Key Points

Loss of the oxygen sensor PHD2 in the HSC compartment in mice results in the HIF1α-driven induction of multipotent progenitors.

PHD2-deficient hematopoietic progenitors are outcompeted during severe stress while HSCs are encouraged to self-renew.

Abstract

Hypoxia is a prominent feature in the maintenance of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) quiescence and multipotency. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins (PHDs) serve as oxygen sensors and may therefore regulate this system. Here, we describe a mouse line with conditional loss of HIF prolyl hydroxylase 2 (PHD2) in very early hematopoietic precursors that results in self-renewal of multipotent progenitors under steady-state conditions in a HIF1α- and SMAD7-dependent manner. Competitive bone marrow (BM) transplantations show decreased peripheral and central chimerism of PHD2-deficient cells but not of the most primitive progenitors. Conversely, in whole BM transfer, PHD2-deficient HSCs replenish the entire hematopoietic system and display an enhanced self-renewal capacity reliant on HIF1α. Taken together, our results demonstrate that loss of PHD2 controls the maintenance of the HSC compartment under physiological conditions and causes the outcompetition of PHD2-deficient hematopoietic cells by their wild-type counterparts during stress while promoting the self-renewal of very early hematopoietic progenitors.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are responsible for the continuous production of all blood cell lineages throughout the life of an organism. The maintenance of their multipotency and self-renewal capacity is therefore of utmost importance. HSCs reside in specific “niches” in the bone marrow (BM) that provide a particular microenvironment to preserve their quiescence and reconstitution potential.1-3 The niche exposes the HSCs to several cues such as transforming growth factor β (TGFβ),4 CXCL12,5 angiopoietin-1,6 and most importantly regional hypoxia.2 Hypoxic maintenance of HSCs stabilizes the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIFα) proteins, which in turn play a vital role in preserving their functionality.7,8

The activity of the ubiquitously expressed HIF1α protein is primarily regulated by the oxygen-dependent HIF prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins (PHD1-3). These enzymes hydroxylate distinct proline sites on HIFα, followed by ubiquitination by an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex containing the von Hippel–Lindau protein (pVHL) and proteasomal degradation.9 PHD2 is thought to be the most important oxygen sensor during normoxia and mild hypoxia,10 which is highlighted by the fact that only PHD2 null mice die during development.11,12 Moreover, even PHD2-haplodeficient mice display different phenotypes including normalization of the endothelial lining, enhanced perfusion,13 and arteriogenesis dependent on the differentiation state of macrophages.14

Recently, it was shown that lack of HIF1α in the HSCs results in loss of quiescence accompanied by increased peripheral chimerism and subsequent exhaustion in serial BM transfers, although steady state hematopoiesis was not altered vastly.15 Conversely, overstabilization of HIF1α resulting from conditional abrogation of the VHL gene showed impaired reconstitution potential but enhanced self-renewal ability of HSCs.15

Although the role of HIF1α in HSCs has been studied to a greater extent, the role of the PHDs remains unexplored. In the present study, we use a recently reported mouse line in which PHD2 is conditionally ablated in the entire hematopoietic system, including the HSC compartment.16 Under physiological conditions, this leads to increased SMAD7-related proliferation of multipotent progenitors (MPP) in a HIF1α-dependent manner. Moreover, during severe stress, loss of PHD2 leads to self-renewal of HSCs and early MPPs.

Methods

Mice

A detailed description of the construction of the PHD2 floxed mouse line can be found in the supplemental information (supplemental Figure 1). The CD68:cre mouse line and detailed characterization of the CD68:cre-PHD2f/f (cKO) line were shown in a recent report from our research group.16 All mice used in this report were born in a normal Mendelian manner. Mouse strains were backcrossed to C57BL/6 at least 9 times. Mice were genotyped using primers described in supplemental Table 1. Penetrance in cKO and CD68:cre-PHD2/HIF1αff/ff (cDKO) mice was defined via quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) on BM, spleen, and Lineage− Sca1+ c-Kit+ (LSK) cells and genomic PCR on ear biopsies. Knockdown efficiencies for HIF1α in these genotypes were comparable to expression levels for PHD2 as demonstrated.

Mice were housed at the Experimental Centre at the University of Technology Dresden (Medical Faculty, University Hospital Carl-Gustav Carus) under specific pathogen-free conditions. Experiments were performed with male and female mice at the age of 8 to 10 weeks or as stated in the text. All animal experiments were in accordance with the facility guidelines on animal welfare and were approved by the Landesdirektion Dresden, Germany.

FACS

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis was performed on LSRII (Becton Dickinson), and sorting was done on Aria II (Becton Dickinson). Cell numbers were counted on MACS quant. Data were analyzed with DIVA (Becton Dickinson), MACS quantify (Miltenyi), or FlowJo (Tree Star) software. BM cells and fetal liver tissues were passed through 23G needles to get single-cell suspensions. Two femurs per mouse were used for HSC analysis, and 2 femurs and 2 tibiae per mouse were used for sorting.

For surface staining, BM cells were incubated with c-kit (A780, 2B8; eBioscience), Sca1 (PE-Cy5 or PE-Cy7 or PE-Cy5.5, D7; eBioscience), CD34 (FITC, RAM34; eBioscience), CD135 (PE or PE-Cy5, A2F10; eBioscience), CD48 (APC, HM48-1; eBioscience), and CD150 (PE-Cy7, TC15-12F12.2; BioLegend) for 55 minutes. Lineage-positive cells were excluded using a cocktail of biotinylated antibodies and staining with streptavidin (SA; eF450; eBioscience). The lineage cocktail included CD3 (145-2C11; eBioscience), CD19 (eBio1D3; eBioscience), NK1.1 (PK136; eBioscience), Ter119 (Terr119; eBioscience), CD11b (M1/70; eBioscience), Gr1 (RB6-8C5; eBioscience), and B220 (RA3-6B2; eBioscience). A total of 3 × 10^6 cells per mouse were acquired. For fetal liver cell staining, the same mixture was used but without the CD11b in the lineage cocktail.

Cell cycle analysis

Lineage depletion was done prior to surface staining using lineage antibody cocktail and SA magnetic beads (Dynabeads biotin binder; Invitrogen). For intracellular staining, the cells were fixed and permeabilized using fixation and permeabilization buffers from eBioscience. For distinction between the G0 and G1 phase, cells were stained for intracellular Ki-67 (PE, B56; BD Biosciences). DAPI (4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole; Molecular Probes) was used to measure the DNA content and separate the cells in S/G2/M phase from the G0 and G1 cells.

Apoptosis measurement

Lineage depletion was done prior to staining using lineage antibody cocktail and SA magnetic beads (Dynabeads biotin binder; Invitrogen). Staining for cKit (A780, 2B8; eBioscience) and Sca1 (PE-Cy5 or PE-Cy7 or PE-Cy5.5, D7; eBioscience) was done prior to staining with annexin V (BD Pharmingen) and phosphatidylinositol (BD Pharmingen). Cells were finally resuspended in annexin binding buffer (BD Pharmingen). Data were acquired on LSR II (Becton Dickinson).

Expression analysis

RNA was isolated using NucleoSpin RNA XS (Machery-Nagel). Complementary DNA was synthesized using random primers (Roche) and SuperScript II (Invitrogen). Expression levels were determined by performing quantitative real-time PCR using the Maxima SYBR Green QPCR Master Mix (Fermentas) on an iCycler iQ (Bio-Rad). Expression levels were normalized with the ΔΔCt method using primers given in supplemental Tables 2 and 3.

BM transfers, migration, and stress models

A total of 1 × 10^6 cKO or wild-type (WT) BM mononuclear cells (MNCs) from C57BL/6 (CD45.2) mice were transplanted into lethally irradiated (7.5 Gy) congenic SJL (CD45.1) mice. All mice were kept on water containing antibiotics for 2 weeks after irradiation. Mice were bled retro-orbitally every month to check for peripheral chimerism after 2 months and their BM was analyzed 4 months after transplantation.

For BM competition experiments, 2000 LSK cells from WT or cKO mice (CD45.2) were transplanted to lethally irradiated congenic recipients (CD45.1) along with 2 × 10^5 CD45.1 BM MNCs. Recipients were bled every month to check the peripheral chimerism and were sacrificed 4 months after transplantation for BM chimerism analysis.

For migration analysis, 5 × 10^5 Lin− cells were labeled with carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) and were injected into lethally irradiated recipients. BM was analyzed 20 hours after injection.

Statistical analysis

Data and graphs represent mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of representative experiments. Graph Pad Prism 5.04 was used to calculate statistical significance with 2-tailed unpaired t test.

Results

Generation of hematopoietic conditional PHD2 deficient mice

In order to study the role of the most prominent oxygen sensor in vivo, we generated PHD2f/f mice by gene targeting. To this end, we made a construct in which exons 2 and 3 were flanked by loxP sites (supplemental Figure 1A-D). Excision of PHD2 in virtually every cell in the body (Pgk:cre-PHD2f/f) led to ubiquitous HIF1α stabilization and consequent induction of Glut1 (supplemental Figure 1E). Consistent with other reports,11-13 PHD2−/− embryos died at midgestation (embryonic day [E] 13.5-14.5) due to malformation of the heart (supplemental Figure 1F).

To conditionally ablate PHD2 in the hematopoietic system, we combined the PHD2 floxed line with the recently described CD68:cre line to obtain cKO mice.16 Next to a subset of epithelial cells and erythropoietin-producing cells in kidney and brain, PHD2 is also significantly reduced in the entire BM in this cKO strain. However, no significant decrease of PHD2 was seen in endothelial cells, fibroblasts, or lysates of several nonhematopoietic organs.16 To understand at what level in the hematopoietic tree the deficiency of PHD2 is induced, we isolated the very early hematopoietic progenitor cells defined as Lineage− Sca1+ c-Kit+ and found that PHD2 is already significantly reduced in these cells to a similar extent as described for the other targeted cell types (Figure 1A).16 This strongly suggests that the entire hematopoietic system is potentially targeted, as was suggested by the data obtained from BM.

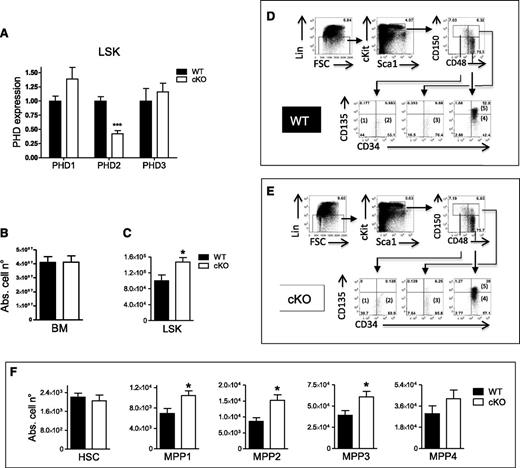

Loss of PHD2 in LSK cells leads to MPP self-renewal under steady-state conditions. (A) LSK cells were isolated from WT and CD68:cre-PHD2f/f (cKO) mice and tested for the presence of PHD1, PHD2, and PHD3 mRNA (n = 4-7). (B-C) Absolute cell number of (B) total BM and (C) LSK cells in the BM of WT and cKO littermates (n = 6). (D-E) Using 7-color flow cytometry, LSK BM can be subdivided into 5 populations based on differential expression of CD34, CD150, CD48, and CD135. The CD150+48−135− subset can be divided into (1) CD34− (HSC) and (2) CD34+ (MPP1) subsets. The CD150+48+ subset is almost exclusively (3) CD34+CD135− (MPP2), and the CD150−CD48+ subset can be divided into (4) CD135− (MPP3) and (5) CD135+ (MPP4) subsets. Percentages on FACS histograms are from a typical WT and cKO mouse. (F) The absolute numbers of the 5 LSK subsets (HSC/MPPs) in the BM of WT mice and their cKO littermates (n = 6). All data are mean ± SEM. *P < .05; ***P < .005. Abs. cell n°, absolute cell number.

Loss of PHD2 in LSK cells leads to MPP self-renewal under steady-state conditions. (A) LSK cells were isolated from WT and CD68:cre-PHD2f/f (cKO) mice and tested for the presence of PHD1, PHD2, and PHD3 mRNA (n = 4-7). (B-C) Absolute cell number of (B) total BM and (C) LSK cells in the BM of WT and cKO littermates (n = 6). (D-E) Using 7-color flow cytometry, LSK BM can be subdivided into 5 populations based on differential expression of CD34, CD150, CD48, and CD135. The CD150+48−135− subset can be divided into (1) CD34− (HSC) and (2) CD34+ (MPP1) subsets. The CD150+48+ subset is almost exclusively (3) CD34+CD135− (MPP2), and the CD150−CD48+ subset can be divided into (4) CD135− (MPP3) and (5) CD135+ (MPP4) subsets. Percentages on FACS histograms are from a typical WT and cKO mouse. (F) The absolute numbers of the 5 LSK subsets (HSC/MPPs) in the BM of WT mice and their cKO littermates (n = 6). All data are mean ± SEM. *P < .05; ***P < .005. Abs. cell n°, absolute cell number.

Loss of PHD2 enhances proliferation of MPPs under steady state in a HIF1α-dependent manner

To study whether loss of PHD2 in the hematopoietic system can affect the HSC compartment, we analyzed the LSK cells in the BM of WT and cKO mice. Although both genotypes had a similar absolute number of total BM MNCs (Figure 1B), cKO mice contained almost 50% more LSK cells than their WT littermates (Figure 1C). Furthermore, we subcategorized the LSK compartment on the basis of the expression of CD150, CD48, CD34, and CD135 (Flk2) into 5 subsets as described by Wilson and colleagues17 : a most primitive HSC subset (CD34− CD150+ CD48− CD135− LSK) and the increasingly differentiated MPP1 subset (CD34+ CD150+ CD48− CD135− LSK), MPP2 subset (CD34+ CD150+ CD48+ CD135− LSK), MPP3 subset (CD34+ CD150− CD48+ CD135− LSK), and MPP4 subset (CD34+ CD150− CD48+ CD135+ LSK) (Figure 1D-E). Using this developmental scheme, we found that the absolute numbers of MPP1, MPP2, and MPP3 were significantly increased in cKO mice (Figure 1F). In contrast, downstream of the LSKs, we found no difference in common myeloid progenitors or common lymphoid progenitors between both genotypes (supplemental Figure 2).

Takeda and colleagues have shown a nearly significant induction of LSK cells in an inducible somatic PHD2-deficient mouse line, suggesting that knocking out PHD2 after birth is sufficient to obtain more progenitor cells.18 We now also tested these hematopoietic progenitors in cKO and WT embryos. Although we found no difference in PHD2 messenger RNA (mRNA) or LSK cells in the fetal liver of E14.5 embryos (data not shown), we show that E17.5 cKO embryos contain a higher percentage of LSK cells and a significant lower amount of PHD2 (supplemental Figure 3A-B). In addition, we also tested PHD2+/− mice since they display significant changes in other models.13,14 However, no difference in LSK or any of the subsets could be detected in comparison with their WT littermates (supplemental Figure 4).

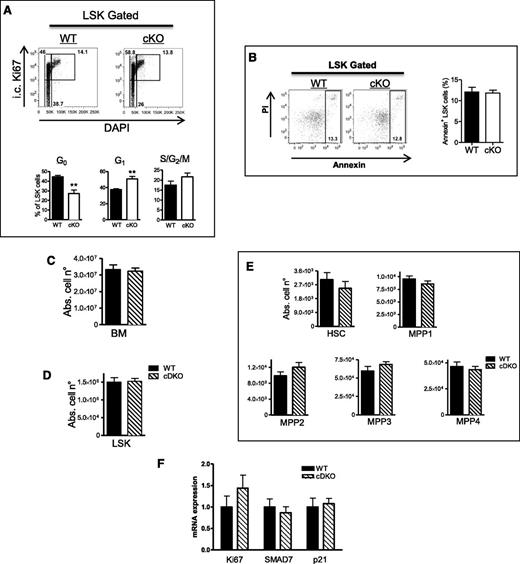

Next, we performed cell-cycle analysis (Ki67/DAPI) to evaluate whether the larger LSK pool in adult mice was associated with higher proliferation. Indeed, as compared with WT, significantly less cKO LSK cells were in the resting G0 phase. Consequently, more of them were actively cycling (especially in the G1 phase), although the difference in the S/G2/M phases was not significantly different (Figure 2A). Furthermore, we tested for apoptosis of the LSK cells but found no difference between the 2 genotypes (Figure 2B), strongly suggesting that only the higher proliferative potential of PHD2-deficient LSK cells leads to an increase in absolute cell number. In addition, we evaluated the expression profile of several genes in order to find a genetic link with the observed differences. Interestingly, our analyses showed a significant induction of the TGFβ inhibitor SMAD7 (Table 1). Consistent with this and as demonstrated previously in HSCs overexpressing SMAD7,19 the cell-cycle inhibitor p21Cip1/WAF1 (CDKN1A) was reduced in the cKO cells. We also tested several other potential candidates that have been described in relation to quiescence, cell division, and senescence of HSCs/MPPs before,15,20-23 but found no significant difference between both genotypes (Table 1).

Stabilization of HIF1α induces proliferation of PHD2-deficient LSK cells. (A) Cell-cycle analysis of LSK cells from WT and cKO BM. The lower gate (Ki67−ve) contains cells in the G0 phase of the cell cycle, the top left represents cells in the G1 phase, and the top right represents cells in S/G2/M phases. cKO mice show less quiescent (G0) LSK cells under steady-state conditions compared with their WT littermates (n = 4). (B) Annexin+ apoptotic cells in WT and cKO LSK cells. (C-E) The absolute numbers of (C) BM and (D) LSK cells in WT mice and their cDKO (CD68:cre-PHD2/HIF1αff/ff) littermates, (E) subsequently subdivided in the 5 HSC/MPP subsets. No difference was detected in BM, LSK, or any of the subsets (n = 7-8). (F) Expression profile (qRT-PCR) of different genes in LSK cells of WT and cDKO mice (n = 3-4). All data are mean ± SEM. **P < .01. Abs. cell n°, absolute cell number; i.c., intracellular.

Stabilization of HIF1α induces proliferation of PHD2-deficient LSK cells. (A) Cell-cycle analysis of LSK cells from WT and cKO BM. The lower gate (Ki67−ve) contains cells in the G0 phase of the cell cycle, the top left represents cells in the G1 phase, and the top right represents cells in S/G2/M phases. cKO mice show less quiescent (G0) LSK cells under steady-state conditions compared with their WT littermates (n = 4). (B) Annexin+ apoptotic cells in WT and cKO LSK cells. (C-E) The absolute numbers of (C) BM and (D) LSK cells in WT mice and their cDKO (CD68:cre-PHD2/HIF1αff/ff) littermates, (E) subsequently subdivided in the 5 HSC/MPP subsets. No difference was detected in BM, LSK, or any of the subsets (n = 7-8). (F) Expression profile (qRT-PCR) of different genes in LSK cells of WT and cDKO mice (n = 3-4). All data are mean ± SEM. **P < .01. Abs. cell n°, absolute cell number; i.c., intracellular.

Quantitative PCR on mRNA from sorted LSK cells (cKO vs WT) under steady-state conditions

| Gene . | cKO vs WT (Δ% ± SEM%) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| Ki67 | 29.3% ± 0.3% | .02 |

| Hes1 | 2.5% ± 9.5% | N.S. |

| VEGFA | 0.3% ± 11.1% | N.S. |

| TGFβ1 | −0.5% ± 2.8% | N.S. |

| TGFβR1 | −8.5% ± 2.7% | N.S. |

| TGFβR2 | 9.6% ± 7.0% | N.S. |

| SMAD7 | 65.6% ± 22.9% | .02 |

| c-myc | −3.3% ± 2.7% | N.S. |

| p16 | 1.2% ± 9.4% | N.S. |

| p21 | −22.3% ± 7.2% | .04 |

| p27 | 7.8% ± 8.7% | N.S. |

| p57 | 0.6% ± 2.8% | N.S. |

| ckit | −5.5% ± 2.3% | N.S. |

| Cited-2 | 29.0% ± 23.0% | N.S. |

| Gene . | cKO vs WT (Δ% ± SEM%) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| Ki67 | 29.3% ± 0.3% | .02 |

| Hes1 | 2.5% ± 9.5% | N.S. |

| VEGFA | 0.3% ± 11.1% | N.S. |

| TGFβ1 | −0.5% ± 2.8% | N.S. |

| TGFβR1 | −8.5% ± 2.7% | N.S. |

| TGFβR2 | 9.6% ± 7.0% | N.S. |

| SMAD7 | 65.6% ± 22.9% | .02 |

| c-myc | −3.3% ± 2.7% | N.S. |

| p16 | 1.2% ± 9.4% | N.S. |

| p21 | −22.3% ± 7.2% | .04 |

| p27 | 7.8% ± 8.7% | N.S. |

| p57 | 0.6% ± 2.8% | N.S. |

| ckit | −5.5% ± 2.3% | N.S. |

| Cited-2 | 29.0% ± 23.0% | N.S. |

N.S., nonsignificant.

Since PHD2 is the major regulator of HIF1α, we generated mice double deficient for PHD2 and HIF1α24 (CD68:cre-PHD2/HIF1αff/ff) and studied the HSC compartment in their BM. Intriguingly, alterations in the LSK and MPP populations as seen in cKO mice were completely abolished (Figure 2C-E), strongly suggesting that the HSC phenotype in PHD2-deficient mice under steady-state conditions is a HIF1α-dependent event. Moreover, the Ki67, SMAD7, as well as p21Cip1/WAF1 mRNA content in cDKO and WT LSK cells was not different, which is also in line with an earlier study showing that SMAD7 can be activated by hypoxia in a HIF1α/pVHL-dependent manner (Figure 2F).25 Taken together, our data show that loss of PHD2 in the HSC compartment leads to enhanced HIF1α-related proliferation of early MPP fractions, which might be directly related to a reduced activity of the TGFβ pathway.

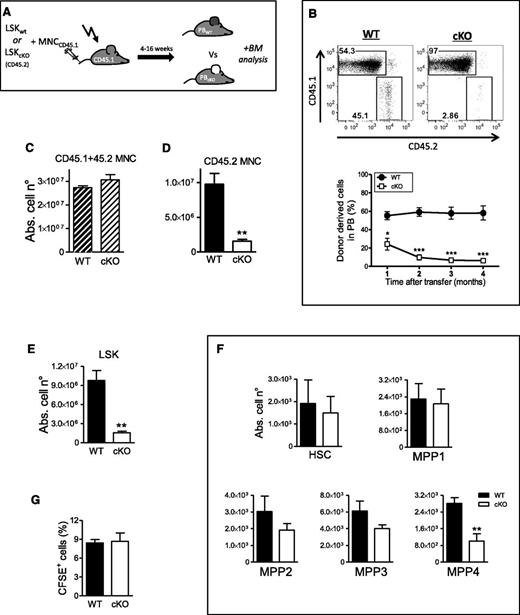

PHD2-deficient hematopoietic progenitors are outcompeted by their WT counterparts

Under conditions of extreme stress such as BM transplantation, quiescent HSCs exit dormancy to proliferate and self-renew.26 To investigate the role of PHD2 in this setting, we transplanted 2000 fluorescence-activated cell sorted LSK cells from cKO or WT mice (CD45.2) into lethally irradiated CD45.1 congenic recipients together with CD45.1 competitor cells (Figure 3A). Already 4 weeks after transplantation, cKO donor cells reached lower peripheral blood (PB) chimerism than WT cells, which progressed to a highly significant difference thereafter (Figure 3B). Interestingly, the total amount of BM cells (CD45.1 + 45.2 MNC) showed no difference 16 weeks after transplantation (Figure 3C). However, this was only because primarily competitor cells (CD45.1 MNC) replenished the BM when coinjected with PHD2-deficient LSK cells. Indeed, Figure 3D shows more than 80% reduction in CD45.2 cKO MNCs in the BM compared with WT mice. In addition, the total amount of cKO LSK cells was also dramatically reduced in comparison with the WT LSK cells in the control group (Figure 3E). Remarkably, this difference was almost exclusively related to the enormous reduction of the least primitive MPPs, mainly MPP4 (Figure 3F), whereas no changes could be detected in the HSC or MPP1 population. This suggests that the fitness of PHD2 mutant progenitors to compete with WT precursors is compromised to some extent, hence resulting in the decreased chimerism. Since impaired repopulation has been related to defective homing of transplanted VHL-deficient hematopoietic precursors,15 we also quantified CFSE-labeled WT or cKO Lin− cells injected into lethally irradiated recipients. However, our results show no difference in the percentage of retained cells (Figure 3G), strongly suggesting that the decreased chimerism is independent of the ability of PHD2-deficient precursors to home to the BM.

PHD2-deficient hematopoietic progenitors are outcompeted by WT littermate cells. (A) Schematic overview of the competitive BM transplantation model in lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipient mice. All mice were bled every 4 weeks and PB chimerism was measured via FACS. Final analysis on BM cells was performed 16 weeks after injection. (B) Representative FACS plots showing PB chimerism 16 weeks after transplantation. Graphical illustration at the indicated times after BM transfer representing the percentage of donor-derived CD45.2 cells (WT or cKO) (n = 5). (C-D) The absolute number of CD45.2 WT and cKO BM cells (C) with or (D) without CD45.1 WT competitor BM cells, 16 weeks after BM transfer (n = 5). (E-F) The absolute number of WT and cKO in the (E) LSK compartment and (F) subdivided in the 5 HSC/MPP (n = 5). (G) Homing of CFSE-labeled Lin− cells to BM from WT or cKO mice 20 hours after transfer (n = 5). Abs. cell n°, absolute cell number.

PHD2-deficient hematopoietic progenitors are outcompeted by WT littermate cells. (A) Schematic overview of the competitive BM transplantation model in lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipient mice. All mice were bled every 4 weeks and PB chimerism was measured via FACS. Final analysis on BM cells was performed 16 weeks after injection. (B) Representative FACS plots showing PB chimerism 16 weeks after transplantation. Graphical illustration at the indicated times after BM transfer representing the percentage of donor-derived CD45.2 cells (WT or cKO) (n = 5). (C-D) The absolute number of CD45.2 WT and cKO BM cells (C) with or (D) without CD45.1 WT competitor BM cells, 16 weeks after BM transfer (n = 5). (E-F) The absolute number of WT and cKO in the (E) LSK compartment and (F) subdivided in the 5 HSC/MPP (n = 5). (G) Homing of CFSE-labeled Lin− cells to BM from WT or cKO mice 20 hours after transfer (n = 5). Abs. cell n°, absolute cell number.

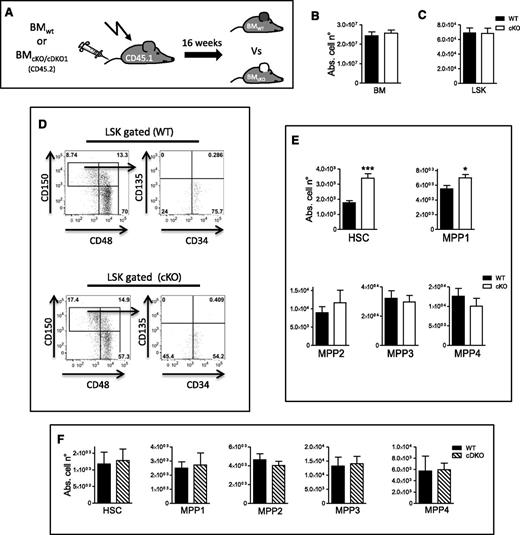

Whole BM transplantation induces self-renewal of PHD2-deficient HSCs

We next wanted to evaluate if early hematopoietic progenitors lacking PHD2 can completely repopulate the BM after irradiation. For this, we performed a whole-BM transfer model without competitor cells. CD45.2 BM MNCs from cKO or WT mice were transplanted into lethally irradiated CD45.1 mice and the BM stem cell compartment was analyzed 16 weeks later (Figure 4A). Strikingly, we observed no difference in the absolute number of BM or LSK cells between both genotypes (Figure 4B-C), strongly suggesting that under noncompetitive conditions, PHD2-deficient early hematopoietic progenitors can engraft, differentiate, and reconstitute the entire hematopoietic system in lethally irradiated recipients. In addition, we also found almost twice as many cKO CD34− HSCs and significantly more MPP1 cells compared with WT controls (Figure 4D-E). This underscores the enhanced self-renewal capacity of PHD2-deficient HSCs during stress.

HIF1α induces self-renewal of PHD2-deficient HSCs/MPP1 during transplantation stress. (A) Schematic overview of the whole-BM–transplantation mouse model in lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipient mice. Analysis was performed 16 weeks after intravenous injection of BM cells. (B-C) The absolute number of WT and cKO (B) total BM and (C) LSK cells in recipient mice. Representative FACS plots (D) from a WT or cKO BM recipient with the latter (E) showing significantly more cells in HSC/MPP1 compartment (n = 5). (F) The absolute number of WT and cDKO1 total BM LSK cells in recipient mice subsequently subdivided in the 5 HSC/MPP subsets showing no significant difference in any of the investigated compartments (n = 5-7). Abs. cell n°, absolute cell number.

HIF1α induces self-renewal of PHD2-deficient HSCs/MPP1 during transplantation stress. (A) Schematic overview of the whole-BM–transplantation mouse model in lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipient mice. Analysis was performed 16 weeks after intravenous injection of BM cells. (B-C) The absolute number of WT and cKO (B) total BM and (C) LSK cells in recipient mice. Representative FACS plots (D) from a WT or cKO BM recipient with the latter (E) showing significantly more cells in HSC/MPP1 compartment (n = 5). (F) The absolute number of WT and cDKO1 total BM LSK cells in recipient mice subsequently subdivided in the 5 HSC/MPP subsets showing no significant difference in any of the investigated compartments (n = 5-7). Abs. cell n°, absolute cell number.

Since it was shown in various stress settings that HIF1α is required to preserve HSC homeostasis,15 we performed the whole BM transplantation model with either cDKO1 or WT MNCs. Interestingly, 16 weeks after transplantation, we detected no substantial difference between both genotypes in any of the stem cell compartments (Figure 4F). Taken together, our data provide evidence that the self-renewal capacity of PHD2-deficient hematopoietic progenitors is mediated by HIF1α while their repopulation capacity is impaired in a competitive setting with WT cells.

Discussion

In the present study, we used a recently described conditional deficient mouse line to investigate the role of PHD2 in the HSC compartment. We have demonstrated that under steady-state conditions, loss of PHD2 leads to proliferation of very early hematopoietic progenitors, whereas during severe stress, PHD2-deficient CD34− HSCs display a clear preference for self-renewal.

Although CD68 has been described as a marker mainly limited to monocytes and macrophages,27,28 our cKO mouse line reveals at least temporary expression in several epithelial lineages16 but more importantly in LSK cells. The net result is a significant downregulation of PHD2 in the entire hematopoietic system. LSK cells are not just randomly distributed in the BM but arranged in a positional hierarchy depending on their maturation state. Moreover, the oxygen levels in these so-called niches play a critical role in regulating the self-renewal, quiescence, and differentiation of these cells (Figure 5).29-31 We here demonstrate for the first time that under steady-state conditions, conditional loss of the oxygen sensor PHD2 stimulates proliferation of the HSC compartment. This resulted in significantly higher amounts of the most primitive classes of MPPs, while the most quiescent CD34− HSCs remained unchanged. The latter is in line with the concept that in an unstimulated environment, HSCs are dormant and reside close to the endosteum in extremely hypoxic conditions,32 making the presence or absence of an oxygen-dependent enzyme like PHD2 virtually irrelevant. Additionally, we found no difference in the common myeloid and lymphoid progenitors downstream of the MPPs, suggesting that the latter cells accumulated due to enhanced self-renewal.

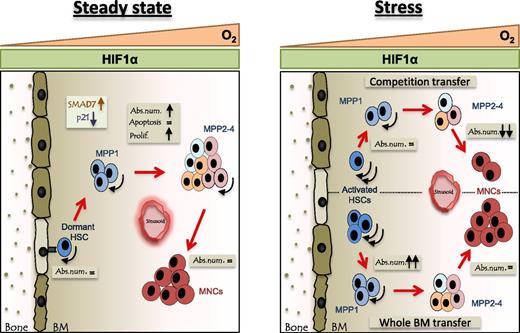

Schematic overview of the stem cell compartment in the bone of cKO mice during steady-state and severe stress. Oxygen levels decrease from sinusoids toward the endosteum (O2 triangle). In cKO mice, hematopoietic cells lack PHD2 and will, irrespective of the oxygen gradient, contain constant levels of HIF1α (HIF1α rectangle). Arc arrow indicates self-renewal capacity. Left: Under steady-state conditions, the absolute number of the PHD2-deficient MPPs is increased due to the sustained HIF1α activity and consequent inhibition of the TGFβ pathway. Right: Under severe stress, induced by irradiation and transplantation of BM or LSK cells, HSCs deficient for PHD2 exhibit enhanced self-renewal. However, PHD2-deficient precursors with a reduced self-renewal capacity (eg, MPP4) were outcompeted by the WT cells and therefore showed decreased chimerism. Abs. num., absolute number; Prolif., proliferation.

Schematic overview of the stem cell compartment in the bone of cKO mice during steady-state and severe stress. Oxygen levels decrease from sinusoids toward the endosteum (O2 triangle). In cKO mice, hematopoietic cells lack PHD2 and will, irrespective of the oxygen gradient, contain constant levels of HIF1α (HIF1α rectangle). Arc arrow indicates self-renewal capacity. Left: Under steady-state conditions, the absolute number of the PHD2-deficient MPPs is increased due to the sustained HIF1α activity and consequent inhibition of the TGFβ pathway. Right: Under severe stress, induced by irradiation and transplantation of BM or LSK cells, HSCs deficient for PHD2 exhibit enhanced self-renewal. However, PHD2-deficient precursors with a reduced self-renewal capacity (eg, MPP4) were outcompeted by the WT cells and therefore showed decreased chimerism. Abs. num., absolute number; Prolif., proliferation.

Furthermore, using an extensive set of genes related to quiescence, cell division, and senescence of early hematopoietic precursors,15,20-23 we sought to unravel the link between loss of PHD2 and induction of proliferation of LSK cells. Although most of the tested genes were equally expressed in cKO and WT LSK cells, we detected a significant induction of SMAD7, an intracellular inhibitor of the TGFβ pathway, as well as a modest but consistent downregulation of the TGFβ-regulated cell-cycle inhibitor p21.19,33 TGFβ is a very potent inhibitor of proliferation of hematopoietic progenitors.34-36 In addition, overexpression of SMAD7 has been shown to induce proliferation and self-renewal of the BM-LSK cells without any abnormalities in lineage distribution.19 Furthermore, SMAD7 can be regulated by hypoxia in a HIF1α/pVHL-dependent manner.25 Accordingly, mice double deficient for PHD2 and HIF1α show no difference in SMAD7 or p21 expression compared with their WT littermates. Thus, our data strongly suggest that under physiological conditions, loss of PHD2 in the HSC compartment results in increased cell-cycle activity via inhibition of the TGFβ pathway due to HIF1α stabilization.

Noteworthy, although cKO mice have a normal life span, they display a severe form of erythrocytosis induced by the overexpression of erythropoietin through HIF2α stabilization.16 However, the additional red blood cell production is almost exclusively controlled by the spleen, which is reflected by the fact that cKO mice show no difference in megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors and total cellularity in the BM as compared with WT littermates.16 Furthermore, cDKO mice show a very similar degree of erythrocytosis. Therefore, our results in the HSC compartment are most likely to be directly dependent on the loss of PHD2 in these very early hematopoietic progenitors.

In response to a severe stress situation like irradiation and subsequent BM transplantation, HSCs start to actively cycle in order to replenish the hematopoietic system.32 In a competitive repopulation model using either cKO or WT LSK cells combined with CD45.1 competitor MNCs, we found that the repopulation potential of cKO progenitors is greatly hampered. Indeed, 1 month after transplantation, PB chimerism in the cKO recipients was already significantly lower than in the WT and decreased further thereafter. In the BM, only about 20% of the entire LSK compartment consisted of cKO cells, whereas no difference was detected for the most immature fractions, HSCs and MPP1. This is in line with recent results obtained with mice conditionally deficient for another HIFα regulator, VHL.15 However, unlike the data obtained by Takubo and colleagues, PHD2-deficient hematopoietic precursors showed no impaired homing to the bone, suggesting a separate mechanism for decreased peripheral and central chimerism. Conversely, in a noncompetitive transplantation model, PHD2-deficient cells are able to replenish the entire BM, showing that cKO cells are indeed capable of differentiating normally into mature cells. Interestingly, we also found twice as many cKO HSCs and a significantly higher amount of MPP1 cells, as compared with WT, an effect that was completely abolished in cells lacking both PHD2 and HIF1α. Taken together, our data strongly suggest that during severe stress, loss of PHD2 is a crucial step in driving HSCs and early MPPs to self-renewal. Throughout competition, PHD2-deficient hematopoietic progenitor cells are outcompeted by the WT precursors. However, the fact that we found no difference in total cellularity of HSC and MPP1 is attributed to their increased self-renewal capacity during severe stress, which compensates for the lost cell numbers.

In conclusion, we have shown through loss-of-function mutations that under steady-state conditions, loss of PHD2 in early hematopoietic progenitor cells results in HIF1α-driven self-renewal of the MPPs and in severe stress of HSCs and MPP1 (Figure 5). This not only widens the concept of the role of oxygen in HSC functionality but also might have important implications for the treatment of hematologic malignancies.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the team of Dr Roland Jung for excellent technical support. The work was performed as a collaborative project within the COST Action TD0901 “HypoxiaNet”.

R.P.S., K.F, J.K, S.M., and A.M. were supported by the Emmy Noether program (the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft [DFG], Germany). B.W. is an Emmy Noether fellow. This work was supported by grants from the MeDDrive-Programm (TU Dresden, Germany) (B.W.), the DFG (WI 3291/1-1 and 1-2) (B.W.), and Miltenyi Biotec (Bergisch Gladbach, Germany).

Authorship

Contribution: R.P.S., K.F., J.K., S.M., and A.M. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and helped write the manuscript; A.G. designed and made the PHD2 targeting construct; T.G. provided helpful discussions and analyzed data; R.N. helped to make the PHD2 conditional mouse and provided helpful discussions; K.A. provided different constructs, supervised the embryonic stem cell work, and provided helpful discussions; A.F.S. designed and supervised the construction of the PHD2 targeting vector; C. Willam, G.B., and S.B. provided helpful tools; C. Waskow provided helpful tools and discussions; T.C. provided helpful tools and discussions and helped write the manuscript; and B.W. designed the study, supervised the overall project, performed experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for J.K. is Department of Nephrology and Hypertension, University Clinic Erlangen, Germany.

The current affiliation for S.M. is Institute of Pathology, Charite, Berlin, Germany.

The current affiliation for A.G. is Novartis, Basel, Switzerland.

Correspondence: Ben Wielockx, Emmy Noether Group (DFG), Institute of Pathology, University of Technology Dresden, Schubertstrasse 15, D-01307 Dresden, Germany; e-mail: ben.wielockx@uniklinikum-dresden.de.

References

Author notes

R.P.S., K.F., J.K., and S.M. contributed equally to this study.