Abstract

The BCR-ABL fusion protein generated by t(9;22)(q34;q11) in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) plays an essential role in the pathogenesis of the myeloproliferative disorder status at the chronic phase of the disease, but progression from the chronic phase to blast crisis (BC) is believed to require additional mutations. To explore the underlying mechanisms for BC, which is characterized by a blockage of blood cell differentiation, we screened several genes crucial to hematopoiesis and identified 10 types of mutations in RUNX1 among 11 of 85 (12.9%) patients with acute transformation of CML. Most of the mutations occurred in the runt homology domain, including H78Q, W79C, R139G, D171G, R174Q, L71fs-ter94, and V91fs-ter94. Further studies indicated that RUNX1 mutants not only exhibited decreased transactivation activity but also had an inhibitory effect on the WT RUNX1. To investigate the leukemogenic effect of mutated RUNX1, H78Q and V91fs-ter94 were transduced into 32D cells or BCR-ABL–harboring murine cells, respectively. Consistent with the myeloblastic features of advanced CML patients with RUNX1 mutations, H78Q and V91fs-ter94 disturbed myeloid differentiation and induced a BC or accelerated phase–like phenotype in mice. These results suggest that RUNX1 abnormalities may promote acute myeloid leukemic transformation in a subset of CML patients.

Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a clonal myeloproliferative disorder of the hematopoietic stem cells that typically progresses from a relatively benign chronic phase (CP), which is characterized by massive accumulation of mature granulocytes, to an accelerated phase (AP), and ultimately into terminal blast crisis (BC), which resembles acute leukemia characterized by the rapid expansion of myeloid or lymphoid blasts resulting from a blockage of cell differentiation. Disease progression can usually be blocked or slowed down by tyrosine kinase inhibition therapy or allogeneic transplantation. Survival outcomes plummet from CP (80%) to AP (50%) and then to BC (20%), indicating that current therapies work much better in CP than in AP or BC.1-3 Therefore, it is important to clarify the mechanism of BC with an emphasis on those genes or pathways which may be future targets for predictive markers or treatment of CML progression.

Greater than 95% of CML cases are associated with the presence of the hallmark chromosomal translocation t(9;22)(q34;q11) (ie, the Philadelphia or Ph chromosome).4 A large body of evidence has suggested that the initial event in CML pathogenesis is the acquisition of BCR-ABL, which causes not only a substantial expansion of terminally differentiated neutrophils, but also an instability of the genome.5 Progression to BC is accompanied by a severe blockage in hematopoietic cell differentiation and is thought to require additional mutations other than BCR-ABL. Additional genetic abnormalities have been reported to be associated with CML progression, including chromosomal changes such as a “double” Ph chromosome, isochromosome i(17q), trisomy 8, trisomy 19, loss of chromosome 9, t(3;21)(q26;q22) generating RUNX1/MDS1/EVI1, t(7;11)(p15;p15) generating NUP98/HOXA9, and mutations in tumor-suppressor genes such as p53, INK4A/ARF, and RB.5,6 Coexpression of RUNX1/MDS1/EVI1 or NUP98/HOXA9 with BCR-ABL can block myeloid differentiation and induce an acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in mice, suggesting that the induction of AML involves cooperation between mutations that dysregulate protein tyrosine kinase signaling and those that disrupt hematopoietic transcriptional regulation.7,8

The RUNX1 gene, a transcription factor (TF) located on chromosome 21q22, encodes the major α-subunit of the heterodimeric core binding factor (CBF) complex, which consists of the interacting RUNX1 and the β-subunit of CBF (CBFβ)9 and has been shown to be essential for normal hematopoiesis. Both RUNX1 and CBFβ are among the most frequent targets in leukemia through chromosomal translocations or gene mutations.10,11 With regard to the RUNX1 gene, different chromosomal translocations have been reported in human acute leukemias such as t(8;21)(q22;q22) generating the RUNX1-ETO fusion gene, t(12;21)(p12;q22) generating the TEL-RUNX1 fusion transcript, and the t(3,21)(q26;q22) generating the RUNX1/MDS1/EVI1 fusion gene. The RUNX1 protein contains, from N-terminal to C-terminal, 3 main domains: the conserved runt homology domain (RHD), the transcriptional activation domain (TAD), and the transcription repression domain (TRD).12 RUNX1 abnormalities have also been identified in some cases of secondary myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), de novo AML, and treatment-related AML with acquired trisomy 21.10,13,14 RUNX1 mutations were found in 5 of 18 patients with advanced CML presenting with acquired trisomy 21.15 Recently, Grossmann et al reported a high incidence of RUNX1 mutations in CML-BC.16 However, the clinical significance of the RUNX1 mutations in advanced CML needs to be further explored with data from more populations and through in-depth biologic investigation. To evaluate the role of RUNX1 mutations as an additional genetic event in the pathogenesis of acute transformation of CML, we analyzed the entire coding region of the RUNX1 gene in a large cohort of Chinese CML-AP/BC patients (N = 85) with distinct AML subtype harboring BCR-ABL, and addressed the leukemogenic potential of these mutations. Interestingly, coexpression of BCR-ABL and 2 representative RUNX1 mutants resulted in the myeloid progenitors acquiring unusual growth advantages in vitro and induced the AML phenotype in mice. Our results indicate that RUNX1 abnormalities might be closely correlated with BC/AP progression in a subset of CML patients.

Methods

Patients

Clinical information for the patients in the study was described previously.17 Retrospectively, 85 advanced CML patients (n = 28 CML-AP and n = 57 CML-BC patients) were examined. Criteria for AP were 10%-20% blast cells in the BM, thrombocytopenia, and resistance to therapy; for BC, they were ≥ 20% blasts in the blood or BM with extramedullary blast infiltrates.

Sequencing of cDNA and genomic DNA of the RUNX1 gene

Experiments screening for RUNX1 mutations were as described previously.17

Plasmid constructions

The retroviral vectors murine stem cell virus (MSCV)–internal ribosome entry site (IRES)–green fluorescent protein (GFP) and MSCV-BCR-ABL-IRES-GFP were kindly provided by Dr Warren S. Pear (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA). The MSCV-IRES-yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) vector was constructed as described previously.18 cDNAs containing full-length wild-type (WT) or mutated RUNX1 were obtained by RT-PCR on BM samples. The integrity of the amplified sequences was confirmed by DNA sequencing. Whereas EcoRI and BglII were used for molecular cloning of different RUNX1 sequences into the pflag-CMV-4 expression vector (Sigma-Aldrich), EcoRI and XhoI were used to clone these sequences into the pcDNA3.1/myc-His(-)B vector (Invitrogen), the MSCV-IRES-YFP vector, or the MSCV-IRES-GFP vector, respectively. The entire coding region of CBFβ was subcloned into the pflag-CMV-4 expression vector. A reporter plasmid containing an M-CSF receptor (M-CSFR) promoter (pM-CSF-R-luc) was used to conduct the relevant experiments as described previously.17

Cell culture

Cells (293T and NIH 3T3) were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (Biochrom). The murine myeloid progenitor 32Dcl3 cell line (32D cells) was grown in RPMI medium 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, L-glutamine, antibiotics, and 20 ng/mL of murine IL-3 (R&D Systems).

Subcellular localization

Cells (293T) were cultured in 6-well plates containing 12-mm round coverslips (104 cells/well). The full-length cDNAs of WT and RUNX1 mutants were cloned into expression vector pcDNA3.1. These constructs were transfected into the 293T cells using the calcium phosphate (Promega) transfection method. The expressed RUNX1 proteins were immunostained with anti-RUNX1 Ab (Cell Signaling Technology) and Rhodamine Red-X-AffiniPure goat anti–rabbit IgG (H+L; Jackson ImmunoResearch), and the nucleus were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Vector Laboratories) and analyzed on a confocal microscope. Cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts were also analyzed by Western blot (WB).

ChIP-qPCR

ChIP was carried out using the ChIP Assay Kit (Millipore) according to the manufacturer's protocol with anti-RUNX1 Ab (Cell Signaling Technology). The immunoprecipitated chromatin from WT or mutated RUNX1 transduced 32D cells was detected in triplicate by real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) using the indicated probes (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). The levels of enrichment of each promoter by the indicated RUNX1 proteins were analyzed according to the method recommended by the ChampionChIP qPCR Primers manufacturer (SABiosciences).

Gel-filtration study

Nuclear extracts from 293T cells cotransfected with expression plasmids encoding myc-RUNX1-WT and flag-RUNX1 mutants were analyzed by gel filtration using an ÄKTAxpress MAb system with a Superdex 200 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare). Collected fractions were analyzed by WB analysis using anti-myc Ab (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

CoIP

For coimmunoprecipitation (CoIP), 10 μg of different myc-RUNX1–expressing plasmids was cotransfected with 10 μg of flag-CBFβ–expressing plasmid into 293T cells. Whole-cell lysate extracted with RIPA buffer (Beyotime) after 48 hours was immunoprecipitated by anti-flag M2 beads (Sigma-Aldrich) using a standard protocol. The Abs used for WB were anti-flag (M2) Ab (Sigma-Aldrich), anti-myc Ab (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-CBFβ polyclonal Ab (Abcam).

Gel-shift assay

Retroviral transduction and generation of stable cell lines

32D cells were infected by retroviral supernatants harboring WT RUNX1 or mutant in culture medium supplemented with polybrene (8 μg/mL; Millipore). GFP+ cells were isolated by flow cytometry after 48 hours and sorted again after 2 weeks to generate stable cell lines expressing the GFP and RUNX1 proteins.

Differentiation assay, colony-forming assay, semiquantitative RT-PCR, and growth kinetics assay in 32D cells

The G-CSF (R&D Systems)–induced 32D cell differentiation experiments and colony-forming assay were carried out as described previously.21 For detection of murine myeloperoxidase (MPO), lactoferrin (LF), and β-actin, semi-quantitative RT-PCR was performed as described previously.22 To investigate the growth kinetics of 32D cells in the G-CSF treatment and after withdrawal of G-CSF, growth curves were generated by counting viable cells.

Retroviral preparations, BM transplantation, and hematopathologic analysis in mice

Retroviral supernatants were generated, and BM transplantation was performed as described previously.17 Hematopathologic analysis and flow cytometric immunophenotyping were performed as described previously.18 Cumulative probability of survival after BM transplantation was presented in a Kaplan-Meier format using Prism Version 5 software (GraphPad). To assess whether the primary leukemic cells were transplantable, 5 × 105 cells were injected into the tail veins of sublethally irradiated (400 cGy) secondary recipient mice. All animal experiments were approved by the Department of Animal Experimentation at Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine.

Results

High frequency of RUNX1 mutations in CML patients with acute transformation

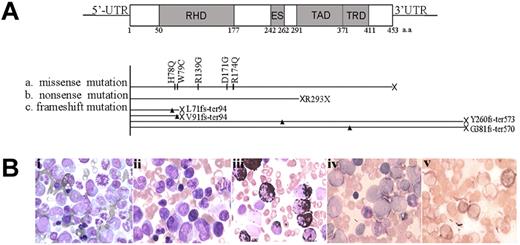

The RUNX1 gene was found to be mutated in 11 of 85 (12.9%) patients with CML acute transformation (28 AP and 57 BC) by sequencing both cDNA and genomic DNA of the whole RUNX1 gene (Figure 1A and Table 1) and eliminating single-nucleotide polymorphisms by screening 200 normal controls. No mutation was detected in these patients during CML-CP, indicating that the RUNX1 mutation is correlated with acute transformation of CML. All of the RUNX1 mutations were heterozygous, with the other allele still being WT in these 11 patients. In total, 10 types of mutations, 5 missense mutations (H78Q, W79C, R139G, D171G, and R174Q), 2 truncated mutations (L71fs-ter94 and V91fs-ter94) in the N-terminal region, 1 nonsense (R293X) and 2 elongation-frameshift mutations (Y260fs-ter573 and G381fs-ter570) in the C-terminal region were identified (Figure 1A). The most frequently detected mutations were located at RHD, including all 5 missense mutations and 2 truncated mutations. The 11 patients with RUNX1 mutations were all characterized by an acute myeloblastic transformation morphology (Figure 1B).

RUNX1 mutations in myeloid transformation of CML. (A) Summary of the 10 types of RUNX1 mutations in CML patients with acute transformation of CML analyzed in our study. Three categories of mutations were seen: missense mutations, nonsense mutations, and frameshift mutations. Arrowheads and vertical lines indicate the sites of mutation; X represents the site of the stop codon. ES indicates the Ear-2 binding site; UTR, untranslated region. (B) Morphological and histochemical investigation of BM samples from unique patient number 2 (UPN2) with RUNX1 H78Q. (Bi) Wright staining of BM cellular smear from patient UPN2 at CML-CP. (Bii-Bv) Examination on the BM samples from patient UPN2 at CML-BC: Wright staining (Bii); MPO staining, a specific marker of myeloid cells (Biii); periodic acid-Schiff staining (Biv); and naphthol AS-chloracetate esterase staining, a marker of granulocytes (Bv).

RUNX1 mutations in myeloid transformation of CML. (A) Summary of the 10 types of RUNX1 mutations in CML patients with acute transformation of CML analyzed in our study. Three categories of mutations were seen: missense mutations, nonsense mutations, and frameshift mutations. Arrowheads and vertical lines indicate the sites of mutation; X represents the site of the stop codon. ES indicates the Ear-2 binding site; UTR, untranslated region. (B) Morphological and histochemical investigation of BM samples from unique patient number 2 (UPN2) with RUNX1 H78Q. (Bi) Wright staining of BM cellular smear from patient UPN2 at CML-CP. (Bii-Bv) Examination on the BM samples from patient UPN2 at CML-BC: Wright staining (Bii); MPO staining, a specific marker of myeloid cells (Biii); periodic acid-Schiff staining (Biv); and naphthol AS-chloracetate esterase staining, a marker of granulocytes (Bv).

Main clinical and biological features of CML-AP/BC patients with RUNX1 mutations

| UPN . | Sex/age, y . | RUNX1 mutations . | CP . | AP/BC . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bp change . | aa change . | Karyotype . | BCR-ABL subtype . | Karyotype . | BM examinations: myeloblasts + promyelocytes . | ||

| 1 | F/57 | 211 del C | L71fs-ter94 | NA | b2a2 | 46, XX, t(2;12), t(9;22)(q34;q11) [6]/46, XX, t(9;22)(q34;q11) [3]/[10] | 24% |

| 2 | M/42 | 234 C > A | H78Q | 46, XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11) | b2a2 | 51–55, XY, 2t(9;22)(q34;q11) [cp11] | 69% |

| 3 | F/18 | 237 G > C | W79C | NA | b2a2 | 46, XX, t(9;22)(q34;q11) [6]/[10] | 20% |

| 4 | M/28 | 415 C > G | R139G | 46, XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11) | b2a2 | 46, XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11) [3]/45, XY, -11, t(9;22)(q34;q11) [4]/[10] | 91% |

| 5 | M/23 | 512 A > G | D171G | NA | b3a2 | 46, XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11) [6]/[10] | 64% |

| 6 | M/54 | 521 G > A | R174Q | NA | b2a2 | 46, XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11) [2]/[5] | 52% |

| 7 | F/39 | 521 G > A | R174Q | NA | b2a2 | NA | 72% |

| 8 | M/64 | 877 C > T | R293X | 46, XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11) | b3a2 | 46, XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11) [3]/[4] | 92% |

| 9 | M/45 | 775-778dupCAAT | Y260fs-ter573 | 46, XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11) | b3a2 | 46, XY, -5, +8, t(9;22)(q34;q11) [2]/46, XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11)[1]/[4] | 34% |

| 10 | M/43 | 271 del G | V91fs-ter94 | 46, XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11) | b3a2 | NA | 76% |

| 11 | M/41 | 1140-1144 del CGGCG | G381fs-ter570 | 46, XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11) | b3a2 | 46, XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11) [6]/[10] | 38% |

| UPN . | Sex/age, y . | RUNX1 mutations . | CP . | AP/BC . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bp change . | aa change . | Karyotype . | BCR-ABL subtype . | Karyotype . | BM examinations: myeloblasts + promyelocytes . | ||

| 1 | F/57 | 211 del C | L71fs-ter94 | NA | b2a2 | 46, XX, t(2;12), t(9;22)(q34;q11) [6]/46, XX, t(9;22)(q34;q11) [3]/[10] | 24% |

| 2 | M/42 | 234 C > A | H78Q | 46, XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11) | b2a2 | 51–55, XY, 2t(9;22)(q34;q11) [cp11] | 69% |

| 3 | F/18 | 237 G > C | W79C | NA | b2a2 | 46, XX, t(9;22)(q34;q11) [6]/[10] | 20% |

| 4 | M/28 | 415 C > G | R139G | 46, XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11) | b2a2 | 46, XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11) [3]/45, XY, -11, t(9;22)(q34;q11) [4]/[10] | 91% |

| 5 | M/23 | 512 A > G | D171G | NA | b3a2 | 46, XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11) [6]/[10] | 64% |

| 6 | M/54 | 521 G > A | R174Q | NA | b2a2 | 46, XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11) [2]/[5] | 52% |

| 7 | F/39 | 521 G > A | R174Q | NA | b2a2 | NA | 72% |

| 8 | M/64 | 877 C > T | R293X | 46, XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11) | b3a2 | 46, XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11) [3]/[4] | 92% |

| 9 | M/45 | 775-778dupCAAT | Y260fs-ter573 | 46, XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11) | b3a2 | 46, XY, -5, +8, t(9;22)(q34;q11) [2]/46, XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11)[1]/[4] | 34% |

| 10 | M/43 | 271 del G | V91fs-ter94 | 46, XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11) | b3a2 | NA | 76% |

| 11 | M/41 | 1140-1144 del CGGCG | G381fs-ter570 | 46, XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11) | b3a2 | 46, XY, t(9;22)(q34;q11) [6]/[10] | 38% |

NA indicates not available; del, deletion; b2a2, exon13 of BCR fused with exon2 of ABL; b3a2, exon14 of BCR fused with exon2 of ABL; and cp, composite karyotype.

Subcellular localization of WT and mutated RUNX1

Previous studies have indicated that RHD (residues 50-177), nuclear localization signal (residues 167-183), and nuclear matrix targeting signal (residues 351-381) are important for the punctuate subnuclear distribution of the RUNX1 protein.12 To investigate the subcellular localization of the mutated RUNX1 (Figure 2A), we performed immunostaining experiments using anti-RUNX1 Ab. We found that some RUNX1 mutants, including D171G in RHD, R293X in TAD, and G381fs-ter570 in TRD, were evenly localized in the nucleus, similar to WT RUNX1; others, such as H78Q and R174Q in the RHD, presented nuclear speckle distribution; and still others, such as V91fs-ter94 and R139G, showed a weakened nuclear localization concomitant with an increased cytoplasmic distribution (Figure 2B). These results are consistent with a previous study showing that nuclear localization of the RUNX1 product critically depends on the integrity of the RHD.23 To further confirm the subcellular localization of WT and mutated RUNX1, we examined RUNX1 protein expression in cellular nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts, respectively. As shown in Figure 2C, the mutant proteins V91fs-ter94 and R139G were detected in both the nuclear and cytosolic fractions, whereas WT RUNX1 and the other mutants were exclusively detected in nuclear protein extracts.

Subcellular localization of the WT and mutated RUNX1 proteins. (A) Schematic representation of RUNX1 showing location of functional domains and specific RUNX1 mutations used in our study. Horizontal bars indicate RUNX1 (453 aa), including the RHD domain (50-177 aa), the ES domain (242-262 aa), the TAD domain (291-371 aa), and the TRD domain (371-411 aa). The numbers in the left column indicate the unique patient numbers (UPN2, UPN4-UPN8, UPN10, and UPN11) described in Table 1. Mutant no. in the right column indicates the number of mutants. (B) Subcellular localization of the indicated RUNX1 proteins was visualized by confocal microscopy analysis in the 293T cell line. Left panels show the merged images; middle panels, localization patterns of WT RUNX1 or mutants; and the right panels show nuclei as visualized by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining. (C) Expression patterns of RUNX1 mutant proteins in the 293T cell line. A total of 2 × 106 cells for each mutant were used for stepwise separation of cytoplasmic and nuclear extraction, and extracted proteins from an equivalent of 4 × 105 cells per fraction were used for WB. An Ab against RUNX1 was used to detect the exogenously expressed RUNX1 proteins. The 2 different gels are indicated by the gray dividing lines; n indicates nuclear protein extraction; and c, cytoplasmic protein extraction.

Subcellular localization of the WT and mutated RUNX1 proteins. (A) Schematic representation of RUNX1 showing location of functional domains and specific RUNX1 mutations used in our study. Horizontal bars indicate RUNX1 (453 aa), including the RHD domain (50-177 aa), the ES domain (242-262 aa), the TAD domain (291-371 aa), and the TRD domain (371-411 aa). The numbers in the left column indicate the unique patient numbers (UPN2, UPN4-UPN8, UPN10, and UPN11) described in Table 1. Mutant no. in the right column indicates the number of mutants. (B) Subcellular localization of the indicated RUNX1 proteins was visualized by confocal microscopy analysis in the 293T cell line. Left panels show the merged images; middle panels, localization patterns of WT RUNX1 or mutants; and the right panels show nuclei as visualized by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining. (C) Expression patterns of RUNX1 mutant proteins in the 293T cell line. A total of 2 × 106 cells for each mutant were used for stepwise separation of cytoplasmic and nuclear extraction, and extracted proteins from an equivalent of 4 × 105 cells per fraction were used for WB. An Ab against RUNX1 was used to detect the exogenously expressed RUNX1 proteins. The 2 different gels are indicated by the gray dividing lines; n indicates nuclear protein extraction; and c, cytoplasmic protein extraction.

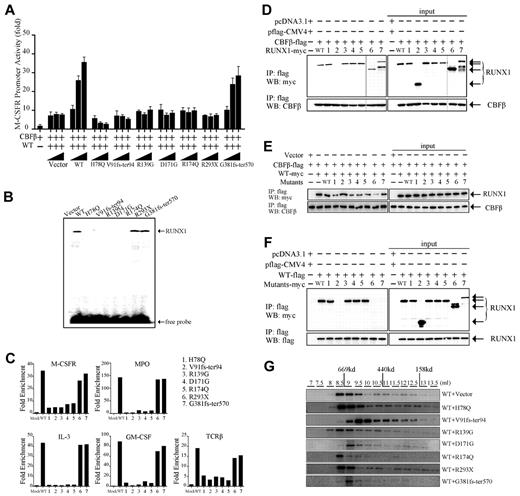

Transregulatory activities of RUNX1 mutants

Because RUNX1 is a key TF in the regulation of normal hematopoiesis,24,25 we determined the transregulatory activities of its mutants using an M-CSFR promoter–containing RUNX1 response element–coupled luciferase reporter. A previous study indicated that CBFβ alone could not induce the transactivation of the promoter of M-CSFR.26 In contrast, when WT RUNX1 and CBFβ were cotransfected into 293T cells, the activation potential was induced 10-fold higher compared with CBFβ alone. None of the mutants induced significant transactivation except G381fs-ter570 (supplemental Figure 1A). We also investigated whether RUNX1 mutants could act as dominant-negative inhibitors of WT RUNX1. Unlike WT RUNX1, which transactivated the M-CSFR promoter in a dose-dependent manner, RUNX1 mutants, including H78Q, V91fs-ter94, R139G, D171G, R174Q, and R293X, could affect the reporter activities and abrogate the dose-dependent increase of transactivation of WT RUNX1 when cotransfected with WT RUNX1 (Figure 3A and supplemental Figure 1B). Interestingly, the RUNX1-H78Q and V91fs-ter94 mutants even suppressed the basal transactivation activity of WT RUNX1 (Figure 3A). As expected, the G381fs-ter570 mutant induced the transactivation activity similarly to WT RUNX1.

Functional analysis of RUNX1 mutants in vitro. (A) Transcriptional potential of the RUNX1 mutants in 293T cells. Cells were cotransfected with 0.5 μg of pM-CSF-R-luc reporter plasmid, 0.5 μg of flag-CBFβ expression plasmid, the indicated amount of RUNX1 expression plasmid, and 0.05 μg of pRL-SV40 as an internal control. The myc-WT RUNX1–encoding plasmid (0.5 μg) was cotransfected with increasing doses (0.5, 1, and 1.5 μg) of expression vectors containing the indicated RUNX1 mutants. Each value represents the mean of 3 independent experiments. The relative luciferase units are expressed as average ± SD. (B) DNA-binding potential of RUNX1 mutants analyzed by gel-shift assay using nuclear extracts from 293T cells transfected with WT or mutated RUNX1 expression plasmids. (C) ChIP-qPCR assay of the IL-3, GM-CSF, M-CSFR, MPO, and TCRβ promoters in 32D cells. WT RUNX1 and G381fs-ter570 proteins, but not H78Q, V91fs-ter94, R139G, D171G, R174Q, or R293X mutant proteins, were enriched on these promoters. (D) Heterodimerization ability of RUNX1 mutants with CBFβ. 293T cells were transfected transiently with flag-CBFβ together with myc-WT RUNX1 or mutants. Upper panel shows that the immunoprecipitation of whole-cell lysates by anti-flag Abs coprecipitates the indicated myc-RUNX1 proteins; bottom panel shows the corresponding CBFβ expression levels analyzed by anti-CBFβ Ab. The numbers (1-7) represent various RUNX1 mutants that are also shown in panel C and in Figure 2A. The 2 different gels are indicated by the gray dividing lines. (E) RUNX1 mutants compete with WT to bind CBFβ. Ectopic expression of RUNX1 mutants could impair the interaction between WT RUNX1 and CBFβ. 293T cells were transfected with flag-CBFβ and myc-tagged WT RUNX1 or with RUNX1 mutants. After 48 hours, the proteins were prepared for anti-flag immunoprecipitation, followed by WB with anti-flag and anti-myc Abs. H78Q, R139G, D171G, R174Q, and G381fs-ter570, especially R293X, but not V91fs-ter94, could compete with WT to bind CBFβ. (F) Interaction between WT and mutated RUNX1 proteins. 293T cells were transiently transfected with flag-RUNX1 together with myc-WT RUNX1 or mutants. After 48 hours, whole-cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-flag Ab and analyzed by WB with anti-myc (top panel) and anti-flag (bottom panel) Abs. Flag-RUNX1 efficiently interacts with myc-WT RUNX1, H78Q, R139G, D171G, and R174Q, but not with V91fs-ter94, R293X, or G381fs-ter570. (G) Gel-filtration analysis. Protein fractions collected from the indicated elution volumes were analyzed by WB using anti-myc Ab. Vertical lines show the positions of the corresponding size standards.

Functional analysis of RUNX1 mutants in vitro. (A) Transcriptional potential of the RUNX1 mutants in 293T cells. Cells were cotransfected with 0.5 μg of pM-CSF-R-luc reporter plasmid, 0.5 μg of flag-CBFβ expression plasmid, the indicated amount of RUNX1 expression plasmid, and 0.05 μg of pRL-SV40 as an internal control. The myc-WT RUNX1–encoding plasmid (0.5 μg) was cotransfected with increasing doses (0.5, 1, and 1.5 μg) of expression vectors containing the indicated RUNX1 mutants. Each value represents the mean of 3 independent experiments. The relative luciferase units are expressed as average ± SD. (B) DNA-binding potential of RUNX1 mutants analyzed by gel-shift assay using nuclear extracts from 293T cells transfected with WT or mutated RUNX1 expression plasmids. (C) ChIP-qPCR assay of the IL-3, GM-CSF, M-CSFR, MPO, and TCRβ promoters in 32D cells. WT RUNX1 and G381fs-ter570 proteins, but not H78Q, V91fs-ter94, R139G, D171G, R174Q, or R293X mutant proteins, were enriched on these promoters. (D) Heterodimerization ability of RUNX1 mutants with CBFβ. 293T cells were transfected transiently with flag-CBFβ together with myc-WT RUNX1 or mutants. Upper panel shows that the immunoprecipitation of whole-cell lysates by anti-flag Abs coprecipitates the indicated myc-RUNX1 proteins; bottom panel shows the corresponding CBFβ expression levels analyzed by anti-CBFβ Ab. The numbers (1-7) represent various RUNX1 mutants that are also shown in panel C and in Figure 2A. The 2 different gels are indicated by the gray dividing lines. (E) RUNX1 mutants compete with WT to bind CBFβ. Ectopic expression of RUNX1 mutants could impair the interaction between WT RUNX1 and CBFβ. 293T cells were transfected with flag-CBFβ and myc-tagged WT RUNX1 or with RUNX1 mutants. After 48 hours, the proteins were prepared for anti-flag immunoprecipitation, followed by WB with anti-flag and anti-myc Abs. H78Q, R139G, D171G, R174Q, and G381fs-ter570, especially R293X, but not V91fs-ter94, could compete with WT to bind CBFβ. (F) Interaction between WT and mutated RUNX1 proteins. 293T cells were transiently transfected with flag-RUNX1 together with myc-WT RUNX1 or mutants. After 48 hours, whole-cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-flag Ab and analyzed by WB with anti-myc (top panel) and anti-flag (bottom panel) Abs. Flag-RUNX1 efficiently interacts with myc-WT RUNX1, H78Q, R139G, D171G, and R174Q, but not with V91fs-ter94, R293X, or G381fs-ter570. (G) Gel-filtration analysis. Protein fractions collected from the indicated elution volumes were analyzed by WB using anti-myc Ab. Vertical lines show the positions of the corresponding size standards.

Abilities of RUNX1 mutants to bind DNA and heterodimerize with CBFβ

The RHD of RUNX1 is responsible for both DNA binding and heterodimerization with CBFβ.19 To analyze the DNA-binding ability of RUNX1 mutants, an oligonucleotide probe containing the consensus RUNX1-binding sequence and nuclear extracts from 293T cells transfected with WT RUNX1 or mutants were used in gel-shift analysis.20 A DNA/protein complex was detectable using nuclear extracts from the transfectants expressing WT RUNX1, mutated RUNX1 R293X, or G381fs-ter570 (Figure 3B). However, the DNA/protein complex was undetectable for those RUNX1 mutants in the RHD, including H78Q, V91fs-ter94, R139G, D171G, and R174Q, indicating that these mutants had lost their DNA-binding potential.

Because RUNX1 mutants either lost transregulatory activity or could even suppress that of WT RUNX1, we examined their binding ability to target promoter using the ChIP-qPCR assay in the 32D cell line. Five consensus target genes of RUNX1, IL3, MPO, M-CSFR, GM-CSF, and TCRβ, were analyzed.27-32 As shown in Figure 3C, WT RUNX1 could highly enrich the promoter region of these 5 candidate genes compared with mock. In contrast, RUNX1 H78Q, V91fs-ter94, R139G, D171G, and R174Q lost their ability to bind these target gene-promoter regions.

We performed CoIP assays to determine whether the RUNX1 mutants were still capable of interacting with CBFβ. We found that the truncated RUNX1 mutant V91fs-ter94 lost heterodimerization ability with CBFβ, whereas WT and the other mutants of RUNX1, including H78Q, R139G, D171G, R174Q, R293X, and G381fs-ter570, were coimmunoprecipitated with CBFβ (Figure 3D), suggesting that they could heterodimerize with CBFβ and therefore even compete with WT RUNX1 in heterodimer formation. Indeed, cotransfection of all RUNX1 mutants except V91fs-ter94 was able to reduce WT RUNX1/CBFβ heterodimerization (Figure 3E), with R293X showing the strongest effect.

Interference of RUNX1 oligomer formation by RUNX1 mutants

It has been reported previously that RUNX1 could homodimerize and that the dimerization altered by mutations could impair the ability of RUNX1 to regulate differentiation.33 We analyzed the interaction between WT and mutated RUNX1 proteins with a CoIP experiment and found that WT RUNX1 could efficiently interact with either WT RUNX1 or the H78Q, R139G, D171G, and R174Q mutants, but not with V91fs-ter94, R293X, or G381fs-ter570 (Figure 3F). It has been well established that TFs do not work as monomers and need to form a complex with various proteins for full activity and specificity.34-37 Given that oligomerization might be the mechanism responsible for oncogenic activation of PML-RARα and RUNX1-ETO fusions,38,39 we investigated whether RUNX1 mutants could affect the capacity to form high-molecular-weight complexes of WT RUNX1. As shown in Figure 3G, 3 mutants (R139G, R174Q, and R293X) exerted no obvious disturbance on the high-molecular-weight complex formation of the WT RUNX1 protein, whereas under the effect of the V91fs-ter94, D171G, and G381fs-ter570 mutants, the peaks of complexes shifted to lower-molecular-weight fractions. Therefore, the latter 3 mutants might interfere with the oligomerization ability of WT RUNX1.

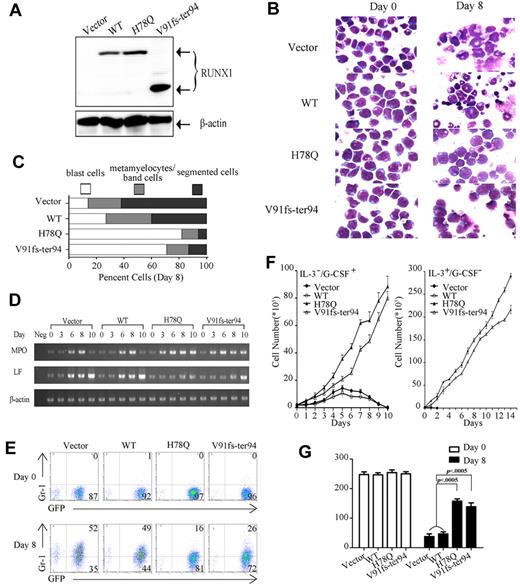

Blockage of granulocytic differentiation of 32D cells by RUNX1 mutants

Because the differentiation of myeloid lineage is impaired in AML-type CML-BC patients, we chose H78Q and V91fs-ter94 to examine at the cellular level the functional consequences of these 2 RUNX1 mutants on granulocytic differentiation programs. Control vector and constructs expressing WT RUNX1 or mutant proteins were stably transfected into 32D cells using retroviral techniques. Four independent cell lines were generated: control vector, WT RUNX1, H78Q, and V91fs-ter94. WB analysis showed that the exogenous proteins were expressed correctly (Figure 4A). The 32D cells could be induced to differentiate into granulocytes by G-CSF, thus providing a model system with which to study the effects of RUNX1 mutations on myeloid lineage.21 G-CSF–mediated differentiation of 32D cells transduced with the empty vector, WT RUNX1, or mutated RUNX1 expression vector was reflected by morphological appearance, the expression of surface marker Gr-1 (granulocyte), and expression of specific genes such as MPO (primary granule) and LF (secondary granule).

Myeloid progenitor–expressing RUNX1 mutants fail to differentiate into granulocytes. (A) Expression of exogenous RUNX1 proteins was detected by WB using RUNX1 polyclonal Ab in 32D cells. (B) Differentiation induction by G-CSF in all 4 indicated stable cell lines. Wright staining of 32D cell lines at day 0 or day 8 of G-CSF treatment. (C) The percentage of 32D cells in 3 different stages of myeloid differentiation is indicated (day 8). (D) The expression profile of MPO and LF mRNA was examined by semi-quantitative RT-PCR in the 4 indicated 32D cell lines with G-CSF treatment for 0, 3, 6, 8, and 10 days. (E) Expression pattern of Gr-1 reveals maturational arrest of 32D cells with RUNX1 mutants. The expression profiles of Gr-1 of 32D cell lines at day 0 or day 8 of G-CSF treatment are shown. (F) Growth properties of 32D stable cell lines. Left, all 4 cell lines were grown in the indicated conditions, and cells were counted each day. The 32D cell lines expressing the mutated RUNX1 protein continue to proliferate when cultured in the presence of G-CSF, whereas the cell lines transfected with vector and WT RUNX1 construct stopped proliferation 5 days after G-CSF treatment. Error bars represent SD. Right, growth curve of the 14 days after withdrawal of G-CSF. Cells expressing either of the 2 mutants kept growing after replacing G-CSF with IL-3, whereas growth of cells with control vector or WT decreased rapidly. Error bars represent SD. (G) Quantification of the colonies for 32D stable cell lines in methylcellulose. 32D cell lines at day 0 or day 8 of G-CSF treatment were plated in methylcellulose medium containing IL-3. Colonies were counted after incubation at 37°C for 14 days.

Myeloid progenitor–expressing RUNX1 mutants fail to differentiate into granulocytes. (A) Expression of exogenous RUNX1 proteins was detected by WB using RUNX1 polyclonal Ab in 32D cells. (B) Differentiation induction by G-CSF in all 4 indicated stable cell lines. Wright staining of 32D cell lines at day 0 or day 8 of G-CSF treatment. (C) The percentage of 32D cells in 3 different stages of myeloid differentiation is indicated (day 8). (D) The expression profile of MPO and LF mRNA was examined by semi-quantitative RT-PCR in the 4 indicated 32D cell lines with G-CSF treatment for 0, 3, 6, 8, and 10 days. (E) Expression pattern of Gr-1 reveals maturational arrest of 32D cells with RUNX1 mutants. The expression profiles of Gr-1 of 32D cell lines at day 0 or day 8 of G-CSF treatment are shown. (F) Growth properties of 32D stable cell lines. Left, all 4 cell lines were grown in the indicated conditions, and cells were counted each day. The 32D cell lines expressing the mutated RUNX1 protein continue to proliferate when cultured in the presence of G-CSF, whereas the cell lines transfected with vector and WT RUNX1 construct stopped proliferation 5 days after G-CSF treatment. Error bars represent SD. Right, growth curve of the 14 days after withdrawal of G-CSF. Cells expressing either of the 2 mutants kept growing after replacing G-CSF with IL-3, whereas growth of cells with control vector or WT decreased rapidly. Error bars represent SD. (G) Quantification of the colonies for 32D stable cell lines in methylcellulose. 32D cell lines at day 0 or day 8 of G-CSF treatment were plated in methylcellulose medium containing IL-3. Colonies were counted after incubation at 37°C for 14 days.

For control vector and WT RUNX1, the cells underwent gross morphological changes of maturation to granulocytes after the replacement of IL-3 with G-CSF (25 ng/mL) for 8 days, and gradually lost viability for the next 2 days (Figure 4B,F). In contrast, 32D cells with expression of H78Q or V91fs-ter94 were blocked at the promyelocytic stage of differentiation under G-CSF treatment (Figure 4B). These results were quantified by scoring for blast cells as immature myeloid progenitors, metamyelocytes/band cells as early stages of myeloid differentiation, and segmented cells as mature granulocytes. A significantly higher percentage of the blast cells was detected in 32D cells with H78Q (average, 82%) and V91fs-ter94 (average, 71%) compared with those transfected with control vector (average, 14%) or WT RUNX1 (average, 27%; Figure 4C). The expression profiles of MPO and LF mRNAs were different in 32D cells expressing H78Q or V91fs-ter94 compared with those with control vector or WT RUNX1 during the 10 days of culture in the presence of G-CSF. For H78Q and V91fs-ter94, MPO expression increased and reached a peak at day 8, but then stayed at that level at day 10, whereas LF expression did not change significantly (Figure 4D). To further determine the precise stage of differentiation block, Gr-1, a surface Ag marker for the later stages of myeloid differentiation, was used to assess the maturational status of the transduced cells by flow cytometry.21 Gr-1 expression was inhibited significantly in cells with RUNX1 H78Q (13.3% ± 4.6%, average ± SD) or V91fs-ter94 (22.7% ± 4.2%, average ± SD) compared with control vector (43.7% ± 9.7%, average ± SD) and WT (38.7% ± 9.1%, average ± SD) after 8 days of treatment with G-CSF (Figure 4E). These results suggested that the RUNX1 mutants H78Q and V91fs-ter94 could block granulocytic differentiation at an early stage. Of note, although 32D cells with control vector and WT gradually lost growth ability in the presence of G-CSF, those with mutations continuously grew. Cells expressing either of the 2 mutants kept growing after replacing G-CSF with IL-3, whereas the growth of cells with control vector or WT decreased rapidly (Figure 4F).

To explore the transforming abilities of the RUNX1 mutations, we next examined the colony-forming ability of the 32D cell lines in methylcellulose. All 4 cell lines isolated at day 0 exhibited similar colony-forming ability, whereas at day 8 after treatment with G-CSF, cells expressing RUNX1 H78Q or V91fs-ter94 formed significantly more colonies than those with either control vector or WT RUNX1 (Figure 4G). The enhanced transforming potential in the mutant cell lines was in agreement with the increased number of immature cells (Figure 4B-E).

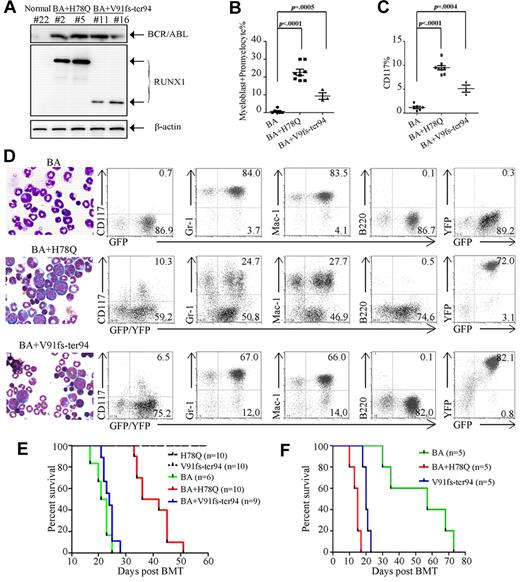

Cooperation between RUNX1 mutants and BCR-ABL to induce an AML-like phenotype

To explore the role of RUNX1 mutations in the progression of CML, we examined the leukemogenic potential of RUNX1 mutants with or without BCR-ABL using a murine BM transduction and transplantation system. MSCV-based retroviral constructs carrying BCR-ABL upstream of an IRES-GFP cassette or RUNX1 mutant upstream of an IRES-YFP cassette were generated and used for cotransduction. The protein expression levels of these constructs were detected in NIH 3T3 cells after cotransduction with retroviral plasmids (supplemental Figure 2). Hematopoietic cells were tracked for in vivo expression of BCR-ABL (GFP+), RUNX1 mutant (YFP+), or both BCR-ABL and RUNX1 mutant (GFP+/YFP+). 5-Fluoruracil–treated BM cells were transduced with RUNX1 mutants H78Q or V91fs-ter94 and BCR-ABL and then transplanted into lethally irradiated syngeneic recipient mice.

BCR-ABL induced a lethal CML-like disease characterized by massive expansion of myeloid cells and infiltration of BM, spleen, and liver, as evidenced by hepatosplenomegaly. The immunophenotype of leukemia cells showed features of granulocytic maturation with increased GFP+/Mac-1+/Gr-1+ cells (Figure 5D, Table 2, and supplemental Table 2) in mice at 17-25 days after BM transplantation (Figure 5E). However, RUNX1 H78Q or V91fs-ter94 alone did not cause obvious hematopoietic disease in mice during an observation period of 120 days.

Functional implications in leukemogenesis of mutated RUNX1 proteins in vivo. (A) WB analysis of BCR-ABL and RUNX1 mutant expression in BM cells of mouse transplanted with stem cells coinfected by BCR-ABL and RUNX1 mutant retroviruses. (B) Quantification of the myeloblast/promyelocyte cells in BM. (C) Quantification of CD117+ cells in the BM. (D) Morphological analysis (left) and immunophenotype analysis (right) of hematopoietic cells from representative diseased mice. BM cytocentrifugation is shown by Wright staining. (E) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of mice transplanted with BM cells transduced with the indicated retroviral constructs. (F) Survival curves of secondary recipient mice transplanted with leukemic cells from BCR-ABL, BCR-ABL plus H78Q, or BCR-ABL plus V91fs-ter94–transduced mice.

Functional implications in leukemogenesis of mutated RUNX1 proteins in vivo. (A) WB analysis of BCR-ABL and RUNX1 mutant expression in BM cells of mouse transplanted with stem cells coinfected by BCR-ABL and RUNX1 mutant retroviruses. (B) Quantification of the myeloblast/promyelocyte cells in BM. (C) Quantification of CD117+ cells in the BM. (D) Morphological analysis (left) and immunophenotype analysis (right) of hematopoietic cells from representative diseased mice. BM cytocentrifugation is shown by Wright staining. (E) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of mice transplanted with BM cells transduced with the indicated retroviral constructs. (F) Survival curves of secondary recipient mice transplanted with leukemic cells from BCR-ABL, BCR-ABL plus H78Q, or BCR-ABL plus V91fs-ter94–transduced mice.

Quantitation of BM cells at different stages of maturation

| BM cells . | BCR-ABL, % (n = 6/6, average ± SD) . | BCR-ABL + H78Q, % (n = 8/10, average ± SD) . | BCR-ABL + V91fs-ter94, % (n = 3/9, average ± SD) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myeloblast/promyelocyte | 0.7 ± 1.2 | 22.6 ± 4.9§ | 9.3 ± 3.2* |

| Late myelocyte/metamyelocyte | 16.7 ± 3.2 | 12.5 ± 8.6‡ | 15.3 ± 17.2 |

| Band neutrophil | 78.5 ± 6.2 | 56.1 ± 14.8§ | 66.3 ± 17.6† |

| Others | 4.2 ± 3.3 | 8.8 ± 6.6 | 9.0 ± 2.6 |

| BM cells . | BCR-ABL, % (n = 6/6, average ± SD) . | BCR-ABL + H78Q, % (n = 8/10, average ± SD) . | BCR-ABL + V91fs-ter94, % (n = 3/9, average ± SD) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myeloblast/promyelocyte | 0.7 ± 1.2 | 22.6 ± 4.9§ | 9.3 ± 3.2* |

| Late myelocyte/metamyelocyte | 16.7 ± 3.2 | 12.5 ± 8.6‡ | 15.3 ± 17.2 |

| Band neutrophil | 78.5 ± 6.2 | 56.1 ± 14.8§ | 66.3 ± 17.6† |

| Others | 4.2 ± 3.3 | 8.8 ± 6.6 | 9.0 ± 2.6 |

Percentages with statistical significance as compared to the BCR-ABL along group.

P < .05

P < .005

P < .0001.

Interestingly, coexpression of BCR-ABL and RUNX1 H78Q caused a CML-BC–like disease, whereas coexpression of RUNX1 V91fs-ter94 and BCR-ABL led to a CML-AP–like phenotype, with a median latency of 39 days and 24 days after transplantation, respectively (Figure 5E and Table 2). Expression of BCR-ABL and RUNX1 mutants was detected in leukemic mice by WB analysis (Figure 5A). Eight of 10 (80%) mice transduced with BCR-ABL plus RUNX1 H78Q and 3 of 9 (33.3%) mice transduced with BCR-ABL plus RUNX1 V91fs-ter94 developed a fatal CML-BC–like or CML-AP–like disease (Table 2), respectively. High numbers (average, 22.6%) of immature cells (myeloblasts + promyelocytes) were present in the BM of leukemic mice with BCR-ABL and RUNX1 H78Q (Figure 5B and Table 2). In contrast to the predominance of mature granulocytic cells in BCR-ABL mice, the fraction of immature cells was also increased in BCR-ABL plus RUNX1 V91fs-ter94 mice, albeit to a lesser extent (average, 9.3%). Flow cytometric analysis of cells from the BM of mice with CML-BC–like or CML-AP–like disease showed that the GFP/YFP–coexpressing cells contained more immature blasts (CD117+, Mac-1−, Gr-1−, and B220−) compared with BCR-ABL mice (Figure 5C-D and supplemental Table 2). These results strongly suggest that RUNX1 H78Q and V91fs-ter94 may impair granulocytic differentiation of BCR-ABL–harboring hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells.

The longer disease latency of the BCR-ABL plus RUNX1 H78Q mice compared with the BCR-ABL alone group might have been because of the fact that more immature leukemic cells tend to be retained in the hematopoietic tissues instead of being released to the circulation and causing thrombosis in capillaries of organs such as the lung. In contrast, BCR-ABL mice develop a much severe hyperleukocytosis (supplemental Table 3), leading to massive infiltration of mature granulocytes in the lungs and subsequent pulmonary hemorrhages, which may be the most likely cause of the rapid death of these mice. A similar phenomenon was observed in previous study's finding that mice expressing both BCR-ABL and RUNX1/MDS1/EVI1 exhibited longer disease latency compared with BCR-ABL mice.7

To determine the self-renewal properties and leukemia-initiating potential of the leukemic cells derived from BCR-ABL plus RUNX1-H78Q or RUNX1-V91fs-ter94, we used sublethally irradiated mice as recipients for secondary transplantation experiments. Indeed, mice with BCR-ABL alone exhibited not only less severe hyperleukocytosis than those in the first transplantation (P < .05), but also much longer survival times—although they all ultimately died of CML-like disease (Figure 5F, supplemental Figure 3, and supplemental Table 3). Conversely, mice bearing both BCR-ABL and RUNX1 mutants displayed hematopoietic disease with phenotypes similar to the primary leukemia but with much more aggressive disease, as evidenced by much shorter survival times.

Discussion

CML provides us with a unique model for studying multistep leukemogenesis, in that it allows a dissection of accumulating and interactive molecular abnormalities involving driver genes and pathways at distinct stages of the disease. In the model used in the present study, the constitutively active tyrosine kinase BCR-ABL generated by the Ph chromosome represents the basic driver of the leukemogenesis at CP, but progression to BC required additional genetic or molecular mutations. The mechanisms responsible for transition of CP into BC are still poorly understood, although some evidence suggests that the phenotype of CML-BC cells characterized by enhanced proliferation, survival advantage, and differentiation arrest depends on cooperation of BCR-ABL with genes dysregulated or with aberrant structure/function during disease progression.

Abnormalities affecting TFs or epigenetic regulators and genes involved in signal transduction represent the most frequently detected genetic events in human acute leukemia. Evidence from animal studies also suggests that genetic alterations of essential signaling molecules such as tyrosine kinases usually lead to a CML-like phenotype and disruption of TFs mainly causes MDS, whereas both events may be required to induce a full-blown acute leukemia. Previous studies have shown that the AML-related fusion TFs NUP98/HOXA9 and RUNX1/MDS1/EVI1 could cooperate with BCR-ABL to induce CML-BC in mouse models.8,40 To test the hypothesis that the involvement of TFs should be critical in CML-BC, we screened several such candidates. Abnormalities of several TF genes such as GATA-2 and RUNX1 have been identified as being related to CML progression for hematopoiesis.17 CML-AP/BC patients with GATA-2 mutations tend to exhibit an acute myelomonocytic leukemia phenotype, whereas patients with RUNX1 mutations have features of acute myeloblastic leukemia in CML-AP/BC. The fact that the RUNX1 mutation was detected in a sizable proportion of CML-AP/BC cases (12.9%), but not among patients during CML-CP (a situation reminiscent of GATA-2 mutations17 ), indicates strongly that these mutations are specifically acquired or selected from a very small subset of the leukemia cell population at CP during CML acute transformation.

Ten types of RUNX1 mutations were identified in our CML-AP/BC patients, and most were located at RHD (7 of 10). It is well known that RHD is the key domain of RUNX1 for transregulatory activity and mediates both DNA binding and heterodimerization with CBFβ.19 We compared the functional consequences of different RUNX1 mutations located at 3 main structural domains, including H78Q, R139G, D171G, R174Q, and V91fs-ter94 in RHD; R293X in TAD; and G381fs-ter570 in TRD. In general, missense, nonsense, and frameshift RUNX1 mutants displayed reduced transactivation activity and/or a dominant-negative function on the WT RUNX1 (Table 3). Consistent with the position of the mutations in the RHD including H78Q, R139G, D171G, and R174Q, DNA binding of these mutant proteins was absent or significantly decreased. These mutants were also capable of inhibiting the transactivation of a reporter gene by WT RUNX1, but retained the ability to heterodimerize with CBFβ. However, the truncated RUNX1 mutant V91fs-ter94, located at the RHD, lost its heterodimerization ability with CBFβ, possibly because of the absence of almost the entire RHD. R293X, another truncated RUNX1 mutant with an intact RHD but deletion of both TAD and TRD, retained its DNA-binding ability and inhibited transactivation, but also led to a more efficient heterodimerization, probably because of the deletion of TRD. RUNX1-related fusion proteins such RUNX1-ETO have been shown to form complexes with CBFβ and other nuclear proteins more efficiently than WT RUNX1.41 Consistent with a previous study,42 our present data suggest that deletion of a negative-regulatory-domain TRD for heterodimerization in the C-terminal region of RUNX1 results in more efficient heterodimer formation.

Biological functions of RUNX1 mutants assayed in this study

| RUNX1 gene . | Subcellular localization . | DNA-binding ability . | CBFβ-binding ability . | Transactivation activity . | Abilities of homodimerization . | Interference of RUNX1 oligomer formation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | N | → | → | → | + | − |

| H78Q | N | ↓ | → | ↓ | + | − |

| V91fs-ter94 | N and C | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | − | + |

| R139G | N and C | ↓ | → | ↓ | + | − |

| D171G | N | ↓ | → | ↓ | + | + |

| R174Q | N | ↓ | → | ↓ | + | − |

| R293X | N | → | ↑ | ↓ | − | − |

| G381fs-ter570 | N | → | → | → | − | + |

| RUNX1 gene . | Subcellular localization . | DNA-binding ability . | CBFβ-binding ability . | Transactivation activity . | Abilities of homodimerization . | Interference of RUNX1 oligomer formation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | N | → | → | → | + | − |

| H78Q | N | ↓ | → | ↓ | + | − |

| V91fs-ter94 | N and C | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | − | + |

| R139G | N and C | ↓ | → | ↓ | + | − |

| D171G | N | ↓ | → | ↓ | + | + |

| R174Q | N | ↓ | → | ↓ | + | − |

| R293X | N | → | ↑ | ↓ | − | − |

| G381fs-ter570 | N | → | → | → | − | + |

N indicates nuclear localization; C, cytoplasmic localization; →, not changed; ↓, decreased; ↑, increased; +, interfered; and −, not interfered.

RUNX1 homodimerizes through a mechanism involving a C terminus to C terminus interaction (aa 372-411).33 Our data showed that R293X and G381fs-ter570, with truncated TRD and elongated peptide, exhibited no ability for homodimerization. However, the G381fs-ter570 mutant behaved abnormally while forming a complex with WT RUNX1, probably because of the partial deletion of TRD or the effect of the abnormally elongated peptide. It is interesting that V91fs-ter94, though losing its ability to interact with CBFβ or DNA, could still exert an inhibitory effect on the transactivation activity of WT RUNX1. One of the reasons for this could be that RUNX1 V91fs-ter94 affects the formation of RUNX1 oligomers. Indeed, the disruption of high-molecular-weight complexes by this truncation mutant was observed, which might disturb the transcription regulation and may explain the inhibitory effect seen in the luciferase reporter assay. Seven truncated RUNX1 mutations with complete or partial deletion of the RHD in 470 adult patients with de novo AML were identified previously by Tang et al,13 so the truncated RUNX1 mutations are recurrent events. However, whether the truncated proteins are indeed expressed in patient cells needs further study, because stop codon mutations at the genomic level occurring in upstream exons often result in unstable mRNA prone to degradation (although the V91fs-ter94 protein was detectable in both transduced cell lines and mouse models in the present study).

Previous studies have shown that RUNX1 mutations exhibit a dominant-negative function in AML,43 suggesting that this effect is also crucial for the pathogenesis of other RUNX1-related leukemias. According to our biochemistry and functional analysis data, we hypothesize that RUNX1 mutations might exhibit a dominant-negative function through 2 different molecular mechanisms. First, mutated RUNX1 might competitively inhibit the binding either between WT RUNX1 and DNA or WT RUNX1 and CBFβ in heterodimerization or between WT RUNX1 proteins for homodimerization. Second, mutated RUNX1 might affect the capacity of WT RUNX1 to form high-molecular-weight complexes.

It has been reported by others that the RUNX1 D171N mutation may have leukemogenic potential in myeloproliferative neoplasms,44 and was also shown to induce MDS or MDS/AML in a mouse BM transplantation model.45 Mouse experiments from Enver et al showed that expression of the full-length isoform RUNX1b abrogated engraftment potential of murine long-term reconstituting stem cells in a mouse BM transplantation model.46 Interestingly, all of our CML-AP/BC patients with mutated RUNX1 displayed differentiation arrest at the myeloblast stage. Consistent with the myeloblastic features of CML-AP/BC patients with RUNX1 mutations, H78Q and V91fs-ter94 disturbed the G-CSF–induced myeloid differentiation of 32D cells. In vivo studies showed that RUNX1 H78Q or V91fs-ter94 cooperates with BCR-ABL in the induction of CML-BC/AP–like disease in mice, suggesting that RUNX1 mutations play a critical role in the pathogenesis of acute transformation of CML. Our data also show that different RUNX1 mutations have distinct transforming potentials, because 80% of mice with RUNX1 H78Q and BCR-ABL developed a CML-BC–like disease, whereas 33.3% of mice with RUNX1 V91fs-ter94 and BCR-ABL developed a CML-AP–like disease. These results seem to agree with our biochemistry data showing a higher dominant-negative effect of H78Q than V91fs-ter94 on the transregulatory activities of WT RUNX1.

In conclusion, we screened a relatively large cohort of Chinese CML-BC or CML-AP patients for genetic abnormalities and conducted a spectrum of biochemical experiments to characterize the function of the various RUNX1 mutants. In this study, we have developed a useful mouse model for further exploration of the mechanisms by which RUNX1 mutations contribute to CML acute transformation, and have shown that RUNX1 is a key molecule in acute transition in CML. The present mouse model will shed light on our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying acute transformation of CML, and may lead to a better therapeutic outcome for patients with this difficult leukemia.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National High Tech Program for Biotechnology (863:2012AA02A505), the Chinese National Key Basic Research Project (973: 2010CB529200), Mega-projects of Science Research for the 10th Five-Year Plan (2008ZX09312-026), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30830119 and 30821063), and by the Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation Co–Project Investigator.

Authorship

Contribution: Z.C. and S.-J.C. designed the research; L.-J.Z., Y.-Y.W., G.L., L.-Y.M., X.-Q.W., W.-N.Z., and B.W. performed the research; S.-M.X., Z.C., and S.-J.C. analyzed the data; and L.-J.Z., Y.-Y.W., Z.C., and S.-J.C. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Sai-Juan Chen and Zhu Chen, State Key Laboratory of Medical Genomics, Shanghai Institute of Hematology, Rui Jin Hospital Affilated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, 197 Rui Jin Road II, Shanghai, 200025, China; e-mail: sjchen@stn.sh.cn or zchen@stn.sh.cn.

References

Author notes

L.-J.Z. and Y.-Y.W. contributed equally to this work.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal