Abstract

Polycythemia vera (PV) is a clonal disorder characterized by unwarranted production of red blood cells. In the majority of cases, PV is driven by oncogenic mutations that constitutively activate the JAK-STAT signal transduction pathway, such as JAK2 V617F, or exon 12 mutations or LNK mutations. Diagnosis of PV is based on the WHO criteria. Diagnosis of post-PV myelofibrosis is established according to the International Working Group for Myeloproliferative Neoplasms Research and Treatment criteria. Different clinical presentations of PV are discussed. Prognostication of PV is tailored to the most frequent complication during follow-up, namely, thrombosis. Age older than 60 years and prior history of thrombosis are the 2 main risk factors for disease stratification. Correlations are emerging between leukocytosis, JAK2(V617F) mutation, BM fibrosis, and different outcomes of PV, which need to be confirmed in prospective studies. In my practice, hydroxyurea is still the “gold standard” when cytoreduction is needed, even though pegylated IFN-alfa-2a and ruxolitinib might be useful in particular settings. Results of phase 1 or 2 studies concerning these latter agents should however be confirmed by the ongoing randomized phase 3 clinical trials. In this paper, I discuss the main problems encountered in daily clinical practice with PV patients regarding diagnosis, prognostication, and therapy.

Introduction

Polycythemia vera (PV) is a myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN).1 The abnormal myeloproliferation of PV is sustained by a constitutively active JAK-STAT signal transduction pathway, caused by the unique V617F mutation within exon 14 (∼ 95% of PV)2-5 and by different mutations within exon 12 (∼ 4% of PV) of the JAK2 gene.6,7 With lower prevalence, loss of negative regulation of JAK activation caused by LNK mutations (hot spot between codons 208 and 234),8 or by SOCS mutations9 or hypermethylation of CpG islands in SOCS1 and SOCS3,10 have been implicated in PV pathogenesis. The current view suggests that several other cooperating genetic hits might be required. Among others, mutations involving EZH211 or TET2,12 possibly interfering with epigenetic regulatory mechanisms, have been found in approximately 3% and in approximately 16% of JAK2(V617F)–positive PV, respectively.

The course of PV is mainly dominated by thrombosis, with an incidence estimated at 18 × 1000 person-years and accounting for 45% of all deaths, but also evolution to myelofibrosis (post-PV MF) and to acute myeloid leukemia (AML), both occurring with an incidence of 5 × 1000 person-years and accounting for 13% of deaths,13 warrant careful consideration. Comprehensive genotypic analyses of post-MPN AML cells identified several mutations14,15 involving IDH1-IDH2,16 TET2,17 IKZF,18 NRAS,19 TP53,20 and RUNX119,21 genes; furthermore, blasts, even arising in JAK2(V617F)–positive PV, have been shown to be JAK2(V617F)–negative in a significant proportion of patients,22 highlighting the genetic complexity of AML after PV.

In this manuscript, I discuss my approach to patients with PV with a focus on specific issues encountered in daily practice regarding diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment.

Diagnosis

The median age at presentation is in the sixth decade; patients younger than 50 years of age account for one-third of PV patients.23 Clinical presentation of PV may be recapitulated into 3 main scenarios: diagnosis by chance (most frequent), diagnosis after a thrombotic event (∼ 30%, 12% severe events),13,24 and diagnosis resulting from disease-related symptoms. Complete blood cell count (CBC) evaluation has a great relevance as a pan-myeloproliferative pattern (erythrocytosis with leukocytosis and/or thrombocytosis) is more consistent with PV than isolated erythrocytosis. Blood smear evaluation infrequently adds substantial information, even though a look at red cell morphology might help in borderline situations. Splenomegaly is present in approximately 30% to 40% of PV, mainly when PV is pan-myeloproliferative. In the case of splenomegaly with isolated erythrocytosis, I study the splanchnic district by ultrasound (US) or computed tomography (CT) scan to look for splanchnic vein thrombosis (SVT), even in asymptomatic patients. I do this imaging also in all PV patients with mild to severe upper abdominal quadrant pain or vague abdominal disturbances, as I have seen many PV patients with subacute SVT left undiagnosed.

Which criteria to apply for diagnosis of PV and of its evolutions?

In all patients with isolated erythrocytosis, I first explore causes of secondary polycythemia, such as smoking (by history and oxygen saturation), pulmonary or cardiac problems (by chest x-ray, lung function tests, echocardiography), overweight with nocturnal dyspnea (by polysomnography), or hepatic and renal tumors (by US scan). Assessing serum erythropoietin (EPO) level is an excellent discriminatory test, being high in secondary polycythemia and low in PV.25 To obtain reliable results of EPO measurements, blood sampling must be performed before the beginning of phlebotomies. When a patient displays a pan-myeloproliferative phenotype, I usually investigate PV first.

I use the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria to diagnose PV,1 as published in 2008, combining 2 major and 1 minor criteria or 1 major and 2 minor (Table 1). Actually, approximately 98% of PV diagnoses are covered by the 2 major criteria. Concerning red cell mass measurement, I do not use it as a diagnostic tool for PV, but the WHO classification system allows the diagnostic use of an elevated red cell mass more than 25% above mean normal predicted value, when desired. After diagnosis, I check CBC count and I visit patients from 3 to 6 times a year depending on treatment monitoring need, degree of disease control, and logistics. When a patient develops splenomegaly exceeding more than 5 to 10 cm from the costal margin, or reduces the need of phlebotomy or the dose of cytotoxic therapy to control PV, or when the blood smear reveals leukoerythroblastosis, I check the BM looking for disease evolution. To diagnose post-PV MF, I use the International Working Group for Myelofibrosis Research and Treatment criteria as published in 2008 (Table 2).26

WHO criteria for diagnosis of PV

Major criteria

|

Minor criteria

|

Major criteria

|

Minor criteria

|

The diagnosis of PV requires meeting either both major criteria and 1 minor criterion or the first major criterion and 2 minor criteria.

Hemoglobin or hematocrit > 99th percentile of method-specific reference range for age, sex, altitude of residence, or hemoglobin > 17 g/dL in men, 15 g/dL in women if associated with a documented and sustained increase of at least 2 g/dL from a person's baseline value that cannot be attributed to correction of iron deficiency, or elevated red cell mass > 25% above mean normal predicted value.

International Working Group for Myelofibrosis Research and Treatment criteria for the diagnosis of post-PV MF

Required criteria

|

Additional criteria (2 are required)

|

Required criteria

|

Additional criteria (2 are required)

|

Defined as hemoglobin value < 12 g/dL for female and < 13.5 g/dL for male.

What is the practical impact of the JAK2(V617F) mutation?

First, the presence of the JAK2(V617F) mutation helps in the diagnostic process of an erythrocytosis and is a major criterion for PV diagnosis. Regarding the JAK2(V617F) allele burden,27 although no standardized method of analysis is available to date28 and outcome should probably be adjusted for sex,29 PV patients have median values ranging from 30% to 40%, similar to those of patients with primary myelofibrosis (PMF) and higher than those with essential thrombocythemia (ET).30,31 In PV patients, I have always found interesting correlations between allele burden and clinical phenotype. A higher allele burden correlates unequivocally with enhanced myelopoiesis of the BM, with peripheral blood leukocytosis, and with splenomegaly, whereas it inversely correlates with platelet count.32-36 A clear correlation between hemoglobin levels and allele burden is not evident, possibly because many variables (eg, sex and iron status) can interfere with hemoglobin levels. Although allele burden quantification is not mandatory to diagnose PV, I generally analyze the JAK2(V617F) mutation by a quantitative RT-PCR–based allelic discrimination assay,34 studying the mutation on isolated neutrophils. Outside of a research setting, a qualitative test on whole blood leukocytes is a correct approach.37

When and why to study JAK2 exon 12 mutations in PV?

I check exon 12 mutations of JAK26 in case of V617F-negative erythrocytosis with low serum EPO levels or in case of pan-myeloproliferative V617F-negative PV. In a multicenter European study, we found that exon 12 mutations of JAK2 account for 4% of PV cases and that N542-E543del is the most frequent (30%) among the 17 mutations described.7 Irrespective of the underlying mutation, two-thirds of patients had isolated erythrocytosis, whereas the remaining subjects had erythrocytosis plus leukocytosis and/or thrombocytosis. To screen for exon 12 mutations of JAK2, the high resolution melting has been recently validated and has demonstrated its strength in routine mutation detection.38

Is there the need to investigate other mutations?

For the time being, there is no indication to study other PV-related mutations in routine clinical practice, although testing LNK mutations8 in the very restricted setting of PV cases without any JAK2 mutation might be of potential interest. I do not check for mutations involving TET2 or evolution-phase mutations involving IDH1-2, IKZF, NRAS, TP53, ASXL1, and RUNX1,39 given that the former do not display mutual exclusivity with JAK2 mutations and the latter do not predict evolution during chronic phase. In the case one claims for the full molecular profile of a patient, I suggest contacting national referral centers.

Is BM histopathology critical in PV?

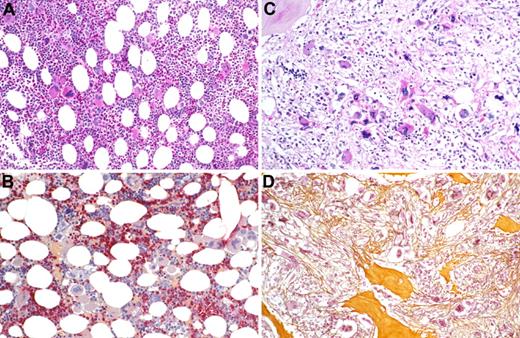

I usually receive 3 questions on this topic. The first is whether BM biopsy is necessary to diagnose PV. In patients with JAK2-mutated erythrocytosis and low EPO, BM biopsy is not required, but in all other situations BM biopsy is mandatory. Information one wishes to obtain from this examination regard age-adjusted cellularity and grade of myelofibrosis.40 The second is how to interpret the presence of any grade of BM fibrosis in PV at diagnosis. The rate of grade 1 reticulin fibrosis in PV at diagnosis ranges from 14%41 to 30%,42 and this does not imply per se a diagnosis of myelofibrosis. The third question is whether BM testing should be repeated on a regular basis in PV patients after diagnosis. I check the BM biopsy only in case of manifest signs of disease evolution, such as splenomegaly, leukocytosis, anemia, prolonged fever, weight loss, or night sweats. Figure 1 gives pathologic features of PV and post-PV MF at the corresponding time of diagnosis.

Bone marrow histopathology in polycythemia and postpolycythemia myelofibrosis. (A) Case of PV showing hypercellular BM with trilineage proliferation of all hematopoietic lineages, including prominent megakaryocytes (original magnification ×350). PAS indicates periodic acid-Schiff reaction. (B) Case of PV by immunohistochemistry revealing red-stained neutrophil granulopoiesis and dark-blue nucleated erythropoietic precursors as well as loose clusters of small to large megakaryocytes (original magnification ×350; AS-D-chloroacetate esterase reaction). (C) Case of post-PV myelofibrosis showing decrease in overall cellularity and only a few small and loose erythropoietic islets, abnormal megakaryocytes, and greatly extended stroma compartment (original magnification ×350). PAS indicates periodic acid-Schiff reaction. (D) Case of post-PV myelofibrosis revealing effacement of hematopoiesis by dense bundles of (yellow-brownish) collagen and reticulin fibers associated with osteosclerosis enclosing few dispersed megakaryocytes (original magnification ×350; Gomori silver impregnation technique).

Bone marrow histopathology in polycythemia and postpolycythemia myelofibrosis. (A) Case of PV showing hypercellular BM with trilineage proliferation of all hematopoietic lineages, including prominent megakaryocytes (original magnification ×350). PAS indicates periodic acid-Schiff reaction. (B) Case of PV by immunohistochemistry revealing red-stained neutrophil granulopoiesis and dark-blue nucleated erythropoietic precursors as well as loose clusters of small to large megakaryocytes (original magnification ×350; AS-D-chloroacetate esterase reaction). (C) Case of post-PV myelofibrosis showing decrease in overall cellularity and only a few small and loose erythropoietic islets, abnormal megakaryocytes, and greatly extended stroma compartment (original magnification ×350). PAS indicates periodic acid-Schiff reaction. (D) Case of post-PV myelofibrosis revealing effacement of hematopoiesis by dense bundles of (yellow-brownish) collagen and reticulin fibers associated with osteosclerosis enclosing few dispersed megakaryocytes (original magnification ×350; Gomori silver impregnation technique).

Looking for familial cases of erythrocytosis: when?

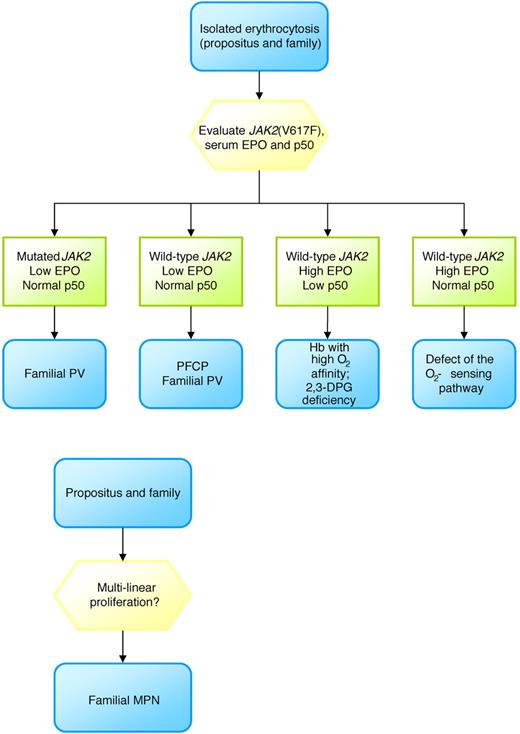

All MPN patients should be asked about family history of erythrocytosis or MPN. Basically, I categorize familial erythrocytosis into 2 main groups on the basis of serum EPO level: low EPO (primary familial and congenital polycythemia); and normal-high EPO (disorders of oxygen-sensing mechanisms, altered affinity of hemoglobin for oxygen, congenital cyanotic heart or lung disease).

Primary familial and congenital polycythemia is an autosomal dominant disease with mutational lesions (16 described so far)43 truncating the EPO receptor with subsequent loss of the negative regulatory domain leading to a final activation of the JAK2/STAT pathway.44,45 Patients with primary familial and congenital polycythemia have isolated erythrocytosis, low EPO, no splenomegaly, and a predisposition to severe cardiovascular (CV) problems.45 On the other hand, the oxygen-sensing pathway consists of different proteins involved in the regulation of erythropoietin production: hypoxia inducible factor (HIF), von Hippel Lindau protein (VHL), and prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins (PHDs). After the first defect of the oxygen-sensing pathway involving the VHL gene was described,46 different patterns of mutations involving the VHL, PHD, and HIF genes have been described.47-49 The disease is autosomal recessive or dominant, characterized by erythrocytosis, normal-high EPO, frequent headache, and thrombosis.50 Other causes of inherited erythrocytosis with high EPO include inherited conditions that increase the affinity of hemoglobin for oxygen, including high O2 affinity hemoglobin disorders and deficiency of 2,3-DPG (I recommend screening for P50 level on venous blood samples), methemoglobinemia (I recommend measurement of arterial blood gases and pulse oxymetry in case of cyanosis), and cyanotic congenital heart disease (I recommend a cardiology consult). Finally, familial clustering of PV cases may occur with a frequency of approximately 6% to 7%; these cases mimic sporadic PV in terms of complications and disease evolution.51 I follow the flow chart reported in Figure 2.

Toward a simplified diagnostic algorithm

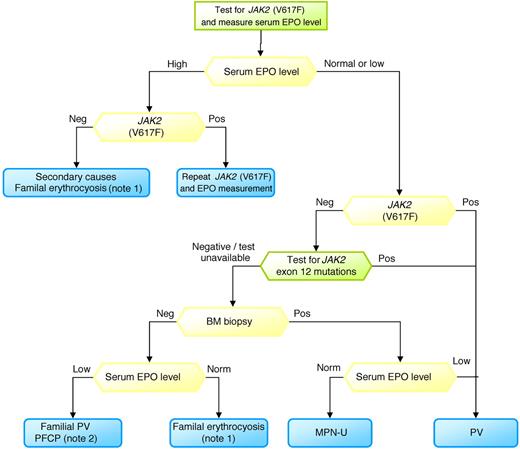

Figure 3 reports the steps I undertake to diagnose PV. As some tests may not be widely available outside the research setting, I suggest contacting national referral centers to perform molecular tests and to obtain instructions for blood sampling and delivery: this approach should maximize the uniformity of results.

Diagnostic approach to erythrocytosis. Note 1 indicates familial erythrocyosis (eg, disorders of O2-sensing mechanisms, altered affinity of hemoglobin for O2); note 2, primary familial and congenital polycythemia (PFCP).

Diagnostic approach to erythrocytosis. Note 1 indicates familial erythrocyosis (eg, disorders of O2-sensing mechanisms, altered affinity of hemoglobin for O2); note 2, primary familial and congenital polycythemia (PFCP).

Prognostication in PV

Life expectancy of PV patients is reduced compared with that of the general population, as demonstrated in a study including 396 PV patients followed for a median time of 10 years52 and as recently confirmed.53 As thrombosis is the most frequent complication, there is rationale for stratifying PV patients according to the risk of thrombosis.

Risk factors for thrombosis

There is a general agreement among investigators to consider age older than 60 years at diagnosis and a history of vascular events as the 2 prognostic risk factors for thrombosis in PV (Table 3).54,55 The European Collaboration on Low-Dose Aspirin in Polycythemia Vera (ECLAP) study reported that patients younger than 65 years without prior thrombosis have an incidence of thrombosis of 2.5 × 100 persons/year, those older than 65 years or with prior thrombosis have an incidence of 5.0 × 100 persons/year, and patients older than 65 years with prior thrombosis have an incidence of 10.9 × 100 persons/year.56

Risk categories in PV

| Category . | Characteristics . |

|---|---|

| Low risk | Age < 60 y and no history of thrombosis |

| High risk | Age ≥ 60 y or history of thrombosis |

| Category . | Characteristics . |

|---|---|

| Low risk | Age < 60 y and no history of thrombosis |

| High risk | Age ≥ 60 y or history of thrombosis |

I take CV risk factors (arterial hypertension, smoking, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, obesity) into consideration, even though I do not include them into a formal risk stratification model for PV. Among the aforementioned factors, smoking is the only documented risk factor associated with an increased risk of thrombosis in PV.56

Concerning the CBC count, hematocrit levels up to 50% and high platelet count are not associated with thrombosis.13 On the other hand, extreme thrombocytosis per se might provoke an excess of bleeding because of acquired von Willebrand disease. In the very few patients with platelet counts exceeding 1500 × 109/L, I consider starting cytoreduction in PV, as well as in ET, although I tend to use a higher cut-off in young patients. Concerning leukocytosis, an analysis of the ECLAP trial13 showed that patients with a leukocyte count exceeding 15 × 109/L have a significant increase of myocardial infarction compared with those having leukocyte counts less than 10 × 109/L. Regarding mutational status and allele burden, I do not consider a high JAK2(V617F) allele burden as a potential risk factor for thrombosis.42–35 Regarding PV patients who carry exon 12 mutations of JAK2, I apply the same risk stratification of other PV patients (Table 3).7

Risk factors for disease evolution

Approximately 10% of PV patients evolve into post-PV MF (also referred as spent-phase PV),57 with progressive splenomegaly, MF-related symptoms, anemia, and leukopenia/leukocytosis. MF evolution is difficult to be predicted, but leukocyte count greater than 15 × 109/L has been documented as a risk factor for disease evolution.57 In a prospective study including 338 PV patients, allele burden greater than 50% implied a higher risk of evolution to MF.42 When BM biopsy is performed, I suggest to consider the recent evidence that PV patients with fibrosis have an approximately 3-fold higher risk of developing post-PV MF than those without.41 I check all these parameters, but for the time being, I do not use them for treatment decisions. Evolution to AML is a rare event without any specific risk factor to be looked for at diagnosis. However, I think that advanced age (as a sign of genomic instability) and a high leukocyte count (as a sign of myeloproliferation) might be of interest.24,58-60

Risk factors for survival

A model to predict survival has been reported in PV indicating that advanced age, leukocytosis, and prior venous thrombosis affect survival.61 As an example, based on this model, a 60-year-old PV patient with leukocytosis has an expected median survival of approximately 11 years, showing the limits of available treatments.

Risk factors for survival after diagnosis of post-PV MF

When PV progresses to post-PV MF, my prediction of survival is based on the dynamic prognostic score we developed in post-PV MF patients.57 This model is based on 3 risk factors: hemoglobin level lower than 10 g/dL, leukocyte count greater than 30 × 109/L, and platelet count lower than 100 × 109/L. The low-risk group includes patients without risk factors, whereas higher-risk categories include patients with 1, 2, or 3 risk factors. When a patient acquires 1 risk factor during follow-up, his/her survival worsens (4.2-fold). However, many investigators are more confident applying prognostic systems developed in PMF, International Prognostic Scoring System, Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System, or Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System-plus.62-64

Therapy

The goal of therapy is to prevent thrombosis occurrence and recurrence, to delay, if possible, evolution into MF or AML, and to control disease-related symptoms. On behalf of the European LeukemiaNet, different levels of response have been defined in PV, namely, clinicohematologic, molecular, and histologic responses.65 However, because these criteria were established to standardize design of clinical studies and reporting of results, they should not be applied in clinical practice.

I continue to consider 45% as the cut-off hematocrit value to control PV, although the ECLAP13 and PVSG-0166 studies did not disclose any advantage in maintaining hematocrit values less than 50% to 52%. The multicenter randomized and controlled Cytoreductive therapy in PV trial67 is aimed at defining the benefit/risk profile of cytoreductive therapy given to maintain hematocrit less than 45% versus 45% to 50%. The Cytoreductive therapy in PV will clarify the best cut-off for hematocrit in PV. Besides hematocrit control, the aim of therapy should be to normalize leukocyte count, platelet count, and spleen size, whenever increased. Indeed, hematocrit response seems not to result in better survival or lower thrombosis and bleeding rates.68 On the contrary, having no response in terms of leukocyte count was associated with a higher risk of death (hazard ratio = 2.7), whereas lack of response in platelet count involved a higher risk of thrombosis and bleeding.68

My treatment strategy

The treatment strategy in PV patients consists of combining 4 elements: modification of CV risk factors, antiplatelet therapy, phlebotomy, and cytoreduction.

Correction of CV risk factors

A definitive causative/contributory role for CV risk factors on the incidence of vascular events in PV is not yet defined, except for smoking.69 However, one may assume that arterial hypertension, diabetes, smoking, hypercholesterolemia, and obesity can modify the vascular risk in PV patients in (at least) the same way as in non-PV subjects. Given that CV risk factors are PV-independent, I do not use cytotoxic therapy in patients harboring them, but I treat CV risk factors according to the corresponding guidelines and I check patients' adherence to these indications during follow-up.

Antiplatelet therapy

Aspirin is my preferred antiplatelet drug in PV for different reasons. An increased biosynthesis of thromboxane has been reported in PV, and 1 of the cellular effects of aspirin on platelet aggregation is the reduction of thromboxane biosynthesis.70 The ECLAP trial studied 518 PV patients randomized to low-dose aspirin (100 mg/day) or placebo.13 This study demonstrated a significant advantage for aspirin in terms of nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, pulmonary embolism, major venous thrombosis, or death from CV causes (relative risk = 0.40) with a higher risk of any bleeding (relative risk = 1.82), although the latter did not reach statistical significance. On the basis of this information, I use low-dose aspirin (100 mg/day) in PV patients at any risk unless contraindicated, and I withdraw aspirin in case of bleeding or gastric intolerance.

Phlebotomy

I recommend phlebotomy in all patients with PV and as single treatment for hematocrit control in those at low-risk for thrombosis without overt signs of myeloproliferation. A Polycythemia Vera Study Group (PVSG) randomized trial compared phlebotomy alone with radiophosphorus plus phlebotomy or chlorambucil plus phlebotomy.66 Although comparators are obsolete treatments in PV, patients treated with phlebotomy alone had a better survival but displayed an excess of mortality within the first 2 to 4 years, principally caused by thrombotic complications. I start phlebotomy at diagnosis by withdrawing 250 to 400 mL of blood every other day (lower quantity and frequency in older patients or in case of CV disease) until hematocrit reaches 40% to 45%. Once hematocrit normalization has been obtained, I check CBC every 4 to 8 weeks. Overusing phlebotomy, iron deficiency might be induced resulting in abnormal RBC morphology and eventually reactive thrombocytosis. In these cases, I generally do not supplement with iron, with the exception of very few patients with symptomatic iron deficiency who I treat with no more than 5 to 10 days of iron. I do not consider secondary iron deficiency as a reason for starting hydroxyurea (HU).

Cytoreductive therapies: the conventional approach

I consider cytoreductive therapy at diagnosis when patients are at high risk of thrombosis (age older than 60 years and/or prior thrombosis), or in the presence of symptomatic splenomegaly, platelet count higher than 1500 × 109/L, unexplained leukocytosis exceeding 20 to 25 × 109/L, or disease-related symptoms. I also begin cytoreductive therapy during the course of the disease in low-risk patients who shift to the high-risk category or develop progressive leukocytosis or thrombocytosis, enlargement of spleen, uncontrolled symptoms, or intolerance to or high need of phlebotomy.

I use HU, an oral antimetabolite that prevents DNA synthesis by inhibiting the enzyme ribonucleoside reductase, in all age PV patients who need cytoreductive therapy. The starting dose of HU is 15 to 20 mg/kg per day until response is obtained. In general, I give HU at a dose ranging from 1000 mg daily to 1500 mg daily according to the extent of myeloproliferation (the higher dose in case of leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, and splenomegaly), to the symptomatic burden and to the urgency (critical situation, surgery). I recommend female patients on HU to avoid pregnancies. After obtaining a response, a maintenance dose should be administered to keep the CBC within the normal range using the lowest possible dose. I check CBC monthly and, in steady state, every 3 months. I do not expect particular toxicities, and I warn patients about skin and nail alterations, potential leg ulcers, and macrocytosis of red blood cells. In my practice, I have seen very few cases of HU-induced fever and gastrointestinal toxicity, such as diarrhea or vomiting.

I prescribe HU because it is effective in preventing thrombosis, although this notion is derived from randomized clinical trials in ET. A pivotal trial performed in 114 ET patients at high risk for thrombosis compared HU with no therapy.71 After 27 months of follow-up, patients receiving HU had less thrombotic episodes (3.6%) than controls (24%). In another trial in ET, HU plus low-dose aspirin (100 mg daily) was compared with anagrelide (selective platelet-lowering agent) plus low-dose aspirin in 809 high-risk patients observed for a median follow-up of 39 months.72 Patients randomized to HU had less major thromboses (arterial or venous) than those treated with anagrelide.

In PV, HU (51 patients) was compared with phlebotomy (134 patients) in a PVSG trial.73 There were no significant differences in outcomes between the 2 groups, although the HU-treated patients developed more AML (9.8% vs 3.7%) and less MF (7.8% vs 12.7%). In PV, large studies have focused on the risk of AML. I generally discuss the following studies with my patients. (1) The ECLAP trial was conducted on 1638 PV and found that the incidence of AML was 0.29 × 100 patient/years for HU and 1.8 × 100 patient/years for other cytotoxic drugs (median observation before study enrollment 3.5 years, after enrollment 2.8 years) and did not disclose any difference between HU and no therapy.58 (2) Mayo Clinic investigators found that in 459 PV patients HU does not increase the rate of AML compared with no therapy.59 (3) The last update of the prospective randomized French Polycythemia Study Group trial74 showed that the cumulative incidence of AML/myelodysplastic syndrome at 20 years was 16.6% for patients treated with HU and 49.4% for patients treated with pipobroman.53 (4) I find of relevance the Swedish population-based study on 11 039 MPN patients with 162 post-MPN AML cases.75 Investigators found that 25% of AML patients were never exposed to cytotoxic drugs, that HU at any dose is not associated with an increased risk of AML, and that only an increasing cumulative dose of alkylators is associated with AML.

During follow-up, patients may become resistant to HU: the figure has been estimated at 11.5% after a median of 5.8 years from diagnosis and this implies a 5.6-fold increase in the risk of death.68 On the basis of these data, I start considering this cohort of patients as potential candidates for investigative trials. However, in my day-to-day clinical practice, I shift patients resistant or intolerant to HU to IFN if younger or to pipobroman24 or busulphan if older following the European LeukemiaNet recommendations.55

Is IFN an alternative to HU?

IFN is contraindicated in patients with thyroid and/or mental disorders. IFN is commonly administered subcutaneously at the dose of 3 million units daily until achievement of response. CBC should be recorded monthly. Pegylated (Peg) IFN-alfa-2a is given at a starting dose of 45 μg weekly; and in patients who fail to achieve a response after 12 weeks, the dose is increased to 90 μg and subsequently to 135 μg weekly. Afterward, therapy has to be adjusted at the lowest dose that maintains response and monitored following IFN-specific guidelines.

European LeukemiaNet55 recommended HU or IFN as first-line cytoreductive therapy at any age. Peg-IFN-alfa-2a was considered on the basis of the potential advantage in terms of JAK2(V617F) allele burden reduction.76 Indeed, peg-IFN has been reported to reduce the V617F load in 48% and to fully abrogate it in 24% of 37 PV patients at diagnosis. Overall hematologic responses was excellent (95%), whereas 24% of patients discontinued Peg-IFN for toxicity. Similar results were also obtained in 40 patients treated after a median time of approximately 5 years from PV diagnosis.77 Overall hematologic response rate was 80%, and abrogation of the V617F clone occurred in 14%.

I think that only ongoing trials comparing HU with Peg-IFN will clarify the indication of IFN in the clinical practice of PV patients. For the time being, I suggest using IFN in particular situation of PV: (1) high-risk females with childbearing potential, avoiding peg-IFN while pregnant; (2) high-risk young patients who refuse HU because of the inflexible fear that HU favors leukemic evolution; and (3) second-line therapy after HU intolerance/resistance in high-risk young people. In all these cases, I inform my patients that IFNs are not approved for PV, at least in my country.

JAK inhibitors in PV: a potential opportunity for some patients

Ruxolitinib is an oral JAK1-2 inhibitor now approved in the United States for myelofibrosis.78 Ruxolitinib-results in PV can be summarized as follows79 : (1) 34 patients with advanced PV (median PV duration, 10 years) received ruxolitinib over a median time of 21 months; (2) ruxolitinib-treated patients achieved a hematocrit less than 45% in 97% of cases, more than 50% spleen reduction in 80%, leukocytosis normalization in 73%, thrombocytosis normalization in 69%, and a complete response (normal hematocrit, platelets, leukocytes, spleen size)65 in 50%. Patients also obtained rapid improvement in patient-reported symptom scores; (3) 82% of patients were still on treatment at 21 months of therapy; (4) no grade 4 adverse events have been reported; (5) at the time of reporting, a few patients obtained a reduction of the V617F load exceeding 50%; and (6) ruxolitinib down-regulates leukocyte alkaline phosphatase expression in patients with PV or ET, and this is compatible with a decrease of leukocyte activation and a potential effect on thrombosis.80 A randomized phase 3 trial comparing ruxolitinib to best available therapy is ongoing and will clarify the role of ruxolitinib in the setting of PV patients intolerant or resistant to HU.

The majority of PV patients are well maintained over time with HU, and for them I do not favor any investigative trial unless the experimental drug provides evidence of clonal suppression. On the other hand, some patients may lose or not achieve response, develop symptomatic splenomegaly without evidence of evolution into post-PV MF, or have uncontrolled pruritus. These patients may benefit from ruxolitinib independently of the not yet demonstrated suppressive potential on the PV-clone.

Critical situations

SVT

In patients with SVT, the diagnosis of PV might be masked by coexisting hypersplenism and bleeding; and in most cases, the CBC is normal.81 Medical treatment of SVT includes low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) followed by long-life oral anticoagulation (to keep the international normalized ratio between 2.0 and 3.0). For PV control, I use HU as in high-risk PV cases modulating the dose on the CBC. Warning about pregnancy is recommended in this context,55 and decision should be taken on a case-by-case basis balancing the spleen volume impact on the uterus, the risk of additional vascular complications for the mother, with the possibility to follow pregnancy with LMWH and IFNs. A team of expert in MPN, thromboembolism, obstetrics, and hepatology is required for the discussion. In cases of PV with SVT, I recommend considering intensive management in agreement with the local hepatology team guidelines (transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, angioplasty with or without stenting, surgical shunts, and liver transplantation).

Surgery

I consider this situation at high risk as approximately 8% of PV and ET patients develop fatal thrombosis or hemorrhage after surgery.82 In elective surgery, I prepare my patients trying to achieve the best possible CBC (normalization or near-normalization) with HU, even in low risk PV patients treated solely with phlebotomy. I use prophylactic LMWH according to guidelines for the specific intervention.

Pregnancy

Differently from ET,83 pregnancy in PV is not usual because of the higher median age of patients. I explain to both patient and partner that PV may increase the risk of abortion and that it might be better for the fetus to avoid any type of cytotoxic agent to control PV, with the exception of IFN. I follow ELN recommendations,55 by maintaining hematocrit less than 45% with phlebotomy, adding aspirin if not contraindicated and LMWH after delivery until 6 weeks postpartum, adding LMWH during pregnancy in the case of previous major thrombosis or severe pregnancy complications, and considering IFN if platelet count is greater than 1500 × 109/L or prior severe bleeding.

Pruritus

No effective therapies are available for pruritus, a seriously debilitating although short-living symptom. Antihistamines are largely ineffective. In selected cases, photochemotherapy using psoralen and ultraviolet A light, may be successful. IFNs84 and ruxolitinib78 are effective in controlling pruritus.

Disease evolution

I treat post-PV MF as PMF tailoring treatment to anemia, splenomegaly, and constitutional symptoms, which are considered pressing issues in MF.55 I use steroids or danazol to treat anemia.

Pomalidomide seems a promising agent for anemia.85-88 For the control of myeloproliferation and symptoms in post-PV MF, HU is mostly ineffective almost all in patients treated with HU during PV phase.

Among JAK2 inhibitors, ruxolitinib (JAK1, JAK2 inhibitor, orally bioavailable)78,89,90 has been extensively studied, and it is now approved for MF in United States. SAR30250391 is currently under placebo-controlled phase 3 randomized trial, whereas other molecules are being evaluated in phase 1 or 2 trials.40 Of 152 MF patients treated with ruxolitinib in a phase 1 or 2 trial, 48 had post-PV MF.76 Clinical improvement of spleen size (≥ 50% reduction from baseline) was obtained in 44% of patients at 3 months, and responses were maintained at 12 months in more than 70% of patients. The majority of patients had more than 50% improvement in constitutional symptoms. Nonhematologic toxicity occurred in less than 6% and was usually grade 2. At a dose of 15 mg twice a day, grade 3 reversible thrombocytopenia occurred in 3% of patients and anemia in 8% of red blood cell transfusion-independent patients. Two randomized trials with ruxolitinib were conducted in MF: COMFORT I,88 comparing ruxolitinib with placebo (115 MF: 32 post-PV MF), and COMFORT II,89 comparing ruxolitinib with best available therapy BAT (146 MF: 33 post-PV MF). The primary endpoint was the number of subjects achieving more than or equal to 35% reduction in spleen volume from baseline to week 24 for COMFORT I and to week 48 for COMFORT II. The primary endpoint was achieved in 41.9% (ruxolitinib) versus 0.7% (placebo) in COMFORT I and in 28.5% (ruxolitinib) versus 0% (BAT) in COMFORT II. A reduction of total symptom score was obtained in 45.9% of ruxolitinib-treated patients and in 5.3% of placebo-treated patients. Finally, COMFORT II demonstrated that ruxolitinib was more effective than BAT in post PV-MF as well as in PMF.90 I will use ruxolitinib in all post-PV MF patients with splenomegaly and/or with disease-related symptoms, except in younger patients candidates to allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.92-97

AML post-PV is an aggressive phase of the disease, which is not curable in the majority of patients.98 Experimental therapies should be considered. I generally apply a de novo AML-like induction chemotherapy only in young patients potentially candidates for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Future directions

In recent years, great insight has been gained into the understanding of the pathogenesis of PV with the identification of the JAK2(V617F) mutation, of exon 12 mutations of JAK2 and of LNK mutations, but a minority (< 1%-2%) of patients with PV still remains without a known molecular alteration. In 2008, the WHO provided useful criteria to define PV; and in 2008, the International Working Group for Myeloproliferative Neoplasms Research and Treatment defined post-PV MF diagnostic criteria. Advances have also been made in terms of prognostication, although we still use age older than 60 years and prior thrombosis as the 2 risk factors to predict thrombosis. Leukocyte count, V617F allele burden, and BM histopathology seem really promising, but they need to be validated in prospective studies. Concerning therapy, HU is still my “gold standard,” although peg-IFN and ruxolitinib may be useful in particular settings of patients, with the cautionary note that results of phase 1 or 2 studies still need to be confirmed by the ongoing randomized clinical trials.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Prof Mario Lazzarino, past Director of the Division of Hematology of the University of Pavia, where the author worked for many years, for all aspects of his scientific work in the field of MPN. He has been a great teacher and advisor and, without his contribution and guidance in his career, the author would not have the opportunity to write this paper. The author also thanks Prof Jurgen Thiele and Prof Hans Michael Kvasnicka for providing BM figures and helpful interpretation and Dr Margherita Maffioli and Dr Domenica Caramazza from the author's Division of Hematology for many helpful discussions.

F.P. was supported by Associazione Italiana contro Leucemie, Linfomi, Mieloma, Varese Onlus.

Authorship

Contribution: F.P. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: F.P. serves as coinvestigator on many clinical trials, including those that are industry-sponsored, such as pomalidomide (Celgene), INCB018424 (Incyte), ruxolitinib (Novartis), panobinostat (Novartis), and SAR302503 (Sanofi-Aventis).

Correspondence: Francesco Passamonti, Division of Hematology, Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital Ospedale di Circolo e Fondazione Macchi, Viale L. Borri 57, 21100 Varese, Italy; e-mail francesco.passamonti@ospedale.varese.it.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal