Abstract

EZH2, a catalytic component of the polycomb repressive complex 2, trimethylates histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27) to repress the transcription of target genes. Although EZH2 is overexpressed in various cancers, including some hematologic malignancies, the role of EZH2 in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) has yet to be examined in vivo. In the present study, we transformed granulocyte macrophage progenitors from Cre-ERT;Ezh2flox/flox mice with the MLL-AF9 leukemic fusion gene to analyze the function of Ezh2 in AML. Deletion of Ezh2 in transformed granulocyte macrophage progenitors compromised growth severely in vitro and attenuated the progression of AML significantly in vivo. Ezh2-deficient leukemic cells developed into a chronic myelomonocytic leukemia–like disease with a lower frequency of leukemia-initiating cells compared with the control. Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing revealed a significant reduction in the levels of trimethylation at H3K27 in Ezh2-deficient leukemic cells, not only at Cdkn2a, a known major target of Ezh2, but also at a cohort of genes relevant to the developmental and differentiation processes. Overexpression of Egr1, one of the derepressed genes in Ezh2-deficient leukemic cells, promoted the differentiation of AML cells profoundly. Our findings suggest that Ezh2 inhibits differentiation programs in leukemic stem cells, thereby augmenting their leukemogenic activity.

Introduction

The polycomb group (PcG) of proteins function in gene silencing through histone modifications, forming the chromatin-associated multiprotein complexes known as polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1) and PRC2. These 2 complexes work together to maintain heritable chromatin modifications, mediating transcriptional repression of target genes,1 and have been characterized as general regulators of stem cells.

Among the PcG proteins, BMI1, a core component of PRC1, plays an essential role in the maintenance of the self-renewal ability of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), at least partially by silencing the CDKN2A (INK4A/ARF) locus.2-5 BMI1 also maintains the multipotency of HSCs by keeping developmental regulator gene promoters poised for activation.6 EZH2 is a catalytic component of PRC2 that trimethylates histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27) to repress its target genes transcriptionally. We recently reported that Ezh2 is essential for fetal but not adult HSCs.7 Ezh2-deficient embryos die of anemia because of insufficient expansion of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells and defective erythropoiesis in the fetal liver. Deletion of Ezh2 in adult BM perturbs lymphopoiesis but does not otherwise affect hematopoiesis.7-9 Ezh1 has been shown to compensate for Ezh2 deficiency in mouse embryonic stem cells,10 and may also act in a compensatory fashion in Ezh2-deficient BM HSCs.7 In contrast, overexpression of Ezh2 in HSCs reportedly prevents exhaustion of the long-term repopulating potential of HSCs during repeated serial transplantation.11

PcG genes have also been linked to cancer.12-14 Aberrant regulation of EZH2 and H3K27me3 has been reported in various cancers. EZH2 has been found to be overexpressed and/or amplified in prostate, breast, bladder, and colon cancers, and its expression is correlated with metastasis and a poor prognosis. EZH2 overexpression has also been found in high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and MDS-derived acute myeloid leukemia (AML).15 A somatic gain-of-function mutation of EZH2 (Tyr641) was identified in germinal center B cell–derived lymphoma.16 Genomic loss of mRNA-101, which regulates EZH2 expression negatively, has also been reported in some prostate and gastric cancers.17 In contrast, loss-of-function mutations of EZH2 have been reported in MDS, MDS overt AML (MDS/AML), and myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs).18,19 These previous results suggested that EZH2 can function as both a tumor suppressor and an oncogene depending on the context.

DNZep, an S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase inhibitor, has been shown to eradicate tumor-initiating hepatocellular carcinoma cells and to induce apoptosis preferentially in cancer cells in other cancers, including AML.20-22 DZNep inhibits S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase and causes the retention of S-adenosylhomocysteine, thereby inhibiting S-adenosyl-L-methionine–dependent methyltransferases such as EZH2.23 However, DZNep is not a specific inhibitor of EZH2, so it affects other S-adenosyl-L-methionine–dependent methyltransferases as well. Nevertheless, EZH2 might be critical to AML in vivo, but this relationship has yet to be addressed. In the present study, we investigated the role of Ezh2 in leukemogenesis using mice in which Ezh2 is conditionally deleted after tamoxifen treatment. Deletion of Ezh2 induced differentiation of leukemic cells and converted AML into an MDS/MPN-like disease. We propose that Ezh2 augments leukemogenic activity by reinforcing differentiation blockage in AML.

Methods

Mice

For conditional deletion of Ezh2, Ezh2fl/fl mice7 were crossed with Rosa::Cre-ERT mice (TaconicArtemis). C57BL/6 (CD45.2) mice were from Japan SLC. C57BL/6 mice congenic for the Ly5 locus (CD45.1) were from Sankyo-Lab Service. Mice were bred and maintained in the animal research facility of the Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University (Chiba, Japan) in accordance with institutional guidelines. This study was approved by the institutional review committees of Chiba University.

Purification of mouse GMPs

For purification of mouse granulocyte/macrophage progenitors (GMPs), BM mononuclear cells were isolated on Ficoll-Paque PLUS (GE Healthcare) and incubated with a mixture of biotin-conjugated mAbs against IL-7Rα, Sca-1, and lineage markers (Lin) including Gr-1, Ter-119, B220, CD4, and CD8α (eBiosciences and BioLegend). The cells were further stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD34, PE-conjugated anti-FcγRII/III, and allophycocyanin (APC)–conjugated anti–c-Kit Abs (eBiosciences). Biotinylated Abs were detected with streptavidin-APC-Cy7 (BD Biosciences). Four-color analysis and sorting of GMPs (IL-7Rα−Lin−Sca-1−c-Kit+CD34+FcγRII/IIIhi) were performed on a FACSCanto II or FACSAria II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Viral transduction of GMPs

pMX-neo-MLL-AF9 has been described previously.24 To produce the recombinant retrovirus, plasmid DNA was transfected into PlatE packaging cells by CaPO4 coprecipitation. Before transduction, GMPs were precultured for 24 hours in IMDM with 20% FCS, 40 ng/mL of SCF, 20 ng/mL of Flt3L (PeproTech), and 20 ng/mL of the chimeric protein of soluble IL-6Rα and IL-6 (FP6, kindly provided by Kirin Pharma). Cells were then spinoculated with retroviral supernatant in the presence of protamine sulfate (10 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 minutes at 1350g and 32°C. After the spinoculation, cells were further incubated for another 24 hours. To overexpress Ezh2 or Egr1 in MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs, murine Ezh2 and Egr1 were inserted into the CSII-IRES-EGFP lentivirus vector and the MIGR1 retrovirus vector, respectively. To produce lentiviruses, plasmid DNA was transfected into 293T cells along with the packaging plasmid (pMDLg/p.RRE) and the VSV-G– and Rev-expressing plasmid (pCMV-VSV-G-RSV-Rev) by CaPO4 coprecipitation. Supernatants from transfected cells were concentrated by centrifugation at 6000g for 16 hours, and then resuspended in α-MEM supplemented with 1% FCS (1/100 of the initial volume of supernatant).

In vitro culture and colony assays of MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs

GMPs transduced with MLL-AF9 were plated in methylcellulose medium (Methocult M3234; StemCell Technologies) containing 50 ng/mL of SCF, 10 ng/mL of IL-6, 10 ng/mL of GM-CSF, and 10 ng/mL of IL-3. After 5 days of culture, colonies were counted and pooled and then 1 × 104 cells were replated in the same medium. To delete Ezh2, MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs from the fourth round of culture were transferred to IMDM with 20% FCS, 10 ng/mL of SCF, 10 ng/mL of FP6, 10 ng/mL of GM-CSF, 10 ng/mL of IL-3, and 200nM 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT). After 24 hours of culture, cells were washed with PBS and replaced in the same medium without 4-OHT. For growth assays, 1 × 104 cells after 4-OHT treatment were transferred to liquid culture in 96- or 48-well plates containing IMDM with 20% FCS and the above-mentioned cytokines. Cell-cycle status and apoptosis were examined using an APC BrdU Flow kit (BD Pharmingen). For colony replating assays, after 4-OHT treatment, cells were cultured in methylcellulose medium containing the above-mentioned cytokines and 100nM 4-OHT. The cultures were carried out in triplicate.

BM transplantation

The fourth or fifth round of replated cells (CD45.2) before 4-OHT treatment (4 × 105) were transplanted into lethally irradiated CD45.1 mice along with 2 × 105 BM cells (CD45.1) for radioprotection. To induce Cre activity, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 100 μL of tamoxifen dissolved in corn oil at a concentration of 10 mg/mL once a day for 5 consecutive days. The chimerism of donor-derived hematopoiesis was monitored by flow cytometry. Peripheral blood (PB) cells were stained with a mixture of mAbs including PE–anti–Gr-1, APC–anti–Mac-1, PE-Cy7–anti-CD45.1, and Pacific Blue–anti-CD45.2. Biotinylated Abs were detected with streptavidin–APC-Cy7. WBC counts of PB were made using an automated cell counter (Celltec α; Nihon Kohden).

Microarray analysis

The CD45.2+Mac1+IL-7Rα−Lin− (except for Mac1) Sca-1−c-Kit+FcγRII/IIIhi fraction enriched in leukemia-initiating cells (LICs) was purified from the BM of recipient mice with Cre-ERT;Ezh2+/+ (control) or Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemia. RNA was isolated using TRIzol LS Reagent (Invitrogen). The quantity and purity of RNA was analyzed on an ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies) and a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). Microarray analysis was performed using Affymetrix Mouse Genome 430 Version 2.0 arrays, which contain more than 39 000 transcripts representing 34 000 genes. Labeling, hybridization washing, and scanning of the microarray were performed following the manufacturer's specifications (Affymetrix). The arrays were scanned on the GCS 3000 Affymetrix high-resolution scanner and analyzed using the GeneChip Operating Version 1.4 software (Affymetrix) and GeneSpring Version 7.3.1 (Agilent Technologies). Normalization was performed using the Microarray Suite 5 algorithm and only gene expression levels with statistical significance (P < .05) were recorded as being “present” above background levels. Genes with expression levels below this statistical threshold were considered “absent.” We performed the experiments in duplicate and selected the genes exhibiting a change greater than 2-fold. The raw data were deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus under the accession number GSE33808.

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using TRIZOL LS solution (Invitrogen) and reverse-transcribed by the ThermoScript RT-PCR system (Invitrogen) with an oligo-dT primer. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed with an ABI Prism 7300 Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems) using FastStart Universal Probe Master (Roche) and the indicated combinations of Universal Probe Library (Roche) and primers listed in supplemental Table 4 (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Western blot analysis of trimethylation of H3K27 (H3K27me3)

Cells were lysed in 100mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150mM NaCl, 1.5mM MgCl2, 0.65% NP-40, and protease inhibitor cocktail (cOmplete mini; Roche). After centrifugation, nuclei pellets were extracted with 0.2N HCl, and acid-soluble histones were precipitated with trichloroacetic acid. Histones were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a PVDF membrane, and detected by Western blotting using anti-H3 (ab1791; Abcam) and anti-H3K27me3 (07-449; Millipore).

GO and gene set enrichment analysis

We performed gene ontology (GO) analysis using biologic process annotations in the GO database.25 The significance of each term was determined using Fisher exact test and the Bonferroni adjustment for multiple testing. The P value reflects the likelihood that we would observe such enrichment by chance.

ChIP assay and ChIP-Seq

Detailed methods for the ChIP assay and the ChIP assay coupled with massive parallel sequencing (ChIP-Seq) are described in supplemental Methods.

Micrographs

Images were taken with a BZ-9000 series All-in-One fluorescence microscope BIOREVO (Keyence) and processed using Adobe PhotoShop CS3 (Adobe Systems Inc).

Results

Deletion of Ezh2 compromises proliferative capacity of MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs

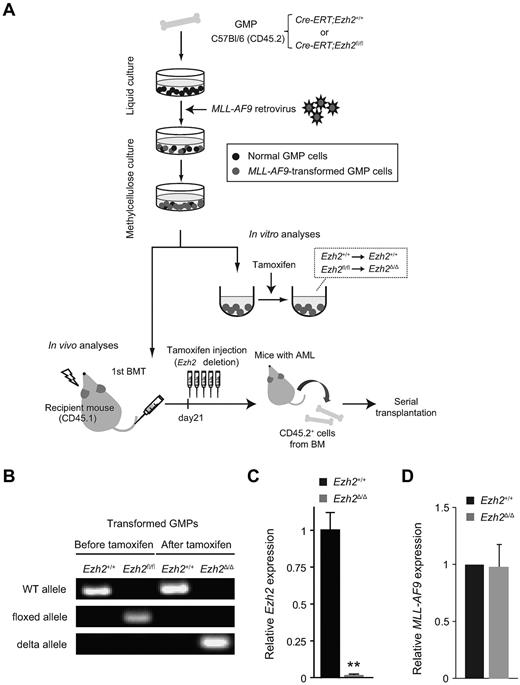

To examine the role of Ezh2 in myeloid leukemia, we made use of the myeloid leukemia model induced by the leukemic fusion gene MLL-AF9. MLL-AF9 can transform GMPs directly into immortalized leukemic blast cells in vitro, and mice infused with these cells develop AML.26 We purified IL-7Rα−Lin−Sca-1−c-Kit+CD34+FcγRII/IIIhi GMPs from both Cre-ERT;Ezh2+/+ control and Cre-ERT;Ezh2fl/fl mice, transduced them with an MLL-AF9 retrovirus, and then serially replated the transduced cells in methylcellulose medium (Figure 1A). Transformed cells are enriched during repeated replating, whereas nontransformed cells fail to survive and proliferate beyond the fourth replating. To select the transformed cells, we replated the transformed GMPs more than 3 times before using the cells in our experiments. Ezh2 was then deleted by inducing nuclear translocation of Cre by treating transformed GMPs with 4-OHT. Efficient deletion of Ezh2 was confirmed by genomic PCR and qRT-PCR (Figure 1B-C). Hereafter, Ezh2Δ/Δ denotes Cre-ERT;Ezh2fl/fl after removal of exons 18 and 19. We also confirmed that the expression of MLL-AF9 in control and Ezh2Δ/Δ–transformed cells was equivalent by qRT-PCR (Figure 1D).

Induced deletion of Ezh2 in MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs. (A) Schematic diagram of the experimental process. GMPs purified from Cre-ERT;Ezh2+/+ or Cre-ERT;Ezh2fl/fl mice were transduced with MLL-AF9 and cultured in methylcellulose medium. For deletion of Ezh2 in vitro, MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs were transferred to liquid medium containing 200nM 4-OHT. MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs were also transplanted into lethally irradiated recipient mice together with wild-type BM cells for radioprotection. For deletion of Ezh2 in vivo, 100 μL of tamoxifen (10 mg/mL) was IP injected once a day for 5 consecutive days at 3 weeks after transplantation. For serial transplantation assays, CD45.2+ leukemic cells were sorted from primary recipient mice with overt leukemia and transplanted into sublethally irradiated secondary recipient mice. (B) Efficient deletion of Ezh2 in MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs detected by genomic PCR. Representative genomic PCR showing the deletion of Ezh2 in Cre-ERT;Ezh2fl/flMLL-AF9–transformed GMPs after culture in the presence of 200nM 4-OHT for 24 hours. “WT,” “floxed,” and “Δ” alleles indicate the wild-type allele, floxed Ezh2 allele, and floxed Ezh2 allele after removal of exons 18 and 19 by Cre recombinase, respectively. (C) Expression of Ezh2 in MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs in culture after Ezh2 deletion. mRNA levels of Ezh2 were evaluated by qRT-PCR and normalized to Hprt1 expression. Data are shown as the means ± SD for triplicate analyses. **P < .01. (D) Expression of MLL-AF9 in MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs in culture after Ezh2 deletion. mRNA levels of MLL-AF9 were evaluated by qRT-PCR and normalized to β-actin (Actb) expression. Data are shown as the means ± SD for triplicate analyses.

Induced deletion of Ezh2 in MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs. (A) Schematic diagram of the experimental process. GMPs purified from Cre-ERT;Ezh2+/+ or Cre-ERT;Ezh2fl/fl mice were transduced with MLL-AF9 and cultured in methylcellulose medium. For deletion of Ezh2 in vitro, MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs were transferred to liquid medium containing 200nM 4-OHT. MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs were also transplanted into lethally irradiated recipient mice together with wild-type BM cells for radioprotection. For deletion of Ezh2 in vivo, 100 μL of tamoxifen (10 mg/mL) was IP injected once a day for 5 consecutive days at 3 weeks after transplantation. For serial transplantation assays, CD45.2+ leukemic cells were sorted from primary recipient mice with overt leukemia and transplanted into sublethally irradiated secondary recipient mice. (B) Efficient deletion of Ezh2 in MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs detected by genomic PCR. Representative genomic PCR showing the deletion of Ezh2 in Cre-ERT;Ezh2fl/flMLL-AF9–transformed GMPs after culture in the presence of 200nM 4-OHT for 24 hours. “WT,” “floxed,” and “Δ” alleles indicate the wild-type allele, floxed Ezh2 allele, and floxed Ezh2 allele after removal of exons 18 and 19 by Cre recombinase, respectively. (C) Expression of Ezh2 in MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs in culture after Ezh2 deletion. mRNA levels of Ezh2 were evaluated by qRT-PCR and normalized to Hprt1 expression. Data are shown as the means ± SD for triplicate analyses. **P < .01. (D) Expression of MLL-AF9 in MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs in culture after Ezh2 deletion. mRNA levels of MLL-AF9 were evaluated by qRT-PCR and normalized to β-actin (Actb) expression. Data are shown as the means ± SD for triplicate analyses.

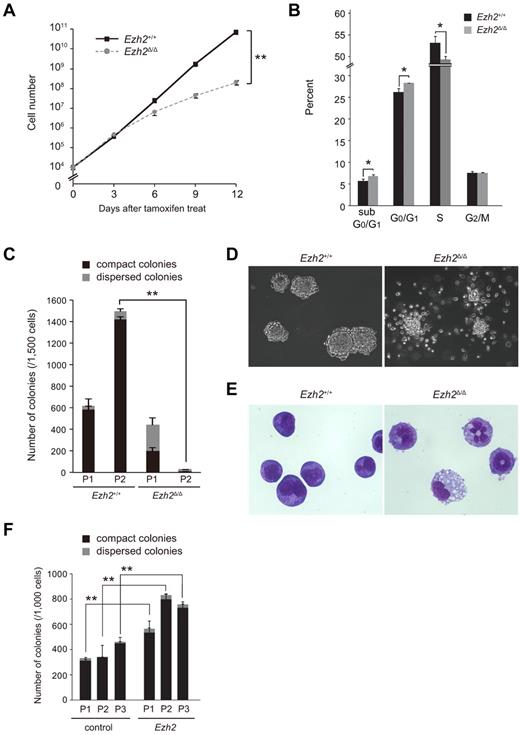

To understand the role of Ezh2 in the MLL-AF9–induced transformation of GMPs, we examined the cell growth and colony-forming ability of transformed GMPs. We found that proliferation of Ezh2Δ/Δ transformed GMPs was severely compromised in liquid culture (Figure 2A). Deletion of Ezh2 significantly retarded cell-cycle entry and resulted in increased apoptotic cell death (Figure 2B). Similarly, the number of total colonies generated by Ezh2Δ/Δ cells in the secondary replating assays was considerably less than that of the control (Figure 2C). Ezh2Δ/Δ cells tended to form dispersed colonies that were mainly composed of differentiated myeloid cells, whereas control cells mostly formed compact colonies composed of myeloblasts (Figure 2C-E). The proportion of dispersed colonies in the Ezh2Δ/Δ cell culture increased with serial replatings. The frequency was approximately 50% in the primary plating, and eventually reached 90% in the tertiary plating (Figure 2C and data not shown). Therefore, deletion of Ezh2 affects the growth and replating capacity of transformed GMPs profoundly in vitro. Ezh2+/Δ cells showed a colony-forming capacity intermediate between wild-type and Ezh2Δ/Δ cells, indicating that the transforming capacity of MLL-AF9 is dependent on Ezh2 levels (supplemental Figure 1).

Deletion of Ezh2 compromises the proliferative capacity of MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs. (A) Growth of MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs after deletion of Ezh2. MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs (1 × 104 cells each) with the indicated genotypes were cultured in IMDM with 20% FCS, SCF, FP6, GM-CSF, and IL-3 (10 ng/mL each) and their growth monitored every 3 days. The data are shown as the means ± SD for triplicate analyses. **P < .01. (B) Cell-cycle status and apoptosis of MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs after deletion of Ezh2. MLL-AF9–transformed Ezh2+/+ and Ezh2Δ/Δ GMPs in panel A were pulsed with BrdU for 30 minutes and then stained with anti-BrdU Ab and 7-amino-actinomycin D. The percentage of cells in each phase of cell cycle and sub-G0/G1 apoptotic cells are shown as the means ± SD for triplicate analyses in a bar graph. *P < .05. (C) Replating efficiency of MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs after deletion of Ezh2. MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs (1500 cells) with the indicated genotypes were serially replated in methylcellulose medium containing 50 ng/mL of SCF, 10 ng/mL of FP6, 10 ng/mL of GM-CSF, 10 ng/mL of IL-3, and 100nM 4-OHT. The black and gray bars represent compact and dispersed colonies, respectively. The data are shown as the means ± SD for triplicate analyses. **P < .01. P1 and P2 denote platings 1 and 2, respectively. (D) Morphology of MLL-AF9–transformed GMP colonies. Representative colonies with indicated genotypes observed under an inverted microscope are depicted. Magnification ×100. (E) Typical cell morphology of MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs with indicated genotypes after 2 rounds of plating. Cells were cytospun onto glass slides and observed after May-Giemsa staining. Magnification ×400. (F) Effect of overexpression of Ezh2 in replating efficiency of MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs. MLL-AF9–transformed Cre-ERT;Ezh2+/+ GMPs were infected with a control vector virus or an Ezh2 lentivirus. Infected cells were purified by cell sorting using green fluorescent protein as a marker, and were serially replated as in panel C without 4-OHT. The black and gray bars represent compact and dispersed colonies, respectively. The data are shown as the means ± SD for triplicate analyses. **P < .01. P1, P2, and P3 denote platings 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

Deletion of Ezh2 compromises the proliferative capacity of MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs. (A) Growth of MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs after deletion of Ezh2. MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs (1 × 104 cells each) with the indicated genotypes were cultured in IMDM with 20% FCS, SCF, FP6, GM-CSF, and IL-3 (10 ng/mL each) and their growth monitored every 3 days. The data are shown as the means ± SD for triplicate analyses. **P < .01. (B) Cell-cycle status and apoptosis of MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs after deletion of Ezh2. MLL-AF9–transformed Ezh2+/+ and Ezh2Δ/Δ GMPs in panel A were pulsed with BrdU for 30 minutes and then stained with anti-BrdU Ab and 7-amino-actinomycin D. The percentage of cells in each phase of cell cycle and sub-G0/G1 apoptotic cells are shown as the means ± SD for triplicate analyses in a bar graph. *P < .05. (C) Replating efficiency of MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs after deletion of Ezh2. MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs (1500 cells) with the indicated genotypes were serially replated in methylcellulose medium containing 50 ng/mL of SCF, 10 ng/mL of FP6, 10 ng/mL of GM-CSF, 10 ng/mL of IL-3, and 100nM 4-OHT. The black and gray bars represent compact and dispersed colonies, respectively. The data are shown as the means ± SD for triplicate analyses. **P < .01. P1 and P2 denote platings 1 and 2, respectively. (D) Morphology of MLL-AF9–transformed GMP colonies. Representative colonies with indicated genotypes observed under an inverted microscope are depicted. Magnification ×100. (E) Typical cell morphology of MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs with indicated genotypes after 2 rounds of plating. Cells were cytospun onto glass slides and observed after May-Giemsa staining. Magnification ×400. (F) Effect of overexpression of Ezh2 in replating efficiency of MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs. MLL-AF9–transformed Cre-ERT;Ezh2+/+ GMPs were infected with a control vector virus or an Ezh2 lentivirus. Infected cells were purified by cell sorting using green fluorescent protein as a marker, and were serially replated as in panel C without 4-OHT. The black and gray bars represent compact and dispersed colonies, respectively. The data are shown as the means ± SD for triplicate analyses. **P < .01. P1, P2, and P3 denote platings 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

We next evaluated the effect of overexpression of Ezh2 in MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs by first infecting wild-type MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs with an Ezh2 lentivirus. We purified green fluorescent protein–positive cells by cell sorting and performed replating assays. qRT-PCR confirmed that Ezh2 was expressed at least 35-fold more than the control. As expected, overexpression of Ezh2 increased the colony-forming potential of transformed GMPs significantly during serial replatings (Figure 2F).

Deletion of Ezh2 perturbs the progression of leukemia and reduces the frequency of LICs

To investigate the effect of Ezh2 deletion on MLL-AF9–induced leukemias in vivo, we transplanted either Cre-ERT;Ezh2+/+ or Cre-ERT;Ezh2fl/flMLL-AF9–transformed GMPs (4 × 105 cells, CD45.2+) into lethally irradiated recipient mice along with 2 × 105 CD45.1+ wild-type BM cells for radioprotection (Figure 1A). At day 21, significant donor chimerism was detected in the PB (supplemental Figure 2A). Disease onset was confirmed by verifying that 3 × 106 BM cells from mice at day 21 could initiate AML in all secondary recipient mice (n = 3). From day 21, Ezh2 was deleted by intraperitoneally injecting tamoxifen once a day for 5 consecutive days. Ezh2 was as efficiently deleted in vivo as it was in vitro, and the loss of Ezh2 was maintained even in terminal leukemias (supplemental Figure 2B). Deletion of Ezh2 appeared to perturb the progression of leukemia (supplemental Figure 2C) and to prolong the survival of recipient mice significantly (Figure 3A, 60 vs 76 days, P < .0001). However, all of the mice eventually died of leukemia, and the moribund mice with Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemias displayed hepatosplenomegaly with massive infiltration of leukemic cells, similar to the mice with Ezh2+/+ leukemias (supplemental Figure 3). MLL-AF9–transformed cells have been reported to express high levels of myeloid lineage–specific antigens, including Mac-1 and/or Gr-1, whereas a somewhat lower percentage of cells express F4/80, a marker specific to monocytic cells.26,27 Flow cytometric analysis of CD45.2+ donor cells from BM of moribund mice showed that almost all cells were positive for Mac-1 and FcγRII/III, and 70%-80% of cells expressed F4/80. No significant differences were detected in the proportion of positive cells or the expression levels of myeloid antigens between Ezh2+/+ and Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemic cells. However, Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemic cells had a higher frequency of Gr-1hi cells compared with control leukemic cells, suggesting a greater incidence of differentiation (Figure 3B and data not shown). Morphologic analysis of Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemic cells from the BM and PB revealed a greater degree of differentiation than in control leukemic cells, and the frequency of leukemic blasts in the BM of recipient mice with Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemias was found to be less than 20%, compared with greater than 50% in control leukemias. Instead, Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemias had more granulocytic and monocytic cells, as well as cells with characteristics of both granulocytes and monocytes (Figure 3C-D). In addition, dysplasias were evident in both Ezh2+/+ and Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemic cells, including abnormal chromatin patterns, granulation, and segmentation features of both granulocytes and monocytes (Figure 3D). Based on the World Health Organization classification,28 Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemias more closely resemble chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) rather than AML, suggesting that deletion of Ezh2 converts AML into an MDS/MPN-like disease. Ezh2Δ/Δ AML cells from moribund mice gave rise to 10-fold fewer colonies in methylcellulose medium compared with the control (Figure 3E), and again showed a greater tendency to differentiate compared with control cells (Figure 3F). These observations imply that Ezh2 is critical for the progression of MLL-AF9–induced AML and is involved in a differentiation blockage in AML cells.

Deletion of Ezh2 induces the differentiation of AML cells and prolongs the survival of diseased mice. (A) Overall survival of mice injected with 4 × 105Ezh2+/+ or Ezh2Δ/ΔMLL-AF9–transformed cells compared by Kaplan-Meier analysis (n = 9). **P < .01. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of CD45.2+ leukemic cells from BM of recipient mice. The profiles of Gr-1 expression are presented in histograms and the frequencies of the Gr-1hi fractions and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) are also indicated. Representative data from multiple experiments are shown. (C) Pie graphs illustrating the relative frequency of blasts, monocytic cells, granulocytic cells, and granulocytic/monocytic (GM) cells (cells with characteristics of both granulocytes and monocytes) in CD45.2+ leukemic cells from BM and PB of moribund mice with advanced leukemia. Cells were cytospun onto glass slides and Wright-Giemsa stained. The frequencies were calculated by counting 500 cells 3 times and the average values are depicted. (D) Representative morphology of leukemic cells from BM in panel C. Magnification ×400 (top panels), ×1000 (bottom panels). (E) Colony assay of leukemic cells from BM of recipient mice with overt leukemia. CD45.2+ BM cells (5000 cells each) with indicated genotypes were plated in methylcellulose medium containing 50 ng/mL of SCF, 10 ng/mL of FP6, 10 ng/mL of GM-CSF, and 10 ng/mL of IL-3. The black and gray bars represent compact and dispersed colonies, respectively. The data are shown as the means ± SD for triplicate analyses. **P < .01. Magnification ×100 (top panels), ×200 (bottom panels). (F) Representative colonies in panel E observed under an inverted microscope at the indicated magnifications.

Deletion of Ezh2 induces the differentiation of AML cells and prolongs the survival of diseased mice. (A) Overall survival of mice injected with 4 × 105Ezh2+/+ or Ezh2Δ/ΔMLL-AF9–transformed cells compared by Kaplan-Meier analysis (n = 9). **P < .01. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of CD45.2+ leukemic cells from BM of recipient mice. The profiles of Gr-1 expression are presented in histograms and the frequencies of the Gr-1hi fractions and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) are also indicated. Representative data from multiple experiments are shown. (C) Pie graphs illustrating the relative frequency of blasts, monocytic cells, granulocytic cells, and granulocytic/monocytic (GM) cells (cells with characteristics of both granulocytes and monocytes) in CD45.2+ leukemic cells from BM and PB of moribund mice with advanced leukemia. Cells were cytospun onto glass slides and Wright-Giemsa stained. The frequencies were calculated by counting 500 cells 3 times and the average values are depicted. (D) Representative morphology of leukemic cells from BM in panel C. Magnification ×400 (top panels), ×1000 (bottom panels). (E) Colony assay of leukemic cells from BM of recipient mice with overt leukemia. CD45.2+ BM cells (5000 cells each) with indicated genotypes were plated in methylcellulose medium containing 50 ng/mL of SCF, 10 ng/mL of FP6, 10 ng/mL of GM-CSF, and 10 ng/mL of IL-3. The black and gray bars represent compact and dispersed colonies, respectively. The data are shown as the means ± SD for triplicate analyses. **P < .01. Magnification ×100 (top panels), ×200 (bottom panels). (F) Representative colonies in panel E observed under an inverted microscope at the indicated magnifications.

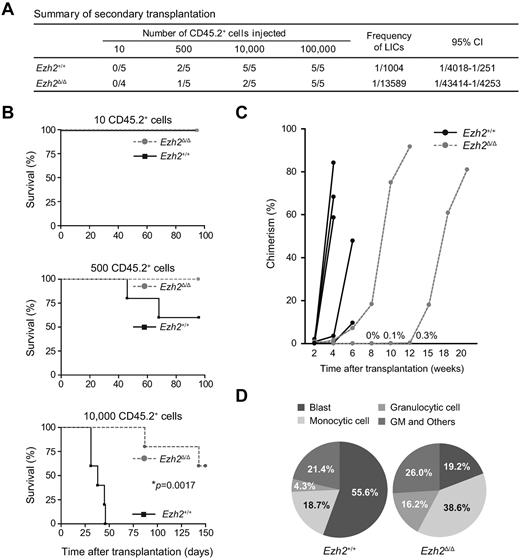

To determine whether Ezh2 plays a key role in the maintenance of LICs, we next examined the frequency of LICs in the primary leukemias. We first selected primary recipients at similar stages of leukemia based on PB chimerism at day 21 just before tamoxifen treatment (supplemental Table 1). Limiting doses of CD45.2+ leukemic cells purified from the BM of primary recipients were infused into secondary recipients irradiated at a sublethal dose. The frequency of LICs in CD45.2+Ezh2+/+ leukemic cells was found to be approximately 0.1%, whereas the frequency of LICs in CD45.2+Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemic cells was much lower (0.007%; Figure 4A). Ten thousand control cells were enough to induce fatal leukemia in all 5 recipient mice, whereas only 2 of 5 recipient mice died from the same dose of Ezh2Δ/Δ cells (Figure 4B). Whereas control secondary leukemias were more malignant than control primary leukemias (median survival, 60 days for primary recipients vs 38 days for secondary recipients, P = .0004), progression of Ezh2-null secondary leukemias was much slower than the progression of Ezh2-null primary leukemias (Figure 4C). Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemias again showed an apparent tendency to differentiate, had a BM composition that was less than 20% leukemic blasts, and showed dysplasias that mimicked CMML (Figure 4D). These data indicate that the frequency of LICs is reduced in Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemias compared with control leukemias, and that the progression of Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemias is further perturbed during serial transplantation.

Deletion of Ezh2 attenuates the progression of leukemia and causes a reduction in the frequency of LICs. (A) Summary of secondary transplantation of primary leukemic cells. Limiting numbers of Ezh2+/+ or Ezh2Δ/Δ CD45.2+ leukemic cells isolated from BM of primary recipients were transplanted immediately into sublethally irradiated secondary recipient mice (CD45.1+). Mice with chimerism of more than 1% in the PB at 20 weeks after transplantation were considered to be engrafted successfully, and the others were defined as negative mice. The frequencies of positive mice and LICs and the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) are indicated in the table. (B) Overall survival of mice injected with Ezh2+/+ or Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemic cells (10, 500, or 10 000 cells; n = 5 each, *P = .0017). (C) Percent chimerism of donor cells in PB. The chimerism of CD45.2+ donor-derived cells in PB of recipients infused with 10 000 leukemic cells was examined after transplantation. Three mice with Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemic cells did not show engraftment of donor cells (n = 5 each). (D) Pie graphs illustrating the relative frequency of blasts, monocytic cells, granulocytic cells, and granulocytic/monocytic (GM) cells in CD45.2+ leukemic cells from BM of moribund mice with advanced leukemia. Cells were cytospun onto glass slides and Wright-Giemsa stained. The frequencies were calculated by counting 500 cells 3 times and the average values are depicted.

Deletion of Ezh2 attenuates the progression of leukemia and causes a reduction in the frequency of LICs. (A) Summary of secondary transplantation of primary leukemic cells. Limiting numbers of Ezh2+/+ or Ezh2Δ/Δ CD45.2+ leukemic cells isolated from BM of primary recipients were transplanted immediately into sublethally irradiated secondary recipient mice (CD45.1+). Mice with chimerism of more than 1% in the PB at 20 weeks after transplantation were considered to be engrafted successfully, and the others were defined as negative mice. The frequencies of positive mice and LICs and the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) are indicated in the table. (B) Overall survival of mice injected with Ezh2+/+ or Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemic cells (10, 500, or 10 000 cells; n = 5 each, *P = .0017). (C) Percent chimerism of donor cells in PB. The chimerism of CD45.2+ donor-derived cells in PB of recipients infused with 10 000 leukemic cells was examined after transplantation. Three mice with Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemic cells did not show engraftment of donor cells (n = 5 each). (D) Pie graphs illustrating the relative frequency of blasts, monocytic cells, granulocytic cells, and granulocytic/monocytic (GM) cells in CD45.2+ leukemic cells from BM of moribund mice with advanced leukemia. Cells were cytospun onto glass slides and Wright-Giemsa stained. The frequencies were calculated by counting 500 cells 3 times and the average values are depicted.

Because Ezh2Δ/Δ cells showed significant retardation in cell-cycle entry in vitro, we examined the expression of p16Ink4a and p19Arf, known major targets of PcG complexes. We purified the Mac-1+IL-7Rα−Lin−Sca-1−c-Kit+FcγRII/IIIhi fraction, which is enriched in LICs, from primary and secondary leukemic cells. p19Arf was highly de-repressed in Ezh2Δ/Δ serially replated cells, but expressed at very low levels in the LIC-enriched fraction of both primary and secondary leukemias. In contrast, p16Ink4a was barely detectable in either cultured cells or transplanted leukemias (supplemental Figure 4A).

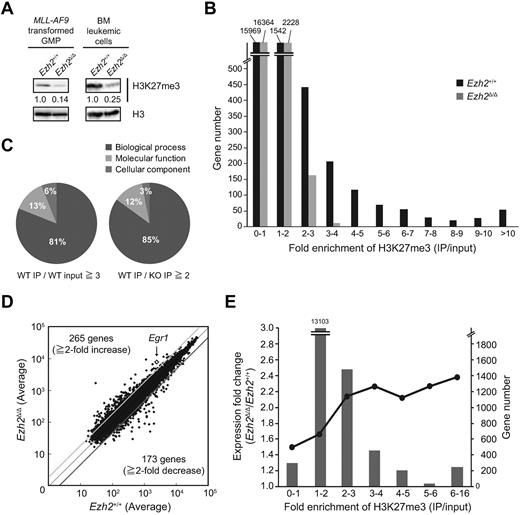

Ezh2 regulates genes relevant to the developmental and differentiation processes

To elucidate the mechanism of how Ezh2 regulates the progression of MLL-AF9–induced AML, we examined the genome-wide distribution of H3K27me3 by ChIP-seq analysis. First, Western blot analysis revealed a marked decrease in the levels of H3K27me3 in Ezh2Δ/Δ transformed GMPs in culture and in Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemic cells in vivo (Figure 5A). We next examined the presence of H3K27me3 marks in leukemia cells purified from the BM by ChIP-seq analysis. We focused on the region from 5.0 kb upstream to 3.0 kb downstream of transcription start sites (TSSs) of reference sequence (RefSeq) genes (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/RefSeq/)29 because H3K27me3 marks are usually enriched near TSSs or across the body of genes. ChIP-seq analysis identified 2563 genes with an H3K27me3 enrichment greater than 2-fold more than the levels of input in control AML cells. As expected, the deletion of Ezh2 caused a drastic reduction in these H3K27me3 marks (Figure 5B). Nonetheless, considerable levels of H3K27me3 remained even in the absence of Ezh2, suggesting that Ezh1 can at least partially complement Ezh2 in AML as it does in normal BM HSCs.7 To understand this mechanism, we analyzed the expression of Ezh1 and Ezh2 in HSCs and LICs, but detected no evidence for differential or compensatory expression of Ezh1 in LICs versus HSCs after Ezh2 deletion (supplemental Figure 4B).

Ezh2 regulates genes relevant to the development and differentiation processes. (A) Levels of H3K27me3 in MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs and BM leukemic cells. Histones were extracted from Ezh2+/+ or Ezh2Δ/Δ–transformed GMPs or CD45.2+ leukemic cells isolated from primary recipient mice and analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-H3K27me3 Ab. Levels of H3K27me3 were normalized to the amount of H3 and are indicated relative to Ezh2+/+ control values. The levels of H3K27me3 in Ezh2+/+ cells were arbitrarily set to 1. (B) Summary of H3K27me3 enrichment detected by ChIP-seq analysis. CD45.2+Ezh2+/+ and Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemic cells isolated from primary recipient mice were subjected to ChIP-seq analysis using an anti-H3K27me3 Ab. The fold enrichment values of H3K27me3 signals were calculated against the input signals (IP/input) from 5.0 kb upstream to 3.0 kb downstream of the TSS of RefSeq genes. (C) Pie graphs illustrating the proportion of categories of GO terms showing significant differences. GO analysis was performed using 1021 genes with the H3K27me3 enrichment (WT IP/WT input) greater than 3-fold in the control AML cells (left) and 584 genes that showed a reduction in H3K27me3 enrichment (WT IP/KO IP) more than 2-fold on deletion of Ezh2 (right). (D) A scatter diagram of microarray analysis. Lin−Sca-1−c-Kit+FcγRII/IIIhi BM leukemic cells were isolated from primary recipient mice and analyzed by microarray-based expression analysis. The average signal levels of Ezh2Δ/Δ cells compared with those of Ezh2+/+ cells are plotted. The light and dark gray lines represent the borderline for a 2-fold increase and a 2-fold decrease, respectively. Egr1 is indicated with a diamond. (E) Correlation of derepression in expression in Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemic cells in terms of the degree of H3K27me3 enrichment. The genes up-regulated on deletion of Ezh2 (Ezh2Δ/Δ/control leukemic cells > 1.0 in microarray analysis) were analyzed in terms of the degree of H3K27me3 enrichment in the control leukemic cells detected by ChIP-seq. The fold enrichment values for H3K27me3 were binned (each bin containing 1.0-fold enrichment). The number of genes in a bin and the average degree of up-regulation are indicated as bars and circles, respectively.

Ezh2 regulates genes relevant to the development and differentiation processes. (A) Levels of H3K27me3 in MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs and BM leukemic cells. Histones were extracted from Ezh2+/+ or Ezh2Δ/Δ–transformed GMPs or CD45.2+ leukemic cells isolated from primary recipient mice and analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-H3K27me3 Ab. Levels of H3K27me3 were normalized to the amount of H3 and are indicated relative to Ezh2+/+ control values. The levels of H3K27me3 in Ezh2+/+ cells were arbitrarily set to 1. (B) Summary of H3K27me3 enrichment detected by ChIP-seq analysis. CD45.2+Ezh2+/+ and Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemic cells isolated from primary recipient mice were subjected to ChIP-seq analysis using an anti-H3K27me3 Ab. The fold enrichment values of H3K27me3 signals were calculated against the input signals (IP/input) from 5.0 kb upstream to 3.0 kb downstream of the TSS of RefSeq genes. (C) Pie graphs illustrating the proportion of categories of GO terms showing significant differences. GO analysis was performed using 1021 genes with the H3K27me3 enrichment (WT IP/WT input) greater than 3-fold in the control AML cells (left) and 584 genes that showed a reduction in H3K27me3 enrichment (WT IP/KO IP) more than 2-fold on deletion of Ezh2 (right). (D) A scatter diagram of microarray analysis. Lin−Sca-1−c-Kit+FcγRII/IIIhi BM leukemic cells were isolated from primary recipient mice and analyzed by microarray-based expression analysis. The average signal levels of Ezh2Δ/Δ cells compared with those of Ezh2+/+ cells are plotted. The light and dark gray lines represent the borderline for a 2-fold increase and a 2-fold decrease, respectively. Egr1 is indicated with a diamond. (E) Correlation of derepression in expression in Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemic cells in terms of the degree of H3K27me3 enrichment. The genes up-regulated on deletion of Ezh2 (Ezh2Δ/Δ/control leukemic cells > 1.0 in microarray analysis) were analyzed in terms of the degree of H3K27me3 enrichment in the control leukemic cells detected by ChIP-seq. The fold enrichment values for H3K27me3 were binned (each bin containing 1.0-fold enrichment). The number of genes in a bin and the average degree of up-regulation are indicated as bars and circles, respectively.

To correlate the changes in H3K27me3 enrichment in the ChIP-seq analysis with overall biologic functions, we performed GO analysis on 1021 genes with H3K27me3 enrichment greater than 3-fold over the control AML cells and on 584 genes that showed a reduction in H3K27me3 enrichment of more than 2-fold on deletion of Ezh2. We found more than 80% of GO terms with significant differences (e-value < 0.05) were categorized into the biologic process (Figure 5C). Detailed analysis of GO annotations for biologic process identified a subset of genes related to differentiation, cell fate, development, apoptosis, and stem-cell function (supplemental Table 2). These data suggest that Ezh2 functions as a regulator of differentiation and stem-cell function in AML, as it does in pluripotent and somatic stem cells and other types of cancers.12-14,30,31

We next performed microarray analysis using Mac-1+IL-7Rα−Lin−Sca-1−c-Kit+FcγRII/IIIhi BM AML cells enriched in LICs.26 Even though the LIC frequency drops in the absence of Ezh2, this fraction was enriched in leukemic colony-forming cells in both Ezh2-deficient leukemias and control leukemias (supplemental Figure 4C). Microarray analysis revealed 265 genes that were either up-regulated by more than 2-fold or turned on and 173 genes that were either down-regulated more than 2-fold or turned off in Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemic cells compared with the control leukemic cells (Figure 5D and supplemental Table 3). We then analyzed the correlation of expression changes in Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemic cells in terms of the degree of H3K27me3 enrichment (Figure 5E). The degree of up-regulation after Ezh2 deletion in leukemic cells tended to be correlated positively with the degree of H3K27me3 enrichment at the up-regulated gene loci (Figure 5E). In contrast, genes down-regulated on deletion of Ezh2 were mostly devoid of H3K27me3 in the control AML cells and showed no correlation between down-regulation levels and degree of H3K27me3 enrichment (data not shown). The absence of Ezh2 did not affect the transcriptional activation of the major target genes of MLL-AF9, including HoxA9 and Meis1 (supplemental Figure 5A). Correspondingly, ChIP-seq analysis revealed very low enrichment of H3K27me3 on the genome covering these genes, whereas H3K27me3 was enriched on the gene body of Cdkn2a, one of the known major targets of PcG complexes, in the control but not Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemic cells (supplemental Figure 5B). The ChIP-seq profile of Zfp36l1, one of the derepressed genes in Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemic cells, also presented a clear reduction in levels of H3K27me3, particularly near the TSS (supplemental Figure 5B). These findings indicate that Ezh2 regulates genes relevant to differentiation, apoptosis, and stem cell function through modification of H3K27me3 in MLL-AF9–induced AML.

Overexpression of Egr1, one of the direct targets of Ezh2, promotes differentiation of AML

Because Ezh2 functions as transcriptional repressor, derepressed genes could be direct targets of Ezh2. Based on the ChIP-seq and microarray analysis data, many genes were potential candidates to be regulated directly by Ezh2 in AML. Egr1, one of the up-regulated genes in Ezh2-deficient cells, is a member of the immediate early response transcription factor family, which encode zinc-finger transcription factors and play a role in the development, cell growth, and response to stress in several cell types, including myeloid cells. It has been reported previously that EGR1 is a positive regulator of myeloid differentiation and suppresses leukemia by abrogating the E2F-1–mediated block in terminal myeloid differentiation.32-34 qRT-PCR in Mac1+IL-7Rα−Lin−Sca-1−c-Kit+FcγRII/IIIhi BM AML cells enriched in LICs showed that Egr1 was expressed more than 4-fold higher in Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemic cells compared with control AML cells (Figure 6A). ChIP-seq analysis showed that H3K27me3 was enriched over the Egr1 gene body in the control AML cells, but its level was reduced in Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemic cells (Figure 6B). This trend was confirmed by independent ChIP assays (Figure 6C-D). Interestingly, the reduction in the levels of H3K27me3 marks was relatively mild compared with the reduction in Ezh2 binding at both the Egr1 and the Cdkn2a (p16Ink4a and p19Arf) loci, suggesting a compensatory mechanism for H3K27me3 modification. (Figure 6D). We next overexpressed Egr1 in the control MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs and performed colony-forming assays. Overexpression of Egr1 attenuated replating efficiency significantly (Figure 6E) and resulted in the formation of more dispersed colonies and fewer compact colonies compared with control cells (Figure 6F). The Egr1-overexpressing colonies were primarily composed of differentiated myeloid cells, mostly macrophages and some granulocytes at various stages of differentiation. In contrast, the control colonies were composed predominantly of immature myeloblasts (Figure 6G). Transformed GMPs overexpressing Egr1 behaved in a manner similar to that of Ezh2Δ/Δ–transformed GMPs (Figure 6E-G). These results support ChIP-seq data in showing that Ezh2 represses directly the genes involved in myeloid differentiation, such as Egr1.

Overexpression of Egr1, one of the direct targets of Ezh2, promotes the differentiation of AML. (A) Expression of Egr1 in Lin−Sca-1−c-Kit+FcγRII/IIIhi BM leukemic cells isolated from primary recipient mice. mRNA levels of Egr1Z were evaluated by qRT-PCR and normalized to Hprt1 expression. Data are shown as the means ± SD for analyses from 3 different mice. (B) The H3K27me3 signal map at the Egr1 locus detected by the ChIP-seq analysis using an anti-H3K27me3 Ab. (C) Schematic diagram of the Egr1 and Ink4a/Arf loci indicating their genomic structures. Exons are demarcated by black boxes. Regions amplified from the precipitated DNA by site-specific quantitative PCR are indicated by arrows. (D) Q-ChIP analyses of CD45.2+ BM leukemic cells from recipient mice of primary transplantation. Black and gray bars represent Ezh2+/+ and Ezh2Δ/Δ cells, respectively. Abs specific to the H3K27me3 (top panel) or Ezh2 (bottom panel) were used. There were no detectable or very low levels of background signals with IgG isotype controls at all amplified regions. Percentages of input DNA are shown as the means ± SD for triplicate analyses. Data shown are representative of 2 independent experiments. **P < .01, *P < .05. (E) Colony-forming capacity of MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs overexpressing Egr1. MLL-AF9–transformed Cre-ERT;Ezh2+/+ GMPs were transduced with Egr1 or control retroviruses and purified by cell sorting using green fluorescent protein as a marker. Sorted cells (3000 cells each) were plated in methylcellulose medium containing 50 ng/mL of SCF, 10 ng/mL of FP6, 10 ng/mL of GM-CSF, and 10 ng/mL of IL-3. The black and gray bars represent compact and dispersed colonies, respectively. The data are shown as the means ± SD for triplicate analyses. **P < .01. (F) Morphology of colonies generated in panel E. Representative colonies observed under an inverted microscope. Magnification ×200. (G) Typical cell morphology of MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs overexpressing Egr1 after 3 days of culture in methylcellulose medium in panel E. Cells were cytospun onto glass slides and observed after Wright-Giemsa staining. Magnified images of the cells boxed are depicted in the insets. Magnification ×400 and ×1000 (insets).

Overexpression of Egr1, one of the direct targets of Ezh2, promotes the differentiation of AML. (A) Expression of Egr1 in Lin−Sca-1−c-Kit+FcγRII/IIIhi BM leukemic cells isolated from primary recipient mice. mRNA levels of Egr1Z were evaluated by qRT-PCR and normalized to Hprt1 expression. Data are shown as the means ± SD for analyses from 3 different mice. (B) The H3K27me3 signal map at the Egr1 locus detected by the ChIP-seq analysis using an anti-H3K27me3 Ab. (C) Schematic diagram of the Egr1 and Ink4a/Arf loci indicating their genomic structures. Exons are demarcated by black boxes. Regions amplified from the precipitated DNA by site-specific quantitative PCR are indicated by arrows. (D) Q-ChIP analyses of CD45.2+ BM leukemic cells from recipient mice of primary transplantation. Black and gray bars represent Ezh2+/+ and Ezh2Δ/Δ cells, respectively. Abs specific to the H3K27me3 (top panel) or Ezh2 (bottom panel) were used. There were no detectable or very low levels of background signals with IgG isotype controls at all amplified regions. Percentages of input DNA are shown as the means ± SD for triplicate analyses. Data shown are representative of 2 independent experiments. **P < .01, *P < .05. (E) Colony-forming capacity of MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs overexpressing Egr1. MLL-AF9–transformed Cre-ERT;Ezh2+/+ GMPs were transduced with Egr1 or control retroviruses and purified by cell sorting using green fluorescent protein as a marker. Sorted cells (3000 cells each) were plated in methylcellulose medium containing 50 ng/mL of SCF, 10 ng/mL of FP6, 10 ng/mL of GM-CSF, and 10 ng/mL of IL-3. The black and gray bars represent compact and dispersed colonies, respectively. The data are shown as the means ± SD for triplicate analyses. **P < .01. (F) Morphology of colonies generated in panel E. Representative colonies observed under an inverted microscope. Magnification ×200. (G) Typical cell morphology of MLL-AF9–transformed GMPs overexpressing Egr1 after 3 days of culture in methylcellulose medium in panel E. Cells were cytospun onto glass slides and observed after Wright-Giemsa staining. Magnified images of the cells boxed are depicted in the insets. Magnification ×400 and ×1000 (insets).

Discussion

Although the role of EZH2 in hematologic malignancies is controversial, it has been shown to function as both an oncogene and a tumor-suppressor gene, especially in myeloid malignancies. Although overexpression of Ezh2 is not sufficient to induce leukemia in mice,11 various lines of evidence suggest that EZH2 functions as an oncogene in AML. Overexpression of EZH2 has been reported in patients with high-risk MDS, MDS-derived AML, and AML, particularly in patients with complex karyotypes.15,35 The inhibitory effect of the knockdown of EZH2 and the similar effect of DZNep on AML cells further supports the oncogenic function of EZH2 in AML.21,22,36 In the present study, we have shown that deletion of Ezh2 compromises the progression of AML severely by promoting the differentiation of AML cells. AML was converted into CMML-like disease in the absence of Ezh2.

In the present study, we deleted Ezh2 after confirming the development of overt leukemia. Whereas deletion of Ezh2 retarded the increase in WBC counts moderately at 2 weeks after deletion, there was no difference in WBC counts at 4 weeks after deletion. In addition, although deletion of Ezh2 compromised cell-cycle progression significantly and caused increased apoptotic cell death, Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemic cells retained robust proliferative capacity. Therefore, once the leukemic state had been established, even the Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemias progressed similarly to the wild-type control leukemias. However, secondary transplantation clearly revealed compromised progression of Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemias accompanied by a reduction in LIC frequency. These findings suggest that Ezh2 depletion does not affect initiation of leukemia profoundly, but rather affects the maintenance of LICs or the protection against stresses imposed by serial transplantation. These findings support an oncogenic function of Ezh2 in AML and indicate that Ezh2 plays a critical role in the maintenance of leukemic stem cells by reinforcing their differentiation blockage. In contrast to our findings, it has been reported recently that deletion of Ezh2 induces γδ T-cell leukemia in mice, unveiling a tumor-suppressor function of EZH2.37 EZH2 appears to play distinctive roles depending on the disease type. Therefore, it will be important to assess the effects of deletion of Ezh2 on all murine models of myeloid malignancies. Furthermore, it should be noted that the function of Ezh2 is cell context dependent. It has been reported that when MLL-AF9 is expressed from its endogenous promoter, leukemia is not initiated efficiently from GMPs, but is initiated efficiently from HSCs.38 Therefore, the question arises whether the role of Ezh2 would be the same in MLL-AF9–induced disease initiated from HSCs.

PcG proteins are known as a multifaceted regulator of normal and cancer stem cells and are involved in the fine regulation of stem cell activities, including self-renewal and fate decision.30,31 Indeed, overexpression of Ezh2 prevents HSC exhaustion in serial transplantation.11 Ezh2 is not essential for BM HSCs because of functional redundancy with Ezh1.7,10 In the present study, we again observed that the deletion of Ezh2 caused a drastic reduction in the H3K27me3 marks, but considerable levels of H3K27me3 remained even in the absence of Ezh2 in leukemic cells. This observation indicates that Ezh1 can at least partially complement Ezh2 in AML, as it does in normal BM HSCs.7 Nevertheless, Ezh2-deficient leukemias had a lower frequency of LICs, were severely perturbed in progression, and were accompanied by prominent differentiation. Given that the loss of Ezh2 does not affect HSCs in terms of their frequency or self-renewal capacity or myeloid differentiation in mice,7 these findings suggest that the dependency on Ezh2 is higher in AML than it is in normal HSCs. Because of recent studies, novel therapeutic strategies against epigenetic abnormalities have gained in popularity. We reported previously that DZNep, but not 5-fluorouracil, reduced the number of tumor-initiating cells significantly in a mouse model of hepatocellular carcinoma.20 Together with AML's higher requirement for EZH2, it could be a potential target for epigenetic therapy aimed at the leukemic stem cells in AML.

According to previous studies, Ezh2 orchestrates the gene expression of developmental regulator genes and controls cell fate and differentiation of stem and progenitor cells.39,40 In the present study, our ChIP-seq analysis showed clearly that Ezh2 represses a cohort of genes relevant to differentiation and cell-fate decision. Combined derepression of several differentiation-related genes may account for the conversion of AML into CMML-like disease after deletion of Ezh2. CMML is a subtype of leukemia that is classified as MDS/MPN and is characterized by a tendency to differentiate and myeloid dysplasia. Deleting Ezh2 in AML recapitulated human CMML, and Ezh2Δ/Δ leukemias exhibited a tendency to exhibit myeloid dysplasia of both granulocytic and monocytic lineages. Nevertheless, our findings might represent an unusual outcome of perturbing AML and do not necessarily represent a good model of CMML.

As one of the direct targets of Ezh2 derepressed in Ezh2-deficient leukemia, we characterized the role of Egr1 in MLL-AF9–induced AML. Egr1 is a positive regulator of differentiation of myeloid cells, particularly the monocytic lineage,32-34 and is also known to be a tumor suppressor that transactivates tumor-suppressor genes, including TGFβ1, PTEN, and p53.41,42 Because EGR1 is located on chromosome 5q, EGR1 is proposed to be a candidate gene involved in the development of MDS/AML characterized by abnormalities of chromosome 5.43 In the present study, overexpression of Egr1 promoted differentiation and attenuated the growth of AML cells profoundly. These observations suggest that EGR1 is one of the direct targets of EZH2 in a leukemic setting and that it defines the leukemogenic capacity of LICs. Direct regulation of EGR1 by EZH2 has been reported previously in synovial sarcoma.44 However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of Egr1 being regulated by Ezh2 directly in hematopoiesis.

The Cdkn2a or Ink4a/Arf locus is an important target of PcG proteins. Bmi1, a key component of PRC1, is a potent negative regulator of the Ink4a/Arf locus. Bmi1-deficient HSCs are defective in self-renewal, but simultaneous deletion of Ink4a/Arf can restore their self-renewal capacity.4,5 We reported recently that Bmi1 is indispensable to the development of MLL-AF9–induced leukemia, and that deletion of both the Ink4a and Arf genes restores the leukemogenic capacity of Bmi1−/− LICs partially.24 In Ezh2-deficient leukemias, Ink4a was expressed partially and Arf was only derepressed moderately in LIC-enriched populations in vivo. However, in vitro, Ink4a was still only expressed scarcely, but the derepression of Arf was very drastic. These results suggest that Ezh1 can complement Ezh2 considerably in transcriptional repression of the Ink4a/Arf locus in vivo but not in culture, where cells are exposed to strong oxidative stresses that eventually cause derepression of Ink4a and Arf. Therefore, the contribution of derepressed Ink4a and Arf to the compromised progression of Ezh2-deficient leukemias in vivo is likely minimal. This could also be applicable to MDS, MPN, and MDS/MPN with loss-of-function mutations of EZH2. The degrees of derepression of the targets of EZH2 are cell type and context dependent.

As we reported previously in Bmi1,24 the absence of Ezh2 had little effect on the transactivation of targets of MLL-AF9 in the present study. These findings suggest that Ezh2 and Bmi1 are not involved in the transcriptional regulation of MLL-AF9 targets. However, our previous and present data show clearly that Ezh2 and Bmi1 are essential for LICs to acquire full leukemogenic activity. It is possible that the transcriptional circuit initiated by the MLL-AF9 fusion protein eventually involve these PcG proteins, possibly in the inhibition of differentiation programs in LICs. How the leukemic genes regulate PcG function in LICs will be a very interesting issue to pursue to further understand the role of PcG proteins in leukemia.

Note added in proof: While this work was in revision, a study describing the role of Ezh2 in MLL-AF9 leukemia was published (Neff et al45 ).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Shigeru Taketani for the Egr1 cDNA, Kristian Helin for an anti-Ezh2 antibody (AC22), Terumi Horiuchi for data mining of the ChIP-seq analysis, George Wendt for critical reading of the manuscript, and Mieko Tanemura for laboratory assistance.

This work was supported in part by grants-in-aid for scientific research (21390289 and 221S0002); Scientific Research on Innovative Areas, Genome Science (221S0002); the Global COE Program (Global Center for Education and Research in Immune System Regulation and Treatment) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan; a grant-in-aid for Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (CREST) from the Japan Science and Technology Corporation (JST); and grants from the Takeda Science Foundation, the Astellas Foundation for Research on Metabolic Disorders, and the Tokyo Biochemical Research Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: S.T. performed the experiments, analyzed the results, made the figures, and wrote the manuscript; S.M., G.S., T.C., J.Y., and M.M.-K. assisted with the experiments, including the hematopoietic analyses and microarray and ChIP analyses; Y.S. and S.S. assisted with the ChIP-seq analysis; C.N. and K.Y. provided critical advice on the project; H.K. provided conditional Ezh2-knockout mice; and A.I. conceived and directed the project, secured the funding, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Atsushi Iwama, MD, 1-8-1 Inohana, Chuo-ku, Chiba, 260-8670 Japan; e-mail: aiwama@faculty.chiba-u.jp.