Abstract

Epidemiologic studies suggest that elevated VWF levels and reduced ADAMTS13 activity in the plasma are risk factors for myocardial infarction. However, it remains unknown whether the ADAMTS13-VWF axis plays a causal role in the pathophysiology of myocardial infarction. In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that ADAMTS13 reduces VWF-mediated acute myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury in mice. Infarct size, neutrophil infiltration, and myocyte apoptosis in the left ventricular area were quantified after 30 minutes of ischemia and 23.5 hours of reperfusion injury. Adamts13−/− mice exhibited significantly larger infarcts concordant with increased neutrophil infiltration and myocyte apoptosis compared with wild-type (WT) mice. In contrast, Vwf−/− mice exhibited significantly reduced infarct size, neutrophil infiltration, and myocyte apoptosis compared with WT mice, suggesting a detrimental role for VWF in myocardial I/R injury. Treating WT or Adamts13−/− mice with neutralizing Abs to VWF significantly reduced infarct size compared with control Ig–treated mice. Finally, myocardial I/R injury in Adamts13−/−/Vwf−/− mice was similar to that in Vwf−/− mice, suggesting that the exacerbated myocardial I/R injury observed in the setting of ADAMTS13 deficiency is VWF dependent. These findings reveal that ADAMTS13 and VWF are causally involved in myocardial I/R injury.

Introduction

ADAMTS13 (a disintegrin and metalloprotease with thrombospondin type I repeats-13) is a plasma protease that is synthesized primarily by hepatic stellate cells1,2 and to a lesser extent by endothelial cells3 and megakaryocytes.4 The only known substrate for ADAMTS13 is VWF, a multimeric glycoprotein that plays a key role in hemostasis and thrombosis by stabilizing factor VIII and initiating platelet adhesion and aggregation at sites of vascular injury.5 VWF is stored as ultra-large VWF (ULVWF) multimers in platelet α-granules and endothelial storage granules called Weibel-Palade bodies. ULVWF multimers are considered hyperactive because they bind avidly to the extracellular matrix6 and form high-strength bonds with platelet glycoprotein Ibα (GPIbα).7 ULVWF multimers are not present in the plasma of healthy humans; however, on endothelial cell activation or injury, they are released into the circulation from Weibel-Palade bodies. During the process of secretion, ULVWF multimers remain transiently bound to the endothelial surface, where they are cleaved by ADAMTS13 into smaller and less active VWF multimers.8 Clinically, deficiency of VWF causes VWD, the most common bleeding disorder in humans.9 Conversely, deficiency of ADAMTS13 results in accumulation of ULVWF multimers in the plasma and causes thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, a disorder of thrombotic microangiopathy.10

Cardiovascular diseases, including myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke, are major causes of mortality and disability worldwide and are a major contributor to rising health care costs. Several case-control studies have found that elevated VWF levels and reduced ADAMTS13 Ag levels in the plasma are associated with a high risk of myocardial infarction.11-16 However, it remains unknown whether the ADAMTS13-VWF axis plays a causal role in the pathophysiology of acute myocardial infarction or is an associative marker of the disease status. We hypothesized that ADAMTS13 may protect from myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury because: (1) ADAMTS13 deficiency in mice results in increased VWF-dependent vascular inflammation17-19 and (2) it was demonstrated recently that ADAMTS13 deficiency exacerbates I/R brain injury in a murine model,20,21 whereas VWF deficiency had the opposite effect.21-23 Moreover, we and others have shown recently that ADAMTS13 deficiency promotes inflammation after I/R brain injury and that acute inflammatory brain injury in Adamts13−/− mice is VWF dependent.24,25

In the present study, we used mice deficient in ADAMTS13 (Adamts13−/−), VWF (Vwf−/−), or both ADAMTS13 and VWF (Adamts13−/−/Vwf−/−) to investigate the role of ADAMTS13 and its substrate VWF in myocardial I/R injury. Our findings reveal a critical role for ADAMTS13 in reducing VWF-mediated acute myocardial I/R injury.

Methods

Animals

Adamts13−/−,26 Vwf−/−,27 and Adamts13−/−/Vwf−/−28 mice backcrossed > 15 times to C57BL/6 mice were used for the experiments. Control mice were heterozygous littermates or age-matched wild-type (WT) C57BL/6J mice (The Jackson Laboratory). All mice used were males between 8 and 10 weeks of age. All experiments were approved by the University of Iowa Animal Care and Use Committee.

Myocardial I/R injury model

We used a well-established left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery ligation model, as described previously.29 The mouse was anesthetized with 0.10 mL/20 g body weight of a cocktail consisting of ketamine (87.5 mg/kg body weight) and xylazine (2.5 mg/kg body weight). The anesthetized mouse was placed in a supine position with its paws taped on a Plexiglas board before endotracheal intubation and ventilation using a mini-ventilator (Harvard Apparatus). Body temperature was maintained at 37°C ± 1.0 using a heating pad. The ventilator was set to a stroke volume of 250 μL and 125 strokes per minute. Surgery was performed using an Olympus dissecting microscope. The left pectoralis major muscles were refracted toward the right shoulder and the left rectus thoracis and serratus anterior muscles were refracted toward the left shoulder with microretractors. Thoracotomy was performed in the intercostal space between fourth and fifth ribs, and self-retaining microretractors were used to expose the operating region while preserving rib integrity. A sterile polyamide monofilament (8-0) suture was passed under the LAD coronary artery 2 mm distal to the left atrial appendage immediately inferior to the bifurcation of major left coronary artery. For induction of ischemia, a short segment of PE-10 tubing was placed between the LAD coronary artery and suture to protect the artery against traumatic injury and the vessel was ligated. Mice were subjected to 30 minutes of ischemia, which was confirmed by blanching of the left ventricle. At the end of the ischemic period, the LAD coronary artery ligation was removed and reperfusion was confirmed by visual inspection of the left ventricle. The chest was closed with running sutures (one muscle suture layer and one skin suture layer) with sterile silk (6-0) suture. The mouse was gently removed from the ventilator and placed on a heating pad and monitored until fully recovered from anesthesia. Then, 300 μL of normal saline was injected intraperitoneally at the end of surgical procedure. In sham-operated animals, the procedure was done identically except that the suture was passed under the LAD coronary artery but not tied. Before euthanasia (23.5 hours after reperfusion), heparinized blood samples were collected for measuring plasma cardiac troponin T (TnT) levels. For morphometric measurement, 2-mm serial sections were cut using a mouse Heart Matrix (Roboz Surgical Instrument). Sections were stained with 2% triphenyl-2,3,4-tetrazolium-chloride for 15 minutes at 37°C. Sections were scanned on both sides, digitalized, and infarct areas on each side measured using ImageJ software (Olympus-BX51/DP-72). The mean infarcted area was calculated as a percentage of the left ventricular area.

TnT levels

Plasma cardiac TnT levels were measured with commercially available quantitative sandwich ELISA kit (Roche-Cobas) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Determination of VWF levels in Vwf−/− mice infused with plasma from WT mice

150 μL citrated (3.8%) WT plasma was infused intravenously (retroorbitally) in Vwf−/− mice before surgery. Similarly, 150 μL of citrated (3.8%) Adamts13−/− plasma was infused intravenously (retroorbitally) in Adamts13−/−/Vwf−/− mice before surgery. In a separate set of experiments, blood samples were collected from Vwf−/− mice at 1, 4, and 24 hours after infusion of citrated WT plasma (150 μL). Plasma VWF levels were quantified by ELISA, as described previously.30 Briefly, plasma VWF was detected with rabbit anti-VWF A0082 (Dako) as primary Ab and HRP-conjugated anti-VWF (Dako) as a secondary Ab. 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate solution (Sigma-Aldrich) was used for detection. Normal pooled plasma obtained from 3 WT mice was used to generate a standard curve.

Endogenous VWF inhibition

WT and Adamts13−/− mice subjected to the myocardial I/R injury model were gently removed from the ventilator after surgery and placed on a heating pad. Ten minutes after surgery (approximately 23 hours before euthanasia), rabbit anti-VWF Abs (6 μg/g body weight, clone A0082; Dako) or control Ig (rabbit Ig fraction X0903; Dako) were infused intravenously. VWF inhibition was confirmed by measuring tail-bleeding time in WT and Adamts13−/− mice before euthanizing mice for quantification of the infarct size.

Bleeding time

Mice were anesthetized with 2.5% Avertin (15 μL/g mouse body weight IP) and a 2-mm segment of tail was amputated. Body temperature was maintained at 37°C ± 1.0 using a heating pad. The tail was immersed in PBS at 37°C and the time required for the stream of blood to stop for more than 30 seconds was defined as the bleeding time.

Immunohistochemical analysis

Immunostaining of neutrophils was done 23.5 hours after reperfusion injury on perfused heart via an intracardiac delivery of 30 mL of PBS containing 0.05M EDTA (pH 7.4), followed by 30 mL of 4% formalin. The hearts were fixed for 24 hours in 4% paraformaldehyde and paraffin embedded. Then, 5.0-μm sections were cut and incubated with blocking reagent followed by primary Ab (rat anti–mouse Ly6B.2 (1:100; AbD Serotec) or rat Ig (control) in the presence of 5% rabbit serum overnight at 4°C, followed by biotin-conjugated rabbit anti–rat Ig, avidin-linked HRP complex, and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine as substrate. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and examined under a light microscope (Olympus). Extravascular neutrophils were quantified by counting the immunoreactive cells with ImageJ software (with the plugin for individual cell analysis) in 4 different regions of the infarcted and surrounding regions at a 200× magnification. Four fields in 4 serial sections (separated by 30 μm) per mouse were counted for immunoreactive cells. Each mouse represents a mean of 16 fields from 4 serial sections.

Myocyte apoptosis

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl-transferase mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining was performed 23.5 hours after reperfusion injury on perfused hearts. Briefly, hearts were fixed for 24 hours in 4% paraformaldehyde and paraffin embedded. Then, 5.0-μm-thick sections were cut and treated with an in situ cell death detection kit (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's instruction. The TUNEL signal was then detected by an anti-fluorescein Ab conjugated with alkaline phosphatase, which generates a red-colored product with the Vector Red Substrate Kit (Vector Laboratories). Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and examined under a light microscope (Olympus). Apoptotic cells were quantified by ImageJ software (with the plugin for individual cell analysis) in 4 predetermined regions of the infracted region at a 200× magnification. The apoptotic cells were counted using the following formula: (number of TUNEL positive cell nuclei/ number of total cell nuclei) ×100. Four random fields in 4 serial sections (separated by 30 μm) per mouse were counted for the percentage of apoptotic nuclei. Each mouse represents a mean of 16 fields from 4 serial sections.

Statistics

Results are reported as means ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were performed using ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni multiple comparison test. Ab treatment and genotype effects were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak multiple comparison tests. P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

ADAMTS13 deficiency exacerbates acute myocardial I/R injury

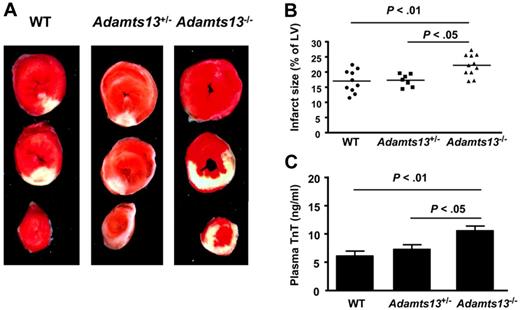

To investigate the role of ADAMTS13 in acute myocardial I/R injury, we compared infarct size in WT, Adamts13−/−, and Adamts13+/− mice after 30 minutes of ischemia and 23.5 hours of reperfusion. Adamts13−/− mice exhibited significantly increased infarct size (22.2% ± 1.1%; P < .01) compared with WT mice (16.9% ± 1.2%; Figure 1A-B). Plasma cardiac TnT level, an index of myocyte injury, was significantly higher in Adamts13−/− mice compared with WT mice (P < .01; Figure 1C). In the Adamts13+/− mice, the infarct size (17.3% ± 0.8%) and plasma cardiac TnT levels were similar to those in WT mice, but were significantly reduced compared with those in Adamts13−/− mice (P < .05; Figure 1A-C). TnT levels were significantly lower in WT sham-operated animals (0.7 ± 0.1 ng/mL) compared with WT animals that underwent myocardial I/R injury (6.1 ± 0.9 ng/mL; P < .0001); however, TnT levels were similar between sham-operated WT (0.7 ± 0.1 ng/mL) and sham-operated Adamts13−/− mice (0.6 ± 0.2 ng/mL; P = .56; n = 4/group). These findings demonstrate that complete ADAMTS13 deficiency exacerbates myocardial I/R injury, whereas heterozygous deficiency does not, which suggests that approximately 50% ADAMTS13 levels in plasma are sufficient to prevent aggravated myocardial I/R injury.

ADAMTS13 deficiency promotes acute myocardial I/R injury. (A) Representative triphenyl-2,3,4-tetrazolium-chloride–stained heart sections from one mouse of each genotype after 30 minutes of ischemia and 23.5 hours of reperfusion injury. The infarcted area is white. (B) Quantification of the infarct size (n = 7-10/group). Each dot represents a single mouse. Horizontal bars indicate mean values. (C) Plasma cardiac TnT levels (n = 7-10 /group). Data are means ± SEM.

ADAMTS13 deficiency promotes acute myocardial I/R injury. (A) Representative triphenyl-2,3,4-tetrazolium-chloride–stained heart sections from one mouse of each genotype after 30 minutes of ischemia and 23.5 hours of reperfusion injury. The infarcted area is white. (B) Quantification of the infarct size (n = 7-10/group). Each dot represents a single mouse. Horizontal bars indicate mean values. (C) Plasma cardiac TnT levels (n = 7-10 /group). Data are means ± SEM.

VWF deficiency reduces acute myocardial I/R injury and ADAMTS13 deficiency–mediated aggravated myocardial I/R injury is VWF dependent

The role of VWF in promoting myocardial I/R injury has not been investigated previously, presumably because of technical limitations caused by severe bleeding in Vwf−/− mice during the surgical procedure. To overcome this problem, before the surgical procedure, we infused 150 μL of citrated WT plasma into Vwf−/− mice, thereby maintaining low VWF levels (10% compared with WT mice) during the first few hours of the surgical procedure (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). At 4 hours, the level of VWF in Vwf−/− mice was approximately 1.2% (supplemental Figure 1). The levels of VWF observed in the infused mice are consistent with the results of a previous published study showing that the half-life of biotinylated VWF in mice was approximately 2 hours.31 Using this strategy, 100% of the Vwf−/− mice survived the surgical procedure while maintaining severe VWF deficiency.

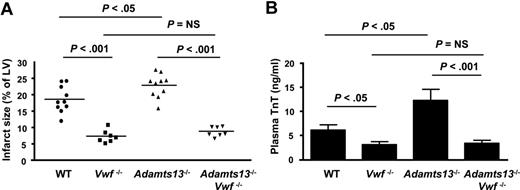

We found that Vwf−/− mice had marked (2.5-fold) reductions in infarct size (7.3% ± 0.7%) compared with WT mice (18.6% ± 1.3%; P < .001; Figure 2A). Plasma cardiac TnT levels also were significantly reduced in Vwf−/− mice compared with WT mice (P < .05; Figure 2B). We also investigated whether the effects of ADAMTS13 deficiency on infarct size observed in Adamts13−/− mice after myocardial I/R injury are dependent on VWF. To prevent surgical bleeding, Adamts13−/−/Vwf−/− mice were infused with 150 μL of citrated Adamts13−/− plasma before the procedure. Interestingly, infarct size (8.7% ± 0.6%) and plasma cardiac TnT levels in Adamts13−/−/Vwf−/− mice were similar to that in Vwf−/− mice (P = .14; Figure 2A-B). These results suggest that VWF promotes myocardial I/R injury and that this effect is modulated by ADAMTS13.

VWF deficiency reduces acute myocardial I/R injury and ADAMTS13 deficiency–mediated aggravated myocardial I/R injury is VWF dependent. (A) Quantification of the infarct size (n = 7-10/group). WT and Adamts13−/− mice are a different set of mice from those shown in Figure 1. Each dot represents a single mouse. Horizontal bars indicate mean values. (B) Plasma cardiac TnT levels (n = 7-10/group). Data are means ± SEM. NS indicates nonsignificant.

VWF deficiency reduces acute myocardial I/R injury and ADAMTS13 deficiency–mediated aggravated myocardial I/R injury is VWF dependent. (A) Quantification of the infarct size (n = 7-10/group). WT and Adamts13−/− mice are a different set of mice from those shown in Figure 1. Each dot represents a single mouse. Horizontal bars indicate mean values. (B) Plasma cardiac TnT levels (n = 7-10/group). Data are means ± SEM. NS indicates nonsignificant.

Neutralization of endogenous VWF protects WT and Adamts13−/− mice from exacerbated myocardial infarction injury.

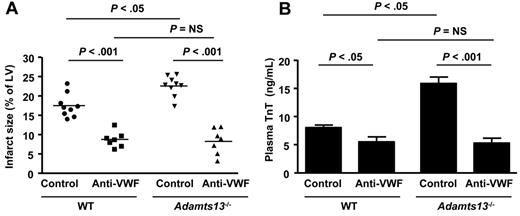

VWF-deficient mice have a defect in regulation of endothelial P-selectin because of the loss of Weibel-Palade body formation.32 To confirm that exacerbated myocardial I/R injury in the setting of ADAMTS13 deficiency is dependent on VWF rather than P-selectin, we compared WT and Adamts13−/− mice treated with anti-VWF inhibitory Abs. We used commercially available polyclonal anti-VWF Abs, which have been shown previously to inhibit VWF function in vivo.33 Anti-VWF Ig–treated WT mice showed a 2-fold reduction in infarct size (8.5% ± 0.7%) compared with control Ig-treated WT mice (17.48% ± 0.7%; P < .001; Figure 3A). Plasma cardiac TnT levels were also significantly reduced in anti-VWF Ig–treated WT mice compared with control Ig-treated WT mice (P < .05; Figure 3B). Interestingly, neutralizing VWF in Adamts13−/− mice resulted in an even more robust reduction in infarct size (8.2% ± 1.3%) compared with control Ig-treated Adamts13−/− mice (22.5% ± 0.8%; P < .05; Figure 3B). Plasma cardiac TnT levels were also significantly reduced in anti-VWF Ig-treated Adamts13−/− mice compared with control Ig–treated Adamts13−/− mice (P < .001; Figure 3A-B). Infarct size in anti–VWF Ig-treated WT mice (8.5% ± 0.7%) was similar to that in anti-VWF Ig-treated Adamts13−/− mice (8.2% ± 1.3%; P = .77). Two-way ANOVA showed that the interaction of genotype and treatment with the VWF inhibitor was significant (P = .01; F = 6.56). To determine whether the inhibition of VWF by anti-VWF Abs persisted until the 24-hour time point, we measured tail-bleeding time in WT and Adamts13−/− mice after 23.5 hours of reperfusion. Anti-VWF Ig–treated WT or Adamts13−/− mice had significantly prolonged bleeding times compared with control Ig-treated WT or Adamts13−/− mice (supplemental Figure 2). These findings demonstrate that the exacerbated myocardial I/R injury observed in Adamts13−/− mice is entirely VWF dependent.

VWF neutralization by anti-VWF Abs reduces myocardial I/R injury in WT and Adamts13−/− mice. (A) Quantification of the infarct size (n = 7-9/group). Each dot represents a single mouse. Horizontal bars indicate mean values. (B) Plasma cardiac TnT levels (n = 7-9/group). Data are means ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA showed that the interaction of genotype and treatment with the VWF inhibitor was significant (P = .017; F = 6.56). NS indicates nonsignificant.

VWF neutralization by anti-VWF Abs reduces myocardial I/R injury in WT and Adamts13−/− mice. (A) Quantification of the infarct size (n = 7-9/group). Each dot represents a single mouse. Horizontal bars indicate mean values. (B) Plasma cardiac TnT levels (n = 7-9/group). Data are means ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA showed that the interaction of genotype and treatment with the VWF inhibitor was significant (P = .017; F = 6.56). NS indicates nonsignificant.

Increased neutrophil infiltration associated with ADAMTS13 deficiency after myocardial I/R injury is VWF dependent

To determine whether exacerbated myocardial I/R injury in Adamts13−/− mice was associated with increased acute inflammation, we measured neutrophil influx in the infarcted and surrounding regions of the perfused heart after 30 minutes of ischemia and 23.5 hours of reperfusion injury. Adamts13−/− mice demonstrated significantly increased extravascular neutrophil infiltration (487 ± 21/mm2) compared with WT mice (375 ± 24/mm2; P < .05; Figure 4A-B). In contrast, Vwf−/− mice exhibited significantly reduced neutrophil infiltration (262 ± 23/mm2) compared with WT mice (375 ± 24/mm2; P < .001; Figure 4A-B). Increased extravascular neutrophil infiltration in the infarcted region of Adamts13−/− mice was dependent on VWF, because neutrophils accumulation in the infarcted regions of Adamts13−/−/Vwf−/− mice (283 ± 27/mm2) was similar to that in Vwf−/− mice (262 ± 23/mm2; P = .56; Figure 4A-B). These results suggest that ADAMTS13 deficiency enhances neutrophil recruitment during reperfusion injury via a VWF-dependent mechanism, which may contribute to larger infarct volume after myocardial I/R injury.

ADAMTS13 deficiency-mediated enhanced neutrophil recruitment is VWF dependent. (A) Representative photomicrographs stained for neutrophils (Ly6B.2-positive cells are stained brown and indicated by the black arrows) and counterstained with hematoxylin from one mouse of each genotype. Scale bar indicates 50 μm. (B) Quantification of immunoreactive cells in the infarcted and surrounding region. Each dot is a mean of 16 fields from 4 serial sections (separated by 30 μm) per mouse. Horizontal bars indicate mean values. NS indicates nonsignificant.

ADAMTS13 deficiency-mediated enhanced neutrophil recruitment is VWF dependent. (A) Representative photomicrographs stained for neutrophils (Ly6B.2-positive cells are stained brown and indicated by the black arrows) and counterstained with hematoxylin from one mouse of each genotype. Scale bar indicates 50 μm. (B) Quantification of immunoreactive cells in the infarcted and surrounding region. Each dot is a mean of 16 fields from 4 serial sections (separated by 30 μm) per mouse. Horizontal bars indicate mean values. NS indicates nonsignificant.

Enhanced myocyte apoptosis after myocardial I/R injury in Adamts13−/− mice is VWF dependent

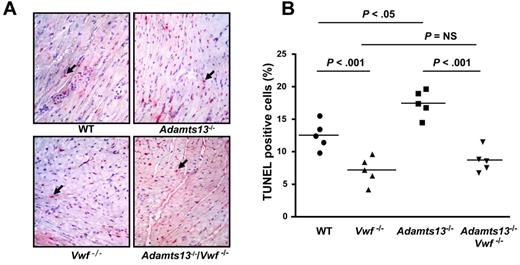

It is known that apoptosis contributes to myocardial I/R injury.34 In the present study, we investigated whether exacerbated myocardial I/R injury in Adamts13−/− mice is associated with increased myocyte apoptosis and, if so, whether it is dependent on VWF. We quantitated apoptosis by TUNEL staining of left ventricular sections from WT, Adamts13−/−, Vwf−/−, and Adamts13−/−/Vwf−/− mice. Adamts13−/− mice exhibited significantly increased myocyte apoptosis (17.5% ± 0.9%) compared with WT mice (12.4% ± 0.8%; P < .05; Figure 5A-B). Conversely, Vwf−/− mice exhibited significantly decreased myocyte apoptosis (7.1% ± 0.9%) compared with WT mice (12.4% ± 0.8%; P < .001; Figure 5A-B). Myocyte apoptosis in Adamts13−/−/Vwf−/− mice (8.6% ± 0.8%) was similar to that in Vwf−/− mice (7.1% ± 0.9%; P = .25), suggesting that increased myocyte apoptosis in Adamts13−/− mice was VWF dependent (Figure 5A-B).

ADAMTS13 deficiency promotes myocyte apoptosis, whereas VWF-deficiency prevents it. (A) Representative photomicrographs stained for apoptotic myocytes using the TUNEL method and counterstained with hematoxylin from 1 mouse of each genotype. TUNEL positive cells are stained red and indicated by black arrows. (B) Quantification of TUNEL-positive cells in the infarcted region. Each dot is a mean of 16 fields from 4 serial sections (separated by 30 μm) per mouse. Horizontal bars indicate mean values. NS indicates nonsignificant.

ADAMTS13 deficiency promotes myocyte apoptosis, whereas VWF-deficiency prevents it. (A) Representative photomicrographs stained for apoptotic myocytes using the TUNEL method and counterstained with hematoxylin from 1 mouse of each genotype. TUNEL positive cells are stained red and indicated by black arrows. (B) Quantification of TUNEL-positive cells in the infarcted region. Each dot is a mean of 16 fields from 4 serial sections (separated by 30 μm) per mouse. Horizontal bars indicate mean values. NS indicates nonsignificant.

Discussion

Several case-control studies have suggested that elevated plasma VWF levels and reduced ADAMTS13 Ag levels are associated with an increased risk of acute myocardial infarction.11,12,14,16,35 However, these studies did not determine whether the ADAMTS13-VWF axis contributes directly to the pathophysiology of acute myocardial infarction. Elevated levels of VWF in the plasma may be secondary to endothelial dysfunction and/or injury associated with myocardial infarction.35 Similarly, reduced plasma ADAMTS13 levels may be associated with its consumption and/or incorporation into thrombi together with its substrate VWF.14 This prompted us to investigate the functional role of ADAMTS13 and VWF in acute myocardial I/R injury. In the present study, we provide for the first time to our knowledge evidence that severe ADAMTS13 deficiency in mice exacerbates acute myocardial I/R injury, whereas VWF deficiency reduces it. Interestingly, exacerbated myocardial I/R injury in Adamts13−/− mice was VWF dependent. The results from this study and several case-control studies11,12,14,16,35 suggest that VWF and ADAMTS13 are causally involved in the pathogenesis of myocardial infarction.

There are several possibilities as to how ADAMTS13 reduces VWF-mediated myocardial I/R injury. First, we speculate that during reperfusion injury, ADAMTS13, by cleaving hyperactive ULVWF multimers and/or VWF multimers, inhibits thrombosis in capillaries, thus preventing microvascular ischemia. This speculation is based on recently published studies by us and others in murine models.20,36 On endothelial activation by calcium ionophore, a secretagogue of Weibel-Palade bodies, ADAMTS13 deficiency in mice results in spontaneous thrombus formation in microvessels.36 Spontaneous thrombus formation was absent in WT mice.36 Consistent with this finding, another study showed that regional cerebral blood flow after 30 minutes of reperfusion injury was markedly decreased in Adamts13−/− mice compared with WT mice, most likely because of occlusive thrombi in the cerebral microvasculature.20

Second, we hypothesize that by cleaving hyperactive ULVWF multimers and/or VWF multimers, ADAMTS13 may reduce acute inflammation and subsequent myocardial I/R injury. Recently, we and others have demonstrated that in addition to its role in thrombosis, the ADAMTS13-VWF axis also functions in the modulation of inflammatory responses.17-19,25 In the present study, we found that ADAMTS13 deficiency resulted in increased neutrophil infiltration in the infarcted and surrounding region after myocardial I/R injury, whereas VWF deficiency had the opposite effect. Increased neutrophil infiltration in Adamts13−/− mice was VWF dependent. Our findings of VWF-dependent increased neutrophil influx in the ischemic myocardium of Adamts13−/− mice are consistent with recent findings in an acute ischemic stroke model.24,25 Previously, it was shown that ADAMTS13 deficiency results in increased neutrophil extravasation in the murine model of thioglycollate-induced peritonitis via a VWF-dependent mechanism.17 Another study showed that VWF promotes neutrophil extravasation in a similar thioglycollate-induced peritonitis model.33 The results of these previous studies suggest that increased inflammation in Adamts13−/− mice may be due to direct proinflammatory properties of VWF.

Several studies have suggested that infiltrating neutrophils exacerbate myocardial I/R injury.37-39 Neutrophils contribute to myocardial I/R injury via several processes, including capillary occlusion with persistent microvascular ischemia, release of vasoconstrictive mediators, production of reactive oxygen species by myeloperoxidase and NADPH oxidase, release of proteolytic enzymes such as elastase and MMP9, and release of other inflammatory mediators such as platelet-activating factor and arachidonic acid metabolites.40 There are several possible mechanisms by which increased neutrophil infiltration in Adamts13−/− mice after myocardial I/R injury could occur through a VWF-dependent mechanism. First, activated platelets bound to endothelial ULVWF have been shown to support neutrophil tethering and rolling under high shear stress.41 Activated platelets also have been shown to promote acute inflammation by stimulating the release of Weibel-Palade bodies.42 We speculate that activated platelets release factors such as proinflammatory cytokines and other chemoattractants that generate signals for the recruitment and extravasation of neutrophils. Indeed, neutrophils have been shown to extravasate across inflamed endothelium via an interaction between endothelium-bound VWF and platelets mediated by platelet GPIbα.33,43 Some in vitro studies also suggest that neutrophils can interact with VWF directly, independently of platelets, via an interaction mediated by both neutrophil PSGL-1 and integrin αMβ2.44 These studies suggest that VWF could recruit neutrophils via platelet-dependent and platelet-independent mechanisms. Future studies will be required to define the role of platelets, particularly platelet GPIbα, in the VWF-mediated increased neutrophil influx after myocardial I/R injury.

Finally, we have shown herein that ADAMTS13 deficiency in mice promotes myocyte apoptosis, whereas VWF deficiency has the opposite effect. Interestingly, increased myocyte apoptosis in Adamts13−/− mice was VWF dependent. Myocyte apoptosis is known to be limited to the infarcted region and plays an important role in exacerbating myocardial I/R injury.34 Apoptosis is regulated by multiple factors, such as production of reactive oxygen species by myeloperoxidase and NADPH oxidase, release of the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6, and neutrophils.45,46 Based on recent findings in an ischemic stroke model, we hypothesize that enhanced myocyte apoptosis in Adamts13−/− mice is caused by multiple factors, including an increase in myeloperoxidase activity and expression of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNFα.24

There are several limitations of this study when extrapolating mice data to humans. First, patients with acute myocardial infarction often have only partially reduced ADAMTS13 activity and increased VWF levels.11-16 In the present study, we show that partial reduction in ADAMTS13 Ag level (50% of normal levels) in Adamts13+/− mice did not have any effect on infarct size, suggesting that approximately 50% of ADAMTS13 activity in plasma is sufficient to prevent exacerbated myocardial I/R injury. Future studies would be required to determine whether partial reduction of ADAMTS13 activity in combination with increased VWF levels exacerbate myocardial I/R injury. Second, species differences between murine and human ADAMTS13 may contribute to differences in the VWF dependency of I/R injury. Mice on the c57BL6/J genetic background express a truncated and less active variant of ADAMTS13 that lacks the C-terminal CUB domains (ADAMTS13S/S), whereas humans express full-length ADAMTS13 (ADAMTS13L/L).47 However, the ADAMTS13S/S variant cleaves ULVWF multimers with similar efficiency compared with ADAMTS13L/L under steady-state conditions in vivo.48 The third limitation is that arterial and venous flow rates also differ between mice and humans and these differences might influence VWF function.

In summary, in the present study, we have demonstrated that complete ADAMTS13 deficiency in mice exacerbates myocardial I/R injury, whereas complete VWF deficiency is protective. In addition, we have demonstrated that VWF deficiency abrogates aggravated myocardial I/R injury in ADAMTS13-deficient mice. Our results in mice suggest that VWF and ADAMTS13 are likely to be causally involved in myocardial I/R injury.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants HL063943, HL062984, and NS024621 to S.R.L and grant HL076539 to D.G.M.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: C.G. performed the experiments, analyzed the results, and wrote the manuscript; D.G.M. and S.R L. contributed important intellectual insights and edited the manuscript; M.J. performed the experiments; and A.K.C. directed the project, designed the study, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Anil K. Chauhan, PhD, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Iowa, 3160 Medical Labs, 25 S Grand Ave, Iowa City, IA 52242; e-mail: anil-chauhan@uiowa.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal