Abstract

Considerable information has accumulated about components of BM that regulate the survival, self-renewal, and differentiation of hematopoietic cells. In the present study, we investigated Wnt signaling and assessed its influence on human and murine hematopoiesis. Hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) were placed on Wnt3a-transduced OP9 stromal cells. The proliferation and production of B cells, natural killer cells, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells were blocked. In addition, some HSPC characteristics were maintained or re-acquired along with different lineage generation potentials. These responses did not result from direct effects of Wnt3a on HSPCs, but also required alterations in the OP9 cells. Microarray, PCR, and flow cytometric experiments revealed that OP9 cells acquired osteoblastic characteristics while down-regulating some features associated with mesenchymal stem cells, including the expression of angiopoietin 1, the c-Kit ligand, and VCAM-1. In contrast, the production of decorin, tenascins, and fibromodulin markedly increased. We found that at least 1 of these extracellular matrix components, decorin, is a regulator of hematopoiesis: upon addition of this proteoglycan to OP9 cocultures, decorin caused changes similar to those caused by Wnt3a. Furthermore, hematopoietic stem cell numbers in the BM and spleen were elevated in decorin-knockout mice. These findings define one mechanism through which canonical Wnt signaling could shape niches supportive of hematopoiesis.

Introduction

A full understanding of supporting niches is critical for realizing the promise of stem cells and regenerative medicine. In particular, we need to learn what extracellular cues regulate stem cell quiescence versus proliferation and self-renewal versus differentiation. Although controversial and incompletely understood, several studies have suggested that Wnt family molecules regulate hematopoiesis.1,2 Confusion exists about which Wnt ligands elicit particular responses and what cells respond to them.

Contradictory conclusions have been reached from knockout and overexpression experiments. For example, conditional deletion of β- and γ-catenin from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in adult BM had little effect, whereas ablation of β-catenin during fetal life produced defective HSCs.3,4 HSCs with similar abnormalities were found in Wnt3a-targeted mice.5 Studies of mice expressing the Wnt inhibitor Dickkopf-1 (Dkk-1) in osteoblasts also suggested that Wnt ligands are important for maintaining HSC integrity.6 Complicating the definition of mechanisms, many cell types in hematopoietic tissues express an array of Wnt receptors, ligands, and modulating molecules. Two studies have concluded that HSCs could respond directly to purified Wnt3a in defined cultures.7,8 A similar conclusion was reached with recombinant Wnt5a and a fusion protein version of secreted frizzled-related protein 1 (sFRP1).9,10 That hematopoietic cells can be direct targets was also suggested by experiments in which constitutively active β-catenin was artificially expressed. In one model, this treatment made lymphoid or myeloid progenitors lineage unstable and allowed the expansion of multipotential cells in culture.11 Exhaustive HSC proliferation resulted in BM failure when strong β-catenin transgenes were expressed in vivo.12,13

HSCs and progenitors normally reside in supporting niches within the BM, and there is some evidence that Wnt ligands affect nonhematopoietic cells in those sites as well.14-17 This could include mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and various cells derived from them (eg, adipocytes, chondrocytes, osteoblasts, hematopoiesis-supporting MSCs, and CXCL12-abundant reticular cells).18,19 Some experimental designs that were used to conclude that Wnt is dispensable for hematopoiesis assessed effects on stem/progenitors rather than the environment.3,4

In our previous studies examining the role of Wnt signaling in hematopoiesis, OP9 stromal cells were transduced to overexpress a series of Wnt family molecules for coculture with hematopoietic cells.20 The aim was to deliver Wnt ligands in physiologic form with culture conditions that support HSCs and primitive progenitors. However, we noticed that the morphology of OP9 cells and their expression of adhesion molecules were altered in these Wnt-producing stromal cells.21 Other investigators concluded that canonical Wnt signals indirectly affect hematopoiesis via paracrine action on adjacent stromal cells.14-16 Also consistent with this possibility, stromal cells deficient in the transcription factor EBF2 up-regulated sFRP1 and did not support hematopoiesis.22 Although it appeared that sFRP1 inhibited Wnt signaling in this model, it can also function as a Wnt ligand, and other investigators have concluded that sFRP1 plays an essential role in hematopoiesis.10,23 Therefore, roles for Wnts in hematopoiesis need to be better understood with respect to responding cell types.

Most of what is known about the influences of Wnt on hematopoiesis derives from experimental animals, and much less is known regarding human cells.24-27 Marked species differences are known regarding hematopoiesis.28 Potential therapeutic applications require that such species variations be well understood. Therefore, in the present study, we conducted experiments with human and murine hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) in stromal cell coculture models, and found that Wnt molecules could dramatically influence cell division, lineage progression, and differentiation. Whereas hematopoietic cells may themselves be Wnt responsive, we show that the small leucine-rich proteoglycan (SLRP) decorin was strongly induced in stromal cells by Wnt3a and could mediate most of the same responses as Wnt3a. These findings suggest that Wnts may be important for maintaining stem cell niches.

Methods

Origin and isolation of cells

Umbilical cord blood (CB) cells were collected from healthy, full-term neonates immediately after normal delivery. Adult BM cells were collected from hematologically normal donors undergoing hip replacement surgery. All samples were collected after informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki using protocols approved by the Investigational Review Board of the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation. Mononuclear cells were separated with lymphocyte separation medium (Mediatech) and centrifugation. Enrichment of CB and BM CD34+ cells was performed using the CD34 MicroBead Kit (Miltenyi Biotec). Human MSCs were purchased from Lonza and maintained in mesenchymal stem cell growth medium (Lonza). Transduced OP9 stromal cells used in the cocultures have been described previously.20 Hematopoiesis-supporting OP9 cells and MS5 stromal cells were maintained and passaged in αMEM (Invitrogen) containing 10% FCS, 2mM l-glutamine, 100 U/mL of penicillin, and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin.

Mice

C57BL/6 (B6) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory, and RAG-1/GFP reporter knock-in mice (B6 background) were bred and maintained in Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation's Comparative Medicine Center. Decorin-deficient (Dcn−/−) mice (B6 background) have been described previously.29 These mice are in a pure C57BL/6 background because they have been backcrossed to that strain for at least 11 generations. The mice were housed in the animal facility of Thomas Jefferson University. Seven- to 15-week-old mice were used for these studies. All experimental procedures were conducted under approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocols.

Flow cytometric analyses and sorting

Flow cytometric analysis and sorting were performed using standard multicolor immunofluorescent staining protocols with a FACS LSRII flow cytometer and a FACSAria cell sorter (both BD Biosciences) or a MoFlo high-speed sorter (Dako Cytomation), respectively. FlowJo Version 7.65 software (TreeStar) was used for data analysis. For the Abs used, see supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Human staining reagents.

For culture experiments, cells were sorted into specific subsets within the lineage marker (glycophorin A [GPA], CD13, CD14, CD19, CD20, CD3, CD8, or CD56)–negative CD34+ population after enrichment of CD34+ cells.

Murine staining reagents.

The indicated Abs were used for flow cytometric sorting and analysis. Abs to CD19, CD45R/B220, CD11b/Mac1, Gr1, Ter119, NK1.1, CD3, and CD8 were used as lineage markers. For isolation of the HSPC population, BM cells were incubated with Abs to CD19 (1D3), CD45R/B220 (14.8), CD11b/Mac1 (M1/70), Gr1 (RB6-8C5), Ter119, and CD8 (53-6.7), followed by the magnetic separation of positively labeled cells with the BioMag goat anti–rat IgG system (QIAGEN). These Lin−-enriched cells were stained with indicated Abs for sorting. To sort stromal cells such as endothelial cells, MSCs, and osteoblasts from BM or spleen, BM and crushed bone fragments of femurs, tibias, humeri, pelvises, and vertebrae or disrupted spleens were incubated at 37°C with type IV collagenase (2 mg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) and DNase (5 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) in HBSS and gently agitated for 60 minutes. The dissociated cells were collected and erythrocytes were lysed in 150mM NH4Cl hypotonic solution. Subsequently, negative selection of hematopoietic lineage markers was conducted before sorting using a FACSAria cell sorter (BD Biosciences).

Cultures for human HSPCs and MSCs

For cocultures of CD34+ cells, stromal cells were plated the day before, and sorted cells were seeded under the indicated cytokine conditions.30 Half of the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium containing the same cytokines twice a week. After the indicated times of culture, cells were counted and subjected to flow cytometry for identification and analysis. For distinguishing cultured hematopoietic cells from stromal cells, fluorescence-labeled anti-CD45 Ab was used. In some experiments, 0.45-μm polyethylene terephthalate membranes (Falcon Cell Culture Inserts; Becton Dickinson Labware) were used to prevent direct contact between OP9 stromal cells and cultured cells. To study de-differentiation capacity, the indicated lymphoid progenitors were sorted and initially cultured on Wnt3a-transduced OP9 stromal cells for 3 days, separated from stromal cells by cell sorting, and put in stromal cell–free erythroid culture supporting medium. Stromal cell–free cultures were usually maintained in QBSF60 medium (Quality Biologic) containing 10% FCS, 100 U/mL of penicillin, and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin with the indicated cytokines. Half of the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium containing the same cytokines twice a week. Recombinant human IL-7, IL-15, SCF, Flk-2 ligand (FL), G-CSF, erythropoietin (EPO), and Wnt3a proteins were purchased from R&D Systems. The cytokines were used at the following concentrations: IL-7, 5 ng/mL; IL-15, 10 ng/mL; SCF, 10 ng/mL; FL, 5 ng/mL; G-CSF, 10 ng/mL; EPO, 5 U/mL; and Wnt3a, 100 ng/mL.

To analyze VCAM-1 expression on MSCs, MSCs were cultured with Wnt3a-transduced OP9 stromal cells or recombinant Wnt3a (100 ng/mL) for 3 days. TNFα at 10 ng/mL (R&D Systems) was added for the first 24 hours to boost VCAM-1 expression. All cultures were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2–humidified atmosphere.

Cultures for murine HSPCs

The indicated populations were sorted and seeded onto monolayers of transduced OP9 stromal cells. These cocultures were maintained in αMEM containing 10% FCS, 2mM l-glutamine, 5 × 10−5 M β-ME, 100 U/mL of penicillin, and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin in the presence of SCF (20 ng/mL), FL (5 ng/mL), and IL-7 (1 ng/mL) for the indicated times. For 2-step cultures, cells were isolated from stromal cells after a 3-day coculture and put in the stromal cell–free erythroid permissive medium (STEM PRO-34 SFM; Invitrogen), 10% FCS, 2mM l-glutamine, 5 × 10−5 M β-ME, 100 U/mL of penicillin, and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin supplemented with 100 ng/mL of TPO, 20 ng/mL of SCF, 50 ng/mL of FL, and 5 U/mL of EPO). For some experiments, the proteoglycan form of recombinant murine decorin (40 μg/mL) was added. All recombinant proteins were from R&D Systems.

To evaluate B-lineage development under stromal cell–free, serum-free conditions, sorted cells were cultured in X-VIVO 15 medium (Lonza) containing 1% detoxified BSA (StemCell Technologies), 5 × 10−5 M β-ME, 100 U/mL of penicillin, and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin in the presence of 20 ng/mL of SCF, 100 ng/mL of FL, and 2 ng/mL of IL-7 for the indicated times. Half of the culture medium was replaced biweekly with fresh medium plus cytokines.

To analyze myeloerythroid potential, IMDM-based methylcellulose medium (MethoCult GF M3434; StemCell Technologies) was used. BM cells (100 of each indicated subset) or 2.5 × 105 splenocytes were seeded into 3.5-cm dishes and recovered colonies were counted and classified according to shape and size under an inverted microscope after 8-11 days of culture.

Microarray analyses

Samples were lysed using SuperAmp Lysis Buffer (Miltenyi Biotec), and RNA amplification and hybridization were performed according to the manufacturer's protocols. Gene-expression analysis using an Agilent Whole Mouse Genome Oligo Microarray was performed by Miltenyi Biotec. Differentially expressed genes were selected by the use of 2 criteria: value of P < .001 defined by the signal intensities and changes greater than 2-fold. The microarray data have been deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (National Center for Biotechnology Information) and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE30791 at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/.

Real-time quantitative PCR analyses of gene expression

Semiquantitative and real-time RT-PCR were used to assess mRNA expression. Reactions were quantified with fluorescent TaqMan technology. TaqMan primers and probes specific for the indicated or GAPDH genes were used in the ABI PRISM 7500 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). Real-time PCR to assess the expression of Wnt-related genes on OP9 vector control and Wnt3a-transduced OP9 was done using preoptimized SYBR-Green 96-well plate pathway specific RT2 profiler primer-array (SABiosciences). mRNAs from samples were isolated using RNeasy Mini Kits (QIAGEN). The cDNAs were then prepared from DNase I-treated mRNA using oligo(dT) and Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen).

Statistical analyses

Student t tests were performed to assess statistical differences. All results are shown as mean values ± SD.

Results

Canonical Wnt signaling blocks human lymphopoiesis, retains an HSPC phenotype, and inhibits proliferation of progenitors and makes them lineage unstable

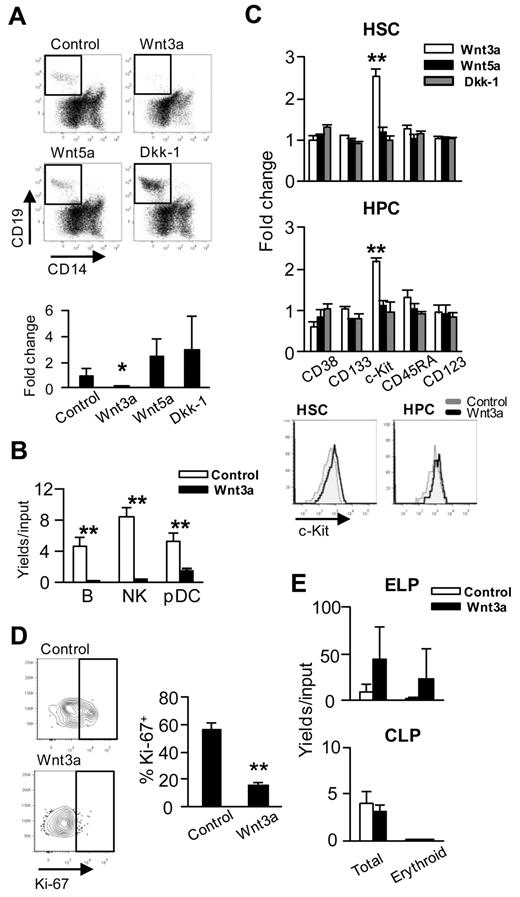

Most of what is known about Wnt regulation of hematopoiesis pertains to experimental models; therefore, we investigated several parameters with human stem/progenitors. As in our previous studies, transduced OP9 cells were used as the source of Wnt ligands.20 Production of CD19+ B-lineage lymphocytes from CD34+CD38− HSCs was almost completely blocked by Wnt3a and enhanced by Wnt5a or Dkk-1 (Figure 1A). In addition, Wnt3a consistently inhibited production of natural killer and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (Figure 1B). The generation of conventional dendritic cells was inhibited in only 2 of 5 experiments (data not shown).

Four aspects of human hematopoiesis are altered by Wnt3a. (A) Human Lin−CD34+CD38− BM cells (15 000 cells/well) were cocultured with Wnt-related gene (ie, Wnt3a, Wnt5a, or Dkk-1)–transduced OP9 cells for 3 weeks under B-lineage supporting conditions (ie, IL-7, SCF, and FL). Flow cytometry was used to evaluate differentiation and representative gating for CD14−CD19+ lymphocytes is shown in the top panels. The fold changes of recovered CD19+ cells numbers to control are given in the bottom panel. (B) CB CD34+ cells were cocultured for 17 days with Wnt3a-producing OP9 cells in the presence of IL-7, SCF, FL, and IL-15. The numbers of B cells (CD14− CD19+), natural killer cells (CD14−CD56+), and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (CD14−CD11c−CD19−CD56−CD123+) recovered were used to calculate yields per input cells. (C) Lin−CD34+CD38− HSCs or Lin−CD34+CD38+ HPCs were sorted from BM and cocultured on Wnt (ie, Wnt3a, Wnt5a, or Dkk-1)–producing OP9 cells for 48-72 hours under cytokine-free conditions to evaluate changes in phenotypes. The 2 bottom panels illustrate retention of c-Kit as reflected in mean fluorescent intensity normalized to control values. (D) The same culture conditions were used to investigate proliferative status, and repre-sentative staining for Ki-67 is shown. Averages ± SD are given in the right panel. (E) A 2-step culture system was used to assess de-differentiation of CB ELPs (Lin−CD34+CD38−CD7+) or CLPs (Lin−CD34+CD38+CD10+). After coculture on OP9-Wnt3a with IL7, SCF, and FL for 3 days, their potential to generate glycophorin-positive erythroid cells during an additional 2 weeks under stromal cell–free, erythropoiesis-supporting conditions (ie, EPO, SCF, and FL) was determined. Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments using ELPs and CLPs isolated from either CB or BM. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired 2-tailed t test analysis. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Four aspects of human hematopoiesis are altered by Wnt3a. (A) Human Lin−CD34+CD38− BM cells (15 000 cells/well) were cocultured with Wnt-related gene (ie, Wnt3a, Wnt5a, or Dkk-1)–transduced OP9 cells for 3 weeks under B-lineage supporting conditions (ie, IL-7, SCF, and FL). Flow cytometry was used to evaluate differentiation and representative gating for CD14−CD19+ lymphocytes is shown in the top panels. The fold changes of recovered CD19+ cells numbers to control are given in the bottom panel. (B) CB CD34+ cells were cocultured for 17 days with Wnt3a-producing OP9 cells in the presence of IL-7, SCF, FL, and IL-15. The numbers of B cells (CD14− CD19+), natural killer cells (CD14−CD56+), and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (CD14−CD11c−CD19−CD56−CD123+) recovered were used to calculate yields per input cells. (C) Lin−CD34+CD38− HSCs or Lin−CD34+CD38+ HPCs were sorted from BM and cocultured on Wnt (ie, Wnt3a, Wnt5a, or Dkk-1)–producing OP9 cells for 48-72 hours under cytokine-free conditions to evaluate changes in phenotypes. The 2 bottom panels illustrate retention of c-Kit as reflected in mean fluorescent intensity normalized to control values. (D) The same culture conditions were used to investigate proliferative status, and repre-sentative staining for Ki-67 is shown. Averages ± SD are given in the right panel. (E) A 2-step culture system was used to assess de-differentiation of CB ELPs (Lin−CD34+CD38−CD7+) or CLPs (Lin−CD34+CD38+CD10+). After coculture on OP9-Wnt3a with IL7, SCF, and FL for 3 days, their potential to generate glycophorin-positive erythroid cells during an additional 2 weeks under stromal cell–free, erythropoiesis-supporting conditions (ie, EPO, SCF, and FL) was determined. Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments using ELPs and CLPs isolated from either CB or BM. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired 2-tailed t test analysis. *P < .05; **P < .01.

CD34+CD38− HSCs or CD34+CD38+ hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) express c-Kit, and densities of this receptor normally decline in lineage progression. In contrast to the other 4 markers, the expression of c-Kit remained high when HSCs and HPCs were cultured for 2 days on Wnt3a-producing OP9 cells (Figure 1C). This response was specific to Wnt3a, because Wnt5a and Dkk-1 had no influence on c-Kit levels.

In short-term cultures, most HPCs enter the cell cycle or continue to proliferate. In contrast, HPCs cocultured with Wnt3a-expressing OP9 cells were quiescent, as reflected in decreased staining with the Ki-67 nuclear antigen (P < .01, Figure 1D).

Two categories of lymphoid progenitors were sorted from CB and assessed for their potential to be reprogrammed. Lin−CD34+CD38−CD7+ early lymphoid progenitors (ELPs) or Lin−CD34+CD38+CD10+ common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs) were placed on OP9 cells transduced with control vector or Wnt3a for 3 days under conditions favorable for B lymphopoiesis.31 There is some controversy concerning primitive lymphoid progenitors in humans.31,32 However, the CD34+CD38−CD7+ fraction of CB that we used as the human equivalent of murine ELPs has been shown to produce only lymphoid lineage cells. Wells were then harvested, and sorted human CD45+ hematopoietic cells were placed under stromal cell–free, erythropoiesis-supporting conditions for an additional 2 weeks. The ELPs expanded well and generated GPA+CD14−CD19− erythroid cells, whereas CLPs could not be reprogrammed in this way (Figure 1E).

These 4 responses to canonical Wnt signaling have previously been recorded with murine stem/progenitor cells,20 and we can now conclude that they are conserved.

Canonical Wnt influences on human hematopoiesis are stromal cell dependent

There are reports that purified HSCs can respond directly to Wnt ligands.7-9,26 In support of that notion, we found that levels of Axin2 and Wisp1 Wnt target gene transcripts increased when murine HSCs were cultured on OP9-Wnt3a cells (data not shown). However, stromal cell participation in Wnt responses was suggested in previous studies,14-16 and we found that expression of adhesion molecules by OP9 cells is altered by Wnt3a.21

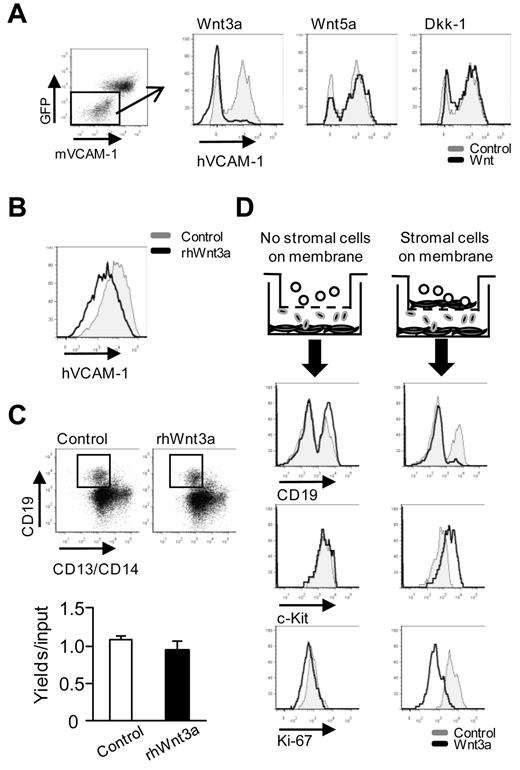

To address the issue of target cells, primary MSCs from human BM were cocultured with transduced OP9 cells with TNFα included to boost levels of VCAM-1. This approach revealed that human VCAM-1 expression was suppressed by Wnt3a, but not Wnt5a- or Dkk-1–producing OP9 cells (Figure 2A). We then added recombinant human Wnt3a to human MSC cultures and determined that at least some loss of VCAM-1 expression was not dependent on OP9 cells (Figure 2B).

Wnt3a regulates human hematopoiesis via stromal cells. (A) Human MSCs were cocultured with Wnt (ie, Wnt3a, Wnt5a, or Dkk-1)–transduced OP9 cells for 3 days, with recombinant human TNFα present for the first 24 hours to enhance VCAM-1 expression. (B) MSCs were similarly cultured along with recombinant human Wnt3a. Flow cytometry histograms of VCAM-1 staining are shown. (C) BM CD34+ cells were cultured without stromal cells for 3 weeks under B-lineage conditions (G-CSF and SCF). The numbers of recovered CD19+ cells are given in the panel below. (D) An experimental design was used to determine whether direct contact between hematopoietic cells and stromal cells was required. The top figure in each row depicts the experimental design, whereas the next shows results from a 4-week culture of CD34+ cells under lymphoid conditions. The bottom 2 rows show results of 2-day cytokine-free cultures initiated with CD34+ cells. Suppressed B lymphopoiesis (expression of CD19), retention of c-Kit, and diminished replication (Ki-67 staining) all required that stromal cells were present in the top chambers. Results from controls are given as gray lines, and those for OP9-Wnt3a are shown as black lines. Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments using either CB or BM together with MS5 or OP9 stromal cells in the top chambers. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired 2-tailed t test analysis: **P < .01.

Wnt3a regulates human hematopoiesis via stromal cells. (A) Human MSCs were cocultured with Wnt (ie, Wnt3a, Wnt5a, or Dkk-1)–transduced OP9 cells for 3 days, with recombinant human TNFα present for the first 24 hours to enhance VCAM-1 expression. (B) MSCs were similarly cultured along with recombinant human Wnt3a. Flow cytometry histograms of VCAM-1 staining are shown. (C) BM CD34+ cells were cultured without stromal cells for 3 weeks under B-lineage conditions (G-CSF and SCF). The numbers of recovered CD19+ cells are given in the panel below. (D) An experimental design was used to determine whether direct contact between hematopoietic cells and stromal cells was required. The top figure in each row depicts the experimental design, whereas the next shows results from a 4-week culture of CD34+ cells under lymphoid conditions. The bottom 2 rows show results of 2-day cytokine-free cultures initiated with CD34+ cells. Suppressed B lymphopoiesis (expression of CD19), retention of c-Kit, and diminished replication (Ki-67 staining) all required that stromal cells were present in the top chambers. Results from controls are given as gray lines, and those for OP9-Wnt3a are shown as black lines. Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments using either CB or BM together with MS5 or OP9 stromal cells in the top chambers. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired 2-tailed t test analysis: **P < .01.

As another approach, human HSPCs were cultured under stromal cell–free lymphopoiesis conditions with or without recombinant Wnt3a.33 Generation of human CD19+ lymphocytes was unaffected by this ligand (Figure 2C). Participation of stromal cells was further investigated with a 2-chamber culture model (Figure 2D). Hematopoietic cells were present alone in the upper chamber or together with nontransduced stromal cells. Our goal was to determine whether the diffusible Wnt3a produced in the lower chamber could alter hematopoiesis. B lymphopoiesis and Ki-67 staining were again diminished and c-Kit levels increased when Wnt3a-producing OP9 cells were present, but only when some type of stromal cells were in the same chamber. OP9 or MS5 stromal cells in contact with hematopoietic cells mediated responses to OP9-Wnt3a cells located in the other chamber. We conclude that both hematopoietic and stromal cells are Wnt targets. However, at least some hematopoietic responses require that MSCs be in close proximity.

Mesenchymal stromal cells are significantly altered by Wnt3a

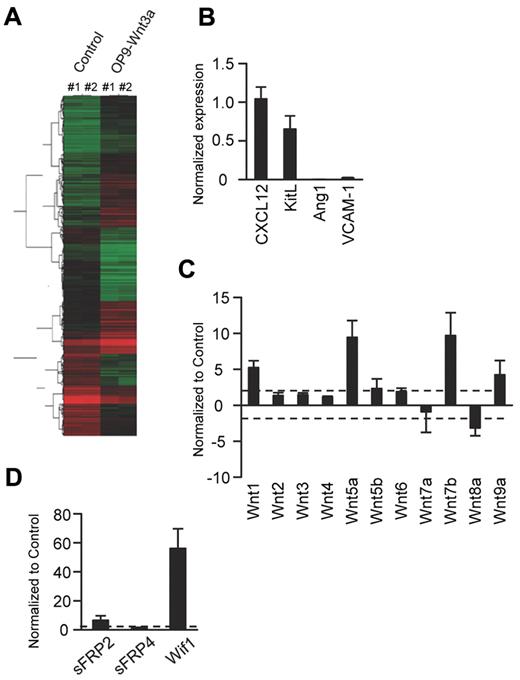

OP9 cells are extensively used in coculture studies, and we wondered how similar they are to generic MSCs.34-37 Flow cytometric analyses revealed OP9 cells to be Sca-1+CD44+PDGFRα+PDGFRβ+CD105low/−CD31−Flk-2−Tie-2− (supplemental Figure 1). Microarray analyses were then conducted to learn more about the basal and Wnt3a-induced characteristics of OP9 cells (Figure 3A). Transcripts for 322 genes, including 4 of 5 previously described Wnt target genes, were significantly up-regulated in Wnt3a-transduced compared with vector control OP9 cells, whereas those for an additional 274 genes were reduced by canonical Wnt signaling (Table 1). Gene ontology analysis of these results revealed that a series of chondrocyte- and adipocyte-associated genes expressed in parent OP9 cells were suppressed, whereas many corresponding to early osteoblastic differentiation were increased. There was no change in the late osteoblast marker osteocalcin.17 Transcripts for PDGFRα and CD90 markers associated with MSCs were also suppressed, and the change in PDGFRα was confirmed by flow cytometry (Table 1 and supplemental Figure 1). These results suggested that OP9 cells transduced with Wnt3a down-regulate from characteristic MSC genes, including a cluster of genes associated with HSC support, including angiopoietin 1 (Ang1), Kit ligand/stem cell factor (KitL), VCAM-1, and CXCL12 (Table 1).19,34,36,38 All of these except CXCL12 were confirmed by quantitative PCR and flow cytometry (Figure 3B and/or supplemental Figure 1). There was also evidence for feedback regulation of Wnt signaling, and this was investigated further with a PCR array (Figure 3C-D). Expression of the canonical Wnt1, Wnt5a, Wnt7b, and Wnt9a ligands increased, as was the case for sFRP2 and Wif1, which may modulate Wnt signaling.

Gene-expression patterns suggest that Wnt3a initiates osteoblastic differentiation of OP9 stromal cells. (A) Microarray analyses were conducted comparing Wnt3a-transduced and vector-transduced OP9 stromal cells. The genes were grouped using a hierarchical clustering technique based on patterns of expression, and the heat map shows the hierarchical relationships. Each column represents results from 2 independent experiments that gave nearly identical results. (B) RT-PCR was then used on freshly isolated mRNA to evaluate the expression of hematopoiesis-supporting genes. (C-D) A PCR array was used to assess expression of Wnt ligands and Wnt modulator genes. The results in each panel represent Wnt3a transduced as fold changes from vector control samples. The direction of changes were similar in 3 independent experiments, and pooled results are given ± SD.

Gene-expression patterns suggest that Wnt3a initiates osteoblastic differentiation of OP9 stromal cells. (A) Microarray analyses were conducted comparing Wnt3a-transduced and vector-transduced OP9 stromal cells. The genes were grouped using a hierarchical clustering technique based on patterns of expression, and the heat map shows the hierarchical relationships. Each column represents results from 2 independent experiments that gave nearly identical results. (B) RT-PCR was then used on freshly isolated mRNA to evaluate the expression of hematopoiesis-supporting genes. (C-D) A PCR array was used to assess expression of Wnt ligands and Wnt modulator genes. The results in each panel represent Wnt3a transduced as fold changes from vector control samples. The direction of changes were similar in 3 independent experiments, and pooled results are given ± SD.

Microarray analysis of Wnt3a-transduced OP9 cells

| . | Symbol . | Sequence description . | Accession no. . | Fold change . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSC | Nes | Nestin | NM_016701 | −1.17 | .362 |

| Eng | Endoglin | NM_007932 | −1.11 | .554 | |

| Pdgfra | Platelet derived growth factor receptor, alpha polypeptide | NM_011058 | −5.69 | <.001 | |

| Thy1 | Thymus cell antigen 1, CD90 | NM_009382 | −2.21 | <.001 | |

| Osteoblastic | Alp | Alkaline phosphatase, liver/bone/kidney | NM_007431 | > 100 | <.001 |

| Runx2 | Runt related transcription factor 2 | NM_009820 | 4.64 | <.001 | |

| Bmp4 | Bone morphogenetic protein 4 | NM_007554 | 2.02 | <.001 | |

| Ogn | Osteoglycin | NM_008760 | 3.22 | <.001 | |

| Sp7 | Sp7 transcription factor 7, osterix | NM_130458 | 22.45 | <.001 | |

| Bglap1 | Bone gamma carboxyglutamate protein 1, osteocalcin | NM_007541 | 1.98 | .020 | |

| Gpnmb | Glycoprotein (transmembrane) nmb, osteoactivin | NM_053110 | 3.85 | <.001 | |

| Pth1r | Parathyroid hormone 1 receptor | NM_011199 | 33.48 | <.001 | |

| Col1a1 | Collagen, type I, alpha 1 | NM_007742 | 4.69 | <.001 | |

| Adipogenic | Cfd | Complement factor D, adipsin | NM_013459 | −1.71 | .230 |

| Pparg | Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma | NM_011146 | −6.53 | <.001 | |

| Fabp4 | Fatty acid binding protein 4, Ap2 | NM_024406 | −13.34 | <.001 | |

| Plin | Perilipin | NM_175640 | −3.07 | <.001 | |

| Chondrogenic | Acan | Aggrecan | NM_007424 | −1.13 | .172 |

| Sox9 | SRY-box containing gene 9 | NM_011448 | −2.96 | <.001 | |

| Col2a1 | Collagen, type II, alpha 1 | NM_031163 | −3.93 | <.001 | |

| Col11a2 | Collagen, type XI, alpha 2 | NM_009926 | −1.26 | .390 | |

| HSC-supportive | Kitl | Kit ligand | NM_013598 | −27.53 | <.001 |

| Vcam1 | Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 | NM_011693 | −10.21 | <.001 | |

| Cxcl12 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 12 | NM_021704 | −4.22 | <.001 | |

| Angpt1 | Angiopoietin 1 | NM_009640 | <−100 | <.001 | |

| Wnt target | Axin2 | Axin2 | NM_015732 | 11.61 | <.001 |

| Myc | Myelocytomatosis oncogene | NM_010849 | 2.48 | <.001 | |

| Bmp4 | Bone morphogenetic protein 4 | NM_007554 | 2.02 | <.001 | |

| Ptgs2 | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 | NM_011198 | 2.14 | .015 | |

| Fn1 | Fibronectin 1 | NM_010233 | 1.07 | .593 | |

| Membrane/ECM protein | Dcn | Decorin | NM_007833 | 57.67 | <.001 |

| Bgn | Biglycan | NM_007542 | −1.18 | .057 | |

| Fmod | Fibromodulin | NM_021355 | > 100 | <.001 | |

| Tnc | Tenascin C | NM_011607 | > 100 | <.001 | |

| Tnn | Tenascin N | NM_177839 | > 100 | <.001 | |

| Tnxb | Tenascin XB | NM_031176 | −10.69 | <.001 | |

| Ncam1 | Neural cell adhesion molecule 1 | NM_010875 | 14.88 | <.001 | |

| Clec11a | C-type lectin domain family 11, member a, stem cell growth factor (SCGF) | NM_009131 | 85.60 | <.001 |

| . | Symbol . | Sequence description . | Accession no. . | Fold change . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSC | Nes | Nestin | NM_016701 | −1.17 | .362 |

| Eng | Endoglin | NM_007932 | −1.11 | .554 | |

| Pdgfra | Platelet derived growth factor receptor, alpha polypeptide | NM_011058 | −5.69 | <.001 | |

| Thy1 | Thymus cell antigen 1, CD90 | NM_009382 | −2.21 | <.001 | |

| Osteoblastic | Alp | Alkaline phosphatase, liver/bone/kidney | NM_007431 | > 100 | <.001 |

| Runx2 | Runt related transcription factor 2 | NM_009820 | 4.64 | <.001 | |

| Bmp4 | Bone morphogenetic protein 4 | NM_007554 | 2.02 | <.001 | |

| Ogn | Osteoglycin | NM_008760 | 3.22 | <.001 | |

| Sp7 | Sp7 transcription factor 7, osterix | NM_130458 | 22.45 | <.001 | |

| Bglap1 | Bone gamma carboxyglutamate protein 1, osteocalcin | NM_007541 | 1.98 | .020 | |

| Gpnmb | Glycoprotein (transmembrane) nmb, osteoactivin | NM_053110 | 3.85 | <.001 | |

| Pth1r | Parathyroid hormone 1 receptor | NM_011199 | 33.48 | <.001 | |

| Col1a1 | Collagen, type I, alpha 1 | NM_007742 | 4.69 | <.001 | |

| Adipogenic | Cfd | Complement factor D, adipsin | NM_013459 | −1.71 | .230 |

| Pparg | Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma | NM_011146 | −6.53 | <.001 | |

| Fabp4 | Fatty acid binding protein 4, Ap2 | NM_024406 | −13.34 | <.001 | |

| Plin | Perilipin | NM_175640 | −3.07 | <.001 | |

| Chondrogenic | Acan | Aggrecan | NM_007424 | −1.13 | .172 |

| Sox9 | SRY-box containing gene 9 | NM_011448 | −2.96 | <.001 | |

| Col2a1 | Collagen, type II, alpha 1 | NM_031163 | −3.93 | <.001 | |

| Col11a2 | Collagen, type XI, alpha 2 | NM_009926 | −1.26 | .390 | |

| HSC-supportive | Kitl | Kit ligand | NM_013598 | −27.53 | <.001 |

| Vcam1 | Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 | NM_011693 | −10.21 | <.001 | |

| Cxcl12 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 12 | NM_021704 | −4.22 | <.001 | |

| Angpt1 | Angiopoietin 1 | NM_009640 | <−100 | <.001 | |

| Wnt target | Axin2 | Axin2 | NM_015732 | 11.61 | <.001 |

| Myc | Myelocytomatosis oncogene | NM_010849 | 2.48 | <.001 | |

| Bmp4 | Bone morphogenetic protein 4 | NM_007554 | 2.02 | <.001 | |

| Ptgs2 | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 | NM_011198 | 2.14 | .015 | |

| Fn1 | Fibronectin 1 | NM_010233 | 1.07 | .593 | |

| Membrane/ECM protein | Dcn | Decorin | NM_007833 | 57.67 | <.001 |

| Bgn | Biglycan | NM_007542 | −1.18 | .057 | |

| Fmod | Fibromodulin | NM_021355 | > 100 | <.001 | |

| Tnc | Tenascin C | NM_011607 | > 100 | <.001 | |

| Tnn | Tenascin N | NM_177839 | > 100 | <.001 | |

| Tnxb | Tenascin XB | NM_031176 | −10.69 | <.001 | |

| Ncam1 | Neural cell adhesion molecule 1 | NM_010875 | 14.88 | <.001 | |

| Clec11a | C-type lectin domain family 11, member a, stem cell growth factor (SCGF) | NM_009131 | 85.60 | <.001 |

Microarray analyses were conducted comparing Wnt3a with vector-transduced OP9 stromal cells, and the average probe intensities from 2 independent samples were used to calculate the -fold change.

These findings show that OP9 stromal cells have many features of MSCs but convert to early osteoblast-like cells when transduced with Wnt3a. Some characteristics associated with hematopoiesis are lost, and autocrine responses include up-regulation of other Wnt family members.

Extracellular matrix proteins are induced by Wnt3a and at least one of them alters hematopoiesis

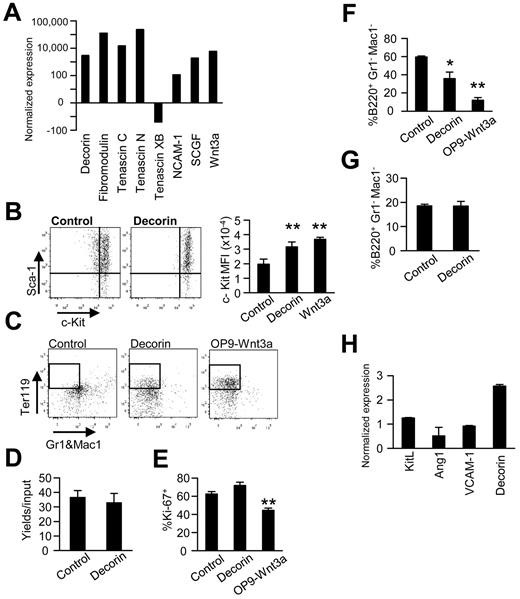

Microarray results were used to identify Wnt3a-regulated molecules that could potentially alter hematopoiesis. Changes in transcripts for a series of transmembrane and secreted proteins were notable because of the magnitude of the change and potential roles in cell-cell communication (Figure 4A). As one example, levels of the SLRP decorin consistently increased more than 3000-fold after Wnt3a induction.

Wnt3a induces expression of matrix molecules, and one of them mediates most Wnt3a-regulated changes in murine hematopoiesis. (A) RT-PCR was performed using Wnt3a-transduced OP9 stromal cells. The results are expressed as the fold changes relative to the vector control OP9 cells and are representative of those obtained in 3 independent experiments. (B) Murine Lin−Sca-1+c-KithiFlk-2− HSCs were then cocultured with decorin plus OP9 or on OP9-Wnt3a in the presence of IL-7, SCF, and FL for 3 days. Levels of c-Kit are shown as typical histograms or mean fluorescence intensities (MFI). (C) Lin−Sca-1+c-KithiRag1-GFP+ ELPs were held for 3 days in primary cultures before subculture in stromal cell–free, erythropoiesis-supporting conditions. After an additional 2 weeks of culture, the generation of Ter119+ erythroid cells was analyzed using flow cytometry. (D) Numbers of Ter119+ erythroid cells were determined by flow cytometry after Lin−Sca-1+c-Kithi cells were held for 2 weeks of culture under stromal cell–free, erythroid-supporting conditions. (E) Proliferation of Lin−Sca-1+c-KithiFlk-2− HSCs was unaffected by decorin, as reflected in Ki-67 staining. (F-G) The influence of recombinant decorin on B lymphopoiesis was tested with 1-week stromal cell cocultures (F) or stromal cell–free cultures (G) initiated with ELPs. Generation of B220+ lymphocytes in triplicate wells ± SD is shown. (H) The same transmembrane culture system shown in Figure 2D was used to analyze gene-expression patterns in OP9 cells exposed to diffusible Wnt3a produced by transduced cells in the lower wells. Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired 2-tailed t test analysis: *P < .05; **P < .01.

Wnt3a induces expression of matrix molecules, and one of them mediates most Wnt3a-regulated changes in murine hematopoiesis. (A) RT-PCR was performed using Wnt3a-transduced OP9 stromal cells. The results are expressed as the fold changes relative to the vector control OP9 cells and are representative of those obtained in 3 independent experiments. (B) Murine Lin−Sca-1+c-KithiFlk-2− HSCs were then cocultured with decorin plus OP9 or on OP9-Wnt3a in the presence of IL-7, SCF, and FL for 3 days. Levels of c-Kit are shown as typical histograms or mean fluorescence intensities (MFI). (C) Lin−Sca-1+c-KithiRag1-GFP+ ELPs were held for 3 days in primary cultures before subculture in stromal cell–free, erythropoiesis-supporting conditions. After an additional 2 weeks of culture, the generation of Ter119+ erythroid cells was analyzed using flow cytometry. (D) Numbers of Ter119+ erythroid cells were determined by flow cytometry after Lin−Sca-1+c-Kithi cells were held for 2 weeks of culture under stromal cell–free, erythroid-supporting conditions. (E) Proliferation of Lin−Sca-1+c-KithiFlk-2− HSCs was unaffected by decorin, as reflected in Ki-67 staining. (F-G) The influence of recombinant decorin on B lymphopoiesis was tested with 1-week stromal cell cocultures (F) or stromal cell–free cultures (G) initiated with ELPs. Generation of B220+ lymphocytes in triplicate wells ± SD is shown. (H) The same transmembrane culture system shown in Figure 2D was used to analyze gene-expression patterns in OP9 cells exposed to diffusible Wnt3a produced by transduced cells in the lower wells. Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired 2-tailed t test analysis: *P < .05; **P < .01.

The addition of stem cell growth factor and neutralizing Abs to either tenascin C or NCAM-1 did not influence c-Kit expression in cocultures (data not shown). However, recombinant decorin altered hematopoiesis in stromal cell cocultures (Figure 4B-F). c-Kit densities were uniformly high on murine HSPCs exposed to decorin in 3-day cultures. The percentages of c-Kithi cells were very similar to those on HSPCs held on Wnt3a-transduced OP9 cells. A possible reprogramming of murine ELPs was then assessed with 2-step cultures (Figure 4C). Decorin-containing cultures were similar to those using Wnt3a/OP9 stromal cells, and Ter119+ erythroid lineage cells were generated in both cases. Using the same stromal cell–free conditions, we found that decorin did not influence erythropoiesis from HSPCs (Figure 4D). In contrast to these responses, cell-cycle status as assessed by Ki-67 staining was unaffected by decorin addition (Figure 4E). B lymphopoiesis was partially blocked when decorin was added to stromal cell cocultures, but no direct response was seen using stromal cell–free cultures (Figure 4F-G). We then used transmembrane cultures to assess the importance of proximity of the responding stromal cells to Wnt3a-producing cells. Diffusible Wnt3a decreased Ang1 expression and increased decorin expression, but no changes in KitL and VCAM1 were found (Figure 4H). This is consistent with our previous findings that Wnt3a-induced changes are more pronounced when responding and producing cells are nearby.21

We conclude that strong decorin production is among a series of Wnt-induced changes in extracellular matrix- and adhesion-related molecules. Recombinant decorin causes some of the hematopoietic changes elicited by Wnt3a, but only in stromal cell–containing cultures.

Decorin is produced by MSCs in BM

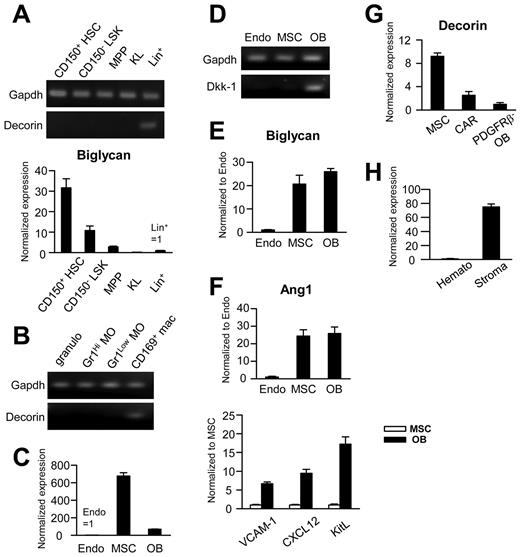

The culture experiments suggested that decorin might function in stem/progenitor niches, so we explored patterns of expression in tissues. Whereas transcripts could be detected in Lin+ cells, this was not the case for any subset of HSCs/HPCs in BM (Figure 5A). In contrast, the closely related proteoglycan biglycan was shown previously to be produced by stem cells.39 CD169+ macrophages have been described recently as regulators of hematopoiesis-supporting niches38 and they also express decorin (Figure 5B).

Decorin is expressed in some putative components of hematopoiesis-supporting niches. Freshly isolated BM cells were sorted into the following populations: Lin−Sca-1+c-Kithi Flk-2− HSCs; Lin− Sca-1+ c-Kithi Flk-2+ Multipotent progenitor (MPPs); Lin− Sca-1− c-Kit+ myeloid progenitors (KL); Gr1+ CD115− granulocytes (granulo); Gr1hi/lowCD115+ monocytes (MO); Gr1−CD115low/−F4/80+CD169+ macrophages (mac); CD45−Ter119−CD31+Sca-1+ endothelial cells (Endo); CD45−Ter119−CD31−CD51+Sca1+ MSCs; CD45−Ter119−CD31−CD51+Sca-1− osteoblasts (OB); and CD45−Ter119−CD31−CD51+Sca-1−PDGFRβ+ CXCL12 abundant reticular cells. For experiment H, CD45+ hematopoietic cells (Hemato) and CD45−Ter119−CD31− nonhematopoietic, nonendothelial cells (Stroma) were sorted from collagenase-treated spleens. Each set of panels represents results from RT-PCR normalized to samples with the smallest signals. When transcripts were detected in only one sample in an experiment, the results are shown as gel images.

Decorin is expressed in some putative components of hematopoiesis-supporting niches. Freshly isolated BM cells were sorted into the following populations: Lin−Sca-1+c-Kithi Flk-2− HSCs; Lin− Sca-1+ c-Kithi Flk-2+ Multipotent progenitor (MPPs); Lin− Sca-1− c-Kit+ myeloid progenitors (KL); Gr1+ CD115− granulocytes (granulo); Gr1hi/lowCD115+ monocytes (MO); Gr1−CD115low/−F4/80+CD169+ macrophages (mac); CD45−Ter119−CD31+Sca-1+ endothelial cells (Endo); CD45−Ter119−CD31−CD51+Sca1+ MSCs; CD45−Ter119−CD31−CD51+Sca-1− osteoblasts (OB); and CD45−Ter119−CD31−CD51+Sca-1−PDGFRβ+ CXCL12 abundant reticular cells. For experiment H, CD45+ hematopoietic cells (Hemato) and CD45−Ter119−CD31− nonhematopoietic, nonendothelial cells (Stroma) were sorted from collagenase-treated spleens. Each set of panels represents results from RT-PCR normalized to samples with the smallest signals. When transcripts were detected in only one sample in an experiment, the results are shown as gel images.

Decorin transcripts were extremely low in CD45−Ter119−CD31+Sca-1+ endothelial cells from normal BM, and slightly higher in CD45−Ter119−CD31−Sca-1−CD51+ osteoblasts. In contrast, transcript levels were 400-fold higher in CD45−Ter119−CD31−Sca-1+CD51+ MSCs (Figure 5C). Transcripts for the Dkk-1 inhibitor of Wnt signaling are known to be restricted to osteoblasts, and these were used to confirm the purity of our MSC/osteoblast sorts (Figure 5D).17 To put these decorin-producing cells in context with ligand responsiveness, a RT-PCR analysis of Wnt receptors was performed (supplemental Figure 2A-B), which revealed that decorin-producing cells express multiple Wnt receptors.

MSCs can reversibly shift between osteoblastic, hematopoiesis-supporting, and adipocyte phenotypes,18,19 so quantitative RT-PCR was then used to better characterize the population of decorin-producing cells. MSCs and osteoblasts were equivalent with respect to biglycan expression and both had high levels of Ang1 (Figure 5E-F). MSCs also had detectable but low levels of transcripts for CXCL12, KitL, and VCAM-1.36

CXCL12 abundant reticular cells are thought to be important components of HSC niches and can be sorted as PDGFRβ+Sca-1−CD51+ (supplemental Figure 2C).19 Even when CXCL12 abundant reticular cells were highly enriched, expression of decorin was low compared with MSCs (Figure 5G). We conclude that MSCs are a major source of decorin in normal BM. Interestingly, we found that nonhematopoietic, nonendothelial (CD45−Ter119−CD31−) stromal cells in the spleen also produced high levels of decorin (Figure 5H).

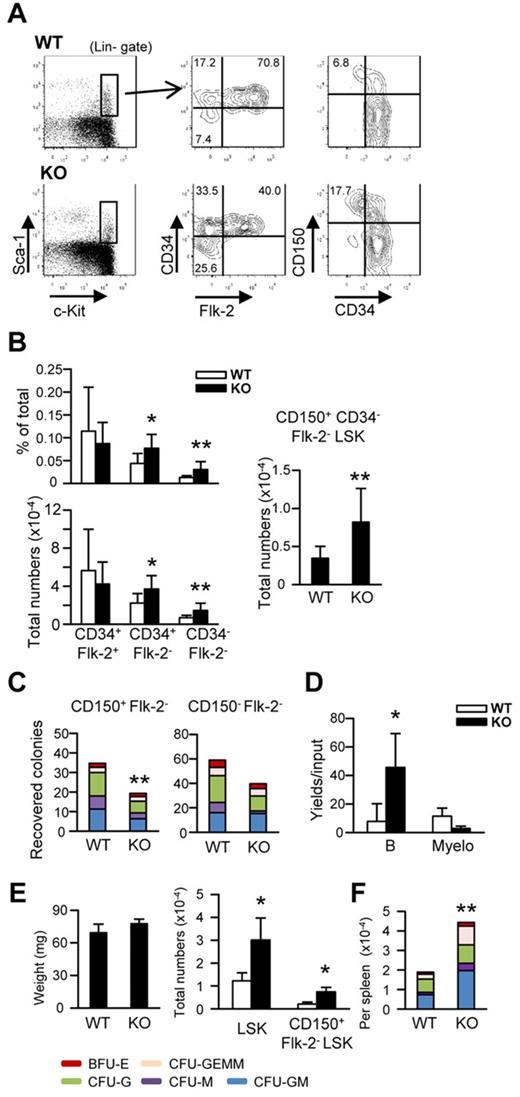

Early stages of hematopoiesis are abnormal in decorin-knockout mice

Decorin-null mice are viable and fertile, but have mild skin fragility because of the importance of decorin in collagen fibril formation.40 The mice can spontaneously develop intestinal tumors and aggressive T-cell lymphomas when the tumor suppressor p53 is concurrently ablated.29,41 Otherwise, the animals appear healthy, and osteoporosis only develops when the biglycan gene is targeted at the same time.40 We conducted a thorough analysis of hematopoietic cells in decorin-knockout mice that were 7-9 weeks old (Figure 6 and supplemental Figure 3). No abnormalities were found with respect to BM cellularity or proportions and numbers of hematopoietic myeloid and lymphoid progenitors. The same was true for more mature myeloid, erythroid, or lymphoid lineage cells. In contrast, numbers of rigorously defined Lin−Sca-1+c-KithiCD34−Flk-2−CD150+ HSCs were elevated an average of 2.2-fold (Figure 6A-B. The hematopoietic potential of these HSCs was reduced when they were cultured in cytokine-containing Methocel cultures, and the same was true for the CD150−Flk-2− fraction of BM (Figure 6C). In contrast, the same primitive subset had increased potential for B-lineage lymphocyte generation in serum-free, stromal cell–free cultures (Figure 6D).

Targeting of the decorin gene expands the numbers of rigorously defined HSCs and extramedullary hematopoiesis. (A-B) BM cells were prepared from 7- to 9-week-old decorin-deficient (KO) and control (WT) mice. Without initial separation, the samples were stained for lineage-associated (Lin) or other surface markers as indicated. The stem/progenitor cell enriched Lin−Sca-1+c-Kithi (LSK) category of cells was subdivided according to Flk-2, CD34, or CD150 expression. Incidences or total numbers of each subset are given in panel B. These represent pooled results using a total of 9 mice of each kind in 3 independent experiments. (C-D) CD150+ or CD150−Flk-2− LSKs were cultured under stromal cell–free, serum-free conditions to analyze myeloerythroid potentials (C) or B-lymphoid potentials from CD150−Flk-2− LSKs (D). Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments. (E) Weights and numbers of LSKs in spleens are given in the left and right panels. (F) Splenocytes were also cultured in cytokine-containing methylcellulose medium for 1 week. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired 2-tailed t test analysis. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Targeting of the decorin gene expands the numbers of rigorously defined HSCs and extramedullary hematopoiesis. (A-B) BM cells were prepared from 7- to 9-week-old decorin-deficient (KO) and control (WT) mice. Without initial separation, the samples were stained for lineage-associated (Lin) or other surface markers as indicated. The stem/progenitor cell enriched Lin−Sca-1+c-Kithi (LSK) category of cells was subdivided according to Flk-2, CD34, or CD150 expression. Incidences or total numbers of each subset are given in panel B. These represent pooled results using a total of 9 mice of each kind in 3 independent experiments. (C-D) CD150+ or CD150−Flk-2− LSKs were cultured under stromal cell–free, serum-free conditions to analyze myeloerythroid potentials (C) or B-lymphoid potentials from CD150−Flk-2− LSKs (D). Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments. (E) Weights and numbers of LSKs in spleens are given in the left and right panels. (F) Splenocytes were also cultured in cytokine-containing methylcellulose medium for 1 week. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired 2-tailed t test analysis. *P < .05; **P < .01.

In addition, some Dcn−/− mice had enlarged spleens with increased numbers of HSCs in the LSK fraction (Figure 6E). Methocel cultures of spleen cells provided another indication of extramedullary hematopoiesis (Figure 6F). Our analysis of gene-targeted mice suggests that decorin regulates the number, lineage preference, and location of HSCs.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrate that canonical Wnt signaling blocks human lymphopoiesis, retains an HSC phenotype, inhibits proliferation, and makes progenitors lineage unstable. These changes were observed when a MSC line was used as the source of Wnt3a and when stromal cells were in close contact with hematopoietic cells. Recombinant Wnt3a had no effect on B lymphopoiesis in stromal cell–free cultures. Therefore, Wnt3a levels must be important for maintaining environmental conditions conducive to hematopoiesis. At least part of that regulation may involve pericellular matrices composed of biologically active proteoglycans such as decorin.

Transcripts for many extracellular matrix and adhesion molecules were modified by Wnt3a overexpression in stromal cells. Of these, decorin was an attractive candidate for further study because of the availability of recombinant protein and gene-targeted mice. Decorin is a multifunctional member of the SLRP family with structural similarity to biglycan.42 The 2 molecules cooperate to regulate survival and proliferation of BM stromal cells.40 Whereas biglycan is constitutively expressed by HSCs,39 we now show that decorin is made by CD45−Ter119−CD31−Sca-1+CD51+ MSCs. The addition of recombinant decorin to stromal cell cocultures modulated c-Kit expression on hematopoietic cells, allowed stromal cell reprogramming of ELPs to an erythroid fate, and partially blocked B lymphopoiesis. With the exception of cell-cycle status, which was unchanged, these responses match those resulting from Wnt3a overexpression. Furthermore, HSC numbers were increased in the BM of decorin-deficient mice and mobilized to the spleen.

The SLRP family of molecules may regulate hematopoiesis via multiple mechanisms. For example, decorin can regulate cell growth by binding and down-regulating receptor-type tyrosine kinases.42 Ligation of the Met receptor reduces β-catenin and levels of the Wnt target cMyc.43 The 3000-fold increase observed in decorin transcript levels with Wnt3a stimulation suggests a mechanism for negative feedback regulation. However, we have as yet identified no responses of purified hematopoietic or stromal cells to recombinant decorin. For example, B lymphopoiesis was not suppressed by decorin in stromal cell–free cultures (Figure 6D), and CXCL12, Ang1, KitL, and VCAM-1 were unchanged in decorin-treated stromal cells. Furthermore, MSCs sorted from decorin-knockout mice appeared to be normal for the same parameters (data not shown). Decorin is well known for its ability to bind and neutralize TGF-β,44 a cytokine that could target both of these cell types. However, this would not explain why stromal and hematopoietic cells need to be in contact for hematopoiesis to be altered. Decorin is a structural component of pericellular matrices in which construction might be facilitated by exogenous protein. Therefore, we prefer a model in which decorin promotes close cell-cell communication in hematopoietic niches.

The Wnt3a-induced block in human B lymphopoiesis shown here is consistent with our experience with murine cells and with the results of a previous study by Rian et al,20,24 who found that proliferation of CD34+CD19+ proB was inhibited, as we show here for a broader category of CD34+CD38+ progenitors. Similarly, abnormal numbers of stem cells in mice expressing the Wnt antagonist Dkk-1 were in cycle,6 and it was reported recently that Wif1 overexpression induced a similar phenotype.45 However, it is important to stress that hematopoietic cells were in contact with stromal cells in all of these experiments, leaving open the possibility that the hematopoietic environment was altered.

Stromal cells have been identified as potential Wnt targets in several other studies. For example, Yamane et al found that B lymphopoiesis was inhibited in cocultures by the addition of Wnt-containing medium, but no response was observed in stromal cell–free cultures.14 The same effects were seen when Wnt signaling was stimulated in stromal cells by transduction of stabilized β-catenin. Kim et al used a similar design to show that stem/progenitor proliferation was reduced when they were cultured with the altered stromal cells.15 The manipulation also provided a more favorable environment for support of transplantable stem cells. Also consistent with our results, close contact between stromal cells and hematopoietic cells was required. Wnt pathway signaling confined to hematopoietic cells quickly exhausted their potential, a result seen previously with transgenic models.12,13

Nemeth et al devised another strategy for determining roles for canonical Wnt signaling in the BM microenvironment.16 Conditional targeting of β-catenin in stromal cells reduced their supporting ability for primitive hematopoietic progenitors, but not transplantable stem cells, whereas the production of osteoblasts was reduced. The latter phenomenon is consistent with our microarray findings, but it is curious that VCAM-1 expression was reduced in their β-catenin–deficient mice. As we show here for human stromal cells, and previously in mice, canonical Wnt pathway signaling reduces rather than drives VCAM-1 expression.21 The basis for this discrepancy is unknown, but might relate to the fact that β-catenin would be required to form adherens junctions in BM, where there are dose-dependent aspects of Wnt signaling.46

All of these findings suggest that MSCs are regulated by canonical Wnt pathway signaling. However, they do not exclude the possibility of direct Wnt effects on hematopoietic cells. For example, lymphoid or myeloid progenitors transduced with stable β-catenin became lineage unstable.11 Stem and progenitor cells express many combinations of Wnt receptors.1,2 and responses of purified stem/progenitor cells to recombinant Wnt proteins have been reported previously.7-9,26 Moreover, HSCs and T-lineage lymphocytes require exacting doses of canonical Wnt signaling.47

Human lymphoid progenitors are not sufficiently well described, and it is possible that Wnt3a exposure in our cocultures expanded rare, preexisting cells with erythroid potential. This would represent selection rather than true reprogramming. However, it would have to be a relatively rapid event, and our experiments with highly purified murine cells indicate that RAG-1–expressing progenitors can be directed to a distinctly different pathway.

These and other recent observations show that hematopoietic-supporting elements of BM are dynamic and responsive to multiple conditions. The OP9 cell line constitutively expresses genes associated with MSCs, but shifts to an immature osteoblastic phenotype in response to Wnt3a. It is noteworthy that a Wnt ligand is not necessary to trigger canonical signaling, because this occurs in response to hypoxia.48 This plasticity of MSCs reflects, and may account for, changes in the hematopoietic cells they support. An analogy can be found in studies of germ cells in Drosophila gonads, in which progenitors can assume stem-like characteristics when placed in the appropriate niches.49 Studies with a hematopoietic cell line suggest there may be a degree of oscillation between states, and the expression of important genes fluctuates in normal stem cells.50 Our findings indicate that some reversibility of differentiation is possible, and even human lymphoid progenitors might be reprogrammed by exposure to Wnt3a.1,20

Leukemias may originate from normal HSCs or from progenitors that acquire stem cell characteristics.51 If HSCs are the source, then Wnt signaling likely sustains early neoplastic changes.52 Wnts could also contribute to the reprogramming of committed progenitors. In that context, there is experimental evidence to suggest that components of supporting niches could be Wnt targets.53 It will be interesting to learn whether the evolution of leukemia involves changes in matrix molecules such as decorin. Such observations could have implications for regenerative medicine and for understanding how Wnt signals influence leukemic cells.46

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Karla Garrett for technical assistance, Shelli Wasson for editorial assistance, Jacob Bass and Dr Diana Hamilton for cell sorting, and Beverly Hurt for graphics assistance.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant AI020069 to P.W.K. and grant CA39481 to R.V.I.). P.W.K. holds the William H. and Rita Bell Endowed Chair in Biomedical Research (OMRF) and Scientific Director, Oklahoma Center for Adult Stem Cell Research.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: M.I. designed and performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; M.B.F. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; R.V.I. designed and performed the research and wrote the manuscript; and P.W.K. designed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Paul W. Kincade, Immunobiology and Cancer Program, 825 NE 13th St, Oklahoma City, OK 73104; e-mail: kincade@omrf.org.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal