Abstract

The niche microenvironment controls stem cell number, fate, and behavior. The bone marrow, intestine, and skin are organs with highly regenerative potential, and all produce a large number of mature cells daily. Here, focusing on adult stem cells in these organs, we compare the structures and cellular components of their niches and the factors they produce. We then define the niche as a functional unit for stem cell regulation. For example, the niche possibly maintains quiescence and regulates fate in stem cells. Moreover, we discuss our hypothesis that many stem cell types are regulated by both specialized and nonspecialized niches, although hematopoietic stem cells, as an exception, are regulated by a nonspecialized niche only. The specialized niche is composed of 1 or a few types of cells lying on the basement membrane in the epithelium. The nonspecialized niche is composed of various types of cells widely distributed in mesenchymal tissues. We propose that the specialized niche plays a role in local regulation of stem cells, whereas the nonspecialized niche plays a role in relatively broad regional or systemic regulation. Further work will verify this dual-niche model to understand mechanisms underlying stem cell regulation.

Introduction

Stem cells are defined by self-renewal and differentiation potential. Tissue-specific stem cells play an essential role in tissue generation, maintenance, and repair. A large number of blood cells, epithelial cells, and epidermal cells are produced daily over a person's lifetime. To understand how stem cells that give rise to these tissues are regulated extrinsically and intrinsically is a fundamental issue in biology and also highly relevant to regenerative medicine.

Stem cells reside in a microenvironment known as the niche. Schofield, who was the first to put forth the concept of stem cell niche, proposed that the niche: (1) provides an anatomic space to regulate stem cell number, (2) instructs a stem cell to either self-renew in close proximity or commit to differentiation at a distance, and (3) influences stem cell motility.1 Lajtha first proposed that most stem cells are not cycling, that is, are in G0 phase.2 To be able to return to a quiescent state from cycling is perhaps one of the most important properties of a stem cell because progenitor cells cannot do so.

The importance of the niche has not been fully appreciated in part because stochastic, rather than instructive, models of stem cell behavior have been preferred.3 The stochastic model predicts that stem cell fate is determined randomly. Thus far, it has been difficult to show that the likelihood of self-renewal is influenced by external factors. To understand niche function may require application of an instructive model.

Analysis of germline stem cells in the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster suggests that niche factors govern asymmetric division.4 In the ovary, 2 or 3 germline stem cells reside in a niche composed of cap cells and other cells. When a germline stem cell gives rise to 2 daughter cells, one remains a stem cell in the niche on receipt of a decapentaplegic (Dpp, a homolog of human bone morphogenetic proteins 2 and 4) signal. The other moves out of the niche and begins the differentiation program.4 This asymmetric division would have been exactly what Schofield would have predicted. This early work in Drosophila led to an interest in the niche regulation of adult stem cells in mammals.

Here we summarize progress in understanding of the stem cell niche since publication of an excellent review by Moore and Lemischka.5 Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are the best studied, as transplantation assays were established for this cell type early on and their purification techniques have progressed significantly.6,7 The niche concept also emerged from studies of HSCs. Intestinal stem cells (ISCs) provide a simpler stem cell system that produces epithelial cells continuously.8 In that system, not only do stem cells and niche cells lie next each other, but stem cells may create their own niche.9 Hair follicular stem cells (HFSCs) have been successfully marked with β-gal or fluorescent proteins, enabling in vivo tracing studies. Clonal assays are crucial to analyze stem cell differentiation potential, and it is now possible to study single HSCs, ISCs, and HFSCs.10-14 We focus on the niche of these 3 types of adult stem cells because they share certain properties. We examine stem cell heterogeneity, niche components, and extrinsic niche signals regulating stem cells, and we discuss the niche as a functional unit. Lastly, we introduce the concept that specialized and nonspecialized niches regulate stem cell activity.

The HSC niche

Functional heterogeneity of HSCs has been suggested,15 particularly with regard to self-renewal potential. CD34−, Kit+, Sca-1+, and lineage marker− bone marrow cells are highly enriched in mouse adult bone marrow HSCs.10 Among this population, HSCs with high self-renewal potential express CD150 at higher levels than do HSCs with limited self-renewal potential.16-18 Self-renewal potential may also be inversely proportional to the number of divisions a cell has undergone.19 Only when sensitive methods to monitor the division history of cells become available will the molecular basis for HSC self-renewal potential in HSCs be thoroughly understood.

Most HSCs presumably enter the cell cycle once a month,20-22 with the remaining so-called “dormant” HSCs entering the cycle less frequently.23 These 2 cell types may be interchangeable.24 Of note, both types are in G0 phase. Single-cell transplantation studies have revealed a rare HSC subset, latent HSCs, which show significant repopulating activity only after secondary transplantation, suggesting latent HSCs have long quiescent intervals.18 Alternatively, quiescent intervals of HSCs are influenced by different niches. In support of this concept, it has been found that bone marrow and spleen HSCs are functionally equivalent, but their quiescence times differ.25 An interpretation of these data would be that quiescent intervals are cell-extrinsically regulated in most HSCs but are cell-intrinsically determined in a particular type of HSCs.

Angiopoietin-1 and transforming growth factor (TGF) β1 maintain HSCs in G0 phase.26,27 HSCs express the receptor tyrosine kinase Tie2, and its ligand angiopoietin-1 inhibits HSC division in vitro. Angiopoietin-1 (Angpt1 or Ang1), expressed in osteoblasts and mesenchymal cells, probably supports HSC quiescence in vivo through integrins and N-cadherin.26 TGF-β1, which is produced by several different types of cells, must be activated from a latent form. Elegant studies indicate that integrin αvβ8-mediated TGF-β activation is essential to induce regulatory T-cell activation and prevent autoimmune disease.28 Moreover, structural analysis suggests that specific integrins are required to generate an active form of TGF-β1 from the latent form.29 These data indicate that cells expressing integrin β8 may play a role similar to TGF-β1 activation in bone marrow. For example, Schwann cells appear to be such integrin β8+ cells, suggesting that they participate in niche function.30

Adult HSCs, and likely their niches, are widely distributed in marrow of various bones in the body rather than in any particular anatomic site. Moreover, HSCs are not necessarily locked in the niche but instead are mobile.31 Nevertheless, investigators currently propose both endosteal and perivascular HSC niches (Figure 1). The endosteal niche is mainly composed of osteoblasts.32,33 The perivascular niche is composed of vascular endothelial cells,16 mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs),34 Cxcl12-abundant reticular (CAR) cells,35 perivascular stromal cells,36 and Schwann cells.30 Macrophages may also participate in the niche.37,38 After highly purified HSCs were transplanted into irradiated mice, homing analysis detected transplanted HSCs near the endosteum, particularly in the trabecular area.39,40 Because that area is well vascularized, it is probably the primary homing site. These data suggest that both endosteal and perivascular niches are present in the trabecular area. Whether the endosteal niche regulates HSCs differently than the perivascular niche is not clear. One attractive hypothesis, however, is that infrequently cycling HSCs reside in the endosteal niche, whereas frequency cycling HSCs reside in the perivascular niche.23,41 It will be necessary to demonstrate that HSCs migrate from the endosteal zone to the perivascular zone, or the other way around, to verify the 2-zone model for stem cell regulation.41

Stem cells in the bone marrow. HSCs are assumed to reside in endosteal and perivascular niches. Osteoblasts mainly constitute the endosteal niche. MSCs, perivascular stromal cells, CAR cells, and sympathetic neurons together with Schwann cells constitute the perivascular niche surrounding endothelial cells. Macrophages and adipocytes may lie between these niches and influence HSC/niche interaction.

Stem cells in the bone marrow. HSCs are assumed to reside in endosteal and perivascular niches. Osteoblasts mainly constitute the endosteal niche. MSCs, perivascular stromal cells, CAR cells, and sympathetic neurons together with Schwann cells constitute the perivascular niche surrounding endothelial cells. Macrophages and adipocytes may lie between these niches and influence HSC/niche interaction.

Stem cell factor (SCF; c-Kit ligand),36 thrombopoietin (Thpo or TPO),42,43 and Cxc11235 are candidate niche factors. SCF expression is detected in blood cells, osteoblasts, nestin+ mesenchymal cells, endothelial cells, and perivascular stromal cells.36 Conditional deletion of SCF in endothelial cells and perivascular stromal cells, but not in blood cells, osteoblasts, or nestin+ mesenchymal cells, results in a significant decrease in HSC number, suggesting that endothelial cells and perivascular stromal cells play a major role in HSC maintenance.36 SCF, Cxcl12, Pdgfr, and the leptin receptor are apparently similarly expressed in both perivascular stromal and CAR cells; thus, these cells probably overlap. Interestingly, pericytes may be closely related to MSCs,44 suggesting that MSCs are a heterogeneous population, a portion of which overlaps with perivascular stromal and CAR cells.

The ISC niche

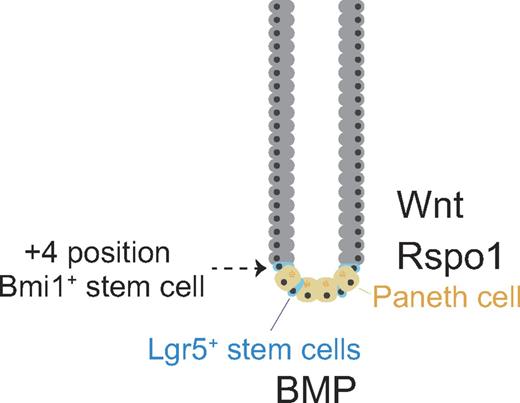

The ISC niche is less complex (than the HSC niche): the epithelial monolayer is composed of 1 type of absorptive cell (enterocyte) and 4 types of secretory cells (Goblet, Paneth, enteroendocrine, and Tuft cells).45 The mucosal surface forms crypts, which project downward, and villi, which project upward. Stem cells have been identified in the crypt of the small intestine, which consists of the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. Two types of ISCs, leucine-rich G protein-coupled receptor 5 (Lgr5)+ stem cells and Bmi1+ stem cells, have been characterized (Figure 2). Lgr5+ stem cells (also called columnar basal cells) reside at the crypt base (≥ 10 cells per crypt) and continuously cycle.46,47 Paneth cells, which are distributed between stem cells at the base of the crypt, secrete lysozyme and antimicrobial peptides, such as defensins, to protect epithelial cells from infection and are now considered to be niche cells.9 Lgr5+ stem cells give rise to both themselves and Paneth cells, which in turn regulate stem cells.9 It is suggested that infrequently cycling stem cells are located around the +4 position in the crypt (the fourth cell above the base),8 although positions can range from +2 to +7. These stem cells express the polycomb group protein Bmi1.48 Whether Bmi1+ stem cells express Lgr5 or Lgr5+ stem cells express Bmi1 is not yet clear.

Stem cells in the small intestine. Representative architecture of a crypt in the small intestine. Quiescent stem cells, or label-retaining cells (infrequently cycling stem cells can be labeled with 3H thymidine or BrdU for a long time), reside immediately above the uppermost Paneth cell at the fourth position and express Bmi1. Cycling stem cells, or columnar basal cells, lie between Paneth cells at the bottom of a crypt and express Lgr5.

Stem cells in the small intestine. Representative architecture of a crypt in the small intestine. Quiescent stem cells, or label-retaining cells (infrequently cycling stem cells can be labeled with 3H thymidine or BrdU for a long time), reside immediately above the uppermost Paneth cell at the fourth position and express Bmi1. Cycling stem cells, or columnar basal cells, lie between Paneth cells at the bottom of a crypt and express Lgr5.

The diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR) is expressed in human but not mouse cells.49 The DTR gene has been knocked into the mouse Lgr5 locus to kill Lgr5+ stem cells conditionally with diphtheria toxin.50 After Lgr5+ stem cells but not Bmi1+ stem cells were eliminated, the crypt was maintained. Furthermore, lineage tracing shows that Bmi1+ stem cells give rise to Lgr5+ stem cells, suggesting a hierarchical organization among these 2 stem cell populations.

R-spondin1 (Rspo1), which activates the canonical Wnt pathway, reportedly induces epithelial hyperplasia in the intestine after injection into normal mice.51 It was found that Rspo1 along with Noggin and epidermal growth factor can form crypt-villus structures from single Lgr5+ stem cells in culture (organoid culture).12 The Lgr family (Lgr 4-6) proteins are 7-transmembrane receptors, as are Frizzled proteins. Frizzled forms a heterodimer receptor for Wnt, with LDL receptor-related protein (Lrp) 5/6. Lgr had long been an orphan receptor, but Lgr appears to form a heterodimer receptor for Rspo, with the Lrp 5/6.52-54 Interestingly, Wnt3a and Rspo1 act synergistically to activate β-catenin.52-54 If these ligands share a common signal transducer, it is not yet clear how this synergy can be explained, although it is also possible that different signaling pathways are activated by Wnt3a and Rspo1.

Paneth cells reportedly express Wnt3, Wnt11, Rspo1, epidermal growth factor, TGF-α, and Dll4,9,55 and these factors probably regulate Lgr5+ stem cell cycling. Nonetheless, how Bmi1+ and Lgr5+ stem cells are differently regulated under similar circumstances remains unknown. Paneth cells also require further study to define their niche function and identify their niche factors.

The HFSC niche

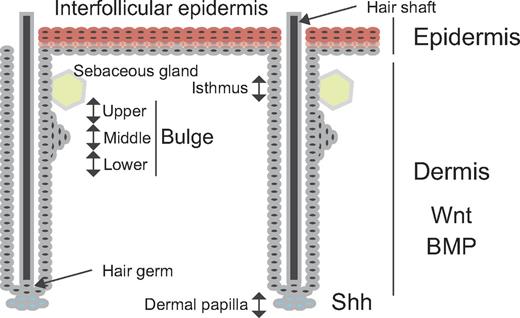

The skin is composed of the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis (subcutaneous fatty layer). The epidermis is of ectodermal origin, whereas the dermis and hypodermis are mesoderm-derived. The epidermis is composed of a multilayered epithelium. Skin cells exhibiting hairs have an appendage called the pilosebaceous unit, consisting of the hair shaft, hair follicle, sebaceous gland, and erector pili muscle (Figure 3). The basement membrane separates the epidermis from the dermis. Skin stem cells are located in 2 distinct regions: interfollicular epidermal stem cells (IFESCs) are found in the basal layer of the epidermis and HFSCs reside at the bottom of the noncycling portion in the outer root sheath, in a region called the bulge.

Stem cells in the skin. Stem cells in the basal layer of the interfollicular epidermis replenish the multilayered epithelium (spinous, granular, clear, and cornified layers). The hair follicle composes the cycling (epithelial hair germ cell) and noncycling (bulge, isthmus, infundibulum, and sebaceous gland) portion. The bulge is separated into upper, middle, and lower portions. Hair follicle stem cells in the bulge replenish hair, but also the sebaceous gland and interfollicular epidermis in response to injury.

Stem cells in the skin. Stem cells in the basal layer of the interfollicular epidermis replenish the multilayered epithelium (spinous, granular, clear, and cornified layers). The hair follicle composes the cycling (epithelial hair germ cell) and noncycling (bulge, isthmus, infundibulum, and sebaceous gland) portion. The bulge is separated into upper, middle, and lower portions. Hair follicle stem cells in the bulge replenish hair, but also the sebaceous gland and interfollicular epidermis in response to injury.

IFESCs play a major role in adult epidermal homeostasis. When they exit the cell cycle and commit to differentiation, they give rise to keratinocytes. Despite their essential role, IFESCs have not yet been isolated. Whether all or just a portion of cells in the basal layer constitute the stem cell pool is unclear. Studies of the skin, particularly in the mouse tail, suggest that a single population of proliferating progenitors is sufficient for homeostasis of epidermis.56 This finding challenges the fundamental concept of stem cells because highly proliferative tissue, such as the epidermis, can be maintained without stem cells. Nevertheless, little is yet known about the IFESC niche.

Under physiologic conditions, HFSCs mainly regenerate the hair follicle, which cycles through anagen (growth), catagen (apoptosis), and telogen (quiescence) phases. Keratin (Krt or K) promoter-driven reporters were first used to mark bulge stem cells.57,58 The K5 promoter-driven tetracycline-off system was used for conditional labeling of K5-expressing cells with histone H2B-GFP fusion protein in the bulge.57 The K15 promoter-derived fusion protein consisting of Cre recombinase, and a truncated progesterone receptor was also used for conditional labeling of K15-expressing cells in the bulge.58 These K15-Cre mice were crossed with Cre-responsive R26R reporter mice.58 In this system, Cre is translocated to the nucleus only in the presence of the progesterone agonist. Infrequently cycling cells were detected and isolated using these markers and characterized, suggesting the presence of K5+ stem cells and K15+ stem cells in the bulge. Since then, various promoters have been used to mark HFSCs.59 Lgr5+ stem cells have also been found near the bulge60 and can give rise to follicle cells, sebaceous cells, and interfollicular epidermis but mainly contribute to the hair follicle under physiologic circumstances. Sox9 and Gli1 seem to be also expressed in these stem cells.61,62

The upper portion of the bulge apparently contains stem cells different from those in the middle and lower portions (Figure 3). Lgr6+ cells found in the upper portion mainly give rise to sebaceous gland cells and interfollicular epidermis.63 In addition, Lring1+ cells and Mts24+ cells are found in the isthmus, the junction between the epidermis and the hair follicle (Figure 3).64,65 These stem cells mainly give rise to interfollicular epidermis. Blimp1+ cells found in sebaceous glands only give rise to sebaceous gland cells.66 These cells may be progenitors rather than sebaceous gland-restricted stem cells. Various overlapping populations of stem cells or progenitors are seen in, near, and moving around the bulge.67 It is not known whether there is a hierarchical order in these populations and whether specific niches control different stem cells.

Growth of the hair germ (Figure 3) is stimulated by sonic hedgehog signaling from the dermal papilla,68 which behaves like a niche for these cells. HFSCs are in close contract with the dermal papilla at the telogen. Thus, the dermal papilla can also temporarily act as a stem cell niche. IFESCs and HFSCs are also regulated by signaling from the dermis.69 Periodic Wnt/β-catenin signaling positively regulates the hair follicle cycle, and periodic secretion of bone morphogenetic proteins (Bmp2 and Bmp4) negatively regulates the hair follicle cycle.69 Bmp2 is produced by adipocytes, and Bmp4 is produced by dermal papilla, dermal fibroblasts, and interfollicular epithelium. Although the bulge has been implicated as the HFSC niche, little is known of its cellular components and factors.

The niche as a functional unit

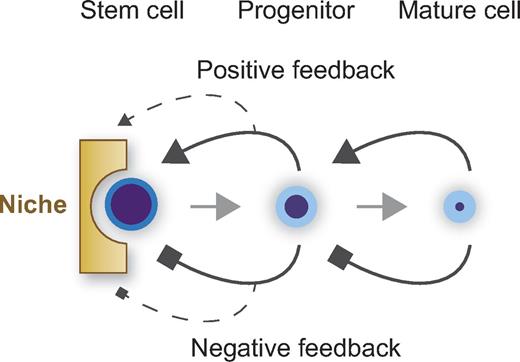

Currently, proposed niche functions include regulation of stem cell number, cell cycle, fate determination, and motility. For example, stem cell number is thought to be maintained constant by the niche under physiologic conditions. To date, however, we have no evidence that the physical space in the mammalian niche determines the number of stem cells as originally proposed by Schofield.1 We rather think that stem cell number is regulated in a more complex manner (Figure 4). The niche probably provides positive and negative factors controlling proliferation. In addition, positive and negative feedback from progenitors probably maintains stem cell supply and demand, as are autocrine and paracrine mechanisms. Feedback signaling may also be mediated by the niche. The probability that a stem cell makes a decision to self-renew should be taken to account as well. These regulations have long been postulated, but so far no study has successfully shown the existence of such a regulatory system. Perhaps we are only able to address this issue by using mathematical modeling and computational analysis.

Stem cell number and niche. Stem cell number is regulated by a niche composed of cells, extracellular matrix, and soluble factors, and also by positive and negative feedback loops from progenitors. Autocrine and paracrine loops may also regulate stem cell number.

Stem cell number and niche. Stem cell number is regulated by a niche composed of cells, extracellular matrix, and soluble factors, and also by positive and negative feedback loops from progenitors. Autocrine and paracrine loops may also regulate stem cell number.

The maintenance of stem cell quiescence is a common niche feature. Both cycling and noncycling stem cells have been found in the small intestine and skin.46,48,56 Stem cells are distinguished from progenitors in the hematopoietic system, providing the principle for hierarchical organization. Once again, most HSCs are in G0 phase, whereas most hematopoietic progenitors are cycling. Although it is yet to be demonstrated, some cycling stem cells in the intestine and skin may act as progenitors.

Among the TGF-β superfamily, BMP2 and BMP4 negatively regulate the cell cycle in HFSCs and ISCs,69,70 and TGF-β1 negatively regulates the cell cycle in HSCs.27,30 Smad1, Smad5, and Smad8 mediate BMP signaling, and Smad 1 and Smad5, but not Smad8, are expressed in HSCs. Conditional Smad1 and Smad5 double knockout mice exhibit normal HSC function but show intestinal abnormalities.71 TGF-β, but not BMPs, are negative regulators for HSCs. Quiescence of ISCs, HFSCs, and HSCs may be similarly regulated by TGF-β superfamily members.

Wnt and Notch signaling plays crucial roles in cell fate determination in embryonic development and is therefore a candidate niche factor. In the absence of Wnt protein, β-catenin is sequestered in the cytoplasm by a large complex consisting of adenomatous polyposis coli, axin, casein kinase 1α, and glycogen synthase kinase 3β. β-catenin in that complex is phosphorylated, ubiquitinylated, and degraded. In the presence of Wnt signals, axin is recruited to the Frizzled/Lrp5/6 receptor, and β-catenin is free to move into the nucleus to interact with a member of the Tcf/Lef family to activate transcription of target genes.72

Activating point mutations of β-catenin are seen in colorectal cancer,73 and in pilometrixoma, a benign skin tumor.74 They are not, however, seen in leukemia.75 Analyses of conditional β-catenin knockout mice show that β-catenin is essential to maintain ISCs76 and HFSCs.77 The role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in regulating HSCs, however, remains controversial.78-82

Notch receptors (Notch1-4) and their ligands (Delta1, Delta3, and Delta4, and Jag1 and Jag2) exist as transmembrane proteins. So-called canonical Notch signal pathway is summarized as follows: ligand binding stimulates 2 sequential proteolytic cleavages of Notch receptor, mediated by a TNF-α–converting enzyme and a presenilin-dependent γ-secretase.83 The Notch intracellular domain (NICD) then translocates to the nucleus where it interacts with a complex consisting of recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin κ J region (Rbpj-κ) and longevity-assurance gene-1. Basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors in the Hes and Hey families are up-regulated by signaling.83

NICD transgenic mice, in which NICD was expressed in all intestinal epithelium using the villin promoter, showed hyperplasia of the intestinal epithelium with a complete loss of goblet cells.84 In contrast, conditional Rbpj-κ knockout mice, constructed using P450-Cre, exhibit increased numbers of goblet cells in the intestinal epithelium and decreased enterocytes.85 These data indicate that Notch signaling is required for ISCs to commit to an enterocyte rather than a goblet cell lineage. Interestingly, treatment of adenomatous polyposis coli mutation-induced adenoma cells with a γ-secretase inhibitor converted them to goblet cells, suggesting cross-talk between Notch and Wnt signaling pathways.85

NICD transgenic mice in which NICD was expressed in the skin using the involucrin promoter showed enhanced differentiation of epidermal keratinocytes.86 In contrast, conditional Rbpj-κ knockout mice harboring K14-Cre showed thinner epidermis,87 suggesting that Notch signaling promotes IFESC differentiation into keratinocytes. Notch-dependent asymmetric division is suggested to be required for IFESC differentiation.88 It has also been reported that Notch signaling acts downstream of Wnt signaling to determine epidermal cell fate.89

Notch1 is activated under control of the T cell receptor-β locus in human T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia via the t(7;9) chromosomal translocation.83 Notch1 is essential for generation of HSCs in the aorta-gonad-mesonephros region90 and for T-cell commitment in the thymus.91 T-cell leukemia can be induced in mice transplanted with NICD-transduced bone marrow cells.92 Conditional Notch1/2 double knockout mice harboring Mx1-Cre develop chronic myelomonocytic leukemia.93 These data indicate that Notch signaling can either positively or negatively regulate commitment or proliferation, depending on blood lineage. In this regard, Notch signaling may be more important at the progenitor level than at the stem cell level.

HSCs enter the circulation at a low but constant rate.31 Intramarrow and intermarrow mobilization of HSCs may occur in physiologic conditions. This issue has not been directly addressed because, unlike HFSCs and ISCs, HSCs have not been specifically marked using fluorescent reporters. HFSCs appear to move back and forth between the bulge and the hair germ regions,67 and ISCs may similarly move around the crypt base. The question remains: do HFSCs move into different follicles and do ISCs move into different crypts? Single stem cell–derived progeny apparently occupy 1 crypt, but probably not 2 or more.94 Classically, the niche is physically close to or in direct contact with stem cells so that membrane-bound proteins can serve as niche signals; soluble factors can also regulate stem cells, and extracellular matrix provides structural support and functions in adhesion and provides a spatial context for signaling.95 If HFSCs and ISCs are regulated only by neighboring niches, are the large numbers of stem cells distributed in the body regulated totally independently? One possibility is that there could be another type of niche covering wider areas: for instance, the dermis for HFSCs and IFESCs or the lamina propria for ISCs.

Specialized and nonspecialized niches

We propose 2 types of niches, based on the anatomic structure, and hypothesize that each plays a distinct role in stem cell regulation. One can be viewed as a specialized niche, whereas the other is nonspecialized (Figure 5). Most stem cells are presumably under the dual regulation of both niche types. The specialized niche, composed of 1 or a few cell types, resides next to stem cells to support them directly (local regulation). Both stem cells and specialized niche cells together rest on a basement membrane of specialized extracellular matrix consisting of laminins, collagen IV, perlecan, and nodogens.96 The basement membrane is considered a portion of the specialized niche that directly regulates the cell cycle and stem cell polarity. The specialized niche could also be termed the epithelial niche because specialized niche cells are often present in the epithelium.

Basement membrane and niches. Specialized and nonspecialized niches are anatomically distinct in relation to the basement membrane (bm). The specialized niche in close proximity to stem cells arrays on the basement membrane in the epithelium. In concept, the specialized niche is composed of particular cell types directly regulating survival and proliferation of stem cells. The nonspecialized niche, composed of numerous cell types widely distributed among connective tissues, directly or indirectly regulates stem cells in a region. (A) ISCs and specialized niche cells, Paneth cells, form a monolayer of the epithelium on the basement membrane. The lamina propria under the basement membrane may function as the nonspecialized niche. (B) IFESCs and specialized niche cells in the basal layer lie on the basement membrane of the epidermis. The dermis may function as a nonspecialized niche. (C) Spermatogonia, lying on the basement membrane, give rise to spermatocytes and spermatids in the seminiferous epithelium of the testis. Sertoli cells most likely serve as specialized niche cells. Leydig cells, myoid cells, and vascular endothelial cells under the basement membrane may serve as a nonspecialized niche. (D) In the bone marrow, the basement membrane is found underneath the vascular endothelium. HSCs do not lie on the basement membrane with endothelial cells. HSCs lie among the nonspecialized niche.

Basement membrane and niches. Specialized and nonspecialized niches are anatomically distinct in relation to the basement membrane (bm). The specialized niche in close proximity to stem cells arrays on the basement membrane in the epithelium. In concept, the specialized niche is composed of particular cell types directly regulating survival and proliferation of stem cells. The nonspecialized niche, composed of numerous cell types widely distributed among connective tissues, directly or indirectly regulates stem cells in a region. (A) ISCs and specialized niche cells, Paneth cells, form a monolayer of the epithelium on the basement membrane. The lamina propria under the basement membrane may function as the nonspecialized niche. (B) IFESCs and specialized niche cells in the basal layer lie on the basement membrane of the epidermis. The dermis may function as a nonspecialized niche. (C) Spermatogonia, lying on the basement membrane, give rise to spermatocytes and spermatids in the seminiferous epithelium of the testis. Sertoli cells most likely serve as specialized niche cells. Leydig cells, myoid cells, and vascular endothelial cells under the basement membrane may serve as a nonspecialized niche. (D) In the bone marrow, the basement membrane is found underneath the vascular endothelium. HSCs do not lie on the basement membrane with endothelial cells. HSCs lie among the nonspecialized niche.

The nonspecialized niche is composed of mesenchymal cells, such as MSCs, fibrocytes, fibroblasts, adipocytes, vascular endothelial cells, neurons, and blood cells. Signals from the nonspecialized niche are probably not as simple as those from the specialized niche because they are multiple and impact stem cells directly and indirectly. The nonspecialized niche may also affect stem cells via a specialized niche or be responsible for spatial organization or regional synchronization of stem cells. If stem cells are damaged in a particular region, the remaining stem cells could be recruited to that region to rescue them. In this sense, the nonspecialized niche plays a role in relatively broad regional or systemic regulation of stem cells. The nonspecialized niche can alternatively be considered a mesenchymal niche because of its localization.

Figure 5 illustrates the concept of specialized and nonspecialized niches among representative stem cells. Both ISCs and Paneth cells form in a 2-dimensional plane on the basement membrane (Figure 5A) to create a specialized niche that directly regulates ISC proliferation. The lamina propria, found in villi and between crypts, contains actin filaments, blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, peripheral nerves, macrophages, and lymphocytes. It is interesting to know whether the lamina propria, as part of the nonspecialized niche, has an effect on ISCs. If this is the case, there is supposedly a regional or systemic regulation of ISC number per crypt.

In the skin, the specialized niche is less well understood than the nonspecialized niche. Niche cells are presumably present in the bulge and basal layer on the basement membrane (Figure 5B top). The dermis is the connective tissue containing fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and nerve cells. Epidermal-dermal interactions are considered important in development of the hair follicle, support of the hair cycle, and epidermal wound repair. However, the role of the dermis as a nonspecialized niche requires further study.

The seminiferous epithelium in the testis has the unique 3-dimensional structure consisting of spermatogenic cells and Sertoli cells (Figure 5C). Spermatogonial stem cells rest on the basement membrane between Sertoli cells. Like Paneth cells, Sertoli cells exhibit a large number of lysosomes. Sertoli cells function as the specialized niche by secreting glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor, which induces self-renewal of spermatogonia.97 The interstitium located between seminiferous tubes probably acts as the nonspecialized niche. Myoid cells lie beneath the basement membrane, and Leydig cells, fibrocytes, vascular endothelial cells, macrophages, and neurons are present in the interstitium. All these cells could be members of the nonspecialized niche, supporting the previous proposal.98

There is no specialized niche for HSCs. Instead, heterogeneous connective tissue or stromal cells function as a nonspecialized niche (Figure 1). This conversely permits HSC mobilization in the bone marrow. The basement membrane is located underneath the vascular endothelium monolayer in bone marrow. The nonspecialized niche where HSCs reside can be regarded as lying under the basement membrane, similar to the nonspecialized niche in other tissues (Figure 5D). The unusual anatomic sites of HSCs in the nonspecialized niche, but not in the specialized niche, suggest that HSCs may be regulated in a manner that is fundamentally different from that of other stem cells. If so, it may not be so crucial to specify niche cells and their anatomic sites for HSCs as it is for other stem cells to understand niche function at the molecular level.

In E10.5 mouse embryos, HSCs emerge from subaortic patches underneath the basement membrane of the dorsal aorta.99 A positional relationship between HSCs and a nonspecialized niche may be maintained from embryonic to adult stages, although the functional role of nonspecialized niche may differ between the aorta-gonad-mesonephros region and adult bone marrow. It is noteworthy that, in the yolk sac, hemangioblasts, the common progenitors of blood cells and vascular endothelial cells, probably arise from the mesodermal monolayer above the basement membrane. In this regard, the developmental niche in the yolk sac differs structurally and functionally from that of the adult bone marrow.

In conclusion, a variety of niche components act together to regulate stem cells in a complex but concerted manner. Whether stem cells are regulated in an instructive fashion is an important issue in stem cell biology, particularly when we intend to manipulate stem cells. Action of specialized niche factors is possibly more instructive than is that of nonspecialized niche factors. On the other hand, the regulation by nonspecialized niche may be broader and systemic than that by the specialized niche. The niche supposedly maintains a quiescent state, determines cell fate, and controls stem cell mobility. To determine how specialized and nonspecialized niches contribute to these functions, we must define molecular mechanisms underlying stem cell regulation in both steady and dynamic states, such as developmental or regenerative processes. Once we know how the stem cells are regulated in physiologic conditions or dysregulated in pathologic conditions, new therapeutic strategies targeting stem cells can be designed that could be useful for stem cell-targeted cancer therapy or regenerative medicine.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Fumio Arai for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A and C) and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas in Japan.

Authorship

Contribution: H.E. and T.S. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Hideo Ema, Department of Cell Differentiation, Sakaguchi Laboratory of Developmental Biology, Keio University School of Medicine, 35 Shinano-machi, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-8582, Japan; e-mail: hema@a7.keio.jp.