In this issue of Blood, Mahnke and colleagues identify polyfunctional CD4+ T-cell responses directed against specific opportunistic pathogens in HIV-infected patients who develop immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) after initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART).1 This work provides a mechanistic advance to our understanding of IRIS pathogenesis.

HIV-associated IRIS is an adverse clinical manifestation that occurs in HIV-infected individuals treated successfully with ART and consists of a paradoxical deterioration of clinical status despite improved CD4+ T-cell counts and immunologic conditions.2,3 Prior reports have characterized the key clinical features of IRIS, which typically occurs in the first few months of ART and appears to be characterized by a markedly proinflammatory response to a number of pathogens that commonly cause AIDS-associated opportunistic infections (eg, mycobacteria, CMV, cryptococci).3 This inflammatory response is known as either “unmasking” or “paradoxical,” depending on whether the provoking opportunistic infection is previously undiagnosed or whether a known infection worsens subsequent to adequate treatment, respectively. Patients with either form of IRIS can develop fever and a range of organ system pathologies, including pneumonitis, meningitis, uveitis, and lymphadenitis.2,3

Despite detailed clinical characterization, few groups have attempted to delineate a pathophysiologic link between the immune dysregulation induced by HIV infection and the development of an inflammatory response following the immunologic reconstitution observed after initiation of ART. In this study, Mahnke et al show that IRIS related to mycobacterial and fungal organisms is characterized by an expansion of highly differentiated, effector memory CD4+ T cells that secrete IFNγ and TNFα (and in some instances IL-2) when stimulated by antigen(s) from the underlying opportunistic pathogen.1 Importantly, these expansions are not found in ART-treated HIV-infected individuals who do not develop IRIS. Interestingly, they found no difference in the level or phenotype of HIV-specific CD4+ T-cell responses in patients who experience IRIS when measured before and after ART initiation as well as before-and after IRIS onset. In addition, they found that these HIV-specific responses were similar between patients who did or did not develop IRIS. Unfortunately, Mahnke et al could not find any distinguishing feature of either CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell responses at the time of ART initiation that appeared to predict the future development of IRIS, thus precluding the identification of a subset of high-risk HIV-infected patients who could benefit from targeted preventative strategies (as these emerge). Despite this limitation, these data are of interest because they further our understanding of IRIS pathogenesis by defining a common immunologic mechanism linking phenotypically and functionally similar CD4+ T-cell responses to multiple pathogens with the clinical development of this syndrome.

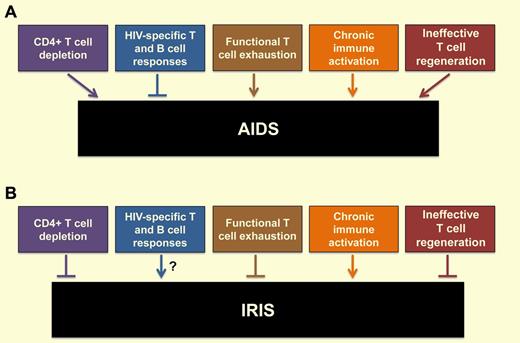

The interaction between HIV and the host immune system is remarkably complex (see figure) and includes the following features: (1) depletion of CD4+ T cells by both direct virus infection and bystander apoptosis, which is more pronounced at the level of memory cells located in the mucosal immune system, thus leading to a significant defect in T-helper function4 ; (2) generation of vigorous HIV-specific T- and B-cell responses that usually fail to fully suppress virus replication5 ; (3) development of functional T-cell exhaustion that is associated with increased expression of specific T-cell inhibitory molecules6 ; (4) establishment of a state of chronic, generalized immune activation that predicts the progression to AIDS4 ; and (5) ineffective T-cell regeneration with impaired function of the thymus and bone marrow and disruption of lymph node architecture.4 The pathophysiologic role of CD4+ T-cell responses is particularly ambiguous, as these responses may protect against both HIV and opportunistic pathogens and at the same time provide additional targets for virus infection.4 As the inhibition of virus replication induced by ART leads to a significant reversion of the HIV-associated abnormalities described above and a major reduction in morbidity and mortality, the development of IRIS represents the paradoxical clinical complication of an overall better functioning immune system (see figure). Conceivably, the immune system reconstitution induced by ART, with the accompanying rapid reactivation and expansion of pre-existing but previously depleted and/or exhausted CD4+ T-cell clones specific for subclinical or formerly controlled infections may result in poorly regulated immune responses that, for reasons that we do not fully understand, take a marked proinflammatory, tissue-damaging flavor. In this context, the observation of vigorous, polyfunctional, and predominantly effector-memory CD4+ T cells specific for certain opportunistic pathogens in IRIS patients may define a subset of immune cells responsible for this phenotype.1

Consequences of HIV infection on the host immune system and how these features impact the development of (A) AIDS and (B) IRIS.

Consequences of HIV infection on the host immune system and how these features impact the development of (A) AIDS and (B) IRIS.

However, many questions regarding the immunopathogenesis of IRIS remain unanswered. First and foremost, what is the precise mechanistic role of pathogen-specific CD4+ T cells, and what other innate and adaptive immune cell types contribute to the IRIS-associated proinflammatory state? Second, what distinguishes the chronic immune activation of the natural history of HIV infection, which is usually reduced by ART, from the immune activation that is typical of IRIS? Third, what sort of pre-existing immune abnormalities confer an increased risk of developing IRIS after initiation of ART? Fourth, to what extent is this expansion of effector memory CD4+ T cells related to the HIV-associated depletion of central memory CD4+ T cells that is known to be a key factor in AIDS pathogenesis?7 Fifth, what are the similarities and differences in the pathogenesis of the various clinical manifestations of IRIS that occur in association with different pathogens? Ultimately, it is our hope that further insight into the pathogenesis of IRIS will allow for the development of novel immune-based interventions that can prevent and treat this potentially serious clinical complication of HIV-infected patients starting ART.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests. ■

REFERENCES

National Institutes of Health

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal