Abstract

The cause of immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) remains unknown. Studies have suggested immunizations as possible triggering factors of ITP through molecular mimicry. This case-control study explored potential associations between adult ITP and various routinely administered vaccines. A network of internal medicine and hematology centers across France recruited 198 incident (ie, newly diagnosed) cases of ITP between April 2008 and June 2011. These cases were compared with 878 age- and sex-matched controls without ITP recruited in general practice. Information on vaccination was obtained from patients' standardized telephone interviews. Sixty-six of 198 cases (33.3%) and 303 of 878 controls (34.5%) received at least 1 vaccine within the 12 months before the index date. We found no evidence of an increase in ITP after vaccination in the previous 6 or 12 months (adjusted odds ratio [OR] for the previous 12 months = 1.0; 95% confidence interval, 0.7-1.4). When the 2-month time window was used, higher ORs were observed for all vaccines (OR = 1.3). This increase was mainly attributable to the vaccination against diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis-poliomyelitis (OR = 1.5) and was not statistically significant. The results of the present study show that in an adult population, the exposure to common vaccines is on average not associated with an observable risk of developing ITP.

Introduction

Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is an autoimmune disease characterized by low platelet counts due to increased destruction and impaired platelet production, partially related to the presence of autoantibodies directed toward platelet-membrane antigens.1 ITP manifestations include various degrees of cutaneous and/or mucosal purpura; life-threatening hemorrhages occur in less than 5% of adult patients.2 Onset is frequently insidious and low platelet counts often last beyond 6 months.3 In adults, the incidence of ITP is approximately 3.3 per 100 000 person-years.4,5

Studies have suggested that immunizations could be involved in the development of autoimmune disorders.6 This could be because of molecular mimicry, in which antigens of the host are recognized as being similar to antigens of the immunization, thus provoking the development of autoantibodies.7,8 Although several population-based studies have described an association between the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine and ITP in children,9-12 published evidence concerning the risk associated with other vaccines or with vaccination in adults is sparse and limited to a few case reports.13-17 The risk of ITP associated with adult vaccines therefore remains controversial. The objective of this prospective case-control study was to explore the incidence of ITP in relation to all vaccination in adults, with a special emphasis on vaccines against influenza (the injectable/killed type only) and diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis-poliomyelitis (DTPP).

Methods

Patients

This case-control study prospectively recruited consecutive patients with newly diagnosed ITP at 22 internal medicine and hematology centers in continental France and compared them with controls recruited from general practice settings. Cases and controls were recruited from the same geographically diverse areas. All participants (cases and controls) provided informed written consent to participate in the study, were 18-79 years of age, could read French, and were capable of answering questions by a qualified telephone interviewer. Cases and controls were excluded from the study if they had a history of thrombocytopenia.

The study protocol was submitted to the ethical review committee of Paris-Ile de France III (Comité de Protection des Personnes Ile de France III) and was approved by the French Data Protection Authority (Commission Nationale de l'Informatique et des Libertés). All participants signed an informed consent form in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study population

Case subjects.

We conducted this study using patient data retrieved from the Pharmacoepidemiological General Research on ITP (PGRx-ITP) registry, a French nationwide registry. A total of 28 university and major regional hospitals in France with an internal medicine or hematology center treating adults were approached to take part in the PGRx-ITP registry and 22 agreed to participate. Clinical research assistants randomly audited the centers for compliance with the study protocol.

Consecutive subjects presenting with first lifetime clinical manifestations strongly suggestive of newly diagnosed ITP with platelet counts below 100 G/L according to the consensual international criteria18 were identified prospectively and independently of any risk factor or drug exposure. ITP diagnosis was made according to the American Society of Hematology diagnostic criteria.1 Patients who were not healthy aside from their symptoms of ITP were excluded. Exclusion criteria were: other disease(s) known to be associated with ITP, such as HIV or hepatitis C virus infection, lymphoproliferative disorders, thyroid or liver disease, definite systemic lupus erythematosus (≥ 4 American College of Rheumatology criteria),19 and definite antiphospholipid syndrome.20 Patients with isolated positive antinuclear Abs (titer > 1/80 using HEP2 line cells) without signs of systemic lupus erythematosus or with isolated positive antiphospholipid Abs (anticardiolipin Abs > 40IU as determined by ELISA test and/or anti-β2 Gp1 Abs and/or lupus anticoagulant) without history of thrombosis were not excluded. Uncertain diagnoses were reviewed by a board of 2 independent certified hematologists who were blind to medications and vaccinations. Cases of newly diagnosed ITP were classified as definite or possible or were rejected by the board. Cases were classified as definite when a normal platelet count was available within the 12 months preceding the date of ITP diagnosis. In the absence of any available previous platelet count, cases were classified as possible only when thrombocytopenia manifested by an abrupt onset of spontaneous and unusual bleeding manifestations without any prior history of bleeding. Cases revealed by a fortuitous discovery of thrombocytopenia without any bleeding symptoms were rejected and only definite and possible cases were included in the analysis. The recruiting specialist (hematologist/internist) completed a web-based medical data form for each case recruited.

Centers participating in the PGRx-ITP registry were contacted at least every 2 months by external research assistants to audit the completeness of the registry with eligible patients seen in the participating centers between April 1, 2008 and June 13, 2011.

For cases, the index date was the date of the first clinical sign or symptom suggestive of ITP reported by the recruiting physician. For controls, the index date was the date of consultation with the recruiting general practitioner (GP).

Control subjects.

A total of 216 GPs from the same regions as the internal medicine/hematology centers participated in this study. They were randomly selected by region from a national list of GPs in France. The GPs were instructed to recruit the first male and female patient presenting to their practice within the following age strata: 18-34, 35-49, 50-64, and 65-79 years. Patients were recruited regardless of the reason for the consultation and independently of any morbidity or exposure criteria. A registry of 10 808 subjects called referents was constituted. All subjects fulfilling the inclusion criteria and not meeting any of the exclusion criteria were identified independently by the research team. Controls were randomly selected from this registry of referents and matched on age (± 2 years), sex, region of residence (northern or southern France), index date (date of first symptoms for the cases and date of consultation for the referents ± 2 months) and season of the index date (spring/summer: February 16 to September 14; fall/winter: September 15 to February 15). Matching by season ensured that cases and controls were compared for similar seasons and therefore had similar opportunities to be vaccinated against influenza. Controls were recruited during the same calendar time period as the ITP cases. A maximum of 5 controls were matched to each case using an iterative matching process, with a control being dropped from the pool after matching.

Physicians were requested to complete an electronic medical data form that included medical information on the patient (chronic diseases and comorbidities, medical risk factors, biologic data, and current prescriptions and prescriptions for the previous 2 years).

Assessment of vaccination

All participants recruited from the PGRx-ITP registry and the PGRx-GP database provided written informed consent for their GP to provide their prescriptions for the previous 2 years. Furthermore, cases and controls agreed to participate in an in-depth, standardized telephone interview covering medical history, behavioral risk factors, and environmental exposures. An identical, detailed questionnaire on the use of medications and vaccines was administered to all cases and controls. It spanned a 2-year time frame before the interview in accordance with PGRx methodology, although only data relating to the year before the index date were used in this study. The interviews of cases and controls were conducted within 45 days of recruitment by trained interviewers from the PGRx Patient Reported Outcomes Center. The telephone interviewer was blind to the case/control status of the interviewee. The interview was derived from methodology previously reported and covered 85 separate health conditions listed in a detailed interview guide given to the subjects ahead of the interview.21 The interview guide contained complete descriptions of medications and all vaccines marketed in France, their brand names, and corresponding images of packaging.

Vaccinations were included in the analysis if they were reported by the patient. The agreement between patients' reports of drug use and physicians' prescriptions has been described and published elsewhere.22,23

For some specific vaccinations that were studied for other purposes, confirmation of vaccination was sought. Confirmation of influenza vaccination was requested and obtained from either the patient or his/her GP, for a sample of 40% of cases and controls reporting this vaccination. Confirmation consisted of the vaccine batch number or a document confirming vaccination (eg, a prescription and a certificate from the physician).

This study analyzed exposure to all vaccines and to specific vaccines when used by at least 5% of controls in the 12-month time window. Other vaccines were reported by too few patients to be analyzed separately. For example, of the 878 controls included in the study, 10 (1.1%) reported a hepatitis B vaccination and 10 (1.1%) reported a pneumococcal vaccination. For the analysis of all vaccines in the 12 months before the index date, the minimum detectable odds ratio (OR) was 1.58 (based on 198 cases, 5 controls per case, 35% of the study population exposed, 80% power, and a 2-sided α error of 5%).

Assessment of exposure to other potential risk factors for ITP

Additional information collected during the telephone interview included sociodemographic factors, medications taken, and family history of autoimmune disorders. For each patient recruited, the nominated treating GP (for cases) or the recruiting GP (for controls) completed an electronic data form including prescriptions for the previous 2 years.

Time windows defining exposure to vaccines for ITP

Vaccine exposure was defined as a vaccine shot during one of the time windows defining exposure. Time windows were defined according to assumptions regarding the potential time to development of ITP after vaccination. Time windows of 12, 6, and 2 months before the index date were studied.

Statistical methods

Potential risk factors for ITP were identified as: history of autoimmune disorders in first-degree relatives (yes/no/unknown/missing) and use of systemic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in the 12 months before the index date (yes/no). These 2 factors have been shown to be associated with thrombocytopenia.24,25 We considered NSAIDs among all drugs that have been associated with ITP, as these were commonly used in the study population.

Cases and their matched controls were compared in respect of these potential risk factors using matched crude ORs. Cases and controls were also compared with respect to any vaccination, vaccination against influenza, and vaccination against DTPP in the 12, 6, and 2 months before the index date using crude and adjusted ORs. Adjusted ORs controlled for the potential risk factors for ITP listed in the preceding paragraph. Because vaccinations were considered as exposures for ITP in this study, the separate adjusted analyses of influenza and DTPP vaccines also controlled for vaccination with any vaccine other than influenza or DTPP (as applicable) in the 24 months before the index date.

ORs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using conditional logistic regression. Statistically significant associations were described for the 5% level. Analyses were performed with SAS Version 9.2 software (SAS Institute) by data managers listed in the Acknowledgments section. All authors had access to primary clinical data.

Results

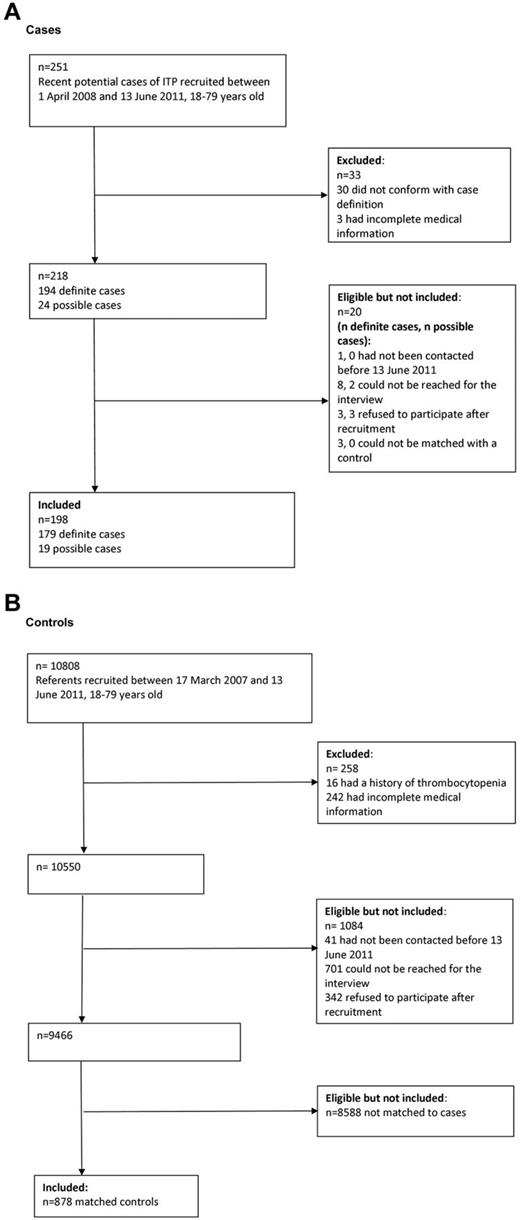

Among the 28 adult centers approached to participate in the PGRx-ITP registry, 22 (78.6%) agreed to participate and reported cases considered in this study. A total of 20 999 GPs were approached to participate in the PGRx-GP registry, 387 (1.8%) agreed to participate, and, of these, 216 (55.8%) recruited controls included in this study. The flow charts in Figure 1 describe the recruitment of cases and controls. A total of 198 newly diagnosed ITP cases were included in the study and were matched with 878 controls. Cases and controls were similar in terms of age (mean, 49.0 years, SD = 18.2 for both cases and controls), sex (119 [60.1%] of cases and 519 [59.1%] of controls were female) and region of residence.

Of the 198 ITP cases included, the majority presented with a platelet count at or below 50 G/L and at least one hemorrhagic symptom. Hemorrhagic symptoms were largely cutaneous and/or mucosal; only 8 cases (4.0%) suffered from a visceral hemorrhage. The first treatment most commonly administered was corticosteroids (159 [80.3%] of cases), followed by IV Ig (100 [50.5%]), and 164 (82.8%) of cases had at least a short-term response to initial treatment (Table 1).

Clinical features of cases (N = 198)

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 119 (60.1) |

| Male | 79 (39.9) |

| Ratio | 1.5 |

| Age at diagnosis, y | |

| Overall | |

| Mean (SD) | 49.0 (18.2) |

| Median | 50.8 |

| Female (n = 119) | |

| Mean (SD) | 45.4 (18.3) |

| Median | 42.7 |

| Male (n = 79) | |

| Mean (SD) | 54.4 (16.8) |

| Median | 57.3 |

| Platelet count at diagnosis, G/L | |

| Mean (SD) | 15.1 (17.1) |

| Median (min-max) | 7.5 (0.0-87.0) |

| At or below 50 G/L | 186 (94.4) |

| Bleeding symptoms at diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Epistaxis | 38 (19.2) |

| Cutaneous bleeding | 154 (77.8) |

| Bleeding from mucous membranes | 90 (45.5) |

| Visceral hemorrhage | 8 (4.0) |

| At least 1 bleeding symptom | 166 (83.8) |

| Days from first symptom to recruitment, mean (SD) | 73.3 (90.1) |

| Frontline treatment, n (%) | |

| Corticosteroids | 159 (80.3) |

| IV Ig | 100 (50.5) |

| Other treatment | 14 (7.1) |

| Overall initial response to treatment* | 164 (82.8) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 119 (60.1) |

| Male | 79 (39.9) |

| Ratio | 1.5 |

| Age at diagnosis, y | |

| Overall | |

| Mean (SD) | 49.0 (18.2) |

| Median | 50.8 |

| Female (n = 119) | |

| Mean (SD) | 45.4 (18.3) |

| Median | 42.7 |

| Male (n = 79) | |

| Mean (SD) | 54.4 (16.8) |

| Median | 57.3 |

| Platelet count at diagnosis, G/L | |

| Mean (SD) | 15.1 (17.1) |

| Median (min-max) | 7.5 (0.0-87.0) |

| At or below 50 G/L | 186 (94.4) |

| Bleeding symptoms at diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Epistaxis | 38 (19.2) |

| Cutaneous bleeding | 154 (77.8) |

| Bleeding from mucous membranes | 90 (45.5) |

| Visceral hemorrhage | 8 (4.0) |

| At least 1 bleeding symptom | 166 (83.8) |

| Days from first symptom to recruitment, mean (SD) | 73.3 (90.1) |

| Frontline treatment, n (%) | |

| Corticosteroids | 159 (80.3) |

| IV Ig | 100 (50.5) |

| Other treatment | 14 (7.1) |

| Overall initial response to treatment* | 164 (82.8) |

Response was defined by a platelet count above 30 × 109/L with at least a 2-fold increase from pretreatment count.

Table 2 shows that cases and controls were similar for the matching variables age, sex, region of residence, index date, and season of the index date. Neither family history of autoimmune disorders nor systemic NSAIDs in the 12 months before the index date showed any statistically significant associations with case/control status in crude analyses.

Description of cases and matched controls

| . | Cases (n = 198) . | Controls (n = 878) . | Crude ORs (95% CI) . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matching factor* | ||||

| Age, y | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 49.0 (18.2) | 49.0 (18.2) | NA | |

| Median | 50.8 | 51.2 | ||

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 119 (60.1) | 519 (59.1) | NA | |

| Male | 79 (39.9) | 359 (40.9) | ||

| Region of residence, n (%) | ||||

| Northern France | 90 (45.5) | 397 (45.2) | NA | |

| Southern France | 108 (54.5) | 481 (54.8) | ||

| Season of index date, n (%) | ||||

| Spring/summer | 119 (60.1) | 537 (61.1) | NA | |

| Fall/winter | 79 (39.9) | 341 (38.8) | ||

| Potential risk factors for ITP, n (%) | ||||

| Family history of autoimmune disorders† | ||||

| Yes | 16 (8.1) | 66 (7.5) | 1.0 (0.6-1.8) | |

| Unknown or missing | 44 (22.2) | 229 (26.1) | 0.6 (0.3-1.1) | |

| No | 138 (69.7) | 583 (66.4) | 1 | |

| Systemic NSAID(s) intake in the 12 mo before the index date | ||||

| Yes | 113 (57.1) | 498 (56.7) | 1.0 (0.7-1.4) | |

| No | 85 (42.9) | 380 (43.3) | 1 | |

| . | Cases (n = 198) . | Controls (n = 878) . | Crude ORs (95% CI) . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matching factor* | ||||

| Age, y | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 49.0 (18.2) | 49.0 (18.2) | NA | |

| Median | 50.8 | 51.2 | ||

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 119 (60.1) | 519 (59.1) | NA | |

| Male | 79 (39.9) | 359 (40.9) | ||

| Region of residence, n (%) | ||||

| Northern France | 90 (45.5) | 397 (45.2) | NA | |

| Southern France | 108 (54.5) | 481 (54.8) | ||

| Season of index date, n (%) | ||||

| Spring/summer | 119 (60.1) | 537 (61.1) | NA | |

| Fall/winter | 79 (39.9) | 341 (38.8) | ||

| Potential risk factors for ITP, n (%) | ||||

| Family history of autoimmune disorders† | ||||

| Yes | 16 (8.1) | 66 (7.5) | 1.0 (0.6-1.8) | |

| Unknown or missing | 44 (22.2) | 229 (26.1) | 0.6 (0.3-1.1) | |

| No | 138 (69.7) | 583 (66.4) | 1 | |

| Systemic NSAID(s) intake in the 12 mo before the index date | ||||

| Yes | 113 (57.1) | 498 (56.7) | 1.0 (0.7-1.4) | |

| No | 85 (42.9) | 380 (43.3) | 1 | |

NA indicates not applicable.

Cases and controls were also matched by index date (± 2 mo).

Family history of autoimmune disorders included the following in first-degree relatives: multiple sclerosis, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, and autoimmune thyroiditis. These data were only available for patients interviewed after September 11, 2008.

Overall, 66 cases (33.3%) and 303 controls (34.5%) received a vaccination within 12 months before the index date. Cases and controls were similar in terms of the proportions vaccinated in the 12 months (adjusted OR = 1.0; 95% CI, 0.7-1.4), 6 months (adjusted OR = 1.1; 95% CI, 0.7-1.7), and 2 months (adjusted OR = 1.3; 95% CI, 0.7-2.3) before the index date. For vaccination against influenza, the adjusted ORs were 0.7 (95% CI, 0.5-1.1) in the 12 months before the index date, 0.9 (95% CI, 0.6-1.6) in the 6 months before, and 0.9 (95% CI, 0.4-2.1) in the 2 months before. For vaccination against DTPP, the adjusted ORs were 1.4 (95% CI, 0.8-2.4) in the 12 months before the index date, 1.3 (95% CI, 0.6-2.7) in the 6 months before, and 1.5 (95% CI, 0.5-4.5) in the 2 months before the index date (Table 3).

Comparison of cases and controls in terms of exposure to vaccination

| Exposure and time window before the index date . | Cases (n = 198) . | Controls (n = 878) . | Crude ORs (95% CI) . | Adjusted ORs (95% CI)† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any vaccine, n (%) | ||||

| 12 mo | 66 (33.3) | 303 (34.5) | 1.0 (0.7-1.4) | 1.0 (0.7, 1.4) |

| Without dates of vaccination | 5 (2.5) | 24 (2.7) | 1.0 (0.4-2.7) | 1.0 (0.4, 2.8) |

| No exposure | 127 (64.1) | 551 (62.8) | 1 | 1 |

| 6 mo | 42 (21.2) | 177 (20.2) | 1.1 (0.7-1.7) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.7) |

| Without dates of vaccination | 6 (3.0) | 24 (2.7) | 1.2 (0.5-3.2) | 1.3 (0.5, 3.2) |

| No exposure | 150 (75.8) | 677 (77.1) | 1 | 1 |

| 2 mo | 17 (8.6) | 62 (7.1) | 1.3 (0.7-2.4) | 1.3 (0.7, 2.3) |

| Without dates of vaccination* | 6 (3.0) | 24 (2.7) | ||

| No exposure | 175 (88.4) | 792 (90.2) | 1 | 1 |

| Influenza vaccine, n (%) | ||||

| 12 mo | 43 (21.7) | 242 (27.6) | 0.7 (0.5-1.1) | 0.7 (0.5-1.1)‡ |

| Without dates of vaccination | 1 (0.5) | 9 (1.0) | 0.5 (0.1-4.1) | 0.5 (0.1-4.4)‡ |

| No exposure | 154 (77.8) | 627 (71.4) | 1 | 1 |

| 6 mo | 28 (14.1) | 133 (15.1) | 0.9 (0.6-1.6) | 0.9 (0.6-1.6)‡ |

| Without dates of vaccination | 2 (1.0) | 9 (1.0) | 1.1 (0.2-5.2) | 1.2 (0.3-6.0)‡ |

| No exposure | 168 (84.8) | 736 (83.8) | 1 | 1 |

| 2 mo | 9 (4.5) | 43 (4.9) | 1.0 (0.4-2.1) | 0.9 (0.4-2.1) |

| Without dates of vaccination* | 2 (1.0) | 9 (1.0) | ||

| No exposure | 187 (94.4) | 826 (94.1) | 1 | 1 |

| DTPP vaccine, n (%) | ||||

| 12 mo | 18 (9.1) | 62 (7.1) | 1.3 (0.8-2.3) | 1.4 (0.8-2.4)§ |

| Without dates of vaccination | 3 (1.5) | 13 (1.5) | 1.2 (0.3-4.1) | 1.1 (0.3-4.1)§ |

| No exposure | 177 (89.4) | 803 (91.5) | 1 | 1 |

| 6 mo | 10 (5.1) | 34 (3.9) | 1.3 (0.6-2.7) | 1.3 (0.6-2.7)§ |

| Without dates of vaccination | 3 (1.5) | 13 (1.5) | 1.2 (0.3-4.1) | 1.1 (0.3-4.0)§ |

| No exposure | 185 (93.4) | 831 (94.6) | 1 | 1 |

| 2 mo | 4 (2.0)* | 13 (1.5)* | 1.5 (0.5-4.6) | 1.5 (0.5-4.5) |

| Without dates of vaccination* | 3 (1.5) | 13 (1.5) | ||

| No exposure | 191 (96.5) | 852 (97.0) | ||

| Exposure and time window before the index date . | Cases (n = 198) . | Controls (n = 878) . | Crude ORs (95% CI) . | Adjusted ORs (95% CI)† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any vaccine, n (%) | ||||

| 12 mo | 66 (33.3) | 303 (34.5) | 1.0 (0.7-1.4) | 1.0 (0.7, 1.4) |

| Without dates of vaccination | 5 (2.5) | 24 (2.7) | 1.0 (0.4-2.7) | 1.0 (0.4, 2.8) |

| No exposure | 127 (64.1) | 551 (62.8) | 1 | 1 |

| 6 mo | 42 (21.2) | 177 (20.2) | 1.1 (0.7-1.7) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.7) |

| Without dates of vaccination | 6 (3.0) | 24 (2.7) | 1.2 (0.5-3.2) | 1.3 (0.5, 3.2) |

| No exposure | 150 (75.8) | 677 (77.1) | 1 | 1 |

| 2 mo | 17 (8.6) | 62 (7.1) | 1.3 (0.7-2.4) | 1.3 (0.7, 2.3) |

| Without dates of vaccination* | 6 (3.0) | 24 (2.7) | ||

| No exposure | 175 (88.4) | 792 (90.2) | 1 | 1 |

| Influenza vaccine, n (%) | ||||

| 12 mo | 43 (21.7) | 242 (27.6) | 0.7 (0.5-1.1) | 0.7 (0.5-1.1)‡ |

| Without dates of vaccination | 1 (0.5) | 9 (1.0) | 0.5 (0.1-4.1) | 0.5 (0.1-4.4)‡ |

| No exposure | 154 (77.8) | 627 (71.4) | 1 | 1 |

| 6 mo | 28 (14.1) | 133 (15.1) | 0.9 (0.6-1.6) | 0.9 (0.6-1.6)‡ |

| Without dates of vaccination | 2 (1.0) | 9 (1.0) | 1.1 (0.2-5.2) | 1.2 (0.3-6.0)‡ |

| No exposure | 168 (84.8) | 736 (83.8) | 1 | 1 |

| 2 mo | 9 (4.5) | 43 (4.9) | 1.0 (0.4-2.1) | 0.9 (0.4-2.1) |

| Without dates of vaccination* | 2 (1.0) | 9 (1.0) | ||

| No exposure | 187 (94.4) | 826 (94.1) | 1 | 1 |

| DTPP vaccine, n (%) | ||||

| 12 mo | 18 (9.1) | 62 (7.1) | 1.3 (0.8-2.3) | 1.4 (0.8-2.4)§ |

| Without dates of vaccination | 3 (1.5) | 13 (1.5) | 1.2 (0.3-4.1) | 1.1 (0.3-4.1)§ |

| No exposure | 177 (89.4) | 803 (91.5) | 1 | 1 |

| 6 mo | 10 (5.1) | 34 (3.9) | 1.3 (0.6-2.7) | 1.3 (0.6-2.7)§ |

| Without dates of vaccination | 3 (1.5) | 13 (1.5) | 1.2 (0.3-4.1) | 1.1 (0.3-4.0)§ |

| No exposure | 185 (93.4) | 831 (94.6) | 1 | 1 |

| 2 mo | 4 (2.0)* | 13 (1.5)* | 1.5 (0.5-4.6) | 1.5 (0.5-4.5) |

| Without dates of vaccination* | 3 (1.5) | 13 (1.5) | ||

| No exposure | 191 (96.5) | 852 (97.0) | ||

The numbers exposed were too small to calculate meaningful ORs.

ORs were adjusted for: family history of autoimmune disorders (yes/no/unknown/missing) and systemic NSAID(s) in the 12 mo before the index date (yes/no).

ORs were also adjusted for vaccination with any vaccine other than influenza in the 24 mo before the index date (yes/no).

ORs were also adjusted for vaccination with any vaccine other than DTPP in the 24 mo before the index date (yes/no).

Discussion

We report a prospective multicenter case-control study designed to address a potential association between adult ITP and different routinely administered vaccines. We found no evidence that vaccination in general was associated with an observable increase in the incidence of ITP. Similar proportions of cases and controls had been exposed to vaccination in the 12 and 6 months before the index date. When the 2-month time window was used, higher ORs were observed for all vaccines (OR = 1.3) mainly attributable to the vaccination against DTPP (OR = 1.5). However, this increase was not statistically significant. The magnitude of the 95% CIs for the individual vaccines showed that the study lacked power to conclude on them and particularly for DTPP. The minimum detectable OR for the 12-month time window was 1.58 and the study could not rule out weaker associations. Applying a formal test of equivalence to our data would not have yielded a conclusion of equivalence if narrow OR equivalence ranges such as 0.75-1.33 or narrower had been considered.

Advantages of this study include the prospective recruitment of incident cases of ITP, the availability of a general practice-based referent population, and the standardized and validated methods for the collection of cases, controls, and data. Because ITP is a rare disease, large-scale studies of ITP patients such as this one are few. Between April 1, 2008 and June 13, 2011, 198 cases were recruited by 22 specialist centers across France. ITP was diagnosed according to strict criteria and cases with a previous history of thrombocytopenia were excluded. This ensured that, as far as possible, relationships between vaccinations and ITP were described for incident cases. Specialist centers recruiting cases and general practice settings recruiting referents were widespread throughout France, so the study population was likely to be generalizable to the French population. Referents were found to be representative of French patients presenting to GPs in terms of their reasons for consultation (comparison with national data,26 results not shown). In addition, all methods for the collection of cases, controls, and data were standardized and validated to reduce the potential for bias.22,23

The greater exposure to influenza vaccines in the time window of 12 months preceding the index date in the control group was unexpected and raises the question about a possible protective effect of the vaccine. Several infections have been associated with ITP, including Helicobacter pylori, hepatitis C virus, and HIV.6 Childhood ITP is often preceded by infectious prodromes, suggesting a viral infection,27 whereas in adults, only a few case reports of seasonal relapse of ITP caused by influenza A virus infection have been reported.28

A passive safety surveillance system for pandemic (H1N1) 2009 vaccines conducted in Taiwan and based on a capture-recapture analysis did not support an increased risk of ITP.29 In contrast, a case-control study recently reported a potential association between adult ITP and influenza vaccine.30 The investigators reported 3 cases of possible ITP related to influenza vaccine among a group of 169 adults with newly diagnosed ITP. They concluded that this vaccine was associated with a 4-fold increase in the risk of ITP. However, data regarding the exposure to vaccines were lacking in both the ITP group and in the controls. Moreover, neither the ITP patients' nor the controls' selection criteria were comparable to the ones used in our study. Inpatient controls, for example, were selected among patients admitted to departments of surgery without mentioning their length of stay in the hospital.

A few case reports have described clusters of ITP incidence within families.24,31,32 We found a similar prevalence of family history of autoimmune disorders between ITP cases and controls, suggesting that it is not a predisposing factor for ITP. Although a history of multiple sclerosis or Guillain Barré syndrome is considered by some to be contraindication for various vaccines,33 based on the results found in the present study, a family history of autoimmune disorders is not a risk factor for ITP after immunization in adults.

Our sample size was not sufficient to test the possible association between vaccines against specific antigens rarely used in the general population and ITP. In addition, the number of cases did not permit the analysis of effects in different age groups such as younger adults (only 21 cases and 95 controls were 18-24 years of age). Moreover, our study did not consider the risk associated with immunization in patients with known ITP.

The clinical features of ITP cases at diagnosis were consistent with those described previously, which suggests that there was no bias in the selection of patients. In a retrospective case-series study, Frederiksen et al evaluated 221 adults diagnosed with ITP (platelet count < 100 G/L) between April 1973 and December 1995, inclusive, in the county of Funen in Denmark.4 In keeping with Frederiksen et al, we observed in the present study that ITP affected a wide age range of subjects, that the incidence peaked in middle age (a median of 50.8 years in our study and 56 years in the Danish study), and that the female to male ratio was 1.5 (1.7 in the Danish study).4 We also observed that visceral hemorrhages were fairly rare (4.0%).

To conclude, the results of the present study show that in an adult population, the exposure to common vaccines is on average not associated with an observable risk of developing ITP. Further studies should now address whether some vaccines may induce a relapse or worsen the course of the disease in patients previously diagnosed with ITP, as has already been investigated for rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus.34-37

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

Yann Hamon and Benoît David (data managers/statisticians employed by LA-SER) performed the SAS programming for this study. The following people participated in the recruitment of patients: Guy Barberet (Belfort, France); Jean-Francois Baron (Chatellerault, France); Jean-Louis Bensoussan (Castelmaurou, France); Christian Bourel (Pace, France); Laurent Bremond (Pornic, France); Alain Brousse (Le Mas d'Agenais, France); Claude Burguier (Toulouse, France); Paul Chiri (Marseille, France); Samuel Cohen (Miramas, France); Isabelle Cornette (Saint Pierre-Des-Corps, France); Thierry Coulis (Les Ponts De Ce, France); Daniele Delbecque (Tourcoing, France); Dominique Delsart (Dersee, France); Michel Delvallez (Thun-Saint-Amand, France); Philippe Ducamp (Narrosse, France); Emmanuelle Honnart (Petite Foret, France); Pierre Llory (Poussan, France); Gilbert Ohayon (Ablon-Sur-Seine, France); Jacqueline Plot (Paris, France); Christiane Philoctete (Toulouse, France); Wilfrid Planchamp (Ambilly, France); Jean-Marc Ponzio (Nimes, France); Philippe Regnault (Montbazon, France); Jean Salvaggio (Rombas, France); Bernard Steinberg (Vergeze, France); Pierre Tran (Meudon-La-Foret, France); Philippe Trehou (Guise, France); Philippe Uge (Bordeaux, France); Patrick Vandevyvere (Pont Aven, France); and Reine Viallat (Saint Etienne, France).

Authorship

Contribution: L.G.-B. and L.A. designed and supervised the study, wrote the protocol and statistical analysis plan, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; M.M. defined the study (cases) inclusion criteria, recruited the patients, and interpreted the data; E.A. supervised the study, centers, and data and wrote the protocol; P.L. performed the literature review, analyzed the data, and wrote and edited the manuscript; B.G. designed the study, recruited the patients, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; and the other authors recruited the patients, analyzed the data, and reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.-F.V., M.K., O.F., and M.M. have participated in advisory boards and symposia for Amgen and Glaxo SmithKline (honoraria of less than 10 000 USD). M.M. is a member of the PGRx expert panel and is the main coordinator for ITP studies. M.K. and M.M. have also received research funding from Roche. M.R. has participated as an investigator in observational studies sponsored by Roche and by UCB (honoraria of less than 5000 USD). B.G. is a member of the PGRx expert panel, has participated in advisory boards and symposia for Amgen, Roche, Sanofi-Pasteur MSD, LFB, and Glaxo SmithKline (honoraria of less than 10 000 USD), and has received research funding from Roche. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

A complete list of the members of the PGRx-ITP study group appears in the supplemental Appendix (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Correspondence: Lamiae Grimaldi-Bensouda, LA-SER, 10 Place de Catalogne, 75014 Paris, France; e-mail: lamiae.grimaldi@la-ser.com.