Abstract

Immunomodulators are effective in controlling hematologic malignancy by initiating or reactivating host antitumor immunity to otherwise poorly immunogenic and immune suppressive cancers. We aimed to boost antitumor immunity in B-cell lymphoma by developing a tumor cell vaccine incorporating α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer) that targets the immune adjuvant properties of NKT cells. In the Eμ-myc transgenic mouse model, single therapeutic vaccination of irradiated, α-GalCer–loaded autologous tumor cells was sufficient to significantly inhibit growth of established tumors and prolong survival. Vaccine-induced antilymphoma immunity required NKT cells, NK cells, and CD8 T cells, and early IL-12–dependent production of IFN-γ. CD4 T cells, gamma/delta T cells, and IL-18 were not critical. Vaccine treatment induced a large systemic spike of IFN-γ and transient peripheral expansion of both NKT cells and NK cells, the major sources of IFN-γ. Furthermore, this vaccine approach was assessed in several other hematopoietic tumor models and was also therapeutically effective against AML-ETO9a acute myeloid leukemia. Replacing α-GalCer with β-mannosylceramide resulted in prolonged protection against Eμ-myc lymphoma. Overall, our results demonstrate a potent immune adjuvant effect of NKT cell ligands in therapeutic anticancer vaccination against oncogene-driven lymphomas, and this work supports clinical investigation of NKT cell–based immunotherapy in patients with hematologic malignancies.

Introduction

Hematologic malignancies typically express the necessary machinery for eliciting antitumor immunity, such as costimulatory molecules, yet many tumors are poorly immunogenic. Therapeutic vaccination strategies that incorporate immune adjuvants are likely to enhance immune recognition and targeting of hematologic cancers, an example being in mice vaccinated against mouse lymphomas with whole tumor cells loaded with CpG adjuvant.1

Natural killer T (NKT) lymphocytes represent an immune regulatory population with recognized capacity for inducing innate (eg, NK cells) and adaptive (eg, CD8 T cell) antitumor immunity,2-4 by their unique ability to rapidly produce large quantities of cytokines on TCR ligation, in particular IFN-γ.5,6 As a result, the synthetic CD1d-dependent NKT cell ligand α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer) has been used for its NKT cell–mediated immune adjuvant properties in anticancer therapies.7-10 Initial attempts to stimulate NKT cells in situ were to simply infuse soluble α-GalCer, which briefly inhibited the tumor growth, but had limited effects on survival.11,12 In addition, multiple injections of α-GalCer led to deleterious effects including long-term NKT cell functional anergy or unresponsiveness.12 Subsequently, α-GalCer was loaded onto dendritic cells (DCs) as a vaccine. This approach induced more potent antitumor effects than soluble α-GalCer injections, mainly by prolonging NKT cell IFN-γ production and preventing induction of NKT cell anergy, and was able to significantly improve the activity of the DC vaccine if coadministered with tumor antigens.10,13,14 The cumbersome nature of inducing and expanding DC from patients' peripheral blood monocytes for autologous α-GalCer–pulsed DC therapy stimulated the use of irradiated tumor cells as a vehicle to deliver α-GalCer in vivo.15-17 Here a full complement of tumor antigens (including undefined ones) and α-GalCer are codelivered, thus allowing generation of innate immunity and potentially long-term tumor-specific T-cell adaptive immunity. In a prophylactic setting, whole tumor cells loaded with α-GalCer were able to protect mice against subsequent challenge with live tumor cells15,16 and were also shown to be partially effective at inhibiting growth of established solid tumors17 (S.R.M., K.S., M. Li, H.D., S.F. Ngiow, M.J.S., Transient Foxp3+ regulatory T cell depletion enhances therapeutic anticancer vaccination targeting the immune-stimulatory properties of NKT cells, manuscript submitted, August 2012), demonstrating the ability of this vaccine to work successfully in a therapeutic setting. Furthermore, whole tumor cells loaded with α-GalCer provided a more effective induction of protective immunity than equivalent α-GalCer–loaded DCs,16 suggesting that delivery of whole tumor cells with the appropriate adjuvant is the most efficient source of tumor antigens.

The importance of NKT cells in controlling hematologic malignancies is highlighted by growing evidence that depleted numbers of NKT cells and/or dysfunction of these cells in patients correlates with enhanced tumor development, poor treatment outcomes, and ultimately reduced survival. For example, multiple myeloma (MM) progression is associated with loss of IFN-γ–secreting NKT cells.18,19 This functional defect could be overcome using DCs pulsed with α-GalCer, suggesting that clinical progression in patients with monoclonal gammopathies is associated with an acquired but reversible defect in NKT cell function. NKT cells have also been implicated in the control of other hematologic cancers, including B-cell lymphoma and leukemia,20 largely because of high-density expression of CD1d molecules on these tumors.21,22 Thus, specifically targeting in situ activation of NKT cells in blood cancer settings may reestablish the antitumor function of these cells and downstream NK cells and CD8 T cells.

Up to 70% of all human malignancies show elevated expression of the oncogenic transcription factor MYC. In some hematologic cancers, such as Burkitt lymphoma and subsets of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, elevated MYC levels are a direct consequence of genetic aberrations involving the MYC locus.23 Chromosomal translocations that join cellular MYC (c-myc) with immunoglobulin (Ig) heavy-chain or light-chain loci are thought to be the crucial initiating oncogenic events in the development of B-cell neoplasms.23 In this study, we transplanted primary B-cell lymphomas derived from Eμ-myc transgenic mice24 into immunocompetent recipients to investigate induction of antitumor immunity against established lymphoma by delivering therapeutic vaccination with α-GalCer–loaded autologous tumors. Vaccine treatment resulted in significant inhibition of Eμ-myc lymphoma growth and was associated with IFN-γ–dependent antitumor activities of NKT cells, NK cells, and CD8 T cells.

Methods

Mice

Inbred C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) mice were purchased from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research. C57BL/6 gene-targeted knockout (KO) Jα18KO, TCRδKO, IL-12p35KO, IL-12-p40KO, and IL-18KO mice were bred and maintained at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Center. All mice were backcrossed to C57BL/6 at least 10 times. Mice were used at the ages of 6-10 weeks. All experiments were performed in accordance with the animal ethics guidelines ascribed by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and approved by the Peter MacCallum Cancer Center Animal Ethics Committee.

Hematologic tumor models

All tumor models used in this study were generated on the C57BL/6 background. Eμ-myc transgenic mice develop B-cell lymphomas because of constitutive expression of c-myc and represent human non-Hodgkin lymphoma.24 Eμ-myc clones 299 and 4242 used for transplantation were freshly isolated lymphomas from lymph nodes of Eμ-myc transgenic mice, and stably transduced GFP or luciferase lines were engineered by retroviral transduction of these cells as previously described.25 Eμ-myc cells were maintained in high-glucose modified DMEM media supplemented with 10% FCS and 20μM 2-mercaptoethanol. WT or gene-targeted mice were inoculated intravenously with 1 × 105 tumor cells, unless otherwise indicated. Tumor growth was monitored by measuring either GFP+ cell events in the peripheral blood by flow cytometry (GFP-expressing clones) or by live bioluminescent imaging using the IVIS imaging platform (Xenogen; luciferase-expressing clones). Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with the t(8;21) translocation accounts for ∼ 10% of AML cases and involves fusion of the AML1 (RUNX1) and ETO genes, to express the resulting AML1-ETO fusion protein.26 AML-ETO9a+Nras tumor cells were made by retroviral transduction of AML-ETO9a oncogene cotransduced with Nras.27 WT mice received 1 × 106 of GFP/luciferase cotransduced AML-ET09a tumor cells, and leukemia development was monitored by live bioluminescent imaging and GFP+ cell events in blood.

Reagents and flow cytometry

α-GalCer was from Alexis Biochemical. OCH, α-C-GalCer, and β-mannosylceramide (β-ManCer) were kindly provided by S. Porcelli (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, NY), R. Bittman (Queens College, New York, NY), and G. Besra (University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom). α-GalCer–loaded CD1d tetramer was kindly provided by D. Godfrey (University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia). Anti–mouse mAbs to CD3 (17A2), CD8α (53-6.7), CD1d (1B1), NK1.1 (PK136), IFN-γ (XMG1.2), TCRβ (H57-597), CD19 (1D3), B220 (RA3-6B2), CD138 (281-2), H-2Kb (28-14-8), and I-A/I-E (M5/114.15.2) and associated isotype control Igs were purchased from BD Biosciences, eBioscience, or R&D Systems. Cells were stained at predetermined optimal concentrations of mAb for 30 minutes at 4°C in PBS containing 2% FCS and 0.01% NaN3. In some instances, flow count beads (BD Biosciences) were added to the staining to allow for calculation of cell numbers on acquisition. For intracellular staining with IFN-γ, Golgiplug (BD Biosciences) was added to the cells for 2 hours to inhibit cytokine release from the Golgi/endoplasmic reticulum complex. Permeabilization and fixation of cells were conducted using the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm kit, according to the manufacturer's instructions (BD Biosciences). Stained cells were acquired on a LSR-II or Canto-II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo Version 7.6 software (TreeStar).

Vaccination and antibody-mediated depletions

Eμ-myc, AML-ETO9a, or Vk*myc tumor cells were loaded overnight with 500 ng/mL of α-GalCer or another indicated glycolipid. Tumor cell viability was not affected by glycolipid treatment. For prophylactic vaccination, live α-GalCer–loaded tumors cells, determined by trypan blue exclusion, were inoculated intravenously into mice after extensive washing to remove unbound α-GalCer. For therapeutic vaccination, α-GalCer–loaded tumors were irradiated (50 Gy) before administration to arrest proliferation of the cells. Single vaccine treatment was given on detection of established peripheral tumor load: ∼ 1% GFP+ events in blood for Eμ-myc and AML-ETO9a tumors, and 2%-5% M-spike in serum for Vk*myc. Some WT mice received 3 intraperitoneal doses of 100 μg anti–IFN-γ (H22), 100 μg anti-CD8β (53.5.8), 250 μg anti-CD4 (GK1.5), 100 μg anti-asialoGM1, or control Ig (cIg; Mac-4 or 2A3) mAb at day −1, day +1, and day +8 relative to vaccination to neutralize or deplete cell subsets and cytokines. This anti-asialoGM1 treatment protocol has previously been shown to effectively deplete NK cells while sparing NKT cells.28 Anti-asialoGM1 (anti-aGM1) was purchased from Wako Chemicals, anti-CD8β (53.5.8) was made by Bio-X-cell, and anti-CD4 (GK1.5) and anti–IFN-γ (H22) were kindly provided by R. Schreiber (Washington University, St Louis, MO).

Detection of cytokines

Cytokine levels in mouse serum were detected using cytometric bead array (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Acquisition was performed on an LSR-II or Canto-II (BD Biosciences). A total of 300 bead events for each cytokine were collected. Analysis of cytometric bead array data was performed using the FCAP array software (Soft Flow Version 2). IL-18 concentration was determined using an ELISA kit from MBL International.

In vivo bioluminescent imaging

Bioluminescent imaging was performed the IVIS platform (Xenogen). The acquisition and analysis software Living Image Version 2.5 (Xenogen) was used for all in vivo imaging and quantification of tumor bioluminescence. Mice harboring luciferase-transduced tumors were administered 100 μL of 1.5 mg/mL D-luciferin substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) by intraperitoneal injection and anesthetized with 1%-2% isoflurane. After 5 minutes, 2 or 3 mice at a time were then placed inside the light-tight camera box and imaged for 1-2 minutes. Detected bioluminescent signal in the whole mouse was quantified as total photon counts using the Living Image Version 2.5 software.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Kaplan-Meier plots were used to analyze mouse survival, and a log-rank test was performed to assess the statistical significance of differences between survival curves. For all other data for which statistics were performed, a 2-tailed t test was used for assessment of differences between groups (GraphPad Prism Version 5 software). Values of P < .05 were considered significant.

Results

Loading α-GalCer onto B-cell tumors prevents lymphoma development in immunocompetent mice

Transplantation of Eμ-myc–driven tumors into immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice resulted in rapid development of aggressive disseminated B-cell lymphomas with median survival of ∼ 20 days. To determine whether formation of Eμ-myc lymphomas could be suppressed by targeting them for NKT cell recognition, Eμ-myc 299 cells were loaded with α-GalCer before transplantation into WT C57BL/6 mice. Notably, loading the Eμ-myc cells with α-GalCer had no indirect effect on cell survival or proliferation in vitro (data not shown). Development of lymphoma was compared against mice receiving unloaded Eμ-myc cells (Figure 1). Loading Eμ-myc tumors with α-GalCer, which retain expression of CD1d, albeit at lower levels than normal B cells (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article), completely prevented tumor development with disease-free survival for at least 100 days. In addition, administration of α-GalCer–loaded tumors resulted in effective immunization, as growth of parental Eμ-myc tumor cells was suppressed in vaccinated mice rechallenged at day 28 (Figure 1B). To assess whether NKT cells were required for prevention of tumor development, type I NKT cell–deficient Jα18KO mice were challenged with α-GalCer–loaded tumors. In these mice, tumor development was comparable to Jα18KO mice receiving unloaded tumors (Figure 1A-B), suggesting that NKT cells were critical in the response. A significant expansion of NKT cells was observed in the spleens of WT mice 7 days after administration of α-GalCer–loaded Eμ-myc tumors, confirming that NKT cells specifically responded to administration of glycolipid-loaded tumors (Figure 1C).

Prophylactic vaccine inhibits Eμ-myc–driven lymphoma in immunocompetent mice. WT and Jα18KO C57BL/6 mice received 1 × 105 live, unloaded, or α-GalCer–loaded Eμ-myc 299 tumor cells intravenously. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots showing tumor burden (gated B220+GFP+ cell population) at day 14 in blood in WT and Jα18KO mice. (B) Data are mean ± SEM (n = 5); tumor burden in blood of WT and Jα18KO mice challenged with unloaded or αGalCer-loaded tumor cells. Vaccinated WT mice were rechallenged at day 28 with 1 × 105 parental Eμ-myc tumor cells, and tumor growth was compared with equivalent tumor inoculation into naive WT mice (right graph). (C) Percentage (left graph) and total cell count (right graph) of CD1d tetramer+ NKT cells in spleen of non–tumor-bearing or Eμ-myc tumor-bearing mice 7 days after inoculation. **P < .001 (unpaired t test). ***P < .0001 (unpaired t test). ns indicates not significant. Two independent experiments were performed.

Prophylactic vaccine inhibits Eμ-myc–driven lymphoma in immunocompetent mice. WT and Jα18KO C57BL/6 mice received 1 × 105 live, unloaded, or α-GalCer–loaded Eμ-myc 299 tumor cells intravenously. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots showing tumor burden (gated B220+GFP+ cell population) at day 14 in blood in WT and Jα18KO mice. (B) Data are mean ± SEM (n = 5); tumor burden in blood of WT and Jα18KO mice challenged with unloaded or αGalCer-loaded tumor cells. Vaccinated WT mice were rechallenged at day 28 with 1 × 105 parental Eμ-myc tumor cells, and tumor growth was compared with equivalent tumor inoculation into naive WT mice (right graph). (C) Percentage (left graph) and total cell count (right graph) of CD1d tetramer+ NKT cells in spleen of non–tumor-bearing or Eμ-myc tumor-bearing mice 7 days after inoculation. **P < .001 (unpaired t test). ***P < .0001 (unpaired t test). ns indicates not significant. Two independent experiments were performed.

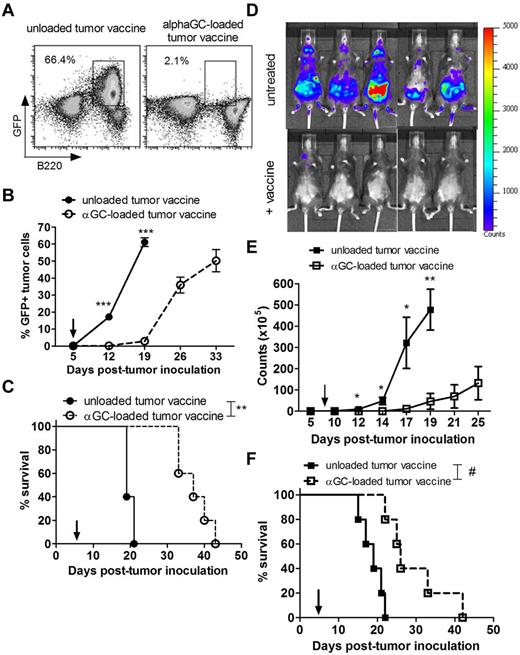

Therapeutic vaccination with irradiated, α-GalCer–loaded tumor cells suppresses growth of 2 Eμ-myc tumor clones

Two independently derived Eμ-myc lymphomas (299 and 4242) were used to assess the effectiveness of α-GalCer–loaded tumors as a therapeutic vaccine against established B-cell lymphoma in mice. After overnight pulsing with α-GalCer, Eμ-myc cells were irradiated to arrest proliferation of the cells before inoculation. Single intravenous vaccine treatment with irradiated α-GalCer–loaded Eμ-myc tumors, administered on detection of disseminated lymphoma in transplanted WT C57BL/6 mice, was sufficient to delay outgrowth of both 299 (Figure 2A-C) and 4242 (Figure 2D-F) Eμ-myc lymphoma for at least 14 days, with significant survival advantage compared with mice receiving an unloaded vaccine (median survival with 299 clone, 37 days with unloaded tumor vaccine vs 19 days with α-GalCer–loaded tumor vaccine; P = .002, log-rank test; Figure 2C). In comparison, intravenous administration of soluble α-GalCer did not suppress established Eμ-myc tumor growth (data not shown). Interestingly, vaccine-induced immunity was tumor type-specific but not lymphoma clone-specific, as vaccination with α-GalCer–loaded AML-ETO9a tumors could not suppress Eμ-myc 299 tumor growth, whereas treatment with α-GalCer–loaded Eμ-myc 4242 tumors effectively suppressed Eμ-myc 299 tumor growth (supplemental Figure 2).

Suppression of established Eμ-myc tumor growth in mice treated with α-GalCer–loaded tumor vaccine. WT mice were challenged with 1 × 105 GFP-expressing Eμ-myc 299 tumor cells (A-C) or 1 × 105 luciferase-expressing Eμ-myc 4242 tumor cells (D-F) and 5 days later treated with a single administration of irradiated, unloaded, or α-GalCer–loaded autologous Eμ-myc tumor cells. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots showing 299 tumor burden (gated B220+GFP+ cell population) at day 19 in blood. (B) Data are mean ± SEM (n = 5) 299 tumor burden in blood of WT mice after vaccine treatment. ***P < .001 (unpaired t test). (C) Overall survival of mice (n = 5) receiving unloaded or α-GalCer–loaded 299 tumor vaccine on day 5. **P = .002 (log-rank test). (D) Representative in vivo bioluminescent images of Eμ-myc 4242 tumor burden (luciferase activity) in untreated (top panels) or vaccine-treated (bottom panels) mice at 14 days after tumor inoculation. (E) Data are mean ± SEM (n = 5) bioluminescent photon counts of total 4242 tumor burden in the whole mouse quantified from live bioluminescent imaging as in panel A. **P < .005 (unpaired t test). *P < .05 (unpaired t test). (F) Overall survival of untreated or vaccine-treated mice (n = 5). #P = .004 (log-rank test). Arrows indicate day of vaccination. Three independent experiments were performed.

Suppression of established Eμ-myc tumor growth in mice treated with α-GalCer–loaded tumor vaccine. WT mice were challenged with 1 × 105 GFP-expressing Eμ-myc 299 tumor cells (A-C) or 1 × 105 luciferase-expressing Eμ-myc 4242 tumor cells (D-F) and 5 days later treated with a single administration of irradiated, unloaded, or α-GalCer–loaded autologous Eμ-myc tumor cells. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots showing 299 tumor burden (gated B220+GFP+ cell population) at day 19 in blood. (B) Data are mean ± SEM (n = 5) 299 tumor burden in blood of WT mice after vaccine treatment. ***P < .001 (unpaired t test). (C) Overall survival of mice (n = 5) receiving unloaded or α-GalCer–loaded 299 tumor vaccine on day 5. **P = .002 (log-rank test). (D) Representative in vivo bioluminescent images of Eμ-myc 4242 tumor burden (luciferase activity) in untreated (top panels) or vaccine-treated (bottom panels) mice at 14 days after tumor inoculation. (E) Data are mean ± SEM (n = 5) bioluminescent photon counts of total 4242 tumor burden in the whole mouse quantified from live bioluminescent imaging as in panel A. **P < .005 (unpaired t test). *P < .05 (unpaired t test). (F) Overall survival of untreated or vaccine-treated mice (n = 5). #P = .004 (log-rank test). Arrows indicate day of vaccination. Three independent experiments were performed.

NKT cells, NK cells, and CD8 T cells are critical for therapeutic effect of α-GalCer–loaded tumor cell vaccine

The therapeutic efficacy of α-GalCer–loaded tumors against established Eμ-myc 299 lymphoma was assessed in mice deficient or depleted of NKT cells, NK cells, CD8 T cells, CD4 T cells, and gamma/δ (γδ) T cells. Type I NKT cells were critical for vaccine efficacy in therapy evidenced by complete abrogation of therapeutic effect in Jα18KO recipients (Figure 3A). In addition, NK cell or CD8 T-cell depletion in Eμ-myc tumor-bearing WT mice before vaccine treatment also resulted in complete loss of therapeutic efficacy, despite no direct effect of NK cell or CD8 T-cell depletion on tumor growth in nonvaccinated mice (Figure 3A). Depletion of CD4 T cells decreased protection elicited by the vaccine; however, significant tumor growth inhibition was still observed. By contrast, suppression of Eμ-myc tumor growth after vaccination was not altered in TCRδKO mice, indicating that γδ T cells were not important for immune surveillance in this setting.

NKT cells, NK cells, and CD8 T cells are required for therapeutic efficacy of the vaccine. WT or genetic knockout mice were challenged with 1 × 105 Eμ-myc 299 tumor cells and treated on day 5 with irradiated, α-GalCer–loaded tumor cells, or left untreated. (A) Eμ-myc tumor burden in blood 19 days after tumor inoculation, in untreated or vaccine-treated WT, NKT cell–deficient Jα18KO, and gamma/δ T cell–deficient TCRδKO mice. As indicated, some WT mice received mAb-based depletion of NK cells (anti-aGM1), CD8 T cells (anti-CD8β), CD4 T cells (anti-CD4), or isotype control mAb (cIg). ***P < .0001 (unpaired t test). ns indicates not significant. (B) Percentages of NKT cells (left), NK cells (middle), and CD8 T cells (right) in blood at the indicated time points before and after vaccination in Eμ-myc tumor-bearing and non–tumor-bearing (naive) WT mice. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 5. ***P < .0001 (unpaired t test). **P < .003 (unpaired t test). *P < .03 (unpaired t test). (C) The percentage of NKT cells (left) and NK cells (right) in blood of untreated and treated WT and Jα18KO mice 12 days after tumor inoculation. Dotted line indicates baseline percentage from an age- and sex-matched non–tumor-bearing mouse. ***P < .001 (unpaired t test). **P < .01 (unpaired t test). *P < .05 (unpaired t test). ns indicates not significant. (A-C) Data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

NKT cells, NK cells, and CD8 T cells are required for therapeutic efficacy of the vaccine. WT or genetic knockout mice were challenged with 1 × 105 Eμ-myc 299 tumor cells and treated on day 5 with irradiated, α-GalCer–loaded tumor cells, or left untreated. (A) Eμ-myc tumor burden in blood 19 days after tumor inoculation, in untreated or vaccine-treated WT, NKT cell–deficient Jα18KO, and gamma/δ T cell–deficient TCRδKO mice. As indicated, some WT mice received mAb-based depletion of NK cells (anti-aGM1), CD8 T cells (anti-CD8β), CD4 T cells (anti-CD4), or isotype control mAb (cIg). ***P < .0001 (unpaired t test). ns indicates not significant. (B) Percentages of NKT cells (left), NK cells (middle), and CD8 T cells (right) in blood at the indicated time points before and after vaccination in Eμ-myc tumor-bearing and non–tumor-bearing (naive) WT mice. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 5. ***P < .0001 (unpaired t test). **P < .003 (unpaired t test). *P < .03 (unpaired t test). (C) The percentage of NKT cells (left) and NK cells (right) in blood of untreated and treated WT and Jα18KO mice 12 days after tumor inoculation. Dotted line indicates baseline percentage from an age- and sex-matched non–tumor-bearing mouse. ***P < .001 (unpaired t test). **P < .01 (unpaired t test). *P < .05 (unpaired t test). ns indicates not significant. (A-C) Data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

Both NKT cells and NK cells were enriched in the blood of vaccine-treated mice. This cell expansion was transient, peaking at 7 days after vaccination and returning to baseline levels by day 14 after vaccination (Figure 3B). CD8 T cell levels did not increase significantly until 14 days after vaccination. IFN-γ was required for maximal expansion of both NKT cell and NK cells in the blood, with reduced expansion observed when IFN-γ was neutralized. Furthermore, decreased NKT cell expansion after NK cell depletion and vice-versa suggests cross-talk between these populations in response to vaccination (Figure 3C).

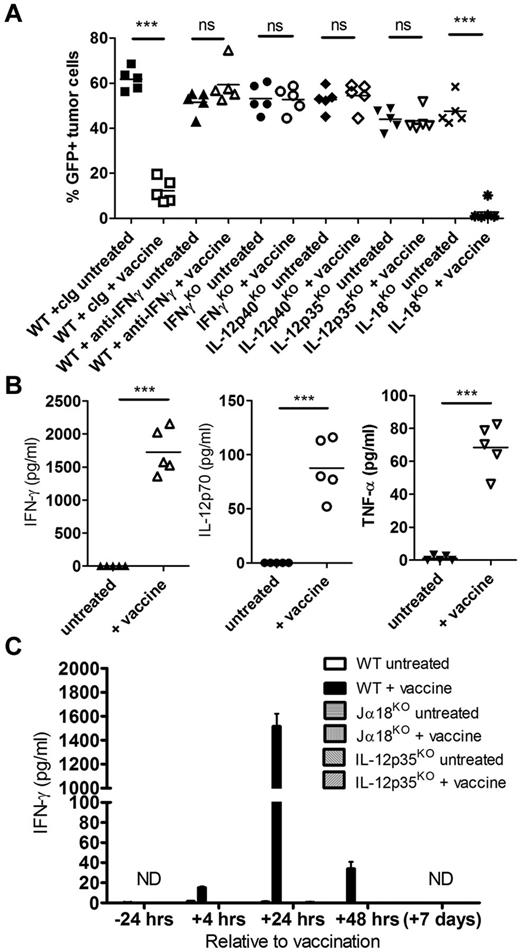

IL-12–dependent IFN-γ production in response to vaccination is critical for antilymphoma immunity

IFN-γ was important for optimal expansion of both NKT cells and NK cells in the blood of Eμ-myc tumor-bearing mice after vaccination (Figure 3C), suggesting a role for this pro-inflammatory cytokine in lymphocyte activation after vaccine treatment. The therapeutic efficacy of α-GalCer–loaded tumor vaccine was completely abrogated in the absence of IFN-γ, shown both in IFN-γKO mice and when IFN-γ was neutralized in WT mice (Figure 4A). Consistent with a role for IFN-γ in this setting, a large spike of IFN-γ was detected in the serum of treated mice 24 hours after vaccination (Figure 4B). Interestingly, IFN-γ serum levels were minimal (< 50 pg/mL) at 4 hours and 48 hours after vaccination, indicating a specific and transient production of IFN-γ (Figure 4C). In addition, IFN-γ production was entirely dependent on both NKT cells and IL-12, as IFN-γ was undetectable in vaccinated Jα18KO and IL-12p35KO mice (Figure 4C). To confirm a role for IL-12 in vaccine-induced immunity, we observed that the vaccine was ineffective in both IL-12p40KO and IL-12p35KO mice (Figure 4A), and systemic IL-12p70 levels were significantly elevated in WT mice 24 hours after vaccination (Figure 4B). For other cytokines assessed, including TNF-α, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-17, and IL-1β, only TNF-α was detectable after vaccine treatment at significantly greater levels than untreated mice (Figure 4B; and data not shown). Because IL-12 synergizes with IL-18 for optimal IFN-γ production by NK cells,29-31 the effectiveness of the vaccine as well as IFN-γ production was assessed in IL-18KO mice. No alteration in therapeutic efficacy was observed in IL-18KO mice (Figure 4A). In addition, systemic IL-18 levels were similar in untreated and vaccinated WT mice, and IFN-γ levels 24 hours after vaccination were comparable between WT and IL-18KO mice (supplemental Figure 3).

Systemic IL-12–dependent IFN-γ production after vaccination is required for lymphoma growth inhibition. WT or genetic cytokine knockout mice were challenged with 1 × 105 Eμ-myc 299 tumor cells and treated on day 5 with irradiated, α-GalCer–loaded tumor cells, or left untreated. (A) Eμ-myc tumor burden in blood 19 days after tumor inoculation, in untreated or vaccine-treated WT, IFN-γKO, IL-12KO (p35KO and p40KO), and IL-18KO mice. As indicated, some WT mice received mAb-based depletion of IFN-γ or isotype control mAb (cIg). (B) Serum cytokine levels from Eμ-myc tumor-bearing WT mice 24 hours after vaccination compared with untreated mice. (C) IFN-γ levels in serum from WT, NKT cell–deficient (Jα18KO), and IL-12–deficient (IL-12p35KO) mice at various time points relative to vaccination. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 5 mice. ND indicates not detected. ***P < .0001 (unpaired t test). ns indicates not significant. Two or 3 independent experiments were performed.

Systemic IL-12–dependent IFN-γ production after vaccination is required for lymphoma growth inhibition. WT or genetic cytokine knockout mice were challenged with 1 × 105 Eμ-myc 299 tumor cells and treated on day 5 with irradiated, α-GalCer–loaded tumor cells, or left untreated. (A) Eμ-myc tumor burden in blood 19 days after tumor inoculation, in untreated or vaccine-treated WT, IFN-γKO, IL-12KO (p35KO and p40KO), and IL-18KO mice. As indicated, some WT mice received mAb-based depletion of IFN-γ or isotype control mAb (cIg). (B) Serum cytokine levels from Eμ-myc tumor-bearing WT mice 24 hours after vaccination compared with untreated mice. (C) IFN-γ levels in serum from WT, NKT cell–deficient (Jα18KO), and IL-12–deficient (IL-12p35KO) mice at various time points relative to vaccination. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 5 mice. ND indicates not detected. ***P < .0001 (unpaired t test). ns indicates not significant. Two or 3 independent experiments were performed.

Both NKT cells and NK cells contribute to IFN-γ production after vaccination

Intracellular staining of NKT cells, NK cells, and CD8 T cells, all shown to be critical in the antilymphoma immune response after vaccination (Figure 3), was performed to determine which population(s) was responsible for the systemic IFN-γ production after vaccination. The percentages of IFN-γ–positive NKT cells and NK cells were significantly increased 24 hours after vaccination in tumor-associated organs: peripheral lymph nodes and spleen (Figure 5A-B left panels; Figure 5C). For NKT cells, this increase was most prevalent in the spleen where up to 50% of all NKT cells stained positive for IFN-γ (Figure 5B). In addition, on a per-cell basis, the level of IFN-γ production, measured by mean fluorescence intensity, was significantly higher for both NKT cells and NK cells after vaccine treatment, in both lymph nodes and spleen (Figure 5A-B right panels). In contrast, only a very small percentage of CD8 T cells were producing IFN-γ at this time point (< 1%; Figure 5B). Therefore, NKT cells and NK cells, but not CD8 T cells, are the major producers of IFN-γ after administration of α-GalCer–loaded Eμ-myc tumors.

Both NKT cells and NK cells contribute to the rapid production of IFN-γ after vaccination. WT mice were challenged with 1 × 105 Eμ-myc 299 tumor cells and some treated on day 5 with irradiated, α-GalCer–loaded tumor cells. At 24 hours after vaccination, direct ex vivo IFN-γ production was assessed by intracellular staining of NKT cells, NK cells, and CD8 T cells isolated from peripheral lymph nodes (A) and spleens (B). Data are mean ± SEM (n = 5) of the percentage of IFN-γ–producing cells (left panels) and levels of IFN-γ (mean fluorescence intensity [MFI], right panels). ΔMFI = change in MFI after subtracting values from a naive, non–tumor-bearing WT mouse. (C) Representative flow cytometry plots of IFN-γ expression in NK cells (top panels) and NKT cells (bottom panels) from spleen. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

Both NKT cells and NK cells contribute to the rapid production of IFN-γ after vaccination. WT mice were challenged with 1 × 105 Eμ-myc 299 tumor cells and some treated on day 5 with irradiated, α-GalCer–loaded tumor cells. At 24 hours after vaccination, direct ex vivo IFN-γ production was assessed by intracellular staining of NKT cells, NK cells, and CD8 T cells isolated from peripheral lymph nodes (A) and spleens (B). Data are mean ± SEM (n = 5) of the percentage of IFN-γ–producing cells (left panels) and levels of IFN-γ (mean fluorescence intensity [MFI], right panels). ΔMFI = change in MFI after subtracting values from a naive, non–tumor-bearing WT mouse. (C) Representative flow cytometry plots of IFN-γ expression in NK cells (top panels) and NKT cells (bottom panels) from spleen. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

α-GalCer–loaded tumor vaccine approach is effective against other hematologic cancers

Therapeutic vaccination with irradiated, α-GalCer–loaded tumors results in effective antitumor immunity against at least 2 individual Eμ-myc–driven B-cell lymphomas (Figure 2). To investigate whether this strategy was effective against other oncogene-driven cancers, prophylactic and therapeutic vaccination was assessed in AML-ETO9a (AML) and Vk*myc (multiple myeloma), both tractable and transplantable models of different hematologic lineages. Loading α-GalCer onto AML-ETO9a tumor cells significantly suppressed the development of leukemia when transplanted into WT C57BL/6 mice (median survival, 48 days), compared with challenge with unloaded AML-ETO9a cells (median survival, 37 days; P = .006, log-rank test; Figure 6A). Therapeutic vaccination in WT mice with established leukemic burden (2 weeks after tumor cell inoculation) was also effective at suppressing disease development, resulting in increased overall survival (Figure 6B).

α-GalCer–loaded AML-ETO9a tumor cells is effective at suppressing leukemic tumor growth in both prophylactic and therapeutic vaccine settings. (A) WT mice (n = 5 per group) were challenged intravenously with 1 × 106 unloaded or α-GalCer–loaded AML-ETO9a GFP/luciferase-expressing tumors. (B) WT mice (n = 5 per group) were challenged with 1 × 106 AML-ETO9a tumor cells, and 2 weeks later some were treated with single administration of irradiated, α-GalCer–loaded autologous AML-ETO9a tumor cells (indicated by arrow). (A-B) Representative in vivo bioluminescent images of tumor (luciferase activity at 5 weeks) and corresponding quantification of tumor burden (bioluminescent photon counts; middle graphs) over time. Survival curves are shown to the right. Date are mean ± SEM. **P < .007 (unpaired t test, or log-rank test for survival). *P < .05 (unpaired t test, or log-rank test for survival). ns indicates not significant. Two independent experiments were performed.

α-GalCer–loaded AML-ETO9a tumor cells is effective at suppressing leukemic tumor growth in both prophylactic and therapeutic vaccine settings. (A) WT mice (n = 5 per group) were challenged intravenously with 1 × 106 unloaded or α-GalCer–loaded AML-ETO9a GFP/luciferase-expressing tumors. (B) WT mice (n = 5 per group) were challenged with 1 × 106 AML-ETO9a tumor cells, and 2 weeks later some were treated with single administration of irradiated, α-GalCer–loaded autologous AML-ETO9a tumor cells (indicated by arrow). (A-B) Representative in vivo bioluminescent images of tumor (luciferase activity at 5 weeks) and corresponding quantification of tumor burden (bioluminescent photon counts; middle graphs) over time. Survival curves are shown to the right. Date are mean ± SEM. **P < .007 (unpaired t test, or log-rank test for survival). *P < .05 (unpaired t test, or log-rank test for survival). ns indicates not significant. Two independent experiments were performed.

When Vk*myc tumor cells were loaded with α-GalCer before administration, no development of MM was detected in these mice with disease-free survival of at least 18 weeks, compared with median survival of 12 weeks in mice receiving unloaded Vk*myc cells (supplemental Figure 4A-B). In contrast to Eμ-myc and AML-ETO9a tumor models, therapeutic vaccination did not suppress the outgrowth of established Vk*myc-driven myeloma, despite high levels of vaccine-induced IFN-γ production (supplemental Figure 4C-D).

Irradiated Eμ-myc tumors loaded with β-ManCer causes prolonged tumor growth inhibition

There is evidence that analogs of α-GalCer and other glycolipids may induce equivalent or greater antitumor activity than α-GalCer.32,33 To determine whether alternative glycolipids loaded onto Eμ-myc tumor cells gave superior protection against Eμ-myc lymphoma, WT C57BL/6 mice with established lymphoma received irradiated Eμ-myc tumor cells loaded with either the C-glycoside analog of α-GalCer (α-C-GalCer), OCH or β-ManCer. Other than OCH, each of these glycolipids loaded onto tumor vaccine suppressed Eμ-myc tumor growth in the first 12 days after vaccination to similar levels as α-GalCer (Figure 7A). Tumor inhibition was maintained more effectively in mice receiving β-ManCer–loaded tumors, with significantly lower lymphoma burden at day 26 (19 days after vaccination) compared with mice receiving α-GalCer or α-C-GalCer–loaded tumors (Figure 7A). Interestingly, vaccination with β-ManCer–loaded tumors did not induce a spike of systemic IFN-γ, IL-12, or TNF-α, observed at 24 hours in mice receiving α-GalCer–loaded tumors (Figure 7B).

Loading Eμ-myc tumor vaccine with β-ManCer gives prolonged therapeutic effect. WT mice were challenged with 1 × 105 Eμ-myc 299 (A) tumor cells and 5 days later treated with single administration of irradiated, Eμ-myc tumor cells pulsed overnight with 500 ng/mL of the indicated glycolipids. (A) Mean ± SEM (n = 5) tumor burden in blood of Eμ-myc 299 tumor challenged mice after vaccine treatment. Middle and right panels: Individual mouse tumor burden at day 19 and 26 time point from panel A, with statistical evaluation. (B) Serum cytokine levels from Eμ-myc tumor-bearing WT mice 24 hours after vaccination with tumors loaded with the indicated glycolipids. ***P < .0005 (unpaired t test). **P < .005 (unpaired t test). *P < .05 (unpaired t test). ns indicates not significant. Two independent experiments were performed.

Loading Eμ-myc tumor vaccine with β-ManCer gives prolonged therapeutic effect. WT mice were challenged with 1 × 105 Eμ-myc 299 (A) tumor cells and 5 days later treated with single administration of irradiated, Eμ-myc tumor cells pulsed overnight with 500 ng/mL of the indicated glycolipids. (A) Mean ± SEM (n = 5) tumor burden in blood of Eμ-myc 299 tumor challenged mice after vaccine treatment. Middle and right panels: Individual mouse tumor burden at day 19 and 26 time point from panel A, with statistical evaluation. (B) Serum cytokine levels from Eμ-myc tumor-bearing WT mice 24 hours after vaccination with tumors loaded with the indicated glycolipids. ***P < .0005 (unpaired t test). **P < .005 (unpaired t test). *P < .05 (unpaired t test). ns indicates not significant. Two independent experiments were performed.

Discussion

Many lymphomas are aggressive cancers with high levels of patient relapse and mortality after treatment. This study addressed the urgent requirement for new therapeutic options by investigating a therapeutic vaccine approach in a mouse model of myc oncogene-driven B-cell lymphoma, used to represent equivalent oncogene initiated B-cell neoplasms in humans. An immune adjuvant strategy using the NKT cell ligand α-GalCer was implemented based on evidence that NKT cell stimulation leads to generation of potent antitumor immunity in a range of malignancies.34-36 Compared with previous studies using glycolipid pulsed tumor vaccines,15-17 our findings are distinguished in the following important ways. We show, for the first time, that single therapeutic vaccination with irradiated, α-GalCer–loaded autologous tumors substantially inhibited the development and outgrowth of aggressive, poorly immunogenic Eμ-myc B-cell lymphomas and significantly prolonged survival of mice. This strategy was effective against 2 independently derived and genetically different Eμ-myc lymphomas, indicating that therapeutic efficacy of the vaccine was not inherent to a specific lymphoma. By extensive in vivo mechanistic examination of immune effector cell and cytokine requirements for vaccine-induced antilymphoma activity, we revealed that components of both innate (NKT cell, NK cells) and adaptive (CD8 T cells) immunity were critical and nonredundant. Specifically, rapid and systemic NKT cell– and IL-12–dependent IFN-γ production in response to vaccination resulted in peripheral expansion of NKT cells and NK cells, and further IFN-γ production by both NKT cells and NK cells, which was IL-18 independent and critical for therapeutic efficacy of the vaccine. In addition, CD4 T cells enhanced vaccine efficacy; however, they were not critical, and γδ T cells in this setting were not required. Our work also extended a single report of the antitumor activity of β-ManCer, by showing that therapeutic vaccination with β-ManCer–loaded Eμ-myc tumor cells gives prolonged tumor growth suppression of established Eμ-myc lymphoma compared with treatment with α-GalCer–loaded tumors.

Coadministration of α-GalCer with tumor-associated antigens was previously shown to elicit potent tumor-specific CD8 T cells responses, as a result of enhancing the activation/maturation of DC.37,38 We adopted a whole tumor vaccine approach as specific tumor-associated antigens have not been identified for most tumors and this approach also has the advantage of providing a loading and delivery system for α-GalCer, allowing site-specific presentation of tumor-associated antigens and α-GalCer to host immunocytes. In contrast to most solid tumors, Eμ-myc B-cell tumors express CD1d, making these ideal candidates for loading with α-GalCer and in situ targeting by NKT cells. We did not directly compare the therapeutic efficacy of α-GalCer–loaded tumors and α-GalCer–loaded DCs; however, injection of soluble α-GalCer had no protective effect against Eμ-myc tumors.

Antilymphoma activity elicited by vaccine-induced immunity was dependent on the presence of NKT cells, NK cells, and CD8 T cells. These results corroborate previous findings that a combination of innate (NKT cell, NK cell) and adaptive (T cell) immunity is required for antitumor activity using this approach.16,17 Generation of antigen-specific adaptive immunity was supported by our observation that tumor-type specificity of the vaccine was important for therapeutic efficacy because injection of α-GalCer–loaded AML-ETO tumors gave no protection against Eμ-myc tumors. However, vaccination with a different clone of α-GalCer–loaded Eμ-myc tumors (4242) led to antitumor activity against Eμ-myc 299 tumors. Chung et al revealed an exclusive role for conventional CD4 T cells in mediating antitumor immunity in response to an α-GalCer–loaded tumor vaccine against A20 lymphoma.15 Depletion of CD4 T cells with mAb in their model was associated with loss of protective effect of the vaccine shown by a decrease in survival. We observed that depletion of CD4 T cells in the Eμ-myc model also altered the outcome of the vaccine; however, this abrogated effect was not as striking as when NKT cells, NK cells, or CD8 T cells were depleted (Figure 3). We have not ruled out the possibility that decreased effectiveness of the vaccine on CD4 depletion is simply because of deletion of the CD4+ subset of NKT cells, rather than removal of conventional CD4 T cells. Differences in the relative CD4 T-cell contribution observed in the Eμ-myc and A20 lymphoma models is unclear; however, is probably the result of disparity between the models. For example, A20 cells used by Chung et al are a passaged cell line with relatively slow in vivo growth kinetics compared with transplanted primary Eμ-myc cells.15 In addition, A20 lymphomas express unusually high levels of MHC class II39 and therefore are intrinsically better targets for CD4 T cell–mediated immunity. In contrast, Eμ-myc tumors express very low levels of MHC II (supplemental Figure 1), consistent with aberrant MHC II expression in many human B-cell malignancies.40 In this regard, Eμ-myc tumor immunogenicity more closely resembles human B-cell lymphomas than A20 tumors. Similarly, it is unclear why CD8 T cells were critical for inhibition of Eμ-myc but not A20 tumor growth after vaccination, but this may also be explained by the differences in MHC class I expression. Eμ-myc tumors express high levels of MHC class I, which is further increased by exposure to IFN-γ (supplemental Figure 1). In addition to conventional αβ T cells, we also investigated whether γδ T cells had any role in antilymphoma immunity elicited by the vaccine, based on our recent findings that γδ T cells are stimulated after administration of soluble α-GalCer and are required for optimal α-GalCer–induced immune responses.41 We found that antilymphoma immunity after vaccination with α-GalCer–loaded tumors was not affected by the absence of γδ T cells.

Production of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-12 and IFN-γ was critical for antilymphoma activity after vaccination with α-GalCer–loaded tumors. A large IL-12–dependent systemic release of IFN-γ occurred after vaccination (detected in serum at 24 hours), and the major contributors of IFN-γ were both NKT cells and NK cells. The target of IFN-γ is currently unknown. We speculate that the main antitumor activity of IFN-γ is a direct effect on Eμ-myc cells, which are IFN-γ receptor (IFN-γR) positive. The direct effects of IFN-γ on Eμ-myc cells are currently being investigated, and we have shown that IFN-γ treatment up-regulates MHC class I on these tumors. It is also likely that IFN-γ production is implicated in the cross-talk between immune cell populations as we show that maximal expansion of NKT cell and NK cell populations in the week after vaccination required IFN-γ. It is thought that IL-18 can synergize with IL-12 for optimal activation and IFN-γ production from NK cells29-31 ; however, a role for IL-18 production was not observed in this vaccine setting.

Although tumor loading with α-GalCer, α-C-GalCer, or β-ManCer all resulted in equivalent protection early, vaccination with β-ManCer–loaded tumors prolonged the suppression of Eμ-myc tumor growth. A recent study by O'Konek et al reported similar findings that, through NKT cell activation, β-ManCer injection was capable of inducing equivalent antitumor activities to α-GalCer against experimental lung metastases of B16F10 melanoma and CT26 colon carcinoma, in a NOS- and TNF-α–dependent manner.32 This was despite no substantial increases in cytokine production in vivo after treatment, including undetectable IFN-γ and TNF-α. In agreement with these findings, we could not detect IFN-γ, IL-12, or TNF-α 24 hours after vaccination with β-ManCer–loaded tumors, although it is possible that β-ManCer elicits different kinetics of immune cell activation and cytokine production, as previously reported for other glycolipids.42 Therefore, therapeutic efficacy of NKT cell vaccines incorporating Th1-biasing glycolipids, such as α-GalCer, is IFN-γ dependent; however, other glycolipids may possess distinct antitumor mechanisms. We are currently investigating mechanisms by which β-ManCer induces prolonged antilymphoma activity against Eμ-myc tumors, including the extent to which CD8 T-cell adaptive immunity is induced.

We demonstrated that the α-GalCer–loaded tumor vaccine approach was effective against other oncogene-driven mouse models of hematologic malignancies, such as the rapidly growing AML-ETO9a leukemia, resulting in significant survival advantage. Loading Vk*myc myeloma cells with α-GalCer was sufficient to prevent development of MM, but interestingly vaccination in mice with established MM was ineffective at reducing myeloma burden. Unlike the disseminated growth of Eμ-myc and AML-ETO9a tumors, Vk*myc tumors reside primarily in bone marrow. This may represent a microenvironmental niche that is refractory to the antitumor effects of vaccine-induced immunity. Indeed, the persistence and progression of myeloma are characterized by the development of an immune suppressive tumor microenvironment via cytokine production,43 tumor membrane PDL-1 expression,44 and down-regulation of NK cell activity.44,45 WT mice with established Vk*myc myeloma retained the capacity to produce IFN-γ after vaccination, shown by a spike in the serum at 24 hours, ruling out the possibility that development of transplanted Vk*myc tumors leads to a loss or permanent functional defect of the NKT cell population. Vk*myc cells retain expression of CD1d, which predicts effective targeting by NKT cells; however, unlike Eμ-myc tumors, MHC class I expression on Vk*myc cells is not altered by IFN-γ treatment (supplemental Figure 1). Therefore, eradication of Vk*myc tumors may be highly dependent on direct cytotoxicity by NKT cells rather than sensitivity to IFN-γ, which may explain why live α-GalCer–loaded Vk*myc cells were readily eliminated, whereas unloaded (parental) tumor cells failed to be targeted by NKT cells in the absence of ligand. This view is supported by the observation that WT mice vaccinated with α-GalCer–loaded Vk*myc cells were not protected to subsequent Vk*myc tumor challenge, suggesting that adaptive immunity was not sufficiently generated. We are currently investigating the functional capacity of NKT cells and NK cells in Vk*myc transgenic mice, which will shed light on the role for these innate lymphocytes in immune surveillance of spontaneously arising Vk*myc-driven myeloma.

In conclusion, a whole tumor vaccine strategy that harnesses the immune adjuvant properties of the NKT cell ligand α-GalCer is highly effective at suppressing growth of aggressive CD1d+ mouse B-cell lymphomas and other CD1d+ blood cancers that resemble oncogene-driven hematologic malignancies in humans. Although NKT cells constitute a small population in humans, it has been extensively shown that NKT cells are very potent regulators of cellular immunity, and NKT cells from cancer patients can be expanded and manipulated in vitro to stimulate antitumor immunity.46,47 Our approach is ideally suited for many hematologic malignancies, where a large number of tumor cells can be easily accessed from the blood or bone marrow, incubated immediately with α-GalCer, and irradiated before injection, thus providing a quick, inexpensive, patient-specific cancer vaccine. In addition, unlike many solid tumors, hematologic-derived cancer cells express CD1d, which facilitates loading with α-GalCer. Rapid translation into clinical investigation is possible given the current availability of clinical grade α-GalCer, which is deemed safe for use in humans,13,48,49 and the ability to assess vaccination directly in a de novo cancer setting of Eμ-myc and Vk*myc transgenic mice. Finally, determining whether an effective antitumor response to vaccination is reliant on the capacity of the vaccine to elicit IFN-γ production as well as the inherent IFN-γ sensitivity of a tumor may enable future prediction of patient-specific cancers likely to benefit most from this vaccine approach and identify potential strategies for combination immunotherapies.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Qerime Mundrea and Ben Venville for maintenance of the mice, Dale Godfrey for providing CD1d-tetramer, David Faulkner for SPEP analysis, Robert Schreiber for H22 and GK1.5 mAb, and Steven Porcelli, Robert Bittman, and Del Besra for glycolipids.

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (program grant). S.R.M. was supported by a Balzan Foundation Fellowship. M.J.S. was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Fellowship.

Authorship

Contribution: S.R.M. designed and conducted or supervised the experiments and wrote the manuscript; A.C.W. assisted with experimentation and data analysis and provided experimental feedback; K.S. and H.D. assisted throughout with experimentation and data management; C.P. performed IL-18 ELISA and provided experimental feedback; G.M.M. and J.S. derived the Vk*myc tumor cell clone 4929; M.C. and P.L.B. provided the Vk*myc transgenic mice; B.M. and M.B. engineered GFP- and luciferase-expressing Eμ-myc and AML-ETO9a tumor cells; J.Z. and S.W.L. provided the AML-ETO9a tumor model; and R.W.J. and M.J.S. provided the tumor models, critical input, and critical review of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mark J. Smyth, Cancer Immunology Program, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Locked Bag 1, A'Beckett St, East Melbourne, Victoria 8006, Australia; e-mail: mark.smyth@petermac.org; and Stephen R. Mattarollo, University of Queensland Diamantina Institute, R Wing, Building 1, Princess Alexandra Hospital, Woolloongabba, Queensland 4102, Australia; e-mail: s.mattarollo@uq.edu.au.

![Figure 5. Both NKT cells and NK cells contribute to the rapid production of IFN-γ after vaccination. WT mice were challenged with 1 × 105 Eμ-myc 299 tumor cells and some treated on day 5 with irradiated, α-GalCer–loaded tumor cells. At 24 hours after vaccination, direct ex vivo IFN-γ production was assessed by intracellular staining of NKT cells, NK cells, and CD8 T cells isolated from peripheral lymph nodes (A) and spleens (B). Data are mean ± SEM (n = 5) of the percentage of IFN-γ–producing cells (left panels) and levels of IFN-γ (mean fluorescence intensity [MFI], right panels). ΔMFI = change in MFI after subtracting values from a naive, non–tumor-bearing WT mouse. (C) Representative flow cytometry plots of IFN-γ expression in NK cells (top panels) and NKT cells (bottom panels) from spleen. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/120/15/10.1182_blood-2012-04-426643/4/m_zh89991297740005.jpeg?Expires=1765931632&Signature=jIZWqfZ~kiRQxwAgZWlR-B9CwrhIBouwU91sG8maDn6ygbeuSTAjbwX8dM-fHNQxPKdSia3xuURnsBqmeu2KxNXzgJvhIBDVWsKx9PFHq2k-ieR7TqK5KzoMaqXufoErjcFi1eNVl0jlmidGGiU1-ekWhffOIVsuDodoyhaLwCdEost8FMYDQ9bZGjI~vFHj-O~CXnW5~0X~r3YYmjZH7OMTf-nruSOV6j3VlKvbLKIK8zJRDz4MOhlDSs4U54S98MQE5KCTRl89Aw~6c7~kfZYsRmrztxvr0aDWG7Qwr0CJ00rSCgaPbKA78-cEDuEvBbQzJVYtuEnn7kyHaXH93Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal