Abstract

The transcription factor runt-related transcription factor 1 (Runx1) is essential for the establishment of definitive hematopoiesis during embryonic development. In adult blood homeostasis, Runx1 plays a pivotal role in the maturation of lymphocytes and megakaryocytes. Furthermore, Runx1 is required for the regulation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. However, how Runx1 orchestrates self-renewal and lineage choices in combination with other factors is not well understood. In the present study, we describe a genome-scale RNA interference screen to detect genes that cooperate with Runx1 in regulating hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. We identify the polycomb group protein Pcgf1 as an epigenetic regulator involved in hematopoietic cell differentiation and show that simultaneous depletion of Runx1 and Pcgf1 allows sustained self-renewal while blocking differentiation of lineage marker–negative cells in vitro. We found an up-regulation of HoxA cluster genes on Pcgf1 knock-down that possibly accounts for the increase in self-renewal. Moreover, our data suggest that cells lacking both Runx1 and Pcgf1 are blocked at an early progenitor stage, indicating that a concerted action of the transcription factor Runx1, together with the epigenetic repressor Pcgf1, is necessary for terminal differentiation. The results of the present study uncover a link between transcriptional and epigenetic regulation that is required for hematopoietic differentiation.

Introduction

The runt-related transcription factor 1 (Runx1), also known as AML1, is a master regulator of fetal and adult hematopoiesis. During development, Runx1 is indispensable for the establishment of definitive hematopoiesis.1 In the adult, Runx1 deficiency severely disturbs various steps of blood cell synthesis.2-4 Conditional Runx1-knockout mice display an increased pool of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), myeloid progenitor cells (MPCs), and granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMPs) in the BM, demonstrating a role of Runx1 in the maturation of these cells.2-4 In addition to its effect on immature hematopoietic cells, Runx1 is required for efficient differentiation of both the myeloid and lymphoid lineage during later steps of hematopoiesis. Conditional Runx1-knockout mice show a megakaryocyte maturation arrest leading to micromegakaryocytes in the BM and thrombocytopenia in the blood.2,4 Lymphopoiesis is also severely affected at several stages in the absence of Runx1. Maturation of immature CD4 and CD8 double-negative T cells fails in Runx1-knockout mice.2,4,5 Furthermore, B-cell differentiation is blocked at an early step, because almost no pre-B cell precursors can be detected in the absence of Runx1.2,4,5

The importance of Runx1 in hematopoiesis is further underlined by the fact that the Runx1 gene is one of the most frequently deregulated genes in leukemia.6 Prevalent Runx1 mutations are chromosomal translocations that result in a dominant-negative effect over the wild-type protein.7 In approximately 25% of the minimally differentiated acute myeloid leukemia (AML) subtype M0 cases, biallelic mutations leading to loss of function of Runx1 can be detected and are connected to poor prognosis of disease outcome.6 Monoallelic mutations in Runx1 cause familial platelet disorder with a predisposition to AML.7

In agreement with its significance during hematopoiesis, Runx1 is widely expressed within the hematopoietic system and can both positively and negatively regulate a plethora of genes.8 Runx1 dimerizes with its cofactor CBFβ via the N-terminal runt homology domain to form the core binding factor complex.9 The runt homology domain also recognizes a consensus binding site in promoters of Runx1 target genes.10 The C-terminal transactivation domain allows further target specificity by interacting with multifunctional coactivators such as p300 and CBP.11 Runx1 also cooperates with other transcription factors during hematopoietic cell-fate decisions by co-occupying promoters in concert with key players such as GATA-2.12 Because Runx1 regulates gene expression at many different stages during hematopoiesis, the transcriptional pattern modified by Runx1 strongly depends on the cellular context, as defined by the expression levels of other transcriptional regulators together with the epigenetic signature of the chromatin.13,14 A prominent example of cell context dependency is the regulation of the thrombopoietin receptor gene cMpl by Runx1. In hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), Runx1 interacts with mSIN3A to suppress the expression of cMpl, whereas in megakaryocytes, Runx1 interaction with p300 activates the same gene.15

For a better understanding of Runx1 function, it is therefore crucial to investigate factors that determine cellular fate synergistically together with Runx1. However, the identification of such cooperativity is often not straightforward, especially when it is not mediated through physical interaction, but rather through genetic interplay. In yeast, systematic genetic interactions have been mapped by crossing a collection of deletion strains.16 However, in higher eukaryotes, these types of experiments have not been possible thus far. Only with the development of RNA interference have systematic large-scale genetic interaction screens become feasible in human cancer cell lines.17,18 However, despite the artificial cellular background that cultured cancer cells provide, such screens have been rarely carried out in primary cells. In the present study, we report a pooled genome-wide, shRNA-based Runx1 genetic interaction screen in primary mouse hematopoietic cells. Our screen identifies cooperation between Runx1 and the polycomb group protein Pcgf1 in regulating the self-renewal and differentiation of lineage marker–negative (Lin−) cells.

Pcgf1 belongs to the group of mammalian Drosophila posterior sex comb (psc) homologs.19 As part of different polycomb group repressive complex 1 (PRC1) variants, the psc homologs participate in gene repression by enhancing ubiquitination of the histone H2A.20,21 Pcgf1 belongs to the PRC1-like BCOR complex, along with Ring1A, RNF2, RYBP, the BCL6-interacting corepressor BCOR, and components of the SCF ubiquitin ligase, Fbxl10 and Skp1.22,23 Like PRC1, the BCOR complex mediates the mono-ubiquitination of H2A, and is recruited to BCL6 target genes in B cells.22 In contrast to BMI-1, another psc homolog that is well known for its role in regulating self-renewal in HSCs,24 Pcgf1 has thus far not been linked to hematopoiesis.

In the present study, we report a strong gain in self-renewal and block in differentiation of Lin− mouse cells simultaneously depleted of Pcgf1 and Runx1. When analyzing these cells, we found that they resembled immature progenitor cells. Furthermore, Pcgf1 was most strongly expressed in hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs), but significantly less so in differentiated blood cells and in HSCs. Gene-expression analyses suggested that Pcgf1 functions in suppressing self-renewal by down-regulating HoxA cluster genes. Our data indicate that Pcgf1 primes hematopoietic progenitors for maturation epigenetically, whereas Runx1 initiates the transcription of genes required for their differentiation.

Methods

Mouse strains

Runx1fl/fl mice containing the IFN-responsive Mx1-Cre gene or control cells lacking Mx1-Cre have been described previously.4 Excision of floxed exon 5 of the runx1 gene was induced by 6 IP injections of poly(I:C) (LMW; InvivoGen) at a dose of 10 μg/g body weight applied every 2 days. Control mice lacking Mx1-Cre were treated the same way. Recombination was checked by PCR.4 Rag2−/−γc−/−KitWv/Wv mice are receptive for syngeneic and allogeneic mouse HSCs.25 C57BL/6 OlaHsd mice were obtained from Harlan Laboratories.

Pcgf1-enhanced green fluorescent protein (Pcgf1-eGFP) mice were generated as described previously26 by transfecting R1/E mouse embryonic stem cells with the BAC clone RP24-253F2 obtained from the BACPAC Resource Center (http://bacpac.chori.org; for further details, see supplemental Methods, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Mouse lines were maintained in pathogen-free conditions in the animal facility of the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (Dresden, Germany). Experiments were performed in accordance with German animal welfare legislation. Animal experiments were approved by the Landesdirektion Dresden.

shRNA library, shRNA vectors, and generation of murine retrovirus

The pRetroSuperCam mouse shRNA library was a kind gift from René Bernards and Roderick Beijersbergen (Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The library contains approximately 30 000 different shRNA vectors targeting approximately 15 000 mouse genes.27 Viral supernatant was produced in Phoenix-GP cells (provided by G. Nolan, Stanford University, Stanford, CA) as described previously (http://www.stanford.edu/group/nolan/protocols/pro_helper_dep.html). Cells (1 × 107) were transfected with 18 μg of pRS, 5 μg of p522, and 10 μg of pR690 plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Viral supernatant was harvested every 12 hours for 24 hours after transfection. Single shRNAs were cloned into the pRS vector containing a puromycin resistance cassette or in a vector in which this cassette was replaced by eGFP (shPcgf1 #1: 5′-AAAAAGAAATTAACTGTGGCTTTATCTCTTGAATAAAGCCACAGTTAATTTC-3′; shPcgf1 #2: 5′-AAAAAGGACATAGTGTATAAGCTAGTTCTCTTGAAACTAGCTTATACACTATGTCC-3′; shCtrl: 5′-A-AAAACTGCCTGATCAGCTCGTCATCTCTTGAATGACGAGCTGATCAGGCAG-3′; shBcorl1 #1: 5′-CTCCAGAGCAGGATGCTGTCACAAAGAAC-3′; shBcorl1 #2: 5′-CTGATAAGTCTGTATCACTGTGACGATTT-3′; shBcorl1 #3: 5′-GAGGCAATAATACGGACCAACAAGAAGCC-3′).

Isolation and transduction of lineage-depleted hematopoietic cells

Mouse BM was isolated from femurs and tibias. After erythrocyte lysis, cells were lineage depleted using the Lineage Cell Depletion Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were cultivated for 48 hours in StemSpan SFEM (StemCell Technologies) supplemented with 10 ng/mL of murine SCF, 20 ng/mL of murine thrombopoietin, 10 ng/mL of human fibroblast growth factor 1 (PeproTech), 20 ng/mL of murine insulin-like growth factor 2 (R&D Systems), 10 μg/mL of heparin (BiochromAG), and 100 μg/mL of primocin (Invivogen). For transduction, plates were coated with 50 μg/mL of retronectin (TaKaRa). Next, 3 mL of viral supernatant was spin-occulated in the presence of 100 mM HEPES and 0.4 μg/mL polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich) onto a 6-well plate at 2000 rpm for 20 minutes. After repeating this procedure 2 or 3 times, 7.5 × 105 Lin− cells in 1.5 mL SFEM and 1.5 mL viral supernatant with 100 mM HEPES were spinoculated onto the virus-coated plate. Supernatant was removed after 4 hours. Twenty-four hours after transduction, cells were either selected with 5 μg/mL of puromycin for 48 hours or, in the case of engraftment experiments, injected directly into mice.

Methylcellulose colony-forming assay

For the first plating, 8000 cells in 100 μL of IMDM (GIBCO) were mixed with 1 mL of MethoCult GF M3434 (StemCell Technologies) and 100 μg/mL of primocin (Invivogen) and plated into 6-well plates. Cells were kept extra moist at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 7 days. Cells were then regained, counted, and 20 000-60 000 cells were replated into fresh methylcellulose. Only samples that formed colonies were considered to possess self-renewal capacity. Images of colonies were taken using a Canon Powershot G12 camera attached to an Olympus inverted microscope with a 4× objective.

Sequencing of shRNAs

shRNAs from purified genomic DNA were amplified with primers fwd 5′-CCCTTGAACCTCCTCGTTCGACC-3′ and rev 5′-GAGACGTGCTACTTCCATTTGTC-3′, and subcloned into pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen). Sequencing was performed using T3 and T7 primers at the DNA sequencing facility of the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics.

May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining

Cells were spun onto slides in a cytospin centrifuge (Shandon) and stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Samples were analyzed on a Zeiss wide-field microscope with a 63× oil objective (Olympus) using AxioVision Version 4.8 software.

Immunophenotyping by FACS

Cells were stained with the Abs listed in supplemental Methods. Data were acquired on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer or a FACSAria II cell sorter (both BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo Version 7.6.4/9.3 software (TreeStar).

Engraftment experiments

C57BL/6 mice (Ly5.1) were lethally irradiated using 1 dose of 9 Gy for 24 minutes. Lineage-depleted and transduced BM cells (7 × 106; Ly5.2) with 3.5 × 105 spleen cells (Ly5.1) were injected into the tail veins of recipient animals. Alternatively, 1 × 106 unsorted donor cells or 2 × 105 FACS-sorted donor cells were injected into nonirradiated Rag2−/−γc−/−KitWv/Wv mice. Mice were given 1.17 mg/mL of neomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) in the drinking water for 2 weeks after transplantation.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). cDNA was generated with the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (QIAGEN). Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed with QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (QIAGEN). Samples were analyzed on an Mx3000p (Stratagene). Samples were run in triplicate and transcript levels were calculated as 2(−ΔΔ Ct) and normalized to β-actin. Primer sequences are listed in supplemental Table 1.

Microarray

Lin− cells from 4 independent Runx1Δ/Δ mice were transduced with Pcgf1 or control shRNA. After 36 hours of puromycin selection, total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Kit (QIAGEN). Microarrays were carried out as described in supplemental Methods on 4 × 44K Agilent Whole Genome GEX IC Mouse arrays (Agilent Technologies). Data were analyzed with GeneSpring Version 10 software (Agilent) and can be accessed at the Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) as accession number GSE33280.

ChIP

ChIP assays were performed essentially as described previously28 (see supplemental Methods) using ubiquityl-histone H2A Ab (Millipore). ChIP assays with polyclonal goat anti-GFP Ab28 were performed in cells isolated from Pcgf1-eGFP mice. The fold enrichments were quantified by qRT-PCR with the primers listed in supplemental Table 2.

Results

Identification of Pcgf1 as a negative regulator of self-renewal in Lin− cells

To screen for factors that cooperate with Runx1 in regulating the self-renewal of HSPCs, we performed a genome-scale shRNA screen in primary Lin− cells isolated from conditional Runx1-knockout mice (Runx1Δ/Δ).4 For monitoring self-renewal, we used an in vitro replating assay in methylcellulose.29 Under these conditions, wild-type Lin− cells differentiate into granulocyte, macrophage, and erythrocyte colonies within 7-10 days until the pool of stem and progenitor cells is exhausted. Cells with an enhanced self-renewal capacity gain a selective growth advantage over wild-type cells and can be isolated and analyzed after several weeks of serial replating. The strategy of the screen is outlined in Figure 1A.

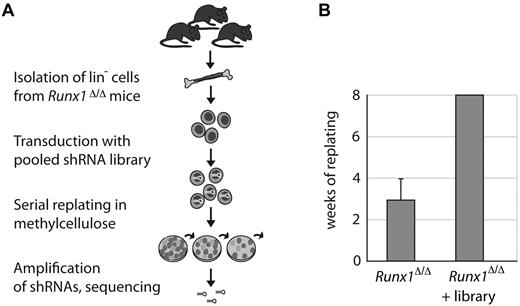

Pooled shRNA-based Runx1 genetic interaction screen in primary mouse hematopoietic cells. (A) Schematic of the shRNA screen. Lineage-depleted hematopoietic cells were isolated from femurs and tibias of 3 conditional Runx1-knockout mice (Runx1Δ/Δ). Cells were retrovirally transduced with a genome-wide shRNA library. Transduced cells were plated into methylcellulose containing stem cell factor, IL-3, IL-6, and erythropoietin. Cells were replated weekly into fresh methylcellulose. After 8 weeks of serial replating, remaining shRNAs were recovered and sequenced. (B) Runx1Δ/Δ Lin− cells transduced with the library formed colonies in methylcellulose for more than 8 weeks. Nontransduced cells were plated in triplicate. Error bars indicate the SDs of plating capacities from 3 independent experiments.

Pooled shRNA-based Runx1 genetic interaction screen in primary mouse hematopoietic cells. (A) Schematic of the shRNA screen. Lineage-depleted hematopoietic cells were isolated from femurs and tibias of 3 conditional Runx1-knockout mice (Runx1Δ/Δ). Cells were retrovirally transduced with a genome-wide shRNA library. Transduced cells were plated into methylcellulose containing stem cell factor, IL-3, IL-6, and erythropoietin. Cells were replated weekly into fresh methylcellulose. After 8 weeks of serial replating, remaining shRNAs were recovered and sequenced. (B) Runx1Δ/Δ Lin− cells transduced with the library formed colonies in methylcellulose for more than 8 weeks. Nontransduced cells were plated in triplicate. Error bars indicate the SDs of plating capacities from 3 independent experiments.

First, we validated the serial replating assay. As expected, Lin− cells from Runx1Δ/Δ mice had a moderately enhanced plating capacity of 4 weeks compared with cells from control mice (Runx1fl/fl), which stopped forming colonies after the second plating (supplemental Figure 1A). Retroviral overexpression of Runx1/ETO, which is known to immortalize HSPCs,30 resulted in a replating capacity of 8 weeks (supplemental Figure 1A), demonstrating the functionality of the assay. For the screen, Runx1Δ/Δ Lin− cells were transduced with the pooled shRNA library,27 cultivated in methylcellulose, and replated weekly. We were able to replate the Runx1Δ/Δ–transduced cells for more than 8 weeks, indicating that the expression of certain shRNAs had increased the replating capacity substantially (Figure 1B). To identify shRNAs that led to the enhanced replating capacity in Runx1Δ/Δ cells, we isolated the DNA from these cells after 8 weeks in culture and determined the shRNA sequences present in the pool. Strikingly, in 41% of the sequenced shRNA clones, we found the same shRNA targeting the polycomb group protein Pcgf1, indicating that cells expressing this shRNA had been enriched during the replating assay.

Simultaneous depletion of Runx1 and Pcgf1 increases the self-renewal capacity of Lin− cells

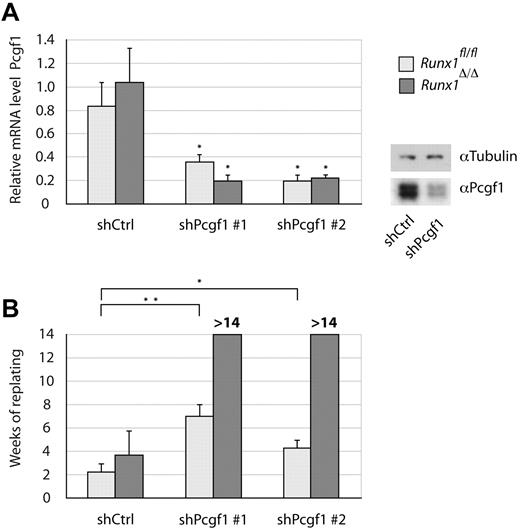

To validate the phenotype of Pcgf1 knockdown in Runx1Δ/Δ cells, Lin− cells were either transduced with the shRNA found in our screen or with a second shRNA targeting Pcgf1 to exclude off-target effects. Efficient knockdown of Pcgf1 by both shRNAs was confirmed 48 hours after transduction by qRT-PCR and Western blot (Figure 2A). When cultivating cells expressing shRNAs directed against Pcgf1 in methylcellulose, Runx1fl/fl Lin− cells could be replated significantly longer than cells transduced with a control shRNA (Figure 2B). However, these cells only formed colonies for 8 weeks at most. Remarkably, the same treatment of Runx1Δ/Δ Lin− cells virtually immortalized the cells. In several independent experiments, these cells could be cultivated for at least 15 weeks in methylcellulose, when most experiments were stopped. However, cultures of independent experiments were kept for up to 60 weeks (supplemental Figure 1B), indicating massively increased replating capacity. In contrast, overexpression of Pcgf1 led to massive cell death (data not shown).

Simultaneous Runx1 and Pcgf1 depletion strongly increases the self-renewal of Lin− BM cells. Lin− cells isolated from Runx1Δ/Δ (dark gray) or Runx1fl/fl (light gray) control mice transduced with 2 different shRNAs targeting Pcgf1 (shPcgf1 #1 and shPcgf1 #2) or a scrambled shRNA (shCtrl) are shown. (A) Pcgf1 knockdown levels as determined by isolating total mRNA and performing qRT-PCR using primers specific for Pcgf1 are shown. RNA levels were normalized to β-actin. Mean values of 3 independent experiments are shown. The significance of knock-down levels was determined by the Student t test. *P < .05. Alternatively, protein lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting using an Ab specific for Pcgf1 or α-tubulin as a loading control. (B) Replating capacity of Lin− BM cells transduced with the indicated shRNAs. Mean values and SDs of 3 independent experiments are shown. Significance was determined by the Student t test. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Simultaneous Runx1 and Pcgf1 depletion strongly increases the self-renewal of Lin− BM cells. Lin− cells isolated from Runx1Δ/Δ (dark gray) or Runx1fl/fl (light gray) control mice transduced with 2 different shRNAs targeting Pcgf1 (shPcgf1 #1 and shPcgf1 #2) or a scrambled shRNA (shCtrl) are shown. (A) Pcgf1 knockdown levels as determined by isolating total mRNA and performing qRT-PCR using primers specific for Pcgf1 are shown. RNA levels were normalized to β-actin. Mean values of 3 independent experiments are shown. The significance of knock-down levels was determined by the Student t test. *P < .05. Alternatively, protein lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting using an Ab specific for Pcgf1 or α-tubulin as a loading control. (B) Replating capacity of Lin− BM cells transduced with the indicated shRNAs. Mean values and SDs of 3 independent experiments are shown. Significance was determined by the Student t test. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Because cell numbers did not decrease significantly within the first weeks of plating, the majority of Lin− cells transduced with a Pcgf1 shRNA appeared to be capable of extended self-renewal (supplemental Figure 1C). Retroviral integration events could be excluded as a possible cause of the enhanced plating capacity, because similar results in multiple experiments and with different shRNAs were obtained, whereas increased replating capacity was never seen in cells transduced with a control shRNA. Moreover, ligase-mediated PCR assays and Southern blot analysis with a gene probe complementary to the puromycin resistance gene did not reveal recurrent integration sites among different experiments (data not shown), supporting a direct implication of Pcgf1 depletion in the enhanced replating phenotype. We therefore conclude that the concomitant depletion of Runx1 and Pcgf1 blocks the differentiation of Lin− cells in methylcellulose, and at the same time enables them to self-renew significantly longer than control cells. Knock-down of Pcgf1 or knockout of Runx1 alone only showed a mild effect, revealing cooperativity between these 2 factors.

Runx1- and Pcgf1-depleted cells reveal an immature phenotype

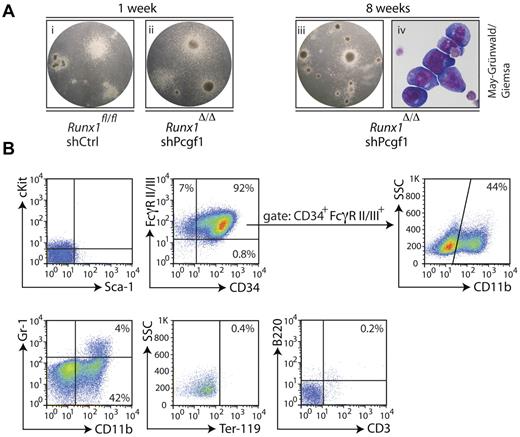

After several weeks of serial replating in methylcellulose, Runx1Δ/Δ Lin− cells transduced with a Pcgf1 shRNA formed immature, small, tight colonies, often with a dark core in the center (Figure 3A). Differentiated myeloid cells that typically surround colonies from wild-type Lin− cells after 1 week in methylcellulose were mostly absent; instead, May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining showed immature, blast-like colonies with a high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio in long-term-cultured cells (Figure 3A).

Runx1Δ/Δ cells with a Pcgf1 knockdown reveal immature characteristics. (A) Lin− cells isolated from the BM of Runx1Δ/Δ or control mice (Runx1fl/fl) transduced with an shRNA targeting Pcgf1 (shPcgf1) or a scrambled shRNA (shCtrl) plated into methylcellulose at indicated time points are shown. Note the formation of similar colonies after 1 week (i-ii), in contrast to the dense colonies that lack mature-looking cells after 8 weeks of replating of the Runx1Δ/Δ cells transduced with the Pcgf1 shRNA (iii). Cytospins of cells from subpanel iii stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa revealed a blast-like appearance (iv). (B) FACS immunophenotyping of Runx1Δ/Δ cells with Pcgf1 knockdown after 9 weeks of serial replating in methylcellulose. Cells were stained with the indicated Abs. The lower left quadrant was set according to the appropriate isotype controls. The percentage of cells measured in the gated populations is indicated.

Runx1Δ/Δ cells with a Pcgf1 knockdown reveal immature characteristics. (A) Lin− cells isolated from the BM of Runx1Δ/Δ or control mice (Runx1fl/fl) transduced with an shRNA targeting Pcgf1 (shPcgf1) or a scrambled shRNA (shCtrl) plated into methylcellulose at indicated time points are shown. Note the formation of similar colonies after 1 week (i-ii), in contrast to the dense colonies that lack mature-looking cells after 8 weeks of replating of the Runx1Δ/Δ cells transduced with the Pcgf1 shRNA (iii). Cytospins of cells from subpanel iii stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa revealed a blast-like appearance (iv). (B) FACS immunophenotyping of Runx1Δ/Δ cells with Pcgf1 knockdown after 9 weeks of serial replating in methylcellulose. Cells were stained with the indicated Abs. The lower left quadrant was set according to the appropriate isotype controls. The percentage of cells measured in the gated populations is indicated.

To further characterize these cells, we analyzed the surface expression of various stem cell, progenitor, and differentiation markers. The stem cell markers cKit and Sca-1 were not detected on the surface of Runx1Δ/Δ Lin− cells transduced with Pcgf1 shRNA (Figure 3B). Therefore, despite their enhanced self-renewal capacity, these cells do not resemble HSCs. In contrast, the majority of cells expressed CD34 (Figure 3B), a marker that is normally found on immature HSPCs. In addition, a large fraction of the cells coexpressed CD34 and FcγRII/III, factors usually present on GMPs together with cKit.31 Almost half of the cells within the CD34 and FcγRII/III double-positive population expressed CD11b (Figure 3B), a marker for mature granulocytes, monocytes, macrophages, a subset of B cells, and natural killer cells that is commonly not expressed together with CD34. Furthermore, the granulocyte marker Gr-1 was present on some CD11b+ cells, suggesting that a subset of cells differentiated toward the granulocyte lineage. Despite the presence of erythropoietin in the methylcellulose, we did not detect the erythroid marker Ter-119, indicating that differentiation into this lineage is blocked in Runx1-Pcgf1 double-negative cells. The lymphoid markers B220 and CD3 were also not expressed (Figure 3B).

In summary, characterization of cells lacking both Runx1 and Pcgf1 revealed an immature phenotype, as seen by their microscopic appearance and the expression of the progenitor cell marker CD34. However, they did not resemble HSCs or any defined progenitor cell type. In addition, the expression of myeloid differentiation markers on immature CD34+ cells indicates that some cells might have activated inappropriate myeloid maturation programs.

Pcgf1 is expressed in HPCs

Pcgf1 is a largely uncharacterized protein and has been mainly connected to neurogenesis.32 A function for Pcgf1 in hematopoiesis has not been described thus far. We therefore explored the expression of Pcgf1 within the hematopoietic system. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis revealed no marked differential expression in different lineage-selected fractions, but Pcgf1 was expressed more than twice as highly in Lin− BM cells compared with Lin+ cells from either Runx1fl/fl or Runx1Δ/Δ mice (Figure 4A). No significant difference in Pcgf1 mRNA level was observed between Runx1-knockout and control cells, indicating that Pcgf1 is not regulated by Runx1 in hematopoietic cells.

Pcgf1 is predominantly expressed in HPCs. (A) BM of Runx1Δ/Δ (dark gray) or control mice (Runx1fl/fl, light gray) isolated and separated into 2 fractions that either were enriched for HSPCs (Lin−) or contained mature blood cells (Lin+) are shown. RNA isolated from these cells was analyzed by qRT-PCR for the expression of Pcgf1. Data were normalized to β-actin levels. Mean values of 3 independent experiments are shown. Significance was determined by the Student 1-tailed t test. **P < .01. (B) Microscopic analysis of lineage-depleted BM cells from Pcgf1-eGFP mice. Cells stained for eGFP, DAPI, and α-tubulin are presented. Samples were analyzed by a Deltavision microscope and pictures were deconvoluted. In the overlay, eGFP is depicted in green, DAPI in blue, and α-tubulin in red. (C-D) Representative FACS profiles of BM cells from Pcgf1-eGFP mice. Cells stained with indicated Abs or corresponding isotype controls are shown. Populations were defined as follows: stem cells (LSK) (Lin−cKit+ Sca-1+), MPCs (Lin−cKit+Sca-1−), common myeloid progenitors (CMP) (Lin−cKit+Sca-1−CD34+FcγRII/III−), GMPs (Lin−cKit+Sca-1−CD34+FcγRII/III+), megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitors (MEP) (Lin−cKit+Sca-1−CD34−FcγRII/III−), and common lymphoid progenitors (CLP) (Lin−IL-7Rα+cKitloSca-1lo). (C) Comparison of LSK populations before (right panel) and after (left panel) gating for eGFP+ cells. (D) Mean fluorescence of different hematopoietic cell populations. Gray histogram indicates control mice; clear histogram, Pcgf1-eGFP mice. (E) Percentage of eGFP+ cells from different cell populations of Pcgf1-eGFP mice. Error bars indicate the SD from the mean percentage values of 9 different animals.

Pcgf1 is predominantly expressed in HPCs. (A) BM of Runx1Δ/Δ (dark gray) or control mice (Runx1fl/fl, light gray) isolated and separated into 2 fractions that either were enriched for HSPCs (Lin−) or contained mature blood cells (Lin+) are shown. RNA isolated from these cells was analyzed by qRT-PCR for the expression of Pcgf1. Data were normalized to β-actin levels. Mean values of 3 independent experiments are shown. Significance was determined by the Student 1-tailed t test. **P < .01. (B) Microscopic analysis of lineage-depleted BM cells from Pcgf1-eGFP mice. Cells stained for eGFP, DAPI, and α-tubulin are presented. Samples were analyzed by a Deltavision microscope and pictures were deconvoluted. In the overlay, eGFP is depicted in green, DAPI in blue, and α-tubulin in red. (C-D) Representative FACS profiles of BM cells from Pcgf1-eGFP mice. Cells stained with indicated Abs or corresponding isotype controls are shown. Populations were defined as follows: stem cells (LSK) (Lin−cKit+ Sca-1+), MPCs (Lin−cKit+Sca-1−), common myeloid progenitors (CMP) (Lin−cKit+Sca-1−CD34+FcγRII/III−), GMPs (Lin−cKit+Sca-1−CD34+FcγRII/III+), megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitors (MEP) (Lin−cKit+Sca-1−CD34−FcγRII/III−), and common lymphoid progenitors (CLP) (Lin−IL-7Rα+cKitloSca-1lo). (C) Comparison of LSK populations before (right panel) and after (left panel) gating for eGFP+ cells. (D) Mean fluorescence of different hematopoietic cell populations. Gray histogram indicates control mice; clear histogram, Pcgf1-eGFP mice. (E) Percentage of eGFP+ cells from different cell populations of Pcgf1-eGFP mice. Error bars indicate the SD from the mean percentage values of 9 different animals.

To further investigate the expression of Pcgf1 in hematopoietic cells, we generated a BAC-transgenic mouse strain expressing a Pcgf1-eGFP fusion gene from the endogenous Pcgf1 promoter.26 Pcgf1-eGFP mice developed normally and revealed no obvious abnormalities in hematopoiesis (data not shown). Hematopoietic cells isolated from the BM of these mice expressed various levels of eGFP representing different protein levels of Pcgf1 (supplemental Figure 2A). This discrepancy with the marginal differences in Pcgf1 mRNA levels might reflect posttranscriptional regulation of Pcgf1.

To validate the functionality of the fusion gene, we performed a proteomic analysis on the embryonic stem cells that were used to generate the mice. Virtually all known protein interactors of Pcgf1 in the BAC-transgenic embryonic stem cells were pulled down by coimmunoprecipitation using Pcgf1-eGFP as a bait, demonstrating that the Pcgf1 fusion is part of the BCOR/BCORL1 complex (supplemental Figure 2B-C and supplemental Table 3). Interestingly, depletion of BCORL1, the most abundant Pcgf1 interactor in the mass spectrometry analysis, also extended the replating capacity of Runx1Δ/Δ Lin− cells (supplemental Figure 3), suggesting that a functional Pcgf1-BCORL1 complex cooperates with Runx1 in regulating differentiation and self-renewal of hematopoietic cells.

We also investigated the localization of Pcgf1-eGFP in Lin− cells (Figure 4B). Prominent nuclear staining was observed, which is consistent with a proposed function of Pcgf1 in epigenetic regulation. We conclude that the eGFP-Pcgf1 fusion protein is functional.

To determine which hematopoietic cell populations express Pcgf1, we compared surface marker expression on eGFP-expressing BM cells from eGFP-Pcgf1 mice with the whole fraction of eGFP+ and eGFP− cells by FACS. Among the Pcgf1-eGFP–expressing cells, almost no HSCs were present, as shown by the absence of lineage markers and high expression of Sca-1 and cKit (LSK; Figure 4C). We then applied the opposite gating strategy to compare the expression levels of Pcgf1 in different HSPC populations (Figure 4D-E and supplemental Figure 4). Consistent with our qRT-PCR data, Pcgf1 was expressed at higher levels in the Lin− fraction (Figure 4E). The HSC fraction was negative for Pcgf1-eGFP, whereas eGFP was expressed in roughly 50% of MPCs. Only approximately 20% of common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) showed Pcgf1-eGFP expression, whereas approximately half of the GMPs and megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitors (MEPs) were positive. High eGFP-Pcgf1 levels were also detected in common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs). Within the Lin+ fraction, Pcgf1-eGFP was mostly detected in immature erythrocytes and macrophages in the BM, whereas mature macrophages and erythrocytes from the peripheral blood were Pcgf1-eGFP− (supplemental Figure 5).

We conclude that, within the hematopoietic system, Pcgf1 expression is most prominent in myeloid and lymphoid progenitor cells, but is significantly less prominent in HSCs and in mature cells. This finding implies that Pcgf1 functions mainly in HPCs.

Gene-expression analysis identifies Pcgf1 as a repressor of HoxA genes in Lin− cells

As a member of the BCOR/BCORL1 complex, Pcgf1 might participate in gene repression by ubiquitination of histone H2A.21 To investigate a possible repressor role of Pcgf1 in hematopoietic cells and to identify factors that lead to the increased replating capacity due to Pcgf1 depletion, we generated gene-expression profiles using microarrays of Runx1Δ/Δ Lin− cells transduced with a Pcgf1-specific or a control shRNA. Immunophenotyping of transduced cells revealed no marked changes between control and Pcgf1 shRNA–transduced cells, showing that the measured gene-expression changes do not primarily arise from a shift in cell populations during ex vivo culture (supplemental Figure 6A).

Data from 4 independent experiments are summarized in the volcano blot in Figure 5A. Consistent with its role as a transcriptional repressor, Pcgf1 knockdown led to the significant up-regulation of 60 genes. Concurrently, 54 genes were down-regulated in Pcgf1-deficient cells, possibly because of secondary effects of the knockdown or an unknown gene-activating function of Pcgf1. Interestingly, members of the HoxA gene cluster were highly enriched among the most differentially expressed genes (Figure 5A and supplemental Figure 6B). Cdkn2a, a prominent target of polycomb group complexes, was slightly reduced by Pcgf1 knockdown (data not shown). To investigate Hox clusters in more detail, we performed hierarchical cluster analysis of Hox genes present on the microarray chip. The HoxA cluster genes HoxA4, HoxA5, HoxA7, HoxA9, and HoxA10 assembled at the top of the analysis, whereas genes from other Hox clusters were less prominently altered (Figure 5B). qRT-PCR of individual HoxA genes after Pcgf1 knockdown confirmed up-regulation of HoxA4, HoxA5, HoxA7, HoxA9, and HoxA10 (Figure 5C), most of which are known to increase the self-renewal capacity of immature hematopoietic cells.29,33-37 ChIP analysis on HoxA gene promoters of Lin− BM cells expressing Pcgf1-eGFP revealed specific binding of Pcgf1 to the promoters of HoxA7, HoxA9, and HoxA10 (Figure 6A). Consistent with a role of Pcgf1 in chromatin modulation as part of the BCOR/BCORL1 complex, ubiquitination of H2AK119 was compromised at these promoters in the absence of Pcgf1 (Figure 6B). Therefore, these data suggest that Pcgf1 regulates self-renewal by down-regulating multiple genes of the HoxA cluster in HPCs.

Pcgf1 regulates genes of the HoxA cluster. (A-B) Expression analyses of lineage-depleted BM cells from 4 different Runx1Δ/Δ mice isolated and transduced with Pcgf1 (shPcgf1) or control (shCtrl) shRNA are presented. (A) Normalized gene expression in samples with a Pcgf1 knockdown versus control samples in log2 scale is plotted against its P value (−log10). Blue dots display significant differentially regulated genes. Red circles mark selected HoxA cluster genes and Pcgf1. (B) Hierarchical cluster analysis of the 4 mice (experiments 1-4) revealed the up-regulation of several Hox genes on Pcgf1 knockdown (blue indicates down-regulation; red, up-regulation). (C) qRT-PCR analysis of selected HoxA genes in cells transduced with Pcgf1 shRNA compared with control shRNA-transduced cells. After transduction, cells were selected for puromycin resistance for 48 hours, and then total mRNA was isolated and Hox gene expression was analyzed with specific primers. RNA levels of indicated genes were normalized against β-actin. Mean values from 3 independent experiments and the corresponding SDs are shown. Significance of changes in shPcgf1 versus control transduced samples was determined using the Student t test. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Pcgf1 regulates genes of the HoxA cluster. (A-B) Expression analyses of lineage-depleted BM cells from 4 different Runx1Δ/Δ mice isolated and transduced with Pcgf1 (shPcgf1) or control (shCtrl) shRNA are presented. (A) Normalized gene expression in samples with a Pcgf1 knockdown versus control samples in log2 scale is plotted against its P value (−log10). Blue dots display significant differentially regulated genes. Red circles mark selected HoxA cluster genes and Pcgf1. (B) Hierarchical cluster analysis of the 4 mice (experiments 1-4) revealed the up-regulation of several Hox genes on Pcgf1 knockdown (blue indicates down-regulation; red, up-regulation). (C) qRT-PCR analysis of selected HoxA genes in cells transduced with Pcgf1 shRNA compared with control shRNA-transduced cells. After transduction, cells were selected for puromycin resistance for 48 hours, and then total mRNA was isolated and Hox gene expression was analyzed with specific primers. RNA levels of indicated genes were normalized against β-actin. Mean values from 3 independent experiments and the corresponding SDs are shown. Significance of changes in shPcgf1 versus control transduced samples was determined using the Student t test. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Pcgf1 binds to promoters of HoxA genes and promotes their ubiquitination. (A) ChIP was performed using Lin− BM from Pcgf1-eGFP or control mice. DNA was pulled down with an Ab specific for eGFP, and the abundance of HoxA7, HoxA9, and HoxA10 promoter DNA was compared in these 2 samples by qRT-PCR. For HoxA7 and HoxA10, 2 different primer pairs were used. (B) Lin− cells transduced with Pcgf1 (shPcgf1) or control shRNA (shCtrl) were subjected to ChIP using an Ab that recognizes ubiquitinated histone 2A (H2A K119ubi). Binding to Hox promoters was compared between samples by qRT-PCR with the indicated primers. Significance of changes was determined using the Student t test. *P < .05; **P < .01. n.d. indicates not detectable.

Pcgf1 binds to promoters of HoxA genes and promotes their ubiquitination. (A) ChIP was performed using Lin− BM from Pcgf1-eGFP or control mice. DNA was pulled down with an Ab specific for eGFP, and the abundance of HoxA7, HoxA9, and HoxA10 promoter DNA was compared in these 2 samples by qRT-PCR. For HoxA7 and HoxA10, 2 different primer pairs were used. (B) Lin− cells transduced with Pcgf1 (shPcgf1) or control shRNA (shCtrl) were subjected to ChIP using an Ab that recognizes ubiquitinated histone 2A (H2A K119ubi). Binding to Hox promoters was compared between samples by qRT-PCR with the indicated primers. Significance of changes was determined using the Student t test. *P < .05; **P < .01. n.d. indicates not detectable.

In vivo self-renewal capacity of Pcgf1-depleted Runx1Δ/Δ Lin− cells

To test the behavior of Lin− cells lacking Runx1 and Pcgf1 in vivo, we transplanted these cells into lethally irradiated C57BL/6 wild-type mice or Rag2−/−γc−/−KitWv/Wv mice.25 Because of a mutation in the cKit receptor in Rag2−/−γc−/−KitWv/Wv mice, opening of the stem cell niche by irradiation is not necessary. Experiments were carried out under both competitive conditions using unsorted cells or under noncompetitive conditions with cells sorted for the presence of shRNA by an eGFP marker on the same retroviral construct. To determine the engraftment capacity of donor cells, recipient mice were analyzed for expression of eGFP in the peripheral blood and BM.

Before transplantation, cells had comparable transduction efficiencies within the same experiment (supplemental Figure 7A). Surprisingly, despite their strong potential to self-renew in vitro, Runx1Δ/Δ Lin− cells carrying a Pcgf1 shRNA could not be found in the BM of recipient mice within 2-6 months after transplantation (supplemental Figure 7B). The same result was obtained for Runx1Δ/Δ Lin− cells that had been transduced with a control shRNA. In contrast, cells isolated from Runx1fl/fl Lin− cells transduced with control or Pcgf1 shRNA successfully engrafted in recipient mice in most of the experiments. Similar observations were made in the peripheral blood 5-7 weeks after transplantation and shortly before killing the animals (supplemental Figure 7C-D). Pcgf1 knockdown alone generally did not influence the ratios of HSCs, progenitors, and mature blood cells. Only in a few transplanted mice could an increase of GMPs be observed (supplemental Figure 8).

Discussion

HSCs need to manage 2 opposing programs: regeneration of all types of blood cells by differentiation and, at the same time, permanent self-renewal to maintain a constant stem cell pool in the BM. Both programs are controlled by an interactive network of transcription factors and epigenetic regulators to ensure robust hematopoiesis. Although numerous factors involved in this process, including Runx1, have been characterized, we are only beginning to understand the complex interplay between the different parameters.

In the present study, we present a pooled, genome-wide, shRNA-based screen in primary mouse hematopoietic cells to search for genetic interactors of Runx1. To our knowledge, this is one of the first reported genetic interaction screens carried out in primary mammalian cells. By screening for factors that regulate self-renewal and differentiation in Lin− cells together with Runx1, we have uncovered a previously unknown role of the polycomb group protein Pcgf1 in hematopoiesis. In Lin− hematopoietic cells, knockdown of Pcgf1 alone leads to an increased self-renewal capacity as assessed in methylcellulose-replating assays. A similar effect can be observed in Runx1Δ/Δ Lin− cells transduced with a control shRNA. Strikingly, a simultaneous depletion of Runx1 and Pcgf1 virtually immortalizes hematopoietic cells in the same assay. Therefore, the lack of both factors together leads to a strong increase in self-renewal, whereas differentiation is blocked.

The effect of Runx1 on differentiation of hematopoietic cells has been described previously.2-5 To explore possible effects on self-renewal, in the present study, we investigated gene-expression profiles of Pcgf1-depleted Lin− cells and found altered expression of numerous genes, which likely contributes to the enhanced replating phenotype. In particular, Pcgf1 knockdown significantly increased the expression of the posterior HoxA cluster genes HoxA7, HoxA9, and HoxA10, and, to a lesser extent, of the anterior Hox genes HoxA4 and HoxA5. Furthermore, our data show that Pcgf1 binds to the promoters of HoxA7, HoxA9, and HoxA10 and leads to an altered chromatin structure at these promoters. Genes of the HoxA cluster are mainly expressed during early steps of hematopoiesis and are down-regulated during the course of maturation.33-37,40,41 Similar to our observations with Pcgf1 knockdown, overexpression of HoxA4, HoxA9, and HoxA10 leads to an increased plating capacity of Lin− cells in methylcellulose.29 This finding points to a role in self-renewal of these Hox genes. In vivo, overexpression of HoxA9 increases the pool of HSCs and MPCs and shifts differentiation toward myelopoiesis over lymphopoiesis.36 HoxA10 overexpression in a mouse model leads to an increase of MPC numbers and late-onset leukemia.37 Considering the multiple roles of Hox genes during self-renewal and fate decisions of stem and progenitor cells, the effect of Pcgf1 knockdown on the self-renewal of hematopoietic cells likely means that Pcgf1 is required for the down-regulation of several HoxA cluster genes, explaining the observed phenotype of extended growth of HSPCs in methylcellulose.

Consistent with the finding that HoxA genes are down-regulated during the course of hematopoiesis, we found that Pcgf1 was not expressed in HSCs, but rather in HPCs including GMPs, megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitors, and common lymphoid progenitors. In contrast, the Pcgf1 homolog BMI-1 mainly acts in HSCs by promoting self-renewal.24,42 It is therefore possible that the composition and function of the PRC1 complex varies between different stages of hematopoiesis with the expression of different psc homologs. Opposing effects of different variants of PRC1 have been described previously.43,44 For example, another psc homolog, Mel-18, is found predominantly at later stages of differentiation and has the opposite effect on differentiation as BMI-1.42,44,45 Whether Mel-18 exerts its role simultaneously or downstream of Pcgf1 remains to be elucidated. In summary, the presence of several PRC1 complex variants regulated by the expression of psc homologs during different stages of maturation is a tempting hypothesis to explain multiple roles of the PRC1 complex.

Leukemic transformation is often triggered by a differentiation block accompanied by enhanced self-renewal.46 Because cells lacking Runx1 and Pcgf1 display exactly these features, we tested their leukemic potential in transplantation experiments. Unexpectedly, we did not observe the development of leukemia in recipient mice. However, Runx1-knockout cells revealed a poor engraftment potential that was independent of the transduced shRNA. This observation could have been due to a defect in homing of Runx1Δ/Δ cells, as described previously,38 to the lack of survival in the BM niche, or to an exhaustion of the transplanted stem cell pool described previously for Runx1Δ/Δ cells.38,39 Interestingly, a recent study identified CXCR4 and CD49b, factors that are crucial for the interaction of HSCs with the BM niche, as Runx1 target genes, providing a possible explanation for the low engraftment potential of Runx1Δ/Δ HSPCs.38 Therefore, the multiple roles of Runx1 in HSPCs seem to complicate in vivo studies using engraftment experiments. The hypothesis that simultaneous depletion of Runx1 and Pcgf1 might lead to leukemia merits future investigation.

During the revision of this manuscript, 2 studies were published on the impact of members of the BCOR/BCORL1 complex on leukemia. Grossmann et al47 detected BCOR mutations in AML patients with a normal karyotype, and in a similar study in AML patients,48 the BCOR homolog BCORL1 was also found to be mutated. Both proteins interact physically with Pcgf1, and we show in the present study that BCORL1 depletion phenocopied the effects of Pcgf1 knockdown. Interestingly, whereas BCOR/BCORL1 mutations were mutually exclusive with NPM1 mutations, Runx1 mutations were found frequently, possibly reflecting in vivo cooperativity of BCOR/BCORL1 with Runx1, but not with NPM1 mutations. Based on these findings, we propose that sequencing of the Pcgf1 gene in AML samples is warranted.

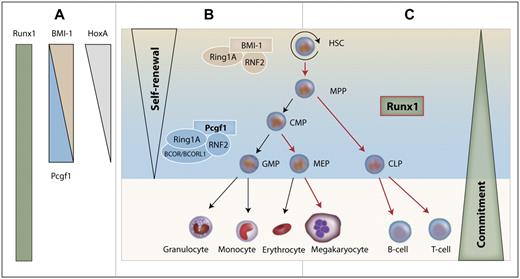

Integrating our data into the current model of hematopoiesis, we propose that Runx1 and Pcgf1 cooperate in the regulation of HPCs, as illustrated in Figure 7. During differentiation of HSCs to progenitor cells, Pcgf1 levels increase. As a consequence, Pcgf1 terminates the self-renewal program in progenitor cells, presumably by ubiquitinating HoxA gene promoters, thus inhibiting their transcription. At the same time, Runx1 drives the expression of differentiation factors, thereby enabling the maturation of HPCs. Therefore, Pcgf1 might prime HPCs for maturation by epigenetically abrogating self-renewal, allowing Runx1 to drive their differentiation.

Model of the cooperative interaction between Runx1 and Pcgf1 in hematopoiesis. (A) Runx1 is expressed in almost all hematopoietic tissues. HoxA genes and BMI-1 are down-regulated with increasing maturation, whereas the expression of Pcgf1 increases from HSCs to progenitors. (B) The PRC1 complex regulates self-renewal in HSCs while interacting with BMI-1. At the progenitor cell level, the PRC1 core complex together with Pcgf1 shuts down self-renewal in progenitor cells by down-regulating HoxA genes. (C) Runx1 drives the differentiation of cells for which self-renewal has been limited by Pcgf1. Maturation steps that are regulated by Runx1 are marked with red arrows. MPP indicates multipotent progenitor; CMP, common myeloid progenitor; MEP, megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitor; and CLP, common lymphoid progenitor.

Model of the cooperative interaction between Runx1 and Pcgf1 in hematopoiesis. (A) Runx1 is expressed in almost all hematopoietic tissues. HoxA genes and BMI-1 are down-regulated with increasing maturation, whereas the expression of Pcgf1 increases from HSCs to progenitors. (B) The PRC1 complex regulates self-renewal in HSCs while interacting with BMI-1. At the progenitor cell level, the PRC1 core complex together with Pcgf1 shuts down self-renewal in progenitor cells by down-regulating HoxA genes. (C) Runx1 drives the differentiation of cells for which self-renewal has been limited by Pcgf1. Maturation steps that are regulated by Runx1 are marked with red arrows. MPP indicates multipotent progenitor; CMP, common myeloid progenitor; MEP, megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitor; and CLP, common lymphoid progenitor.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ina Nüsslein, Nicolas Berger, and Ingrid de Vries for technical assistance; Roland Naumann and Ina Poser and their teams for generation of the Pcgf1-eGFP mouse line; Julia Jarrells for carrying out the microarray analysis; Jussi Helppi and his team for biomedical services; René Bernards and Roderick Beijersbergen for providing the shRNA library; Vivian Bardwell for the Pcgf1 Ab; and the Buchholz laboratory and Fernando Ugarte for scientific discussions.

This study was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Sonderforschungsbereich 655 (BU1400/3-1) and the Deutsche Krebshilfe (106685).

Authorship

Contribution: K.R. and A.K.S. designed and performed the experiments, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript; G.P.T. designed the screen and performed the experiments; M.P.-R. analyzed the microarray data; A.W.B. performed the microscopy analysis; L.D. performed the ChIP assays; T.G. and K.B. helped with the FACS analysis; N.H. performed the proteomic analysis; M.M., C.W., and C.S. contributed materials and scientific advice; and F.B. designed the study and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for A.K.S. is Cellerant Therapeutics Inc, San Carlos, CA. The current affiliation for G.P.T. is Osiris Therapeutics Inc, Columbia, MD. The current affiliation for N.H. is University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Correspondence: Frank Buchholz, MPI-CBG, Pfotenhauerstr 108, 01307 Dresden, Germany; e-mail: buchholz@mpi-cbg.de.

References

Author notes

K.R. and A.K.S. contributed equally to this work.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal