD71+Ter119− erythroblasts. Histones purified from purified CD71+Ter119− erythroblasts were analyzed by Western blotting by use of the indicated antibodies. Levels of acetylated H3K9 and H3K14 were normalized to the amount of H3 and are indicated relative to wild-type control values. (B) Levels of H3K14 acetylation at the promoters of erythroid regulator genes. A ChIP analysis was performed with CD71+ erythroblasts from wild-type (W) and Brd1−/− (K) 12.5 dpc fetal livers with an anti-acetylated H3K14 antibody. The relative amount of immunoprecipitated DNA is depicted as a percentage of input DNA. The data are shown as the mean ± SE for triplicate PCRs. The Alb promoter served as a negative control. (C) Hbo1 knockdown in fetal liver progenitor cells. c-Kit+ CD71− cells were sorted from fetal livers at 12.5 dpc and cultured in the presence of SCF and IL3. Twenty-four hours later, cells were infected with lentiviruses against Hbo1 (#2 and #3) and the culture medium was changed to that containing EPO to induce erythroid differentiation (top left). After a 3-day induction, cells were stained with the indicated antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. The knockdown cells were monitored for expression of GFP, a marker antigen for infection. The flow cytometric profiles of GFP+ cells are indicated (bottom left) and their differentiation defined by the expression of CD71 and Ter119 is shown as the mean ± SE for triplicate cultures (right). * P < .05, *** P < .0005. (D) Levels of acetylation of histones H3 and H4 in Hbo1-knockdown erythroblasts. Histones were prepared from CD71+ erythroblasts purified from the Hbo1-knockdown culture in (C) and analyzed by Western blotting by the use of the indicated antibodies (left). Levels of acetylation of H3 and H4 at each residue were normalized to the amount of H3 and H4, respectively. The acetylation levels relative to the sh-Luc controls are indicated (right).

We then tested whether the depletion of HBO1 in erythroblasts recapitulates the defective erythropoiesis of Brd1−/− fetal livers. We purified c-Kit+ CD71− hematopoietic progenitors from 12.5 dpc fetal livers. The cells were transduced with Hbo1 knockdown lentiviruses and then cultured for 3 days in the presence of EPO to induce erythroid differentiation (Figure 6C). Of note, the frequency of CD71+Ter119+ erythroblasts in the green fluorescent protein positive (GFP+) knockdown cells was significantly reduced with sh-Hbo1#2 and #3 (Figure 6C). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the erythroblasts revealed that sh-Hbo1#3 knocked down Hbo1 more efficiently than #2 (#2, 44.7%, and #3, 19.1% of the control). Correspondingly, the block in erythroid differentiation was more pronounced by knockdown with #3. These results indicate that Hbo1 knockdown perturbs differentiation of fetal liver erythroid progenitors in a fashion similar to the absence of Brd1. Importantly, levels of H3K14 acetylation were severely reduced in Hbo1-knockdown erythroblasts and H3K9 acetylation was also significantly reduced (Figure 6D). In addition, levels of H4K5 and K8 acetylation were moderately reduced in Hbo1-knockdown erythroblasts (Figure 6D).

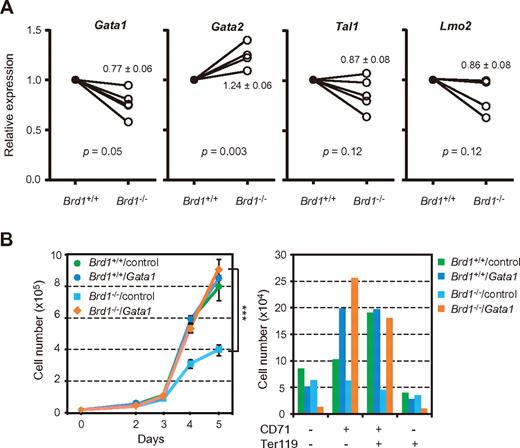

We then compared the expression levels of erythroid transcription factors in wild-type and Brd1−/− erythroblasts by quantitative RT-PCR. As expected, mRNA expression of Gata1, Scl/Tal1, and Lmo2,22-26 erythroid master regulator genes that appeared to be the direct targets of the HBO1-BRD1 complex in K562 cells, was mildly decreased in Brd1−/− erythroblasts (Figure 7A). Furthermore, expression of Gata2, the gene negatively regulated by Gata1,27,28 was up-regulated in Brd1−/− CD71+Ter119+ erythroblasts. These expression patterns implied that the impaired functions of erythroid transcription factors, particularly Gata1, is responsible for the defective erythropoiesis in Brd1−/− fetal livers. To test this hypothesis, we transduced c-Kit+CD71− hematopoietic progenitors from 12.5 dpc fetal livers with Gata1 and cultured them for 3 days in the presence of EPO to induce erythroid differentiation (Figure 7B). Notably, forced expression of Gata1 efficiently restored the proliferative capacity and survival of Brd1−/− erythroblasts (Figure 7B). Of note, however, it only partially canceled the differentiation block at the CD71+Ter119− to CD71+Ter119+ transition (Figure 7B). Furthermore, the morphologic analyses of the purified CD71+Ter119+ erythroblasts revealed no obvious defects in morphologic maturation of Brd1−/− CD71+Ter119+ erythroblasts even in the absence of exogenous Gata1 (supplemental Figure 8). These results suggest that dysregulated expression of Gata1 mainly accounts for impaired proliferation and survival of Brd1−/− erythroblasts.

Insufficient transcription of erythroid regulator genes causes impaired erythropoiesis in Brd1−/− fetal livers. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of expression of erythroid transcription factor genes in erythroblasts purified from wild-type and Brd1−/− 12.5 dpc fetal livers. mRNA levels were normalized to Hprt1 expression. Expression levels relative to those in the wild-type erythroblasts are shown as the mean ± SE (n = 4∼5). (B) Rescue of defective proliferation of Brd1−/− erythroblasts by exogenous Gata1. c-Kit+ CD71− cells were sorted from wild-type (Brd1+/+) and Brd1−/− fetal livers at 12.5 dpc and cultured in the presence of SCF and IL-3. Twenty-four hours later, cells were infected with either GFP control or Gata1 retroviruses and the culture medium was changed to that containing EPO to induce erythroid differentiation. After a 3-day induction, cells were stained with the indicated antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. Cell growth during culture (left) and the final numbers of erythroid cells at different stages of differentiation (CD71−Ter119− to CD71−Te119+; right) are shown as mean ± SE for triplicate cultures. ***P < .0005.

Insufficient transcription of erythroid regulator genes causes impaired erythropoiesis in Brd1−/− fetal livers. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of expression of erythroid transcription factor genes in erythroblasts purified from wild-type and Brd1−/− 12.5 dpc fetal livers. mRNA levels were normalized to Hprt1 expression. Expression levels relative to those in the wild-type erythroblasts are shown as the mean ± SE (n = 4∼5). (B) Rescue of defective proliferation of Brd1−/− erythroblasts by exogenous Gata1. c-Kit+ CD71− cells were sorted from wild-type (Brd1+/+) and Brd1−/− fetal livers at 12.5 dpc and cultured in the presence of SCF and IL-3. Twenty-four hours later, cells were infected with either GFP control or Gata1 retroviruses and the culture medium was changed to that containing EPO to induce erythroid differentiation. After a 3-day induction, cells were stained with the indicated antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. Cell growth during culture (left) and the final numbers of erythroid cells at different stages of differentiation (CD71−Ter119− to CD71−Te119+; right) are shown as mean ± SE for triplicate cultures. ***P < .0005.

Discussion

In this study, we identified a novel HAT complex consisting of HBO1, BRD1, and ING4. BRD1 was believed to be involved in the MOZ HAT complex on the basis of analogy to BRPF13,4 but appeared to prefer to form a complex with HBO1. The finding that HBO1 stabilized the BRD1 protein further supported the physiologic significance of this complex. The levels of H3K14 acetylation were profoundly reduced in all cells and organs examined in Brd1−/− mice and Hbo1-knockdown erythroblasts. Thus, this complex is responsible for the bulk of H3K14 acetylation in general. Very recently, loss of Hbo1 in mice was reported to lead to a significant reduction of H3K14 acetylation, but not to affect acetylation at other histone residues.29 These observations correspond well to ours and support our notion that BRD1 functions in the HBO1 HAT complex. However, residual H3K14 acetylation was evident in Brd1−/− cells, suggesting the existence of other H3K14 HATs. These might include the Moz-Brpf1 complex, which reportedly acetylates H3K9 and K14,7,30 although the levels of H3 acetylation were not affected in Moz−/− erythroblasts or MEFs in this study. In addition, another Hbo1 HAT complex, which involves Jade family proteins,3,20 might also contribute to the acetylation of H3K14, although its capacity to acetylate H3K14 has not been tested. This notion is supported by the finding that Hbo1 knockdown affected levels of H3K14 acetylation more severely than the depletion of Brd1 in erythroblasts.

HBO1 and MOZ/MORF MYST HAT complexes target chromatin via multiple PHD finger-based interactions with histone H3 tails.5 The PHD finger of ING4 recognizes and binds to H3K4me3.5-7 JADE and BRPF family proteins share 2 highly conserved PHD fingers that function in chromatin binding. Given their similar composition, the HBO1 and MOZ/MORF HAT complexes likely regulate acetylation of H3K14. Nonetheless, the absence of Brd1 had little or no impact on the acetylation of H3K9 and H4 (K5, K8, and K12) whereas Hbo1 knockdown considerably affected the acetylation of H3K9 and H3K14 and marginally reduced levels of acetylated H4K5 and K8. Jade1L knockdown reportedly decreased bulk histone H4 acetylation in 293T cells.20 These findings highlight differences in specificity among these HAT complexes.

HBO1 was originally cloned as a binding partner of origin recognition complex 1, a subunit of the DNA replication initiation complex, and interacts with MCM2, a component of the MCM helicase complex.31,32 According to accumulating evidence,3,33,34 HBO1 has a crucial role in regulation of the prereplicative complex assembly and initiation of DNA replication. In contrast, recent findings also unveiled its role in transcriptional regulation, sometimes in concert with transcription factors. Two closely related HBO1 complexes with different ING proteins (either ING4 or ING5) have been characterized and MCM proteins were specifically copurified with the ING5-HBO1 complex, suggesting that the ING5 complex functions in DNA replication whereas the ING4 complex is involved in transcriptional regulation. Actually, ING5 knockdown in 293T cells completely blocks cell-cycle progression through the S phase.3 Thus, composition, ie, the recruitment of either ING4 or ING5, may hold the key to context-dependent function of HBO1. BRD1 forms a complex with HBO1 and ING4 and loss of Brd1 impaired the maturation and/or survival of erythroblasts, but not their proliferation, indicating that the transcription-related function of Hbo1 is mainly affected in Brd1-deficient erythroid cells. However, Kueh et al29 observed no defects in DNA replication or cell proliferation in Hbo1 mutant embryos, MEFs, or immortalized fibroblasts. Role of Hbo1 in DNA replication might require careful reevaluation using Hbo1-deficient cells.

It is widely recognized that the N-terminal tail of histone proteins is acetylated in the promoter region of actively transcribed genes and acetyl-lysine residues are recognized by bromodomain-containing factors in general. Although the role of acetylation at H3K9 and K14 is not well understood compared with that of histone methylation, H4K8 and K12 acetylation is reportedly followed by H3K9 and K14 acetylation at the IFNβ promoter after a viral infection.35 In this cascade, H4K8 acetylation mediates recruitment of the SWI/SNF complex via the bromodomain-containing BRG1 subunit, whereas the acetylation of H3K9 and K14 is critical to the recruitment of TFIID via a tandem bromodomain factor, TAFII250. This coordinated recruitment of transcriptional complexes participates in the transcriptional induction of the IFN-β gene. However, the BAF complex is reported to be anchored to promoters by acetylated H3K14 though the BAF57 subunit, which contains a bromodomain.36 Therefore, the BRD1-HBO1 complex might be involved in the recruitment of transcriptional complexes to promoters via H3K14 acetylation and exert activity in transcriptional initiation. However, the binding of BRD1 and HBO1 was detected throughout the coding regions of genes, although the peaks were detected around TSS. Therefore, we cannot eliminate a role for the HBO1 HAT complex in transcriptional elongation as proposed by Saksouk et al.6 The recognition of H3K36me3, an epigenetic mark for transcriptional elongation, by the PWWP domain of Brpf1 supports this notion.37

Among the study of various developmental defects observed in Brd1−/− embryos, detailed analyses of erythropoiesis highlighted a crucial role for the HBO1-BRD1 complex in transcriptional activation of developmental regulator genes. The process of erythropoiesis is well orchestrated at the molecular level by a complex network of transcription factors, including Gata1, Gata2, and Scl/Tal1.24,26 A genome-wide ChIP-chip analysis clearly demonstrated that the HBO1-BRD1 complex targets genes involved in “transcriptional regulation,” including these key erythroid regulator genes. Among them, the transcription factor gene Gata1 is required for terminal erythroid maturation and functions as an activator or repressor depending on context. Gata1-deficient embryos are severely anemic and their fetal liver erythroblasts have a differentiation block at the CD71+Ter119− stage and undergo massive apoptosis.22-24,26 Although the reduction in Gata1 expression was mild in Brd1−/− erythroblasts, the expression of Gata2, an erythroid regulator gene negatively regulated by Gata1, was mildly but significantly derepressed, and impaired Brd1−/− erythropoiesis was partially restored by the expression of Gata1. Given that the Hbo1-Brd1 complex regulates global H3K14 acetylation in erythroblasts, the defective erythropoiesis could not be attributed solely to Gata1. The failure of exogenous Gata1 to release differentiation block of Brd1−/− erythroblasts supports this notion. Nevertheless, all these findings provide the first evidence of a crucial role for the HBO1-BRD1-ING4 complex and H3K14 acetylation in the transcriptional activation of key developmental regulator genes required for development and differentiation.

The MYST family HATs are involved in various aspects of tumorigenesis as transcriptional regulators.1 Overexpression of HBO1 has also been reported in various human cancers.38 Intriguingly, BRD1 fused to PAX5 (PAX5-BRD1) has recently been implicated in acute lymphoblastic leukemia.39 This fusion protein is thought to ectopically activate transcription of PAX5 target genes by recruiting HBO1. Thus, our findings also provide a molecular basis to understanding the complex functions of HBO1 in cancer.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Drs Masayoshi Iizuka and Matthias Hammerschmidt for providing the pFLAG-HBO1 and pcDNA3-Flag-Brpf1 vectors, respectively; Makiko Yui for her technical assistance; and Drs Kiyotaka Toshimori and Tohru Mutoh for technical advice on the histochemical analyses.

This work was supported in part by MEXT KAKENHI (22118004, 20052009, 21790906, and 22118004) and for the Global COE Program (Global Center for Education and Research in Immune System Regulation and Treatment), MEXT, Japan, a Grant-in-Aid for the Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (CREST) from the Japan Science and Technology Corporation (JST), and a grant from the Takeda Science Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: Y.M., S.M., and A.S. performed the experiments, analyzed results, made the figures, and wrote the manuscript; M.N. cloned Brd1 cDNA; M.E., T.A.E., and T.T. performed the ChIP-chip assay; J.S. and H.K. generated Brd1-deficient mice; T.K. and I.K. provided Moz-deficient mice and prepared Moz-deficient MEFs; T.C. performed phenotypic analysis of Brd1-deficient mice; N.Y. gave a critical suggestion to the project; and A.I. conceived of and directed the project, secured funding, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Atsushi Iwama, MD, PhD, 1-8-1 Inohana, Chuo-ku, Chiba, 260-8670 Japan; e-mail: aiwama@faculty.chiba-u.jp.

References

Author notes

Y.M., S.M., and A.S. contributed equally to this work.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal